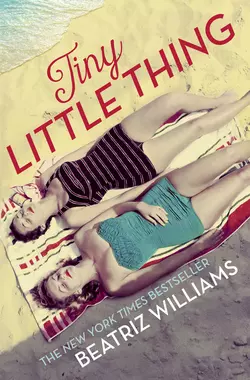

Tiny Little Thing: Secrets, scandal and forbidden love

Beatriz Williams

Secrets, scandal and indiscretions from the New York Times bestseller, Beatriz WilliamsCape Cod, 1966Christina Hardcastle – ‘Tiny’ to her illustrious family – is spending what should be an idyllic vacation at her husband Frank’s family estate. Despite her lush surroundings and the breathtaking future that now lies within reach, Tiny is beginning to feel more like a prisoner than a guest.As the season gets underway, three unwelcome visitors crack the façade of Tiny’s flawless life: her volatile sister Pepper; an envelope containing an incriminating photograph; and the intimidating figure of Frank’s cousin, Vietnam-war hero Caspian, who knows more about Tiny’s past than anyone else.As she struggles to break free from the gilded cage which entraps her, secrets from Tiny’s past are bubbling to the surface and threaten to unravel everything…

Copyright (#u28a9f67c-8d5b-5445-8fe5-3a45f2c41a11)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by Penguin Group USA 2016

First published in the UK by Harper 2016

Copyright © Beatriz Williams

Cover design by Alexandra Allden © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © H. Armstrong Roberts/Getty Images (front); Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (all other images).

Beatriz Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008134938

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008134945

Version: 2016-10-27

Dedication (#u28a9f67c-8d5b-5445-8fe5-3a45f2c41a11)

To all those who return from war not quite whole and to the people who love them

Contents

Cover (#u08873227-f539-5987-b285-a4434510f1fb)

Title Page (#u77c7db55-e578-510d-9ac2-fb2ccbeaf858)

Copyright

Dedication

Tiny, 1966: Cape Cod, Massachusetts (#u3b4fffc1-e797-5aa9-b5ad-fa8a6df1224a)

Caspian, 1964: Boston (#u7fbd3c36-0aa2-5c37-9f34-5403f94ed14d)

Tiny, 1966 (#u8f43c886-8f85-5b30-ade3-33acd4e12e90)

Caspian, 1964 (#u92642f8f-64f9-5354-af20-9abc2b803724)

Tiny, 1966 (#uf949cf70-d567-53ce-8669-b69f523e7bda)

Caspian, 1964 (#u804e56ef-04ed-52a2-840e-22a5b73bfc6e)

Tiny, 1966 (#u64375152-b666-510c-bb67-fbe6f19d5cc1)

Caspian, 1964 (#u0fd03c4c-5a6c-5684-b79c-f5c7bc6bf748)

Tiny, 1966 (#uc2da401b-3a55-5aeb-bf62-9e99899749db)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caspian, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs. Vivian Schuyler, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tiny, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Pepper, 1966 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Beatriz Williams

About the Publisher

Tiny, 1966 (#ulink_90889aaa-33be-51dc-9344-e595bfa07984)

CAPE COD, MASSACHUSETTS (#ulink_90889aaa-33be-51dc-9344-e595bfa07984)

The first photograph arrives in the mail on the same day that my husband appears on television at the Medal of Honor ceremony. It’s accompanied by the customary note written in block capital letters. By now, I know enough about politics—and about my husband’s family, I suppose—to suspect this isn’t a coincidence.

There’s no return address (of course, there wouldn’t be, would there?), but the envelope was postmarked yesterday in Boston, and the stamps are George Washington, five cents each. A plain manila envelope, letter size, of the sort they use in offices: I flip it back and forth between my fingers, while my heart bounds and rebounds against my ribs.

“Tiny, my dear.” It’s my husband’s grandmother, calling from the living room. “Aren’t you going to watch the ceremony?”

She has a remarkable way of forming a sociable question into a court summons, and like a court summons, she can’t be ignored. I smooth my hand against the envelope once, twice, as if I can evaporate the contents—poof, presto!—in the stroke of a palm, and I slide it into one of the more obscure pigeonholes in the secretary, where the mail is laid every day by the housekeeper.

“Yes, of course,” I call back.

The television has been bought new for the occasion. Generally, Granny Hardcastle frowns on modern devices; even my husband, Franklin, has to hide in the attic in order to listen to Red Sox games on the radio. The wireless, she calls it, a little disdainfully, though she’s not necessarily averse to Sinatra or Glenn Miller in the evenings, while she sits in her favorite chintz chair in the living room and drinks her small glass of cognac. It drowns out the sound of the ocean, she says, which I can never quite comprehend. In the first place, you can’t drown out the ocean when it flings itself persistently against your shore, wave after wave, only fifty yards past the shingled walls of your house, no matter how jazzy the trumpets backing up Mr. Sinatra.

In the second place, why would you want to?

I pause at the tray to pour myself a glass of lemonade. I add a splash of vodka, but only a tiny one. “Have they started yet?” I ask, trying to sound as cool as I look. The vodka, I’ve found, is a reliable refrigerant.

“No. They’re trying to sell me Clorox.” Granny Hardcastle stubs out her cigarette in the silver ashtray next to her chair—she smokes habitually, but only in front of women—and chews on her irony.

“Lemonade?”

“No, thank you. I’ll have another cigarette, though.”

I make my way to the sofa and open the drawer in the lamp table, where Mrs. Hardcastle keeps the cigarettes. Our little secret. I shake one out of the pack and tilt my body toward the television set, feigning interest in bleach, so that Franklin’s grandmother won’t see the wee shake of my fingers as I strike the lighter and hold it to the tip of the cigarette. These are the sorts of details she notices.

I hand her the lit cigarette.

