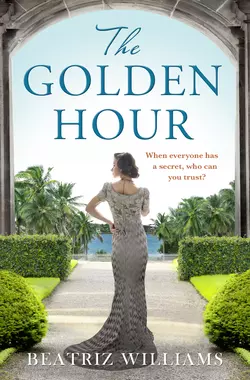

The Golden Hour

Beatriz Williams

From the New York Times bestselling author: a dazzling WWII epic spanning London, New York and the Bahamas and the most infamous couple of the age, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor The Bahamas, 1941. Newly-widowed Lulu Randolph arrives in Nassau to investigate the Governor and his wife for a New York society magazine whose readers have an insatiable appetite for news of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, that glamorous couple whose love affair nearly brought the British monarchy to its knees five years earlier. But beneath the glitter of Wallis and Edward’s marriage lies an ugly – and even treasonous – reality. In the middle of it all stands Benedict Thorpe: a handsome scientist of tremendous charm and murky national loyalties. When Nassau’s wealthiest man is murdered in one of the most notorious cases of the century, Lulu embarks on a journey to discover the truth behind the crime. The stories of two unforgettable women thread together in this extraordinary epic of sacrifice, human love and human courage, set against a shocking true crime… and the rise and fall of a legendary royal couple.

Beatriz Williams

Copyright (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in the UK by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Beatriz Williams

Cover design by Ellie Game @HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photographs © Lee Avison/Arcangel Images (woman and foreground), Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (trees, hedges and background)

Beatriz Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008380274

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780008380281

Version: 2019-08-06

Dedication (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

To women and men everywhere who live with depression.

You are loved. You are needed. The night will pass.

Contents

Cover (#ue6b990d6-4581-5312-85b5-048a873e801d)

Title Page (#u77846f30-c56c-502c-b3e4-b166a344cd8e)

Copyright

Dedication

In August 1940 … (#u6b66bb1b-0179-5877-9fcb-03d1020a7f2f)

PART I

Lulu: December 1943 (London)

Lulu: June 1941 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: July 1900 (Switzerland)

Lulu: July 1941 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: August 1900 (Switzerland)

Lulu: July 1941 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: September 1900 (Switzerland)

Lulu: July 1941 (The Bahamas)

PART II

Lulu: December 1943 (London)

Elfriede: October 1900 (Germany)

Lulu: December 1941 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: November 1900 (Germany)

Lulu: December 1941 (The Bahamas)

PART III

Lulu: December 1943 (London)

Elfriede: June 1905 (Florida)

Lulu: June 1942 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: July 1905 (Florida)

Lulu: June 1942 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: August 1905 (Berlin)

PART IV

Lulu: December 1943 (Scotland)

Lulu: July 1943 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: June 1916 (Scotland)

Lulu: July 1943 (The Bahamas)

Elfriede: August 1916 (Scotland)

Lulu: December 1943 (Scotland)

Lulu: July 1943 (The Bahamas)

Lulu: December 1943 (Scotland)

PART V

Lulu: November 1943 (The Bahamas)

PART VI

Ursula: January 1944 (Germany)

Lulu: March 1944 (Switzerland)

Elfriede: March 1944 (Switzerland)

Epilogue. Lulu: June 1951 (RMS Queen Mary, At Sea)

Historical Note

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Beatriz Williams

About the Publisher

In August 1940, the Duke of Windsor is appointed governor of the Bahamas by his brother, George VI, on the recommendation of Winston Churchill.

While the former king feels the appointment is beneath his station, he accepts, in the expectation that loyal service in this colonial outpost will lead to more prestigious assignments in the future.

But despite an exemplary public record of governorship for the duration of the Second World War, and the energetic support of the Duchess of Windsor as the governor’s wife, the duke is never again asked to serve his country in an official capacity.

PART I (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

LULU (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

DECEMBER 1943 (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

(London) (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

IN THE FOYER of the Basil Hotel in Cadogan Gardens, atop the tea-colored wallpaper, a sign advises guests that blackout hours will be observed strictly. Another sign reminds us that enemy ears are listening. The wallpaper’s crowded with tiny orange flowers that seem to have started out life as pink, and they put me in mind of a story I once read about a woman who stares at the wallpaper in her room until she goes batty. Although that wallpaper was yellow, as I recall, so I may have some time to go.

I consult my watch. Three twenty-two.

Outside the windows, the air’s darkening fast. Some combination of coal smoke and December fog and the early hour at which the sun goes down at this latitude, as if the wallpaper and the signboards and the piles of rubble across the street aren’t enough to make you melancholy. I check the watch again—three twenty-three, impossible—and my gaze happens to catch that of the desk clerk. He’s examining me over the top of a rickety pair of reading glasses, because he hasn’t liked the look of me from the beginning. Why should he? A woman shows up at your London hotel in the middle of December, the middle of wartime, tanned skin, American accent, unmistakable scent of the foreign about her. She pays for her room in advance and carries only a small suitcase. Now she’s awaiting some no-good rendezvous, right in the middle of your dank, shabby, respectable foyer, and you ought to telephone the authorities, just to be on the safe side. In fact, you probably have telephoned the authorities.

The clerk’s gaze flicks to the window, and then to the clock above the mantel behind me. He steps away from the reception desk and goes to pull down the blackout shades, to close the heavy chintz curtains. His limbs are frail and stiff; his suit was tailored in maybe the previous century. When he moves, his white hair flies away from his skull, and I catch a whiff of cologne that reminds me of a barbershop. I consider whether I should rise and help him. I consider whether he’d kill me for it.

Well. Not kill me exactly, not the literal act of murder. It seems the killing of people has got inside my head somehow. War will do that. War will turn killing into a commonplace act, a thing men do to each other every day, every instant, for no particular reason except not to be killed yourself, so that you start to expect it everywhere, murder hangs darkly over you and around you like an atmosphere. The valley of the shadow of death, that’s war. Killing for no particular reason. At least in regular life, when somebody kills somebody else, he generally has a damned good reason, at least so far as the killer’s concerned. It’s personal, it’s singular. As I observe the feathery movement of the clerk’s hair in the draft, I wonder how much reason a fellow like that needed to kill someone. We all have our breaking points, you know.

A bell jingles. The front door opens. A blast of chill air whooshes inside, along with a pale woman in a worn coat and a brown fedora, almost like a man’s. She brushes the damp from her sleeves and looks around, spies the clerk, who’s just crossing the foyer on his way back to the desk.

“I beg your pardon, my good man,” she begins, in a brisk, quiet English voice, and the light from the lamp catches her hair, caught up in a blond knot just beneath the brim of her hat. She’s not wearing cosmetics, except maybe a touch of lipstick, and you might say she doesn’t need any. There’s something Nordic about her, something that doesn’t need ornament. Height and blondness, all those things my own Italian mother couldn’t give me, though she gave me plenty else. There’s also something familiar about her. I’ve seen that mouth before, haven’t I? Those straight, thick eyebrows soaring above a pair of blue eyes.

But no. Surely not. Surely I’m only imagining this, surely I’m only seeing a resemblance because I want to see one. After all, it’s impossible, isn’t it? Margaret Thorpe won’t receive my letter until this evening, when she arrives home from whatever government building she inhabits during working hours. So this woman can’t be her, cannot possibly be my husband’s sister, however much the sight of those eyebrows sets my heart stuttering. Anyway, her head’s now turned toward the clerk, and from this angle she looks nothing like Thorpe, not at all. Unless—

The bell jingles again, dragging my attention back to the entryway. Another draft follows, and a man shambles past the door in a damp overcoat of navy blue, a hat glittering with mist. His face is pockmarked, the only notable thing about him. He casts a slow, bland expression around the room, and it seems to me that he takes in every detail, every flock on the wallpaper and spot on the upholstery, until he arrives, quite by accident, on me.

The woman’s still addressing the clerk. No notice of us at all. I climb to my feet. “Mr. B—?”

He steps forward and holds out his hand. “You must be Mrs. Thorpe,” he says warmly, and he takes my fingers between his two palms, as if we are father and daughter, meeting for tea after a short absence.

INSTEAD OF REMAINING INSIDE THE Basil Hotel foyer (in which the enemy ears might or might not be listening, but the desk clerk certainly is) we head out into the gloom. I tend to step briskly as a matter of habit, but Mr. B— (I’m afraid I can’t reveal his real name) shuffles along at an awkward gait, and it’s a chore to keep my limbs in check. I tuck my hands inside my pockets and drum my fingers against my thighs. I feel as if he should speak first. He’s the professional, after all.

