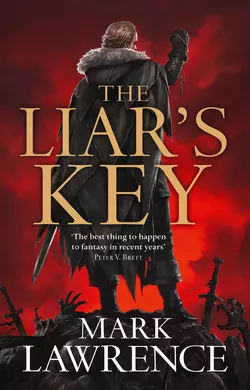

The Liar’s Key

Mark Lawrence

From the critically-acclaimed author of PRINCE OF FOOLS comes the second volume of the brilliant new epic fantasy series, THE RED QUEEN’S WAR.'If you like dark you will love Mark Lawrence. And when the light breaks through and it all makes sense, the contrast is gorgeous' ROBIN HOBBThe Red Queen has set her players on the board…Winter is keeping Prince Jalan Kendeth far from the luxuries of his southern palace. And although the North may be home to his companion, the warrior Snorri ver Snagason, he is just as eager to leave.For the Viking is ready to challenge all of Hel to bring his wife and children back into the living world. He has Loki’s key – now all he needs is to find the door.As all wait for the ice to unlock its jaws, the Dead King plots to claim what was so nearly his – the key into the world – so that the dead can rise and rule.

Copyright (#uf0366c84-6498-5aa2-8c73-dab2f7c02570)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2015

Jacket layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Jacket illustration © Jason Chan

Map © Andrew Ashton

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007531578

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780007531592

Version: 2017-10-23

Dedication (#uf0366c84-6498-5aa2-8c73-dab2f7c02570)

Dedicated to my mother, Hazel.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u520f1b44-1b91-5469-a2de-770610473d6f)

Title Page (#u3b8f8684-4f56-5c82-b8b4-1b6162227a39)

Copyright (#u46644c5d-92ec-5f07-9f79-00ec76941dc6)

Dedication (#ua37794d3-0902-5f7d-aeb0-42e043ccd925)

Author’s Note (#u193bfac2-c901-58ac-98ef-9577e1115595)

Map (#u2c1a7161-7e77-587a-889f-12e6314eb762)

Prologue (#ub0d33b49-1800-584a-b326-0b9726b6d0a1)

Chapter 1 (#ue8e32d09-ae1c-56ca-ad45-f6caaf28f57a)

Chapter 2 (#u2bd3f4c6-c244-547e-ba9f-9b903c2e9320)

Chapter 3 (#u704102ff-0f26-59f2-91f1-c68fa41f1fbe)

Chapter 4 (#u7aa18a97-8fb5-57ee-b2cb-99114b056336)

Chapter 5 (#uf0707461-9ae9-5447-8876-d1054380ce6f)

Chapter 6 (#ubb0d5e42-23bf-5376-a516-f9f70d07cecd)

Chapter 7 (#u956a428b-f12c-5043-afa4-4fdb88669f4a)

Chapter 8 (#ufc006624-e076-5f59-93a8-0ba165d36a91)

Chapter 9 (#ue76d9258-af5e-5004-b1c8-4563fade6477)

Chapter 10 (#u833260a3-fb30-50c6-9872-cbfc367df190)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mark Lawrence (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#uf0366c84-6498-5aa2-8c73-dab2f7c02570)

For those of you who have had to wait a year for this book I provide a brief note to Book 1, Prince of Fools, so that your memories may be refreshed and I can avoid the exquisite pain of having to have characters tell each other things they already know for your benefit.

Here I carry forward only what is of importance to the tale that follows.

1 1. Jalan Kendeth (grandson of the Red Queen) and Snorri ver Snagason (a very large Viking) set off from Red March (northern Italy) for the Bitter Ice (northern Norway), bound together by a spell that cursed one of them to be light-sworn and the other dark-sworn.

2 2. Jalan is now dark-sworn and visited each sunset by a female spirit called Aslaug.

3 3. Snorri is light-sworn and visited each sunrise by a male spirit called Baraqel.

4 4. They travelled to the Black Fort to rescue Snorri’s wife and surviving child from Sven Broke-Oar and agents of the Dead King, including necromancers, unborn, and Edris Dean. This rescue failed. Snorri’s family did not survive.

5 5. Jalan, Snorri and Tuttugu, a fat and slightly timid Viking, are the three survivors of the quest to the Black Fort. They have returned to the port town of Trond and spent the winter there.

6 6. Snorri has Loki’s key, a magical key that will open any lock. The Dead King wants this key very much.

7 7. Of their enemy at the Black Fort it is possible that Edris Dean and a number of the Hardassa (Red Vikings) survived, along with a handful of necromancers from the Drowned Isles.

8 8. Jalan’s grandmother, the Red Queen, remains in Red March with her elder sister, known as the Silent Sister, and her misshapen elder brother, Garyus. It was the Silent Sister’s spell that bound Snorri and Jalan together.

9 9. A number of powerful individuals use magic to manipulate events in the Broken Empire, often standing as the controlling interests behind many of the hundred thrones. The Dead King, the Lady Blue, the ice witch, Skilfar, and the dream-mage Sageous, are four such individuals. Jalan met Skilfar and Sageous on the way to the Black Fort. The Dead King has attempted to kill Jalan and Snorri several times. The Lady Blue is engaged in some long and secret war against the Red Queen and appears to be guiding the Dead King’s hand, though perhaps he doesn’t know it.

Prologue (#uf0366c84-6498-5aa2-8c73-dab2f7c02570)

Two men in a room of many doors. One tall in his robes, stern, marked with cruelty and intelligence, the other shorter, very lean, his hair a shock of surprise, his garb a changing motley confusing the eye.

The short man laughs, a many-angled sound as likely to kill birds in flight as to bring blossom to the bough.

‘I have summoned you!’ The tall man, teeth gritted as if still straining to hold the other in place, though his hands are at his side.

‘A fine trick, Kelem.’

‘You know me?’

‘I know everyone.’ A sharp grin. ‘You’re the door-mage.’

‘And you are?’

‘Ikol.’ His clothes change, tattered yellow checks on blue where before it was scarlet fleur de lis on grey. ‘Olik.’ He smiles a smile that dazzles and cuts. ‘Loki, if you likey.’

‘Are you a god, Loki?’ No humour in Kelem, only command. Command and a great and terrible concentration in stone-grey eyes.

‘No.’ Loki spins, regarding the doors. ‘But I’ve been known to lie.’

‘I called on the most powerful—’

‘You don’t always get what you want.’ Almost sing-song. ‘But sometimes you get what you need. You got me.’

‘You are a god?’

‘Gods are dull. I’ve stood before the throne. Wodin sits there, old one-eye, with his ravens whispering into each ear.’ Loki smiles. ‘Always the ravens. Funny how that goes.’

‘I need—’

‘Men don’t know what they need. They barely know what they want. Wodin, father of storms, god of gods, stern and wise. But mostly stern. You’d like him. And watching – always watching – oh the things that he has seen!’ Loki spins to take in the room. ‘Me, I’m just a jester in the hall where the world was made. I caper, I joke, I cut a jig. I’m of little importance. Imagine though … if it were I that pulled the strings and made the gods dance. What if at the core, if you dug deep enough, uncovered every truth … what if at the heart of it all … there was a lie, like a worm at the centre of the apple, coiled like Oroborus, just as the secret of men hides coiled at the centre of each piece of you, no matter how fine you slice? Wouldn’t that be a fine joke now?’

Kelem frowns at this nonsense, then with a quick shake of his head returns to his purpose. ‘I made this place. From my failures.’ He gestures at the doors. Thirteen, lined side by side on each wall of an otherwise bare room. ‘These are doors I can’t open. You can leave here, but no door will open until every door is unlocked. I made it so.’ A single candle lights the chamber, dancing as the occupants move, their shadows leaping to its tune.

‘Why would I want to leave?’ A goblet appears in Loki’s hand, silver and overflowing with wine as dark and red as blood. He takes a sip.

‘I command you by the twelve arch-angels of—’

‘Yes, yes.’ Loki waves away the conjuring. The wine darkens until it’s a black that draws the eye and blinds it. So black that the silver tarnishes and corrupts. So black it is nothing but the absence of light. And suddenly it’s a key. A black glass key.

‘Is that…’ there’s a hunger in the door-mage’s voice ‘…will it open them?’

‘I should hope so.’ Loki spins the key around his fingers.

‘What key is that? Not Acheron’s? Taken from heaven when—’

‘It’s mine. I made it. Just now.’

‘How do you know it will open them?’ Kelem’s gaze sweeps the room.

‘It’s a good key.’ Loki meets the mage’s eyes. ‘It’s every key. Every key that was and is, every key that will be, every key that could be.’

