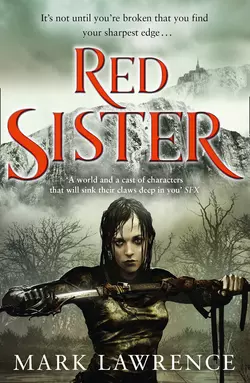

Red Sister

Mark Lawrence

It's not until you're broken that you find your sharpest edge"I was born for killing – the gods made me to ruin"At the Convent of Sweet Mercy young girls are raised to be killers. In a few the old bloods show, gifting talents rarely seen since the tribes beached their ships on Abeth. Sweet Mercy hones its novices’ skills to deadly effect: it takes ten years to educate a Red Sister in the ways of blade and fist.But even the mistresses of sword and shadow don’t truly understand what they have purchased when Nona Grey is brought to their halls as a bloodstained child of eight, falsely accused of murder: guilty of worse.

Copyright (#ulink_8c317c15-5a0b-580c-abca-fcaacc0bbd77)

HarperVoyager an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2017

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2017

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018 Cover images: © Tomasz Jedruszek (girl), Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com) (background images)

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008152291

Ebook Edition © April 2017 ISBN: 9780008152314

Version: 2018-10-26

Dedication (#ulink_ae3b37c4-c269-5eb7-969d-131834464d4a)

To Celyn, who needs no words for eloquence.

Contents

Cover (#u3653f8e0-e295-5f15-8597-522aeaea233e)

Title Page (#u5fea1ab3-a5c1-5916-879b-f5a997bd49e9)

Copyright (#u4bedbed4-10b5-500b-8929-026537996f21)

Dedication (#u817baff9-5b62-56a1-a524-3fcc3250d6b1)

Author’s Note (#u1e2d266a-1acf-5118-a1d5-730a0c365e32)

Red Class (#ua070c133-3933-5383-8b6c-50a47c12b44a)

Prologue (#u976551d5-87c7-56b4-853a-3e2f22dfc297)

Chapter 1 (#u92265d20-2ee0-5044-a6b4-c08f3c59d9c6)

Chapter 2 (#ud0712401-dd4c-54a0-8d97-1b7fe91520c2)

Chapter 3 (#uaf383bc6-2919-5fcb-a0d7-d31b250a5fae)

Chapter 4 (#u66419715-4320-528d-9536-a771147d9b1a)

Chapter 5 (#ue20f2eb1-31aa-5f0e-a7c0-0d9f1d680545)

Chapter 6 (#ucac84ec1-8538-52ed-a671-4ea295418b04)

Chapter 7 (#u718d4038-0c72-58ca-bea7-aea1c86cb8cc)

Chapter 8 (#u45841767-bb9e-50f4-9ec1-10a6d2e3c1bf)

Chapter 9 (#u1457845c-8171-529e-a28b-14de17b1bc36)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Grey Class (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mark Lawrence (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#ulink_e6e84eae-794c-52f0-bcf3-58d2ba66b15d)

Rather than place this background information in an appendix at the back where you might not notice it until you’ve finished the book (I’ve done that before) I’m putting it here at the front. However, it is best to skip it and return only if you find you need it. All the information here is given to you in the text and unfolds naturally with the story.

The people of Abeth descend from four ‘tribes’. These tribes were:

Gerant – distinguished by their great size

Hunska – distinguished by their speed. A dark-haired, dark-eyed people

Marjal – distinguished by their ability to tap into the lesser magics

Quantal – distinguished by their ability to walk the Path and work greater magics

The great families of empire adopt the suffix -sis when the head of the family is named a lord by the emperor. The emperor’s own family are the Lansis. Other families of note include the Tacsis, Jotsis, Memsis, Galamsis, Leensis, Gersis, Rolsis, and Chemsis.

In the Convent of Sweet Mercy novices move through four classes on their way to taking holy orders. A novice must graduate from each class. The classes are named after the four orders of nun:

Red Class – typical novice age 9-12

Grey Class – typical novice age 13-14

Mystic Class – typical novice age 15-16

Holy Class – typical novice age 17-19

On taking holy orders novices become nuns. They follow one of the following paths:

Bride of the Ancestor (Holy Sister) – a nun concerned with honouring the Ancestor and maintaining the faith. The most common calling

Martial Sister (Red Sister) – a nun skilled in armed and unarmed combat, usually showing hunska blood

Sister of Discretion (Grey Sister) – a nun skilled in espionage, stealth, and poisons. Often showing marjal blood and a talent for shadow-work

Mystic Sister (Holy Witch) – a nun able to walk the Path and manipulate threads. Always showing quantal blood

Dramatis Personae

Nuns (in order of superiority)

Glass: Abbess of Sweet Mercy Convent, also known as Shella Yammal

Rose: Sister Superior, Holy Sister, runs the sanatorium

Wheel: Sister Superior, Mistress Spirit, Holy Sister, teaches Spirit classes

Apple: Mistress Shade, Grey Sister, also known as the Poisoner, teaches Shade classes

Pan: Mistress Path, Holy Witch, teaches Path classes

Rule: Mistress Academia, Holy Sister, teaches Academia classes

Tallow: Mistress Blade, Red Sister, teaches Blade classes

Chrysanthemum: Holy Sister, mostly known as Sister Mop

Flint: Red Sister, Grey Class mistress

Kettle: Grey Sister

Oak: Holy Sister, Red Class mistress

Rock: Red Sister

Novices

Alata: junior novice

Arabella Jotsis: junior novice, quantal and hunska blood

Clera Ghomal: junior novice, Nona’s friend, hunska blood

Croy: junior novice

Darla: junior novice, gerant blood

Ghena: junior novice, hunska blood

Hessa: junior novice, Nona’s friend from Giljohn’s cage, quantal blood

Jula: junior novice, Nona’s friend, studious

Kariss: junior novice

Katcha: junior novice

Ketti: junior novice, hunska blood

Leeni: junior novice

Mally: junior novice, Grey Class head-girl

Ruli: Nona’s friend, marjal blood

Sarma: junior novice

Sharlot: junior novice

Sheelar: junior novice

Suleri: senior novice

Others

Emperor Crucical: his palace is in the city of Verity

Sherzal: the emperor’s sister. Her palace is close to the Scithrowl border

Velera: the emperor’s sister. Her palace is on the coast

High Priest Jacob: head of the Church of the Ancestor

Archon Nevis: high-ranking priest

Archon Anasta: high-ranking priestess

Archon Philo: high-ranking priest

Archon Kratton: high-ranking priest

Thuran Tacsis: lord, head of the Tacsis family

Raymel Tacsis: heir to Thuran Tacsis, Caltess ring-fighter, gerant blood

Lano Tacsis: Thuran Tacsis’s second son, hunska blood

Academic Rexxus Degon: senior Academy man

Markus: child from Giljohn’s cage, marjal blood

Saida: child from Giljohn’s cage, gerant blood

Willum: child from Giljohn’s cage, marjal blood

Chara: child from Giljohn’s cage, marjal blood

Partnis Reeve: owner of the Caltess fight-hall

Gretcha: Caltess ring-fighter, gerant blood

Maya: Caltess apprentice, gerant blood

Regol: Caltess trainee, hunska blood

Denam: Caltess trainee, gerant blood

Tarkax: known as ‘the Ice-Spear’, renowned warrior from the ice-tribes

Yisht: warrior from the ice tribes, serves Sherzal

Zole: girl from the ice tribes, Sherzal’s ward

Irvone Galamsis: high court judge

Sister Owl: legendary Red Sister (dead)

Sister Cloud: legendary Red Sister (dead)

Safira: former senior novice, works for Sherzal

Malkin: Abbess Glass’s cat

Argus: prison guard at Harriton

Dava: prison guard at Harriton

John Fallon: prison guard at Harriton

Herber: graveman

Jame Lender: prisoner executed at Harriton

Red Class (#ulink_78245627-6ea2-5456-96c9-d220622a3244)

Prologue (#ulink_238038e2-0b73-55bc-a2a6-dfee9e77c518)

It is important, when killing a nun, to ensure that you bring an army of sufficient size. For Sister Thorn of the Sweet Mercy Convent Lano Tacsis brought two hundred men.

From the front of the convent you can see both the northern ice and the southern, but the finer view is out across the plateau and over the narrow lands. On a clear day the coast may be glimpsed, the Sea of Marn a suggestion in blue.