“Sit down,” she says. “You’re as restless as a cat.”

There. Do you see what I mean? Just imagine spending the summer in the same house with her. You’d be slipping the vodka into your lemonade in no time, trust me.

The French doors crash open from the terrace.

“Has it started yet?” asks one of the cousins—Constance, probably—before they all clatter in, brown limbed, robed in pinks and greens, smelling of ocean and coconuts.

“Not yet. Lemonade?”

I pour out four or five glasses of lemonade while the women arrange themselves about the room. Most of them arrived as I did, at the beginning of summer, members of the annual exodus of women and children from the Boston suburbs; some of them have flown in from elsewhere for the occasion. The men, with a few exceptions, are at work—this is a Wednesday, after all—and will join us tomorrow for a celebratory dinner to welcome home the family hero.

I pour a last glass of lemonade for Frank’s four-year-old niece Nancy and settle myself into the last remaining slice of the sofa, ankles correctly crossed, skirt correctly smoothed. The cushions release an old and comforting scent. Between the lemonade and the ambient nicotine and the smell of the sofa, I find myself able to relax the muscles of my neck, and maybe one or two in my back as well. The television screen flickers silently across the room. The bottle of bleach disappears, replaced by Walter Cronkite’s thick black eyeglass frames, and behind them, Mr. Cronkite himself, looking especially grave.

“Tiny, dear, would you mind turning on the sound?”

I rise obediently and cut a diagonal track across the rug to the television. It’s not a large set, nor one of those grandly appointed ones you see in certain quarters. Like most of our caste, Mrs. Hardcastle invests lavishly in certain things, things that matter, things that last—jewelry, shoes, houses, furniture, the education of the next generation of Hardcastles—and not in others. Like television sets. And food. If you care to fasten your attention to the tray left out by the housekeeper, you’ll spy an arrangement of Ritz crackers and pimiento spread, cubes of American cheese and small pale rubbery weenies from a jar. As I pass them by, on my return journey, I think of my honeymoon in the south of France, and I want to weep.

“You should eat,” Constance says, when I sit back down next to her. Constance is as fresh and rawboned as a young horse, and believes that every thin woman must necessarily be starving herself.

“I’m not hungry yet. Anyway, I had a large breakfast.”

“Shh. Here they are,” says Granny. Her armchair is right next to my place at the end of the sofa. So close I can smell her antique floral perfume and, beneath it, the scent of her powder, absorbing the joy from the air.

The picture’s changed to the Rose Garden of the White House, where the president’s face fills the screen like a grumpy newborn.

“It looks hot,” says Constance. A chorus of agreement follows her. People generally regard Constance’s opinions as addenda to the Ten Commandments around here. The queen bee, you might say, and in this family that’s saying a lot. Atop her lap, a baby squirms inside a pink sundress, six months old and eager to try out the floor. “Poor Frank, having to stand there like that,” she adds, when it looks as if President Johnson means to prolong the anticipation for some time, droning on about the importance of the American presence in Vietnam and the perfidy of the Communists, while the Rose Garden blooms behind him.

A shadow drifts in from the terrace: Constance’s husband, Tom, wearing his swim trunks, a white T-shirt, and an experimental new beard of three or four days’ growth. He leans his salty wet head against the open French door and observes us all, women and children and television. I scribble a note on the back of my brain, amid all the orderly lists of tasks, organized by category, to make sure the glass gets cleaned before bedtime.

Granny leans forward. “You should have gone with him, Tiny. It looks much better when the wife’s by his side. Especially a young and pretty wife like you. The cameras love a pretty wife. So do the reporters. You’re made for television.”

She speaks in her carrying old-lady voice, into a pool of studied silence, as everyone pretends not to have heard her. Except the children, of course, who carry on as usual. Kitty wanders up to my crossed legs and strokes one knee. “I think you’re pretty, too, Aunt Christina.”

“Well, thank you, honey.”

“Careful with your lemonade, kitten,” says Constance.

I caress Kitty’s soft hair and speak to Granny quietly. “The doctor advised me not to, Mrs. Hardcastle.”

“My dear, it’s been a week. I went to my niece’s christening the next day after my miscarriage.”

The word miscarriage pings around the room, bouncing off the heads of Frank’s florid female cousins, off Kitty’s glass of sloshing lemonade, off the round potbellies of the three or four toddlers wandering around the room, off the fat sausage toes of the two plump babies squirming on their mothers’ laps. Every one of them alive and healthy and lousy with siblings.

After a decent interval, and a long drag on her cigarette, Granny Hardcastle adds: “Don’t worry, dear. It’ll take the next time, I’m sure.”

I straighten the hem of my dress. “I think the president’s almost finished.”

“For which the nation is eternally grateful,” says Constance.

The camera now widens to include the entire stage, the figures arrayed around the president, lit by a brilliant June sun. Constance is right; you can’t ignore the heat, even on a grainy black-and-white television screen. The sweat shines from the white surfaces of their foreheads. I close my eyes and breathe in the wisps of smoke from Constance’s nearby cigarette, and when I open them again to the television screen, I search out the familiar shape of my husband’s face, attentive to his president, attentive to the gravity of the ceremony.

A horse’s ass, Frank’s always called Johnson in the privacy of our living room, but not one member of the coast-to-coast television audience would guess this opinion to look at my husband now. He’s a handsome man, Franklin Hardcastle, and even more handsome in person, when the full Technicolor impact of his blue eyes hits you in the chest and that sleek wave of hair at his forehead commands the light from three dimensions. His elbows are crooked in perfect right angles. His hands clasp each other respectfully behind his back.

I think of the black-and-white photograph in its envelope, tucked away in the pigeonhole of the secretary. I think of the note that accompanied it, and my hand loses its grip, nearly releasing the lemonade onto the living room rug.

