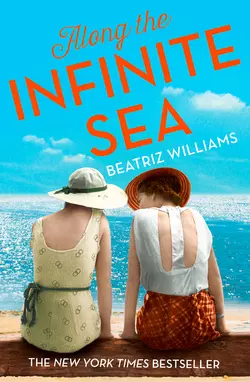

Along the Infinite Sea: Love, friendship and heartbreak, the perfect summer read

Beatriz Williams

Decadent and evocative storytelling at its very best., by NEW YORK TIMES bestseller, Beatriz Williams1966, FloridaPepper Schuyler is the kind of woman society loves and loves to talk about – a dazzling being who men watch across crowded, smoky rooms, and women keep their husbands away from. Yet the legend of Pepper is far from the truth…1935, Côte d’AzurNineteen-year-old ingénue Annabelle de Créouville leaves her father’s crumbling chateau to help a handsome German Jew fleeing from the Nazi regime – and from the other man with whom Annabelle’s future is inextricably entangled. Falling headlong in love as is only possible for the first time, Annabelle follows her heart from Antibes, to Paris, to pre-war Berlin, torn between two very different men, and two very different endings…

Copyright (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by Penguin Group USA 2015

First published in the UK by Harper 2015

Copyright © Beatriz Williams

Cover layout design © HarperCollinPublishers Ltd 2015Cover photograph courtesy of the F.C. Gundlach Foundation (Two Women on the Beach, 1936. By Yva / Else Neuländer).

All other photographs by Cherie Chapman, (sea and sky). Cover texture © CGTextures (wood).

Beatriz Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008134952

Ebook Edition © November 2015 ISBN: 9780008134969

Version 2015-09-09

Dedication (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

To those who escaped in time

and those who did not

and those who risked their lives to help

Table of Contents

Cover (#u08326c7f-7246-52cd-82a4-74e19b768658)

Title Page (#u7b94dc70-2e07-5ab5-80f5-e0e8e1011343)

Copyright (#u4a678369-3612-5fe1-9da9-442fd9319c7c)

Dedication (#u41392eb4-30bf-5621-aaf1-9c3ea60ddb5f)

Overture (#uce2b5aad-44c6-5976-89a5-de65e8dd1367)

Annabelle (#u413915d3-6aa7-52cc-9b72-bfc21927173e)

First Movement (#u3ad21e12-3fbd-5ea0-982e-2a998a6234a4)

Pepper (#u61a423d5-8390-58e6-acac-352b693eedbe)

Annabelle (#u25ccca75-d58b-52c4-a4e1-aaf0b0e71f1e)

Pepper (#u05679e43-912f-5676-936c-fcebc080d329)

Annabelle (#ube1aa5e4-e489-5793-88d0-09764c342067)

Pepper (#ue2ce6c46-dcca-5077-8b9b-e758fa90318e)

Annabelle (#u6bcf528b-bdf8-59f2-830c-63e60a11238f)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Second Movement (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Intermezzo (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Third Movement (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourth Movement (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifth Movement (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper (#litres_trial_promo)

Annabelle (#litres_trial_promo)

Coda (#litres_trial_promo)

Stefan (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Note on the Cover, From the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Overture (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

“To see all without looking;

to hear all without listening.”

CÉSAR RITZ

King of Hoteliers, Hotelier of Kings

ANNABELLE (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

Paris • 1937

All you really need to know about the Paris Ritz is this: by the middle of 1937, Coco Chanel was living in a handsome suite on the third floor, and the bartender—an intuitive mixologist named Frank Meier—had invented the Bloody Mary sixteen summers earlier to cure a Hemingway hangover.

Mind you, when I arrived at Nick Greenwald’s farewell party on that hot July night, I wasn’t altogether aware of this history. I didn’t run with the Ritz crowd. Mosquitoes, my husband called them. And maybe I should have listened to my husband. Maybe no good could come from visiting the bar at the Paris Ritz; maybe you were doomed to commit some frivolous and irresponsible act, maybe you were doomed to hover around dangerously until you had drawn the blood from another human being or else had your own blood drawn instead.

But Johann—my husband—wasn’t around that night. I tiptoed in through the unfashionable Place Vendôme entrance on my brother’s arm instead, since Johann had been recalled to Berlin for an assignment of a few months that had stretched into several. In those days, you couldn’t just flit back and forth between Paris and Berlin, any more than you could flit between heaven and hell; and furthermore, why would you want to? Paris had everything I needed, everything I loved, and Berlin in 1937 was no place for a liberal-minded woman nurturing a young child and an impossible rift in her marriage. I stayed defiantly in France, where you could still attend a party for a man named Greenwald, where anyone could dine where he pleased and shop and bank where he pleased, where you could sleep with anyone who suited you, and it wasn’t a crime.

For the sake of everyone’s good time, I suppose it was just as well that my husband remained in Berlin, since Nick Greenwald and Johann von Kleist weren’t what you’d call bosom friends, for all the obvious reasons. But Nick and I were a different story. Nick and I understood each other: first, because we were both Americans living in Paris, and second, because we shared a little secret together, the kind of secret you could never, ever share with anyone else. Of all my brother’s friends, Nick was the only one who didn’t resent me for marrying a general in the German army. Good old Nick. He knew I’d had my reasons.

The salon was hot, and Nick was in his shirtsleeves, though he still retained his waistcoat and a neat white bow tie, the kind you needed a valet to arrange properly. He turned at the sound of my voice. “Annabelle! Here at last.”

“Not so very late, am I?” I said.

We kissed, and he and Charles shook hands. Not that Charles paid the transaction much attention; he was transfixed by the black-haired beauty who lounged at Nick’s side in a shimmering silver-blue dress that matched her eyes. A long cigarette dangled from her fingers. Nick turned to her and placed his hand at the small of her back. “Annabelle, Charlie. I don’t think you’ve met Budgie Byrne. An old college friend.”

We said enchantée. Miss Byrne took little notice. Her handshake was slender and lacked conviction. She slipped her arm through Nick’s and whispered in his ear, and they shimmered off together to the bar inside a haze of expensive perfume. The back of Miss Byrne’s dress swooped down almost to the point of no return, and her naked skin was like a spill of milk, kept from running over the edge by Nick’s large palm.

Charles covered his cheek with his right hand—the same hand that Miss Byrne had just touched with her limp and slender fingers—and said that bastard always got the best-looking women.

I watched Nick’s back disappear into the crowd, and I was about to tell Charles that he didn’t need to worry, that Nick didn’t really look all that happy with his companion and Charles might want to give the delectably disinterested Miss Byrne another try in an hour, but at that exact instant a voice came over my shoulder, the last voice I expected to hear at the Paris Ritz on this night in the smoldering middle of July.

“My God,” it said, a little slurry. “If it isn’t the baroness herself.”

I thought perhaps I was hallucinating, or mistaken. It wouldn’t be the first time. For the past two years, I’d heard this voice everywhere: department stores and elevators and street corners. I’d seen its owner in every possible nook, in every conceivable disguise, only to discover that the supposed encounter was only a false alarm, a collision of deluded molecules inside my own head, and the proximate cause of the leap in my blood proved to be an ordinary citizen after all. Just an everyday fellow who happened to have dark hair or a deep voice or a certain shape to the back of his neck. In the instant of revelation, I never knew whether to be relieved or disappointed. Whether to lament or hallelujah. Either way, the experience wasn’t a pleasant one, at least not in the way we ordinarily experience pleasure, as a benevolent thing that massages the nerves into a sensation of well-being.

Either way, I had committed a kind of adultery of the heart, hadn’t I, and since I couldn’t bear the thought of adultery in any form, I learned to ignore the false alarm when it rang and rang and rang. Like the good wife I was, I learned to maintain my poise during these moments of intense delusion.

So there. Instead of bolting at the slurry word baroness, I took my deluded molecules in hand and said: Surely not.

Instead of spinning like a top, I turned like a figurine on a music box, in such a way that you could almost hear the tinkling Tchaikovsky in my gears.

A man came into view, quite lifelike, quite familiar, tall and just so in his formal blacks and white points, dark hair curling into his forehead the way your lover’s hair does in your wilder dreams. He was holding a lowball glass and a brown Turkish cigarette in his right hand, and he took in everything at a glance: my jewels, my extravagant dress, the exact state of my circulation.

In short, he seemed an awful lot like the genuine article.

