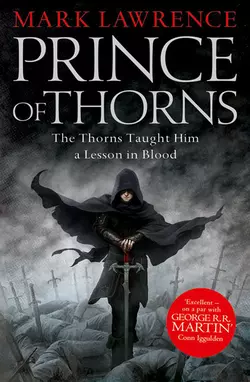

Prince of Thorns

Mark Lawrence

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежное фэнтези

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 728.57 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the publisher that brought you Game of Thrones… Prince of Thorns is the first volume in a powerful epic fantasy trilogy, original, absorbing and challenging.Before the thorns taught me their sharp lessons and bled weakness from me I had but one brother, and I loved him well. But those days are gone and what is left of them lies in my mother′s tomb. Now I have many brothers, quick with knife and sword, and as evil as you please. We ride this broken empire and loot its corpse. They say these are violent times, the end of days when the dead roam and monsters haunt the night. All that′s true enough, but there′s something worse out there, in the dark. Much worse.From being a privileged royal child, raised by a loving mother, Jorg Ancrath has become the Prince of Thorns, a charming, immoral boy leading a grim band of outlaws in a series of raids and atrocities. The world is in chaos: violence is rife, nightmares everywhere. Jorg has the ability to master the living and the dead, but there is still one thing that puts a chill in him. Returning to his father′s castle Jorg must confront horrors from his childhood and carve himself a future with all hands turned against him.Mark Lawrence′s debut novel tells a tale of blood and treachery, magic and brotherhood and paints a compelling and brutal, and sometimes beautiful, picture of an exceptional boy on his journey toward manhood and the throne.