‘Give it to—’

‘Where’s the fun in that?’ Loki walks to the nearest door and sets his fingers to it. ‘This one.’ Each door is plain and wooden but when he touches it this door becomes a sheet of black glass, unblemished and gleaming. ‘This is the tricky one.’ Loki sets his palm to the door and a wheel appears. An eight-spoked wheel of the same black glass, standing proud of the surface, as if by turning it one might unlock and open the door. Loki doesn’t touch it. Instead he taps his key to the wall beside it and the whole room changes. Now it is a high vault, clean lines, walls of poured stone, a huge and circular silver-steel door in the ceiling. The light comes from panels set into the walls. A corridor leads off, stretching further than the eye can see. Thirteen silver-steel arches stand around the margins of the vault, each a foot from the wall, each filled with a shimmering light, as if moonbeams dance across water. Save for the one before Loki, which is black, a crystal surface fracturing the light then swallowing it. ‘Open this door and the world ends.’

Loki moves on, touching each door in turn. ‘Your death lies behind one of these other doors, Kelem.’

The mage stiffens then sneers. ‘God of tricks they—’

‘Don’t worry.’ Loki grins. ‘You’ll never manage to open that one.’

‘Give me the key.’ Kelem extends his hand but makes no move toward his guest.

‘What about that door?’ Loki looks up at the circle of silver-steel. ‘You tried to hide that one from me.’

Kelem says nothing.

‘How many generations have your people lived down here in these caves, hiding from the world?’

‘These are not caves!’ Kelem bridles. He pulls back his hand. ‘The world is poisoned. The Day of a Thousand Suns—’

‘—was two hundred years ago.’ Loki waves his key carelessly at the ceiling. The vast door groans, then swings in on its hinges, showering earth and dust upon them. It is as thick as a man is tall.

‘No!’ Kelem falls to his knees, arms above his head. The dust settles on him, making an old man of him. The floor is covered with soil, with green things growing, worms crawl, bugs scurry, and high above them, through a long vertical shaft, a circle of blue sky burns.

‘There, I’ve opened the most important door for you. Go out, claim what you can before it all goes. There are others repopulating from the east.’ Loki looks around as if seeking an exit of his own. ‘No need to thank me.’

Kelem lifts his head, rubbing the dirt from his eyes, leaving them red and watering. ‘Give me the key.’ His voice a croak.

‘You’ll have to look for it.’

‘I command you to…’ But the key is gone, Loki is gone. Only Kelem remains. Kelem and his failures.

1 (#uf0366c84-6498-5aa2-8c73-dab2f7c02570)

Petals rained down amid cheers of adoration. Astride my glorious charger at the head of Red March’s finest cavalry unit, I led the way along the Street of Victory toward the Red Queen’s palace. Beautiful women strained to escape the crowd and throw themselves at me. Men roared their approval. I waved—

Bang. Bang. Bang.

My dream tried to shape the hammering into something that would fit the story it was telling. I’ve a good imagination and for a moment everything held together. I waved to the highborn ladies adorning each balcony. A manly smirk for my sour-faced brothers sulking at the back of—

Bang! Bang! Bang!

The tall houses of Vermillion began to crumble, the crowd started to thin, faces blurred.

BANG! BANG! BANG!

‘Ah hell.’ I opened my eyes and rolled from the furs’ warmth into the freezing gloom. ‘Spring they call this!’ I struggled shivering into a pair of trews and hurried down the stairs.

The tavern room lay strewn with empty tankards, full drunks, toppled benches and upended tables. A typical morning at the Three Axes. Maeres sniffed around a scatter of bones by the hearth, wagging his tail as I staggered in.

BANG! BANG—

‘All right! All right! I’m coming.’ Someone had split my skull open with a rock during the night. Either that or I had a hell of a hangover. Damned if I knew why a prince of Red March had to answer his own front door, but I’d do anything to stop that pounding tearing through my poor head.

I picked a path through the detritus, stepping over Erik Three-Teeth’s ale-filled belly to reach the door just as it reverberated from yet another blow.

‘God damn it! I’m here!’ I shouted as quietly as I could, teeth gritted against the pain behind my eyes. Fingers fumbled with the lock bar and I pulled it free. ‘What?’ And I hauled the door back. ‘What?’

I suppose with a more sober and less sleep-addled mind I might have judged it better to stay in bed. Certainly that thought occurred to me as the fist caught me square in the face. I stumbled back, bleating, tripped over Erik and found myself on my arse staring up at Astrid, framed in the doorway by a morning considerably brighter than anything I wanted to look at.

‘You bastard!’ She stood hands on hips now. The brittle light fractured around her, sending splinters into my eyes but making a wonder of her golden hair and declaring in no uncertain terms the hour-glass figure that had set me leering at her on my first day in Trond.

‘W-what?’ I shifted my legs off Erik’s bulging stomach, and shuffled backward on my behind. My hand came away bloody from my nose. ‘Angel, sweetheart—’

‘You bastard!’ She stepped after me, hugging herself now, the cold following her in.

‘Well—’ I couldn’t argue against ‘bastard’, except technically. I put my hand in a puddle of something decidedly unpleasant and got up quickly, wiping my palm on Maeres who’d come over to investigate, tail still wagging despite the violence offered to his master.

‘Hedwig ver Sorren?’ Astrid had murder in her eyes.

I kept backing away. I might have half a foot over her in height but she was still a tall woman with a powerful right arm. ‘Oh, you don’t want to believe street talk, my sweets.’ I swung a stool between us. ‘It’s only natural that Jarl Sorren would invite a prince of Red March to his halls once he knew I was in town. Hedwig and I—’

‘Hedwig and you what?’ She took hold of the stool as well.

‘Uh, we – Nothing really.’ I tightened my grip on the stool legs. If I let go I’d be handing her a weapon. Even in my jeopardy visions of Hedwig invaded my mind, brunette, very pretty, wicked eyes, and all a man could want packed onto a short but inviting body. ‘We were barely introduced.’

‘It must have been a pretty bare introduction if it has Jarl Sorren calling out his housecarls to bring you in for justice!’

‘Oh shit.’ I let go of the stool. Justice in the north tends to mean having your ribs broken out of your chest.

‘What’s all the noise?’ A sleepy voice from behind me.

I turned to see Edda, barefoot on the stairs, our bed furs wrapped around her middle, slim legs beneath, and milk pale shoulders above, her white-blonde hair flowing across them.

Turning away was my mistake. Never take your eye off a potential foe. Especially after handing them a weapon.

‘Easy!’ A hand on my chest pushed me back down onto a floor that felt thick with grime.

‘What the—’ I opened my eyes to find a ‘someone’ looming over me, a big someone. ‘Ouch!’ A big someone poking clumsy fingers at a very painful spot over my cheekbone.

‘Just removing the splinters.’ A big fat someone.

‘Get off me, Tuttugu!’ I struggled to get up again, managing to sit this time. ‘What happened?’

‘You got hit with a stool.’

I groaned a bit. ‘I don’t remember a stool, I— OUCH! What the hell?’ Tuttugu seemed fixed set on pinching and jabbing at the sorest part of my face.

‘You might not remember the stool but I’m pulling pieces of it out of your cheek – so keep still. We don’t want to spoil those good looks, now do we?’

I did my best to hold still at that. It was true, good looks and a title were most of what I had going for me and I wasn’t keen to lose either. To take my mind off the pain I tried to remember how I had managed to get beaten with my own furniture. I drew a blank. Some vague recollection of high-pitched screaming and shouting … a memory of being kicked whilst on the floor … a glimpse through slitted eyes of two women leaving arm in arm, one petite, pale, young, the other tall, golden, maybe thirty. Neither looked back.

‘Right! Up you get. That’s the best I can do for now.’ Tuttugu hauled on my arm to get me on my feet.

I stood swaying, nauseous, hung over, perhaps still a little drunk, and – though I found it hard to credit – slightly horny.

‘Come on. We have to go.’ Tuttugu started to drag me toward the brightness of the doorway. I tried digging in my heels but to no avail.

‘Where?’ Springtime in Trond had turned out to be more bitter than a Red March midwinter and I’d no interest in exposing myself to it.

‘The docks!’ Tuttugu seemed worried. ‘We might just make it!’

‘Why? Make what?’ I didn’t remember much of the morning but I hadn’t forgotten that ‘worried’ was Tuttugu’s natural state. I shook him off. ‘Bed. That’s where I’m going.’

‘Well if that’s where you want Jarl Sorren’s men to find you…’

‘Why should I give a fig for Jarl Sorr—oh.’ I remembered Hedwig. I remembered her on the furs in the jarlshouse when everyone else was still at her sister’s wedding feast. I remembered her on my cloak during an ill-advised outdoors tryst. She kept my front warm but damn my arse froze. I remembered her upstairs at the tavern that one time she slipped her minders … I was surprised we didn’t shake all three axes down from above the entrance that afternoon. ‘Give me a moment … two moments!’ I held up a hand to stay Tuttugu and charged upstairs.