At some point in an achingly long history a people, now lost to knowledge, had built one thousand and twenty-four pillars out on the plateau: Corinthian giants thicker than a thousand-year oak, taller than a long-pine. A forest of stone without order or pattern, covering the level ground from flank to flank so that no spot upon it lay more than twenty yards from a pillar. Sister Thorn waited amid this forest, alone and seeking her centre.

Lano’s men began to spread out between the columns. Thorn could neither see nor hear her foe approach, but she knew their disposition. She had watched earlier as they snaked up the west trail from Styx Valley, three and four abreast: Pelarthi mercenaries from the ice-margins, furs of the white bear and the snow-wolf over their leathers, some with scraps of chainmail about them, ancient and dark or bright as new, depending on their luck. Many carried spears, some swords; one man in five carried a short-bow of recurved horn. Tall men in the main, fair-haired, their beards short or plaited, the women with lines of blue paint across their cheeks and foreheads like the rays of a cold sun.

Here’s a moment.

All the world and more has rushed eternity’s length to reach this beat of your heart, screaming down the years. And if you let it, the universe, without drawing breath, will press itself through this fractured second and race to the next, on into a new eternity. Everything that is, the echoes of everything that ever was, the roots of all that will ever be, must pass through this moment that you own. Your only task is to give it pause – to make it notice.

Thorn stood without motion, for only when you are truly still can you be the centre. She stood without sound, for only silent can you listen. She stood without fear, for only the fearless can understand their peril.

Hers the stillness of the forest, rooted restlessness, oak-slow, pine-quick, a seething patience. Hers the stillness of ice walls that face the sea, clear and deep, blue secrets held cold against the truth of the world, a patience of aeons stacked against a sudden fall. Hers the stillness of a sorrow-born babe unmoving in its crib. And of the mother, frozen in her discovery, fleeting and forever.

Thorn held a silence that had grown old before first she saw the world’s light. A quietude passed down generations, the peace that bids us watch the dawn, an unspoken alliance with wave and flame that lets both take all speech from tongues and sets us standing before the water’s surge and swell, or waiting to bear witness to fire’s consuming dance of joy. Hers the silence of rejection, of a child’s hurt: mute, unknowing, a scar upon the years to come. Hers the unvoiced everything of first love, tongue-tied, ineloquent, the refusal to sully so sharp and golden a feeling with anything as blunt as words.

Thorn waited. Fearless as flowers, bright, fragile, open to the sky. Brave as only those who’ve already lost can be.

Voices reached her, the Pelarthi calling out to each other as they lost sight of their numbers in the broken spaces of the plateau. Cries rang across the level ground, echoing from the pillars, flashes of torchlight, a multitude of footfalls, growing closer. Thorn rolled her shoulders beneath black skin armour. She tightened the fingers of each hand around the sharp weight of a throwing star, her breathing calm, heart racing.

‘In this place the dead watch me,’ she breathed. A shout broke out close at hand, figures glimpsed between two pillars, flitting across the gap. Many figures. ‘I am a weapon in service to the Ark. Those who come against me will know despair.’ Her voice rose along with the tension that always presaged a fight, a buzzing tingle across her cheekbones, a tightness in her throat, a sense of being both deep within her own body, and above and around it at the same time.

The first of the Pelarthi jogged into view, and seeing her, stumbled to a halt. A young man, beardless though hard-eyed beneath the iron of his helm. More crowded in behind him, spilling out into the killing ground.

The Red Sister tilted her head to acknowledge them.

Then it began.

1 (#ulink_9fe49731-e1e7-52a4-91cf-a29f68eff9ae)

No child truly believes they will be hanged. Even on the gallows platform with the rope scratching at their wrists and the shadow of the noose upon their face they know that someone will step forward, a mother, a father returned from some long absence, a king dispensing justice … someone. Few children have lived long enough to understand the world into which they were born. Perhaps few adults have either, but they at least have learned some bitter lessons.

Saida climbed the scaffold steps as she had climbed the wooden rungs to the Caltess attic so many times. They all slept there together, the youngest workers, bedding down among the sacks and dust and spiders. They would all climb those rungs tonight and whisper about her in the darkness. Tomorrow night the whispers would be spent and a new boy or girl would fill the empty space she left beneath the eaves.

‘I didn’t do anything.’ Saida said it without hope, her tears dry now. The wind sliced cold from the west, a Corridor wind, and the sun burned red, filling half the sky yet offering little heat. Her last day?

The guard prodded her on, indifferent rather than unkind. She looked back at him, tall, old, flesh tight as if the wind had worn it down to the bone. Another step, the noose dangling, dark against the sun. The prison yard lay near-deserted, a handful watching from the black shadows where the outer wall offered shelter, old women, grey hair trailing. Saida wondered what drew them. Perhaps being so old they worried about dying and wanted to see how it was done.

‘I didn’t do it. It was Nona. She even said so.’ She had spoken the words so many times that meaning had leached away leaving them just pale noise. But it was true. All of it. Even Nona said so.

The hangman offered Saida the thinnest of smiles and bent to check the rope confining her wrists. It itched and it was too tight, her arm hurt where Raymel had cracked it, but Saida said nothing, only scanned the yard, the doors to the cell blocks, the outer buildings, even the great gates to the world outside. Someone would come.

A door clanged open from the Pivot, a squat tower where the warden was said to live in luxury to rival any lord’s. A guardsman emerged, squinting against the sun. Just a guardsman: the hope, that had leapt so easily in Saida’s breast, crashed once more.

Stepping from behind the guardsman a smaller, wider figure. Saida looked again, hoping again. A woman in the long habit of a nun came walking into the yard. Only the staff in her hand, its end curled and golden, marked her office.

The hangman glanced across, his narrow smile replaced by a broad frown. ‘The abbess …’

‘I ain’t seen her down here before.’ The old guardsman tightened his fingers on Saida’s shoulder.

Saida opened her mouth but found it too dry for her thoughts. The abbess had come for her. Come to take her to the Ancestor’s convent. Come to give her a new name and a new place. Saida wasn’t even surprised. She had never truly thought she would be hanged.

2 (#ulink_9b535f79-3f87-5d33-b2a9-0f9f0653098c)

The stench of a prison is an honest one. The guards’ euphemisms, the public smile of the chief warden, even the building’s façade, may lie and lie again, but the stink is the unvarnished truth: sewage and rot, infection and despair. Even so, Harriton prison smelled sweeter than many. A hanging prison like Harriton doesn’t give its inmates the chance to rot. A brief stay, a long drop on a short rope, and they could feed the worms at their leisure in a convict ditch-grave up at the paupers’ cemetery in Winscon.

The smell bothered Argus when he first joined the guard. They say that after a while your mind steps around any smell without noticing. It’s true, but it’s also true of pretty much every other bad thing in life. After ten years Argus’s mind stepped around the business of stretching people’s necks just as easily as it had acclimatized to Harriton’s stink.

‘When you leaving?’ Dava’s obsession with everyone else’s schedule used to annoy Argus, but now he just answered without thought or memory. ‘Seventh bell.’

‘Seventh!’ The little woman rattled out her usual outrage at the inequities of the work rota. They ambled towards the main holding block, the private scaffold at their back. Behind them Jame Lender dangled out of sight beneath the trapdoor, still twitching. Jame was the graveman’s problem now. Old Man Herber would be along soon enough with his cart and donkey for the day’s take. The short distance to Winscon Hill might prove a long trip for Old Herber, his five passengers, and the donkey, near as geriatric as its master. The fact that Jame had no meat on him to speak of would lighten the load. That, and the fact two of the other four were small girls.

Herber would wind his way through the Cutter Streets and up to the Academy first, selling off whatever body parts might have a value today. What he added to the grave-ditch up on the Hill would likely be much diminished – a collection of wet ruins if the day’s business had been good.

‘… sixth bell yesterday, fifth the day before.’ Dava paused the rant that had sustained her for years, an enduring sense of injustice that gave her the backbone to handle condemned men twice her size.

‘Who’s that?’ A tall figure was knocking at the door to the new arrivals’ block with a heavy cane.

‘Fellow from the Caltess? You know.’ Dava snapped her fingers before her face as if trying to surprise the answer out. ‘Runs fighters.’

‘Partnis Reeve!’ Argus called the name as he remembered it and the big man turned. ‘Been a while.’

Partnis visited the day-gaol often enough to get his fighters out of trouble. You don’t run a stable of angry and violent men without them breaking a few faces off the payroll from time to time, but generally they didn’t end up at Harriton. Professional fighters usually keep a calm enough head to stop short of killing during their bar fights. It’s the amateurs who lose their minds and keep stamping on a fallen opponent until there’s nothing left but mush.

