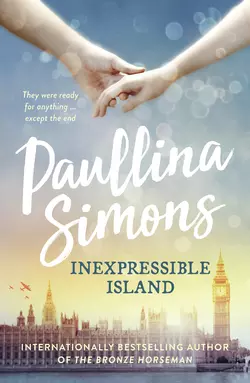

Inexpressible Island

Полина Саймонс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 864.66 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: They were ready for anything … except the end. The must-read conclusion to Paullina Simons′ epic End of Forever saga. Julian has lost everything he ever loved and is almost out of time. His life and death struggle against fate offers him one last chance to do the impossible and save the woman to whom he is permanently bound. Together, Julian and Josephine must wage war against the relentless dark force that threatens to destroy them. This fight will take everything they have and everything they are as they try once more to give each other their unfinished lives back. As time runs out for the star-crossed lovers, Julian learns that fate has one last cruel trick in store for them—and even a man who has lost everything still has something left to lose.