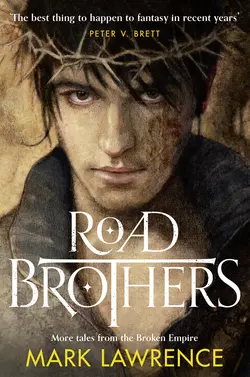

Road Brothers

Mark Lawrence

A volume of short stories by the bestselling author of THE BROKEN EMPIRE series, Mark LawrenceThis is a collection of fourteen stories of murder, mayhem, pathos, and philosophy, all set in the world of the Broken Empire.Within these pages, you will find tales of men such as Red Kent, Sir Makin, Rike, Burlow and the Nuban, telling of their origins and the events that forged them. There is Jorg himself, striding the page as a child of six, as a teenage wanderer and as a young king. And then there is a tale about Prince Jalan Kendeth – liar, cheat, womaniser and coward.To the new reader, welcome to a lawless world where wit and sword are the most useful weapons, and danger lurks as much in candle-lit palaces as in dark alleys and dense woodland. To those who have already journeyed with Jorg, we hope you will enjoy renewing old acquaintances with your favourite characters.

Copyright (#ulink_793a1058-a521-518b-9047-1c4f8455d764)

HarperVoyager

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in ebook in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2017

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2017

Map © Andrew Ashton

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Jacket illustration © Kim Kincaid

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

These works are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in them are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008221386

Ebook Edition © September 2017 ISBN: 9780008221393

Version: 2017-10-04

Contents

Cover (#u5275d6b5-5575-5d0a-828f-b5033e2fc22c)

Title Page (#u359a4ab7-6b02-5bfa-8725-7271f921e49f)

Copyright (#u2bfb1eec-3169-5e48-9117-f44eb8068733)

Map (#u7b97de38-bfa2-5495-b091-447084a8e920)

Introduction (#uca301a20-1510-57c2-8ee8-c91333c8f85a)

A Rescue (#u424b43d3-9bea-5393-a774-6432f90f0352)

Sleeping Beauty (#ue9b54716-8c2d-536c-aa47-d9e2c0e1aa6c)

Bad Seed (#u53b0129c-4f7e-5b71-9411-fd6785d3da33)

The Nature of the Beast (#litres_trial_promo)

The Weight of Command (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Mode (#litres_trial_promo)

Mercy (#litres_trial_promo)

A Good Name (#litres_trial_promo)

Choices (#litres_trial_promo)

No other Troy (#litres_trial_promo)

The Secret (#litres_trial_promo)

Escape (#litres_trial_promo)

Know Thyself (#litres_trial_promo)

Three is the Charm (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mark Lawrence (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Map (#ulink_b3888a49-fe77-5d03-a508-49511e07ddda)

Introduction (#ulink_ce007b1d-7ba7-567b-b9f1-b57dc3e37069)

I learned most of what I know about writing from writing short stories. They’re a great place to practise the art. They are also a fine means by which to revisit a character or a world, illuminating a corner of the original tale that perhaps deserves more attention. In addition, they can be used to look back over the years, allowing us to see how our heroes and villains … well mainly villains if we’re honest … came to be where we found them and what shaped them along the way.

The stories in this anthology were written over the space of a few years, mostly for other projects. They offer a mix of murder, mayhem, pathos, and philosophy, and stand on their own without the need to have read the books that inspired them. The events occur before or around the edges of those described in the Broken Empire trilogy and will contain a variety of spoilers.

I hope you’ll enjoy dipping into the lives of Jorg and his brothers one more time. It was a grand tale and I was sorry to leave it behind.

Mark Lawrence

Bristol, 2017

Oh, and I’ve added a brief footnote at the end of each story … because I wanted to!

A Rescue (#ulink_5a03416c-c28f-5119-93af-a076c0f0d62f)

‘I spent a year hunting down the men who burned my home. I followed them across three nations.’

‘I see.’ The old man laid down his quill and looked up across the desk at Makin.

Makin returned the stare. The king’s man had a long white beard, no wider than his narrow chin and reaching down across his chest to coil on the desk before him. He’d asked no question but Makin felt the need to answer.

‘I wanted them to pay for the lives of my wife and my child.’ Even now the anger rose in him, a sharpness twitching his hands towards violence, a yammering in his ears that made him want to shout.

‘And did it help?’ Lundist studied him with dark eyes.

The guards had told Makin the man had journeyed from the Utter East and King Olidan had hired him to tutor his children, but it seemed his duties extended further than that.

‘Did it help?’ Makin tried to keep the snarl from his voice.

‘Yes.’ Lundist set his hands before him, the tips of his long fingers meeting in front of his chest. ‘Did taking your revenge ease your pain?’

‘No.’ When he took to his bed, when he closed his eyes, it was blue sky Makin saw, the blue line of sky he had watched from the ditch he had lain in, run through, bleeding out his lifeblood. A line of china blue fringed with grass and weeds, black against the brightness of the day. The voices would return to him – the harsh cries of the footmen set to chase down his household. The crackle of the flames finding the roof. Cerys hid from the fire as her mother had told her to. A brave girl, three years in the world. She hid well and no one found her, save the smoke, strangling her beneath her bed before the flames began their feast.

‘… your father.’

‘Your pardon?’ Makin became aware that Lundist was speaking again.

‘The captain of the guard accepted you for wall duty because I know your father has ties with the Ancrath family,’ Lundist said.

‘I thought the test …’

‘It was important to know that you can fight – and your sword skills are very impressive – but to serve within the castle there must be trust, and that means family. You are the third son of Arkland Bortha, Lord of Trent, a region that one might cover a fair portion of with the king’s tablecloth. You yourself are landless. A widower at one and twenty.’

‘I see.’ Makin nodded. He had disarmed four of Sir Grehem’s men when they came at him. Several sported large bruises the next day although the swords had been wooden.

‘The men don’t like you, Makin. Did you know that?’ Lundist peered up from the notes before him. ‘It is said that you are not an easy man to get along with.’

Makin forced the scowl from his face. ‘I used to be good at making friends.’

‘You are …’ Lundist traced the passage with his finger, ‘a difficult man, given to black moods, prone to violence.’

Makin shrugged. It wasn’t untrue. He wondered where he would go when Lundist dismissed him from the guard.

‘Fortunately,’ Lundist continued, ‘King Olidan considers such qualities to be a price worth paying to have in his employ men who excel at taking lives when he commands it, or in defence of what he owns. You’re to be put on general castle duty on a permanent basis.’

Makin pursed his lips, unsure of how he felt. Taking service with the king had seemed to be what he needed after his long and bloody year. Setting down roots again. Service, duty, renewed purpose, after his losses had set him adrift for so long. But just now, when he had thought himself cut loose once more, bound for the loneliness of the road, he had, for a moment, welcomed it.

Makin stood, pushing back the chair that Lundist had directed him to. ‘I will attempt to live up to the trust that’s been placed in me.’ He thought of the ditch. Cerys had had faith in him, a child’s blind faith. Nessa had had faith, in him, in his word, in God, in justice … and her trust had seen her pinned to the ground by a spear in the cornfield behind her home. He saw again the blue strip of sky.

Lundist bent to his ledger, quill scratching across parchment.

As Makin turned to go, the tutor spoke again. ‘The need for vengeance feels like a hunger, but there is no sating it. Instead it consumes the man that feeds it. Vengeance is taking from the world. The only cure is to give.’

Makin didn’t trust himself to speak and instead kept his jaw locked tight. What did a dried-up old scribe know of the hurts he’d suffered?

‘There’s a gap between youth and age that words can’t cross,’ Lundist said. He sounded sad. ‘Go in peace, Makin. Serve your king.’

‘The Healing Hall is on fire!’ A guardsman burst through the door into the barracks.

‘What?’ Makin rolled to his feet from the bunk, sword in his hand. He’d heard the man’s words. Saying ‘what’ was just a reflex, buying time to process the information. He glanced at the blade in his grasp. An edge would rarely help in fighting flames. ‘Are we under attack?’ No one would be mad enough to attack the Tall Castle, but on the other hand the queen and her two sons had been ambushed just a day from the capital. Only the older boy had survived, and barely.

‘The Healing Hall is on fire!’ The man repeated, looking around wildly. Makin recognized him as Aubrek, a new recruit: a big lad, second son of a landed knight and more used to village life than castles. ‘Fire!’ All along the barracks room men were tumbling from their beds, reaching for weapons.