‘My friend!’ Partnis turned with arms wide, a broad smile, and no attempt at Argus’s name. ‘I’m here for my girl.’

‘Your girl?’ Argus frowned. ‘Didn’t know you were a family man.’

‘Indentured. A worker.’ Partnis waved the matter aside. ‘Open the door, will you, good fellow. She’s down to drop today and I’m late enough as it is.’ He frowned, as if remembering some sequence of irritating delays.

Argus lifted the key from his pocket, a heavy piece of ironwork. ‘Probably missed her already, Partnis. Sun’s a-setting. Old Herber and his cart will be creaking down the alleys, ready for his take.’

‘Both of them creaking, eh? Herber and his cart,’ Dava put in. Always quick with a joke, never funny.

‘I sent a runner,’ Partnis said, ‘with instructions that the Caltess girls shouldn’t be dropped before—’

‘Instructions?’ Argus paused, key in the lock.

‘Suggestions, then. Suggestions wrapped around a silver coin.’

‘Ah.’ Argus turned the key and led him inside. He took his visitor by the quickest route, through the guard station, along the short corridor where the day’s arrivals watched from the narrow windows in their cell doors, and out into the courtyard where the public scaffold sat below the warden’s window.

The main gates had already opened, ready to admit the graveman’s cart. A small figure waited close to the scaffold steps, a single guardsman beside her, John Fallon by the look of it.

‘Just in time!’ Argus said.

‘Good.’ Partnis started forward, then faltered. ‘Isn’t that …’ he trailed off, lips curling into a snarl of frustration.

Following the tall man’s gaze, Argus spotted the source of his distress. The Abbess of Sweet Mercy came striding through the small crowd of onlookers before the warden’s steps. At this distance she could be anyone’s mother, a shortish, plumpish figure swathed in black cloth, but her crozier announced her.

‘Dear heavens, that awful old witch has come to steal from me yet again.’ Partnis both lengthened and quickened his stride, forcing Argus into an undignified jog to keep pace. Dava, on the man’s other side, had to run.

Despite Partnis’s haste, he beat the abbess to the girl by only a fraction. ‘Where’s the other one?’ He looked around as if the guardsman might be hiding another prisoner behind him.

‘Other what?’ John Fallon’s gaze flickered past Partnis to the advancing nun, her habit swirling as she marched.

‘Girl! There were two. I gave orders to— I sent a request that they be held back.’

‘Over with the dropped.’ Fallon tilted his head towards a mound beside the main gates, several feet high. Stones pinned a stained, grey sheet across the heap. The graveman’s cart came into view as they watched.

‘Damnation!’ The word burst from Partnis loud enough to turn heads all across the yard. He raised both hands, fingers spread, then trembling with effort, lowered them to his sides. ‘I wanted them both.’

‘Have to argue with the graveman over the big one,’ Fallon observed. ‘This’un.’ He reached for the girl at his side. ‘You’ll have to argue with me over. Then those two.’ He nodded at Dava and Argus. ‘Then the warden.’

‘There’ll be no arguing.’ The abbess stepped between Fallon and Partnis, dwarfed by both, her crozier reaching up to break their eye contact. ‘I shall be taking the child.’

‘No you won’t!’ Partnis looked down at her, brow furrowed. ‘All due respect to the Ancestor and all that, but she’s mine, bought and paid for.’ He glanced back at the gates where Herber had now halted his cart beside the covered mound. ‘Besides … how do you know she’s the one you want?’

The abbess snorted and favoured Partnis with a motherly smile. ‘Of course she is. You can tell by looking at her, Partnis Reeve. This child has the fire in her eyes.’ She frowned. ‘I saw the other. Scared. Lost. She should never have been here.’

‘Saida’s back in the cells …’ the girl said. ‘They told me I would go first.’

Argus peered at the child. A small thing in shapeless linen – not street rags, covered in rusty stains, but a serf’s wear none the less. She might be nine. Argus had lost the knack for telling. His older two were long grown, and little Sali would always be five. This girl was a fierce creature, a scowl on her thin, dirty face. Eyes black below a short shock of ebony hair.

‘Might have been the other,’ Partnis said. ‘She was the big one.’ He lacked conviction. A fight-master knows the fire when he sees it.

‘Where’s Saida?’ the girl asked.

The abbess’s eyes widened a fraction. It almost looked like hurt. Gone, quicker than the shadow of a bird’s wing. Argus decided he imagined it. The Abbess of Sweet Mercy was called many things, few of them to her face, and ‘soft’ wasn’t one of them.

‘Where’s my friend?’ the girl repeated.

‘Is that why you stayed?’ the abbess asked. She pulled a hoare-apple from her habit, so dark a red it could almost be black, a bitter and woody thing. A mule might eat one – few men would.

‘Stayed?’ Dava asked, though the question hadn’t been pointed her way. ‘She stayed ’cos this is a bloody prison and she’s tied and under guard!’

‘Did you stay to help your friend?’

The girl didn’t answer, only glared up at the woman as if at any moment she might leap upon her.

‘Catch.’ The abbess tossed the apple towards the girl.

Quick as quick a small hand intercepted it. Apple smacking into palm. Behind the girl a length of rope dropped to the ground.

‘Catch.’ The abbess had another apple in hand and threw it, hard.

The girl caught it in her other hand.

‘Catch.’

Quite where the abbess had hidden her fruit supply Argus couldn’t tell, but he stopped caring a heartbeat later, staring at the third apple, trapped between two hands, each full of the previous two.

‘Catch.’ The abbess tossed yet another hoare-apple, but the girl dropped her three and let the fourth sail over her shoulder.

‘Where’s Saida?’

‘You come with me, Nona Grey,’ the abbess said, her expression kindly. ‘We will discuss Saida at the convent.’

‘I’m keeping her.’ Partnis stepped towards the girl. ‘A treasured daughter! Besides, she damn near killed Raymel Tacsis. The family will never let her go free. But if I can show she has value they might let me put her into a few fights first.’

‘Raymel’s dead. I killed him. I—’

‘Treasured? I’m surprised you let her go, Mr Reeve,’ the abbess cut across the girl’s protests.

‘I wouldn’t have if I’d been there!’ Partnis clenched his hand as if trying to recapture the opportunity. ‘I was halfway across the city when I heard. Got back to find the place in chaos … blood everywhere … Tacsis men waiting … If the city guard hadn’t hauled her up here she’d be in Thuran’s private dungeon by now. He’s not a man to lose a son and sit idle.’

‘Which is why you will give her to me.’ The abbess’s smile reminded Argus of his mother’s. The one she’d use when she was right and they both knew it. ‘Your pockets aren’t deep enough to get young Nona out of here should the Tacsis boy die, and if you did obtain her release neither you nor your establishment are sufficiently robust to withstand Thuran Tacsis’s demands for retribution.’

The girl tried to interrupt. ‘How do you know my name? I didn’t—’

‘Whereas I have been friends with Warden James longer than you have been alive, Mr Reeve.’ The abbess cut across the girl again. ‘And no sane man would mount an attack on a convent of the faith.’

‘You shouldn’t take her for a Red Sister.’ Partnis had that sullen tone men get when they know they’ve lost. ‘It’s not right. She’s got no Ancestor faith … and she’s all but a murderer. Vicious, it was, the way they tell it …’

‘Faith I can give her. What she’s got already is what the Red Sisters need.’ The abbess reached out a plump hand towards the girl. ‘Come, Nona.’

Nona glanced up at John Fallon, at Partnis Reeve, at the hangman and the noose swaying beside him. ‘Saida is my friend. If you’ve hurt her I’ll kill you all.’

In silence she walked forward, placing her feet so as not to step on the fallen apples, and took the abbess’s hand.

Argus and the others watched them leave. At the gates, they paused, black against the red sun. The child released the abbess’s hand and took three paces towards the covered mound. Old Herber and his mule stood, watching, as bound by the moment as the rest of them. Nona stopped, staring at the mound. She looked towards the men at the gallows – a long, slow look – then returned to the abbess. Seconds later the pair had vanished around the corner.

‘Marking us for death she was,’ Dava said.

Still joking. Still not funny.

3 (#ulink_433c3823-d39e-592a-86c1-68ac56bfed40)

A juggler once came to Nona’s village, a place so small it had neither a name nor a market square. The juggler came dressed in mud and faded motley, a lean look about him. He came alone, a young man, dark eyes, quick hands. In a sackcloth bag he carried balls of coloured leather, batons with white and black ribbons, and crudely made knives.