“Well, Mrs. Thorpe,” he says at last. “I must congratulate you on your resolve. To have made your way to London in wartime, to have approached my office with such an extraordinary request—why, it’s the most astonishing thing I’ve seen in some time.”

“I hope you don’t mind.”

“Mind? Of course not. If there’s one thing we admire in this country, it’s dash. Dash and pluck, Mrs. Thorpe, which you appear to possess in abundance. How long had you two been married?”

“Since July.”

“This past July?”

“Yes. The seventh.”

“Ah. Just before he was captured, then. How dreadful.”

“It was months before I had any word at all. At first, I thought he’d been called out on another of his—whatever you call them—”

“Operations?”

“Yes, operations. But when he didn’t return …”

We pause to cross the street. I’ve allowed him to choose the route; I mean he’s the one who lives here, after all, the one who understands not just the map of London but the habits of the place. A couple of bicycles approach, one after the other, and while we wait for them to pass, Mr. B— speaks again.

“Mind you, it was quite against the rules.”

“What? What’s against the rules?”

Mr. B— stares not at my face, but along a line that passes right above my head, down the street to the approaching bicycles. “Marrying,” he says blandly.

The bicycles pass. We cross the street to enter a foggy square of red brick and white trim. Several of the houses are missing, simply not there, like teeth pulled from a jaw. Mr. B— leads me to the gardens in the middle, where we choose a wooden bench and sit about a foot apart, so that our arms and legs aren’t in any danger of touching, God forbid. The button at the wrist of my left-hand glove has come undone. I attempt to refasten it, but my fingers are too stiff.

“Of course, I quite understand your distress, Mrs. Thorpe,” he says, in the voice you might use to console a child. “It’s for that reason that we tend to discourage men such as Thorpe from forming any sort of personal attachment. To say nothing of marriage.”

“We’re all human, Mr. B—.”

“Still, it’s unwise. And then to allow you any hint of his purpose there in the Bahamas—”

“Oh, believe me, he never said a word about that. I was the one who put two and two together. I was on the inside, you see. A friend of the Windsors.”

“Were you really? Remarkable. Although I suppose …” He reaches into the pocket of his coat, brushing my arm with his elbow as he manipulates his fingers inside. He draws out a familiar white envelope. I recognize it because I carried this envelope myself, in a pocket next to my skin, for the entirety of the thirty-nine hours it took to cross the Atlantic, from Nassau to London, in a series of giant, rattling airplanes, before I stamped the upper right corner and posted it from a red metal postbox yesterday evening. And it’s funny, isn’t it, how a letter you mailed with your own two hands no longer belongs to you, once it begins that fateful drop through the slot. I glimpse my own handwriting, the stamp I placed there myself, and it’s like being reunited with an estranged child who has grown into adulthood.

“You suppose?”

Mr. B— taps the edge of the envelope against his knee. “I suppose it depends on what one means by friendship.”

“In wartime, friendship can mean anything, can’t it?”

“True enough. This note of yours. Quite astonished me this morning, when my secretary delivered it to my desk.”

“But you must have known Thorpe was captured.”

“Naturally. I take the most anxious interest in my agents, Mrs. Thorpe, and your—ah, your husband—he was one of—well. Well. That is to say, Mr. Thorpe in particular. We took the news very hard. Very hard indeed. Colditz, my God. Poor chap. Awful show.”

He takes out a cigarette case, opens the lid, and tilts it toward me. I select one, and he selects another. As he lights the match, he covers the flame with his cupped hand. We sit back against the bench and smoke quietly. The wind on my cheek is cold, and the air tastes of soot, and the sky’s blackening by the instant. At first I don’t quite understand what’s missing, until I realize it’s the absence of light. Not a pinprick escapes the windows around us, not a ray of comfort. It’s as if we’re the only two people alive in London.

“There used to be a railing,” says Mr. B—.

“What’s that?”

“Around the square gardens. A railing, to keep residents in and everybody else out, you see. They took it away and melted it down for iron.”

“I suppose it’s more democratic this way.”

“I suppose so. Here we are, after all, the two of us. Sitting on this bench, quite without permission.”

“And that’s what we’re fighting for, isn’t it? Democracy.”

He straightens his back against the bench. “Well, then. Leonora Thorpe. Plucky young American from across the ocean. What are we to do with you?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Why are you here? You’ll forgive me, but London isn’t the most peaceful of cities, at the moment. I imagine, wherever you come from—”

“Nassau.”

“Yes, Nassau. But you weren’t born there, were you?”

“No. I was raised in New York. I arrived in the Bahamas a couple of years ago, to cover the governor and his wife for a magazine.”

“A magazine?”

“Metropolitan magazine. Nothing serious, just society news. The American appetite for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor is just insatiable.”

Mr. B— sucks on his cigarette. “I must confess, it puzzles me. You Americans went to such trouble to rid yourselves of our quaint little monarchy.”

“Oh, we like to gossip about them, all right. Just not to let them rule over us and all that.”

“I imagine you were well paid?”

“Well enough.”

“A plum assignment, Mrs. Thorpe, spending the war in a tropical paradise. Plenty of food, plenty of money. Why didn’t you stay there?”

“Why? Isn’t it obvious?”

“But what’s to be gained by coming to London? Look around you. It’s the middle of the afternoon, and it’s already dark. Decent food in short supply. The weather—as you see—is simply dreadful, to say nothing of air raids and the threat of invasion. You ought to have stayed in the tropics, nice and safe, to wait for news.”

I crush out my cigarette on the arm of the bench.

“But that’s the thing, Mr. B—. I don’t mean to sit around and wait. That’s why I’ve come to London.”

I say this carelessly—come to London—as if it were as easy as that. As easy as boarding an ocean liner and waddling from meal to meal, deck chair to deck chair, until you step off a week later, and poof! you’re in England. And maybe it was that easy, in another time. These days, it’s not so simple. That ocean teems with objects that hope to kill you. And if you want to reach London in a hurry, well, the challenge grows by geometric leaps and bounds, because there’s only one way to cross the Atlantic in a hurry, and it doesn’t come cheap, believe me.

And then you contrive to meet this challenge. Clever you. You pay the necessary price, because you must, there’s no other choice. You find yourself strapped inside the comfortless fuselage of a B-24 Liberator as it prepares to separate you from the nice safe sun-soaked ground of the Bahamas and bear you, by leaps and bounds, to darkest England, a place you know only by hearsay. The engines gather power, the noise fills your ears like all the world’s bumblebees pollinating a single rose. The metal around you bickers and clatters, the world tilts, the air freezes, and there you are, eyes shut, stomach flipping, ears roaring, mouth watering, chest rattling, lungs panting, nerves screaming, heart aching, wishing you had goddamn well fallen in love with someone else. Someone you could live without.

But you can’t. So now you’re here in London. London at last, on a garden bench in the middle of a darkened city, next to the only man in the world who can help you. Except the fellow’s shaking his head, the fellow’s got no faith in you at all.

“Come to London,” he says. “How on earth did you manage it?”

“I managed it because I had to. I’d do anything to free my husband.”

“Free your husband? Is that the idea?”

“I damned well won’t run around Nassau going to parties while my husband rots away in the middle of Nazi Germany.”

Mr. B— extends his arm and flicks ash onto the gravel. His shoes are beautifully polished, his trousers creased. Standards must be kept. “Mrs. Thorpe,” he says, “I don’t know quite how to express this.”

“How about straight out? That’s how we Americans prefer it.”

“Then I’m afraid you’ve wasted your time. Once one of our men falls into enemy hands, why, he’s on his own. Thorpe knew this. We can’t possibly risk more agents on hairy schemes that—you’ll forgive me—offer almost no chance of success. We’re stretched enough as it is. We’re scarcely hanging on.”

“But I’m not asking you to risk anyone else. I’d go myself.”

“I’m afraid it’s impossible. Thorpe’s been trained. He knows it’s his duty to escape, not ours to spring him out, and I’ve no doubt he’s doing his utmost.”

“That’s not enough for me.”

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Thorpe,” Mr. B— says. “I don’t mean to be unkind. Naturally you’re suffering. It’s the most beastly news. One hopes for the best, of course. But one soldiers on. That’s all there is, just to soldier on.”

“That’s all terrific, if you’re a soldier. If you’re allowed to do something useful instead of twiddling your thumbs.”

“There are many ways in which women are able to serve the war effort, Mrs. Thorpe. And I can offer you my steadfast assurance that we’re doing our best, in my department and in Britain as a whole, all the services, every man Jack, to defeat Germany and bring your husband safely home.”

