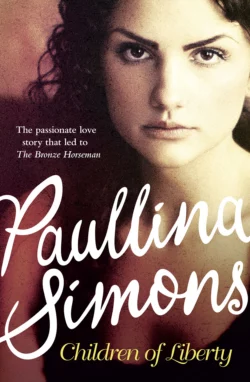

Children of Liberty

Полина Саймонс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.17 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From Paullina Simons who brought you the unforgettable The Bronze Horseman comes the much-anticipated Children of Liberty.“Never forget where you came from.”At the turn of the century and the dawning of the modern world, Gina sails from Sicily to Boston’s Freedom Docks to find a new and better life, and meets Harry Barrington, who is searching for his own place in the old world of New England.She is a penniless unrefined immigrant, he a first family Boston Blue-blood, yet they are hopelessly drawn to one another. Over their denials, their separations, and over time, Gina and Harry long to be together. Yet their union would leave a path of destruction in its wake that will swallow two families.