‘Come, watch, the great Amondo will delight and amaze.’ It sounded like a phrase he didn’t own. He introduced himself to the handful of villagers not labouring in field or hut and yet brave enough to face a Corridor wind laced with icy rain. Laying his hat between them, broad-brimmed and yawning for appreciation, he reached for four striped batons and set them dancing in the air.

Amondo stayed three days, though his audience dried up after the first hour of the first evening. The sad fact is that there’s only so much entertainment to be had from one man juggling, however impressive he might be.

Nona stayed by him though, watching every move, each deft tuck and curl and switch. She stayed even after the light failed and the last of the children drifted away. Silent and staring she watched as the juggler started to pack his props into their bag.

‘You’re a quiet one.’ Amondo threw her a wizened apple that sat in his hat along with several better examples, two bread rolls, a piece of Kennal’s hard goat’s cheese, and somewhere amongst them a copper halfpenny clipped back to a quarter.

Nona held the apple close to her ear, listening to the sound of her fingers against its wrinkles. ‘The children don’t like me.’

‘No?’

‘No.’

Amondo waited, juggling invisible balls with his hands.

‘They say I’m evil.’

Amondo dropped an invisible ball. He left the others to fall and raised a brow.

‘Mother says they say it because my hair is so black and my skin is so pale. She says I get my skin from her and my hair from my da.’ The other children had the tan skin and sandy hair of their parents, but Nona’s mother had come from the ice fringes and her father’s clan hunted up on the glaciers, strangers both of them. ‘Mother says they just don’t like different.’

‘Those are ugly ideas for children to have in their heads.’ The juggler picked up his bag.

Nona stood, watching the apple in her hand but not seeing it. The memory held her. Her mother, in the dimness of their hut, noticing the blood on her hands for the first time. What’s that? Did they hurt you? Nona had hung her head and shook it. Billem Smithson tried to hurt me. This was inside him.

‘Best get along home to your ma and pa.’ Amondo turned slowly, scanning the huts, the trees, the barns.

‘My da’s dead. The ice took him.’

‘Well then.’ A smile, only half-sad. ‘I’d best take you home.’ He pushed back the length of his hair and offered his hand. ‘We’re friends, aren’t we?’

Nona’s mother let Amondo sleep in their barn, though it wasn’t really more than a shed for the sheep to hide in when the snows came. She said people would talk but that she didn’t care. Nona didn’t understand why anyone would care about talk. It was just noise.

On the night Amondo left, Nona went to see him in the barn. He had spread the contents of his bag before him on the dirt floor, where the red light of the moon spilled in through the doorway.

‘Show me how to juggle,’ she said.

He looked up from his knives and grinned, dark hair swept down across his face, dark eyes behind. ‘It’s difficult. How old are you?’

Nona shrugged. ‘Little.’ They didn’t count years in the village. You were a baby, then little, then big, then old, then dead.

‘Little is quite small.’ He pursed his lips. ‘I’ve two years and twenty. I guess I’m supposed to be big.’ He smiled but with more worry in it than joy, as if the world made no more sense and offered no more comfort to bigs than littles. ‘Let’s have a go.’

Amondo picked up three of the leather balls. The moonlight made it difficult to see their colours but with focus approaching it was bright enough to throw and catch. He yawned and rolled his shoulders. A quick flurry of hands and the three balls were dancing in their interlaced arcs. ‘There.’ He caught them. ‘You try.’

Nona took the balls from the juggler’s hands. Few of the other children had managed with two. Three balls was a dismissal. Amondo watched her turning them in her hands, understanding their weight and feel.

She had studied the juggler since his arrival. Now she visualized the pattern the balls had made in the air, the rhythm of his hands. She tossed the first ball up on the necessary curve and slowed the world around her. Then the second ball, lazily departing her hand. A moment later all three were dancing to her tune.

‘Impressive!’ Amondo got to his feet. ‘Who taught you?’

Nona frowned and almost missed her catch. ‘You did.’

‘Don’t lie to me, girl.’ He threw her a fourth ball, brown leather with a blue band.

Nona caught it, tossed it, struggled to adjust her pattern and within a heartbeat she had all four in motion, arcing above her in long and lazy loops.

The anger on Amondo’s face took her by surprise. She had thought he would be pleased – that it would make him like her. He had said they were friends but she had never had a friend and he said it so lightly … She had thought that sharing this might make him say the words again and seal the matter into the world. Friend. She fumbled a ball to the floor on purpose then made a clumsy swing at the next.

‘A circus man taught me,’ she lied. The balls rolled away from her into the dark corners where the rats live. ‘I practise. Every day! With … stones … smooth ones from the stream.’

Amondo closed off his anger, putting a brittle smile on his face. ‘Nobody likes to be made a fool of, Nona. Even fools don’t like it.’

‘How many can you juggle?’ she asked. Men like to talk about themselves and their achievements. Nona knew that much about men even if she was little.

‘Goodnight, Nona.’

And, dismissed, Nona had hurried back to the two-room hut she shared with her mother, with the light of the moon’s focus blazing all about her, warmer than the noon-day sun.

‘Faster, girl!’ The abbess jerked Nona’s arm, pulling her out of her memories. The hoare-apples had put Amondo back into her mind. The woman glanced over her shoulder. A moment later she did it again. ‘Quickly!’

‘Why?’ Nona asked, quickening her pace.

‘Because Warden James will have his men out after us soon enough. Me they’ll scold – you they’ll hang. So pick those feet up!’

‘You said you’d been friends with the warden since before Partnis Reeve was a baby!’

‘So you were listening.’ The abbess steered them up a narrow alley, so steep it required a step or two every few yards and the roofs of the tall houses stepped one above the next to keep pace. The smell of leather hit Nona, reminding her of the coloured balls Amondo had handed her, as strong a smell as the stink of cows, rich, deep, polished, brown.

‘You said you and the warden were friends,’ Nona said again.

‘I’ve met him a few times,’ the abbess replied. ‘Nasty little man, bald and squinty, uglier on the inside.’ She stepped around the wares of a cobbler, laid out before his steps. Every other house seemed to be a cobbler’s shop, with an old man or young woman in the window, hammering away at boot heels or trimming leather.

‘You lied!’

‘To call something a lie, child, is an unhelpful characterization.’ The abbess drew a deep breath, labouring up the slope. ‘Words are steps along a path: the important thing is to get where you’re going. You can play by all manner of rules, step-on-a-crack-break-your-back, but you’ll get there quicker if you pick the most certain route.’

‘But—’

‘Lies are complex things. Best not to bother thinking in terms of truth or lie – let necessity be your mother … and invent!’

‘You’re not a nun!’ Nona wrenched her hand away. ‘And you let them kill Saida!’

‘If I had saved her then I would have had to leave you.’

Shouts rang out somewhere down the steepness of the alley.

‘Quickly.’ The alley gave onto a broad thoroughfare by a narrow flight of stairs and the abbess turned onto it, not pausing now to glance back.

‘They know where we’re going.’ Nona had done a lot of running and hiding in her short life and she knew enough to know it didn’t matter how fast you went if they knew where to find you.

‘They know when we get there they can’t follow.’

People choked the street but the abbess wove a path through the thickest of the crowd. Nona followed, so close that the tails of the nun’s habit flapped about her. Crowds unnerved her. There hadn’t been as many people in her village, nor in her whole world, as pressed into this street. And the variety of them, some adults hardly taller than she was, others overtopping even the hulking giants who fought at the Caltess. Some dark, their skin black as ink, some white-blond and so pale as to show each vein in blue, and every shade between.

Through the alleys rising to join the street Nona saw a sea of roofs, tiled in terracotta, stubbled with innumerable chimneys, smoke drifting. She had never imagined a place so big, so many people crammed so tight. Since the night the child-taker had driven Nona and his other purchases into Verity she had seen almost nothing of the city, just the combat hall, the compound where the fighters lived, and the training yards. The cart-ride to Harriton had offered only glimpses as she and Saida sat hugging each other.

‘Through here.’ The abbess set a hand on Nona’s shoulder and aimed her at the steps to what looked like a pillared temple, great doors standing open, each studded with a hundred circles of bronze.

The steps were high enough to put an ache in Nona’s legs. At the top a cavernous hall waited, lit by high windows, every square foot of it packed with stalls and people hunting bargains. The sound of their trading, echoing and multiplied by the marble vaults above, spoke through the entrance with one many-tongued voice. For several minutes it was nothing but noise and colour and pushing. Nona concentrated on filling the void left as the abbess stepped forward before some other body could occupy the space. At last they stumbled into a cool corridor and out into a quieter street behind the market hall.

‘Who are you?’ Nona asked. She had followed the woman far enough. ‘And,’ realizing something, ‘where’s your stick?’