Across the street, a pair of women hurry down the sidewalk, buttoned up in wool coats and economical hats. The clatter of shoes echoes from the bricks, and it occurs to me how silent a city can be, when gas is rationed and private automobiles are banned. You can hear an omnibus rattle and grind from a couple of streets away, and you realize how alone you are, how desolate war is.

The women turn the corner. A man begins a slow, arthritic progress from the opposite direction, bent beneath the weight of his coat and hat. He’s smoking a cigarette. I figure the fellow’s probably deaf, but I speak softly anyway. Soft and firm.

“I understand your position, of course. I guess it’s about what I expected. I understand, I really do. But now I need you to understand me, Mr. B—.”

He turns his face toward me and lifts his eyebrows. At last, his voice goes a little cold, the way a man speaks to another man, his equal. “Oh? Understand what, Mrs. Thorpe? Let us be perfectly clear with each other.”

“All right, Mr. B—. Listen carefully. In the course of my service in Nassau, in my capacity as a journalist, as an intimate associate of the governor and his wife, I became privy to certain information. Do you catch my drift?”

There is this silence. I think, Well, he knows this already, doesn’t he? I wrote as much in my note. At the time, I thought I conveyed my meaning in circumspect sentences, that my note was a clever, sophisticated little epistle, but now it seems to me that my note was probably a masterpiece of amateurism, that Mr. B— probably laughed when he read it. Probably he’s suppressing his laughter right now. His silence is the silence of a man controlling his amusement.

He examines the end of his cigarette. “What kind of information?”

“You know. The kind of information that might prove embarrassing— embarrassing to say the least—were it to be made known to the general public.”

He drops his cigarette to the gravel and crushes it with his shoe. “Embarrassing to whom?”

“To the British government. To the king and queen.”

Mr. B— reaches into his jacket pocket and removes another cigarette from the case. He lights it with the same care as before, the same series of noises, the scratch and the flare, the covering of the flame. “Mrs. Thorpe,” he says softly, “I’m afraid I have a little confession to make.”

“Oh?”

“I may have stretched the truth just a bit, when I told you I was astonished by the contents of your letter.”

We still sit side by side, except we’ve turned a few degrees inward to address each other. Mr. B—’s elbow rests on the top slat of the bench. Because he’s looking at my face now, almost tenderly, I make a tremendous effort to keep my expression as still as possible. My fingers, however, have developed some kind of tremor. Imagine that.

“How so?” I ask.

“I received a memorandum a day or two ago. From a certain member of the Cabinet, in response to a cable sent him from Government House in Nassau. So we had some warning, you see, of your imminent arrival. We had some notion of what to expect.”

“I see.”

“Still, your note was—well, it was marvelous. I don’t wish to take anything away from that. My own men couldn’t have done better.”

“I’m flattered.”

He leans forward, so I can smell his cigarette breath, the faint echo of whatever it was he ate for lunch. “Mrs. Thorpe, I simply can’t allow that information to go any further. Do you understand?”

“Of course I understand. That’s why I’m offering to—”

He drops the cigarette in the gravel and crushes it with his heel. “No, my dear. I don’t think you really do understand.”

And I’m ashamed to say it’s only now I realize what an idiot I’ve been. Not until this instant does it occur to me to ask why, if Mr. B— received my note in the morning—my note hinting delicately of treason at the highest level, treason within the royal family itself—he waited until the fall of night to meet me, to draw me outside, to walk with me into a darkened square before a thousand windows closed for the blackout.

Why, indeed.

I rise from the bench. “Very well. If you’re not going to cooperate, I have no choice—”

With remarkable swiftness, he rises too, draws a small pistol from his pocket, and lodges the end of it in the middle of my coat, just above the knotted belt.

“Mrs. Thorpe. I’m afraid I must insist you give me whatever evidence you’ve obtained in this matter.”

“I don’t have it. Not right here.”

“Where, then?”

“In my hotel room.”

He considers. The pistol remains at my stomach, moving slightly at each beat of my heart. Though my gaze remains on his, I gather the details at the edge of my vision: the trees, bare of leaves; the shrubs, the plantings, all of them shadows against the night, against the murky buildings surrounding us. I observe the distant noise of another omnibus, a faint, drunken cheer from a pub nearby. Possibly, if I screamed, someone might hear me. But I would be dead by the time this noise reached a pair of human ears.

“It’s well hidden,” I continue. “I could save you a lot of trouble.”

Mr. B— nudges the pistol against my stomach. “Very well. Move slowly, please.”

As I begin my turn, I jerk my knee upward, bang smack into the center of his groin. A shot cracks out. I grab the pistol, burning my hand, and slam it into his head, right behind his left ear. He slumps to the ground, and let me tell you, I take off running, hoping to God I don’t have a bullet in me somewhere, hoping to God I knocked him out as well as down.

As I dart across the street, there’s a shout. I don’t stop to discover where it came from, or whom. The sidewalk’s empty, the street’s dark. The sky’s begun to drizzle. I pass a red postbox, the house with the grand piano in the window I noticed this morning, except you can’t see that piano right now, I can’t see anything, the whole world is dark and wet, each stoop concealing its own shadows. I cross another street, another, not stopping to check for traffic—there isn’t any, not with wartime restrictions on brave, threadbare London—until the familiar white signboard resolves out of the mist, BASIL HOTEL in quaint letters.

I pull back, undecided, but my momentum carries me forward into another human chest, female chest.

Oomph! she says, and snatches me by the arms. I lift my hands to push away. I spy a coat, a neck, a fringe of blond hair gathered into a bun.

The woman in the foyer.

“Miss Thorpe?” I gasp.

Her eyes are paler than her brother’s, but I recognize the shape, and the straight, thick eyebrows, though his are a darker gold. The same milky skin, the same freckles. She has pointed cheekbones, a wide, red mouth, a slim jaw. I’m able to drink in all these details because the world seems to have gone still, the clock seems to have stopped, and even the molecules of air, the motes of dust, have stuck in place. Only my blood moves, against the scorched skin of my right hand.

“You must be Leonora,” she says.

“Yes.”

She snatches my elbow and pulls me down the sidewalk. “Come along, quick. My flat’s just around the corner.”

And it occurs to me, as I career along in her wake, that this is just how her brother appeared in my life. Out of the blue in some foreign land, like a genie from a lamp, just when you needed a wish granted.

LULU (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

JUNE 1941 (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

(The Bahamas) (#u2f9b29cf-49c8-5644-8969-483b2ca3b6f4)

ON THE MAGAZINE COVER, the woman sits on a rattan sofa and the man sits on the floor at her feet, gazing not at the camera but upward, adoringly, at her. She smiles back in approval. She has a book in her lap, open to the frontispiece or maybe the table of contents—she doesn’t look as if she actually means to read it—and in her hair, a ribbon topped with a bow. (A bow, I tell you.) A pair of plump Union Jack sofa pillows flanks either side of her. A real domestic scene, a happy couple in a tasteful home. THE WINDSOR TEAM, reads the caption, in small, discreet letters at the bottom. At the top, much larger, white type inside a block of solid red: L I F E.

I’d been staring at this image, on and off, for most of the journey from New York, having paid a dime for the magazine itself at the newsstand in the Eastern Air Lines terminal building at LaGuardia Field. (It was the latest issue, now there’s coincidence for you.) I’d held it on my lap as what you might call a talisman, throughout each leg of the journey, each takeoff and landing, Richmond followed by Savannah followed by some swamp called Orlando followed by Miami at last, smacking down to earth at half past five in the afternoon, taxi to a shabby hotel, taxi back to the airfield this morning, and I still didn’t feel as if I’d quite gotten to the bottom of that photograph. Oh, sometimes I flipped the magazine open and read the article inside—the usual basket of eggs, served sunny-side up—but mostly I studied the picture on the cover. So carefully arranged, each detail in place. Those Union Jack pillows, for example. (We just couldn’t be any more patriotic, could we? Oh, my, no. We are as thoroughly British as afternoon tea.) That hair ribbon, the bow. (We are as charmingly, harmlessly feminine as the housewife next door.) The enormous jeweled brooch pinned to her striped jacket, just above the right breast— and what was it, anyway? The design, I mean. I squinted and peered and adjusted the angle of light, but I couldn’t make any sense of the shape. No matter. It was more brooch than I could afford, that was all, more jewels than I could ever bear on my own right breast. (We are not the housewife next door after all, are we? We are richer, better, royal. Even if we aren’t quite royal. Not according to the Royals. Still, more royal than you, Mrs. American Housewife.)

