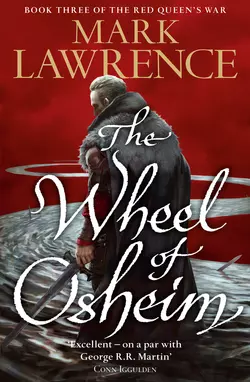

The Wheel of Osheim

Mark Lawrence

From the critically-acclaimed author of PRINCE OF FOOLS comes the third volume of the brilliant new epic fantasy series, THE RED QUEEN’S WAR.All the horrors of Hell stand between Snorri Ver Snagason and the rescue of his family, if indeed the dead can be rescued.For Jalan Kendeth getting back out alive and with Loki’s Key is all that matters. Loki’s creation can open any lock, any door, and it may also be the key to Jal’s fortune back in the living world.Jal plans to return to the three Ws that have been the core of his idle and debauched life: wine, women, and wagering. Fate however has other, larger, plans…The Wheel of Osheim is turning ever faster and it will crack the world unless it’s stopped. When the end of all things looms, and there’s nowhere to run, even the worst coward must find new answers.Jal and Snorri face many dangers – from the corpse-hordes of the Dead King to the many mirrors of the Lady Blue; but in the end, fast or slow, the Wheel of Osheim will exert its power.In the end it’s win or die.

Copyright (#u5e59e188-e654-55b1-b7af-f199ebb21e75)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2016

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover Illustration © Jason Chan

Map © Andrew Ashton

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007531639

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780008171001

Version: 2017-10-27

Praise for The Wheel of Osheim (#u5e59e188-e654-55b1-b7af-f199ebb21e75)

‘A triumphant conclusion … Jalan’s wry narration enhances Lawrence’s heady, enjoyable mix of court intrigue, dirty family politics, and ancient magic. Both new readers and series fans will enjoy this dark and lively epic fantasy’

Publishers Weekly

‘The Wheel of Osheim presents everything our followers could want in a fantasy book, which is no less than one would expect from Mark Lawrence’

Grimdark Magazine

‘Lawrence’s writing makes every page a pleasure to read … The Wheel of Osheim his most outstanding contribution to the genre … so far’

Fantasy-Faction.com

‘The best book I’ve read this year, maybe the best book I’ve read for a few years … I cannot recommend this trilogy highly enough’

FantasyBookReview.co.uk

Praise for The Liar’s Key (#u5e59e188-e654-55b1-b7af-f199ebb21e75)

‘Lawrence improves with every book he writes and if he keeps on like this, we may have to turn the ratings system up to eleven. Magnificent, and highly recommended’

Starburst Magazine

‘The dialogue is a humorous, frightening lullaby that flawlessly depicts this dark, disturbing universe and its meticulously constructed characters, both friends and fiends’

RT Book Reviews

‘Mark gives us a perfect second book that, just like Jalan, is far more faceted that most. I’m already looking forward to starting it again’

Fantasy-Faction.com

‘Mark Lawrence should be commended on another excellent book of The Red Queen’s War trilogy’

Impulse Gamer

Praise for Prince of Fools (#u5e59e188-e654-55b1-b7af-f199ebb21e75)

‘Mark Lawrence’s growing army of fans will relish this rollicking new adventure and look forward to the next one’

Daily Mail

‘A bit like The Wizard of Oz but with whores and gore’

Sun

‘Keeps us turning pages with a careful balance of quips and gory incident’

SFX

‘There are special rewards in store here for readers of The Broken Empire series. Highly recommended’

ROBIN HOBB, author of the internationally bestselling Realm of the Elderlings series

‘Mark Lawrence is the best thing to happen to fantasy in recent years’

PETER V. BRETT, internationally bestselling author of The Demon Cycle

‘A savage voice which is telling you a good jest while trying to drown you in story’

ROBERT LOW, author of The Kingdom Series and The Oathsworn Series

‘Really excellent, gritty fantasy – I’m trying to avoid comparison with A Game of Thrones, but I’m afraid it’s right there. But funnier. Very funny indeed’

ANTHONY MCGOWAN, author of The Knife That Killed Me

Praise for The Broken Empire trilogy (#ulink_5eb2812d-00f7-523e-b403-db9cfa1f3eea)

‘Excellent – on a par with George R.R. Martin’

CONN IGGULDEN

‘Like … Stephen Donaldson, Mark Lawrence gets the reader firmly behind the flawed saviour that he has created. Soaring fantasy’

Sun

‘Dark, disturbing and horribly gripping … [Prince of Thorns] is a dystopian thriller that strong-stomached readers … who love the TV series Game of Thrones will find right up their street’

The Times

‘[A] morbidly gripping, gritty fantasy tale’

Publishers Weekly

‘In recent years, a cohort of writers including Joe Abercrombie, Mark Lawrence and Brent Weeks has resurrected heroic fantasy and placed it firmly back in the bestseller lists’

Guardian

‘Dark and relentless, Prince of Thorns will pull you under and drown you in story. A two-in-the-morning page turner. Absolutely stunning … jaw-dropping’

ROBIN HOBB

‘A hard-edged tale of survival and conquest in a brutal medieval world, well told and very compelling’

TERRY BROOKS, internationally bestselling author of the Shannara books

‘Marks an unbroken and steady ascent to the top of my favourite-fantasy pile. Lawrence gets better with each book he writes’

MYKE COLE, author of the Shadow Ops series

‘Emperor of Thorns … is a mighty achievement that grew richer as it developed, and a brilliant twist at the very end brings this trilogy to a worthy and quite astounding conclusion’

Daily Mail

Dedication (#ulink_6bb1bd30-d260-57d5-9ea7-e68ed02bf379)

Dedicated to my father, Patrick.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u266b9791-b581-54a1-8670-a7c1bce88cd6)

Title Page (#u32ee0a2c-fce4-5b63-b54e-284340a61a5d)

Copyright (#u58ea2bea-0345-506c-8c9c-361661b65035)

Praise for The Wheel of Osheim (#u0c6c42ef-4f7b-5762-8509-afd44f5b88d4)

Praise for The Liar’s Key (#u242accb8-9523-566d-911a-444cde13c06b)

Praise for Prince of Fools (#uc5ebd4e1-ea20-5248-bf19-2d20026cb92c)

Praise for The Broken Empire Trilogy (#uac0866cc-25bd-54cd-86c6-682ec027f571)

Dedication (#u6856915a-dea5-5fc8-b31c-35d7fe4744df)

Map (#u70be9e01-6d4b-5dbf-a989-b442355271cd)

Author’s Note (#uac96a976-d222-594b-8b9a-f7fb8e9e0ed7)

Prologue (#ub5d16c31-d3ba-56b3-afff-0bbaca57f908)

Chapter 1 (#ua75d09c4-e2c8-59b5-9686-6fb0da52f725)

Chapter 2 (#u058b1d32-b6d6-5d9e-9f53-e3badb3a159c)

Chapter 3 (#ueb77d89c-1616-5cf0-8c08-bfa012187adf)

Chapter 4 (#ub80182bd-674c-5f0e-847b-95136f9494f6)

Chapter 5 (#u7285cc7c-b6c1-5546-a9b9-5ccad5486858)

Chapter 6 (#ub9fd2c5d-a762-54f7-8e4a-1b33146f9180)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mark Lawrence (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#ulink_8c87d8e6-cea6-5138-8524-088d66817dfc)

For those of you who have had to wait a year for this book I provide brief catch-up notes to Book 3, so that your memories may be refreshed and I can avoid the awkwardness of having to have characters tell each other things they already know for your benefit.

Here I carry forward only what is of importance to the tale that follows.

1. Jalan Kendeth, grandson to the Red Queen, has few ambitions. He wants to be back in his grandmother’s capital, rich, and out of danger. He’d also love to lord it over his older brothers Martus and Darin.

2. Life has become a little more complicated of late. Jalan still lusts after his former love, Lisa DeVeer, but she’s now married to his best friend. Additionally he’s still in massive debt to the murderous crime lord Maeres Allus, and wanted for fraud by the great banks of Florence. Plus, he’s vowed revenge on Edris Dean, the man who killed his mother and his sister. His sister was still in his mother’s womb and the necromantic sword Edris used (that Jalan now carries) trapped her in Hell, ready to return as an unborn to serve the Dead King. Jalan’s sister had the potential to be a powerful sorceress and will make a very dangerous unborn – such potent unborn require the death of a close family member to return to the living world.