The abbess turned, one hand knotted in the string of purple beads around her neck. ‘My name is Glass. That’s Abbess Glass to you. And I gave my crozier to a rather surprised young man shortly after we emerged from Shoe Street. I hope the warden’s guards followed it rather than us.’

‘Glass isn’t a proper name. It’s a thing. I’ve seen some in Partnis Reeve’s office.’ Something hard and near invisible that kept the Corridor winds from the fight-master’s den.

Abbess Glass turned away and resumed her marching. ‘Each sister takes a new name when she is deemed fit to marry the Ancestor. It’s always the name of an object or thing, to set us apart from the worldly.’

‘Oh.’ Most in Nona’s village had prayed to the nameless gods of rain and sun as they did all across the Grey, setting corn dollies in the fields to encourage a good harvest. But her mother and a few of the younger women went to the new church over in White Lake, where a fierce young man talked about the god who would save them, the Hope, rushing towards us even now. The roof of the Hope church stood ever open so they could see the god advancing. To Nona he looked like all the other stars, only white where almost every other is red, and brighter too. She had asked if all the other stars were gods as well, but all that earned her was a slap. Preacher Mickel said the star was Hope, and also the One God, and that before the northern ice and the southern ice joined hands he would come to save the faithful.

In the cities, though, they mainly prayed to the Ancestor.

‘There. See it?’

Nona followed the line of the abbess’s finger. On a high plateau, beyond the city wall, the slanting sunlight caught on a domed building, perhaps five miles off.

‘Yes.’

‘That’s where we’re headed.’ And the abbess led away along the street, stepping around a horse pile too fresh for the garden-boys to have got to yet.

‘You didn’t hear about me all the way up there?’ Nona asked. It didn’t seem possible.

Abbess Glass laughed, a warm and infectious noise. ‘Ha! No. I had other business in town. One of the faithful told me your story and I made a diversion on my way back to the convent.’

‘Then how did you know my name? My real name, not the one Partnis gave me.’

‘Could you have caught the fourth apple?’ The abbess responded with a question.

‘How many apples can you catch, old woman?’

‘As many as I need to.’ Abbess Glass looked back at her. ‘Hurry up, now.’

Nona knew that she didn’t know much, but she knew when someone was trying to take her measure and she didn’t like things being taken from her. The abbess would have kept on with her apples until she found Nona’s limit – and held that knowledge like a knife in its sheath. Nona hurried up and said nothing. The streets grew emptier as they approached the city wall and the shadows started to stretch.

Alleyways yawned left and right, dark mouths ready to swallow Nona whole. However warm the abbess’s laughter, Nona didn’t trust her. She had watched Saida die. Running away was still very much an option. Living with a collection of old nuns on a windswept hill outside the city might be better than hanging, but not by much.

‘Master Reeve said that Raymel wasn’t dead. That’s not true.’

The abbess pulled her coif off in a smooth motion, revealing short grey hair and exposing her neck to the wind. She quickly threw a shawl of sequined wool about her shoulders.

‘Where did— You stole that!’ Nona glanced around to see if any of the passers-by would share her outrage but they were few and far between, heads bowed, bound to their own purposes. ‘A thief and a liar!’

‘I value my integrity.’ The abbess smiled. ‘Which is why it has a price.’

‘A thief and a liar.’ Nona decided that she would run.

‘And you, child, appear to be complaining because the man you were to hang for murdering is not in fact dead.’ Abbess Glass tied the shawl and tugged it into place. ‘Perhaps you can explain what happened at the Caltess and I can explain what Partnis Reeve almost certainly meant about Raymel Tacsis.’

‘I killed him.’ The abbess wanted a story but Nona kept her words close. She had come to talking so late her mother had thought her dumb, and even now she preferred to listen.

‘How? Why? Paint me a picture.’ Abbess Glass made a sharp turn, pulling Nona through a passage so narrow that a few more pounds about her middle would see the nun scraping both sides.

‘They brought us to the Caltess in a cage.’ Nona remembered the journey. There had been three children on the wagon when Giljohn, the child-taker, stopped at her village and the people gave her over. Grey Stephen had passed her up to him. It seemed that everyone she knew watched as Giljohn put her in the wooden cage with the others. The village children, both littles and bigs, looked on mute, the old women muttered, Mari Streams, her mother’s friend, had sobbed; Martha Baker had shouted cruel words. When the wagon jolted off along its way stones and clods of mud had followed. ‘I didn’t like it.’

The wagon had rattled on for days, then weeks. In two months they had covered nearly a thousand miles, most of it on small and winding lanes, back and forth across the same ground. They rattled up and down the Corridor, weaving a drunkard’s trail north and south, so close to the ice that sometimes Nona could see the walls rising blue above the trees. The wind proved the only constant, crossing the land without friendship, a stranger’s fingers trailing the grass, a cold intrusion.

Day after day Giljohn steered his wagon from town to town, village to hamlet to lonely hovel. The children given up were gaunt, some little more than bones and rags, their parents lacking the will or coin to feed them. Giljohn delivered two meals a day, barley soup with onions in the morning, hot and salted, with hard black bread to dip. In the evening, mashed swede with butter. His passengers looked better by the day.

‘I’ve seen more meat on a butcher’s apron.’ That’s what Giljohn told Saida’s parents when they brought her out of their hut into the rain.

The father, a ratty little man, stooped and gone to grey, pinched Saida’s arm. ‘Big girl for her age. Strong. Got a lick o’ gerant in her.’

The mother, whey-faced, stick-thin, weeping, reached to touch Saida’s long hair but let her hand fall away before contact was made.

‘Four pennies, and my horse can graze in your field tonight.’ Giljohn always dickered. He seemed to do it for the love of the game, his purse being the fattest Nona had ever seen, crammed with pennies, crowns, even a gleaming sovereign that brought a new colour into Nona’s life. In the village only Grey Stephen ever had coins. And James Baker that time he sold all his bread to a merchant’s party that had lost the track to Gentry. But none of them had ever had gold. Not even silver.

‘Ten and you get on your way before the hour’s old,’ the father countered.

Within the aforementioned hour Saida had joined them in the cage, her pale hair veiling a down-turned face. The cart moved off without delay, heavier one girl and lighter five pennies. Nona watched through the bars, the father counting the coins over and again as if they might multiply in his hand, his wife clutching at herself. The mother’s wailing followed them as far as the cross-roads.

‘How old are you?’ Markus, a solid dark-haired boy who seemed very proud of his ten years, asked the question. He’d asked Nona the same when she joined them. She’d said nine because he seemed to need a number.

‘Eight.’ Saida sniffed and wiped her nose with a muddy hand.

‘Eight? Hope’s blood! I thought you were thirteen!’ Markus seemed in equal measure both pleased to keep his place as oldest, and outraged by Saida’s size.

‘Gerant in her,’ offered Chara, a dark girl with hair so short her scalp shone through.

Nona didn’t know what gerant was, except that if you had it you’d be big.

Saida shuffled closer to Nona. As a farm-girl she knew not to sit above the wheels if you didn’t want your teeth rattled out.

‘Don’t sit by her,’ Markus said. ‘Cursed, that one is.’

‘She came with blood on her,’ Chara said. The others nodded.

Markus delivered the final and most damning verdict. ‘No charge.’

Nona couldn’t argue. Even Hessa with her withered leg had cost Giljohn a clipped penny. She shrugged and brought her knees up to her chest.

Saida pushed aside her hair, sniffed mightily, and threw a thick arm about Nona drawing her close. Alarmed, Nona had pushed back but there was no resisting the bigger girl’s strength. They held like that as the wagon jolted beneath them, Saida weeping, and when the girl finally released her Nona found her own eyes full of tears, though she couldn’t say why. Perhaps the piece of her that should know the answer was broken.

Nona knew she should say something but couldn’t find the right words. Maybe she’d left them in the village, on her mother’s floor. Instead of silence she chose to say the thing that she had said only once before – the thing that had put her in the cage.

‘You’re my friend.’

The big girl sniffed, wiped her nose again, looked up, and split her dirty face with a white grin.

Giljohn fed them well and answered questions, at least the first time they were asked – which meant ‘are we there yet?’ and ‘how much further?’ merited no more reply than the clatter of wheels.

The cage served two purposes, both of which he explained once, turning his grizzled face back to the children to do so and letting the mule, Four-Foot, choose his own direction.