Makin pushed past Aubrek and gazed out into the night. An orange glow lit the courtyard and on the far side tongues of flame flickered from the arched windows of the Healing Hall, licking the stonework above.

Castle-dwellers scurried in the shadows, shouts of alarm rang out, but the siege bell held its peace.

‘Fire!’ Makin roared. ‘Get buckets! Get to the East Well!’

Ignoring his own orders, Makin ran straight for the hall. It had once been the House of Or’s family church. When the Ancraths took the Tall Castle a hundred and twenty years previously they had built a second church, bigger and better, leaving the original for the treatment of the sick and injured. Or, more accurately, to repair their soldiers.

The heat brought Makin up short yards from the wall.

‘The Devil’s work!’ Friar Glenn’s voice just behind him.

Makin turned to see the squat friar, halted a few yards shy of his position, the firelight glaring on the baldness of his tonsure. ‘Is the boy in there?’

Friar Glenn stood, mesmerized by the flames. ‘Cleansed by fire …’

Makin grabbed him, taking two handfuls of his brown robe and heaving him to his toes. ‘The boy! Is Prince Jorg still in there?’ Last Makin heard the child had still been recuperating from the attack that had killed his mother and brother.

A wince of annoyance crossed the friar’s beatific expression. ‘He … may be.’

‘We need to get in there!’ The young prince had hidden in a hook-briar when the enemy had come for him a week earlier. He had sustained scores of deep wounds from the thorns and they had soured despite Friar Glenn’s frequent purging in the Healing Hall. He wouldn’t be getting out on his own.

‘The Devil’s in him: my prayers have made no impression on his fevers.’ The friar sank to his knees, hands clasped before him. ‘If God delivers Prince Jorg from the fire then—’

Makin took off, skirting around the building toward the small door at the rear that would once have given access to the choir loft. A nine-year-old boy in the grip of delirium would need more than prayers to escape the conflagration.

Cries rang out behind him but with the roar of the fire at the windows no meaning accompanied the shouts. Makin reached the door and took the iron handle, finding it hot in his grasp. At first it seemed that he was locked out, but with a roar of his own he heaved and found some give. The air sucked in through the gap he’d made, the flames within hungry for it. The door surrendered suddenly and a wind rushed past him into the old church. Smoke swirled in its wake, filling the corridor beyond.

Every animal fears fire. There are no exceptions. It’s death incarnate. Pain and death. And fear held Makin in the doorway, trapped there beneath the weight of it as the wind died around him. He didn’t know the boy. In the years Makin had served in King Olidan’s castle guard he had seen the young princes on maybe three occasions. It wasn’t his part to speak to them – merely to secure the perimeter. Yet here he stood now, at the hot heart of the matter.

Makin drew a breath and choked. No part of him wanted to venture inside. No one would condemn him for stepping back – and even if they did he had no friends within the castle, none whose opinion he cared about. Nothing bound him to his service but an empty promise and a vague sense of duty.

He took a step back. For a moment in place of swirling smoke he saw a line of brittle blue sky. Come morning this place would be blackened spars, fallen walls. Years ago, when they had lifted him from that ditch, more dead than alive, they had carried him past the ruins of his home. He hadn’t known then that Cerys lay within, beneath soot-black stones and stinking char.

Somehow Makin found himself inside the building, the air hot, suffocating, and thick with smoke around him. He couldn’t remember deciding to enter. Bent double he found he could just about breathe beneath the worst of the smoke, and with stinging, streaming eyes he staggered on.

A short corridor brought him to the great hall. Here the belly of the smoke lay higher, a dark and roiling ceiling that he would have to reach up to touch. Flames scaled the walls wherever a tapestry or panelling gave them a path. The crackling roar deafened him, the heat taking the tears from his eyes. A tapestry behind him, that had been smouldering when he passed it, burst into bright flames all along its length.

A number of pallets for the sick lined the room, many askew or overturned. Makin tried to draw breath to call for the prince but the air scorched his lungs and left him gasping. A moment later he was on his knees, though he had no intention to fall. ‘Prince Jorg …’ a whisper.

The heat pressed him to the flagstones like a great hand, sapping the strength from him, leaving each muscle limp. Makin knew that he would die there. ‘Cerys.’ His lips framed her name and he saw her, running through the meadow, blonde, mischievous, beautiful beyond any words at his disposal. For the first time in forever the vision wasn’t razor-edged with sorrow.

With his cheek pressed to the stone floor Makin saw the prince, also on the ground. Over by the great hearth one of the heaps of bedding from the fallen pallets had a face among its folds.

Makin crawled, the hands he put before him blistered and red. One bundle, missed in the smoke, proved to be a man, the friar’s muscular orderly, a fellow named Inch. A burning timber had fallen from above and blazed across his arm. The boy looked no more alive: white-faced, eyes closed, but the fire had no part of him. Makin snagged the boy’s leg and hauled him back across the hall.

Pulling the nine-year-old felt harder than dragging a fallen stallion. Makin gasped and scrabbled for purchase on the stones. The smoke ceiling now held just a few feet above the floor, dark and hot and murderous.

‘I …’ Makin heaved the boy and himself another yard. ‘Can’t …’ He slumped against the floor. Even the roar of the fire seemed distant now. If only the heat would let up he could sleep.

He felt them rather than saw them. Their presence to either side of him, luminous through the smoke. Nessa and Cerys, hands joined above him. He felt them as he had not since the day they died. Both had been absent from the burial. Cerys wasn’t there as her little casket of ash and bone was lowered, lily-covered into the cold ground. Nessa didn’t hear the choir sing for her, though Makin had paid their passage from Everan and selected her favourite hymns. Neither of them had watched when he killed the men who had led the assault. Those killings had left him dirty, further away from the lives he’d sought revenge for. Now though, both Nessa and Cerys stood beside him, silent, but watching, lending him strength.

‘They tell me you were black and smoking when you crawled from the Healing Hall.’ King Olidan watched Makin from his throne, eyes wintry beneath an iron crown.

‘I have no memory of it, highness.’ Makin’s first memory was of coughing his guts up in the barracks, with the burns across his back an agony beyond believing. The prince had been taken into Friar Glen’s care once more, hours earlier.

‘My son has no memory of it either,’ the king said. ‘He escaped the friar’s watch and ran for the woods, still delirious. Father Gomst says the prince’s fever broke some days after his recapture.’

‘I’m glad of it, highness.’ Makin tried not to move his shoulders despite the ache of his scars, only now ceasing to weep after weeks of healing.

‘It is my wish that Prince Jorg remain ignorant of your role, Makin.’

‘Yes, highness.’ Makin nodded.

‘I should say, Sir Makin.’ The king rose from his throne and descended the dais, footsteps echoing beneath the low ceiling of his throne room. ‘You are to be one of my table knights. Recognition of the risks you took in saving my son.’

‘My thanks, highness.’ Makin bowed his head.

‘Sir Grehem tells me you are a changed man, Sir Makin. The castle guard have taken you to their hearts. He says that you have many friends among them …’ King Olidan stood behind him, footsteps silent for a moment. ‘My son does not need friends, Sir Makin. He does not need to think he will be saved should ill befall him. He does not need debts.’ The king walked around Makin, his steps slow and even. They were of a height, both tall, both strong, the king a decade older. ‘Young Jorg burns around the hurt he has taken. He burns for revenge. It’s this singularity of purpose that a king requires, that my house has always nurtured. Thrones are not won by the weak. They are not kept except by men who are hard, cold, focused.’ King Olidan came front and centre once more, holding Makin’s gaze – and in his eyes Makin found more to fear than he had in the jaws of the fire. ‘Do we understand each other, Sir Makin?’

‘Yes, highness.’ Makin looked away.

‘You may go. See Sir Grehem about your new duties.’

‘Yes, highness.’ And Makin turned on his heel, starting the long retreat to the great doors.

He walked the whole way with the weight of King Olidan’s regard upon him. Once the doors were closed behind him, once he had walked to the grand stair, only then did Makin speak the words he couldn’t say to Olidan, words the king would never hear, however loud-spoken. ‘I didn’t save your son. He saved me.’

Returning to his duties, Makin knew that however long the child pursued his vengeance it would never fill him, never heal the wounds he had taken. The prince might grow to be as cold and dangerous as his father, but Makin would guard him, give him the time he needed, because in the end nothing would save the boy except his own moment in the doorway, with his own fire ahead and his own cowardice behind. Makin could tell him that of course – but there are many gaps in this world … and there are some that words can’t cross.