3. Jalan has travelled from the frozen north to the burning hills of Florence. He began his trip with Norsemen Snorri and Tuttugu of the Undoreth, picking up a Norse witch named Kara, and Hennan, a young boy from Osheim, on the way.

4. Jalan and Snorri were bound to spirits of darkness and light respectively: Aslaug and Baraqel. During their journey those bonds were broken.

5. Jalan has Loki’s key, an artefact that can open any door. Many people want this – not least the Dead King who could use it to emerge from Hell.

6. In this book I use both Hell and Hel to describe the part of the afterlife into which our heroes venture. Hel is what the Norse call it. Hell is what it’s called in Christendom.

7. Tuttugu died in an Umbertide jail, tortured and killed by Edris Dean.

8. We last saw Jalan, Snorri, Kara and Hennan in the depths of the salt-mine where the door-mage, Kelem, dwelt.

9. Kelem was hauled off into the dark-world by Aslaug.

10. Snorri went through the door into Hel to save his family. Jalan said he would go with him, and gave Loki’s key to Kara so it wouldn’t fall into the Dead King’s hands. Jalan’s nerve failed him and he didn’t follow Snorri. He pickpocketed the key back off Kara and a moment later someone pushed the door open from the Hel side and hauled him through.

11. More generally: Jalan’s grandmother, Alica Kendeth, the Red Queen, has been fighting a hidden war with the Lady Blue and her allies for many years. The Lady Blue is the guiding hand behind the Dead King, and the necromancer Edris Dean is one of her agents.

12. Aiding the Red Queen are her twin older siblings, the Silent Sister – who sees the future but never speaks – and her disabled brother Garyus, who runs a commercial empire of his own.

13. The Red Queen’s War is about the change the Builders made in reality a thousand years previously – the change that introduced magic into the world shortly before the previous society (us in about fifty years) was destroyed in a nuclear war.

14. The change the Builders made has been accelerating as people use magic more – in turn allowing more magic to be used – a vicious cycle that is breaking down reality and leading to the end of all things.

15. The Red Queen believes the disaster can be averted – or that she should at least try. The Lady Blue wants to accelerate to the end, believing that she and a select few can survive to become gods in whatever will follow.

16. Dr Taproot appeared to be a circus master going about his business, but Jalan saw him in his grandmother’s memories of sixty years ago, acting as head of her grandfather’s security and much the same age as he is now…

17. The Wheel of Osheim is a region to the north where reality breaks down and every horror from a man’s imagination is given form. Kara’s studies indicate that at the heart of it was a great machine, a work of the Builders, mysterious engines hidden in a circular underground tunnel many miles across. Quite what role it plays in the disaster to come is unclear…

Prologue (#ulink_4eca3a54-74ef-5f9d-a913-cf4ae536faca)

In the deepness of the desert, amid dunes taller than any prayer tower, men are made tiny, less than ants. The sun burns there, the wind whispers, all is in motion, too slow for the eye but more certain than sight. The prophet said sand is neither kind nor cruel, but in the oven of the Sahar it is hard to think that it does not hate you.

Tahnoon’s back ached, his tongue scraped dry across the roof of his mouth. He rode, hunched, swaying with the gait of his camel, eyes squinting against the glare even behind the thin material of his shesh. He pushed the discomfort aside. His spine, his thirst, the soreness of the saddle, none of it mattered. The caravan behind him relied on Tahnoon’s eyes, only that. If Allah, thrice-blessed his name, would grant that he saw clearly then his purpose was served.

So Tahnoon rode, and he watched, and he beheld the multitude of sand and the vast emptiness of it, mile upon baking mile. Behind him, the caravan, snaking amid the depths of the dunes where the first shadows would gather come evening. Around its length his fellow Ha’tari rode the slopes, their vigilance turned outward, guarding the soft al’Effem with their tarnished faith. Only the Ha’tari kept to the commandments in spirit as well as word. In the desert such rigid observance was all that kept a man alive. Others might pass through and survive, but only Tahnoon’s people lived in the Sahar, never more than a dry well from death. Treading the fine line in all things. Pure. Allah’s chosen.

Tahnoon angled his camel up the slope. The al’Effem sometimes named their beasts. Another weakness of the tribes not born in the desert. In addition, they scrimped on the second and fourth prayers of each day, denying Allah his full due.

The wind picked up, hot and dry, making the sand hiss as it stripped it from the sculpted crest of the dune. Reaching the top of the slope, Tahnoon gazed down into yet another empty sun-hammered valley. He shook his head, thoughts returning along his trail to the caravan. He glanced back toward the curving shoulder of the next dune, behind which his charges laboured along the path he had set them. These particular al’Effem had been in his care for twenty days now. Two more and he would deliver them to the city. Two more days to endure until the sheikh and his family would grate upon him no longer with their decadent and godless ways. The daughters were the worst. Walking behind their father’s camels, they wore not the twelve-yard thobe of the Ha’tari but a nine-yard abomination that wrapped so tight its folds barely concealed the woman beneath.

The curve of the dune drew his eye and for a second he imagined a female hip. He shook the vision from his head and would have spat were his mouth not so dry.

‘God forgive me for my sin.’

Two more days. Two long days.

The wind shifted from complaint to howl without warning, almost taking Tahnoon from his saddle. His camel moaned her disapproval, trying to turn her head from the sting of the sand. Tahnoon did not turn his head. Just twenty yards before him and six foot above the dune the air shimmered as if in mirage, but like none Tahnoon had seen in forty dry years. The empty space rippled as if it were liquid silver, then tore, offering glimpses of some place beyond, some stone temple lit by a dead orange light that woke every ache the Ha’tari had been ignoring and turned each into a throbbing misery. Tahnoon’s lips drew back as if a sour taste had filled his mouth. He fought to control his steed, the animal sharing his fear.

‘What?’ A whisper to himself, lost beneath the camel’s complaints.

Revealed in ragged strips through rents in the fabric of the world Tahnoon saw a naked woman, her body sculpted from every desire a man could own, each curve underwritten with shadow and caressed by that same dead light. The woman’s fullness held Tahnoon’s eye for ten long heartbeats before his gaze finally wandered up to her face and the shock tumbled him from his perch. Even as he hit the ground he had his saif in hand. The demon had fixed its eyes upon him, red as blood, mouth gaping, baring fangs like those of a dozen giant cobras.

Tahnoon scrambled back to the top of the dune. His terrified steed was gone, the thud of her feet diminishing behind him as she fled. He gained the crest in time to see the slashed veil between him and the temple ripped wide, as if a raider had cut their way through the side of a tent. The succubus stood fully displayed and before her, now tumbling out of that place through the torn air, a man, half-naked. The man hit the sand hard, leapt up in an instant, and reached overhead to where the succubus made to pursue him, feeling her way into the rip that he’d dived through headfirst. As she reached for him, needle-like claws springing from her fingertips, the man jabbed upward, something black clutched in his fist, and with an audible click it was all gone. The hole torn into another world – gone. The demon with her scarlet eyes and perfect breasts – gone. The ancient temple vanished, the dead light of that awful place sealed away again behind whatever thinness keeps us from nightmare.

‘Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!’ The man started to hop from one bare foot to the other. ‘Hot! Hot! Hot!’ An infidel, tall, very white, with the golden hair of the distant north across the sea. ‘Fuck. Hot. Fuck. Hot.’ Pulling on a boot that must have spilled out with him, he fell, searing his bare back on the scalding sand and leaping to his feet again. ‘Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!’ The man managed to drag on his other boot before toppling once more and vanishing head over heels down the far side of the dune screaming obscenities.

Tahnoon stood slowly, sliding his saif back into its curved scabbard. The man’s curses diminished into the distance. Man? Or demon? It had escaped from hell, so demon. But its words had been in the tongue of the old empire, thick with the coarse accent of northmen, putting uncomfortable angles on every syllable.

The Ha’tari blinked and there, written in green on red across the back of his eyelids, the succubus stretched toward him. Blinked again, once, twice, three times. Her image remained, enticing and deadly. With a sigh Tahnoon started to trudge down after the yelping infidel, vowing to himself never to worry about the scandalous nine-yard thobes of the al’Effem again.

1 (#ulink_d6f37888-0ac6-5c85-9615-df44f26f7b03)

All I had to do was walk the length of the temple and not be seduced from the path. It would have taken two hundred paces, no more, and I could have left Hell by the judges’ gate and found myself wherever I damn well pleased. And it would have been the palace in Vermillion that I pleased to go to.