‘Children are like cats, only less useful and less furry. The cage keeps you in one place or I’d forever be rounding you up. Also …’ he raised a finger to the pale line of scar tissue that divided his left eyebrow, eye-socket, and cheekbone, ‘I am a man of short temper and long regret. Irk me and I will lash out with this, or this.’ He held out first the cane with which he encouraged Four-Foot, and then the callused width of his palm. ‘I shall then regret both the sins against the Ancestor and against my purse.’ He grinned, showing yellow teeth and dark gaps. ‘The cage saves you from my intemperance. At least until you irk me to a level where my ire lasts the trip around to the door.’

The cage could hold twelve children. More if they were small. Giljohn continued his meander westward along the Corridor, whistling in fair weather, hunched and cursing in foul.

‘I’ll stop when my purse is empty or my wagon’s full.’ He said it each time a new acquisition joined them, and it set Nona to wishing Giljohn would find some golden child whose parents loved her and who would cost him every coin in his possession. Then at last they might get to the city.

Sometimes they saw it in the distance, the smoke of Verity. Closer still and a faint suggestion of towers might resolve from the haze above the city. Once they came so close that Nona saw the sunlight crimson on the battlements of the fortress that the emperors had built around the Ark. Beneath it, the whole sprawling city bound about with thick walls and sheltering from the wind in the lee of a high plateau. But Giljohn turned and the city dwindled once more to a distant smudge of smoke.

Nona whispered her hope to Saida on a cold day when the sun burned scarlet over half the sky and the wind ran its fingers through the wooden bars, finding strange and hollow notes.

‘Giljohn doesn’t want pretty,’ Saida snorted. ‘He’s looking for breeds.’

Nona only blinked.

‘Breeds. You know. Anyone who shows the blood.’ She looked down at Nona, still wide-eyed with incomprehension. ‘The four tribes?’

Nona had heard of them, the four tribes of men who came to the world out of darkness and mixed their lines to bear children who might withstand the harshness of the lands they claimed. ‘Ma took me to the Hope church. They didn’t like talk of the Ancestor.’

Saida held her hands up. ‘Well there were four tribes.’ She counted them off on her fingers. ‘Gerant. If you have too much gerant blood you get big like they were.’ She patted her broad chest. ‘Hunska. They’re less common.’ She touched Nona’s hair. ‘Hunska-dark, hunska-fast.’ As if reciting a rhyme. ‘The others are even rarer. Marjool … and … and …’

‘Quantal,’ Markus said from the corner. He snorted and puffed up as if he were an elder. ‘And it’s marjal, not marjool.’

Saida scowled at him, and turning back she lowered her voice to a whisper. ‘They can do magic.’

Nona touched her hair where Saida’s hand had rested. The village littles thought black hair made her evil. ‘Why does Giljohn want children like that?’

‘To sell.’ Saida shrugged. ‘He knows the signs to look for. If he’s right he can sell us for more than he paid. Ma said I’ll find work if I keep getting big. She said in the city they feed you meat and pay you coins.’ She sighed. ‘I still don’t want to go.’

Giljohn took the lanes that led nowhere, the roads so rutted and overgrown that often it needed all the children pushing and Four-Foot straining all four legs to make headway. Giljohn would let Markus lead the mule then – Markus had a way with the beast. The children liked Four-Foot, he smelled worse than an old blanket and had a fondness for nipping legs, but he drew them tirelessly and his only competition for their affection was Giljohn. Several of them fought to bring him hoare-apples and sweet grass at the day’s end. But, of all of them Four-Foot only loved Giljohn who whipped him, and Markus who rubbed him between the eyes and spoke the right kind of nonsense when doing it.

The rains came for days at a time making life in the cage miserable, though Giljohn did throw a hide over the top and windward side. The mud was the worst of it, cold and sour stuff that took hold of the wheels so that they all had to shove. Nona hated the mud: lacking Saida’s height she often found herself thigh-deep in the cold and sucking mire, having to be rescued by Giljohn as the wagon slurped onto firmer ground. Each time he would knot his fist in the back of her hempen smock and heft her out bodily.

Nona set to scraping the goo off as soon as he set her down on the tailgate.

‘What’s a bit of mud to a farm-girl?’ Giljohn wanted to know.

Nona only scowled and kept on scraping. She hated being dirty, always had. Her mother said she ate her food like a highborn lady, holding each morsel with precision so as not to smear herself.

‘She’s not a farm-girl.’ Saida spoke up for her. ‘Nona’s ma wove baskets.’

Giljohn returned to the driver’s seat. ‘She’s not anything now, and neither are the rest of you until I sell you. Just mouths to feed.’

Roads that led nowhere took them to people who had nothing. Giljohn never asked to buy a child. He’d pull up alongside any farm that grew more weeds and rocks than crop, places where calling the harvest ‘failed’ would be over generous, implying that it had made some sort of effort to succeed. In such places the tenant farmer might pause his plough or lay down his scythe to approach the wagon at his boundary wall.

A man driving a wagonload of children in a cage doesn’t have to state his business. A farmer whose flesh lies sunken around his bones, and whose eyes are the colour of hunger, doesn’t have to explain himself if he walks up to such a man. Hunger lies beneath all of our ugliest transactions.

Sometimes a farmer would make that long, slow crossing of his field, from right to wrong, and stand, lean in his overalls, chewing on a corn stalk, eyes a-glitter in the shadows of his face. On such occasions it wouldn’t take more than a few minutes before a string of dirty children were lined up beside him, graduated in height from those narrowing their eyes against the suspicion of what they’d been summoned for, down to those still clutching in one hand the stick they’d been playing with and in the other the rags about their middle, their eyes wide and without guile.

Giljohn picked out any child with possible gerant traits on a swift first pass. When they knew their ages it was easier, but even without anything more than a rough guess at a child’s years he would find clues to help him. Often he looked at the backs of their necks, or took their wrists and bent them back – just until they winced. Those children he would set aside. On a second pass he would examine the eyes, pulling at the corners and peering at the whites. Nona remembered those hands. She had felt like a pear picked from the market stall, squeezed, sniffed over, replaced. The village had asked nothing for her, yet still Giljohn had carried out his checks. A space in his cage and meals from his pot had to be earned.

With the hunska possibles the child-taker would rub the youngster’s hair between finger and thumb as if checking for coarseness. If still curious, he would test their swiftness by dropping a stone so that it fell behind a cloth he held out, and make a game of trying to catch it as it came back into view a couple of feet lower. Almost none of the children taken as hunska were truly fast: Giljohn said they’d grow into it, or training would bring their speed into the open.

Nona guessed they might make ten stops before finding someone prepared to swap their sons and daughters for a scattering of copper. She guessed that after walking the lines of children set out for him Giljohn would actually offer coins fewer than one time in a dozen, and that when he did it was generally for an over-large child. And even of these few hardly any, he said, would grow into full gerant heritage.

After Giljohn had picked out these and any dark and over-quick children, he would always return to the line for the third and slowest of his inspections. Here, although he watched with the hawk’s intensity, Giljohn kept his hands to himself. He asked questions instead.

‘Did you dream last night?’ he might ask.

‘Tell me … what colours do you see in the focus moon?’

And when they told him the moon is always red. When they said, that you can’t look at the focus moon, it will blind you, he replied, ‘But if you could, if it wasn’t, what colours would it be?’

‘What makes a blue sound?’ He often used that one.

‘What does pain taste of?’

‘Can you see the trees grow?’

‘What secrets do stones keep?’

And so on – sometimes growing excited, sometimes affecting boredom, yawning into his hand. All of it a game. Rarely won. And at the end of it, always the same, Giljohn crouched to be on their level. ‘Watch my finger,’ he would tell them. And he would move it through the air in a descending line, so close his nail almost clipped their nose. The line wavered, jerked, pulsed, beat, never the same twice but always familiar. What he was looking for in their eyes Nona didn’t know. He seldom seemed to find it though.

Two places in the wagon went to children selected in this final round, and each of those cost more than any of the others. Never too much though. Asked for gold he would walk away.

‘Friend, I’ve been at this as long as you’ve tilled these rows, and in all that time how many that I’ve sold on have passed beneath the Academy arch?’ he would ask. ‘Four. Only four full-bloods … and still they call me the mage-finder.’