Once back in my chamber a single moment proved ample. I stamped on the loose floorboard, scooped up my valuables, snatched an armful of clothing, and was heading back down the stairs before Tuttugu had the time to scratch his chins.

‘Why the docks?’ I panted. The hills would be a quicker escape – and then a boat from Hjorl on Aöefl’s Fjord just up the coast. ‘The docks are the first place they’ll look after here!’ I’d be stood there still trying to negotiate a passage to Maladon or the Thurtans when the jarl’s men found me.

Tuttugu stepped around Floki Wronghelm, sprawled and snoring beside the bar. ‘Snorri’s down there, preparing to sail.’ He bent down behind the bar, grunting.

‘Snorri? Sailing?’ It seemed that the stool had dislodged more than the morning’s memories. ‘Why? Where’s he going?’

Tuttugu straightened up holding my sword, dusty and neglected from its time hidden on the bar shelf. I didn’t reach for it. I’m fine with wearing a sword in places where nobody is going to see it as an invitation – Trond was never such a place.

‘Take it!’ Tuttugu angled the hilt toward me.

I ignored it, wrestling myself into my clothes, the coarse weave of the north, itchy but warm. ‘Since when did Snorri have a boat?’ He’d sold the Ikea to finance the expedition to the Black Fort – that much I did remember.

‘I should get Astrid back here to see if another beating with a stool might knock some sense into you!’ Tuttugu tossed the sword down beside me as I sat to haul my boots on.

‘Astrid?… Astrid!’ A moment returned to me with crystal clarity – Edda coming down the stairs half-naked, Astrid watching. It had been a while since a morning went so spectacularly wrong for me. I’d never intended the two of them to collide in such circumstances but Astrid hadn’t struck me as the jealous sort. In fact I hadn’t been entirely sure I was the only younger man keeping her bed warm whilst her husband roamed the seas a-trading. We mostly met at her place up on the Arlls Slope, so stealth with Edda hadn’t been a priority. ‘How did Astrid even know about Hedwig?’ More importantly, how did she reach me before Jarl Sorren’s housecarls, and how much time did I have?

Tuttugu ran a hand down his face, red and sweating despite the spring chill. ‘Hedwig managed to send a messenger while her father was still raging and gathering his men. The boy galloped from Sorrenfast and started asking where to find the foreign prince. People directed him to Astrid’s house. I got all this from Olaaf Fish-hand after I saw Astrid storming down the Carls Way. So…’ He drew a deep breath. ‘Can we go now, because—’

But I was up and past him, out into the unwholesome freshness of the day, splattering through half-frozen mud, aimed down the street for the docks, the mast tops just visible above the houses. Gulls circled on high, watching my progress with mocking cries.

2 (#uf0366c84-6498-5aa2-8c73-dab2f7c02570)

If there’s one thing I like less than boats it’s being brutally murdered by an outraged father. I reached the docks painfully aware that I’d put my boots on the wrong feet and slung my sword too low so it tried to trip me at each stride. The usual scene greeted me, a waterfront crowded with activity despite the fishermen having put to sea hours earlier. The fact that the harbour lay ice-locked for the winter months seemed to set the Norsemen into a frenzy come spring – a season characterized by being slightly above the freezing point of brine rather than by the unfurling of flowers and the arrival of bees as in more civilized climes. A forest of masts painted stark lines against the bright horizon, longboats and Viking trade ships nestled alongside triple-masted merchantmen from a dozen nations to the south. Men bustled on every side, loading, unloading, doing complicated things with ropes, fishwives further back working on the nets or applying wickedly sharp knives to glimmering mounds of last night’s catch.

‘I don’t see him.’ Snorri was normally easy to spot in a crowd – you just looked up.

‘There!’ Tuttugu tugged my arm and pointed to what must be the smallest boat at the quays, occupied by the largest man.

‘That thing? It’s not even big enough for Snorri!’ I hastened after Tuttugu anyway. There seemed to be some sort of disturbance up by the harbour master’s station and I could swear someone shouted ‘Kendeth!’

I overtook Tuttugu and clattered out along the quay to arrive well ahead of him above Snorri’s little boat. Snorri looked up at me through the black and windswept tangle of his mane. I took a step back at the undisguised mistrust in his stare.

‘What?’ I held out my hands. Any hostility from a man who swings an axe like Snorri does has to be taken seriously. ‘What did I do?’ I did recall some kind of altercation – though it seemed unlikely that I’d have the balls to disagree with six and a half foot of over-muscled madman.

Snorri shook his head and turned away to continue securing his provisions. The boat seemed full of them. And him.

‘No really! I got hit in the head. What did I do?’

Tuttugu came puffing up behind me, seeming to want to say something, but too winded to speak.

Snorri let out a snort. ‘I’m going, Jal. You can’t talk me out of it. We’ll just have to see who cracks first.’

Tuttugu set a hand to my shoulder and bent as close to double as his belly would allow. ‘Jal—’ Whatever he’d intended to say past that trailed off into a wheeze and a gasp.

‘Which of us cracks first?’ It started to come back to me. Snorri’s crazy plan. His determination to head south with Loki’s key … and me equally resolved to stay cosy in the Three Axes enjoying the company until either my money ran out or the weather improved enough to promise a calm crossing to the continent. Aslaug agreed with me. Every sunset she would rise from the darkest reaches of my mind and tell me how unreasonable the Norseman was. She’d even convinced me that separating from Snorri would be for the best, releasing her and the light-sworn spirit Baraqel to return to their own domains, carrying the last traces of the Silent Sister’s magic with them.

‘Jarl Sorren…’ Tuttugu heaved in a lungful of air. ‘Jarl Sorren’s men!’ He jabbed a finger back up the quay. ‘Go! Quick!’

Snorri straightened up with a wince, and frowned back at the dock wall where chain-armoured housecarls were pushing a path through the crowd. ‘I’ve no bad blood with Jarl Sorren…’

‘Jal does!’ Tuttugu gave me a hefty shove between the shoulder blades. I balanced for a moment, arms pin wheeling, took a half-step forward, tripped over that damn sword, and dived into the boat. Bouncing off Snorri proved marginally less painful than meeting the hull face first, and he caught hold of enough of me to make sure I ended in the bilge water rather than the seawater slightly to the left.

‘What the hell?’ Snorri remained standing a moment longer as Tuttugu started to struggle down into the boat.

‘I’m coming too,’ Tuttugu said.

I lay on my side in the freezing dirty water at the bottom of Snorri’s freezing dirty boat. Not the best time for reflection but I did pause to wonder quite how I’d gone so quickly from being pleasantly entangled in the warmth of Edda’s slim legs to being unpleasantly entangled in a cold mess of wet rope and bilge water. Grabbing hold of the small mast, I sat up, cursing my luck. When I paused to draw breath it also occurred to me to wonder why Tuttugu was descending toward us.

‘Get back out!’ It seemed the same thought had struck Snorri. ‘You’ve made a life here, Tutt.’

‘And you’ll sink the damn boat!’ Since no one seemed inclined to do anything about escaping I started to fit the oars myself. It was true though – there was nothing for Tuttugu down south and he did seem to have taken to life in Trond far more successfully than to his previous life as a Viking raider.

Tuttugu stepped backward into the boat, almost falling as he turned.

‘What are you doing here, Tutt?’ Snorri reached out to steady him whilst I grabbed the sides. ‘Stay. Let that woman of yours look after you. You won’t like it where I’m bound.’

Tuttugu looked up at Snorri, the two of them uncomfortably close. ‘Undoreth, we.’ That’s all he said, but it seemed to be enough for Snorri. They were after all most likely the last two of their people. All that remained of the Uuliskind. Snorri slumped as if in defeat then moved back, taking the oars and shoving me into the prow.

‘Stop!’ Cries from the quay, above the clatter of feet. ‘Stop that boat!’

Tuttugu untied the rope and Snorri drew on the oars, moving us smoothly away. The first of Jarl Scorron’s housecarls arrived red-faced above the spot where we’d been moored, roaring for our return.

‘Row faster!’ I had a panic on me, terrified they might jump in after us. The sight of angry men carrying sharp iron has that effect on me.

Snorri laughed. ‘They’re not armoured for swimming.’ He looked back at them, raising his voice to a boom that drowned out their protests, ‘And if that man actually throws the axe he’s raising I really will come back to return it to him in person.’

The man kept hold of his axe.