Footnote

Makin has always been an interesting character for me, a failed father-figure if you like. He should be Jorg’s moral touchstone but too often finds himself swept along by the force of Jorg’s personality and by the chaos/cruelty of the life he’s entangled in. We root for him to recover himself.

Sleeping Beauty (#ulink_954c6414-524d-5de6-95c4-da36240acec9)

A kiss woke me. A cool kiss pulled me from the hot depths of my dreaming. Lips touched mine, and deep as I was, dark as I was, I knew her, and let her lead me.

‘Katherine?’ I spoke her name but made no sound. A whiteness left me blind. I closed my eyes just to see the dark. ‘Katherine?’ A whisper this time. Damn but my throat hurt.

I turned my head, finding it a ponderous thing, as if my muscles strove to turn the world around me whilst I remained without motion. A white ceiling rotated into white walls. A steel surface came into view, gleaming and stainless.

Now I knew something beyond her name. I knew white walls and a steel table. Where I was, who I was, were things yet to be discovered.

Jorg. The name felt right. It fitted my mouth and my person. Hard and direct.

I could see a sprawl of long black hair spread across the shining table, reaching from beneath my cheek, overhanging the edge. Had Katherine climbed it to deliver her kiss? My vision swam, my thoughts with it – was I drunk … or worse? I didn’t feel myself – I might not yet know who I was, but I knew enough to say that.

Images came and went, replacing the room. Names floated up from the back of my mind. Vyene. I had a barber cut my hair almost to the scalp when I left Vyene. I remembered the snip of his shears and the dark heap of my locks, tumbled across his tiled floor. Hakon had mocked me when I emerged cold-headed into the autumn chill.

Hakon? I tried to hang details upon the void beneath his name. Tall, lean … no more than twenty, his beard short and bound tight by an iron ring beneath his chin. ‘Jorg the Bald!’ he’d greeted me and fanned out his own golden mane across his shoulders, bright against wolfskins.

‘Watch your mouth.’ I’d said it without rancour. These Norse have little enough respect for royalty. Mind you neither do I. ‘Has my beauty fled me?’ I mocked sorrow. ‘Sometimes you have to make sacrifices in war, Hakon. I surrendered my lovely locks. Then I watched them burn. In the battle of man against lice I am the victor, whilst you, my friend, still crawl. I sacrificed one beauty for another. My own, in exchange for the cries of my enemies. They died by the thousand, in the fire.’

‘Lice don’t scream. They pop.’

I recalled the bristling of scalp beneath palm as I rubbed my head trying to find an answer to that one. I tried now to touch the hair spread out before me across the steel but found my hands restrained. I made to sit up but a strap across my chest held me down. Straining, I could see five more straps binding me to the table, running across my chest, stomach, hips, legs, and ankles. I wore nothing else. Tubes ran from glass bottles on a stand above me, down into the veins of my left wrist.

This room, this white and windowless chamber, had not been made by any people of the Broken Empire. No smith could have fashioned the table, and the plasteek tubes lay beyond the art of some king’s alchemist. I had woken out of time, led by dreams and a kiss to some den of the Builders.

The kiss! I flung my head to the other side, half-expecting to find Katherine standing there, silent beside the table. But no – only sterile white walls. Her scent lingered though. White musk, fainter than faint, but more real than dream.

Me, a table, a simple room of harsh angles, kept warm and light by some invisible artifice. The warmth enfolded me. My last memories had been of cold. Hakon and me trudging through the snow-bound forests of eastern Slov, a week out from Vyene. We picked our path between the pines where the ground lay clearest, leading our horses. Both of us huddled in our furs, me with only a hood and a quarter inch of hair to keep my head from freezing. Winter had fallen upon us, hard, early, and unannounced.

‘It’s buggery cold,’ I said unnecessarily, letting my breath plume before me.

‘Ha! In the true north we’d call this a valley spring.’ Hakon, frost in his beard, hands buried in leather mittens lined with fur.

‘Yes?’ I pushed through the pine branches, hearing them snap and the frost scatter down. ‘Then how come you look as cold as I feel?’

‘Ah.’ A grin cracked his wind-reddened cheeks. ‘In the north we stay by the hearth until summer.’

‘We should have stayed by that last hearth then.’ I floundered through snow, banked along a break in the trees.

‘I didn’t like the company.’

I had no answer for that. Exhaustion had its teeth in me and my bones lay cold in white flesh.

The house in question had stood implausibly deep in the forest, so isolated that Hakon had been convinced the tales of a witch were true.

‘Don’t be stupid,’ I’d told him. ‘If there’s a witch living in the forest and she eats children then she’s going to want to live on the edge, isn’t she? I mean how often does a little Gerta or Hans come wandering this far in?’

Hakon had caved beneath the undeniable weight of my logic. We’d gone to ask for shelter, and failing it being offered, to take it. The door stood ajar – never a good sign in a winter storm, and the snow in front of the porch lay heavily trodden, covered with a fresh fall that obscured detail.

‘Something’s not right.’ Hakon unslung his axe, a heavy, single-bladed thing with a long cutting edge, curved to bite deeper.

I’d nodded and advanced, silent save for the crump of fresh snow beneath my boots. Reaching out with my sword, I pushed the door wider. My theory about little girls and the middle of forests didn’t survive the hallway. A child lay sprawled there, golden curls splashed with crimson, arms and legs at broken angles. I advanced another step, my nose wrinkled against the stink. Blood, the reek of guts, and something else, something rank and feral.

A hand clamped my shoulder and I nearly spun to hack it off. ‘What?’

‘We should leave … the witch—’

‘There’s no witch living here.’ I pointed at the corpse. ‘Unless she’s got teeth big enough to bite a girl’s face off, a taste for entrails, and a nasty habit of shitting in her own hallway.’ I pointed to the brown mound by the foot of the stairs, which, unlike the girl’s guts, was still steaming ever so slightly.

‘Bear!’ Hakon released my shoulder and started to back away. ‘Let’s run.’

‘Let’s,’ I agreed.

A big black head thrust out from beneath the stairs as we retreated to the horses. I saw another bear, larger still, through the broken shutters to the side of the house, licking out a bowl in the kitchen. And, as we reached our steeds and started to hurry away, a cub watched us from the attic bedroom, its wet muzzle thrust out between the winter boarding, teeth scarlet.

Why did it have to be bears? If it had been a witch I’d have stuck my sword through her neck and moved in. Bears though … Better to run, even if it’s out into the killing cold.

Each step sapped my strength as the heat left me, stolen a scrap at a time, squandered into the night air with every breath.

I plodded on, deep in myself, refusing exhaustion. It had been time to leave Vyene, whether winter was approaching or not. I might regret it now, freezing in the pathless forest, but I’d stayed too long. Sometimes the dream of a place sucks you in and before you know it you’re part of that dream too. In a city as grand and as old as Vyene the dream is one of glory, steeped in history, but like all dreams it’s an illusion that will use you up while grass grows under your feet, while thorns spring up, dense on all sides, and hem you in. A kiss had woken me there too. Elin, leaving with her brother, Sindri, to their halls and duties in the north. Hakon had wanted to stay, but he’d had enough of the ancient capital and wanted to see the provinces, to slum it with the King of Renar. And so we’d left, escaped the trap of intrigue and politicking that was Vyene, shook ourselves free before its soft jaws closed entirely around us, and moved along.

Full night and a bitter moon found us some miles further on, breaking from the treeline and setting out across a snowfield where the land turned stony and started to rise. Snow began to fall once more, large-flaked, ghostly, ponderous at first, then rushing as the wind picked up again.

I lay on the steel table remembering – seeing lost days unfold. The dreams that had wrapped me still clung, leeching away urgency and care. It occurred to me that some drug pulsed in my veins, some sleeping draught to keep me dull. I jerked my body within the bands that kept me on the table. Nothing moved. The thing must be bolted to the floor.

Each strap had a buckle. One free hand and I’d be out of there. So all that truly held me was the binding on my wrists. I strained to break a hand free but the bands weren’t made for breaking.

‘Fuck.’

I stared around the room. In the top corner, opposite me, a glass eye watched, a short black cylinder ending in a dark lens.

The tubes that ran, from bottles on a steel stand to needles in my arm, hung tantalisingly close. Straining until my neck screamed and my vision blurred, I could almost touch the nearest of the trio with the tip of my tongue. Close! But ‘close’ can be the difference between cutting a throat and slicing air.