“There you are, you old bastard,” said Charles happily, and sacré bleu, I realized then what I already knew, that the man before me was no delusion. That the Paris Ritz was the kind of place that could conjure up anyone it wanted.

“Stefan,” I said. “What a lovely surprise.”

(And the big trouble was, I think I meant it.)

First Movement (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

“Experience is simply the name

we give our mistakes.”

OSCAR WILDE

PEPPER (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

Palm Beach • 1966

1.

The Mercedes-Benz poses on the grass like a swirl of vintage black ink, like no other car in the world.

You’d never guess it to look at her, but Miss Pepper Schuyler—that woman right over there, the socialite with the golden antelope legs who’s soaking up the Florida sunshine at the other end of the courtyard—knows every glamorous inch of this 1936 Special Roadster shadowing the grass. You might regard Pepper’s pregnant belly protruding from her green Lilly shift (well, it’s hard to ignore a belly like that, isn’t it?) and the pastel Jack Rogers sandal dangling from her uppermost toe, and you think you have her pegged. Admit it! Lush young woman exudes Palm Beach class: What the hell does she know about cars?

Well, beautiful Pepper doesn’t give a damn what you think about her. She never did. She’s thinking about the car. She slides her gaze along the seductive S-curve of the right side fender, swooping from the top of the tire to the running board below the door, like a woman’s voluptuously naked leg, and her heart beats a quarter-inch faster.

She remembers what a pain in the pert old derrière it was to repaint that glossy fender. It had been the first week of October, and the warm weather wouldn’t quit. The old shed on Cape Cod stank of paint and grease, a peculiarly acrid reek that had crept right through the protective mask and into her sinuses and taken up residence, until she couldn’t smell anything else, and she thought, What the hell am I doing here? What the hell am I thinking?

Thank God that was all over. Thank God this rare inky-black 1936 Mercedes Special Roadster is now someone else’s problem, someone willing to pay Pepper three hundred thousand dollars for the privilege of keeping its body and chrome intact against the ravages of time.

The deposit has already been paid, into a special account Pepper set up in her own name. (Her own name, her own money: now, that was a glorious feeling, like setting off for Europe on an ocean liner with nothing but open blue seas ahead.) The rest will be delivered today, to the Breakers hotel where Pepper is staying, in a special-delivery envelope. Another delightful little big check made out in Pepper’s name. Taken together, those checks will solve all her problems. She’ll have money for the baby, money to start everything over, money to ignore whoever needs ignoring, money to disappear if she needs to, forever and ever. She’ll depend on no one. She can do whatever the hell she pleases, whatever suits Pepper Schuyler and—by corollary—Pepper Junior. She will toe nobody’s line. She will fear nobody.

So the only question left in Pepper’s mind, the only question that needs resolving, is the niggling Who?

Who the hell is this anonymous buyer—a woman, Pepper’s auction agent said—who has the dough and the desire to lay claim to Pepper’s very special Special Roadster, before it even reaches the public sales ring?

Not that Pepper cares who she is. Pepper just cares who she isn’t. As long as this woman is a disinterested party, a person who has her own reasons for wanting this car, nothing to do with Pepper, nothing to do with the second half of the magic equation inside Pepper’s belly, well, everything’s just peachy keen, isn’t it? Pepper will march off with her three hundred thousand dollars and never give the buyer another thought.

Pepper lifts a tanned arm and checks her watch. It’s a gold Cartier, given to her by her father for her eighteenth birthday, perhaps as a subtle reminder to start arriving the hell on time, now that she was a grown-up. It didn’t work. The party always starts when Pepper gets there, not before, so why should she care if she arrives late or early? Still, the watch has its uses. The watch tells her it’s twenty-seven minutes past twelve o’clock. They should be here any moment: Pepper’s auction agent and the buyer, to inspect the car and complete the formalities. If they’re on time, and why wouldn’t they be? By all accounts, the lady’s as eager to buy as Pepper is to sell.

Pepper tilts her head back and closes her eyes to the white sun. She can’t get enough of it. This baby inside her must have sprung from another religion, one that worshipped the gods in the sky or gained nourishment from sunbeams. Pepper can almost feel the cells dividing in ecstasy as she points herself due upward. She can almost feel the seams strain along her green Lilly shift, the dancing monkeys stretch their arms to fit around the ambitious creature within.

Well, that makes sense, doesn’t it? Like father, like child.

“Good afternoon.”

Pepper bolts upright. A small and slender woman stands before her, dark-haired, dressed in navy Capri pants and a white shirt, her delicate face hidden by a pair of large dark sunglasses. It’s Audrey Hepburn, or else her well-groomed Florida cousin.

“Good afternoon,” Pepper says.

The woman holds out her hand. “You must be Miss. Schuyler. My name is Annabelle Dommerich. I’m the buyer. Please, don’t get up.”

Pepper rises anyway and takes the woman’s hand. Mrs. Dommerich stands only a few inches above five feet, and Pepper is a tall girl, but for some reason they seem to meet as equals.

“I’m surprised to see you,” says Pepper. “I had the impression you wanted to remain anonymous.”

Mrs. Dommerich shrugs. “Oh, that’s just for the newspapers. Actually, I’ve been hugely curious to meet you, Miss Schuyler. You’re even more beautiful than your pictures. And look at you, blooming like a rose! When are you due?”

“February.”

“I’ve always envied women like you. When I was pregnant, I looked like a beach ball with feet.”

“I can’t imagine that.”

“It was a long time ago.” Mrs. Dommerich takes off her sunglasses to reveal a pair of large and chocolaty eyes. “The car looks beautiful.”

“Thank you. I had an expert helping me restore it.”

“You restored it yourself?” Both eyebrows rise, so elegant. “I’m impressed.”

“There was nothing else to do.”

Mrs. Dommerich turns to gaze at the car, shielding her brows with one hand. “And you found it in the shed on Cape Cod? Just like that, covered with dust? Untouched?”

“Yes. My sister-in-law’s house. It seemed to have been abandoned there.”

“Yes,” says Mrs. Dommerich. “It was.”

The grass prickles Pepper’s feet through the gaps in her sandals. Next to her, Mrs. Dommerich stands perfectly still, like she’s posing for a portrait, Woman Transfixed in a Crisp White Shirt. She talks like an American, in easy sentences, but there’s just the slightest mysterious tilt to her accent that suggests something imported, like the Chanel perfume that colors the air next to her skin. Though that skin is remarkably fresh, lit by a kind of iridescent pearl-like substance that most women spend fruitless dollars to achieve, Pepper guesses she must be in her forties, even her late forties. It’s something about her expression and her carriage, something that makes Pepper feel like an ungainly young colt, dressed like a little girl. Even considering that matronly bump that interrupts the youthful line of her figure.

At the opposite end of the courtyard, a pair of sweating men appear, dressed in businesslike wool suits above a pair of perfectly matched potbellies, neat as basketballs. One of them spots the two women and raises his hand in what Pepper’s always called a golf wave.

“There they are,” says Mrs. Dommerich. She turns back to Pepper and smiles. “I do appreciate your taking such trouble to restore her so well. How does she run?”

“Like a racehorse.”

“Good. I can almost hear that roar in my ears now. There’s no other sound like it, is there? Not like anything they make today.”

“I wouldn’t know, really. I’m not what you’d call an enthusiast.”

“Really? We’ll have to change that, then. I’ll pick you up from your hotel at seven o’clock and we’ll take her for a spin before dinner.” She holds out her hand, and Pepper, astonished, can do nothing but shake it. Mrs. Dommerich’s fingers are soft and strong and devoid of rings, except for a single gold band on the telling digit of her left hand, which Pepper has already noticed.

“Of course,” Pepper mumbles.

Mrs. Dommerich slides her sunglasses back in place and turns away.

“Wait just a moment,” says Pepper.

“Yes?”

“I’m just curious, Mrs. Dommerich. How do you already know how the engine sounds? Since it’s been locked away in an old shed all these years.”

“Oh, trust me, Miss Schuyler. I know everything about that car.”

There’s something so self-assured about her words, Pepper’s skin begins to itch, and not just the skin that stretches around the baby. The sensation sets off a chain reaction of alarm along the pathways of Pepper’s nerves: the dingling of tiny alarm bells in her ears, the tingling in the tip of her nose.

“And just how the hell do you know that, Mrs. Dommerich? If you don’t mind me asking. Why exactly would you pay all that money for this hunk of pretty metal?”