The horse’s ass has now adjusted his glasses and reads from the citation on the podium before him. He pronounces the foreign geography in his smooth Texas drawl, without the slightest hesitation, as if he’s spent the morning rehearsing with a Vietnamese dictionary.

“… After carrying his wounded comrade to safety, under constant enemy fire, he then returned to operate the machine gun himself, providing cover for his men until the position at Plei Me was fully evacuated, without regard to the severity of his wounds.”

Oh, yes. That. The severity of his wounds. I’ve heard the phrase before, as the citation was read before us all in Granny Hardcastle’s dining room in Brookline, cabled word for word at considerable expense from the capital of a grateful nation. I can also recite from memory an itemized list of the wounds in question, from the moment they were first reported to me, two days after they’d been inflicted. They are scored, after all, on my brain.

None of that helps a bit, however. My limbs ache, actually hurt as I hear the words from President Johnson’s lips. My ears ring, as if my faculties, in self-defense, are trying to protect me from hearing the litany once more. How is it possible I can feel someone else’s pain like that? Right bang in the middle of my bones, where no amount of aspirin, no quantity of vodka, no draft of mentholated nicotine can touch it.

My husband listens to this recital without flinching. I focus on his image in that phalanx of dark suits and white foreheads. I admire his profile, his brave jaw. The patriotic crease at the corner of his eye.

“He does look well, doesn’t he?” says Granny. “Really, you’d never know about the leg. Could you pass me the cigarettes?”

One of the women reaches for the drawer and passes the cigarettes silently down the row of us on the sofa. I hand the pack and lighter to Granny Hardcastle without looking. The camera switches back to a close-up of the president’s face, the conclusion of the commendation.

You have to keep looking, I tell myself. You have to watch.

I close my eyes again. Which is worse somehow, because when your eyes are closed, you hear the sounds around you even more clearly than before. You hear them in the middle of your brain, as if they originated inside you.

“This nation presents to you, Major Caspian Harrison, its highest honor and its grateful thanks for your bravery, your sacrifice, and your unflinching care for the welfare of your men and your country. At a time when heroes have become painfully scarce, your example inspires us all.”

From across the room, Constance’s husband makes a disgusted noise. The hinges squeak, and a gust of hot afternoon air catches my cheek as the door to the terrace widens and closes.

“Why are you shutting your eyes, Tiny? Are you all right?”

“Just a little dizzy, that’s all.”

“Well, come on. Get over it. You’re going to miss him. The big moment.”

I open my eyes, because I have to, and there stands President Lyndon Johnson, shaking hands with the award’s recipient.

The award’s recipient: my husband’s cousin, Major Caspian Harrison of the Third Infantry Division of the U.S. Army, who now wears the Medal of Honor on his broad chest.

His face, unsmiling, which I haven’t seen in two years, pops from the screen in such familiarity that I can’t swallow, can hardly even breathe. I reach forward to place my lemonade on the sofa table, but in doing so I can’t quite strip my gaze from the sandy-gray image of Caspian on the television screen and nearly miss my target.

Next to him, tall and monochrome, looking remarkably presidential, my husband beams proudly.

He calls me a few hours later from a hotel room in Boston. “Did you see it?” he asks eagerly.

“Of course I did. You looked terrific.”

“Beautiful day. Cap handled himself fine, thank God.”

“How’s his leg?”

“Honey, the first thing you have to know about my cousin Cap, he doesn’t complain.” Frank laughs. “No, he was all right. Hardly even limped. Modern medicine, it’s amazing. I was proud of him.”

“I could see that.”

“He’s right here, if you want to congratulate him.”

“No! No, please. I’m sure he’s exhausted. Just tell him … tell him congratulations. And we’re all very proud, of course.”

“Cap!” His voice lengthens. “Tiny says congratulations, and they’re all proud. They watched it from the Big House, I guess. Did Granny get that television after all?” This comes through more clearly, directed at me.

“Yes, she did. Connie’s husband helped her pick it out.”

“Well, good. At least we have a television in the house now. We owe you one, Cap buddy.”

A few muffled words find the receiver. Cap’s voice.

Frank laughs again. “You can bet on it. Besides the fact that you’ve given my poll numbers a nice little boost today, flashing that ugly mug across the country like that.”

Muffle muffle. I try not to strain my ears. What’s the point?

Whatever Caspian said, my husband finds it hilarious. “You little bastard,” he says, laughing, and then (still laughing): “Sorry, darling. Just a little man-to-man going on here. Say, you’ll never guess who’s driving down with us tomorrow morning.”

“I can’t imagine.”

“Your sister Pepper.”

“Pepper?”

“Yep. She hopped a ride with us from Washington. Staying with a friend tonight.”

“Well, that’s strange,” I say.

“What, staying with a friend? I’d say par for the course.” Again, the laughter. So much laughing. What a good mood he’s in. The adrenaline rush of public success.

“No, I mean coming for a visit like this. Without even saying anything. She’s never been up here before.” Which is simply a tactful way of saying that Pepper and I have never gotten along, that we’ve only cordially tolerated each other since we were old enough to realize that she runs on jet fuel, while I run on premium gasoline, and the two—jets and Cadillacs—can’t operate side by side without someone’s undercarriage taking a beating.

“My fault, I guess. I saw her at the reception afterward, looking a little blue, and I asked her up. In my defense, I never thought she’d say yes.”

“Doesn’t she have to work?”

“I told her boss she needed a few days off.” Frank’s voice goes all smart and pleased with itself. Pepper’s boss, it so happens, is the brand-new junior senator from the great state of New York, and a Hardcastle’s always happy to get the better of a political rival.

“Well, that’s that, then. I’ll see that we have another bedroom ready. Did she say how long she was planning to stay?”