The airplane lurched. I peered through the window at the never-ending horizon, turquoise sea topped by a turquoise sky, and my stomach—never at home aboard moving objects—lurched too. According to my wristwatch, we were due at Nassau in twenty minutes, and the twenty-one seats of this modern all-metal Pan American airliner were crammed full of American tourists in Sunday best and businessmen in pressed suits, none of whose stomachs seemed troubled by the voyage. Just my dumb luck, my dumb stomach. Or was it my ears? Apparently motion sickness had something to do with your inner ear, the pressure of fluid inside versus the pressure of air without, and when the perception of movement on your insides didn’t agree with the perception of movement from your eyeballs, well, that’s where your stomach got into difficulty. I supposed that explanation made sense. All the world’s troubles seemed to come from friction of one kind or another. One thing rubbing up against another, and neither one backing down.

So I crossed my arms atop the magazine and gazed out into the distance—that was supposed to help—and chewed on the stick of Wrigley’s thoughtfully provided by the stewardess. By now, the vibration of the engines had taken up habitation inside my skull. This? This is nothing, sister, said the fellow sitting next to me on the Richmond– Savannah hop yesterday, local businessman type. You shoulda heard the racket on the old Ford tri-motor. Boy, that was some kind of noise, all right. Why, the girls sometimes had to use a megaphone, it was so loud. Now, this hunka junk, they put some insulation in her skin. You know what insulation is? Makes a whole lot of difference, believe you me. Here he rapped against the fuselage with his knuckles. Course, there ain’t no amount of insulation in the world can drown out the sound of a couple of Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp engines full throttle, no ma’am. That’s eight hundred horsepower apiece. Yep, she’s a classy bird, all right, the DC-three. You ever flown the sleeper model? Coast to coast in fifteen hours. That’s something, ain’t it? And so on. By the time we reached Savannah, I would gladly have taken the old Ford tri-motor and a pair of earplugs.

On the other hand, it could have been worse. When the talkative fellow from Richmond disembarked in Savannah, he was replaced by another fellow entirely, a meaty, sweating, silent specimen in a fine suit, reeking of booze and cigarettes, possessed of a sticky gaze. You know the type. By the time we were airborne, he had arranged himself luxuriously on the seat, insinuated his thigh against mine, and laid his hand several times on my knee, and as I slapped away his paw yet again, I would have given any amount of money to have Mr. Flapping Gums in his checked suit safely back by my side. And then. Then. The damned fellow turned up again this morning in an even more disreputable condition to board the daily Pan American flight to Nassau, fine suit now rumpled and stained, eyes now bloodshot and roving all over the place.

Thank God he hadn’t seemed to notice me. He sat in the second row, and by the stricken expression of the stewardess, hurrying back down the aisle this second with the Thermos of precious coffee, he hadn’t mended his ways during the night. I caught her eye and communicated sympathy into her, woman to woman, as best I could. She returned a small nod and continued down the aisle. The chewing gum was turning stale and hard. The wrapper had gone missing somewhere. I tore off a corner of page fourteen of Life magazine, folded the scrap, and slipped the wad discreetly inside.

In the seat next to mine, a gentleman looked up from his newspaper. He was tall and lean, almost thin, a loose skeleton of a fellow, and he’d made his way aboard with a small leather suitcase, climbing the stairs nimbly, the last in line. I hadn’t paid him much attention, except to note the interesting color of his hair, a gold fringe beneath the brim of his hat. He wore spectacles, and in contrast to my earlier companions, he’d hardly acknowledged me at all, except to duck his head and murmur a polite Good morning and an apology for intruding on my privacy. Though his legs were long, like a spider’s, he had folded them carefully to avoid touching mine, and when he’d opened his newspaper, he folded the sides back so they didn’t extend past the armrest between us. He’d refused the chewing gum, I remembered, though the tropical air bumped the airplane all over the sky. Other than that, he read his newspaper so quietly, turned and folded the pages with such a minimum of fuss, I confess I’d nearly forgotten he was there.

As the stewardess swept by, he bent the top of said newspaper in order to observe the fellow up front, unblinking, the way a bird-watcher might observe the course of nature from the security of his blind. I felt a stir of interest, I don’t know why. Maybe it was the quiet of him. Under cover of looking back for the stewardess, I contrived to glimpse his profile, which was younger than I thought, lightly freckled. All this, as I said, I captured in the course of a glance, but I have a good memory for faces.

After a minute or so, the gentleman folded his newspaper, murmured an apology, and rose from his seat. He set his newspaper on the seat and walked not to the front of the airplane, which he’d observed with such attention, but down the aisle to the rear, where the stewardess had gone. The airplane bumped along, the propellers droned. I looked back at the magazine on my lap—the windsor team, what did that mean, what exactly were they trying to convey, those two—and then out the window again. A series of pale golden islands passed beneath the wing, rendering the sea an even more alluring shade of turquoise, causing me almost to forget the slush in my stomach and the fuzz in my head, until the gentleman landed heavily back in the seat beside me.

Except it wasn’t the same gentleman. I knew that instantly. He was too massive, and he reeked of booze. A thigh came alongside mine, a paw settled on my knee.

“Kindly remove your hand,” I said, not kindly at all.

He leaned toward my ear and muttered something I won’t repeat.

I reached for the hand, but he was quicker and grabbed my fingers. I curled my other hand, my right hand, into a fist. I still don’t know what I meant to do with that fist, whether I really would have hit him with it. Probably I would have. The air inside our metal tube was hot, even at ten thousand feet, because of the white June sun and the warm June atmosphere and the windows that trapped it all inside, and the man’s hand was wet. I felt that bile in my throat, that heave, that grayness of vision that means you’re about to vomit, and I remember thinking I must avoid vomiting on the magazine at all costs, I couldn’t possibly upchuck my morning coffee on the pristine Windsor Team.

At that instant, the first gentleman returned. He laid a hand on the boozer’s shoulder and said, in a clear, soft English voice, “I believe you’ve made a mistake, sir.”

Without releasing my hand, the fellow turned and stretched his neck to take in the sight of the Englishman. “And I say it’s none of your business, sir.”

His voice, while slurred, wasn’t what you’d call rough. Vowels and consonants all in proper order, a conscious ironic emphasis on the word sir. He spoke like an educated man, thoroughly sauced but well brought up. You never could tell, could you?

“I’m terribly sorry. I’m afraid it is my business,” said the Englishman. “For one thing, you’re sitting on my newspaper.”

Again, he spoke softly. I don’t think the other passengers even knew what was going on, had even the slightest inkling—if they noticed at all—that these two weren’t exchanging a few friendly words about the weather or the Brooklyn Dodgers or Hitler’s moustache or something. The Englishman didn’t look my way at all. The boozer seemed to have forgotten me as well. His grip loosened. I yanked away my fingers and dug into my pocketbook for a handkerchief. The boozer reached slowly under his rump and drew out the crushed newspaper. The Miami Herald, read the masthead, sort of.

“There you are,” he said. “Now beat it.”

Those last words seemed out of place, coming from a voice like that, like he’d heard the phrase at the movies and had been waiting for the chance to sound like a real gangster. His empty hand rested on his knee and twitched, twitched. The fingers were clean, the square nails trimmed, the skin pink, except for an ugly, cracked, weeping sore on one of his knuckles.

The Englishman pushed back his glasses and leaned a fraction closer.

“I beg your pardon. I don’t believe I’ve made myself clear. I’d be very grateful if you’d return to your own seat, sir, and allow me to resume the use of mine.”

“You heard me,” said the boozer. “Scram.”

He spoke more loudly now, close to shouting, and his voice rang above the noise of the engine. People glanced our way, over their newspapers and magazines, and glanced back just as quickly. Nobody wanted trouble, not with a drunk. You couldn’t tell what a drunk might do, and here we flew, two miles above the ocean in a metal tube. I myself had begun to perspire. The sweat trickled from my armpits into the sleeves of my best blouse of pale blue crepe, my linen jacket. The boozer was getting angrier, despite the soothing, conciliatory nature of the Englishman’s voice, or maybe because of it. The force of his anger felt like a match in the act of striking, smelled like a striking match, the tang of saltpeter in your nose and the back of your throat. My fingers curled into the seams of my pocketbook.

“I’m afraid not,” said the Englishman.

The boozer looked like he was going to reply. He gathered himself, straightened his back, turned his head. His cheeks were mottled. The Englishman didn’t move, didn’t flinch. The boozer opened his mouth and caught his breath twice, a pair of small gasps. Then he closed his eyes and slumped forward, asleep. The Englishman removed his hand from the boozer’s shoulder and bent to sling the slack arm over his own shoulders.