Mrs. Dommerich’s face is hidden behind those sunglasses, betraying not an ounce of visible reaction to Pepper’s impertinence. “Because, Miss Schuyler,” she says softly, “twenty-eight years ago, I drove for my life across the German border inside that car, and I left a piece of my heart inside her. And now I think it’s time to bring her home. Don’t you?” She turns away again, and as she walks across the grass, she says, over her shoulder, sounding like an elegant half-European mother: “Wear a cardigan, Miss Schuyler. It’s supposed to be cooler tonight, and I’d like to put the top down.”

2.

At first, Pepper has no intention of obeying the summons of Annabelle Dommerich. The check is waiting for her when she calls at the front desk at the hotel, along with a handwritten telephone message that she discards after a single glance. She has the doorman call her a taxi, and she rides into town to deposit the check in her account. The clerk’s face is expressionless as he hands her the receipt. She withdraws a couple hundred bucks, which she tucks into her pocketbook next to her compact and her cigarettes. When she returns to the hotel, she draws herself a bubble bath and soaks for an hour, sipping from a single glass of congratulatory champagne and staring at the tiny movements disturbing the golden curve of her belly. Thank God she hasn’t got any stretch marks. Coconut oil, that’s what her doctor recommended, and she went out and bought five bottles.

The water turns cool. Pepper lifts her body from the tub and wraps herself in a white towel. She orders a late room-service lunch and stands on the balcony, wrapped in her towel, smoking a cigarette. She considers another glass of champagne but knows she won’t go through with it. The doctor back on Cape Cod, a comely young fellow full of newfangled ideas, said to go easy on the booze. The doctor also said to go easy on the smokes, but you can’t do everything your doctor says, can you? You can’t give up everything, all at once, when you have already given up so much.

And for what? For a baby. His baby, of all things. So stupid, Pepper. You thought you were so clever and brave, you thought you had it all under control, and now look at you. All knocked up and nowhere to go.

The beach is bright yellow and studded with sunbathers before a lazy surf. Pepper reaches to tuck in her towel and lets it fall to the tiled floor of the balcony. No one sees her. She leans against the balcony rail, naked and golden-ripe, until her cigarette burns to a tiny stump in her hand, until the bell rings with her room-service lunch.

After she eats, she sets the tray outside her door and falls into bed. She takes a long nap, over the covers, and when she wakes up she slips into a sleeveless tunic-style cocktail dress, brushes her hair, and touches up her lipstick. Before she heads for the elevator, she takes a cardigan from the drawer and slings it over her bare shoulders.

3.

But the elevator’s stuck in the lobby. That was the trouble with hotels like the Breakers; there was always some Greek tycoon moving in, some sausage king from Chicago, and the whole place ground to a halt to accommodate his wife and kids and help and eighty-eight pieces of luggage. Afterward, he would tell his friends back home that the place wasn’t what it was cracked up to be, and the natives sure were unfriendly.

Pepper taps her foot and checks her watch, but the elevator is having none of it. She heads for the stairs.

On the one hand, you have the luxurious appointments of the Breakers, plush carpets and mirrors designed to show you off to your best advantage. On the other hand, you have the stairwell, like an escape from Alcatraz. Pepper’s spindly shoes rattle on the concrete floors; the bare incandescent bulbs appear at intervals as if to interrogate her. She has just turned the last landing, lobby escape hatch in sight, when a man comes into view, leaning against the door. He’s wearing a seersucker suit—a genuine blue-striped seersucker suit, as if men actually wore them anymore—and his arms are crossed.

For an instant, Pepper thinks of a platinum starlet, sprawled naked on her bedroom floor a few years back. Killed herself, poor bimbo, everyone said, shaking the sorrowful old head. Drugs, of course. A cautionary Hollywood tale.

“Nice suit,” says Pepper. “Are they making a movie out there?”

He straightens from the door and shoots his cuffs. “Miss Schuyler? Do you have a moment?”

“I don’t think so. Certainly not for strangers who lurk in stairwells.”

“I’m afraid I must insist.”

“I’m afraid you’re in my way. Do you mind stepping aside?”

In response, Captain Seersucker stretches his thick candy-stripe arm across the passage and places a hand against the opposite wall.

“Well, well,” says Pepper. “A nice beefy fellow, aren’t you? How much do they hire you out for? Or do you do it just for the love of sport?”

“I’m just a friend, Miss Schuyler. A friend of a friend who wants to talk to you, that’s all, nice and friendly. So you’re going to have to come with me.”

Pepper laughs. “You see, that’s the trouble with you musclemen. Not too much in the noggin, is there?”

“Miss Schuyler—”

“Call me Pepper, Captain Seersucker. Everyone else does.” She holds out her hand, and when he doesn’t take it, she pats his cheek. “A big old lug, aren’t you? Tell me, what do you do when the quiz shows come on the TV? Do you just stare all blank at the screen, or do you try to learn something?”

“Miss Schuyler—”

“And now you’re getting angry with me. Your face is all pink. Look, I don’t hold it against you. We can’t all be Einstein, can we? The world needs brawn as well as brain. And the girls certainly don’t mind, do they? I mean, what self-respecting woman wants a man hanging around who’s smarter than she is?”

“Look here—”

“Now, just look at that jaw of yours, for example. So useful! Like a nice square piece of granite. I’ll bet you could crush gravel with it in your spare time.”

He lifts his hand away from the wall and makes to grab her, but Pepper’s been waiting for her chance, and she ducks neatly underneath his arm, pregnancy and all, and brings her knee up into his astonished crotch. He crumples like a tin can, lamenting his injured manhood in loud wails, but Pepper doesn’t waste a second gloating. She throws open the door to the lobby and tells the bellboy to call a doctor, because some poor oaf in a seersucker suit just tripped on his shoelaces and fell down the stairs.

4.

“I thought you wouldn’t come,” says Mrs. Dommerich, as Pepper slides into the passenger seat of the glamorous Mercedes. Every head is turned toward the pair of them, but the lady doesn’t seem to notice. She’s wearing a wide-necked dress of midnight-blue jacquard, sleeves to the elbows and hem to the knees, extraordinarily elegant.

“I wasn’t going to. But then I remembered what a bore it is, sitting around my hotel room, and I came around.”

“I’m glad you did.”

Mrs. Dommerich turns the ignition, and the engine roars with joy. Cars like this, they like to be driven, Pepper’s almost-brother-in-law said, the first time they tried the engine, and at the time Pepper thought he was crazy, talking about a machine as if it were a person. But now she listens to the pitch of the pistons and supposes he was probably right. Caspian usually was, at least when it came to cars.

“I guess you know how to drive this thing?” Pepper says.

“Oh, yes.” Mrs. Dommerich puts the car into gear and releases the clutch. The car pops away from the curb like a hunter taking a fence. Pepper notices her own hands are a little shaky, and she places her fingers securely around the doorframe.

Just as the hotel entrance slides out of view, she spots a pair of men loitering near the door, staring as if to bore holes through the side of Pepper’s head. Not locals; they’re dressed all wrong. They’re dressed like the man in the stairwell, like some outsider’s notion of how you dressed in Palm Beach, like someone told them to wear pink madras and canvas deck shoes, and they’d fit right in.

And then they’re gone.

Pepper ties her scarf around her head and says, in a remarkably calm voice, “Where are we going?”

“I thought we’d have dinner in town. Have a nice little chat. I’d like to hear a little more about how you found her. What it was like, bringing her back to life.”

“Oh, it’s a girl, is it? I never checked.”

“Ships and automobiles, my dear. God knows why.”

“You know,” says Pepper, drumming her fingers along the edge of the window glass, “don’t take this the wrong way, but I can’t help noticing that you two seem to be on awfully familiar terms, for a nice lady and a few scraps of old metal.”

“I should be, shouldn’t I? I paid an awful lot of money for her.”

“For which I can’t thank you enough.”

“Well, I couldn’t let her sit around in some museum. Not after all we’ve been through together.” She pats the dashboard affectionately. “She belongs with someone who loves her.”

Pepper shakes her head. “I don’t get it. I don’t see how you could love a car.”

“Someone loved this car, to put it back together like this.”

“It wasn’t me. It was Caspian.”

“Who’s Caspian?”

Pepper opens her pocketbook and takes out her compact. “We’ll just say he’s a friend of my sister’s, shall we? A very good friend. Anyway, he’s the enthusiast. He couldn’t stand watching me try to put it together myself.”

“I’m eternally grateful. I suppose he knows a lot about German cars?”

