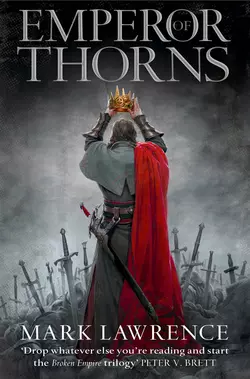

Emperor of Thorns

Mark Lawrence

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Историческое фэнтези

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 728.57 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Lawrence brings the Broken Empire series to its devastating conclusionThe path to the throne is broken – only the broken can walk itThe world is cracked and time has run through, leaving us clutching at the end days. These are the days that have waited for us all our lives. These are my days. I will stand before the Hundred and they will listen. I will take the throne no matter who stands against me, living or dead, and if I must be the last emperor then I will make of it such an ending.This is where the wise man turns away. This is where the holy kneel and call on God. These are the last miles, my brothers. Don′t look to me to save you. Run if you have the wit. Pray if you have the soul. Stand your ground if courage is yours. But don′t follow me.Follow me, and I will break your heart.