‘Shit.’ I levered myself up from the burning sand. The stuff coated my lips, filled my eyes with a thousand gritty little grains, even seemed to trickle out of my ears when I tilted my head. I squatted, spitting, squinting into the brilliance of the day. The sun scorched down with such unreasonable fierceness that I could almost feel my skin withering beneath it. ‘Crap.’

She had been gorgeous though. The part of my mind that had known it was a trap only now struggled out from under the more lustful nine tenths and began shouting ‘I told you so!’

‘Bollocks.’ I stood up. An enormous sand dune curved steeply up before me, taller than seemed reasonable and blazing hot. ‘A fucking desert. Great, just great.’

Actually, after the deadlands even a desert didn’t feel too bad. Certainly it was far too hot, eager to burn any flesh that touched sand, and likely to kill me within an hour if I didn’t find water, but all that aside, it was alive. Yes, there wasn’t any hint of life here, but the very fabric of the place wasn’t woven from malice and despair, the very ground didn’t suck life and joy and hope from you as blotting paper takes up ink.

I looked up at the incredible blueness of the sky. In truth a faded blue that looked to have been left out in the sun too long but after the unchanging dead-sky with its flat orange light all colours looked good to my eye: alive, vibrant, intense. I stretched out my arms. ‘Damn, but it’s good to be alive!’

‘Demon.’ A voice behind me.

I made a slow turn, keeping my arms wide, hands empty and open, the key thrust into the undone belt struggling to keep my trews up.

A black-robed tribesman stood there, curved sword levelled at me, the record of his passage down the dune written across the slope behind him. I couldn’t see his face behind those veils they wear but he didn’t seem pleased to see me.

‘As-salamu alaykum,’ I told him. That’s about all the heathen I picked up during my year in the desert city of Hamada. It’s the local version of ‘hello’.

‘You.’ He gestured sharply upward with his blade. ‘From sky!’

I turned my palms up and shrugged. What could I tell him? Besides any good lie would probably be wasted on the man if he understood the Empire tongue as poorly as he spoke it.

He eyed the length of me, his veil somehow not a barrier to the depth of his disapproval.

‘Ha’tari?’ I asked. In Hamada the locals relied on desert-born mercenaries to see them across the wastes. I was pretty sure they were called Ha’tari.

The man said nothing, only watched me, blade ready. Eventually he waved the sword up the slope he’d come down. ‘Go.’

I nodded and started trudging back along his tracks, grateful that he’d decided not to stick me then and there and leave me to bleed. The truth was of course he didn’t need his sword to kill me. Just leaving me behind would be a death sentence.

Sand dunes are far harder to climb than any hill twice the size. They suck your feet down, stealing the energy from each stride so you’re panting before you’ve climbed your own height. After ten steps I was thirsty, by halfway parched and dizzy. I kept my head down and laboured up the slope, trying not to think about the havoc the sun must be wreaking on my back.

I’d escaped the succubus by luck rather than judgment. I’d had to bury my judgment pretty deep to allow myself to be led off by her in any event. True, she’d been the first thing I’d seen in all the deadlands that looked alive – more than that, she’d been a dream in flesh, shaped to promise all a man could desire. Lisa DeVeer. A dirty trick. Even so, I could hardly have claimed not to have been warned, and when she pulled me down into her embrace and her smile split into something wider than a hyena’s grin and full of fangs I was only half-surprised.

Somehow I’d wriggled free, losing my shirt in the process, but she’d have been on me quick enough if I hadn’t seen the walls ripple and known that the veils were thin there, very thin indeed. The key had torn them open for me and I’d leapt through. I hadn’t known what would be waiting for me, nothing good to be sure, but likely it had fewer teeth than my new lady friend.

Snorri had told me the veils grew thinnest where the most people were dying. Wars, plagues, mass executions … anywhere that souls were being separated from flesh in great numbers and needed to pass into the deadlands. So finding myself in an empty desert where nobody was likely to die apart from me had been a bit of a surprise.

Each part of the world corresponds to some part of the deadlands – wherever disaster strikes, the barrier between the two places fades. They say that on the Day of a Thousand Suns so many died in so many places at the same time that the veil between life and death tore apart and has never properly repaired itself. Necromancers have exploited that weakness ever since.

‘There!’ The tribesman’s voice brought me back to myself and I found we’d reached the top of the dune. Following the line of his blade I saw down in the valley, between our crest and the next, the first dozen camels of what I hoped would be a large caravan.

‘Allah be praised!’ I gave the heathen my widest smile. After all, when in Rome…

More Ha’tari converged on us before we reached the caravan, all black-robed, one leading a lost camel. My captor, or saviour, mounted the beast as one of his fellows tossed him the reins. I got to slip and slide down the dune on foot.

By the time we reached the caravan the whole of its length had come into view, a hundred camels at least, most laden with goods, bales wrapped in cloth stacked high around the animals’ humps, large storage jars hanging two to each side, their conical bases reaching almost to the sand. A score or so of the camels bore riders, robed variously in white, pale blue or dark checks, and a dozen more heathens followed on foot, swaddled beneath mounds of black cloth, and presumably sweltering. A handful of scrawny sheep trailed at the rear, an extravagance given what it must have cost to keep them watered.

I stood, scorching beneath the sun, while two of the Ha’tari intercepted the trio of riders coming from the caravan. Another of their number disarmed me, taking both knife and sword. After a minute or two of gesticulating and death threats, or possibly reasoned discourse – the two tend to sound the same in the desert tongue – all five returned, a white-robe in the middle, a checked robe to each side, the Ha’tari flanking.

The three newcomers were bare-faced, baked dark by the sun, hook-nosed, eyes like black stones, related I guessed, perhaps a father and his sons.

‘Tahnoon tells me you’re a demon and that we should kill you in the old way to avert disaster.’ The father spoke, lips thin and cruel within a short white beard.

‘Prince Jalan Kendeth of Red March at your service!’ I bowed from the waist. Courtesy costs nothing, which makes it the ideal gift when you’re as cheap as I am. ‘And actually I’m an angel of salvation. You should take me with you.’ I tried my smile on him. It hadn’t been working recently but it was pretty much all I had.

‘A prince?’ The man smiled back. ‘Marvellous.’ Somehow one twist of his lips transformed him. The black stones of his eyes twinkled and became almost kindly. Even the boys to either side of him stopped scowling. ‘Come, you will dine with us!’ He clapped his hands and barked something at the elder son, his voice so vicious that I could believe he’d just ordered him to disembowel himself. The son rode off at speed. ‘I am Sheik Malik al’Hameed. My boys Jahmeen.’ He nodded to the son beside him. ‘And Mahood.’ He gestured after the departing man.

‘Delighted.’ I bowed again. ‘My father is…’

‘Tahnoon says you fell from the sky, pursued by a demon-whore!’ The sheik grinned at his son. ‘When a Ha’tari falls off his camel there’s always a demon or djinn at the bottom of it – a proud people. Very proud.’

I laughed with him, mostly in relief: I’d been about to declare myself the son of a cardinal. Perhaps I had sunstroke already.

Mahood returned with a camel for me. I can’t say I’m fond of the beasts but riding is perhaps my only real talent and I’d spent enough time lurching about on camelback to have mastered the basics. I stepped up into the saddle easy enough and nudged the creature after Sheik Malik as he led off. I took the words he muttered to his boys to be approval.

‘We’ll make camp.’ The sheik lifted up his arm as we joined the head of the column. He drew breath to shout the order.

‘Christ no!’ Panic made the words come out louder than intended. I pressed on, hoping the ‘Christ’ would slip past unnoticed. The key to changing a man’s mind is to do it before he’s announced his plan. ‘My lord al’Hameed, we need to ride hard. Something terrible is going to happen here, very soon!’ If the veils hadn’t thinned because of some ongoing slaughter it could only mean one thing. Something far worse was going to happen and the walls that divide life from death were coming down in anticipation…

The sheik swivelled toward me, eyes stone once more, his sons tensing as if I’d offered grave insult by interrupting.

‘My lord, your man Tahnoon had his story half right. I’m no demon, but I did fall from the sky. Something terrible will happen here very soon and we need to get as far away as we can. I swear by my honour this is true. Perhaps I was sent here to save you and you were sent here to save me. Certainly without each other neither of us would have survived.’