‘And good riddance to you!’ I shouted, but not so loud the men on the quay would hear me. ‘A pox on Norsheim and all its women!’ I tried to stand and wave my fist at them, but thought better of it after nearly pitching over the side. I sat down heavily, clutching my sore nose. At least I was heading south at last, and that thought suddenly put me in remarkably good spirits. I’d sail home to a hero’s welcome and marry Lisa DeVeer. Thoughts of her had kept me going on the Bitter Ice and now with Trond retreating into the distance she filled my imagination once again.

It seemed that all those months of occasionally wandering down to the docks and scowling at the boats had made a better sailor of me. I didn’t throw up until we were so far from port that I could barely make out the expressions on the housecarls’ faces.

‘Best not to do that into the wind,’ Snorri said, not breaking the rhythm of his rowing.

I finished groaning before replying, ‘I know that, now.’ I wiped the worst of it from my face. Having had nothing but a punch on the nose for breakfast helped to keep the volume down.

‘Will they give chase?’ Tuttugu asked.

That sense of elation at having escaped a gruesome death shrivelled up as rapidly as it had blossomed and my balls attempted a retreat back into my body. ‘They won’t … will they?’ I wondered just how fast Snorri could row. Certainly under sail our small boat wouldn’t outpace one of Jarl Sorren’s longships.

Snorri managed a shrug. ‘What did you do?’

‘His daughter.’

‘Hedwig?’ A shake of the head and laugh broke from him. ‘Erik Sorren’s chased more than a few men over that one. But mostly just long enough to make sure they keep running. A prince of Red March though … might go the extra mile for a prince, then drag you back and see you handfasted before the Odin stone.’

‘Oh God!’ Some other awful pagan torture I’d not heard about. ‘I barely touched her. I swear it.’ Panic starting to rise, along with the next lot of vomit.

‘It means “married”,’ said Snorri. ‘Handfasted. And from what I heard you barely touched her repeatedly and in her own father’s mead hall to boot.’

I said something full of vowels over the side before recovering myself to ask, ‘So, where’s our boat?’

Snorri looked confused. ‘You’re in it.’

‘I mean the proper-sized one that’s taking us south.’ Scanning the waves I could see no sign of the larger vessel I presumed we must be aiming to rendezvous with.

Snorri’s mouth took on a stiff-jawed look as if I’d insulted his mother. ‘You’re in it.’

‘Oh come on…’ I faltered beneath the weight of his stare. ‘We’re not seriously crossing the sea to Maladon in this rowboat are we?’

By way of answer Snorri shipped the oars and started to prepare the sail.

‘Dear God…’ I sat, wedged in the prow, my neck already wet with spray, and looked out over the slate-grey sea, flecked with white where the wind tore the tops off the waves. I’d spent most of the voyage north unconscious and it had been a blessing. The return would have to be endured without the bliss of oblivion.

‘Snorri plans to put in at ports along the coast, Jal,’ Tuttugu called from his huddle in the stern. ‘We’ll sail from Kristian to cross the Karlswater. That’s the only time we’ll lose sight of land.’

‘A great comfort, Tuttugu. I always like to do my drowning within sight of land.’

Hours passed and the Norsemen actually seemed to be enjoying themselves. For my part I stayed wrapped around the misery of a hangover, leavened with a stiff dose of stool-to-head. Occasionally I’d touch my nose to make sure Astrid’s punch hadn’t broken it. I’d liked Astrid and it sorrowed me to think we wouldn’t snuggle up in her husband’s bed again. I guessed she’d been content to ignore my wanderings as long as she could see herself as the centre and apex of my attentions. To dally with a jarl’s daughter, someone so highborn, and for it to be so public, must have been more than her pride would stand for. I rubbed my jaw, wincing. Damn, I’d miss her.

‘Here.’ Snorri thrust a battered pewter mug toward me.

‘Rum?’ I lifted my head to squint at it. I’m a great believer in hair of the dog, and nautical adventures always call for a measure of rum in my largely fictional experience.

‘Water.’

I uncurled with a sigh. The sun had climbed as high as it was going to get, a pale ball straining through the white haze above. ‘Looks like you made a good call. Albeit by mistake. If you hadn’t been ready to sail I might be handfasted by now. Or worse.’

‘Serendipity.’

‘Seren-what-ity?’ I sipped the water. Foul stuff. Like water generally is.

‘A fortunate accident,’ Snorri said.

‘Uh.’ Barbarians should know their place, and using long words isn’t it. ‘Even so it was madness to set off so early in the year. Look! There’s still ice floating out there!’ I pointed to a large plate of the stuff, big enough to hold a small house. ‘Won’t be much left of this boat if we hit any.’ I crawled back to join him at the mast.

‘Best not distract me from steering then.’ And just to prove a point he slung us to the left, some lethal piece of woodwork swinging scant inches above my head as the sail crossed over.

‘Why the hurry?’ Now that the lure of three delicious women who had fallen for my ample charms had been removed I was more prepared to listen to Snorri’s reasons for leaving so precipitously. I made a vengeful note to use ‘precipitously’ in conversation. ‘Why so precipitous?’

‘We went through this, Jal. To the death!’ Snorri’s jaw tightened, muscles bunching.

‘Tell me once more. Such matters are clearer at sea.’ By which I meant I didn’t listen the first time because it just seemed like ten different reasons to pry me from the warmth of my tavern and from Edda’s arms. I would miss Edda, she really was a sweet girl. Also a demon in the furs. In fact I sometimes got the feeling that I was her foreign fling rather than the other way around. Never any talk of inviting me to meet her parents. Never a whisper about marriage to her prince … A man enjoying himself any less than I was might have had his pride hurt a touch by that. Northern ways are very strange. I’m not complaining … but they’re strange. Between the three of them I’d spent the winter in a constant state of exhaustion. Without the threat of impending death I might never have mustered the energy to leave. I might have lived out my days as a tired but happy tavernkeeper in Trond. ‘Tell me once more and we’ll never speak of it again!’

‘I told you a hundr—’

I made to vomit, leaning forward.

‘All right!’ Snorri raised a hand to forestall me. ‘If it will stop you puking all over my boat…’ He leaned out over the side for a moment, steering the craft with his weight, then sat back. ‘Tuttugu!’ Two fingers toward his eyes, telling him to keep watch for ice. ‘This key.’ Snorri patted the front of his fleece jacket, above his heart. ‘We didn’t come by it easy.’ Tuttugu snorted at that. I suppressed a shudder. I’d done a good job of forgetting everything between leaving Trond on the day we first set off for the Black Fort and our arrival back. Unfortunately it only took a hint or two for memories to start leaking through my barriers. In particular the screech of iron hinges would return to haunt me as door after door surrendered to the unborn captain and that damn key.

Snorri fixed me with that stare of his, the honest and determined one that makes you feel like joining him in whatever mad scheme he’s espousing – just for a moment, mind, until commonsense kicks back in. ‘The Dead King will be wanting this key back. Others will want it too. The ice kept us safe, the winter, the snows … once the harbour cleared the key had to be moved. Trond would not have kept him out.’

I shook my head. ‘Safe’s the last thing on your mind! Aslaug told me what you really plan to do with Loki’s key. All that talk of taking it back to my grandmother was nonsense.’ Snorri narrowed his eyes at that. For once the look didn’t make me falter – soured by the worst of days and made bold by the misery of the voyage I blustered on regardless. ‘Well! Wasn’t it nonsense?’

‘The Red Queen would destroy the key,’ Snorri said.

‘Good!’ Almost a shout. ‘That’s exactly what she should do!’

Snorri looked down at his hands, upturned on his lap, big, scarred, thick with callus. The wind whipped his hair about, hiding his face. ‘I will find this door.’

‘Christ! That’s the last place that key should be taken!’ If there really was a door into death no sane person would want to stand before it. ‘If this morning has taught me anything it’s to be very careful which doors you open and when.’

Snorri made no reply. He kept silent. Still. Nothing for long moments but the flap of sail, the slop of wave against hull. I knew what thoughts ran through his head. I couldn’t speak them, my mouth would go too dry. I couldn’t deny them, though to do so would cause me only an echo of the hurt such a denial would do him.

‘I will get them back.’ His eyes held mine and for a heartbeat made me believe he might. His voice, his whole body shook with emotion, though in what part sorrow and what part rage I couldn’t say.

‘I will find this door. I will unlock it. And I will bring back my wife, my children, my unborn son.’

3 (#uf0366c84-6498-5aa2-8c73-dab2f7c02570)

‘Jal?’ Someone shaking my shoulder. I reached to draw Edda in closer and found my fingers tangled in the unwholesome ginger thicket of Tuttugu’s beard, heavy with grease and salt. The whole sorry story crashed in on me and I let out a groan, deepened by the returning awareness of the swell, lifting and dropping our little boat.