“It turns out he was an army brat. They lived in Germany when he was young, right after the war, handing out retribution with one hand and Hershey bars with the other.”

Mrs. Dommerich swings the heavy Mercedes around a corner, on the edge of a nickel. Pepper realizes that the muscles of her abdomen are clenched, and it’s nothing to do with the baby. But there’s no question that Mrs. Dommerich knows how to drive this car. She drives it the way some people ride horses, as if the gears and the wheels are extensions of her own limbs. She may not be tall, but she sits so straight it doesn’t matter. Her scarf flutters gracefully in the draft. She reaches for her pocketbook, which lies on the seat between them, and takes out a cigarette with one hand. “Do you mind lighting me?” she asks.

Pepper finds the lighter and brings Mrs. Dommerich’s long, thin Gauloise to life.

“Thank you.” She blows a stream of smoke into the wind and holds out the pack to Pepper. “Help yourself.”

Pepper eyes the tempting little array. Her shredded nerves jingle in her ears. “Maybe just one. I’m supposed to be cutting back.”

“I didn’t start until later,” Mrs. Dommerich says. “When my babies were older. We started going out more, to cocktail parties and things, and the air was so thick I thought I might as well play along. But it never became a habit, thank God. Maybe because I started so late.” She takes a long drag. “Sometimes it takes me a week to go through a single pack. It’s just for the pure pleasure. It’s like sex, you want to be able to take your time and enjoy it.”

Pepper laughs. “That’s a new one on me. I always thought the more, the merrier. Sex and cigarettes.”

“My husband never understood, either. He smoked like a chimney, one after another, right up until the day he died.”

“And when was that?”

“A year and a half ago.” She checks the side mirror. “Lung cancer.”

“I’m sorry.”

They begin to mount the bridge to the mainland. Mrs. Dommerich seems to be concentrating on the road ahead, to the flashing lights that indicates the deck is going up. She rolls to a stop and drops the cigarette from the edge of the car. When she speaks, her voice has dropped an octave, to a rough-edged husk of itself.

“I used to try to make him stop,” she says. “But he didn’t seem to care.”

5.

They eat at a small restaurant off Route 1. The owner recognizes Mrs. Dommerich and kisses both her cheeks. They chatter together in French for a moment, so rapidly and colloquially that Pepper can’t quite follow. Mrs. Dommerich turns and introduces Pepper—my dear friend Miss Schuyler, she calls her—and the man seizes Pepper’s belly in rapture, as if she’s his mistress and he’s the guilty father.

“So beautiful!” he says.

“Isn’t it, though.” Pepper removes his hands. Since the beginning of the sixth month, Pepper’s universe has parted into two worlds: people who regard her pregnancy as a kind of tumor, possibly contagious, and those who seem to think it’s public property. “Whatever will your wife say when she finds out?”

“Ah, my wife.” He shakes his head. “A very jealous woman. She will have my head on the carving platter.”

“What a shame.”

When they are settled at their table, supplied with water and crusty bread and a bottle of quietly expensive Burgundy, Mrs. Dommerich apologizes. The French are obsessed with babies, she says.

“I thought they were obsessed with sex.”

“It’s not such a stretch, is it?”

Pepper butters her bread and admits that it isn’t.

The waiter arrives. Mrs. Dommerich orders turtle soup and sweetbreads; Pepper scans the menu and chooses mussels and canard à l’orange. When the waiter sweeps away the menus and melts into the atmosphere, a pause settles, the turning point. Pepper drinks a small sip of wine, folds her hands on the edge of the table, and says, “Why did you ask me to dinner, Mrs. Dommerich?”

“I might as well ask why you agreed to come.”

“Age before beauty,” says Pepper, and Mrs. Dommerich laughs.

“That’s it, right there. That’s why I asked you.”

“Because I’m so abominably rude?”

“Because you’re so awfully interesting. As I said before, Miss Schuyler. Because I’m curious about you. It’s not every young debutante who finds a vintage Mercedes in a shed at her sister’s house and restores it to its former glory, only to put it up for auction in Palm Beach.”

“I’m full of surprises.”

“Yes, you are.” She pauses. “To be perfectly honest, I wasn’t going to introduce myself at all. I already knew who you were, at least by reputation.”

“Yes, I’ve got one of those things, haven’t I? I can’t imagine why.”

“You have. I like to keep current on gossip. A vice of mine.” She smiles and sips her wine, marrying vices. “The sparky young aide in the new senator’s office, perfectly bred and perfectly beautiful. They were right about that, goodness me.”

Pepper shrugs. Her beauty is old news, no longer interesting even to her.

“Yes, exactly.” Mrs. Dommerich nods. Her hair is cut short, curling around her ears, a stylish frame for the heart-shaped, huge-eyed delicacy of her face. A few silver threads catch the light overhead, and she hasn’t tried to hide them. “You caused a real stir, you know, when you started working in the senator’s office last year. I suppose you know that. Not just that you’re a walking fashion plate, but that you were good at your job. You made yourself essential to him. You had hustle. There are beautiful women everywhere, but they don’t generally have hustle. When you’re beautiful, it’s ever so much easier to find a man to hustle for you.”

“Yes, but then you’re stuck, aren’t you? It’s his rules, not yours.”

The skin twitches around Mrs. Dommerich’s wide red mouth.

“True. That’s what I thought about you, when I saw you. I saw you were expecting, pretty far along, and all of a sudden I understood why you fixed up my car and sold it to me for a nice, convenient fortune. I understood perfectly.”

“Oh, you did, did you?” Pepper lifts her knife and examines her reflection. A single blue Schuyler eye stares back at her, turned up at the corner like the bow of an especially elegant yacht. “Then why the hell were you still curious enough to invite me out?”

The waiter arrives solemnly with the soup and the mussels. Mrs. Dommerich waits in a pod of elegant impatience while he sets each dish exactly so, flourishes the pepper, asks if there will be anything else, and is dismissed. She lifts her spoon and smiles.

“Because, my dear, I can’t wait to see what you do next.”

6.

Pepper lights another cigarette after dinner, while Mrs. Dommerich drives the Mercedes north along the A1A. For air, she says. Pepper doesn’t care much about air, one way or another, but she does care about those two men hanging around the entrance of the hotel before they left. She can handle one overgrown oaf in a stairwell, maybe, but two more was really too much.

So Pepper says okay, she could use some air. Let’s take a little drive somewhere. She draws the smoke pleasantly into her lungs and breathes it out again. Air. To the right, the ocean ripples in and out of view, phosphorescent under a swollen November moon, and as the miles roll under the black wheels Pepper wonders if she’s being kidnapped, and whether she cares. Whether it matters if Mrs. Dommerich acts for herself or for someone else.

He was going to track her down anyway, wasn’t he? Sooner or later, the house always won.

Pepper used to think that she was the house. She has it all: family, beauty, brains, moxie. You think you hold all the cards, and then you realize you don’t. You have one single precious card, and he wants it back.

And suddenly three hundred thousand dollars doesn’t seem like much security, after all. Suddenly there isn’t enough money in the world.

Pepper stubs out the cigarette in the little chrome ashtray. “Where are we going, anyway?”

“Oh, there’s a little headland up ahead, tremendous view of the ocean. I like to park there sometimes and watch the waves roll in.”

“Sounds like a scream.”

“You might try it, you know. It’s good for the soul.”

“I have it on good authority, Mrs. Dommerich—from a number of sources, actually—that I haven’t got one. A soul, I mean.”

Mrs. Dommerich laughs. They’re speaking loudly, because of the draft and the immense roar of the engine. She bends around another curve, and then the car begins to slow, as if it already knows where it’s going, as if it’s fate. They pull off the road onto a dirt track, lined by reeds a yard high, and such is the Roadster’s suspension that Pepper doesn’t feel a thing.

“I’m usually coming from the north,” says Mrs. Dommerich. “We have a little house by the coast, near Cocoa Beach. When we first moved here from France, we wanted a quiet place where we could hide away from the world, and then of course the air-conditioning came in, and the world came to us in droves.” She laughs. “But by then it didn’t seem to matter. The kids loved it here too much, we couldn’t sell up. As long as I could see the Atlantic, I didn’t care.”

The reeds part and the ocean opens up before them. Mrs. Dommerich keeps on driving until they reach the dunes, silver and black in the moonlight. Pepper smells the salt tide, the warm rot. The car rolls to a stop, and Mrs. Dommerich cuts the engine. The steady rush of water reaches Pepper’s ears.