Sheik Malik narrowed his eyes at me, deep crows’ feet appearing, the sun leaving no place for age to hide. ‘The Ha’tari are a simple people, Prince Jalan, superstitious. My kingdom lies north and reaches the coast. I have studied at the Mathema and owe allegiance to no one in all of Liba save the caliph. Do not take me for a fool.’

The fear that had me by the balls tightened its grip. I’d seen death in all its horrific shades and escaped at great cost to get here. I didn’t want to find myself back in the deadlands within the hour, this time just another soul detached from its flesh and defenceless against the terrors that dwelt there. ‘Look at me, Lord al’Hameed.’ I spread my hands and glanced down across my reddening stomach. ‘We’re in the deep desert. I’ve spent less than a quarter of an hour here and my skin is burning. In another hour it will be blistered and peeling off. I have no robes, no camel, no water. How could I have got here? I swear to you, my lord, on the honour of my house, if we do not leave, right now, as fast as is possible, we will all die.’

The sheik looked at me as if taking me in for the first time. A long minute of silence passed, broken only by the faint hiss of sand and the snorting of camels. The men around us watched on, tensed for action. ‘Get the prince some robes, Mahood.’ He raised his arm again and barked an order. ‘We ride!’

The promised fleeing proved far more leisurely than I would have liked. The sheik discussed matters with the Ha’tari headman and we ambled up the slope of a dune, apparently on a course at right angles to their original one. The highlight of the first hour was my drink of water. An indescribable pleasure. Water is life and in the drylands of the dead I had started to feel more than half dead myself. Pouring that wonderful, wet, life into my mouth was a rebirth, probably as noisy and as much of a struggle as the first one given how many men it took to get the water-urn back off me.

Another hour passed. It took all the self-restraint I could muster not to dig my heels in and charge off into the distance. I had taken part in camel races during my time in Hamada. I wasn’t the best rider but I got good odds, being a foreigner. Being on a galloping camel bears several resemblances to energetic sex with an enormously strong and very ugly woman. Right now it was pretty much all I wanted, but the desert is about the marathon not the sprint. The heavily laden camels would be exhausted in half a mile, less if they had to carry the walkers, and whilst the sheik had been prodded into action by my story he clearly thought the chance I was a madman outweighed any advantage to be gained by leaving his goods behind for the dunes to claim.

‘Where are you heading, Lord al’Hameed?’ I rode beside him near the front of the column, preceded by his elder two sons. Three more of his heirs rode further back.

‘We were bound for Hamada and we will still get there, though this is not the direct path. I had intended to spend this evening at the Oasis of Palms and Angels. The tribes are gathering there, a meeting of sheiks before our delegations present themselves to the caliph. We reach agreement in the desert before entering the city. Ibn Fayed receives his vassals once a year and it is better to speak to the throne with one voice so that our requests may be heard more clearly.’

‘And are we still aiming for the oasis?’

The sheik snorted phlegm, a custom the locals seem to have learned from the camels. ‘Sometimes Allah sends us messages. Sometimes they’re written in the sand and you have to be quick to read them. Sometimes it’s in the flight of birds or the scatter of a lamb’s blood and you have to be clever to understand them. Sometimes an infidel drops on you in the desert and you’d have to be a fool not to listen to them.’ He glanced my way, lips pressed into a bitter line. ‘The oasis lies three miles west of the spot we found you. Hamada lies two days south.’

Many men would have chosen to take my warning to the oasis. I felt a moment of great relief that Malik al’Hameed was not one of them, or right now instead of riding directly away from whatever was coming I would be three miles from it, trying to convince a dozen sheiks to abandon their oasis.

‘And if they all die?’

‘Ibn Fayed will still hear a single voice.’ The sheik nudged his camel on. ‘Mine.’

A mile further on it occurred to me that although Hamada lay two days south, we were in fact heading east. I pulled up alongside the sheik again, displacing a son.

‘We’re no longer going to Hamada?’

‘Tahnoon tells me there is a river to the east that will carry us to safety.’

I turned in my saddle and gave the sheik a hard stare. ‘A river?’

He shrugged. ‘A place where time flows differently. The world is cracked, my friend.’ He held a hand up toward the sun. ‘Men fall from the sky. The dead are unquiet. And in the desert there are fractures where time runs away from you, or with you.’ A shrug. ‘The gap between us and whatever this danger of yours is will grow more quickly if we crawl this way than if we run in any other direction.’

I had heard of such things before, though never seen them. On the Bremmer Slopes in the Ost Reich there are bubbles of slo-time that can trap a man, releasing him after a week, a year, or a century, to a world grown older while he merely blinked. Elsewhere there are places where a man might grow ancient and find that in the rest of Christendom just a day has passed.

We rode on and perhaps we found this so-called river of time, but there was little to show for it. Our feet did not race, our strides didn’t devour seven yards at a time. All I can say is that evening arrived much more swiftly than expected and night fell like a stone.

I must have turned in my saddle a hundred times. If I had been Lot’s wife the pillar of salt would have stood on Sodom’s doorstep. I didn’t know what I was looking for, demons boiling black across the dunes, a plague of flesh-scarabs … I remembered the Red Vikings chasing us into Osheim what seemed a lifetime ago and half-expected them to crest a dune, axes raised. But, whatever fear painted there, the horizon remained stubbornly empty of threat. All I saw was the Ha’tari rear-guard, strengthened at the sheik’s request.

The sheik kept us moving deep into the night until at last the snorting of his beasts convinced him to call a halt. I sat back, sipping from a water skin, while the sheik’s people set up camp with practised economy. Great tents were unfolded from camelback, lines tethered to flat stakes long enough to find purchase in the sand, fires built from camel dung gathered and hoarded along the journey. Lamps were lit and set beneath the awnings of the tents’ porches, silver lamps for the sheik’s tent, burning rock-oil. Cauldrons were unpacked, storage jars opened, even a small iron oven set above its own oil burners. Spice scents filled the air, somehow more foreign even than the dunes and the strange stars above us.

‘They’re slaughtering the sheep.’ Mahood had come up behind me, making me jump. ‘Father brought them all this way to impress Sheik Kahleed and the others at the meet. Send ahead, I told him, get them brought out from Hamada. But no, he wanted to feast Kahleed on Hameed mutton, said he would know any deception. Desert-seasoned mutton is stringy, tough stuff, but it does have a flavour all its own.’ He watched the Ha’tari as he spoke. They patrolled on foot now, out on the moon-washed sands, calling to each other once in a while with soft melodic cries. ‘Father will want to ask you questions about where you came from and who gave you this message of doom, but that is a conversation for after the meal, you understand?’

‘I do.’ That at least gave me some time to concoct suitable lies. If I told the truth about where I had been and the things I had seen … well, it would turn their stomachs and they’d wish they hadn’t eaten.

Mahood and another of the sons sat down beside me and started to smoke, sharing a single long pipe, beautifully wrought in meerschaum, in which they appeared to be burning garbage, judging by the reek. I waved the thing away when they offered it to me. After half an hour I relaxed and lay back, listening to the distant Ha’tari and looking up at the dazzle of the stars. It doesn’t take long in Hell before your definition of ‘good company’ reduces to ‘not dead’. For the first time in an age I felt comfortable.

In time the crowd around the cooking pots thinned and a line of bearers carried the products of all that labour into the largest tent. A gong sounded and the brothers stood up around me. ‘Tomorrow we’ll see Hamada. Tonight we feast.’ Mahood, lean and morose, tapped his pipe out on the sand. ‘I missed many old friends at the oasis meet tonight, Prince Jalan. My brother Jahmeen was to meet his betrothed this evening. Though I feel he is rather pleased to delay that encounter, at least for a day or two. Let us hope for you that your warning proves to have substance, or my father will have lost face. Let us hope for our brothers on the sand that you are mistaken.’ With that he walked off and I trailed him to the glowing tent.

I pushed the flaps back as they swished closed behind Mahood, and stood, still half-bowed and momentarily blinded by the light of a score of cowled lanterns. A broad and sumptuous carpet of woven silks, brilliantly patterned in reds and greens, covered the sand, set with smaller rugs where one might expect the table and chairs to stand. Sheik al’Hameed’s family and retainers sat around a central rug crowded with silver platters, each heaped with food: aromatic rice in heaps of yellow, white, and green; dates and olives in bowls; marinated, dried, sweet strips of camel meat, dry roasted over open flame and dusted with the pollen of the desert rose; a dozen other dishes boasting culinary mysteries.

