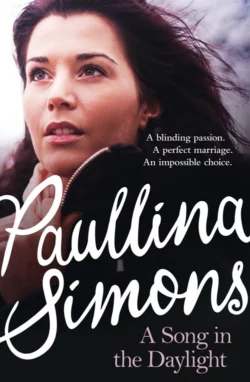

A Song in the Daylight

Полина Саймонс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1051.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the author of the top five bestseller ROAD TO PARADISE comes a novel of love, betrayal and redemption against the oddsHow well can you ever really know someone?If anyone asked Larissa′s husband, children or friends if she was happy, they would say yes. Sometimes too busy, sometimes irritable – but really, what in her wonderful life could be wrong? She has a happy marriage, a dream house, and everything she ever wanted at her fingertips.Yet a chance encounter with a young man new to town hits her like a lightning bolt. Their connection is electric. Suddenly her lovely home life seems claustrophobic, and the familiar mundane. Irresistible passion drives her to contemplate the unthinkable. But if she dares to make the impossible leap, what will her life be then? Whatever choice she makes, someone will be betrayed…