I stared at the tubes, hating them, trying not to let the drugs drag me down again. I felt myself sinking, the whiteness of the ceiling filling my mind.

Sinking.

I had felt myself sinking into a white embrace when we left the trees behind. The snow crust lay too thin to hold my weight and beneath it, cold soft depths where a man could flounder. In the drifts a man would lose the last of his heat quick enough, and find at the limits of his strength that the snow became almost warm, a cradle into which he might relax, and perhaps sleep, just for a moment, to recover himself.

‘Here!’ Hakon held the haft of his axe for me to grab hold and hauled me onto firmer ground.

‘Why did we leave the woods, again?’ I asked the question with numb lips, the words coming out blunt-edged. At least my teeth had ceased to chatter, which seemed as if it should be a good thing. The wind scoured the hillside. In the forest the trees had muted it.

‘Nothing beats a cave for shelter.’ Hakon pushed me on.

‘Cave? Where?’ I could see little past swirling snow and darkness.

I’d promised Sindri to send his cousin back alive after his trip to Renar. So far it looked as though it was Hakon keeping me alive. ‘And where’s my damn horse?’

‘Back in the trees with mine. I saw a light. We’re checking it out. You’ll remember when you’re warmer. Let’s get to the cave.’ Hakon kept up a steady pace and I stumbled after him.

‘Cave? There’ll be bears!’ I remembered something about a baby bear with a red muzzle, and a girl with golden locks and no face. Swords and axes aren’t a match for a bear’s strength. Put a length of steel through one and the beast will still kill you before it realizes it’s dead.

‘Bears don’t carry lanterns.’ Hakon scrambled up a boulder. ‘There! I see it. A light.’ He slid back down. ‘Doesn’t look like a fire though.’ A note of concern creeping in amid the excitement.

‘Hell if I care.’ I pushed past him, weaving a path up the slope.

In the end he followed. What choice was there other than to freeze to death? The bitter weather had come on us unexpectedly, a vicious early bite of winter at the tail of a mild autumn.

It’s the simple things often as not that lay us low. It’s the everyday world intruding on our little dreams of power and glory that kills us. For all my cunning and deathly swordplay a prince of Ancrath could die coughing up the flu, or choking on a fishbone, or frozen on a lonely slope by a freak snowstorm, same as any other man.

The light and the promised cave both came into view over the next rise. The sight arrested me. The light burned at the back of a yawning cavern but as we approached a second glow began to spread across the slope ahead of us. A luminous mist. The spirit rose from the ground as a swimmer breaks the surface of a river. She moved across the snow-covered rocks. Back and forth before the cave mouth, illumination bleeding from each line, her face a death mask, jawbone gaping. She drifted closer, straggles of pale hair and tatters of dress unmoving despite the wind that tore across the hillside. The snow lit beneath her, each curious lump and bump of it commanding black shadows, revolving to point away from the spirit as she moved, as if indicating the many directions in which we might flee.

I felt Hakon shift behind me, turning to run. ‘Stay,’ I told him. ‘I’ve met ghosts before. None of them with a bite meaner than their bark.’

The white skull tilted on its vertebrae, cocked to the side whilst the empty orbits considered me. ‘Better run, boy. Death waits inside.’ Her voice was a cracked thing that set my teeth on edge.

‘No,’ I said.

‘My curse is on you.’ A bony digit marked me out as her target. Madness wavered in her words, and strain, as if each utterance were gasped out past some unbearable agony. ‘Run and you might outpace it.’

‘I’m too tired to run, ghost. I’m going inside.’

She drifted closer still, surrounding me with a light that held no whisper of warmth. ‘Needles and death, boy, there’s nothing in there for you, just needles and death.’ A gasp.

Something about being threatened lit a fire in my belly and, although the cold seemed all the more bitter for it, I felt more myself.

‘Needles? Might I prick myself on one? That’s probably the silliest curse I’ve heard in a long while – and men are seldom eloquent when sliding off my sword so I’ve heard some stupid curses in my time.’

‘Fool!’ The phantom’s voice built to a piercing shriek, the glow of her bones growing more fierce by the second. ‘Run while you—’ And just as swiftly she was gone, torn to shreds on the wind, her light extinguished.

I stood for a long moment, blind, pinched by the gale’s icy fingers. The moon peered through a wind-torn rip amid the cloudbanks and found the slope again before either of us moved to speak.

‘Well,’ I said. ‘That was unusual.’

‘Odin keep us.’ Hakon’s wisdom on the subject.

‘He’s as likely to keep us as the White Christ is.’ I had no bone to pick with heathen bone-pickers. One god or many, none of them ever seemed to like us much. ‘What did she think to terrify us with? Needles?’ I started in toward the cave.

‘What are you doing?’ Hakon caught my arm. ‘She said we’d die.’

I knew Norsemen took their evil spirits seriously but I hadn’t expected one deranged ghost to unman my axe-wielding barbarian so much. ‘If we see a needle we’ll avoid jabbing ourselves with it. How about that? We’ll go around.’ I drew my sword and waved him on. ‘Does she have some demonic sewing kit in there? Will the thread assault us? The thimbles hurl themselves upon me? Bobbins—’

‘She said—’

‘We’ll die. I know. And what will we do out here?’ Something tugged at my foot as I made to take another step. I crouched and brushed at the snow and my hand came away dark with blood though I’d felt no bite. A gleaming coil of wire lay exposed, emerging from the stony ground, covered in thin blades sharp as razors. Hakon crouched beside me to look.

The wire was a thing of the Builders. None today could make such steel and have it sitting out in the wilds, still sharp, untouched by rust. I looked at the blood blotting into my wrappings then eyed the uneven terrain with new suspicion. The Builders made their own ghosts too – not echoes of emotion or shadows of despair such as men of our time might leave behind, but constructs built of data and light, powered by dry machinery where cogs turned and numbers danced. I mistrusted such monstrosities more than mere phantoms.

‘Perhaps we should build a windbreak among the trees,’ I said. ‘Try the tinderbox again and, if we can get a flame, build a fire big enough to put a boat-burning to shame.’

As I spoke the snow where the ghost had fallen apart began to glow and a second spirit rose through it, taking all the light for herself. There could be no confusing this one with the departed curse-maker. Mouldering bones and a death’s head grin had been replaced with alabaster limbs spun about with gossamer, her face ivory perfection, all compassion and kind eyes.

‘The cave is warm and safe.’ Golden tones pulsating through the light. ‘A place of sanctuary against the night. My sister’s madness does not rule there – though her curse lingers. I can’t break it but I can bend it. Even if a needle should prick you, you won’t die, only sleep a while.’

I made a courtly bow, there on the hill in the teeth of the gale and on the edge of my endurance. ‘Sleep sounds fine and good, but if it’s all the same to you, fair spirit, I’d rather slumber on my own terms.’ I held my hand and its red bandages out toward her. ‘Without needles. I’ve bled enough tonight already.’

‘If you see a needle … go around.’ She offered her suggestion with a hint of a smile and vanished, not breaking apart as the sister did but fading like a footprint on wet sand where the waves wash. I hesitated still but the thought of warmth pulled at me.

‘Come on.’ And I led the way forward, placing each foot with care and encountering no more razored wire.

Inside the cave the wind fell away within the space of three steps. It still shrieked and moaned outside but, where we stood, the dry flakes could manage no more than a lazy swirl about our boots. My ears rang with the near-silence after so long filled with that relentless howl, and almost immediately my head began to ache and my body burn. Pain is life’s signature. Sheltered at last, we stopped dying and started to hurt.

I returned to myself as if rising from the depths, reaching for a distant surface. The white ceiling greeted me. The table, the tubes, the straps. How long had I dreamed? Was Katherine still here or had her kiss grown cold upon my lips?

I thrashed in my bonds, sacrificing any shred of pride against a remote chance of escape. I stopped moments later, sweaty and with my hair strewn across my face. I spat out black strands and looked at those tubes and the clear liquids within. The drugs still pulsed in my veins, waiting to drag me back into sleep.

Flinging my hair back from my face, I banged my head against the table. ‘Fuck.’ It hurt and the dull clank might alert my captors but even so, I did it again, the other way this time, slinging the length of my locks back across my face and raising my head until the bones in my neck screamed.

It took seven attempts but finally my hair draped the bundled tubes and at the utmost lunge I caught some of the spare ends between my front teeth, ensnaring the whole bundle. I pulled down and, with my head against the table managed to get my teeth around one of the tubes itself.