‘Sit, prince, sit!’ The sheik gestured to my spot.

I started as I registered for the first time that half of the company seated around the feast were women. Young beautiful women at that, clad in immodest amounts of silk. Impressive weights of gold crowded elegant wrists in glimmering bangles, and elaborate earrings descended in multi-petalled cascades to drape bare shoulders or collect in the hollows behind collarbones.

‘Sheik … I didn’t know you had…’ Daughters? Wives? I clamped my mouth shut on my ignorance and sat cross-legged where he indicated, trying not to rub elbows with the dark-haired visions to either side of me, each as tempting as the succubus and each potentially as lethal a trap.

‘You didn’t see my sisters walking behind us?’ One of the younger brothers whose name hadn’t stuck – clearly amused.

I opened my mouth. Those were women? They could have had four arms and horns under all that folded cloth and I’d have been no wiser. Sensibly I let no words escape my slack jaw.

‘We cover ourselves and walk to keep the Ha’tari satisfied,’ said the girl to my left, tall, lean, elegant, and perhaps no more than eighteen. ‘They are easily shocked, these desert men. If they came to the coast they might go blind for not knowing where to rest their eyes … poor things. Even Hamada would be too much for them.’

‘Fearless fighters, though,’ said the woman to my left, perhaps my age. ‘Without them, crossing the barrens would be a great ordeal. Even in the desert there are dangers.’

Across from us the other two sisters shared an observation, glancing my way. The older of the pair laughed, full-throated. I stared desperately at her kohl-darkened eyes, struggling to keep my gaze from dipping to the jiggle of full breasts beneath silk gauze strewn with sequins. I knew by reputation that Liban royalty, be it the ubiquitous princes, the rarer sheiks, or the singular caliph, all guarded their womenfolk with legendary zeal and would pursue vendettas across the centuries over as little as a covetous glance. What they might do over a despoiled maiden they left to the horrors of imagination.

I wondered if the sheik saw me as a marriage opportunity, having seated me amid his daughters. ‘I’m very grateful that the Ha’tari found me,’ I said, keeping my eyes firmly on the meal.

‘My daughters Lila, Mina, Tarelle, and Danelle.’ The sheik smiled indulgently as he pointed to each in turn.

‘Delightful.’ I imagined ways in which they might be delightful.

As if reading my mind the sheik raised his goblet. ‘We are not so strict in our faith as the Ha’tari but the laws we do keep are iron. You are a welcome guest, prince. But, unless you become betrothed to one of my daughters, lay no finger on them that you would rather keep.’

I reddened and started to bluster. ‘Sir! A prince of Red March would never—’

‘Lay more than a finger upon her and I will make her a gift of your testicles, gold-plated, to be worn as earrings.’ He smiled as if we’d been discussing the weather. ‘Time to eat!’

Food! At least there was the food. I would gorge to the point I was too full for even the smallest of lustful thoughts. And I’d enjoy it too. In the deadlands you starved. From the first moment you stepped into that deadlight until the moment you left it, you starved.

The sheik led us in their heathen prayers, spoken in the desert tongue. It took a damnable long time, my belly rumbling the while, mouth watering at the display set out before me. At last the lot of them joined in with a line or two and we were done. All heads turned to the tent flaps, expectant.

Two elderly male servants walked in with the main course on silver plates, square in the Araby style. Sitting on the floor I could just see a mound of food rising above the dishes, roast mutton no doubt, given the slaughtering earlier. God yes! My stomach growled like a lion, attracting nods of approval from Sheik Malik and his eldest son.

The server set my plate before me and moved on. A skinned sheep’s head stared at me, steaming gently, boiled eyes regarding me with an amused expression, or perhaps that was just the grin on its lipless mouth. A dark tongue coiled beneath a row of surprisingly even teeth.

‘Ah.’ I closed my own mouth with a click and looked to Tarelle on my left who had just received her own severed head.

She favoured me with a sweet smile. ‘Marvellous, is it not, Prince Jalan? A feast like this in the desert. A taste of home after so many hard miles.’

I’d heard that the Libans could get almost as stabby if you didn’t touch their food as they would if you did touch their women. I returned my gaze to the steaming head, its juices pooling around it, and considered how far I was from Hamada and how few yards I would get without water.

I reached for the nearest rice and started to heap my plate. Perhaps I could give the poor creature a decent burial and nobody would notice. Sadly I was the curiosity at this family feast and most eyes were turned my way. Even the dozen sheep seemed interested.

‘You’re hungry, my prince!’ Danelle to my right, her knee brushing mine each time she reached forward to add a date or olive to her plate.

‘Very,’ I said, grimly shovelling rice onto the monstrosity on my own. The thing had so little flesh that it was practically a grinning skull. The presence of a distinctly scooped spoon amid the flatware arranged by my plate suggested that a goodly amount of delving was expected. I wondered whether it was etiquette to use the same spoon for eyeballs as for brain…

‘Father says the Ha’tari think you fell from the sky.’ Lila from across the feast.

‘With a devil-woman giving chase!’ Mina giggled. The youngest of them, silenced by a sharp look from elder brother Mahood.

‘Well,’ I said. ‘I—’

Something moved beneath my rice heap.

‘Yes?’ Tarelle by my side, knee touching mine, naked beneath thin silks.

‘I certainly—’

Goddamn! There it was again, something writhing like a serpent beneath mud. ‘I … the sheik said your man fell from his camel.’

Mina was a slight thing, but unreasonably beautiful, perhaps not yet sixteen. ‘The Ha’tari are not ours. We are theirs now they have Father’s coin. Theirs until we are discharged into Hamada.’

‘But it’s true,’ Danelle, her voice seductively husky at my ear. ‘The Ha’tari would rather say the moon swung too low and knocked them from their steed than admit they fell.’

General laughter. The sheep’s purple tongue broke through my burial, coiling amid the fragrant yellow rice. I stabbed it with my fork, pinning it to the plate.

The sudden movement drew attention. ‘The tongue is my favourite,’ Mina said.

‘The brain is divine,’ Sheik al’Hameed declared from the head of the feast. ‘My girls puree it with dates, parsley and pepper then return it to the skull.’ He kissed his fingertips.

Whilst he held his children’s attention I quickly severed the tongue and with some frantic sawing reduced it to six or more sections.

‘Fine cooking skills are a great bonus in a wife, are they not, Prince Jalan? Even if she never has to cook it is well that she knows enough to instruct her staff.’ The sheik turned the focus back onto me.

‘Yes.’ I stirred the tongue pieces into the rice and heaped more atop them. ‘Absolutely.’

The sheik seemed pleased at that. ‘Let the poor man eat! The desert has given him an appetite.’

For a few minutes we ate in near silence, each traveller dedicated to their meal after weeks of poor fare. I worked at the rice around the edge of my burial, unwilling to put tainted mutton anywhere near my mouth. Beside me the delicious Tarelle inverted her own sheep’s head and started scooping out brains into her suddenly far less desirable mouth. The spoon made unpleasant scraping sounds along the inside of the skull.

I knew what had happened. Whilst in the deadlands Loki’s key had been invisible to the Dead King. Perhaps a jest of Loki’s, to have the thing become apparent only when out of reach. Whatever the reason, we had been able to travel the deadlands with less danger from the Dead King than we’d had during the previous year in the living world. Of course we had far more danger from every other damned thing, but that was a different matter. Now that the key was back among the living any dead thing could hunt it for the Dead King.

I was pretty sure Tarelle and Danelle’s sheep had turned their puffy eyeballs my way and I didn’t dare scrape away the rice from my own for fear of finding the thing staring back at me. I managed, by dint of continuously sampling from the dishes in the centre, to eat a vast amount of food whilst continuing to increase the mound on my own plate. After months in the deadlands it would take more than a severed head on my plate to kill my appetite. I drank at least a gallon from my goblet, constantly refilling it from a nearby ewer, only water sadly, but the deadlands had given me a thirst that required a small river to quench and the desert had only added to it.

‘This danger that you claim to have come to warn us of.’ Mahood pushed back his plate. ‘What is it?’ He rested both hands on his stomach. As lean as his father, he was taller, sharp featured, pockmarked, as quick to shift from friendly to sinister with just the slightest movement of his face.

‘Bad.’ I took the opportunity to push back my own plate. To be unable to clear your plate is a compliment to a Liban host’s largesse. Mine simply constituted a bigger compliment than usual, I hoped. ‘I don’t know what form it will take. I only pray that we are far enough away to be safe.’