“No,” says Frank. “No, she didn’t.”

I wait until ten o’clock—safe in my bedroom, a fresh vase of hyacinths quietly perfuming the air, the ocean rushing and hushing outside my window—before I return my attention to the photograph in the manila envelope.

I turn the lock first. When Frank’s away, which is often, his grandmother has an unsavory habit of popping in for chats on her way to bed, sometimes knocking first and sometimes not. My dear, she begins, in her wavering voice, each r lovingly rendered as an h, and then comes the lecture, delivered with elliptical skill, in leading Socratic questions of which a trial lawyer might be proud, designed to carve me into an even more perfect rendering, a creature even more suited to stand by Franklin Hardcastle’s side as he announced his candidacy for this office and then that office, higher and higher, until the pinnacle’s reached sometime before menopause robs me of my photogenic appeal and my ability to charm foreign leaders with my expert command of both French and Spanish, my impeccable taste in clothing and manners, my hard-earned physical grace.

In childhood, I longed for the kind of mother who took an active maternal interest in her children. Who approached parenthood as a kind of master artisan, transforming base clay into porcelain with her own strong hands, instead of delegating such raw daily work to a well-trained and poorly paid payroll of nannies, drivers, and cooks. Who rose early to make breakfast and inspect our dress and homework every morning, instead of requiring me to deliver her a tall glass of her special recipe, a cup of hot black coffee, and a pair of aspirin at eight thirty in order to induce a desultory kiss good-bye.

Now I know that affluent neglect has its advantages. I’ve learned that striving for the telescopic star of your mother’s attention and approval is a lot easier than wriggling under the microscope of—well, let’s just pick an example, shall we?—Granny Hardcastle.

But I digress.

I turn the lock and kick off my slippers—slippers are worn around the house, when the men aren’t around, so as not to damage the rugs and floorboards—and pour myself a drink from Frank’s tray. The envelope now lies in my underwear drawer, buried in silk and cotton, where I tucked it before dinner. I sip my Scotch—you know something, I really hate Scotch—and stare at the knob, until the glass is nearly empty and my tongue is pleasantly numb.

I set down the glass and retrieve the envelope.

The note first.

I don’t recognize the writing, but that’s the point of block capital letters, isn’t it? The ink is dark blue, the letters straight and precise, the paper thin and unlined. Typing paper, the kind used for ordinary business correspondence, still crisp as I finger the edges and hold it to my nose for some sort of telltale scent.

DOES YOUR HUSBAND KNOW?

WHAT WOULD THE PAPERS SAY?

STAY TUNED FOR A MESSAGE FROM YOUR SPONSOR.

P.S. A CONTRIBUTION OF $1,000 IN UNMARKED BILLS WOULD BE APPRECIATED.

J. SMITH

PO BOX 55255

BOSTON, MA

Suitably dramatic, isn’t it? I’ve never been blackmailed before, but I imagine this is how the thing is done. Mr. Smith—I feel certain this soi-disant “J” is a man, for some reason; there’s a masculine quality to the whole business, to the sharp angles of the capital letters—has a damning photograph he wants to turn into cash. He might have sent the photograph to Frank, of course, but a woman is always a softer target. More fearful, more willing to pay off the blackmailer, to work out some sort of diplomatic agreement, a compromise, instead of declaring war. Or so a male perpetrator would surmise. A calculated guess, made on the basis of my status, my public persona: the pretty young wife of the candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts, whose adoring face already gazes up at her husband from a hundred campaign photographs.

Not the sort of woman who would willingly risk a photograph like this appearing on the front page of the Boston Globe, in the summer before my husband’s all-important first congressional election.

Is he right?

The question returns me, irresistibly and unwillingly, to the photograph itself.

I rise from the bed and pour myself another finger or so of Frank’s Scotch. There’s no vodka on the tray, under the fiction that Frank’s wife never drinks in bed. I roll the liquid about in the glass and sniff. That’s my problem with Scotch, really: it always smells so much better than it tastes. Spicy and mysterious and potent. The same way I regarded coffee, when I was a child, until I grew up and learned to love the taste even more than the scent.

So maybe, if I drink enough, if I pour myself a glass or two of Frank’s aged single malt every night to wash away the aftertaste of Granny Hardcastle’s lectures, I’ll learn to love the flavor of whiskey, too.

I set the glass back on the tray, undrunk, and return to the bed, where I stretch myself out crosswise, my stomach cushioned by the lofty down comforter, my bare toes dangling from the edge. I pull the photograph from the envelope, and I see myself.

Me. The Tiny of two years ago, a Tiny who had existed for the briefest of lifetimes: not quite married, slender and cream-skinned, bird-boned and elastic, silhouetted against a dark sofa of which I can still remember every thread.

About to make the most disastrous mistake of her life.

Caspian, 1964 (#ulink_3b69acdf-f240-5726-8b2e-089cc58afc84)

BOSTON (#ulink_3b69acdf-f240-5726-8b2e-089cc58afc84)

Eleven o’clock came and went on the tea-stained clock above the coffee shop door, and still no sign of Jane.

Not that he was waiting. Not that her name was Jane.

Or maybe it was. Why the hell not? Jane was a common name, a tidy feminine name; the kind of girl you could take home to your mother, if you had one. Wouldn’t that be a gas, if he sat down at Jane Doe’s booth one day and asked her name, and she looked back at him over the rim of her coffee cup, just gazed at him with those wet chocolate eyes, and said I’m Jane, like that.

Yeah. Just like that.

Not that he’d ever sit down at her booth. When, every day at ten o’clock sharp, Jane Doe settled herself in her accustomed place at Boylan’s Coffee Shop and ordered a cup of finest Colombian with cream and sugar and an apricot Danish, she enacted an invisible electric barrier about herself, crossable only by waitresses bearing pots of fresh coffee and old Boylan himself, gray-haired and idolatrous. Look but don’t touch. Admire but don’t flirt. No virile, young red-blooded males need apply, thank you terribly, and would you please keep your dirty, loathsome big hands to yourself.