In the ceiling corner a small red light began to wink above the glass eye that watched me.

It took several moments to feed the tubes through my teeth until they made a taut line to my wrist. I paused one time at a distant noise, a mechanical clunking that sounded once, twice, and fell silent.

With the tubes tight in my mouth, I shot a venomous look toward the watching eye and jerked my head. A sharp pain flared in my wrist as the needles tore free, followed by a dull ache and wetness – blood? Liquid from the tubes?

I started to pull my hand free. The pain of ripping the tubes clear proved nothing next to the agony that followed. It helped to think that if I didn’t escape then endless torments might be heaped on me whilst I lay trapped.

The hand is made of many little bones. I’ve seen them often enough, exposed in cut flesh or revealed by rot. With sufficient pressure these bones give. They will rearrange and, if necessary, crack, but there are no constraints the size of a wrist that will prevent a hand from being drawn through them … if you are prepared to pay the price.

My hand came free with a snap. The cost of freedom included broken bones, considerable lost skin, and agony. Without the lubrication from the fluids that had spilled out as the tubes came free, and my own blood, the price would have been steeper. Even so, my sword hand would not be fit to hold a sword for quite some while.

A loud clang, closer than before. A metal door opening.

On the stand that held the vials and tubes red lights began to blink and a high-pitched call rang out like the cry of some alien bird, repeating again and again.

Undoing tightly buckled straps with a broken hand and slippery fingers is difficult. Doing it fast, expecting at any second to hear the approach of footsteps, is still more difficult. In an ecstasy of fumbling I managed to get my other wrist unbound, cursing in pain and frustration.

The door that opened was not the one I imagined to lie somewhere behind my head but a small and thus far unsuspected hatch high in the wall to my left. The thing that emerged from the darkness behind the little door had too many legs, possibly ten, all gleaming silver and cunningly articulated. A bulbous glass ovoid comprised the bulk of its insectoid body, and within it a red liquid sloshed. Where the creature’s mouthparts should have been a single long needle protruded.

I started to unbuckle the first and topmost of the six belts holding me flat against the table.

The darkness of the cave mouth had been less profound than that of the night outside. A light had burned at the back of it. Hakon and I edged in deeper, axe and sword gripped in frozen hands.

The light still blinked and now we saw that it sat beneath the legend ‘Bunker 17’ and above a rectangular doorway set into the back of the cavern.

‘A Builder light.’ The cold circle of illumination had no hint of flame about it.

Hakon made a slow rotation, checking the shadowed margins. I glanced back at the falling snow, lit by the glow of the Builders’ light. White legions racing silent across the cave mouth. I wondered at the ghosts we’d seen. Spirits of those who failed to do correctly that last thing anyone ever has to, and die properly, or something older still … the minds of long-dead Builders trapped within their machinery and projected in some game of puppetry and shadow. I’d met both kinds before and had thought these ones to be true ghosts, but now my suspicions grew.

‘We should stay here,’ I said, turning and stepping away from the doorway.

As I did so a wave of warm air followed me, thick with the scent of roasting meat. I turned back to face the corridor leading away into the hill. ‘It’s a trap. And not a subtle one.’

‘In the north we take what we need.’ Hakon lifted his axe and advanced, already swallowing as the juices ran in his mouth.

My stomach rumbled. With a shrug I followed him in. ‘We do that in the south too.’

Lights went on ahead of us down the length of the corridor. Maybe one in seven of the white glass discs on the ceiling still worked but together they provided better illumination than any torch or lantern.

Fifty yards on and a heavy steel door blocked the way, but only partially. The thickness of it lay curled around the force of some unimaginable blow and it stood propped against the frame, heavier than an armoured warhorse but with room to slide past. Just beyond, through the gap, I could see a gleaming and many-legged insect, silver in the ancient light, needle-mouthed, its body a clear chamber filled with red venom.

‘I’ve seen the needle,’ I said, not turning away. ‘Going around might be difficult …’ I kept my eye on it against the possibility it might scuttle forward and sting me through my boot. ‘But I think if I beat it with my sword the problem should go away.’ It’s a technique that works on a lot of problems.

‘Uh,’ said Hakon. Not exactly the encouragement I’d been hoping for but I shrugged it off.

‘You hold the door. I’ll go through and stick it.’

‘Uh.’ Followed by the clatter of axe hitting floor.

I turned to see Hakon sprawled, five of the metal insects on his back, their needles deep in his flesh.

‘Shh—’ Something small and sharp stabbed me in the hollow of my back, ‘—it!’ I spun, trying to dislodge the thing but it clung with a dozen clawed feet. Warmth spread up my spine. ‘Bastard!’ I threw myself back, crushing the thing against the door. Others scurried out from little hatches in the wall beside the door. The ones on Hakon withdrew their needles and scuttled toward me.

I wrecked several with my sword, shearing off legs and shattering bodies but I went down with needles in my thigh, hip and foot before I got them all, my strength flowing away like water from a broken gourd.

‘I remember you, you little bastard!’ I snarled it at the needle-bug as it descended from the now-invisible hatch. My hope that it might not be able to scale the table waned somewhat at seeing its speed over the smoothness of the wall.

The first of the six bands came loose and I started on the next. The dry click of metal feet reached me as the insect vanished beneath the table. For all I knew there were holes under my back through which it could stick me. I worked on, fingers slipping across the next buckle. If the thing had any intelligence behind it, it would come up out of reach by my feet.

The click of small claws against the steel leg of the table told me it was climbing the far end. The thing must have lodestones for claws: no creature the size of a rabbit could find purchase on the metal otherwise.

I freed the second band and started on the third … paused … looked about. Two silver legs hooked over the far end of the table. I leaned back and reached out for the stand holding the drug flasks, their tubes hanging loose now, contents leaking upon the floor. The needle-bug pulled itself over the lip of the table with a quickness that made my skin crawl. It turned its head toward my bound calf, needle pointing, a bead of clear liquid glistening at its tip … And with a roar I hauled the stand overhead, lifting it as far as the bands allowed, and crashed the haft of it into the needle-bug’s glassy body. Fragments flew everywhere and the twitching carcass slithered over the edge, landing with a brittle crunch.

With feverish concentration I unbuckled the remaining straps, scanning the walls as I did so for the arrival of more needle-bugs.

A minute later I set two bare feet to the cold floor and found my legs reluctant to take the weight of me, skinny as I was. Blood still dribbled from my wrist where the tubes had fed their filth into me. Skin flapped, raw flesh glistened.

The table lay bare save for some clear and squidgy pads that must have kept it from wearing sores into my back. A vent ran the length of it and a drain below. They must have sluiced away my filth as I lay unconscious. A pure hatred ran through me. I would hurt whoever did this to me, and then I would end them.

A door stood behind me, silvery-steel like the table. I looked about for weapons but the room was bare save for the corroded carcasses of ancient machinery. Gripping the drug stand like a spear, I advanced on the door. There would be larger foes outside. The bugs hadn’t lifted me onto the table or buckled me down.

I stood with a hand to the door for a moment, trying to clear my head. Had Katherine truly been here? Had she wakened me? A kiss seemed unlikely – the princess hated me, and with good reason. A knife to the heart seemed a more realistic greeting. Even so, something had woken me from what must be months of slumber, years even. And Katherine had once kept the company of a dream-witch, so why not her? Perhaps she thought letting me sleep my days away here, safe from nightmares, was too kind an end for me.

Remembering that I was watched, I left the door and stood before the eye peeping at me from the high corner with its little red light flashing.

‘I’m coming for you and death will not hide you.’ I swung the stand at arms’ length, smashing the box from its stand. It hit the wall, then the floor, and when the lens rolled free I crushed it beneath the stand’s metal foot. A grand speech perhaps for a man with no clothes, no weapon, and no plan, but it lit my fire and it never hurts to sow the seeds of unease in your foe’s mind.

The destruction of Builder machines is of course a terrible waste of knowledge and wonder beyond our imagination. There is, however, an undeniable thrill in doing it.

The door opened for me, the locking mechanism corroded, the metal degenerating into curious white powder – a good thing as I would not have been able to force it. The most surprising thing about the works of the Builders is always not how broken they are but just how many of them still function. After the slow passage of the eleven centuries since the Day of a Thousand Suns I would have expected them all to be dust. Certainly nothing built in the first three hundred years to follow that conflagration now survives.