‘And God sent an infidel to deliver this warning?’

‘A divine message is holy whatever it may be written upon.’ I had Bishop James to thank for that gem. He beat the words, if not the sentiment, into me after I decorated the privy wall with that bible passage about who was cleaving to whom. ‘And of course the messenger is never to be blamed! That one’s older than civilization.’ I breathed a sigh of relief as my plate was removed without comment.

‘And now dessert!’ The sheik clapped his hands. ‘A true desert dessert!’

I looked up expectantly as the servers returned with smaller square platters stacked along their arms, half expecting to be presented with a plate of sand. I would have preferred a plate of sand.

‘It’s a scorpion,’ I said.

‘A keen eye you have, Prince Jalan.’ Mahood favoured me with a dark stare over the top of his water goblet.

‘Crystallized scorpion, Prince Jalan! Can you have spent time in Liba and not yet tried one?’ The sheik looked confounded.

‘It’s a great delicacy.’ Tarelle’s knee bumped mine.

‘I’m sure I’ll love it.’ I forced the words past gritted teeth. Teeth that had no intention of parting to admit the thing. I stared at the scorpion, a monster fully nine inches long from the curve of the tail arching over its back to the oversized twin claws. The arachnid had a slightly translucent hue to it, its carapace orange and glistening with some kind of sugary glaze. Any larger and it could be mistaken for a lobster.

‘Eating the scorpion is a delicate art, Prince Jalan,’ the sheik said, demanding our attention. ‘First, do not be tempted to eat the sting. For the rest customs vary, but in my homeland we begin with the lower section of the pincer, like so.’ He took hold of the upper part and set his knife between the two halves. ‘A slight twist will crack—’

Out of the corner of my eye I saw the scorpion on my plate jitter toward me on stiff legs, six glazed feet scrabbling for purchase on the silver. I slammed my goblet down on the thing crushing its back, legs shattering, pieces flying in all directions, cloudy syrup leaking from its broken body.

All nine al’Hameeds stared at me in open-mouthed astonishment.

‘Ah … that’s…’ I groped for some kind of explanation. ‘That’s how we do it where I come from!’

A silence stretched, rapidly extending through awkward into uncomfortable, until with a deep belly-laugh Sheik Malik slammed his goblet down on his own scorpion. ‘Unsubtle, but effective. I like it!’ Two of his daughters and one son followed suit. Mahood and Jahmeen watched me with narrowed eyes as they started to dismember their dessert piece by piece in strict accordance with tradition.

I looked down at the syrupy mess of fragments in my own plate. Only the claws and stinger had survived. I still didn’t want to eat any of it. Opposite me, Mina popped a sticky chunk of broken scorpion into her pretty mouth, smiling all the while.

I picked up a piece, sharp-edged and dripping with ichor, hoping for some distraction so that I could palm the thing away. It was a pity the heathens took against dogs so. A hound at a feast is always handy for disposing of unwanted food. With a sigh I moved the fragment toward my lips…

When the distraction came I was almost too distracted to use the opportunity. One moment we sat illuminated by the fluttering light of a dozen oil lamps, the next the world outside lit up brighter than a desert noon, dazzling even through the tent walls. I could see the shadows of guy ropes stark against the material, the outline of a passing servant. The intensity of it grew from unbelievable to impossible, and outside the screaming started. A wave of heat reached me as if I had passed from shadow to sun. I barely had time to stand before the glow departed, as quickly as it came. The tent seemed suddenly dim. I stumbled over Tarelle, unable to make out my surroundings.

We exited in disordered confusion, to stare at the vast column of fire rising in the distance. A column of fire so huge it rose into the heavens before flattening against the roof of the sky and turning down upon itself in a roiling mushroom-shaped cloud of flame.

For the longest time we watched in silence, ignoring the screams of the servants clutching their faces, the panic of the animals, and the fried smell rising from the tents, which seemed to have been on the point of bursting into flame.

Even in the chaos I had time to reflect that things seemed to be turning out rather well. Not only had I escaped the deadlands and returned to life, I had now very clearly saved the life of a rich man and his beautiful daughters. Who knew how large my reward might be, or how pretty!

A distant rumbling underwrote the screams of men and animals.

‘Allah!’ Sheik Malik stood beside me, reaching only my shoulder. He had seemed taller on his camel.

That old Jalan luck was kicking in. Everything turning up roses.

‘It’s where we found him,’ Mahood said.

The rumbling became a roar. I had to raise my voice, nodding, and trying to look grim. ‘You were wise to listen to me, Sheik Mal—’

Jahmeen cut across me. ‘It can’t be. That was twenty miles back. No fire could be seen at such—’

The dunes before us exploded, the most distant first, then the next, the next, the next, quick as a man can beat a drum. Then the world rose around us and everything was flying tents and sand and darkness.

2 (#ulink_04eb197e-cb05-59c4-b22d-227415f29d9c)

I could have lost consciousness only for a moment for I gained my senses in time to see a dozen or more camels charging right at me, maddened by terror, eyes rolling. I lurched to my feet, spitting sand, and dived to one side. If I’d had a split second to think about my move I would have gone the other way. As it was, almost immediately I slammed into someone still staggering about while the rumbles of the explosion died away. Both of us followed my planned arc but fell short of the point I would have reached unimpeded. I did my level best to haul my screaming companion out from underneath me to use as a shield but just ended up with two handfuls of gauze and a camel’s foot stamping on my arse as it thundered by.

Groaning and clutching my rear, I rolled to the side, discovering that I appeared to have stripped and possibly killed one of the sheik’s daughters. The moonlight hid few details but with her hair in disarray I couldn’t tell which of the four it was. Figures closed on me from both sides, the sand settling out of the night as they came. Somewhere someone kept shrieking but the sound came muffled as if the loudness of detonation had reduced all other noise to insignificance.

The sheik’s elder sons pulled me to my feet, keeping an iron grip on my arms even after I’d stood up. A grey-haired retainer, bleeding from the nose and with the left side of his face blistered, covered the dead daughter with his tunic, leaving himself naked from the waist up, hollow-chested and wattled with the hanging skin old men wear. The sons were shouting questions or accusations at me but none of them quite penetrated the ringing in my ears.

The sand cleared from the air within a minute or so and the moon washed across the ruin of our camp. I stood, half-dazed, with Jahmeen’s knife to my throat, while Mahood shouted accusations at me, mostly about his sister, as if the destruction of the camp were as nothing compared to the baring of two breasts. However fine. Oddly I didn’t feel scared. The blast had left me somehow separated, as if I floated outside myself, an unconcerned observer, watching the surroundings as much as I watched Mahood’s raging or Jahmeen’s hand around the hilt of the blade at my neck.

It looked as if a hurricane had blown through leaving no tent standing. Those of us who had been inside when the night lit up were largely unharmed. Those who had been outside showed burns on any exposed flesh facing the direction of the explosion. The Ha’tari on patrol had fared better, though one looked to be blind. But the tribesmen who had been sitting around their prayer pole, unveiled in the darkness, had been burned as badly as the servants.

The camels had taken off but many of the caravaneers had gathered around the base of the nearest dune where the wounded were being treated, leaving me with the two brothers and three retainers out on more exposed sands. It was damnable cold in the desert night and I found myself shivering. The brothers might have thought it from fear, and Jahmeen grinned nastily at me, but some cataclysms are so terrifying that my habitual terror just ups and runs, and right now my fear was still lost somewhere out there in the night.

It wasn’t until Sheik Malik approached from the dunes with two Ha’tari, leading half a dozen camels, that I suddenly settled back into myself and started to panic, recalling his light-hearted talk of gold-plating the balls of any man who laid hands on his daughters.

‘I never touched her! I swear it!’

‘Touched who?’ The sheik left the camels to the Ha’tari and strode into the middle of the small gathering around me.

Jahmeen lowered the knife and the two brothers hauled me around to face their father. Behind him the column of fire continued to boil up into the night, yellow, orange, mottled with darkness, spreading out across the sky, huge despite the fact it would take a whole day to walk back to where it stood.

‘This was a Builders’ Sun.’ The sheik waved at the fire behind him.

My mind hadn’t even wandered into why or what yet but as the sheik said it I knew that he was right. The night had lit brighter than day. Had we been a few miles closer the tents would have burst into flame, the people outside turned into burning pillars. Who but the ancients had such power? I tried to imagine the Day of a Thousand Suns when the Builders scorched the world and broke death.