“More coffee, Cap?”

He looked down at the thick white cup in the thick white saucer. His loathsome big hand was clenched around the bowl. The remains of his coffee, fourth refill, lay black and still at the bottom. Out of steam. He released the cup and reached for his back pocket. “No thanks, Em. I’d better be going.”

“Suit yourself.”

He dropped a pair of dollar bills on the Formica—a buck fifty for the bacon and eggs, plus fifty cents for Em, who had two kids and a drunk husband she complained about behind the counter to the other girls—and stuffed his paperback in an outside pocket of his camera bag. The place was quiet, hollow, denuded of the last straggling breakfasters, holding its breath for the lunch rush. He levered himself out of the booth and hoisted his camera bag over his shoulder. His shoes echoed on the empty linoleum.

Em’s voice carried out behind him. “I bet she’s back tomorrow, Cap. She just lives around the corner.”

“I don’t know what the hell you’re talking about, Em.” He hurled the door open in a jingle-jangle of damned bells that jumped atop his nerves.

“Wasn’t born yesterday,” she called back.

Outside, the Back Bay reeked of its old summer self—car exhaust and effluvia and sun-roasted stone. An early heat wave, the radio had warned this morning, and already you could feel it in the air, a familiar jungle weight curling down the darling buds of May. To the harbor, then. A long walk by civilian standards, but compared to a ten-mile hike in a shitty tropical swamp along the Laos border, hauling fifty pounds of pack and an M16 rifle, sweat rolling from your helmet into your stinging eyes, fucking Vietcong ambush behind every tree, hell, Boston Harbor’s a Sunday stroll through the gates of paradise.

Just a little less exciting, that was all, but he could live without excitement for a while. Everyone else did.

Already his back was percolating perspiration, like the conditioned animal he was. The more vigorous the athlete, the more efficient the sweat response: you could look it up somewhere. He lifted his automatic hand to adjust his helmet, but he found only hair, thick and a little too long.

He turned left and struck down Commonwealth Avenue, around the corner, and holy God there she was, Jane Doe herself, hurrying toward him in an invisible cloud of her own petite ladylike atmosphere, checking her watch, the ends of her yellow-patterned silk head scarf fluttering in her draft.

He stopped in shock, and she ran bang into him. He caught her by the small pointy elbows.

“Oh! Excuse me.”

“My fault.”

She looked up and up until she found his face. “Oh!”

He smiled. He couldn’t help it. How could you not smile back at Miss Doe’s astounded brown eyes, at her pink lips pursed with an unspoken Haven’t we met before?

“From the coffee shop,” he said. His hands still cupped her pointy elbows. She was wearing a crisp white shirt, a pair of navy pedal pushers, a dangling trio of charms in the hollow of her throat on a length of fine gold chain. As firm and dainty as a young deer. He could lift her right up into the sky.

“I know that.” She smiled politely. The ends of her yellow head scarf rested like sunshine against her neck. “Can I have my elbows back?”

“Must I?”

“You really must.”

Her pocketbook had slipped down her arm. She lifted her left hand away from his clasp and hoisted the strap back up to her right shoulder, and as she did so, the precocious white sun caught the diamond on her ring finger, like a mine exploding beneath his unsuspecting foot.

But hell. Wasn’t that how disasters always struck? You never saw them coming.

Tiny, 1966 (#ulink_50109e48-6aec-5f9a-8dda-e0b5425cd10d)

When I come in from the beach the next morning, Frank’s father is seated at the end of the breakfast table, eating pancakes.

“Oh! Good morning, Mr. Hardcastle.” I slide into my chair. The French doors stand open behind me, and the salt breeze, already warm, spreads pleasantly across my shoulders.

My father-in-law smiles over his newspaper. “Good morning, Tiny. Out for your walk already?”

“Oh, you know me. Anyway, Percy wakes me up early. Wants his walkies.” I pat the dog’s head, and he sinks down at the foot of my chair with a fragrant sigh. “You must have come in last night.”

“Yes, went into the campaign office for a bit, and then drove down, long past bedtime. I hope I didn’t wake anyone.”

“Not at all.” There’s no sign of the housekeeper, so I reach for the coffeepot myself. “How was the trip? We were watching on television from the living room.”

“Excellent, excellent. You should have been there.”

“The doctors advised against it.”

Mr. Hardcastle’s face lengthens. “Of course. I didn’t actually mean that you should have been there, of course. Air travel being what it is.” He reaches across the white tablecloth and pats my hand, the same way I’ve just patted Percy. “How are you feeling?”

“Much better, thank you. Are you staying long?”

“Just for the dinner tonight, then I have to get back in Boston. Campaign’s heating up.” He winks.

“I’m sure Frank appreciates all your help.”

“He has a right to my help, Tiny. That’s what family is for. We’re all in this together, aren’t we? That’s what makes us so strong.” He sets down his newspaper, folds it precisely, and grasps his coffee cup. “I understand they had plans last night. Frank and Cap and your sister.”

“Did they?”

“Oh, they were in high spirits on the plane from Washington. Nearly brought the old bird down a couple of times. I wouldn’t expect them here until afternoon at least.”

“Well, they should go out. I’m sure Major Harrison deserves a little fun, after all he’s been through. I hope Frank took him somewhere lively. I hope they had a ball.”

“And it doesn’t bother you? All that fun without you?”

“Oh, boys will be boys, my mother always said. Always better to let them get it out of their systems.”