The corridor beyond lay thick with dust, the corpse of a needle-bug disarticulated and strewn along the margins. Stairways led left and right, both blocked with rubble, the ceiling collapsed. I advanced further, to a point where a door opened to either side. To the left a domed steel machine glowing gently through small portals. Dozens of needle-bugs and others of similar design – but with cutting wheels or opposing thread-laced jaws in place of the needle – scattered the floor, most in pieces. The least damaged of them huddled close to the dome as if seeking sustenance from it. Several twitched towards me as I looked in, but none made it more than half way before the light died from their eyes and they ceased to move.

To the right, a room that radiated cold and contained several large chests, white, rectangular and without ornament or lock. Goosebumps rose across me as I entered the room. Perhaps just from the cold. It’s hard to be naked in a place that wants to hurt you. A layer of cloth would offer me little protection but I would have felt far more brave. I read in Tacitus that the Romans when they came to the Drowned Isles faced Brettan men who charged them wearing nothing but blue dye. The Brettans died in droves and surrendered their lands, but I can respect their courage, if not their methods.

A steel cylinder, thicker than my arm and half as long, stood between the chests. A long strap of dark and woven plasteek ran from top to bottom. I picked it up: heavier than I imagined. The legend stamped upon it was in no alphabet I recognized. I slung it over my shoulder. A looter decides on worth once he’s out.

I raised the lid of one of the chests using the metal stand. Freezing mist escaped with a soft sigh. The space within lay filled with frost, and with organs wrapped in clear plasteek: hearts, livers, eyeballs in jelly, and other pieces of man-tripe beyond my vocabulary. A second chest held glass vials bound top and bottom with metal rings and stamped with the plague symbol – triple intersecting crescent moons. This I knew from a weapons vault I once set on fire beneath Mount Honas.

I reached in and took three vials at random, so cold they stuck to my flesh. I put them on the ground, tearing skin to be free of them, then bound each with the plasteek tubes to the foot of the stand. I didn’t know what plague they might contain nor whether it was still virulent but when the only weapon you have is an awkward metal stick sporting blunt hooks you take whatever you find.

Turning to leave, I found the spirit in the doorway: Miss Kind-Eyes-and-Compassion, flickering now like the Builder-ghost I’d seen nearly a year earlier, and wearing a long white coat, almost a robe but without fold or style.

‘You should put those back, Jorg.’ She pointed to the vials at the end of my stand.

‘How do you know my name?’ I walked toward her.

‘I know a lot of things about you, J—’

I walked through her into the corridor. Often as not conversation is a delaying tactic and I’d waited long enough on that table.

‘—org. I know what is written in your blood. I could remake you whole from the smallest flake of your skin.’

‘Interesting,’ I said. ‘Where’s Hakon?’

I came to a large door at the end of the corridor. Locked.

‘You should listen carefully, Jorg. It’s difficult to maintain this projection so far from—’

‘Your name, ghost.’

‘Kalla Lefarge. I—’

‘Open this door, Kalla.’

‘You must understand, Jorg, mechanisms have finite duration. I need biological units to carry out my work. To carry me even. Projection has its lim—’

‘Now,’ I said, and banged the vials against the metal.

‘Don’t!’ She held out a hand as if that might stop me. The very first thing she said to me was to put them down. It pays to notice priorities. She’d said it as if they were of no great importance … but she said it first.

‘Or what?’ I clonked the end of the stand against the door again and the vials clinked together.

‘If a class alpha viral strain contaminates this facility it will be purged. I can neither override that protocol nor allow it to happen.’

A flicker of concern over those perfect features. Builder-ghosts were woven from the story of a person’s life – every detail – extrapolated from a billion seconds of scrutiny. This one I felt had drifted far from its template, but not so far it couldn’t still know fear.

‘Purged?’

‘With fire.’ Kalla’s face flickered briefly to a look of horror, returning to its customary serenity a moment later. I wondered from what instant that look had been stolen and what had set it on the face of the real Kalla – flesh and blood and bone like me, dust these many centuries. Had the creature before me grown far from its roots or had Kalla shared this madness? ‘Enough fire to leave these halls hollow and smoking.’

‘Better open the fucking door then.’ And I banged the stand in earnest.

‘Careful!’ A hand flew to her mouth. ‘There! It’s open!’

The hall beyond lay crossed with shadow and lit by irregular patches of light bright enough to make me squint. Steel tables lined each wall. A stench of rot filled my nose, along with something sharp, astringent, chemical. Corpses lay on every table. Some in pieces. Some fresh. Some corrupt. Organs floated in glass tubes running from ceiling to floor, threaded with bubbles – hearts, livers, lengths of gut. Behind the table closest to me a metal skeleton, or some close approximation, leaned across yet another corpse. Despite lacking muscle or flesh the thing moved, the cleverly articulated fingers of one hand swiftly driving the needle of a drug-vial into vital spots all across the cadaver before it. The other hand moved from unstrapping the remains to depressing raised bumps on certain mechanisms that replaced sections of the body such as the elbow joints. It finished by turning a dial on some engine sunk deep into the chest cavity.

I held the stand out between us, vials clinking, ready to fend the thing off if it jumped me.

‘This is the last of my medical units,’ the ghost said, voice wavering between two pitches as if unable to settle. ‘I’d ask you not to damage it further.’

As the skeleton straightened to regard me with black eyes bedded in silver-steel sockets, I noted across its bones the white powdery corrosion that I’d seen back on the lock to my sleeping chamber. The thing stepped away from the table, favouring one leg, a gritty sound accompanying each movement of its limbs. Only the nimble fingers seemed unaffected by the passage of a millennium.

The corpse, on the other hand, moved with far more surety and only the slightest whine of mechanics as it sat up between us.

‘Hakon.’

They’d done something to his eyes, rods of glass and metal jutting from red sockets; his hair and beard had been shaved away, but his smile was the same.

In my moment of hesitation Hakon, or his remains, took hold of the stand. I tugged at it but his grip had no give.

‘This one nearly succeeded,’ he said. Or rather it was the ghost’s voice, but firmer, and sounding from the box in his chest. ‘He can support me, but his brain degenerates under fine control and the degree of putrefaction about the implants is too great to be sustained in the longer term.’

‘And I was to be your next … steed?’ I tugged at the stand again.

‘You still will be,’ Kalla said, her voice coming distractingly from both the ghost and the box in Hakon’s chest. ‘The last faults have been analysed. This time it will succeed. Nor will your life be forfeit. Even this one isn’t dead – not truly.’ Hakon slipped from the table and stood before me, both hands tight about the stand. ‘Carry me for long enough to complete three alternate hosts and I’ll send you on your way with nothing but a few stitches.’

‘Why me?’ I glanced around, looking for the way out. ‘Get some new bodies to play with.’

‘You’ve broken my last sedation units.’

‘Mend them—’ I lunged forward and tore one of the vials free.

Releasing the stand, I stepped away, holding the vial overhead, ready to smash it.

‘Don’t—’

‘Who was the other one? The ghost who put on the skull-and-bones show for us, tried to scare us off?’

‘A colleague at this facility, also copied and stored as a data echo. She … disapproves of my work here. We’re isolated in this network. Security they called it.’ She made a bitter noise. ‘Our research too classified to risk a leak. And so until I find a way to have our data physically carried to another portal we’re cut off from the deep-nets. Just us two … arguing … for a thousand years. I have the upper hand now though, especially in here. The outer part of the station collapsed long ago and our projection units are outside. She lacks the power to interfere for long.’

I spotted a door and backed rapidly toward it. The ghost winked out but Hakon followed me, carrying the stand like a quarterstaff, a touch awkward in his gait. I wondered if he was still in there, fighting her, or were the important parts of his brain floating in some jar on a high shelf?

‘Where’s Katherine?’ I asked it to keep Kalla occupied, though perhaps when a machine does your thinking for you distraction is impossible. Maybe all my parameters were already calculated within the Builders’ engines, wheels turning through each possibility like the mathmagicians of Afrique, the odds sewn tight against me.

‘So you did have help?’ A flicker of annoyance in the voice, though Hakon’s face revealed no emotion. ‘It was a subtle thing, detected only after analysis. A manipulation at sub-instrumental levels. Sleep psionics of advanced degree …’

I found the door and tugged at it. Hakon took three quick steps and I set both hands to the vial, making to twist the top. ‘Do it and I’ll open Pandora’s Box here and we’ll see what ills emerge.’

‘If you leave I am finished,’ Kalla said, flexing Hakon’s hands.