‘The infidel has despoiled Tarelle!’ Mahood shouted pointing at the figure sprawled beneath the robes.

‘And killed her!’ Jahmeen, waving his knife as if to make up for the fact that this was an afterthought.

The sheik’s face turned wooden. He dropped to the girl’s side and drew back the robe to expose her head. Tarelle chose that moment to sneeze and opened her eyes to fix her father with an unfocused stare.

‘My child!’ Sheik Malik drew his daughter to him, exposing enough neck and shoulder to give a Ha’tari apoplexy. He fixed me with cold eyes.

‘The camels!’ Tarelle pulled at her father’s arm. ‘They … he saved me, Father! Prince Jalan … he jumped into their path as they charged and carried me clear.’

‘It’s true!’ I lied. ‘I covered her with my body to save her from being crushed.’ I shook off the brothers’ hands with a snarl. ‘I got stepped on by the camel that would have trampled your daughter.’ In full bluster mode now I straightened out my robes, wishing they were a cavalry shirt and jacket. ‘And I don’t appreciate having a damned knife held to my throat by the brothers of the woman I protected at great personal risk. Brothers, it must be said, who would currently be on fire at the Oasis of Palms and Angels if I hadn’t been sent to save all your lives!’

‘Unhand him!’ The sheik shot dark looks at both sons, neither of which actually had hands on me any more, and waved them further back. ‘Go with Tahnoon and recover our animals! And you!’ He rounded on the three retainers, ignoring their injuries. ‘Get this camp back into order!’

Returning his attention to me, the sheik bowed at the waist. ‘A thousand pardons, Prince Jalan. If you would do me the honour of guarding my daughters while I salvage our trade goods I would stand in your debt!’

‘The honour is all mine, Sheik Malik.’ And I returned the bow, allowing my own to hide the grin I couldn’t keep from my face.

An hour later I found myself outside the sheik’s second best tent guarding all four of his daughters who huddled inside, wrapped once more in the ridiculous acreage of their thobes. The girls had three ageing maidservants to attend their needs and guard their virtue, but the trio hadn’t fared too well when the Builders’ Sun lit the night. Two had burns and the third looked to have broken a leg when the blast threw us all around. They were being tended a short distance off, outside the tent sheltering the injured men.

The important thing about the injured was that none of them looked mortally injured. The sands are staggeringly empty: the Dead King might have turned his eyes my way, but without corpses to work with he posed little threat.

I heard my name mentioned more than once as the sisters discussed the calamity in low voices behind me, Tarelle sharing the story of my bravery in the face of stampeding camels, and Lila reminding her sisters that my warning had saved them all. If I hadn’t been stuck outside in tribesman robes that stank of camel and itched my sunburn into a misery I might have felt quite pleased with myself.

The sheik, together with his sons and guards, had gone out amid the dunes to hunt down his precious cargo and the beasts it was tied onto. I couldn’t imagine how they could track the camels in the night, or how they hoped to find their way back to us either with or without them, but that seemed to be firmly the sheik’s problem and not mine.

I stood, leaning into the wind, eyes slitted against the fine grit it bore. During the whole day’s journey a light breeze had blown in across us from the west, but now the wind had turned toward the explosion, as if answering a summons, and strengthened into something that might easily become a sandstorm. The fire in the south had gone, leaving only darkness and questions.

After half an hour I gave up standing guard and started to sit guard instead, hollowing the sand to make it more comfortable for my bruised arse. I watched the sheik’s more able-bodied retainers salvaging additional tents and putting them back up as best they could. And I listened to the daughters, occasionally twirling a length of broken tent pole I’d picked up in lieu of a sword. I even started humming: it takes more than a Builders’ Sun exploding to take the gloss off a man’s first night in the living world after what seemed an eternity in Hell. I’d made it through the first two verses of The Charge of the Iron Lance when an unexplained stillness made me sit up straight and look around. Straining through the gloom I could make out the nearest of the men, standing motionless around a half-erected tent. I wondered why they’d stopped work. The real question struck me a few moments later. Why could I barely see them? It had become darker – much darker – and all within the space of a few minutes. I looked up. No stars. No moon. Which had to mean cloud. And that simply didn’t happen in the Sahar. Certainly not during the year I’d spent in Hamada.

The first drop of rain hit me square between the eyes. The second hit me in the right eye. The third hit the back of my throat as I made to complain. Within the space of ten heartbeats three drops had grown into a deluge that had me backing into the tent awning for shelter. Slim hands reached out for my shoulders and drew me in through the flaps.

‘Rain!’ Tarelle, her face in shadow, the light of a single lamp hinting at the curve of her cheekbone, her brow, the line of her nose.

‘How can it be raining?’ Mina, fearful yet excited.

‘I…’ I didn’t know. ‘The Builders’ Sun must have done it.’ Could a fire make it rain? A fire that big might change the weather … certainly the flames reached high enough to lick the very roof of the sky.

‘I heard that after the Day of a Thousand Suns there was a hundred years of winter. The winter of the north where water turns to stone and falls from the sky in flakes,’ Danelle said, her face at my shoulder, voice rich and commanding thrills down my spine.

‘I’m scared.’ Lila pressed closer as the rain began to hammer on the tent roof above us. I doubted we’d be dry for long – tents in Liba are intended to keep out the sun and the wind: they rarely have to contend with the wet.

A crack of thunder broke ridiculously close and suddenly Prince Jal was the filling in a four-girl sandwich. The boom paralysed me with terror for a moment and left my ears ringing, so it took me a short while to appreciate my position. Not even thirty-six yards of thobe could entirely disguise the sisters’ charms at this proximity. Moments later, though, a new fear surfaced to chase off any thoughts of taking advantage.

‘Your father made some very specific threats, ladies, concerning your virtue and I really—’

‘Oh, you don’t want to worry about that.’ A husky voice close enough to my ear to make me shiver.

‘Father says all manner of things.’ Softly spoken by a girl with her head against my chest. ‘And nobody will move until the rain stops.’

‘I can’t remember a time when we weren’t being watched over by Father, or our brothers, or his men.’ Another pressed soft against my shoulder.

‘And we do so need protecting…’ Behind me. Mina? Danelle? Whoever it was her hands were moving over my hips in a most unvirtuous way.

‘But the sheik—’

‘Gold plating?’ A tinkling laugh as the fourth sister started to push me down. ‘Did you really believe that?’

At least two of the girls were busy unwinding their thobes with swift and practised hands. Amid the shadows thrown by so many bodies I could see very little, but what I could see I liked. A lot.

All four of them pushed me down now, a tangled mass of smooth limbs and long hair, hands roaming.

‘Gold’s so expensive.’ Tarelle, climbing atop me, still half-wrapped.

‘That would be silly.’ Danelle, pressed to my side, deliciously soft, her tongue doing wonderful things to my ear. ‘He always uses silver…’

I tried to get up at that point, but there were too many of them, and things had got out of hand – except for the things that were now in hands … and, dammit, I’d been in Hell long enough, it was time for a spot of paradise.

There’s a saying in Liba: The last yard of the thobe is the best.

…or if there isn’t, there should be!

‘Arrrrgh!’

I’ve found that there are few things more effective at making a man’s ardour grow softer than cold water. When the tent roof, weakened by earlier traumas, gave without warning and released several gallons of icy rainwater over my back I jumped up sharply, scattering al’Hameed women and no doubt teaching them a whole new set of foreign curse words.

One thing that became clear as the water dripped off me was that very little more was dripping in to replace it.

‘Sshhh!’ I raised my voice over the last of their shrieking – they’d enjoyed the soaking no more than I had. ‘It’s stopped raining!’

‘عشيقة، هل أنت خخير؟’ A man just outside the tent, jabbering away in the heathen tongue, others joining him. They must have heard the screams. How much longer the fear of what the sheik would do to them if they burst in on his daughters would outweigh the fear of what the sheik would do to them if they failed to protect his daughters, I couldn’t say.

‘Cover yourselves!’ I shouted, moving to defend the entrance.

I heard smirking behind me, but they moved, presumably not expecting to emerge unscathed if reports of ‘frolicking’ reached their father.

Outside someone took hold of the tent flap. I’d not even laced it! With a yelp I flung myself down to grab the bottom of it. ‘Hurry for Christ’s sake! And blow out the lamp!’

That set them giggling again. I grabbed the lamp and pre-empted any attempt at entry by bursting out, setting the foremost of the sheik’s retainers on his backside in the wet sand.