“Isn’t it marvelous?” says Mrs. Dommerich.

“It’s beautiful.”

Mrs. Dommerich finds her pocketbook and takes out a cigarette. “We can share,” she says.

“I’ve already reached my limit.”

“If we share, it doesn’t count. Halves don’t count.”

Pepper takes the cigarette from her fingers and examines it.

Mrs. Dommerich settles back and stares through the windshield. “Do you know what I love most about the ocean? The way the water’s all connected. The bits and pieces have different names, but really it’s all one vast body of salt water, all the way around the earth. It’s as if we’re touching Europe, or Africa, or the Antarctic. If you close your eyes, you can feel it, like it’s right there.”

Pepper hands back the cigarette. “That’s true. But I don’t like to close my eyes.”

“You’ve never made an act of faith?”

“No. I like to rely on myself.”

“So I see. But you know, sometimes it’s not such a bad thing. An act of faith.”

Pepper snatches the cigarette and takes a drag. She blows the smoke back out into the night and says, “So what’s your game?”

“My game?”

“Why are you here? Obviously you know a thing or two about me. Did he send you?”

“He?”

“You know who.”

“Oh. The father of your baby, you mean.”

“You tell me.”

Mrs. Dommerich lifts her hands to the steering wheel and taps her fingers against the lacquer. “No. Nobody sent me.”

Pepper tips the ash into the sand and hands back the cigarette.

“Do you believe me?” Mrs. Dommerich asks.

“I don’t believe in anything, Mrs. Dommerich. Just myself. And my sisters, too, I guess, but they have their own problems. They don’t need mine on top of it all.”

Mrs. Dommerich spreads out her hands to examine her palms. “Then let me help instead.”

Pepper laughs. “Oh, that’s a good one. Very kind of you.”

“I mean it. Why not?”

“Why not? Because you don’t even know me.”

“There’s no law against helping strangers.”

“Well, I certainly don’t know a damned thing about you, except that you’re rich and your husband died last year, and you have children and love the ocean. And you drove this car across Germany thirty years ago—”

“Twenty-eight.”

“Twenty-eight. And even if that’s all true, it’s not much to go on.”

“Isn’t it? Marriages have been made on less knowledge. Happy ones.”

That’s an odd thing to say, Pepper thinks, and she hears the words echoing: an act of faith. Well, that explains it. Maybe Mrs. Dommerich is one of those sweet little fools who thinks the world is a pretty place to live, filled with nice people who love you, where everything turns out all right if you just smile and tap your heels together three times.

Or maybe it’s all an act.

A little gust of salt wind comes off the ocean, and Pepper snuggles deeper into her cardigan. Mrs. Dommerich finishes the cigarette and smashes it out carefully into the ashtray, next to Pepper’s stub from the ride up. She reaches into the glove compartment and draws out a small thermos container. “Coffee?” she asks, unscrewing the cap.

“Where did you get coffee?”

“I had Jean-Louis fill it up for me before we left.”

Pepper takes the small plastic cup. The coffee is strong and still hot. They sit quietly, sipping and gazing, sharing the smell of the wide Atlantic. The ocean heaves and rushes before them, unseen except for the long white crests of the rollers, picked out by the moon.

Mrs. Dommerich asks: “If I were to guess who the father is, would I be right?”

“Probably.”

She nods. “I see.”

Pepper laughs again. “Isn’t it hilarious? Who’d have thought a girl like me could be so stupid? It isn’t as if I didn’t have my eyes open. I mean, I knew all the rumors, I knew I might just be playing with a live grenade.”

“But you couldn’t resist, could you?”

“The oldest story in the book.”

The baby stirs beneath Pepper’s heart, stretching out a long limb to test the strength of her abdomen. She puts her hand over the movement, a gesture of pregnancy that used to annoy her, when it was someone else’s baby.

Mrs. Dommerich speaks softly. “Because he was irresistible, wasn’t he? He made you think there was no other woman in the world, that this thing you shared was more sacred than law.”

“Something like that.”

Mrs. Dommerich pours out the dregs of her coffee and wipes out the cup with a handkerchief. “I’m serious, you know. It’s the real reason I wanted to speak to you. To help you, if I can.”

“You don’t say.”

Mrs. Dommerich pauses. “You know, there are all kinds of heroes in the world, Miss Schuyler, though I know you don’t believe in that, either. And you’re a fine girl, underneath all that cynical bluster of yours, and if this man wasn’t what you hoped, I assure you there will be someone else who is.”

Pepper looks out at the ocean and thinks about how wrong she is. There will never be someone else; how could there be? There will be men, of course. Pepper’s no saint. But there won’t be someone else. The thing about Pepper, she never makes the same mistake twice.

She folds her arms atop her belly and says, “Don’t hold your breath.”

Mrs. Dommerich laughs and gets out of the car. She stretches her arms up to the night sky, and the moon catches the glint in her wedding ring. “What a beautiful night, isn’t it? Not too cool, after all. I can’t bear the summers here, but it’s just the thing to cheer me up in November.”

“What’s wrong with November?”

Mrs. Dommerich doesn’t answer. She goes around the front of the car and settles herself on the hood, tucking up her knees under her chin. After a moment, Pepper joins her, except that Pepper’s belly sticks out too far for such a gamine little pose, so she removes her sandals, stretches her feet into the sand, and leans against the familiar warm hood instead.

“Are we just going to sit here forever?” Pepper asks.

Mrs. Dommerich wraps her arms around her legs and doesn’t speak. Pepper wants to tap her head like an eggshell, to see what comes out. What’s her story? Why the hell is she bothering with Pepper? Women don’t usually bother with Pepper, and she doesn’t blame them. Look what happens when you do. Pepper fertilizes her womb with your husband.

“Well?” Pepper says at last, because she’s not the kind of girl who waits for you to pull yourself together. “What are you thinking about?”

Mrs. Dommerich starts, as if she’s forgotten Pepper is there at all. “Oh, I’m sorry. Ancient history, really. Have you ever been to the Paris Ritz?”

Pepper toes the sand. “Once. We went to Europe one summer, when I was in college.”

“Well, I was there in the summer of 1937, when the Ritz was the center of the universe. Everybody was there.” She stands up and dusts off her dress. “Anyway. Come along, my dear.”

“Wait a second. What happened at the Ritz?”

“Like I said, it’s ancient history. Water under the bridge.”

“You were the one who brought it up.”

Mrs. Dommerich folds her arms and stares at the ocean. Pepper’s toe describes a square in the sand and tops it off with a triangular roof. She tries to recall the Ritz, but the grand hotels of Europe had all looked alike after a while. Wasn’t that a shame? All that effort and expense, and in a week or two they all blurred together.

Still, she remembers a bit. She remembers glamour and a glorious long bar, a place where Pepper could do business. What kind of business had sweet, elegant Mrs. Dommerich done there?

Just as Pepper gives up, just as she reaches downward to thread her sandals back over her toes, Mrs. Dommerich turns away from the ocean, and you’d think the moon had stuck in her eyes, they’re so bright.

“There was this party there,” she says. “A going-away party at the Ritz for an American who was moving back to New York. It was the kind of night you never forget.”

ANNABELLE (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

Antibes • 1935

1.

But long before the Ritz, there was the Côte d’Azur.

My father had used the last of Mummy’s money to lease his usual villa for the summer, perched on a picturesque cliff between Antibes and Cannes, and such was the lingering glamor of his face and his title that everybody came. There were rich American artists and poor English aristocrats; there was exiled Italian royalty and ambitious French bourgeoisie. To his credit, my father didn’t discriminate. He welcomed them all. He gave them crumbling rooms and moderately fresh linens, cheap food and good wine, and they kept on coming in their stylish waves, smoking cigarettes and getting drunk and sleeping with one another. Someone regularly had to be saved from drowning.

Altogether it was a fascinating summer for a young lady just out of a strict convent school in the grimmest possible northwest corner of Brittany. The charcoal lash of Biscay storms had been replaced by the azure sway of the Mediterranean; the ascetic nuns had been replaced by decadent Austrian dukes. And there was my brother, Charles. I adored Charles. He was four years older and terribly dashing, and for a time, when I was young, I actually thought I would never, ever get married because nobody could be as handsome as my brother, because all other men fell short.