In the long hours between one part of nowhere and the next the children, jolting in the cage, would watch the world pass by, much of it dreary moor, patchy fields, or dour forest where screw-pine and frost-oak fought for the sun, leaving little for the road. Mostly they were silent, for children’s chatter dies off soon enough if not fed, but Hessa proved a wonder. She would set her withered leg before her with both hands, then lean back against the wooden bars and tell story after story, her eyes closed above cheekbones so large they made something alien of her. In all her pinched face, framed by tight curls of straw-coloured hair, only her mouth moved. The stories she told stole the hours and pulled the children on journeys far longer than Four-Foot could ever manage. She had tales of the Scithrowl in the east and their battle-queen Adoma, and of her bargains with the horror that dwells beneath the black ice. She told of Durnishmen who sail across the Sea of Marn to the empire’s western shore in their sick-wood barges. Of the great waves sent up when the southern ice walls calve, and how they sweep the width of the Corridor to wash up against the frozen cliffs of the north, which collapse in turn and send back waves of their own. Hessa spoke of the emperor and his sisters, and of their bickering that had laid waste many a great family with the ill fortune to find itself between them. She told of heroes past and present, of olden day generals who held the border lands, of Admiral Scheer who lost a thousand ships, of Noi-Guin scaling castle walls to sink the knife, of Red Sisters in their battle-skins, of the Soft Men and their poisons …

Sometimes on those long roads Hessa spoke to Nona, huddled close in a corner of the cage, her voice low, and Nona couldn’t tell if it were a story or strange truths she told.

‘You see it too, don’t you, Nona?’ Hessa bent in close, so close her breath tickled Nona’s ear. ‘The Path, the line? The one that wants us to follow it.’

‘I don’t—’

‘I can walk in that place. Here they took my crutch and I have to crawl or be carried … but there … I can walk for as long as I can keep the Path beneath me.’ Nona felt the smile. Hessa moved back and laughed – rare for her, very rare. She told a story for everyone then, Persus and the Hidden Path, a tale from the oldest days, and even Giljohn leaned back to listen.

And one day, wonder of wonders, the twelfth child squeezed into the cage, and Giljohn declared his wagon full, his business complete. Turning west, he let Four-Foot lead the way to Verity, soon finding a wide and stone-clad road where four hooves could eat up the miles double quick.

They arrived in the dark and in the rain. Nona saw nothing more of the city than a multitude of lights, first a constellation hovering above the black threat of the great walls, and once through the yawn of the gates, a succession of islands where a lantern’s illumination pooled to offer a doorway here, a row of columns there, figures hidden in their cloaks, emerging from the blind night to be glimpsed and lost once more.

Broad streets and narrow, cut like canyons through the neck-craning height of Verity’s houses, brought the wagon in time to a tall timber door. A legend set in iron letters above the door declared a name, but recognizing that the shapes were letters took Nona to the borders of her education.

‘The Caltess, boys and girls.’ Giljohn pushed back his hood. ‘Time to meet Partnis Reeve.’

Giljohn pulled up in the courtyard that waited behind the high walls and ordered them out. Saida and Nona clambered down, stiff and sore. Before them a many-windowed hall rose to three times the height of any building that Nona had seen until she reached the city. The yard was largely deserted, lit by the flames guttering in a brazier set at the centre. Peculiar equipment lay abandoned in corners, including pieces of leather-bound wood the size and shape of men, set on round-bottomed bases. A few young men sat on benches beneath the lanterns, all of them polishing pieces of leatherwork, save one who was mending a net as if he were a fisherman.

Partnis Reeve kept the children lined up for more than an hour before he emerged from his hall. Long enough for dawn to infiltrate the yard and surprise Nona with the knowledge that a whole night had passed in travel.

Saida fidgeted and pulled her shawl about her. Nona watched as the sun edged the ridge of the hall’s black-tiled roof with crimson. Beyond the walls the city woke, creaking and groaning like an old man leaving his bed, though it had hardly slept.

Partnis came down the steps, always taking the next with the same leg. A heavy-featured man, tall and well fed, with iron-grey hair, dark eyes promising no kindness, wrapped against the cold in a thick velvet robe.

‘Partnis!’ Giljohn held his arms wide and Partnis Reeve copied the gesture, though neither man stepped forward into the promised embrace. ‘Celia well? And little Merra?’

‘Celia is … Celia.’ Partnis lowered his arms with a wry grin. ‘And Merra is living in Darrins Town, married to a cloth merchant’s boy.’

‘How did we get so old?’ Giljohn returned his arms to his sides. ‘Yesterday we were young.’

‘Yesterday was a long time ago.’ Partnis turned his attention to the merchandise. ‘Too small.’ He walked past Nona without further comment. ‘Too timid.’ He passed Saida. ‘Too fat. Too young. Too ill. Too lazy. Too clumsy. Too much trouble.’ He turned at the end of the line and looked at Giljohn. They were of a height, though Partnis looked soft where Giljohn looked hard. ‘I’ll give you two crowns for the lot.’

‘I spent two crowns feeding them!’ Giljohn spat on the grit floor.

The haggling took another hour and both men seemed to enjoy it. Giljohn enumerated the reasons why the children would become valuable fighters in Partnis’s contests, pointing out gerant or hunska traits.

‘This girl here is eight!’ Giljohn set a hand to Saida’s shoulder, making her flinch. ‘Eight years old! Tall as a tree. She’s a gerant prime for sure. A full-blood even!’

‘Even a full-blood’s only got labour value if there’s no fight in ’em.’ Partnis barked a wordless shout into Saida’s face. She stumbled back with a shriek of fear, raising both hands to her eyes. ‘Worthless.’

‘She’s eight, Partnis!’

‘So her father said. She looks fifteen to me.’

Giljohn grabbed Saida’s arm and pulled her forward. ‘Feel her wrists!’ He pushed her head forward and ran a finger over the vertebrae knobbling the back of her neck. ‘Look here!’ He straightened her by her hair. ‘Fathers lie, but bones don’t. This one’s a prime at the least. Ain’t seen a gerant to beat her this trip. Could be full-blood.’

Partnis took Saida’s wrist and squeezed until she whimpered. ‘She’s got a touch, I grant you.’

‘Touch? She’s no damn touch.’

‘Half-blood if you’re lucky.’

And so it went on, Partnis allowing some of the children might be a touch or even half-bloods, Giljohn insisting they were all primes or even full-bloods.

Nona and a boy named Tooram he claimed showed clear evidence of hunska bloodlines. He slapped Tooram, then tried again and the boy interposed his arm before the blow could land. When he tried it on Nona she let him slap her, the hard length of his hand impacting the side of her head, leaving her ear buzzing and her cheek one hot outrage of pain. He did it again, with a scowl, and she scowled back, making no effort to avoid the blow which took her off her feet and replaced the grey sky with bright and flashing lights.

‘… idiot.’

Nona found herself on her feet, her shoulder in Giljohn’s iron grip, blood filling her mouth. She remembered the force of the slap, how her teeth had seemed to rattle.

‘You saw how fast she turned towards me.’

It was true – Nona’s lips felt four times their size and white spears of pain lanced up her nose. She had faced into the blow at the last moment.

‘I must have missed that part,’ Partnis said.

Nona swallowed the blood. She let the pain run through her – the cost she paid for taking money from Giljohn’s pocket. Some of the children, sold by their own fathers, almost saw the child-taker as their replacement. Stern, certainly, but he fed them, kept them safe. Nona took a contrary view. Her father had died on the ice and what memories she kept of him warmed her in the cold, tasted sweet when the world ran sour. He would have known how to treat a man like Giljohn.

The gerants had no such choice to make, their size argued their case without need for demonstration. Though in Saida’s place Nona thought she might have agreed with Partnis when he accused her of being fifteen.

Partnis took them in exchange for ten crowns and two.

‘Be good.’ Giljohn, a father to them all for three long months, had no other words for them, climbing up behind Four-Foot without ceremony.

‘Goodbye.’ Saida was the only one to speak.

Giljohn glanced her way, stick half-raised for the off. ‘Goodbye,’ he said.

‘She meant the mule.’ Tooram didn’t turn his head, but he spoke loud enough for the words to reach.

A grin slanted across Giljohn’s face and, shaking his head, he flicked at Four-Foot’s haunches, encouraging him through the doors that Partnis’s man had set open once more.

Nona watched the wagon rattle off, Hessa, Markus, Willum and Chara staring back at her through the bars. She would miss Hessa and her stories. She wondered who Giljohn would sell her to and how a girl unable to walk would make her way in the world. She might miss Markus too, perhaps. The miles had worn away his sharp edges, the wheels had gone round and round … somehow turning him into someone she liked. In the next moment they were all gone.

‘And now you’re mine,’ Partnis said. He summoned the young man mending the net, lean but well-muscled under his woollen vest, hair dark, skin pale, but not so dark or so pale as Nona. ‘This is Jaymes. He’ll take you to Maya who is your mother now. The slapping kind.’ Partnis offered them a heavy smile. ‘I don’t expect to notice any of you until you’re this high.’ He held his hand to his chest. ‘And if I do, it will probably be bad news for you. Do what you’re told and you’ll be fine. You’re Caltess now. Bought and paid for.’