‘What?’ I hadn’t been having a good dream, but it was better than this.

Tuttugu thrust a half-brick of dark Viking bread at me, as if eating on a boat were really an option. I waved it away. If Norse women were a highpoint of the far north then their cuisine counted as one of the lowest. With fish they were generally on a good footing, simple, plain fare, though you had to be careful or they’d start trying to feed it to you raw, or half rotted and stinking worse than corpse flesh. ‘Delicacies’ they’d call it … The time to eat something is the stage between raw and rotting. It’s not the alchemy of rockets! With meat – what meat there was to be found clinging to the near vertical surfaces of the north – you could trust them to roast it over an open fire. Anything else always proved a disaster. And with any other kind of eatable the Norsemen were likely to render it as close to inedible as makes no difference using a combination of salt, pickle, and desiccated nastiness. Whale meat they preserved by pissing on it! My theory was that a long history of raiding each other had driven them to make their foodstuffs so foul that no one in their right mind would want to steal it. Thereby ensuring that, whatever else the enemy might carry off, women, children, goats, and gold, at least they’d leave lunch behind.

‘We’re coming in to Olaafheim,’ Tuttugu said, pulling me out of my doze again.

‘Whu?’ I levered myself up to look over the prow. The seemingly endless uninviting coastline of wet black cliffs protected by wet black rocks had been replaced with a river mouth. The mountains leapt up swiftly to either side, but here the river had cut a valley whose sides might be grazed, and left a truncated floodplain where a small port nestled against the rising backdrop.

‘Best not to spend the night at sea.’ Tuttugu paused to gnaw at the bread in his hand. ‘Not when we’re so close to land.’ He glanced out west to where the sun plotted its descent toward the horizon. The quick look he shot me before settling back to eat told me clear enough that he’d rather not be sharing the boat with me when Aslaug came to visit at sunset.

Snorri tacked across the mouth of the river, the Hœnir he called it, angling across the diluted current toward the Olaafheim harbour. ‘These are fisher folk and raiders, Jal. Clan Olaaf, led by jarls Harl and Knütson, twin sons of Knüt Ice-Reaver. This isn’t Trond. The people are less … cosmopolitan. More—’

‘More likely to split my skull if I look at them wrong,’ I interrupted him. ‘I get the picture.’ I held a hand up. ‘I promise not to bed any jarl’s daughters.’ I even meant it. Now we were actually on the move I had begun to get excited about the prospect of a return to Red March, to being a prince again, returning to my old diversions, running with my old crowd, and putting all this unpleasantness behind me. And if Snorri’s plans led him along a different path then we’d just have to see what happened. We’d have to see, as he put it earlier, who cracked first. The bonds that bound us seemed to have weakened since the event at the Black Fort. We could separate five miles and more before any discomfort set in. And as we’d already seen, if the Silent Sister’s magic did fracture its way out of us the effect wasn’t fatal … except for other people. If push came to shove Aslaug’s advice seemed sound. Let the magic go, let her and Baraqel be released to return to their domains. It would be far from pleasant if last time was anything to go by, but like pulling a tooth it would be much better afterward. Obviously though, I’d do everything I could to avoid pulling that particular tooth – unless it meant traipsing into mortal danger on Snorri’s quest. My own plan involved getting him to Vermillion and having Grandmother order her sister to effect a more gentle release of our fetters.

We pulled into the harbour at Olaafheim with the shadows of boats at anchor reaching out toward us across the water. Snorri furled the sail, and Tuttugu rowed toward a berth. Fishermen paused from their labours, setting down their baskets of hake and cod to watch us. Fishwives laid down half-stowed nets and crowded in behind their men to see the new arrivals. Norsemen busy with some or other maintenance on the nearest of four longboats leaned out over the sides to call out in the old tongue. Threats or welcome I couldn’t tell, for a Viking can growl out the warmest greeting in a tone that suggests he’s promising to cut your mother’s throat.

As we coasted the last yard Snorri vaulted up onto the harbour wall from the side of the boat. Locals crowded him immediately, a sea of them surging around the rock. From the amount of shoulder-slapping and the tone of the growling I guessed we weren’t in trouble. The occasional chuckle even escaped from several of the beards on show, which took some doing as the Clan Olaaf grew the most impressive facial hair I’d yet seen. Many favoured the bushy explosions that look like regular beards subjected to sudden and very shocking news. Others had them plaited and hanging in two, three, sometimes five iron-capped braids reaching down to their belts.

‘Snorri.’ A newcomer, well over six foot and at least that wide, fat with it, arms like slabs of meat. At first I thought he was wearing spring furs, or some kind of woollen over-shirt, but as he closed on Snorri it became apparent that his chest hair just hadn’t known when to stop.

‘Borris!’ Snorri surged through the others to clasp arms with the man, the two of them wrestling briefly, neither giving ground.

Tuttugu finished tying up and with a pair of men on each arm the locals hauled him onto the dock. I clambered quickly up behind him, not wishing to be man-handled.

‘Tuttugu!’ Snorri pointed him out for Borris. ‘Undoreth. We might be the last of our clan, him and I…’ He trailed off, inviting any present to make a liar of him, but none volunteered any sighting of other survivors.

‘A pox on the Hardassa.’ Borris spat on the ground. ‘We kill them where we find them. And any others who make cause with the Drowned Isles.’ Mutters and shouts went up at that. More men spitting when they spoke the word ‘necromancer’.

‘A pox on the Hardassa!’ Snorri shouted. ‘That’s something to drink to!’

With a general cheering and stamping of feet the whole crowd started to move toward the huts and halls behind the various fisheries and boat sheds of the harbour. Snorri and Borris led the way, arms over each other’s shoulders, laughing at some joke, and I, the only prince present, trailed along unintroduced at the rear with the fishermen, their hands still scaly from the catch.

I guess Trond must have had its own stink, all towns do, but you don’t notice it after a while. A day at sea breathing air off the Atlantis Ocean tainted with nothing but a touch of salt proved sufficient to enable my nostrils to be offended by my fellow men once more. Olaafheim stank of fresh fish, sweat, stale fish, sewers, rotting fish, and uncured hides. It only got worse as we trudged up through a random maze of split-log huts, turf roofed and close to the ground, each with nets at the front and fuel stacked to the sheltered landward side.

Olaafheim’s great hall stood smaller than the foyer of my grandmother’s palace, a half timbered structure, mud daubed into any nook or cranny where the wind might slide its fingers, wooden shingles on the roof, patchy after the winter storms.

I let the Norsemen crowd in ahead of me and turned back to face the sea. In the west clear skies showed a crimson sun descending. Winter in Trond had been a long cold thing. I may have spent more time than was reasonable in the furs but in truth most of the north does the same. The night can last twenty hours and even when the day finally breaks it never gets above a level of cold I call ‘fuck that’ – as in you open the door, your face freezes instantly to the point where it hurts to speak, but manfully you manage to say ‘fuck that’, before turning round, and going back to bed. There’s little to do in a northern winter but to endure it. In the very depths of the season sunrise and sunset get so close together that if Snorri and I were to be in the same room Aslaug and Baraqel might even get to meet. A little further north and they surely would, for there the days dwindle into nothing and become a single night that lasts for weeks. Not that Aslaug and Baraqel meeting would be a good idea.

Already I could feel Aslaug scratching at the back of my mind. The sun hadn’t yet touched the water but the sea burned bloody with it and I could hear her footsteps. I recalled how Snorri’s eyes would darken when she used to visit him. Even the whites would fill with shadow, and become for a minute or two so wholly black that you might imagine them holes into some endless night, from which horrors might pour if he but looked your way. I held that to be a clash of temperaments though. If anything my vision always seemed clearer when she came. I made sure to be alone each sunset so we could have our moment. Snorri described her as a creature of lies, a seducer whose words could turn something awful into an idea that any reasonable man would consider. For my part I found her very agreeable, though perhaps a little excessive, and definitely less concerned about my safety than I am.

The first time Aslaug came to me I had been surprised to find her so close to the image Snorri’s tales had painted in my mind. I told her so and she laughed at me. She said men had always seen what they expected to see but that a deeper truth ran beneath that fact. ‘The world is shaped by mankind’s desires and fears. A war of hope against dread, waged upon a substrate that man himself made malleable though he has long forgotten how. All men and all men’s works stand on feet of clay, waiting to be formed and reformed, forged by fear into monsters from the dark core of each soul, waiting to rend the world asunder.’ That’s how she introduced herself to me.