The swinging door opens from the kitchen, and Mrs. Crane backs through, bearing a plate of breakfast in one hand and a pot of fresh coffee in the other. The toast rack is balanced on a spare thumb. “Here you are, Mrs. Hardcastle,” she says.

“Thank you so much, Mrs. Crane.”

As I pick up my knife and fork, my skin prickles under the weight of someone’s observation. I turn my head, right smack into the watchful stare of my father-in-law. His eyes have narrowed, and his mouth turns up at one corner, causing a wave of wrinkles to ripple into his cheekbone.

“What is it?” I ask.

The smile widens into something charming, something very like his son’s best campaign smile. The smile Frank wore when he asked me to marry him.

“Nothing in particular,” he says. “Just that you’re really the perfect wife. Frank’s lucky to have you.” He reaches for his newspaper and flicks it back open. “We’re just lucky to have you in the family.”

Frank’s yellow convertible pulls up with a toothsome roar and a spray of miniature gravel at one o’clock in the afternoon, just as we’ve finished a casual lunch in the screened porch propped up above the ocean.

I’ve promised myself not to drink nor smoke before his arrival, whatever the provocation, and I managed to keep that promise all morning long, so my husband finds me fresh and serene and smelling of lemonade. “Hello there!” I sing out, approaching the car in my pink Lilly shift with the dancing monkeys, flat heels grinding crisply against the gravel. I rise up on my toes to kiss him.

“Well, hello there!” He’s just as cheerful as the day before, though there’s clearly occurred a night in between, which has taken due toll on his skin tone and the brightness of his Technicolor eyeballs. “Say hello to your sister.”

“Be gentle.” Pepper climbs out of the passenger seat, all glossy limbs and snug tangerine dress, and eases her sunglasses tenderly from her eyes. “Pepper’s hung, darling.”

Do you know, I’ve never quite loved my sister the way I do in that instant, as she untangles herself from Frank’s convertible to join me in my nest of in-laws. A memory assaults me—maybe it’s the tangerine dress, maybe it’s the familiar grace of her movements—of a rare evening out with Pepper and Vivian a few years ago, celebrating someone’s graduation, in which I’d drunk too much champagne and found myself cornered in a seedy nightclub hallway by some intimidating male friend of Pepper’s, unable to politely excuse myself, until Pepper had found us and nearly ripped off the man’s ear with the force of her ire. You can stick your pretty little dick into whatever poor drunk schoolgirl you like—or words equally elegant—but you stay the hell away from my sister, capiche?

And he slunk away. Capiche, all right.

Pepper. Never to be trusted with boyfriends and husbands, mind you, but a Valkyrie of family loyalty against outsider attack.

I step forward, arms open, and embrace her with an enthusiasm that astonishes us both. What’s more, she hugs me back just as hard. I kiss her cheek and draw away, still holding her by the shoulders, and say something I’d never said before, on an instinct God only knows: “Are you all right, Pepper?”

She’s just so beautiful, Pepper, even and perhaps especially windblown from a two-hour drive along the highway in Frank’s convertible. Disheveled suits her, the way it could never suit me. Her eyes return the sky. A little too bright, I find myself thinking. “Perfectly all right, sister dear,” she says, “except I couldn’t face breakfast, and by the time we crossed the Sagamore Bridge I was famished enough to gobble up your cousin’s remaining leg. No matter how adorable he is.”

I must look horrified, because she laughs. “Not really. But a sandwich would do nicely. And a vodka tonic. Heavy on the vodka. Your husband drives like a maniac.”

“Make it two,” says Frank, from behind the open lid of the trunk, unloading suitcases.

“But where is Major Harrison?” I can’t bring myself to say Caspian, just like that. I feign looking about, as if I’d just recognized his absence from Frank’s car.

“Oh, we dropped him off already, next door. That’s a lovely place he’s got. Not as nice as yours.” She nods at the Big House. “But then, his needs are small, the poor little bachelor.”

“Well, that’s a shame. I was looking forward to meeting him at last.”

Frank ranges up with the suitcases. “That’s right. He missed the wedding, didn’t he?”

“Oh, I can promise he wasn’t there at your wedding.” Pepper laughs. “You think I’d forget a man like that, if he were present and accounted for?”

Even battling a hangover, Pepper’s the same old Pepper, flirting with my husband by way of making suggestive remarks about another man. I take her arm and steer her toward the house, leaving Frank to trail behind us with the suitcases. The act fills me with zing. “But he’s still coming for dinner, isn’t he?”

Franks speaks up. “He’d better. He’s the guest of honor.”

“If he hasn’t come over by six o’clock,” says Pepper, “I’d be happy to pop next door and help him dress.”

Guests first. I lead Pepper upstairs to her room and show her the bathroom, the wardrobe, the towels, the bath salts, the carafe of water in which the lemon slices bump lazily about the ice cubes. I’m about to demonstrate the arcane workings of the bath faucet when she pushes me toward the door. “Go on, go on. I can work a faucet, for God’s sake. Go say hello to your husband. Have yourselves some après-midi.” She winks. Obviously Mums hasn’t told her about the miscarriage. Or maybe she has, and Pepper doesn’t quite comprehend the full implications.

Anyway, the zing from the driveway starts dissolving right there, and by the time I reach my own bedroom, by the time my gaze travels irresistibly to the top drawer of my dresser, closed and polished, it’s vanished without trace.

Frank’s in the bathroom, faucet running. The door is cracked open, and a film of steam escapes to the ceiling. I turn to his suitcase, which lies open on the bed, and take out his shirts.

He’s an efficient packer, my husband, and most of the clothes have been worn. Hardly an extra scrap in the bunch. I toss the shirts and the underwear in the laundry basket, I fold the belt and silk ties over the rack in his wardrobe, I hang the suits back in their places along the orderly spectrum from black to pale gray.