He invited his own guests, my brother, and a few of them were here tonight. In the way of older brothers, he didn’t quite worship me the way I worshipped him. I might have been a pet lamb, straying in my woolly innocence through his fields, to be shooed gently away in case of wolves. They held their own court (literally: they gathered in the tennis courts at half past eleven in the morning for hot black coffee and muscular Turkish cigarettes) and swam in their own corner of the beach, down the treacherous cliff path: naked, of course. There were no women. Charles’s retreat was run along strictly fraternal lines. If anyone fancied sex, he came back to the house and stalked one or another of my father’s crimson-lipped professional beauties, so I learned to stay away from the so-called library and the terrace (favored hunting grounds) between the hours of two o’clock in the afternoon and midnight, though I observed their comings and goings the way other girls read gossip magazines.

Which is all a rather long way of explaining why I happened to be lying on the top of the garden wall, gazing quietly toward the lanterns and the female bodies in their shimmering dresses, the crisp drunk black-and-white gentlemen, on the moonless evening they brought the injured Jew to the house.

At half past ten, shortly before the Jew’s arrival, I became aware of an immense heat taking shape in the air nearby. I waited for this body to carry on into the garden, or the scrubby sea lawn sloping toward the cliffs, but instead it lingered quietly, smelling of liquor and cigarettes. Without turning my head, I said, in English, “I’m sorry. Am I in your way?”

“I beg your pardon. I did not wish to disturb you.” The English came without hesitation, a fluid intermingling of High German and British public schools, delivered in a thick bass voice.

I told him, without turning my head, that he hadn’t. I knew how to kick away these unwanted advances from my father’s accidental strays. (The nuns, remember.)

“Very good,” he said, but he didn’t leave.

He occupied a massive hole in the darkness behind me, and that—combined with the massive voice, the hint of dialect—suggested that this man was Herr von Kleist, an army general and Junker baron who had arrived three days ago in a magnificent black Mercedes Roadster with a single steamer trunk and no female companion. How he knew my father, I couldn’t say; not that prior acquaintance with the host was any requirement for staying at the Villa Vanilla. (That was my name for the house, in reference to the sandy-pale stone with which it was built.) I had spoken to him a few times, in the evenings before dinner. He always sat alone, holding a single small glass of liquor.

I rose to a sitting position and swung my feet down from the wall. “I’ll leave you to yourself, then,” I said, and I prepared to jump down.

“No, please.” He waved his hand. “Do not stir yourself.”

“I was about to leave anyway.”

“No, you mistake me. I only came to see if you were well. I saw you steal out here and lie on the garden wall.” He gestured again. “I hope you are not unwell.”

“I’m quite well, thank you.”

“Then why are you here, alone?”

“Because I like to be alone.”

He nodded. “Yes, of course. This is what I thought about you, when you were playing your cello for us the other night.”

He was dressed in a precise white jacket and tie, making him seem even larger than he did by day, and unlike the other guests he had no cigarette with him, no glass of some cocktail or another to occupy his hands, though I smelled both in the air surrounding him. The moon was new, and I couldn’t see his face, just the giant outline of him, the smudge of shadow against the night. But I detected a slight nervousness, a particle of anxiety lying between me and the sea. I’d seen many things at the Villa Vanilla, but I hadn’t seen nervousness, and it made me curious.

“Really? Why did you think that?”

“Because—” He stopped and switched to French. “Because you are different from the others here. You are too young and new. You shouldn’t be here.”

“None of us should be here, really. It is a great scandal, isn’t it?”

“But you particularly. Watching this.” Another gesture, this time at the terrace on the other side of the wall, and the shimmering figures inside it.

“Oh, I’m used to that.”

“I’m very sorry to hear that.”

“Why should you be sorry? You’re a part of it, aren’t you? You came here willingly, unlike me, who simply lives here and can’t help it. I expect you know what goes on, and why. I expect you’re here for your share.”

He hesitated. There was a flash of light from the house, or perhaps the driveway, and it lit the top of his head for an instant. He had an almost Scandinavian cast to him, this baron, so large and fair. (I pictured a Viking longboat invading some corner of Prussia, generations ago.) His hair was short and bristling and the palest possible shade of blond; his eyes were the color of Arctic sea ice. I thought he was about forty, as old as the world. “May I sit down?” he asked politely.

“Of course.”

I thought he would take the bench, but instead he placed his hands on the wall, about five feet down from me, and hoisted his big body atop as easily as if he were mounting a horse.

“How athletic of you,” I said.

“Yes. I believe firmly in the importance of physical fitness.”

“Of course you do. Did you have something important to tell me?”

He stared toward Africa. “No.”

Someone laughed on the terrace behind us, a high and curdling giggle cut short by the delicate smash of crystal. Neither of us moved.

Herr von Kleist sat still on the brink of the wall. I didn’t know a man that large could have such perfect control over his limbs. “My friend the prince, your father, I saw him quite by chance last spring, at the embassy in Paris. He told me that I must come to his villa this summer, that I am in need of sunshine and amitié. I thought perhaps he was right. I am afraid, in my inexperience, I did not guess the meaning of his word amitié.”

“Your inexperience?” I said dubiously.

“I have never been to a place like this. Like the void left behind by an absence of imagination, which they are attempting, in their wretchedness and ignorance, to fill with vice.”

“Yes, you’re right. I’ve just been thinking exactly the same thing.”

“My wife died eleven years ago. That is loss. That is a void left behind. But I try to fill that loss with something substantial, with work and the raising of our children.”

What on earth did you say to a thing like that? I ventured: “How many children do you have?”

“Four,” he said.

I waited for him to elaborate—age, sex, height, education, talents—but he did not. I stared down at the gossamer in my lap and said, “Where are they now?”

“With my sister. She was the one who insisted I go, and so I did. I regretted it the instant I walked through the door. There was a woman in the hall, a dark-haired woman, and she was smoking a cigarette and using the most unkempt language.”

“Probably Mrs. Henderson. She’s desperately rich and miserable. An American. She sleeps with everybody, even the servants.”

“It grieves me to hear this.”

“I’m afraid it’s true.”

“No, not that it’s true. I do not give a damn—pardon, Mademoiselle—about Mrs. Henderson. It grieves me that you know this about her. That your family would allow you under the same roof as such a woman as that.”

“Oh, it’s not as bad as that. My father doesn’t allow me to mingle very much with his guests, except to entertain them with my cello after dinner. He doesn’t know what to do with me at all, really, since I left Saint Cecilia’s, and I’m too old for a governess.”

“He ought to send you to live with a relative.”

“I would run away. I’d return here.”

“Why? You will pardon my curiosity. Why, when you are not like them?”

“Why not? I’m like a scientist, studying bugs. I find them fascinating, even if I don’t mean to turn into a mosquito myself.”

Herr von Kleist had placed his hands on his knees, and as large as his knees were, his hands dwarfed them. “Mosquitoes. Very good,” he said gravely. “Yes, this is exactly what I imagined about you, when I saw you lying on the garden wall just now, observing the mosquitoes.”

We had switched back into English at some point, I couldn’t remember when.

I said, “Really, you shouldn’t be here. You should go home to your children.”

He made another one of his sighs, weary of everything. “You are the one who should leave. There is not much hope for us, but you can still be saved. This is not the place for you.”

I jumped down from the wall and dusted the grit from my hands. “I’d say there’s plenty of hope for you. You seem like a decent man. Anyway, this is the only place I know, other than the convent.”

“Then go back to your convent.”

I was about to laugh, and I realized he was serious. At least his voice was serious, and his eyes, which were sad and invisible in the darkness. “But I don’t want to go back.”

“No, of course you do not. You want to live. You are how old?”

“Nineteen.”

He made a defeated noise and slid down from the wall. “You think I am ancient.”

“No, not at all,” I lied.

“I’m thirty-eight. But that does not matter.” He picked my hand from my side and kissed it. “It is you who matter.”

He was drunk, of course. I realized it now. He was one of those lucky fellows who held it perfectly, without slurring a single word, but he was drunk nonetheless. There was the slightest waver in his titanic frame as he stood before me, engulfing my fingers between his two leathery palms, and there was that waft of liquor I’d noticed from the beginning. Who could blame him? It took such an unlikely amount of moral resolve to remain sober at the Villa Vanilla.

When I didn’t speak, he moved his heavy head in a single nod. “Yes. It is better this way. Nothing valuable is ever gained in haste.”

“Quite true,” someone said, but it wasn’t me. It was my brother, Charles, coming up behind me like a cat in the night, and before either of us had time to reflect on the silent surprise of his appearance, he had pried my hand from the grasp of Herr von Kleist and begged the general’s forgiveness.