‘Prince Jalan.’ Aslaug stepped from the shadows of the hall. They clung to her, dark webs, not wanting to release their hold. She pulled clear as the sun kissed the horizon. No one would mistake her for human but she wore a woman’s form and wore it well, her flesh like bone, but dipped in ink so it soaked into every pore, revealing the grain, gathering black in any hollow. She fixed me with eyes that held no colour, only passions, set in a narrow and exquisite face. Oil-dark hair framed her, falling in unnatural coils and curls. Her beauty owed something to the praying mantis, something to the inhumanity of Greek sculpture. Mask or not though, it worked on me. I’m easily led in matters of the flesh. ‘Jalan,’ she said again, stepping around me. She wore tatters of darkness as a gown.

I didn’t answer, or turn to follow her. Villagers were still arriving, and the cheers and laughter from inside the hall were drawing more by the minute. None of them would see Aslaug but if they saw me spinning around and talking to the empty air it wouldn’t look good. Northmen are a superstitious lot, and frankly with what I’d seen over the last few months they were right to be so. Superstition though does tend to have a sharp end, and I didn’t want to find myself impaled on it.

‘Why are you out here in the wilds with all these ill-smelling peasants?’ Aslaug reappeared at my left shoulder, her mouth close to my ear. ‘And why,’ – a harder edge to her tone, eyes narrowing – ‘is that light-sworn here? I can smell him. He was going away…’ A tilt of her head. ‘Jalan? Have you followed him? Tagged along like a dog at heel? We’ve talked about this, Jalan. You’re a prince, a man of royal blood, in line for the throne of Red March!’

‘I’m going home.’ I whispered it, hardly a twitch in my lips.

‘Leaving your beauties behind?’ She always held a note of disapproval when it came to my womanizing. Obviously the jealous type.

‘I thought it time. They were getting clingy.’ I rubbed the side of my head, not convinced that Tuttugu had gotten all the splinters out.

‘For the better. In Red March we can begin to clear your path to succession.’ A smile lit her face, the sky crimson behind her with the sun’s death throes.

‘Well…’ My own lips curled with an echo of her expression. ‘I’m not one for murder. But if a whole bunch of my cousins fell off a cliff I wouldn’t lose any sleep over it.’ I’d found it paid to play along with her. Whilst I’d rejoice in any misfortune that fate might drop upon my cousins, three or four of them in particular, I’ve never had an appetite for the more lethal games played at some courts with knife and poison. My own vision for my glorious path to the throne involved toadying and favouritism, lubricated with tales of heroism and reports of genius. Once selected as Grandmother’s favourite and promoted unfairly into the position of heir it would just be a case of the old woman having a timely heart attack and my reign of pleasure would begin!

‘You know that Snorri will be plotting your destruction, Jalan?’ She reached an arm around me, the touch cold but somehow thrilling too, filled with all the delicious possibilities that the night hides. ‘You know what Baraqel will be instructing. He told you the same when Snorri kept me within him.’

‘I trust Snorri.’ If he had wanted me dead he could have done it many times over.

‘For how long, Prince Jalan? For how long will you trust him?’ Her lips close to mine now, head haloed with the last rays of the sunset. ‘Don’t trust the light, Prince Jalan. The stars are pretty but the space between them is infinite and black with promise.’ Behind me I could almost hear her shadow mix with mine, its dry spider-legs rustling one against the next. ‘Returning with your body and the right story to Vermillion would earn Snorri gratitude in many circles for many reasons…’

‘Good night, Aslaug.’ I clenched what could be clenched and kept from shuddering. In the last moments before the dark took her she was always at her least human, as if her presence outlasted her disguise for just a heartbeat.

‘Watch him!’ And the shadows pulled her down as they merged into the singular gloom that would deepen into night.

I turned and followed the locals into their ‘great’ hall. My moments with Aslaug always left me a touch less tolerant of sweaty peasants and their crude little lives. And perhaps Snorri did bear watching. He had after all been on the point of abandoning me when I most needed help. A day later and I could have been subjected to all the horrors of handfasting, or some even crueller form of Viking justice.

4 (#ulink_4c7203f6-ec86-5441-b5bc-d0327234004b)

Three long tables divided the mead hall, now lined by men and women raising foaming horn and dripping tankard. Children, some no more than eight or nine, ran back and forth with pitchers from four great barrels to keep any receptacle from running dry. A great fire roared in the hearth, fish roasting on spits set before it. Hounds bickered around the margins of the room, daring a kicking to run beneath the tables should anything fall. The heat and roar and stink of the place took a moment’s getting used to after plunging in from the frigid spring evening. I plotted a course toward the rear of the hall, giving the dogs a wide berth. Animals are generally good judges of character – they don’t like me – except for horses which, for reasons I’ve never understood, give me their all. Perhaps it’s our shared interest in running away that forms the bond.

Snorri and Borris sat close to the fire, flanked by Olaafheim’s warriors. Most of the company appeared to have brought their axes out for the evening’s drinking, setting them across the tabletop in such a crowd that putting down a drink became a tricky task. Snorri turned as I approached, and boomed out for a space to be made. A couple of grumbles went up at that, soon silenced with mutters of ‘berserker’. I squeezed down onto a narrow span of arse-polished bench, trying not to show my displeasure at being wedged in so tightly among hairy brigands. My tolerance for such familiarities had increased during my time at the Three Axes as owner and operator … well, in truth I paid for Eyolf to keep bar and Helga and Gudrun to serve tables … but still, I was there in spirit. In any event, although my tolerance had increased it still wasn’t high and at least in Trond you got a better quality of bearded, axe-wielding barbarian. Faced with the present situation though, not to mention a table full of axes, I did what any man keen on leaving with the same number of limbs that he entered with would do. I grinned like an idiot and bore it.

I reached for the brimming flagon brought to me by a blonde and barefoot child and decided to get drunk. It would probably keep me out of trouble and the possibility that I might pass the whole trip to the continent in a state of inebriation did seem inviting. One worry stayed my hand however. Though it pained me to admit it, my grandmother’s blood did seem to have shown in me. Snorri or Tuttugu had already mentioned my … disability to our hosts. In the troll-wrestling heart of the north being a berserker seemed to carry a good deal of cachet, but any right-thinking man would tell you what a terrible encumbrance it is. I’ve always been sensibly terrified of battle. The discovery that if I get pushed too far I turn into a raging maniac who throws himself headlong into the thickest of the fighting was hardly comforting. A wise man’s biggest advantage is in knowing the ideal time to run away. That sort of survival strategy is somewhat impaired by a tendency to start frothing at the mouth and casting aside all fear. Fear is a valuable commodity, it’s commonsense compressed into its purest form. A lack of it is not a good thing. Fortunately it took quite a lot of pushing to get my hidden berserker out into the open and to my knowledge it had only ever happened twice. Once at the Aral Pass and once in the Black Fort. If it never happened again that would be fine with me.

‘…Skilfar…’ A one-eyed man opposite Snorri, speaking into his ale horn. I picked out the one word, and that was plenty.

‘What?’ I knocked back the rest of my own ale, wiping the suds from my whiskers, a fine blond set I’d cultivated to suit the climate. ‘I’m not going back there, Snorri, no way.’ I remembered the witch in her cavern, her plasteek legion all around. She’d scared the hell out of me. I still had nightmares…

‘Relax.’ Snorri gave me that winning smile of his. ‘We don’t have to.’

I did relax, slumping forward as I let go of a tension I hadn’t known was there. ‘Thank God.’

‘She’s still in her winter seat. Beerentoppen. It’s a mountain of ice and fire, not too far inland, it’ll be our last stop before we leave the north just a few days down the coast and strike out for Maladon across open sea.’

‘Hell no!’ It had been the woman that scared me, not the tunnels and statues – well, they had too, but the point was that I wasn’t going. ‘We’ll head south. The Red Queen will have any answers we need.’

Snorri shook his head. ‘I have questions that won’t wait, Jal. Questions that need a little northern light shed on them.’

I knew what he wanted to talk about – that damned door. If he took the key to Skilfar, though, she’d probably take it off him. I didn’t doubt for a moment that she could. Still, it would be no skin off my nose if she stole it. A thing that powerful would be safer in the old witch’s keeping anyhow. Far from where I intended to be and out of the Dead King’s reach.

‘All right.’ I cut across the one-eyed warrior again. ‘You can go. But I’m staying in the boat!’

The fellow across from Snorri turned a cold blue eye my way, the other socket empty, the firelight catching the twitch of ugly little muscles in the shadowed hollow. ‘This fit-firar speaks for you now, Snorri?’