I make a point of avoiding the pockets, because I refuse to become that sort of wife, but when I return to the suitcase a glint of metal catches my eye. Perhaps a cuff link, I think, and I stretch out my finger to fish it from between Frank’s dirty socks.

It’s not a cuff link. It’s a key.

A house key, to be more specific; or so I surmise, since you can’t start a car or open a post office box with a York. I finger the edge. There’s no label, nor is it attached to a ring of any kind. Like Athena, it seems to have emerged whole from Zeus’s head, if Zeus’s head were a York lock.

I walk across the soft blue carpet to the bathroom door and push it wide. Frank stands before the mirror, bare chested, stroking a silver razor over his chin. A few threads of shaving cream decorate his cheeks, which are flushed from the heat of the water and the bathroom itself.

“Is this your key, darling?” I hold it up between my thumb and forefinger.

Frank glances at my reflection. His eyes widen. He turns and snatches the key with his left hand, while his right holds the silver razor at the level of his face. “Where did you get that?”

“The bottom of the suitcase.”

He smiles. “It must have slipped off the ring somehow. It’s the key to the campaign office. I was working late the other day.”

“I can go downstairs and put it back on your ring.”

He sets the key down on the counter, next to his shaving soap, and turns his attention back to his sleek face. “That’s all right. I’ll put it back myself.”

“It’s no trouble.”

Frank lifts the razor back to his chin. “No need.”

By the time I’ve emptied the suitcase and tucked away the contents, careful and deliberate, Frank has finished shaving and walks from the bathroom, towel slung around his neck, still dabbing at his chin.

“Thanks.” He kisses me on the cheek. His skin is damp and sweet against mine. “Missed you, darling.”

“I missed you, too.”

“You look beautiful in that dress.” He continues to the wardrobe. “Do you think there’s time for a quick sail before dinner?”

“I don’t mind, if you can square that with your grandmother. Naturally she’s dying to hear every detail of your trip. Especially the juicy bits afterward.”

He makes a dismissive noise, for which I envy him. “Join me?”

“No, not with the dinner coming up, I’m afraid.” I wind the zipper around the edge of the empty suitcase. Frank tosses the towel on the bed and starts dressing. I pick up the towel and return it to the bathroom. Frank’s buttoning his shirt. I grasp the handle of the suitcase.

“No, no. I’ll get it.” He pushes my hand away and lifts the suitcase himself. It’s not heavy, but the gesture shows a certain typical gallantry, and I think how lucky I am to have the kind of husband who steps in to carry bulky objects. Who invariably offers me his jacket when the wind picks up. He stows the suitcase in the wardrobe, next to the shoes, while I stand next to the bed, breathing in the decadent scent of hyacinths out of season, and wonder what a wife would say right now.

“How was the drive?”

“Oh, it was all right. Not much traffic.”

“And your cousin? It didn’t bother him?”

Frank smiles at me. “His name is Cap, Tiny. You can say it. Or Caspian, if you insist on being your formal self.”

“Caspian.” I smooth my hands down my pink dress as I say the word.

“I know you’ve never met him, but he’s a nice guy. Really. He looks intimidating, sure, but he’s just big and quiet. Just an ordinary guy. Eats hamburgers, drinks beer.”

“Oh, just an ordinary beer-drinking guy who happens to have been awarded the Medal of Honor yesterday for valiant combat in Vietnam.” I force out a smile. “Do we know how many men he killed?”

“Probably a lot. But that’s just war, honey. He’s not going to jump from the table and set up a machine gun nest in the dining room.”

“Of course not. It’s just … well, like you said. Everybody else knows him so well, and this entire dinner is supposed to revolve around him. …”

“Hey, now. You’re not nervous, are you? Running a big family dinner like this?” Frank takes a step toward me. His hair, sleeked back from his forehead with a brush and a dab of Brylcreem, catches a bit of blond light from the window, the flash of the afternoon ocean.

“Don’t be silly.”

He puts his hands around my shoulders. “You’ll be picture-perfect, honey. You always are.” He smells of Brylcreem and soap. Of mint toothpaste covering the hint of stale cigarette on his breath. They were probably smoking on the long road from New York, he and Pepper, while Caspian, who doesn’t smoke, sat in the passenger seat and watched the road ahead. He kisses me on the lips. “How are you feeling? Back to normal?”

“I’m fine. Not quite back to normal, exactly. But fine.”

“I’m sorry I had to leave so soon.”

“Don’t worry. I wasn’t expecting the world to stop.”

“We’ll try again, as soon as you’re ready. Just another bump on the road.”

“If you tell me you’re just sure it will take this time,” I tell him, “I’ll slap you.”

He laughs. “Granny again?”

“Your impossibly fertile family. Do you know, there are at least four babies here this week, the last time I counted?”

Frank gathers me close. “I’m sorry. You’re such a trouper, Tiny.”

“It’s all right. I can’t blame other people for having babies, can I?”

He sighs, deep enough to lift me up and down on his chest. “Honey, I know this doesn’t make it any better. But I promise you we’ll have one of our own. We’ll just keep trying. Call in the best doctors, if we have to.”

His kindness undoes me. I lift my thumb to my eyes, so as not to spoil his shirt with any sodden traces of makeup. “Yes, of course.”

“Don’t cry, honey. We’ll do whatever it takes.”

“It’s just … I just …” Want it so badly. Want a baby of my own, a person of my own, an exchange of whole and uncomplicated love that belongs solely to me. If we have a baby, everything will be fine, because nothing else will matter.

“I know, darling. I know.”

He pats my back. Something wet touches my ankle, through my stocking, and I realize that Percy has jumped from the bed, and now attempts to comfort my foot. Frank’s body is startlingly warm beneath his shirt, warm enough to singe, and I realize how cold my own skin must be. I gather myself upward, but I don’t pull away. I don’t want Frank to see my face.