“I’ll just escort this gentleman to his seat, shall I?” he said to me. “I’m awfully sorry for the trouble.”

No one spoke. No one moved. The stewardess stood in the aisle, braced on somebody’s headrest, hand cupped over mouth, while the Englishman hoisted the unconscious man to his feet and bore him— dragged him, really—toward the empty seat in the second row. The airplane found a downdraft and dropped, recovered, rattled about, dropped again. The Englishman lurched and caught himself on the back of the single seat to the left, third row. He apologized to the seat’s owner and staggered on. The stewardess then dashed forward and helped him lower the boozer into his seat like a sack of wet barley. Together they buckled him in, while the elderly woman to his right looked on distastefully. (I craned my neck to watch the show, believe me.)

Nobody knew what to say. Nobody knew quite what we had just witnessed. The engines screamed on, the airplane rattled like a can of nails. Across the aisle, a man in a suit of pale tropical wool turned back to his magazine. In the row ahead of me, the woman leaned to her husband and whispered something. I checked my watch. Only four minutes had passed, imagine that.

BY THE TIME THE ENGLISHMAN returned to his seat, the roar of the engines had deepened into a growl, and the airplane had begun to stagger downward into Nassau. A cloud wisped by the window and was gone. I feigned interest in the magazine, while my attention poured through the corner of my left eye in the direction of my neighbor, who picked his hat from the floor—it had fallen, apparently, during the scuffle or whatever it was—and placed it back in the bin. It turned out, his hair wasn’t thoroughly gold; there was a trace of red in the color, what they call a strawberry blond. I turned a page. He swung into place and reached for the newspaper, which I had retrieved and slid into the cloth pocket on the seat before him. It seemed like the least I could do, and besides, I can’t abide a messy floor.

“Thank you,” he said. “I do hope you weren’t troubled.”

“Not at all.”

He didn’t reply. I had a hundred questions to ask—foremost, was the boozer still alive—but I just turned the pages of the magazine in rapid succession until I ran out of paper altogether and closed the book on my lap, front cover facing up, THE WINDSOR TEAM locked in eternal amity with their Union Jack sofa pillows. The loudspeaker crackled and buzzed, something about landing shortly and the weather in Nassau being ninety-two degrees Fahrenheit, God save us.

I cleared my throat and asked the Englishman what brought him to Nassau, business or pleasure.

“I live here, in fact,” he said. “For the time being.”

“Oh! So you were visiting Florida?”

“Yes. My brother lives in a town called Cocoa, up the coast a bit. Lovely place by the ocean.” He nodded to the magazine. “Doing your research, are you?”

“Not exactly,” I said. “It was just a coincidence.”

“Ah.”

The airplane shook. I looked out the window and saw land, shrubby and verdant, and a long, pale beach meeting the surf, and a car flashing brilliantly along a road made of gray thread. “What a pair of romantics,” I heard myself say.

“Romantics? Do you really think so?”

I turned my head back and saw a serious profile, a pair of eyes squinted in thought behind the wire-rimmed spectacles. He hadn’t touched the newspaper. His lanky arms were folded across his chest, his right leg crossed over his left, immaculate, civilized. He didn’t look as if he’d lifted a pair of boots, let alone two hundred pounds of slack human weight.

“Don’t you? But it’s the love story of the century, hadn’t you heard?” I said. “The king who gave up his throne for the woman he loves.”

“A thoroughly modern thing to do. Not romantic at all.”

“How so?”

The airplane shuddered and thumped, bounced hard and settled. I looked out the window again and saw we had landed. The landscape outside teemed with color and vegetation and shimmering heat. I saw a cluster of palms, a low, rectangular building.

By the time we rolled to a stop, I had forgotten the question left dangling between us. The sound of his voice surprised me, but then everything about him had surprised me.

“A romantic would have sacrificed love for duty,” said the Englishman, “not the other way around.”

The airplane gave a final lurch and went still. He rose from his seat, removed his suitcase and his hat from the bin, removed my suitcase and gave it to me, and put his hat on his head. I said thank you. He told me to think nothing of it and wished me a good day, a pleasant stay in Nassau, and walked off the airplane. The sunshine flashed from the lenses of his spectacles.

As I passed the fellow from Savannah, he was still slumped in his seat, held in place by the safety belt, and I couldn’t honestly tell if he was dead or alive. The stewardess kept casting these anxious glances at his chest. I told her thank you for a memorable flight.

“Wasn’t it though,” she said. “Have a pleasant stay in Nassau.”

IN THE TERMINAL BUILDING, AS I waited my turn at the passport desk, I looked around for the blond man, but I didn’t see him. He might have gone anywhere. He might have come from anywhere. A fellow like that, he was like a djinn, like an enchanted creature from a fairy tale. Except this wasn’t a fairy tale, this was reality. He was made of common clay. He came from a woman and man, who fell in love, or had not. Who had married, or had not. Had spent a lifetime of nights together, or just one.

As I trudged out the terminal building to the street outside, I remember thinking a vast history lay behind this man, which I would never know.

ELFRIEDE (#ulink_863b5755-b920-50c2-8edc-9f74380fa0c4)

JULY 1900 (#ulink_863b5755-b920-50c2-8edc-9f74380fa0c4)

(Switzerland) (#ulink_863b5755-b920-50c2-8edc-9f74380fa0c4)

THE ENGLISHMAN ARRIVES at the clinic about an hour after lunchtime, while Elfriede sits in the main courtyard with Herr Doktor Hermann, discussing something she dreamed the night before. When she looks back on this moment, from a distance of years and—eventually— decades, she will remember nothing about the dream or the discussion, but she will hear the exact noise of the cartwheels and the iron hoofbeats on the paving stones of the drive as if the interior of her head were a phonograph disc, and these sounds imprinted it forever. She’ll remember the voices rising from the other side of the courtyard wall, and the smell of the pink, half-wild roses climbing that wall, and the way the sun burst free from the shade to warm the back of her neck and soak the courtyard in light.

Except that the sun doesn’t really come out at that moment. Memory, it turns out, is unreliable. All on its own, your memory gathers up helpful details that match your recollection of an event, whether or not those details actually existed at the time. But does it matter? For Elfriede, the sun comes out when the Englishman arrives. That’s how she remembers it. Sunshine, and the smell of roses.

ANYWAY, ONE OF THEM IS talking, Elfriede or Dr. Hermann, it doesn’t matter which one, and they both fall silent at the clatter of hoofbeats and cartwheels. “A new arrival?” Elfriede asks, after a moment.

“Yes, a lung patient,” answers the doctor. “Pneumonia.”

“How awful.”

“He’ll be kept in the infirmary wing, of course. There is no danger of transmission.”

“I meant, how awful for him.”

Dr. Hermann nods and makes a note in his little book. He makes notes continually during these sessions—conversations, he calls them, as if purely social—and Elfriede feels sometimes like a laboratory experiment, an unknown specimen of plant or animal, something abnormal. “How do you feel about this?” he asks, still writing, and for a moment Elfriede isn’t sure what he means, the note taking or the new patient. When she hesitates, he prompts her.

“I don’t mind at all,” she says. “I hope he recovers quickly. Why should I mind?”

“Indeed. Why should you mind?”

“I don’t know. But you seem to think I should.”

“What makes you say that?”

Another thing about Dr. Hermann, he never answers a question except with another question. He wants Elfriede to do all the talking, Elfriede to reveal herself. It’s the very latest treatment for nervous disorders such as hers, and really, as compared to some of the others, it’s not bad. Dr. Hermann is a large, soft-edged, round-shouldered man who folds his long limbs into normal-size chairs without the smallest irritation that they weren’t designed to accommodate him. There’s something malleable about him. Even his brown hair has a pliant quality. In later years, Elfriede will realize she never noticed the color of his eyes, nor can she recall his face. Just the soft, even shape of his voice, asking her questions.

She makes her answer as clear as possible, so he can’t find another question in it. “When I said How awful, you told me there was no danger of infection. So you must have thought I was afraid of that.”

Dr. Hermann adjusts his spectacles on the bridge of his nose. “Have you ever felt afraid of sickness, Elfriede?”

“No.” She stands up. “I’m going to take a walk now.”

ADMISSION TO THE CLINIC IS voluntary, and Elfriede is free to come and go as she likes, no restriction on movement, no requirement to stay. She could leave at any time, in fact.