I knew the insult to be a grim one. The Vikings can think of nothing worse to call you than ‘land man’, one who doesn’t know the sea. That’s the trouble with these backwater villages – everyone’s tetchy. They’re all ready to jump up at a moment’s notice and spill your guts. It’s over-compensation of course, for living in freezing huts on an inhospitable beach. At home I’d damn the fellow’s eyes … well eye at least … and let one half of the palace guard hold me back while the other half beat him out of town. The trouble with a friend like Snorri is that he’s the sort to take things at face value and think I really did want to defend my own honour. Knowing Snorri he’d stand by clapping while the savage carved me up.

The man, Gauti I think Snorri had called him, had one hand on the axe before him, casual enough, fingers spread, but he kept that cold eye on me and there was little to read in it that wasn’t murder. This could go very wrong, very quickly. The sudden urge to piss nearly overtook me. I smiled the bold Jalan smile, ignoring the sick feeling in my stomach, and drew my dagger, a wicked piece of black iron. That got some attention, though less than in any place I’d ever seen an edge drawn before. I did at least get the satisfaction of seeing Gauti flinch, his fingers half closing about his axe hilt. To my credit, I do look like the kind of hero who would demand satisfaction and have the skill to take it.

‘Jal…’ Snorri with a half frown, gesturing with his eyes at the eight inches of knife in my hand.

I pushed aside some axe hafts and in a sudden move inverted my blade so the point hovered a quarter inch above the table. Again Gauti’s eye twitched. I saw Snorri quietly lay his hand on the man’s axe head. Several warriors half rose then settled back in their places.

One great asset in my career as secret coward has been a natural ability to lie fluently in body language. Half of it is … what did Snorri call it? Serendipity. Pure lucky accident. When scared I flush scarlet, but in a fit young man overtopping six foot by a good two inches it usually comes across as outrage. My hands also rarely betray me. I may be quivering with fright inside but they hold steady. Even when the terror is so much that they do finally shake it’s often as not mistaken as rage. Now though, as I set knifepoint to wood, my hands kept firm and sure. In a few strokes I sketched out an irregular blob with a horn at the top and lobe at the bottom.

‘What is it?’ The man across from me.

‘A cow?’ A woman of middle years, very drunk, leaning over Snorri’s shoulder.

‘That, men of the clan Olaff, is Scorron, the land of my enemies. These are the borders. This…’ I scored a short line across the bottom of the lobe. ‘This is the Aral Pass where I taught the Scorron army to call me “devil”.’ I looked up to meet Gauti’s singular glare. ‘And you will note that not one of these borders is a coastline. So if I were a man of the sea it would mean, in my country, that I could never close with my enemy. In fact every time I set sail I would be running away from them.’ I stuck the knife firmly in the centre of Scorron. ‘Where I come from “land men” are the only men who can go to war.’ I let a boy refill my tankard. ‘And so we learn that insults are like daggers – it matters which way you point them, and where you stand.’ And I threw my head back to drain my cup.

Snorri pounded the table, the axes danced, and the laughter came. Gauti leaned back, sour but his ill-temper having lost its edge. The ale flowed. Codfish were brought to table along with some kind of salty grain-mash and dreadful little sea-weed cakes burned nearly black. We ate. More ale flowed. I found myself talking drunkenly to a greybeard with more scar than face about the merits of different kinds of longboat – a subject I acquired my ‘expertise’ on in many separate pieces during innumerable similar drunken conversations with regulars back at the Three Axes. More ale, spilled, splashed, gulped. I think we’d got onto knots by the time I slipped gracefully off the bench and decided to stay where I was.

‘Hedwig,’ I grumbled, still half asleep. ‘Get off me, woman.’

The licking paused, then started up again. I wondered vaguely where I was, and when Hedwig’s tongue had got quite so long. And sloppy. And stinky.

‘Get off!’ I swiped at the dog. ‘Bloody mutt.’ I raised myself on one elbow, still at least half-drunk. The hearth’s glowing embers painted the hall in edge and shadow. Hounds slunk beneath the tables, searching for scraps. I could make out half a dozen drunks snoring on the floor, lying where they fell, and Snorri, stretched out along the central table, head on his pack, deep in his slumbers.

I got up, unsteady, stomach lurching. Although the hall smelled as if pissing in it might improve matters, I wove a path toward the main doors. In the gloom I might hit a sleeping Viking and it would prove hard to talk my way out of that one.

I reached the double doors and heaved open the one on the left, the hinges squealing loud enough to wake the dead – but apparently nobody else – and stepped out. My breath plumed before me and the moonlit square lay glittering with frost. Another fine spring night in the north. I took a pace to the left and started to answer nature’s call.

Beneath the splash of borrowed ale lay the slap of waves against the harbour wall, beneath that the murmur of surf slopping half-heartedly up the distant beach that slanted down to the river, and beneath that … a quiet that prickled the hairs at the back of my neck. I strained my ears, finding nothing to warrant my unease, but even in my cups I have a sense for trouble. Since Aslaug’s arrival the night seemed to whisper to me. Tonight it held its tongue.

I turned, still fumbling to lace my fly, and found instead that I needed to go again, right away. Standing no more than ten yards from me was the biggest wolf ever. I’d heard tall stories aplenty in the Three Axes and I’d been prepared to believe the north bred bigger wolves than might be found down south. I’d even seen a direwolf with my own eyes, albeit it stuffed and mounted in the entrance hall to Madam Serene’s Pleasure Palace down on Magister Street, Vermillion. The thing before me had to be one of the Fenris breed they spoke about in Trond. It stood as tall as a horse, wider in its shaggy coat, its mouth full of sharp ivory gleaming in the moonlight.

I stood there, stock still, still draining onto the ground between my feet. The beast moved forward, no snarl, no prowling, just a quick but slightly ungainly advance. It didn’t occur to me to reach for my sword. The wolf looked as though it might simply bite the sharp end off in any case. Instead I just stood there, making a puddle. I normally pride myself on being the type of coward who acts in the moment, running away when it counts rather than being rooted to the spot. This time however the weight of terror proved too great to run with.

Not until the huge beast charged past me, crashing open the double doors and rushing on into the great hall did I find the presence of mind to start my escape. I ran, holding my breath against the carrion reek of the thing. I got as far as the edge of the square, driven by the awful screams and howls behind me, before my brain dropped anchor. Dogs from the hall ran yelping past me. I came up short, panting – mostly in fear since I hadn’t run very far – and drew my sword. Ahead of me in the blind night could be any number of similar monsters. Wolves hunt in packs after all. Did I want to be alone in the dark with the beast’s friends, or would the safest place be with Snorri and a dozen other Vikings facing the one I’d seen?

All across Olaafheim doors were being kicked open, flames kindled. Hounds, that had been taken unawares, now gave voice, and cries of ‘To arms!’ started to ring out. Gritting my teeth, I turned back, making no effort to hurry. It sounded like hell in there: men’s screams and oaths, crashing and splintering, but strangely not a single snarl or wolf-howl. I’d seen dog fights before and they’re loud affairs. Wolves, it seemed, were given to biting their tongues – yours too, no doubt, if they got a chance!

As I drew closer to the hall the cacophony from within grew less loud, just groans, grunts, the scrape of claw on stone. My pace slowed to a crawl. Only the sounds of activity at my back kept me moving at all. I couldn’t be seen to be just standing there while men died only yards away. Heart racing, feet anything but, I made it to the doorway and eased my head around so one eye could see within.

Tables lay upended, their legs a short and drunken forest shifting in the fire glow. Men, or rather pieces of men, scattered the floor amid dark lakes and darker smears. At first I couldn’t see the Fenris wolf. A grunt of effort drew my eyes to the deepest shadow at the side of the hall. The beast stood hunched over, worrying at something on the ground. Two axes jutted from its side, one stood bedded in its back. I could see its great jaws wide about something, and a man’s legs straining beneath its snout, covered in a black slime of blood and slobber. Somehow I knew who it was, trapped in that maw.

‘Snorri!’ The shout burst from me without permission. I clapped a hand to my mouth in case any more foolishness might emerge. The last thing I wanted was for that awful head to turn my way. To my horror I found that I’d stepped into the doorway – the absolute worst place to be, silhouetted by moonlight, blocking the exit.

‘To arms!’

‘To the hall!’ Cries from all directions now.

Behind me I could hear the pounding of many feet. No retreat that way. The Norse will string a coward up by his thumbs and cut off bits he needs. I stepped in quickly to make myself a less obvious target, and edged along the inner wall, trying not to breathe. Vikings started to arrive at the doorway behind me, crowding to get through.

As I watched the wolf a hand, looking child-size against the scale of the creature, slid up from the far side of its head and clamped between its eyes. A glowing hand. A hand becoming so brilliant that the whole room lit almost bright as day. Exposed by the light, I did what any cockroach does when someone unhoods a lantern in the kitchens. I raced for cover, leaping toward the shelter of a section of table fallen on its side part way between us.