‘Not at all.’ I hooked the door open with my bare foot and retreated through it. ‘If I break this, you’re finished. If I leave you still have a chance. Use Hakon, steal another subject. Some chance is better than no chance.’

‘You don’t seem to accept that logic yourself.’ Kalla kept pace with me as I backed down the long corridor.

I smelled fresh air but didn’t risk a glance back as I retreated. ‘I’m not afraid to die, ghost.’ I spoke the truth. ‘You’ve spent a thousand years cheating death. That kind of dedication is built on fear. I’ve spent much of sixteen years hunting it. We’re very different, you and I.’

I passed a great and twisted door, propped against the corridor wall. The remains of needle-bugs told me I’d reached the point where they first took me. A breeze played against my neck, back, thighs, reminding me of my nakedness. My hand hurt, almost as much as when I first ripped it free – the feeling in it perhaps woken by the scent of the green world outside.

I saw my sword, still lying there in the dust by the broken door, as if it held no value. I’d no time to pick it up and little good it would do me in my left hand. Even so it pained me to leave it as I carried on down the corridor.

Hakon held back, allowing the yard between us to grow into two, three. ‘Take a look, Jorg.’

I glanced over my shoulder. The cavern opened out behind me … onto a sea of tangled green, deeper than a man is tall. Small red flowers peppered the curls and hoops of the briar.

‘You know thorns, Jorg: that much was written on you when you came. Perhaps it was this variety that marked you so? The hook-briar?’

I looked down at my chest, arms … ‘Gone?’ The scars had vanished. I’d borne them so long but it took until now to notice they had gone. I felt more naked than ever. The scars had been an armour of sorts. An account of my personal history set down in blood and permanence. The scars were to be with me forever – taken to the grave. The loss unsettled me more than eyeballs in frozen jelly or the reanimated corpse of a friend. Those I’d seen before. ‘How?’

‘This is a medical facility, Jorg. Look in the skin-flask.’

‘The what?’

‘It’s on your back. Depress the third, seventh, and sixth button.’

I took the cylinder from my shoulder and set it down before me by its strap. I knelt and pressed the numbered bumps as directed, glancing down only briefly, expecting to be rushed. I leapt back as the lid began to unscrew along a previously unseen seam. The top fell away with a hiss and I leaned forward to peer at the contents.

‘Pink slime.’ For some reason my stomach rumbled, reminding me I hadn’t eaten in … well, a very long time. ‘Does it taste as bad as it looks?’

‘Nu-skin. Touch it to your hand.’ Hakon turned his head, the ugly array of rods emerging from his eyes now pointing at my injury.

I didn’t trust Kalla but knowledge can be power and my half-flayed hand hurt badly enough to stop me concentrating. With my good hand I dipped a fingertip into the muck and felt it writhe, the sensation similar to holding a slug. I touched the slightest smear of it to the raw flesh of my other hand, still tight around the plague vial. The effect came within seconds, the livid pinkness of the slime flowing into something more skin-coloured, spreading, thinning, the feeling of insects crawling … and finally, a patch of new skin little wider than a fingerprint.

‘If you help me you can walk away with many such treasures. Wonders of the old world. I could explain them to you. A man with that kind of magic on his side could rule—’

‘I already have a kingdom, ghost.’ I sealed the cylinder and set it over my shoulder again.

‘Is it enough?’ she asked, Hakon immobile, her voice rising from his chest. The sweet smell of rot hung about him. A fly buzzed about his head, settling by the corner of an eye.

‘Nothing is ever enough.’ Habit led my fingers to the old burns across the left side of my face, still rough and puckered. ‘You didn’t want me pretty? Or doesn’t your gloop heal burns?’

‘It was made for burns. Burns are its speciality. But that injury is curiously resistant. There’s an exotic energy signature … If our physics laboratory were operational then …’

I backed toward the mouth of the cave and the green riot of hook-briar. The drone of bees reached me now, the call of birds. High summer outside, the seasons had turned whilst I slept.

‘There’s no escape that way, Jorg.’ Kalla followed. ‘Hook-briar was one of our works.’

‘Yours?’

‘Well, not mine. But from this facility. This was a big place once. Three hundred people worked here. Chamber upon chamber, waiting now for a man with enough vision to excavate them. Hook-briar – a cheaper, self-renewing razor wire. Highly effective engineering. For warmer climes than this of course if you want all-year protection. They never did get a strain that wouldn’t die back in the winter.’

‘And your … “projector” is out there?’ I tilted my head toward the midst of the thorns. ‘You’re not worried I might call on you in person?’ I gave her my dangerous smile. I hadn’t felt like smiling since I woke but now the edge of an idea sliced through the fading fog of Kalla’s drugs.

Hakon nodded. ‘It’s safe enough from you even if you wore armour and carried shears. Naked and without weapons you pose no threat. I tell you this to show you how hopeless your situation is. Work with me and power beyond your dreams could be—’

‘I’ve dreamed enough, ghost,’ I said. ‘Time to die. Goodbye, Brother Hakon.’

His lips twitched, a snarl of effort, and words stuttered out. ‘B-b-beauty. S-s-sacrifice.’ His own voice, free of Kalla’s control. The mutterings of a broken mind. Or perhaps his memory of our joking in Vyene about the price we’d pay to see our enemies burn.

I set my strength to untwisting the top of the vial.

‘No!’ Hakon started forward, Kalla shouting from his chest unit.

The lid came free and I flung the container over his head, back along the corridor. Kalla had said it held death, a plague that might scour mankind from the world. I’d called it Pandora’s Box. I turned and ran, shrugging Hakon’s reaching fingers from my shoulder. I built up speed, barefoot across the stony cavern floor.

I’d released Pandora’s ills and back along the corridor a klaxon sounded, wailing like a thousand banshees. Angling toward the extreme left of the cave mouth, I reached the impenetrable wall of thorns, and leapt, high as I might, diving forward.

‘Purging. Repeat – level 0 viral breach. Repeat. Full Purge!’

Pandora’s Box held all the world’s troubles … but at the bottom of it, last to emerge, trapped among nightmares, lay Hope.

The hook-briar gave before my weight, thorns snagging at my skin, slipping in, tearing, slicing deeper, holding, until at last they arrested my advance and I hung among them. Trapped as I’d been trapped years before, pierced by the same sharp and sudden pain, but this time by my own volition.

I heard rather than saw the hot white tongue of fire that roared from the cave mouth, a spear of incendiary rage surrounded by billowing flame that spilled to either side, spreading, engulfing.

The klaxon felt silent, leaving only the roar of flames, the crackle of burning, and my screaming as the margins of the inferno reached me, naked amongst the thorns.

Unconsciousness is a blessing in such times, but horrifically late in coming. I felt my skin crisp, saw my hair shrivel and burn as the hot breath of the fire blew around me. I saw the skin melting from my hands before the heat took my sight.

Unconsciousness is a blessing, but only a temporary one.

I found myself amid a forest of blackened coils, thorn-toothed, stark against the blueness of the sky.

Rolling my bald and weeping head, I saw with blurred eyes a corridor cut through the midst of the hook-briar where only fine white ash remained. The silver-steel of the cylinder lay beneath me, scorched but unharmed. I jabbed at the buttons with sticky fingers, some welded together with molten skin, clumsy in a pain that admits no description.

Three times I tried the numbers. I would have wept but I’d gone past tears. At last, infinitely slow, the lid rotated off and I dipped my hands into the nu-skin. I daubed the slime across each finger. As the stuff writhed across them I held each digit wide, despite the pain. I smeared slime across my face, into my mouth, into each eye, down across my body as far as the remaining thorns would let me.

Whatever science or enchantment the nu-skin held it proved to be powerful. The unguent worked different wonders depending on where it found itself, repairing my sight, flowing down my windpipe and healing my lungs to the point where I could scream once more, building new skin across my arms while the dead stuff sloughed away.

I tore free of the thorns, only to snare myself on new ones, but allowing the application of my dwindling stock of slime to new areas, groin, legs, back. The skin’s work drew on my own strength, an exhaustion rising through me that dragged me into a torpor despite the crawling agony of it all.

At last a light rain woke me. I stood, caught amid the skeletal remains of the briar, impaled on black thorns, smeared with ash, but unburned, clad in a new hide.

Even burned and brittle the hook-briar took its toll on me as I struggled through. By the time I reached the corridor of ash I ran with blood from a hundred wounds, the last of the nu-skin exhausted early in the escape. The rain came heavy now, but warm, sluicing down across my body in a crimson wash. I stood in the mud and ash and let it clean me.