Practically speaking, of course, that’s nearly impossible. The clinic sits on the top of a mountain, surrounded by wilderness and reached by a single, steep road in poor repair. Until the middle of the last century, it was a monastery of the Franciscan order, and the last of the monks sold the grounds and the ancient buildings to Dr. Hermann for next to nothing, on the condition that the crumbling walls remain a sanctuary for healing and peace. Patients seek out its geographic isolation and clean, healthful air for a variety of reasons—lung trouble, nervous disorders, broken hearts, discreet pregnancies, discreet abortions—but the general point is to separate oneself from civilization. You can’t leave without mountaineering skills or help from the outside, and Elfriede has neither. Also, she has no money—none she can produce from a pocket, anyway. So, when she rises from her bench and leaves the courtyard, walks along the covered passage to the old chapel, passes the chapel, and exits the building altogether to emerge on the fragrant, sunlit hillside, she doesn’t imagine she could hail the driver of the Englishman’s carriage and convince him to carry her back along the twenty miles of steep, rutted roadway, or that she could simply walk them on her own. Where would she go, anyway? Who would want her?

She just goes outside to be alone. That’s all she wants. To be left alone.

AS YOU MIGHT IMAGINE, THE quarters in this former Franciscan monastery are austere, to say the least. Elfriede’s bedroom is literally a monk’s cell, or rather two of them knocked together, and contains a single bed with a horsehair mattress, a stool, a plain wardrobe in which she hangs her three dresses, a dresser, and a desk and chair. There are no bookshelves. Elfriede’s free to borrow from the library, one volume at a time, but she wasn’t allowed to bring any books from home, nor is she allowed to receive any while she’s here. She’s encouraged to write, however. Each week, a fresh supply of notebooks arrives on her desk. Herr Doktor Hermann wants her to record her thoughts, her memories, and especially her dreams, and to bring these notebooks to their daily conversations so he can review the contents. When her notebooks aren’t sufficiently full, he doesn’t express any obvious displeasure to Elfriede. Of course, that would be unprofessional! Still she feels his displeasure like a disturbance in the air, turning his flared nostrils all pink, so she writes her devoirs daily, sometimes for hours, in order to satisfy his hunger for her subconscious mind. She also keeps another notebook under the horsehair mattress. This is the notebook that contains her real thoughts.

In the evenings, or during the day when the weather’s inclement, Elfriede has another way of finding solitude. She makes her way to the music room, which nobody ever enters except her, and plays on the piano from sheet music obtained from the library. Sometimes she’ll go on for hours, in chronological order of course, Bach to Haydn to Mozart to Beethoven to Schubert to Chopin, one must be methodical about such things. Then it’s midnight, and as the notes fade a silence fills the chamber like a thousand ears listening, an audience of spirits, and Elfriede can almost—but not quite—feel that her husband and son are among them.

TWO WEEKS LATER, ELFRIEDE ENCOUNTERS the Englishman for the first time. An orderly pushes him in a wheeled chair along one of the paved paths in the infirmary garden, and she observes them both from the hillside above. She’s just returned from a long, solitary hike, and the mountain air fills her lungs and her limbs, and the sunlight burns her face in a primitive way. She sits among the wildflowers and wraps her arms around her legs. Below her, about the size and importance of squirrels, the orderly and the Englishman come to a stop at the top of the rectangular path, inside a patch of sun. The orderly adjusts the blanket on the Englishman’s lap and they exchange a few words, although the breeze carries their voices away from Elfriede’s ears. After a last pat to the blanket, the orderly consults a pocket watch and heads back to the infirmary building, leaving the Englishman in the sunshine.

For some time, he sits without moving. The chair’s positioned at such an angle that she can’t see his face properly, and anyway Elfriede’s a bit nearsighted, so he might be asleep or he might just be too weak to move. Still, he must be past the crisis, or they wouldn’t have left him outside like this, would they?

Judging from the proportion of man to chair, he seems to be on the tall side, if slender. Of course, Elfriede’s husband is a giant, two meters tall and almost as broad, so most men look slender in comparison. Also, this fellow’s been sick, and he’s wearing those loose blue infirmary pajamas. His hair’s been shaved, and the remaining stubble is ginger, which catches a little sun and glints. Elfriede creeps closer. The brief, vibrant season of alpine wildflowers has arrived, and the meadow’s packed with their reds and oranges and violets, their sticky sage scent, clinging to Elfriede’s dress as she slides through the grass. She just wants to see his face, that’s all. Wants to know what an Englishman looks like. In her entire sheltered life, living in the country, small villages, Berlin once to shop for her trousseau, Frankfurt and Zurich glimpsed through the window of a train, she’s never met one.

Closer and closer she creeps, and still his face evades her. They’re pointed the same direction, toward the sun, and Elfriede sees only his profile, his closed left eye. He must be asleep, recovering from his illness. His color’s good, pale but not ghostly, no sign of fever, a few freckles sprinkled across the bridge of his nose. His left hand, lying upon the gray wool blanket, is long-fingered and elegant; the right hand remains out of view.

Elfriede stretches out her leg to slide a few centimeters closer, and without opening his eyes, the Englishman speaks, clear and just loud enough. “You might as well come on over here and introduce yourself.”

“Oh! I didn’t—”

“Yes, you did.” Now he opens his eyes and turns his head to face her, squinting a little and smiling a broad, electric smile that will come, in the fullness of time, to dominate her imagination, her consciousness and her unconsciousness, her blood and bones and hair and breath. “My God,” he says, in a more subdued voice, almost inaudible over the distance between them, “you’re beautiful, aren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“What are you doing here? You don’t look sick.” He glances cheerfully at her midsection. “Not up the duff, are you?”

He says those words—up the duff—in English, and Elfriede doesn’t understand them, so she just shakes her head. “A nervous disorder,” she calls back.

“You don’t look nervous.” He smiles at her confusion. “Never mind. I was only joking. I’m the family jester, I can’t help it. My name’s Thorpe. Wilfred Thorpe. I’d offer my hand, but I’m supposed to be keeping my germs to myself, at the present time.”

“Herr Thorpe. I’m Frau von Kleist.”

“Frau, is it? You look awfully young to be married.”

She hesitates. “I’m twenty-two.”

“As old as that?”

“And I have a little boy as well,” Elfriede adds, for no reason at all.

“Do you? Well, I won’t ask any awkward questions.” He turns his head back to the sun and closes his eyes. “Fine day, isn’t it? Won’t you come sit by me? I’ll promise not to cough on you.”

“I don’t know if it’s allowed.”

“Bugger that.” (In English again.) “I’ll take the blame, I promise. I’ll say I had a coughing fit, and you came to my aid in your selfless way.”

She laughs rustily and rises to her feet. In the course of her creeping, she’s come to within ten or twelve meters of the low stone wall that marks the perimeter of the garden, and it seems so silly and artificial to be holding a conversation in this manner, calling back and forth across the gulf, that Elfriede goes willingly to the brick wall and perches atop it, a meter or so from Herr Thorpe’s left shoulder, crossing her legs at the ankle.

“That’s better,” he says. “Easier on my lungs, anyway. You smell like wildflowers.”

“I’ve been sitting on them. You speak German very well.”

“So do you.”

She laughs again—so out of practice at laughing, but she can’t seem to help herself. “But it’s my native tongue, and you—you’re an Englishman, aren’t you?”

“Indeed I am. I learned my German in school, from a fearsome and very fluent master. Used to beat me with a cane whenever I slipped accidentally into the informal address.”

“That’s terrible.”

“It’s supposed to build character.” He opens his eyes and squints into the sun. He looks nothing like her husband, not just because he’s smaller and his head is shaved and his bones stick out from his skin, not just because he’s in a wheelchair while her husband is as huge and hale and hearty as a woodsman. Herr Thorpe is terribly plain, wide-faced and thick-lipped, freckled and ginger-haired, and the electricity of his smile can’t disguise his current state of febrile emaciation. She holds her breath in disbelief at the sharpness of his protruding bones, at the length of his pale eyelashes. He’s positively lanky inside his blue pajamas, and then there’s this enormous pumpkin head stuck on top of him.

“I’m glad you’re feeling better,” she says. “Pneumonia can be so dangerous.”

“Oh, I’m all right.”

“You wouldn’t have come here if you weren’t quite sick.”

“I couldn’t have come here at all if I’d been really sick. It’s a damned long journey from Vienna, you know. No, I came through the crisis all right, but the doctors were worried about my lungs, so they sent me here for recuperation. And my parents agreed because—well.”

“Because why?”

“A personal matter.”

“Some girl?” Elfriede asks boldly.

“Yes,” he says. “Some girl, I’m afraid. But it all seems rather long ago now. What about you?”

“A personal matter.”