An urgent matter had arisen, and he needed to borrow his sister for a moment.

2.

“Borrow me?” I jogged to keep up as my brother’s long legs tore the scrubby grass between the garden and the cliffs. “Are you short for poker?”

“Of course not.” He yanked the cigarette stub from his mouth and tossed it on the ground, into a patch of gravel. “What the hell were you doing with that Nazi?”

“Nazi? He’s a Nazi?”

“They’re all Nazis now, aren’t they? Pay attention, it’s the cliff.”

I wasn’t dressed for climbing. I gathered up my skirts in one hand. We started down the path, over the lip of the cliff, and the sea crashed in my ears. I followed the flash of Charles’s shoes just ahead. “What’s the hurry?” I asked.

“Just be quiet.”

The last of the light from the house had dissolved, and I began to stumble in the absolute blackness of the night. I had only the faint ghostliness of Charles’s white shirt—he had somehow shed his dinner jacket—to guide me, as it jerked and jumped about and nearly disappeared in the space before me. The toe of my slipper found a rock, and I staggered to the ground.

“What’s the matter with you?” Charles said.

“I can’t see.”

He swore and fumbled in his pockets, and a second later a match struck against the edge of a box and hissed to life. “My God,” I said, staring at Charles’s face in the tiny yellow glow. “Is that blood?”

He touched his cheek. “Probably. Look around. Get your bearings.”

I looked down the slope of the cliff, the familiar path dissolving into the oily night. “Yes. All right.”

The match sizzled out against his fingers, and he dropped it into the rocks and took my hand. “Let’s go. Try to keep quiet, will you?”

I knew exactly where I was now. I could picture each stone, each twist in the jagged path. Inside the grip of Charles’s hand, my fingers tingled. Something was up, something extraordinary—so extraordinary, my brother was actually drawing me under the snug shelter of his confidence. Like when we were children, before Mummy died, before we returned to France and went our separate ways: me to the convent, my brother to the École Normale in Paris. That was when the curtain had come down. I was no longer his co-conspirator.

But I remembered how it was. My blood remembered: racing down my limbs, racing up to my brain like a cleansing bath. Come down to the beach, I’ve found something, Charles would say, and we would run hand in hand to the gritty boulder-strewn cove near the lighthouse, where he might show me an old blue glass bottle that had washed up onshore and surely contained a coded message (it never did), or a mysterious dead fish that must—equally surely—represent an undiscovered species (also never); and once, best of all, there was a bleached white skeleton, half articulated, its grinning skull exactly the size of Charles’s spread hand. I had thought, We’re in trouble now, someone will find out, someone will sneak into the house and kill us, too, to eliminate the witnesses; at the same time, I had cast about for the glimpse of wood that must be lying half hidden in the nearby sand, the treasure chest that this skeleton had guarded with his life.

Now, as I stumbled faithfully down the cliff path in Charles’s wake, and my eyes so adjusted to the darkness that I began to pick out the white tips of the waves crashing on the beach, the rocks returning the starlight, I wondered what bleached white skeleton he had found for me tonight.

And then the path fell into the sand, and Charles was tugging me through the dunes with such strength that my slippers were sucked away from my feet. We made for the point on the eastern end of the beach, where the sea curled around a finger of cliff and formed a slight cove on the other side. There was just enough shelter from the current for a small boathouse and a launch, which the guests sometimes used to ferry back and forth to the yachts in Cannes or Antibes. I saw the roof now, a gray smear in the starlight. Charles plunged straight toward it, running now. The sand flew from his feet. Just before he ducked through the doorway, he stopped and turned to me.

“You did say you nursed in a hospital, right? At the convent? I’m not imagining things?”

“What? Yes, every day, after—”

“Good.” He took my hand and pulled me inside.

There were four of them there, Charles’s friends, two of them still in their dinner jackets and waistcoats. An oil lantern sat on the warped old planks of the deck, next to the nervously bobbing launch, spreading just enough light to illuminate the fifth man in the boathouse.

He sat slumped against the wall, and his bare chest was covered in blood. He lifted his head as I came in—the chin had been tucked into the hollow of his clavicle—and he said, in deep German-accented English, much like the voice of Herr von Kleist, only more slurred and amused: “This is your great plan, Créouville?”

3.

But his chest wasn’t injured. As I cried out and fell to my knees at his side, I saw that he was holding a thick white wad to his thigh, around which a makeshift tourniquet had already been applied, and that the white wad—a shirt, I determined—was rapidly filling with blood, like the discarded red shirts next to his knee.

“Actually, it seems to be getting better,” he said.

I adjusted the tourniquet—it was too loose—and lifted away the shirt. A round wound welled instantly with blood. I said, incredulous: “But it’s a—”

“Gunshot,” he said.

I pressed the shirt back into the wound and called for whisky.

“I like the way you think,” said the wounded man.

“It’s not to drink. It’s to clean the wound. How long ago did this happen?”

“About twenty minutes. Right, boys?”

There was a general murmur of agreement, and a bottle appeared next to my hand. Gin, not whisky. I lifted away the shirt. The flow of blood had already slowed. “This will sting,” I said, and I tilted the bottle to allow a stream of gin on the torn flesh.

I was expecting a howl, but the man only grunted and gripped the side of the leg. “He needs a doctor, as quickly as possible,” I said to the men. “Has someone telephoned Dr. Duchamps?”

There was no reply. I put my fingers under the injured man’s chin and peered into his eyes. His pupils were dilated, but not severely; he met my gaze and followed me as I turned my face from one side to the other. I glanced back at Charles. “Well? Doctor? Is he on his way?”

Charles crouched next to me. “No.”

“Why not?”

“Too much fuss. There’s someone meeting you on the ship.”

“Ship? What ship?”

The injured man said, “My ship.”

“You’re going with him,” said Charles. “You can still drive the launch, can’t you?”

“What?”

“You’re the only one who can do it. The rest of us have to stay here.”

“What? Why?”

“Cover,” said the injured man, through his gritted teeth.

I looked back down at the wound, which was now only seeping. Probably the bullet had only nicked the femoral artery, otherwise he would have been dead by now. He was a large man—not as large as Herr von Kleist, but larger than my brother—and he had plenty of blood to spare. Still, it was a close thing. My brain was sharp, but my fingers were trembling as I pressed the shirt back down. Another fraction of an inch. My God. “I don’t have the slightest idea what you mean,” I said, “and why not one of you perfectly able-bodied men can help me get this man to safety, but we don’t have a minute to waste arguing. Give him a fresh shirt. If he can hold it to his leg himself, I can take him to his damned yacht. It is a yacht, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Mademoiselle,” the man said humbly.

“Of course it is. And if the police catch up with us, what am I to say?”

“That you know nothing about it, of course.”

I took the fresh shirt from Charles’s hand and replaced the old; I took the man’s large limp hand and pressed it to the makeshift bandage. “I’ll take the gin. Charles, you put him in the launch.”

“You see?” said Charles. “I told you she was a sport.”

4.

On the launch, I took pity on the man and gave him the bottle of gin, while I steered us around the tip of the Cap d’Antibes and west toward Cannes, where his yacht was apparently moored. He took a grateful swig and tilted his head to the stars. The lantern sat at the bottom of the boat, so as not to be visible from shore.

“You are very beautiful,” he said.

“Stop. You’re not flirting with me, please. You came three millimeters away from death just now.” The draft was cool and salty; it stung my cheeks, or maybe I was only blushing.

“No, I am not flirting. But you are beautiful. A statement of fact.”

I peered into the dark sea, seeking out the distant harbor lights, smaller than stars on the horizon. The water was calm tonight, only a hint of chop. As if God himself were watching over this man.

“Am I allowed to ask your name?” I said.

He hesitated. “Stefan.”

“Stefan. Is that your real name?”

“If you call me Stefan, Mademoiselle, I will answer you.”

“I see. And what sort of trouble gets a nice man shot in the middle of a night like this, so he can’t see a doctor onshore? Argument at the casino? Is the other man perhaps dead?”

“No, it was not an argument in the casino.”

He tilted the bottle back to his lips. I thought, I must keep him talking. He has to keep talking, to stay conscious. “And the other man?”

“Hmm. Do you really wish to know this, Mademoiselle?”

“Oh, priceless. I’m harboring a criminal fugitive.”

“Do not worry about that. You will be handsomely rewarded.”

“I don’t want to be rewarded. I want you to live.”