Maya stood more than a foot taller than Partnis, arms thick as a man’s thighs, her face red and blotched as if a constant rage held her in its jaws. To compensate for her complexion the Ancestor had given her thick blonde hair that she braided into heavy ropes. She stood on the attic ladder after shepherding the new arrivals up it, only her head and shoulders emerging into the gloom.

‘No lanterns up here. Ever. No candles. No lamps. Break that rule and I break you.’ She made the motion with heavy-knuckled hands. ‘When you’re not working you’re up here. Meals are in the kitchen. You’ll hear the bell when it’s time. Miss it and you won’t eat.’

Nona and the others crouched close to the trapdoor, watching the giant. The musty air reminded Nona of James Baker’s grain store at the village. Around them the shadows rustled. Cats most likely, rats and spiders of a certainty, but also other children watching the new arrivals.

Maya raised her voice. ‘Don’t pick on the new meat. There’s time enough for that down below.’ She stared at a patch of darkness seemingly no darker than any other. ‘I see any lumps and bumps on Partnis’s new purchases, Denam, Regol, and I’ll knock your heads together so hard you swap brains. Hear me?’ A pause. ‘Hear me?’ Loud enough to shake the roof.

‘I hear you.’ A snarl.

‘Heard.’ Chuckled in the distance.

The others emerged as soon as Maya withdrew. Two long-limbed boys dropped from the rafters into the midst of the newcomers. Nona hadn’t seen them lurking there. Others scampered in from the shadows, or strolled, or crept, each according to their nature. None of them as small or as young as Nona, but most of them not many years older. From the direction in which Maya had stared came a huge boy, a scowl beneath a thick shock of red hair, muscles heaped and shifting below his shapeless linen shift. Moments later a lad near as tall but willow-thin joined him, black hair sweeping down across his eyes, a crooked smile hung between the corners of his mouth.

A throng gathered, many more than Nona had anticipated. Huddled and watchful, waiting to be entertained.

The red-haired giant opened his mouth to threaten them. ‘You—’

‘Oh hush, Denam.’ The dark-haired boy stepped in front of him. ‘You’re newbies. I’m Regol. This is Denam, soon-to-be apprentice, and the toughest, fiercest warrior the Caltess attic has ever seen. Look at him wrong and he’ll chew you up then spit out the pieces.’ Regol glanced back at Denam. ‘That’s the gist, ain’t it?’ He returned his gaze to the newbies. ‘Now we’ve got the chest-thumping out of the way and saved Maya the bother of spanking Denam you can find yourself a place to sleep.’ He waved a hand airily at the gloom. ‘Don’t tread on any toes.’

Regol turned as if to go then paused. ‘Sooner rather than later someone will try to convince you that the reason so many of us up here are titchies like yourselves is that Partnis eats children, or there’s some test so deadly that almost nobody survives it, or sometimes Maya forgets to look before she sits down. The truth is that you’ve been bought early and cheap. Most of you will be disappointments. You won’t grow into something Partnis can use. He’ll sell you on.’ Regol raised a hand as Denam started to speak. ‘And not to a salt mine or to be used as the filling in a pie – just to any place that has a need you can meet.’ He lowered his hand. ‘Any questions?’

A cracking sound filled the immediate silence and it took Nona a moment to realize it was Denam’s knuckles as he formed fists. The giant’s scowl deepened. ‘I really hate you, Regol.’

‘Not a question. Anyone else?’

Silence.

Regol walked back into the darkness, stepping rafter to rafter with the unconscious grace of a cat.

Life in the Caltess proved to be a big improvement on an open cage rattling along the back-lanes of empire. Truth be told, it was an improvement on life in Nona’s village. Here she might be the smallest but she wasn’t the odd one out. The isolation of the village bred generations so similar in looks you might pick any handful at random to make a convincing family. Nona alone hadn’t fit the mould. A goat in the sheep herd. The family Partnis’s purse had furnished him with mixed every size and shape, every colour and shade, and in the attic’s gloom they were much of a muchness even so.

In addition to the four dozen children Partnis kept immediately beneath his roof, he housed a dozen apprentices, and seven fighters in their own set of rooms around the great hall. The apprentices shared a barracks house out in the rear of the compound.

Nona found a spot wedged between grain sacks larger than herself. Saida had more difficulty finding a space to squeeze into and was turned away by older residents time and again, even those she dwarfed. But in the end she settled on the boards close to Nona’s sack-pile, further back where the roof sloped so low that she had to roll into place.

That first night the hall opened its doors and the world flowed in to see men bleed. Denam and Regol got to watch from the highest rungs of the ladder in the furthest corner of the great hall, behind counters where the apprentices sold ale and wine to the crowd. The eldest of the remaining children crowded around the trapdoor. Everyone else had to find some chink among the rafters through which the events below might be glimpsed.

Nona’s spot afforded her a narrow view of the second ring. She wondered that they called it a ring when in fact the ropes strung between the four posts enclosed a square perhaps eight yards on a side, the whole thing a raised platform so that the fighter’s feet were level with the average man’s brow. She could see the tops of many heads, hundreds packed tight. The hubbub of their voices filled the attic. As the crowd built so did the noise, each of them having to shout just to be heard by their neighbour.

Saida lay close by, her eye to a crack. At her side an older boy, Marten, peered through a knot hole to which he laid ownership.

‘It’s all-comers tonight,’ Marten said, without looking up. ‘Ranking bouts on the seven-day, all comers on the second, exhibitions on the fourth. Blade matches are the last day of the month.’

‘My da said men fight in pits in the city …’ Saida said timidly, waiting to be told she was wrong.

‘In the Marn ports some do,’ Marten said. ‘Partnis says it’s a foolishness. If you’ve got willing fighters and a paying crowd you put them up on a platform, not down in a hole, where only the first row can see them.’

Nona lay, watching the throng below her while fights progressed unseen at the hall’s far end. Her view offered only the tops of heads, but she judged reactions by the pulse and flow of the crowd. Their roaring sounded at times like the howl of a single great beast, so loud it resonated in her chest, throbbing in her own voice when she yelled her challenge back at them.

At last a figure climbed into the ring beneath them. All around her Nona could feel other children scrambling for a view. Someone tried to lift her from her spot but she caught the hands that grabbed her and dug her nails in. The unknown someone dropped her with a howl and she put her eye back to the crack.

‘Raymel!’ The voices around her echoed the cries of the mob.

In the ring he looked a heavily-built man with thick blond hair, naked save for the white cloth bound around his groin, his skin gleaming with oil, the muscles of his stomach in sharp relief, showing each band divided from the next. Nona had glimpsed him wandering the hall earlier in the day and knew that he was enormous, taller even than Maya, and moving with none of her awkward blunder. Raymel prowled, a killer’s confidence in each motion. The man was a gerant prime. In the attic’s dimness Nona had learned the code that Partnis and Giljohn had used when selling her. The range ran from touch through half-blood and prime to full-blood. A touch could be thought of as quarter-blood and a prime as three-quarters. For gerants, primes often made the best fighters, full-bloods though rarer still and larger were too slow – though perhaps they just said that at the Caltess as they had none to show.

‘You’ll see something now!’ A girl’s voice, excited, at Nona’s left.

Marten had explained that any hopeful wishing to win a fight purse, or even to join the Caltess, could present themselves on all-comers’ night and for a crown they might pit themselves against Partnis’s stable.

‘Raymel will kill them,’ Saida said, awestruck.

‘He won’t.’ Even shouting above the roar Marten managed to sound scornful. ‘He’s paid to win. He’ll put on a show. Killing’s not good for business.’

‘Except when it is.’ Another voice close at hand.

‘Raymel does what he wants.’ The girl to Nona’s left. ‘He might kill someone.’ She sounded almost hungry for it.

A challenger entered the ring: a bald man, fat and powerful, the hair on his back so thick and black as to hide his skin. He had arms like slabs of meat – perhaps a smith given to swinging a hammer every day. Nona couldn’t see his face.

‘Doesn’t Partnis tell Raymel—’

‘No one tells Raymel.’ The girl cut Saida off. ‘He’s the only highborn to step into a ring in fifty years. Regol said so. You don’t tell the highborn what to do. The money’s nothing to him.’

Nona had heard the same tone of worship in the Hope church where her mother and Mari Streams called on the new god and sang the hymns Preacher Mickel taught them.