“Let me guess. Coerced to marry some doddering old bastard against your will, and you’ve gone mad to escape him?”

“Nothing like that,” she says.

“Crossed in love?”

“No.”

“Some terrible grief, perhaps?”

“Nothing too terrible.”

The man drums his fingers on the armrest of his chair. “Have you been here long?”

“Long enough.”

“Ah. Then perhaps you can satisfy my curiosity on a small matter. You see, late in the evenings, when I’m meant to be sleeping, I sometimes hear the most extraordinary music floating into my chamber. Piano. Goes on for hours. I can’t decide whether it’s coming from outside the window or down the corridor. At first I thought I was dreaming. Do you hear it at all?”

“I—well, I …” She stops herself on the brink of a lie. “I’m afraid it’s me.”

“You? Ah. Ah.”

“I’m terribly sorry. I didn’t realize anyone could hear me. I’ll stop—”

“No! No. Don’t stop on my account.”

“If I’m keeping you awake—”

“I don’t mind at all, I assure you. It’s enchanting. Last night, the Chopin … I had the strangest feeling …”

“What?”

“Nothing. Enchanted, that’s all. Absolutely enchanted. And it was you, all along? All the more enchanting, then.”

From another man, this compliment might have sounded unctuous. But Mr. Thorpe speaks the word enchanting with such easy intimacy, Elfriede laughs instead, and laughter feels so good in her chest, in her head. She looks down at her feet, crossed at the ankles, and only then does she realize she’s blushing. She asks hastily, “What were you doing in Vienna?”

“What does anybody do in Vienna? Art, culture, philosophy. Opera and cafés and whatever amusement comes one’s way. I suppose I was attempting what they used to call a grand tour, except I kept getting stuck in places.” He pauses. “Delaying the inevitable.”

“What’s so inevitable?”

“Returning home. My father’s found a place for me in chambers.”

“What does this mean, ‘chambers’?”

“Law. I’m meant to become a lawyer.”

“How—how—”

“Grown up,” he says. “Grown up and rather dull. Pretty soon I shall get married, grow a beard, and start a brood of rascals of my own, and the whole cycle will start over again.” He looks as if he might say something else, but starts to cough instead. The sound is wet and wretched, cracking off the walls of the garden and the stone infirmary building across the grass.

“Are you all right?” Elfriede asks anxiously. “Shall I call the orderly?”

He waves the idea away. The fit dies down, and he leans his head back against the chair. “It’s not as bad as it sounds. It’s gotten much better, believe it or not.”

“You must have been at death’s door, then.”

“Yes, I rather think I was. It’s a real indignity, to catch pneumonia in the summertime. My mother says it was all the dissipation.”

“Dissipation? Really? You don’t seem like the dissipated sort.”

“Well, my mother’s idea of dissipation is a glass of sherry in the evening. Her side of the family is all Scotch Presbyterians. Strict,” he adds, apparently realizing Elfriede isn’t well acquainted with the tenets of Scotch Presbyterianism. “Damned strict.”

“So you were escaping.”

“Something like that. I finished university a year ago and thought—well, one’s only got this single chance to sin, before that inevitable time of life when one’s sins puncture the happiness of somebody else.”

“It’s not inevitable,” Elfriede says. “You don’t have to do it.”

“Do what? Go home and take up the law and become a respectable chap?”

“No. You should go back to Vienna instead. Go back to Vienna and the cafés and that girl of yours—”

“Frau von Kleist,” he says solemnly, “you’re making me weary with all your talk of rebellion. I’m a sick man, remember?”

“Of course.”

“I require a long period of rest and recuperation, not a program of debauchery.”

“How long—” She clears her throat and continues. “How long are you supposed to stay here?”

“As long as it takes. A month or two, perhaps. Just in time for autumn. And you, Frau von Kleist? How long do you expect to stay?”

She shrugs. “As long as it takes.”

“A month or two, perhaps? I’m afraid I don’t know much about nervous disorders.”

“More time than that, I think.”

There is a queer, heavy silence, the kind for which the clinic is famous. The deep peace of the mountains settles over Elfriede, a sense of motionless isolation that sometimes unnerves her, or increases her melancholy, because it seems as if she’s the only human being in the world, and she wants passionately to belong to somebody, anybody, almost anybody. Elfriede smells the wildflowers, the faint odor of something cooking in the refectory kitchen—it’s nearly lunchtime—and something else as well, a peculiar, indecipherable scent she will come to recognize as that of Herr Thorpe himself, a scent that will forever remind her of mountains, even in the middle of a teeming, dirty city.

Herr Thorpe murmurs, “There’s the orderly.”

Elfriede glances to the infirmary door, and the white-uniformed man presently emerging from it. A shimmer of panic crosses her chest, the way you feel when the nurse arrives to draw your blood from your veins. She climbs to her feet atop the wall.

“I must be going, Herr Thorpe—”

“Wilfred.”

“Wilfred.” She hesitates. “My name is Elfriede.”

He presents her with that wide grin, one eye squinted. “Why, it’s practically the same as mine! What are the chances, do you think?”

“Very slim, I think.”

Wilfred puts his hand to his heart. “Shattered. Will I see you again?”

She leaps back to the meadow side, which is about a half meter higher than the garden, rising upward along a soft, rounded hill. “I don’t see why we should. We occupy entirely different wings of the clinic.”

“And yet you’re here.”

“A mistake!” she says, over her shoulder, as she starts to climb the hill.

Wilfred’s voice carries after her. “There are no mistakes, Elfriede the Fair! Only fate!”

Elfriede climbs quickly, and the word fate is so thin and distant, it’s almost out of earshot. Nevertheless, she hears it. In fact, it echoes inside her head, over and over, in time to the heavy smack of her heart as she approaches the summit of the hill. She tells herself it’s only the effort of the climb, the thin air, the anticipation of the view from the top.

LULU (#ulink_02831f02-135a-5bc6-b2fd-adcfc6a9b336)

JULY 1941 (#ulink_02831f02-135a-5bc6-b2fd-adcfc6a9b336)

(The Bahamas) (#ulink_02831f02-135a-5bc6-b2fd-adcfc6a9b336)

EVERY TOWN HAS its watering hole, where everybody gathers to share a few drinks and some human news, and in Nassau that particular place was the bar of the Prince George Hotel. You couldn’t miss it. If, newly disgorged from some steamship onto the hot, smoky docks of Nassau Harbor, you staggered with your suitcase across Bay Street to shelter from the sun, you found yourself bang under the awning of the Prince George. And since the Prince George, as a matter of tradition, offered the arriving tourist his first glass of rum punch gratis, why, you can see how the bar developed a loyal following. I should know, believe me, even though I’d arrived by air instead of by sea. That punch went down so well, I made straight for the reception desk and booked a room. Three weeks later, I had almost forgotten I’d lived anywhere else. Every evening at six sharp, I made my way downstairs and took up a stool three seats down from the left, and the bartender—we’ll call him Jack—whipped up a cocktail while I lit a cigarette from a case full of Parliaments, a brand relatively rare in New York City but nigh ubiquitous in this British Crown colony. So began my twentieth night in Nassau. Now pay attention.

Jack was the kind of bartender who sized you up first and decided for himself what kind of drink you needed. On this particular evening, with the place just loosely occupied and the afternoon sun still filling the windows, he took a bit of time and asked, “Be a double for you, Mrs. Randolph? Look like you been dropping bombs all over Germany today.”

“Nothing as exciting as that.” I rested my left hand on the thick, sleek varnish and stared at the gold band on my fourth finger. “Just a day with the ladies at the Red Cross.”

Jack made a low, slow whistle. “Since when?”

“Since this morning, when the nice fellow in charge of the magazine was so dear as to send me one of his telegrams to go with my breakfast.”

“The good kind of telegram?”

“See for yourself.” I set the cigarette in the ashtray, pulled the yellow envelope from my pocketbook, and removed the wisp of paper, which I spread out flat on the counter before me. How I hated the color yellow.

HAPPY ANNIVERSARY STOP TODAY NOW THREE WEEKS SINCE YOUR DEPARTURE NASSAU STOP TOTAL EXPENSES TO MAGAZINE $803.22 STOP TOTAL EXCLUSIVE WINDSOR SCOOPS ZERO STOP RETURN TO NEW YORK IMMEDIATELY REPEAT IMMEDIATELY STOP NOT ONE MORE PENNY EXPENSES WILL BE PAID BY THIS MAGAZINE=

=S. B. LIGHTFOOT

Jack peered over and whistled. Above our heads, a ceiling fan purred and purred, lifting the ends of my hair. Jack shook his head and returned to his bottles.