‘They’re all fine!’ I straightened up and waved an arm back toward the tent. ‘The roof gave way under the rain … water everywhere.’ I did my best to mime the last part in case none of them had the Empire tongue. I don’t think the idiots got it because they stood there staring at me as if I’d asked a riddle. I strode purposefully away from the tent, beckoning the three men with me. ‘Look! It’ll all be clearer over here.’ I sincerely hoped those thobes went back on as quickly as they came off. Two of the sheik’s men were bringing over one of the sisters’ maids, urging her on despite her injuries.

‘What’s that over there?’ I said it mainly to distract everyone. As I looked in the direction I was pointing though … there was something. ‘Over there!’ I gesticulated more fiercely. Moonlight had started to pierce the shredding clouds overhead and something seemed to be emerging from the dune that I’d selected at random. Not cresting it, or stepping from its shadow, but struggling through the damp crust of sand.

Others started to see it now, their voices rising in confusion. From the broken sand something rose, a figure, impossibly slim, bone-pale.

‘Damn it all…’ I’d escaped from Hell and now Hell seemed to be following me. The dune had disgorged a skeleton, the bones connected by nothing but memory of their previous association. Another skeleton seemed to be fighting its way from the damp sand beside the first, constructing itself from assorted pieces as it came.

All around me people started to cry out in alarm, cursing, calling on Allah, or just plain screaming. They began to fall back. I retreated with them. Not long ago the sight would have had me sprinting in the direction that best carried me away from the two horrors before us, but I’d seen my share of dead, both in and out of Hell, and I kept the panic to just below boiling point.

‘Where did they come from? What are the odds we camped right where a couple of travellers died?’ It hardly seemed fair.

‘More than a couple.’ A timid voice behind me. I spun around to see four bethobed figures outside the women’s tent. ‘Over there!’ The speaker, the shortest so probably Mina, the youngest, pointed to my left. The sand in the lee of the dune had begun to heave and bony hands had emerged like a nightmare crop of weeds.

‘There was a city here once.’ The tallest … Danelle? ‘The desert ate it two hundred years ago. The desert has covered many such.’ She sounded calm: probably in shock.

The sheik’s retainers began to back in a new direction, retreating from both threats. The original two skeletons now seemed to sight us with their empty sockets and came on at a flat run, silent, their pace deadly, slowed only by the softness of the sand. That brought my panic to the boil. Before I could take to my heels though, a lone Ha’tari sprinted past me, having come through the camp. The sheik must have left one to patrol out among the dunes.

‘No sword!’ I held my empty hands up in excuse and let my retreat bring me among the four daughters. We stood together and watched the Ha’tari intercept the first of the skeletons. He hacked at its neck with his curved blade. Hearteningly, bone shattered beneath the blow, the skull flew clear and the rest of the skeleton collided with him, bouncing off to fall in a disarticulated heap on the sand.

The second skeleton rushed the warrior and he ran it through.

‘Idiot!’ I shouted, perhaps unreasonably because he’d acted on instinct and his reflexes were well honed.

Unfortunately sticking your blade through the chest of a skeleton is less of an inconvenience to the thing than it would have been back in the days when its bones were covered in flesh and guarded a lung. The skeleton ran into the thrust and clawed at the warrior’s face with bone fingers. The man fell back yelling, leaving his sword trapped between its ribs.

I saw now, as the last tatters of cloud departed and the moon washed across the scene, that the skeleton was not as unconnected as I had thought. The silver light illuminated a grey misty substance that wrapped each bone and linked it, albeit insubstantially, to the next, as if the phantom of their previous owner still hung about the bones and sought to keep them united. Where the first attacker had collapsed and scattered, the mist, or smoke, had stained the ground, and as the stain sank away the desert floor writhed, nightmare faces appearing in the sand, mouths opening in silent screams before they lost form and collapsed in turn.

The Ha’tari warrior continued to back away, bent double, both hands clutching his face. The skeleton rotated its skull toward us and started to run again, the sword trapped in its ribcage clattering as it came on.

‘This way!’ I turned to do some running of my own, only to see that skeletons were closing on the camp from all directions, gleaming white in the moonlight. ‘Hell!’

The sheik’s men had nothing better than daggers to defend themselves with, and I hadn’t even filched a knife from the evening meal.

‘There!’ Danelle caught my shoulder and pointed at the closest of several lamp stands that had been set between the tents, each a shaft of mahogany a good six foot tall and standing on a splayed base, the brass lamp cradled at the top.

‘That’s no damn use!’ I grabbed it anyway, letting the lamp fall and hefting the stand up with a grunt.

With nowhere to run I waited for the first of our attackers and timed my swing to its arrival. The lamp stand smashed through the skeleton’s ribcage, shattering it like matchwood and breaking its spinal column into a shower of loose vertebrae. The dead thing fell into a hundred pieces, and the phantom that had wrapped them sank slowly toward the fragments, a grey mist descending.

The momentum of my swing turned me right around and the daughters had to be quick on their feet to avoid being hit. I found myself with my back to my original foe and facing two more with no time to swing again. I jabbed the stand’s base into the breastbone of the foremost skeleton. Lacking flesh, the thing had little weight and the impact halted its charge, breaking bones and lifting it from its feet. The next skeleton reached me a moment later but I was able to smash the shaft of the stand into its neck like a quarterstaff then carry it down to the sand where my weight parted its skull from its body before its bony claws could reach me.

This left me on all fours amid the ruin of my last enemy but with half a dozen more racing my way, the closest just a few yards off. Still more were tearing into the sheik’s people, both the injured and the healthy.

I got to my knees, empty handed, and found myself facing a skeleton just about to dive onto me. The scream hadn’t managed to leave my mouth when a curved sword flashed above my head, shattering the skull about to hit my face. The rest of the horror bounced off me, falling into pieces, leaving a cold grey mist hanging in the air. I stepped up sharpish, shaking my hands as the phantom tried to leach into me through my skin.

‘Here!’ Tarelle had swung the sword and now pressed it into my grip. The Ha’tari’s blade – she must have recovered it from the remains of the first skeleton I put down.

‘Shit!’ I sidestepped the next attacker and took the head off the one behind.

Five or six more were charging in a tight knot. I briefly weighed surrender in the balance against digging a hole. Neither offered much hope. Before I had time to consider any other options a huge shape barrelled through the undead, bones shattering with brittle retorts. A Ha’tari on camelback brushed past me, swinging his saif, more following in his wake.

Within moments the sheik and his sons were dismounting around us, shouting orders and waving swords.

‘Leave the tents!’ Sheik Malik yelled. ‘This way!’ And he pointed up along the valley snaking between the dune crests that bracketed us.

Before long a column of men and women were limping their way behind the mounted sheik, flanked by his sons and his own armed tribesmen while the Ha’tari fought a rear-guard action against the bone hordes still being vomited forth from the damp sand.

A half mile on and we joined the rest of the sheik’s riders, standing guard around the laden camels they’d recovered from the surrounding desert.

‘We’ll press on through the night.’ The sheik stood in his stirrups atop his ghost-white camel to address us. ‘No stopping. Any who fall behind will be left.’

I looked over at Jahmeen, watching his father with strained intensity.

‘The Ha’tari will deal with the dead, won’t they?’ I couldn’t see mounted warriors being in too much danger from damp skeletons.

Jahmeen glanced my way. ‘When the bones rest uneasy it means the djinn are coming – from the empty places.’

‘Djinn?’ Stories of magic lamps, jolly fellows in silk pantaloons, and the granting of three wishes sprung to mind. ‘Are they really as bad as the dead trying to eat us?’

‘Worse.’ Jahmeen looked away, seeming less an angry young man and more a scared boy. ‘Much, much worse.’

3 (#ulink_5ee22b2b-4675-5e59-b339-509cba9aa64d)

‘So, about these djinn…’ We’d travelled no more than two miles and somehow it was daytime among the dunes, scorching hot, blinding, miserable as always. As we left the time-river rather than hasten into the next day we seemed to slip back into the one we’d escaped. The sun actually rose in the west in a reversal of the sunset we’d witnessed many hours before. The feeling was decidedly unsettling, and given my recent experiences ‘unsettling’ is no gentle word! ‘Tell me more.’ I didn’t really want to know any more about the djinn, but if the Dead King was sending more servants after the key I should at least know what I was running away from.

‘Creatures of invisible scorching fire,’ Mahood said on my right.