The light grew still more dazzling and half-blinded I staggered across a torso, fell over the table, and sprawled forward with several lunging steps, desperate to remain on my feet. My outstretched sword sunk into something soft, grating across bone, and a moment later an immense weight fell across me, taking away all illumination. And all the other stuff too.

5 (#ulink_4ae48c33-a0e0-51fe-ae9c-c9f23ec5a0a3)

‘…underneath! It’s taken six men to get him out.’ A woman’s voice, tinged with wonder.

I felt as if I were lifted up. Carried away.

‘Steady!’

‘Easy…’

A warm wet cloth passed across my forehead. I snuggled into the softness cradling me. The world lay a pleasant distance away, only snatches of conversation reaching me as I dozed.

In my dream I wandered the empty palace of Vermillion on a fine summer’s day, the light streaming in through tall windows overlooking the city’s basking sprawl.

‘…hilt deep! Must have reached the heart…’ A man’s voice.

I was moving. Borne along. The motion halfway between the familiar jolt of a horse and the despised rise and fall of the ocean.

‘…saw his friend…’

‘Heard him shout in the doorway. “Snorri!” He roared it like a Viking…’

The world grew closer. I didn’t want it to. I was home. Where it was warm. And safe. Well, safer. All the north had to offer was a soft landing. The woman holding me had a chest as mountainous as the local terrain.

‘…charged straight at it…’

‘…dived at it!’

The creak of a door. The raking of coals.

‘…berserker…’

I turned from the sun-drenched cityscape back into the empty palace gallery, momentarily blind.

‘…Fenris…’

The sunspots cleared from my eyes, the reds and greens fading. And I saw the wolf, there in the palace hall, jaws gaping, ivory fangs, scarlet tongue, ropes of saliva, hot breath…

‘Arrrg!’ I jerked upright, my head coming clear of Borris’s hairy man-breasts. Did the man never wear a shirt?

‘Steady there!’ Thick arms set me down as easily as a child onto a fur-laden cot. A smoky hut rose about us, larger than most, people crowded round on all sides.

‘What?’ I always ask that – though on reflection I seldom want to know.

‘Easy! It’s dead.’ Borris straightened up. Warriors of the clan Olaaf filled the roundhouse, also a matronly woman with thick blonde plaits and several buxom younger women – presumably the wife and daughters.

‘Snorri—’ I started before noticing him lying beside me, unconscious, pale – even for a northman – and sporting several nasty gashes, one of them an older wound sliced down across his ribs, angry and white-crusted. Even so he looked in far better shape than a man should after being gnawed on by a Fenris wolf. The markings about his upper arms stood out in sharp contrast against marble flesh, the hammer and the axe in blue, runes in black, trapping my attention for a moment. ‘How?’ I didn’t feel up to sentences containing more than one word.

‘Had a shield jammed in the beast’s mouth. Wedged open!’ Borris said.

‘Then you killed it!’ One of his daughters, her chest almost as developed as his.

‘We got your sword out.’ A warrior from the crowd, offering me my blade, hilt first, almost reverential. ‘Took some doing!’

The creature’s weight had driven the blade home as it fell.

I recalled how wide the wolf’s mouth had been around Snorri, and the lack of chewing going on. Closing my eyes I saw that brilliant hand pressed between the wolf’s eyes.

‘I want to see the creature.’ I didn’t, but I needed to. Besides, it wasn’t often I got to play the hero and it probably wouldn’t last long past Snorri regaining his senses. With some effort I managed to stand. Drawing breath proved the hardest part, the wolf had left me with bruised ribs on both sides. I was lucky it hadn’t crushed them all. ‘Hell! Where’s Tuttugu?’

‘I’m here!’ The voice came from behind several broad backs. Men pulled aside to reveal the other half of the Undoreth, grinning, one eye closing as it swelled. ‘Got knocked into a wall.’

‘You’re making a habit of that.’ It surprised me how pleased I was to see him in one piece. ‘Let’s go!’

Borris led the way, and flanked by men bearing reed torches I hobbled after, clutching my ribs and cursing. A pyramidal fire of seasoned logs now lit the square and a number of injured men were laid out on pallets around it, being treated by an ancient couple, both shrouded in straggles of long white hair. I hadn’t thought from my brief time in the hall that anyone had survived, but a wounded man has an instinct for rolling into any cranny or hidey hole that will take him. In the Aral Pass we’d pulled dead men from crevices and fox dens, some with just their boots showing.

Borris took us past the casualties and up to the doors of the great hall. A small man with a big warty blemish on his cheek waited guard, clutching his spear and eyeing the night.

‘It’s dead!’ The first thing he said to us. He seemed distracted, scratching at his overlarge iron helm as if that might satisfy whatever itched him.

‘Well of course it’s dead!’ Borris said, pushing past. ‘The berserker prince killed it!’

‘Of course it’s dead,’ I echoed as I passed the little fellow, allowing myself a touch of scorn. I couldn’t say why the thing had chosen that moment to fall on me, but its weight had driven my sword hilt-deep, and even a wolf as big as a horse isn’t going to get up again after an accident like that. Even so, I felt troubled. Something about Snorri’s hands glowing like that…

‘Odin’s balls! It stinks!’ Borris, just ahead of me.

I drew breath to point out that of course it did. The hall had stunk to heaven but to be fair it had been only marginally worse than the aroma of Borris’s roundhouse, or in fact Olaafheim in general. My observations were lost in a fit of choking though as the foulness invaded my lungs. Choking with badly bruised ribs is a painful affair and takes your mind off things, like standing up. Fortunately Tuttugu caught hold of me.

We advanced, breathing in shallow gasps. Lanterns had been lit and placed on the central table, now set back on its feet. Some kind of incense burned in pots, cutting through the reek with a sharp lavender scent.

The dead men had been laid out before the hearth, parts associated. I saw Gauti among them, bitten clean in half, his eye screwed shut in the agony of the moment, the empty socket staring at the roof beams. The wolf lay where it had fallen whilst savaging Snorri. It sprawled on its side, feet pointing at the wall. The terror that had infected me when I first saw it now returned in force. Even dead it presented a fearsome sight.

The stench thickened as we approached.

‘It’s dead,’ Borris said, walking toward the dangerous end.

‘Well of course—’ I broke off. The thing reeked of carrion. Its fur had fallen out in patches, the flesh beneath grey. In places where it had split worms writhed. It wasn’t just dead – it had been dead for a while.

‘Odin…’ Borris breathed the word through the hand over his face, finding no parts of the divine anatomy to attach to the oath this time. I joined him and stared down at the wolf’s head. Blackened skull would be a more accurate description. The fur had gone, the skin wrinkled back as if before a flame, and on the bone, between eye sockets from which ichor oozed, a hand print had been seared.

‘The Dead King!’ I swivelled for the door, sword in fist.

‘What?’ Borris didn’t move, still staring at the wolf’s head.

I paused and pointed toward the corpses. As I did so Gauti’s good eye snapped open. If his stare had been cold in life now all the winters of the Bitter Ice blew there. His hands clawed at the ground, and where his torso ended, in the red ruin hanging below his ribcage, pieces began to twitch.

‘Burn the dead! Dismember them!’ And I started to run, clutching my sides with one arm, each breath sharp-edged.

‘Jal, where—’ Tuttugu tried to catch hold of me as I passed him.

‘Snorri! The Dead King sent the wolf for Snorri!’ I barged past wart-face on the door and out into the night.

What with my ribs and Tuttugu’s bulk neither of us was the first to get back to Borris’s house. Swifter men had alerted the wife and daughters. Locals were already arriving to guard the place as we ducked in through the main entrance. Snorri had got himself into a sitting position, showing off the over-muscled topology of his bare chest and stomach. He had the daughters fussing around him, one stitching a tear on his side while another cleaned a wound just below his collarbone. I remembered when I had been light-sworn, carrying Baraqel within me, just how much it took out of me to incapacitate a single corpse man. Back on the mountainside just past Chamy-Nix, when Edris’s men had caught us, I’d burned through the forearms of the corpse that had been trying to strangle me. The effort had left me helpless. The fact that Snorri could even sit after incinerating the entire head of a giant dead-wolf spoke as loudly about his inner strength as all that muscle did about his outer strength.

Snorri looked up and gave me a weary grin. Having been at different times both light-sworn and now dark-sworn I have to say the dark side has it easier. The power Snorri and I had used on the undead was the same healing that we had both used to repair wounds on others. It drew on the same source of energy, but healing undead flesh just burns the evil out of it.