“So you see,” I continued, replacing telegram in envelope and envelope in pocketbook, “my time in Nassau may be winding to an end.”

“Don’t you like it here, Mrs. Randolph?”

“Very much. But I can’t stick around if the magazine’s cutting off my expenses.”

“You could write them a story, like this fellow suggests.”

I inclined my head to the pocketbook. “This fellow? You mean Lightfoot? That’s a nice way of putting it. Orders, is more like it.”

“So? Write the fellow a story.”

“It ain’t that easy, sonny,” I said. “There’s only one thing to write about in this town, this blazing, backward, godforsaken burg, and it turns out you can’t just waltz right into Government House and ask to see the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, s’il vous plaît, and make it snappy.”

“I guess not, at that.”

“No, sir. You’ve got to weave your way into society, it seems. For starters, you have to join the local Red Cross, of which said duchess is president, and make nice with the ladies.”

“That bad, was it?”

“It was awful.”

Jack set the drink in front of me. A martini, it turned out. “Compliments of an admirer.”

“A what?” I sputtered into the glass.

“An admirer, like I said. And that’s all I’m saying.” Jack zipped his lips.

I set down the glass and lifted the cigarette. Jack observed me with interest, thick eyebrows cocked. When I’d taken the first long drag, and another sip from the martini, I crossed my legs and began a survey of the room around me. As you might expect, there was plenty of room to survey, plenty of height and arch, plenty of solid rectangular pillars done in handsome raised wood paneling, plenty of large, masculine chairs and ashtrays on little tables. Not so many customers. Everybody still out enjoying the sunshine, no doubt, and aside from the elderly gent near the window, buried in his newspaper, and the two fellows in linen suits having an earnest discussion in an alcove, the joint was empty. I turned back to Jack.

“Not the old man with the newspaper, I hope?”

“He’s mighty rich, Mrs. Randolph. Beggars can’t be choosers.”

“Are you calling me a beggar, Jack?”

Jack’s face assumed an aspect of innocence. Above his head, the glasses glittered in their rows, highballs and lowballs, champagne coupes and brandy snifters, not a speck of dust, not a hair’s width out of order. “Just an old saying, Mrs. Randolph,” he said. “Something my mama used to tell me, that’s all.”

“I have my faults, I’m the first to admit. But I’ve never begged for a dime in my life, and I don’t intend to start now.” I tilted my head toward the window. “Certainly not with some old moneybags trying his luck in a hotel lounge.”

“You have your standards, is that what you’re getting at?”

“I have my standards.”

“Oh, then I should take back this little glass here?”

I slapped away his hand. “Don’t you dare. The poor fellow’s perfectly free to buy me all the drinks he wants. So long as he understands he’s not getting his money’s worth.”

“Aw, he’s not so bad. Just look at the poor sucker. Got most of his hair. Nice clean suit. Shoes all shiny. Can’t see his teeth, but I bet he’s got a few left.”

“I’ll take your word for that.”

“You’re a real tough dame, you know that? A lot of pretty girls might take pity on a nice guy like that, money to burn. A one-way ticket to Easy Street.”

“I’m not a lot of girls, am I? Besides,” I said, reaching for the ashtray, “I happen to know firsthand where that kind of arrangement ends up, and it’s not Easy Street, believe me.”

The ashtray, if you’re asking, was a heavy old thing made of silver and embossed in the middle with what seemed to be a tavern scene. A border wound around the edges in a series of scrolls, dipping now and then to make space for a resting cigarette. I knocked a crumb of ash inside and measured the weight of Jack’s curiosity on the top of my head. Not that I blamed him. You said a provocative thing like that, you expected someone to wonder what you meant by it, to clear his throat and ask you for a detail or two.

Jack’s black waistcoat shifted in the background, his crisp white sleeves. He put away the bottle of gin on the shelf behind him and said, over his shoulder, “Just as well, I guess, he ain’t the fellow who bought your martini.”

“But you said—”

“You said.” Jack turned back to me and grinned. “I was just following along, you see?”

“I can’t tell you how delighted I am to have amused you.”

“Now, don’t be sore with me, Mrs. Randolph. I’m sworn to secrecy, that’s all.”

“You’re teasing me, aren’t you? I’ll bet this admirer of yours doesn’t even exist. You just poured me a free drink for your own entertainment.”

“Oh, he exists, all right. Paid me up front and everything. Nice tip.”

“Is he here right now?”

“In this room?” Jack’s gaze slid to the door, traveled along the walls, the panel and polish, the glittering windows, and returned to me. “’Fraid I can’t say. Kind of a shy fella, your beau. But don’t you fret. I got the feeling he’ll make himself known to you, when he’s good and ready.”

Before me, the martini formed a tranquil circle in its glass, a cool pool. Not a single flaw disturbed its surface. I pondered the chemical properties of liquids, the infinitesimal bonds of electricity that secured them together in such perfect order, the beautiful molecules held flat in my glass by gravity. The great mystery eluded me, as ever.

“How long have you tended bar, Jack?” I asked.

“How long have I tended bar? Or tended this bar here?”

“Tended bar at all, I guess.”

“Well, now.” He shut one eye and judged the ceiling. “Landed here in Nassau in twenty-one when I was just a wee lad, helping my dad with the old schooner—Lord, what a sweet ship she was—”

“Rum-running, you mean.”

“Just engaging in a little maritime commerce, Mrs. Randolph, serving the needs of you poor suckers dying of thirst back home. Used to load and unload them crates of liquor all the livelong day. Oh, but we lived like kings in Nassau back then. Those were good years.” He shook his head and wiped some invisible smudge of something-or-other from the counter. “Then they brought back the liquor trade stateside.”

“Hallelujah.”

“For you folks back home, maybe. Come to find out, my dad spent all the money from those years, every damn penny, Mrs. Randolph. Left me here in Nassau, broke as a stick. Lucky I knew a fellow who tended bar in those days. Took me under his wing, taught me the trade. Now here I am.” Jack spread his arms. “Got my domain. Nothing happens here without my say-so, Mrs. Randolph, and don’t you forget that. You got a problem with any fellow here, you come to me.”

He was a large man, Jack, maybe more wide than tall, but still. I found myself wanting to wrap my arms around that comfortable girth and kiss his rib cage. At the thought of this act, the image it evoked in my imagination, I directed a tiny smile at the remnants of my drink and asked, “Why do you like me so much, Jack?”

“Because you’re an honest dame, Mrs. Randolph. Honest and kindhearted.”

“This fellow of yours. Is he good enough for me?”

“Nobody’s good enough for you, Mrs. Randolph, not in my book.” He leaned forward an inch or two. “Between you and me, there’s been a lot of fellows asking. Pretty lady, drinking alone, kind of sad and don’t-touch-me. But this fellow is the first fellow I said could buy you a drink.”

“A fine endorsement.”

“Now it’s up to you, Mrs. Randolph. You’re a real good judge, I’ll bet. You just watch yourself around here, that’s all.”

“I thought you said he met your approval.”

“Oh, I wasn’t talking about him.” Jack pulled back and set the glass back on its shelf. “Talking about everything else, everything and everyone else on this island, but especially that duchess and her husband, them two sleek blue jays in a nest, looking out for nobody but themselves. You watch yourself.”

“Watch myself? What for? When I can’t seem to buy myself even a peep inside that nest. I spent all morning at their damned headquarters, the Red Cross, stuffing packages and sitting through the dullest committee meeting in the world, going out of my mind, just to wrangle myself an invitation to the party at Government House on Saturday, and then the duchess finally turns up, and do you know what she says?”

Jack makes a slice along his throat. “Off with your head?”

“Worse. Enchanted to meet you, Mrs. Randolph.”

“That’s all? Sounds all right to me.”

“You don’t know how it is with these people. She locks eyes with you, see, like you’re the only person in the room, the only person in the world, pixie dust glitters in the air around you, and she takes your hand and says, Enchanted to meet you, and you think to yourself, She likes me! She’s enchanted, she said it herself! We’re going to be the best of friends! Then she drops your hand and turns to the next woman and locks eyes with her, and you feel like a sucker. No, you are a sucker. Sucked in by the oldest trick in the book.” There was a stir to my right, somebody approaching the bar. I glanced out the side of my eye and recognized, or thought I recognized, a certain man sliding into position a few stools down, tall, polished, Spanish or French or something, air of importance. Jack, on the other hand, made not the slightest sign of having noticed him. I leaned my elbow on the counter and said, “Maybe I ought to just read the stars and give up.”