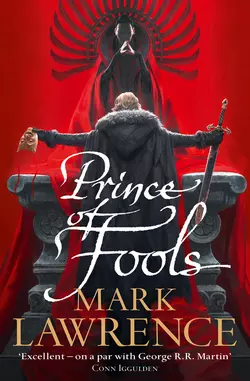

Prince of Fools

Mark Lawrence

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the critically acclaimed author of THE BROKEN EMPIRE series comes a brilliant new epic fantasy series, THE RED QUEEN’S WAR.I’m a liar and a cheat and a coward, but I will never, ever, let a friend down. Unless of course not letting them down requires honesty, fair play or bravery.The Red Queen is dreaded by the kings of the Broken Empire as they dread no other.Her grandson Jalan Kendeth – womaniser, gambler and all-out cad – is tenth in line to the throne. While his grandmother shapes the destiny of millions, Prince Jalan pursues his debauched pleasures.Until, that is, he gets entangled with Snorri ver Snagason, a huge Norse axeman and dragged against his will to the icy north…