He didn’t reply, and I glanced back to make sure he hadn’t fainted. I wouldn’t have blamed him, lighter as he was of a pint or two of good red blood. But his eyes were open, each one containing a slim gold reflection of the lantern, and they were trained on me with an expression of profound … something.

I was about to ask him another question, but he spoke first.

“Where did you learn to treat a wound from a gun, Mademoiselle de Créouville?”

“I’ve never even seen a wound from a gun. But the sisters ran a charity hospital, and the men from the village got in regular brawls. Sometimes with knives.”

“The sisters? You are a nun?”

“No. I was at a convent school. I’ve only just escaped. Anyway, they made us all work in the charity hospital, because of Christ tending the feet of the poor. Hold on!” We hit a series of brisk chops, the wake of some unseen vessel plowing through the night sea nearby. Stefan grunted, and when the water calmed and I could relax my attention to the wheel, I glanced back again to see that his face was quite pale.

He spoke, however, without inflection. “You have a knack for it, I think. You did not scream at the blood, as most girls would. As I think most men might.”

“I have a brother. I’ve seen blood before.”

“Ah, the dashing mademoiselle. You tend wounds. You drive a boat fearlessly through the dark. What sort of sister is this for my friend Créouville? He said nothing about you before.”

“He has successfully ignored me for the past half decade, since we were sent back to France after our mother died.”

“I am sorry to hear about this.”

I tightened my hands on the wheel and stared ahead. The pinpricks were growing larger now, more recognizably human. I hardly ever ventured into Cannes, and certainly not by myself, but I’d passed the harbor enough to know its geography. “Where is your ship moored?” I asked.

He muttered something, and I looked back over my shoulder. His eyes were half closed, his back slumped.

“Stefan!” I said sharply.

He made a rolling motion and braced his hand on the side of the launch. His head snapped up. “So sorry. You were saying?”

I couldn’t leave the wheel; I couldn’t check his pulse, his skin, the state of his wound. A sliver of panic penetrated my chest: the unreality of this moment, of the warm salt wind on my face, of the starlight and the man bleeding in the stern of my father’s old wooden launch. Half an hour ago, I had been lying on a garden wall. “Stefan, you’ve got to concentrate,” I said, but I really meant myself. Annabelle, you’ve got to concentrate. “Stefan. Listen to me. You’ve got to stay awake.”

His gaze came to a stop on mine. “Yes. Right you are.”

“How are you feeling?”

“I am bloody miserable, Mademoiselle. My leg hurts like the devil and my head is a little sick. But at least I am bloody miserable with you.”

I faced the water again and turned up the throttle. “Very good. You’re flirting again, that’s a good sign. Now, tell me. Where is your ship moored? This side of the harbor, or the other?”

“Not the harbor. The Île Sainte-Marguerite. The Plateau du Milieu, on the south side, between the islands.”

I looked to the left, where a few lights clustered atop the thin line between black water and blacker sky. There wasn’t much on Sainte-Marguerite, only forest and the old Fort Royal. But a ship moored in the protected channel between Sainte-Marguerite and the Île Saint-Honorat—and many did moor there; it was a popular spot in the summer—would not be visible from the mainland.

“Hold on,” I said, and I began a sweeping turn to the left, to round the eastern point of the island. The launch angled obediently, and Stefan caught himself on the edge. The lantern slid across the deck. He stuck out his foot to stop its progress just as the boat hit a chop and heeled. Stefan swore.

“All right?” I said.

“Yes, damn it.”

I could tell from the bite in his words—or rather the lack of bite, the dissonance of the words themselves from the tone in which he said them—that he was slipping again, that he was fighting the black curtain. We had to reach this ship of his, the faster the better, and yet the faster we went the harder we hit the current. And I could not see properly. I was guided only by the pinprick lights and my own instinct for this stretch of coast.

“Just hurry,” said Stefan, blurry now, and I curled around the point and straightened out, so that the Plateau de Milieu lay before me, studded with perhaps a dozen boats tugging softly at their moorings. I glanced back at Stefan to see how he had weathered the turn.

“The western end,” he told me, gripping the side of the boat hard with his left hand while his right held the wadded-up white shirt against his wound. Someone had sacrificed his dinner jacket over Stefan’s shoulders, to protect that bare and bloody chest from the salt draft and the possibility of shock, and I thought I saw a few dark specks on the sleek white wool. But that was always the problem about blood. It traveled easily, like a germ, infecting its surroundings with messy promiscuity. I turned to face the sleeping vessels ahead, an impossible obstacle course of boats and mooring lines, and I thought, We have got to get that tourniquet off soon, or they will have to remove the leg.

But at least I could see a little better now, in the glow of the boat lights, and I pushed the throttle higher. The old engine opened its throat and roared. A curse floated out across the water behind us, as I zigzagged delicately around the mooring lines.

“I see you are an expert,” said Stefan. “This is reassuring.”

“Which one is yours?”

“You can’t see it yet. Just a moment.” We rounded another boat, a pretty sloop of perhaps fifty feet, and the rest of the passage opened out before us, nearly empty. Stefan said, with effort: “To the right, the last one.”

“What, the great big one?” I pointed.

“Yes, Mademoiselle. The great big one.”

I opened the throttle as far as it could go. We skipped across the water like a smooth, round stone, like when Charles and I were children and left to ourselves, and we would take the boat as fast as it could go and scream with joy in the briny wind, because when you were a child you didn’t know that boats sometimes crashed and people sometimes drowned. That vital young men were shot and sometimes bled to death.

Stefan’s yacht rose up rapidly before us, lit by a series of lights along the bow and the glow of a few portholes. It was long and elegant, a sweet beauty of a ship. The sides were painted black as far as the final row of portholes, where the white took over, like a wide neat collar around the rim, like a nun’s wimple. I saw the name Isolde painted on the bow. “Ahoy!” I called out, when we were fifty feet away. “Isolde ahoy!”

“They are likely asleep,” said Stefan.

I pulled back the throttle and brought the boat around. We bobbed on the water, sawing in our own wake, while I rummaged in the compartment under the wheel and brought out a small revolver.

“God in heaven,” said Stefan.

“I hope it’s loaded,” I said, and I pointed the barrel out to sea and fired.

The sound echoed off the water and the metal side of the boat. A light flashed on in one of the portholes, and a voice called out something outraged in German.

I cupped my hands around my mouth. “Isolde ahoy!”

“Ja, ja!”

“I have your owner! I have—oh, damn.”

The boat pitched. I grabbed the wheel. Behind me, Stefan was moving, and I hissed at him to sit down, he was going to kill himself.

But he ignored me and waved the bloodstained white shirt above his head. He brought the other hand to his mouth and yelled out a few choice German words, words I didn’t understand but comprehended perfectly, and then he crashed back down in his seat as if the final drops of life had been wrung out of him.

“Stefan!” I exclaimed. The boat was driving against the side of the ship; I steered frantically and let out the throttle a notch.

A figure appeared at the railing above, and an instant later a rope ladder unfurled down the curving side of the ship. I glanced at the slumping Stefan, whose eyes were closed, whose knee rested in a puddle of dark blood, and then back at the impossible swinging ladder, and I yelled frantically upward that someone had better get down here on the fucking double, because Stefan was about to die.

PEPPER (#u66efca19-d4d7-5046-b814-8c876e62a298)

Route A1A • 1966

1.

Mrs. Dommerich leans back on her palms and stares at the moon. “Isn’t it funny? The same old moon that stood above the sky when I was your age. It hasn’t changed a bit.”

“I don’t do moons,” says Pepper. “Who was this American of yours? The one having the party?”

“He was a friend. He was living in Paris at the time. A very good friend.”

“What kind of friend?”

Mrs. Dommerich laughs. “Not that kind, I assure you. He might have been, if I hadn’t already fallen in love with a friend of his.” Without warning, she slides off the hood of the car to stand in the sand, staring out into the ocean. “We should be going.”

“Going where?”

She doesn’t answer. Unlike Pepper, she didn’t follow her own advice and wear a cardigan, and her forearms are bare to the November night. She crosses them against her chest, just beneath her breasts. The material falls gently from her body, and Pepper decides she isn’t quite like Audrey Hepburn after all. She’s slender, but she isn’t skinny. There is a soft roundness to her, an inviting fullness about her breasts and hips and bottom, which she carries so gracefully on her light frame that you almost don’t notice, unless you’re looking for it. Unless you’re a man.