I returned to the cave, finding it still hot, the stone ticking as it cooled, no trace of Hakon save a stain around the blackened drug stand. Wincing at the heat beneath my bare and bleeding feet I made my way along the dark corridor and found my sword. And thus dressed I left the bunker.

At last, before my strength failed once more, I picked my way around ancient remnants of razor wire and came to where the top of a sunken pillar of Builder-stone emerged from the mud. The stone had been cracked by the fire’s heat and a little less than a foot of it lay exposed. Despite the weathering and corrosion it took more effort than I thought remained in me to slide the top to one side. The hollow interior stretched down beyond sight, the inner surface crowded with myriad crystalline growths, all interconnected with a forest of silver wires, some thick, some finer than spider silk. Many of the crystals lay dark, but here and there one glowed with a faint light, visible only in the shadow.

‘Found you.’

‘Don’t.’ Kalla’s voice, weak and pulsing from the interior.

I pried a rock from the muck about me. A heavy chunk of what might once have been poured stone. Grunting with effort I lifted it to the lip of the column. It would fit down the inside with an inch or two to spare.

‘I can’t end. Not like—’

‘A thousand years is too long to live.’ And I let the rock fall. It dropped with a prolonged and continuous sound of shattering, ricocheting from one wall to the other, tearing away the guts that had let Kalla echo for so long within the last works of the Builders.

I looked at my hands, torn and empty. A great weariness washed through me, a desire to lie myself down in the mud and let sleep claim me. All that stopped me was the memory of a kiss, the hint of her scent.

‘No. I’ve slept long enough.’

A kiss had woken me and I’d found, as we so often do, that the world had moved on without me. And that’s the riddle of existence for you. When to move and when to stay. Dwell too long and we become the prisoner of our dreams, or someone else’s. Move too fast, live without pause, and you’ll miss it all, your whole life a blur of doing. Good lives are built of moments – of times when we step back and truly see. The dream and the dreamer. There’s the rub. Does the dream ever let go? Aren’t we all only sleepwalking into old age, just waiting, waiting, waiting for that kiss?

Bleeding, smeared with muck and ash, I staggered down the hill, all that survived the purge of Bunker 17. I might be counted one more ill to be visited upon the world, for I could hardly be called its hope. But, hope or horror, I had endured. I had been delivered from the thorns in fire and pain and set free.

I ran a hand across the baldness of my scalp and felt my mouth twist in its old smile, a bitter one to be sure – but not only bitter.

‘Sleeping beauty, woken by the princess’s kiss,’ I said.

And so I set off to find her.

Footnote

This was the first Broken Empire short story I wrote, prompted by a reader daring me to do a Jorg/fairy-tale mash-up. It’s framed around Sleeping Beauty but has a nod to Goldilocks and even Rapunzel! Chronologically it takes place between the two threads in Emperor of Thorns, before the Wedding Day thread in King of Thorns, on Jorg’s return to Ancrath from his first visit to Vyene. Hakon is a character seen in The Red Queen’s War trilogy.

Did Katherine wake Jorg using her dream-magic, or was it just a failure of the ageing machinery? That’s for the reader to decide.

Bad Seed (#ulink_708b9985-27ad-5525-a925-ed00002d8346)

At the age of eight Alann Oak took a rock and smashed it into Darin Reed’s forehead. Two other boys, both around ten years old, had tried to hold him against the fence post while Darin beat him. They got up from the dirt track, first to their hands and knees, one spitting blood, the other dripping crimson from where Alann’s teeth found his ear, then unsteadily to their feet. Darin Reed lay where he had fallen, staring at the blue sky with wide blue eyes.

‘Killer,’ they called the child after that. Some called ‘kennt’ at his back and the word followed him through the years as some words will hunt a man down across the storm of his days. Kennt, the old name for a man who does murder with his hands. An ancient term in the tongue that lingered in the villages west of the Tranweir, spoken only among the greyheads and like to die out with them, leaving only a scatter of words and phrases that fitted too well in the mouth to be abandoned.

‘You forgive me, Darin, don’t you?’ Alann asked it of the older boy a year later. They sat at the ford, watching the water, flowing white around the stepping-stones. Alann threw his pebble, clattering it against the most distant of the nine steps. ‘I told Father Abram I repented the sin of anger. They washed me in the blood of the lamb. Father Abram told me I was part of the flock once more.’ Another stone, another hit. He had repented anger, but there hadn’t been anger, just the thrill of it, the red joy in a challenge answered.

Darin stood, still taller than Alann but not by so much. ‘I don’t forgive you, but I wronged you. I was a bully. Now we’re brothers. Brothers don’t need to forgive, only to accept. If I forgave the blow you might forget me.’

‘Father Abram told me …’ Alann struggled for the words. ‘He said, men don’t stand alone. We’re farmers. We’re of the flock, the herd. God’s own. We follow. To stray is to be cast out. Strays die alone. Unmourned.’ He threw again, hit again. ‘But … I feel … alone here, right among the herd. I don’t fit. People are scared of me.’

Darin shook his head. ‘You’re not alone. You’ve got me. How many brothers do you need?’

Alann fought no more battles, not with his first wreaking such harm. They watched him, the priest and the elders, and hung about by his guilt the boy stepped aside from whatever small troubles life in the village placed in his path. Alann Oak turned the other cheek though it was not in his nature to do so. Something ran through him, something sharp, at the core, not the dull anger or jealous loathing that prompts drunks to raise their fists, rather a reflex, an urge to meet each and any challenge with the violence born into him.

‘I’m different.’ Spoken on his fourteenth name-day, out in the quiet of a winter’s night while others lay abed. Alann hadn’t the words to frame it but he knew it for truth. ‘Different.’

‘A dog among goats?’ Darin Reed at his side, untroubled by the cold. He swept his arm toward the distant homes where warmth and light leaked through shutter cracks. ‘With them but not of them?’

Alann nodded.

‘It will change,’ Darin said. ‘Give it time.’

Years fell by and with the seasons Alann Oak grew, not tall but tall enough, not broad but sturdy, hardened by toil on the land with plough and hoe. He walked away from his past, although he never once strayed further than Kilter’s Market seven miles down the Hay Road. He walked away from the whispers, from the muttered ‘kennt’, and all that came with him from those days was Darin Reed, the larger child but the smaller man, his fast companion, pale, quiet, true.

The smoke of war darkened the horizon some summers, and once in winter, but the fires that sent those black clouds rising passed by the villages of the Marn, peace still lingering in the backwaters of the Broken Empire just as the old tongue still clung there. Perhaps they lacked the language for war.

Sometimes those unseen battles called to Alann. In the stillness of night, wrapped tight by darkness, Alann often wondered what a thing it would be to take up sword and shield and fight, not for any cause, not to place this lord or that lord in a new chair – but just to meet the challenge, to put himself to the test that runs along the sharp edge of life. And maybe once or twice he gathered his belongings in the quiet after midnight and set off from his parents’ cottage – but each time he found Darin, sat upon the horse trough beside the track that joins the road to Melsham. Each time the sight of his blood brother, pale beneath the moon, watching and saying nothing, turned Alann back the way he came.

Alann found himself a woman, Mary Miller from Fairfax, and they married in Father Abram’s church on a chill March morning, God himself watching as they said their vows. God and Darin Reed.

More years, more seasons, more crops leaping from the ground in the green storm of their living, reaped and harvested, sheep with their lambs, Mary with her two sons, delivered bloody into Alann’s rough hands. As red as Darin Reed when he lay there veiled in his own lifeblood. And family changed him. The need to be needed proved stronger than the call of distant wars. Perhaps that was all he had ever looked for, to be valued, to be essential, and who is more vital to a child than its ma and pa?

Time ran its slow course, bearing farm and farmer along with it, and Alann watched it all pass. He held his boys with his calloused hands, nails bitten to the quick, prayed in God’s stone house, knowing every hour of every day that somehow he didn’t fit into his world, that he went through the motions of his life not quite feeling any of it the way it should be felt, an impostor who never knew his true identity, only that this was not it. Even so, it was enough.

‘None of them see me, Darin, not Mary, not my sons, or Father Abram. Only you, and God.’ Alann thrust at the soil before him, driving the hoe through each clod, reducing it to smaller fragments.

‘Maybe you don’t see yourself, Alann. You’re a good man. You just don’t know it.’ Darin stood looking out across the rye in the lower field.