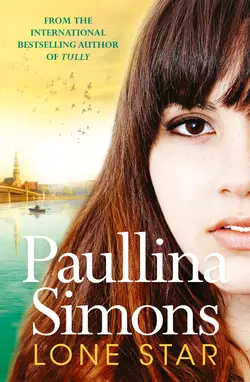

Lone Star

Полина Саймонс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 625.04 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Lone Star is another unforgettable love story from the best-selling author of Tully and The Bronze Horseman.Life isn’t about the destination, but the journey…Chloe is eager to drink in the sights and sounds of the Old World as she embarks on a European adventure with her closest friends. Buried in the treasures of the fledgling post-Communist world, Chloe finds a charming American vagabond named Johnny, who carries a guitar, an easy smile – and a lifetime of secrets.As she and her unlikely travelling companions traverse the continent, a train trip becomes a treacherous journey into Europe′s and Johnny′s darkest past – a journey that shatters Chloe′s future plans and puts in jeopardy everything she thought she wanted.From Treblinka to Trieste, from Carnikava to Krakow, the lovers and friends crack the facade that sustains their lifelong bonds to expose their truest, deepest desires and discover only one thing that′s certain: whether or not they reach their destination, their lives will never be the same.