“All better?” He loosens his arms and shifts his weight back to his heels.

“Yes. All better.” But still I hold on, not quite ready to release his warmth. “So tell me about your cousin.”

“Cap.”

“Yes, Cap. He has a sister, doesn’t he?”

“Yes. But she’s staying in San Diego. Her girls aren’t out of school for the summer until next week.”

“And everything else is all right with him? He’s recovered from … all that?”

“Seems so. Same old Cap. A little quieter, maybe.”

“Anything I should know? You know, physical limitations?” I glance at my dresser drawer. “Money problems?”

Frank flinches. “Money problems? What makes you ask that?”

“Well, I don’t want to say anything awkward. And I know some of the cousins are better off than the others.”

He gives me a last pat and disengages me from his arms. “He’s fine, as far as I know. Both parents gone, so he’s got their money. Whatever that was. Anyway, he’s not a big spender.”

“How do you know?”

“I went out with him last night, remember? You can tell a lot about a man on a night out.”

Frank winks and heads back to the wardrobe, whistling a few notes. I look down at Percy’s anxious face, his tail sliding back and forth along the rug, and I kneel down to wrap one arm around his doggy shoulders. Frank, still whistling, slips on his deck shoes and slides his belt through its loops.

Don’t settle for less than the best, darling, my mother used to tell me, swishing her afternoon drink around the glass, and I haven’t, have I? Settled for less, that is. Frank’s the best there is. Just look at him. Aren’t I fortunate that my husband stays trim like that, when so many husbands let themselves go? When so many husbands allow their marital contentment to expand like round, firm balloons into their bellies. But Frank stays active. He walks to his office every day; he sails and swims and golfs and plays all the right sports, the ones with racquets. He has a tennis player’s body, five foot eleven without shoes, lean and efficient, nearly convex from hip bone to hip bone. A thing to watch, when he’s out on the court. Or in the swimming pool, for that matter, the one tucked discreetly in the crook of the Big House’s elbow, out of sight from both driveway and beach.

He shuts the wardrobe door and turns to me. “Are you sure you won’t come out on the water?”

“No, thanks. You go on ahead.” I rise from the rug and roll Percy’s silky ear around my fingers.

On his way to the door, Frank pauses to drop another kiss on my cheek, and for some reason—related perhaps to the photograph sitting in my drawer, related perhaps to the key in Frank’s suitcase, related perhaps to my sister or his grandmother or our lost baby or God knows—I clutch at the hand Frank places on my shoulder.

He tilts his head. “Everything all right, darling?”

There is no possibility, no universe existing in which I could tell him the truth. At my side, Percy lowers himself to the floor and thumps his tail against the rug, staring at the two of us as if a miraculous biscuit might drop from someone’s fingers at any moment.

I finger my pearls and smile serenely. “Perfectly fine, Frank. Drinks at six. Don’t forget.”

The smile Frank returns me is white and sure and minty fresh. He picks up my other hand and kisses it.

“As if I could.”

Caspian, 1964 (#ulink_217e0e13-54e3-5368-9102-7ad508266eba)

He avoided Boylan’s the next day, and the next. On the third day, he arrived at nine thirty, ordered coffee, and left at nine forty-five, feeling sick. He spent the day photographing bums near Long Wharf, and in the evening he picked up a girl at a bar and went back to her place in Charlestown. She poured them both shots of Jägermeister and unbuttoned his shirt. Outside the window, a neon sign flashed pink and blue on his skin. “Wow. Is that a scar?” she said, touching his shoulder, and he looked down at her false eyelashes, her smudged lips, her breasts sagging casually out of her brassiere, and he set down the glass untouched and walked out of the apartment.

He was no saint, God knew. But he wasn’t going to screw a girl in cold blood, not right there in the middle of peacetime Boston.

On the fourth day, he visited his grandmother in Brookline, in her handsome brick house that smelled of lilies and polish.

“It’s about time.” She offered him a thin-skinned cheek. “Have you eaten breakfast?”

“A while ago.” He kissed her and walked to the window. The street outside was lined with quiet trees and sunshine. It was the last day of the heat wave, so the weatherman said, and the last day was always the worst. The warmth shimmered upward from the pavement to wilt the new green leaves. A sleek black Cadillac cruised past, but his grandmother’s sash windows were so well made he didn’t even hear it. Or maybe his hearing was going. Too much noise.

“You and your early hours. I suppose you learned that in the army.”

“I was always an early riser, Granny.” He turned to her. She sat in her usual chintz chair near the bookcase, powdered and immaculate in a flamingo-colored dress that matched the flowers in the upholstery behind her.

“That’s your father’s blood, I suppose. Your mother always slept until noon.”

“I’ll take your word for it.”

“Trust me.” She reached for the bell on the small chinoiserie table next to the chair and rang it, a single ding. Granny wasn’t one for wallowing in grief, even for her oldest daughter. “What brings you out to see your old granny today?”

“No reason, except I’ll be shipping out on another tour soon.”

Her lip curled. “Why on earth?”

“Because I’m a soldier, Granny. It’s what I do.”

“There are plenty of other things you could do. Oh! Hetty. There you are. A tray of coffee for my grandson. He’s already eaten, but you might bring a little cake to sweeten him up.”

Right. As if he was the one who needed sweetening.

He waited until Hetty disappeared back through the living room doorway. “Like what, Granny? What can I do?”

“Oh, you know. Like your uncle’s firm. Or law school. I would say medicine, but you’re probably too old for all that song and dance, and anyway we already have a doctor in the family.”

“Anything but the army, in other words?” He leaned against the bookcase and crossed his arms. “Anything but following in my father’s footsteps?”

“I didn’t say that. Eisenhower was in the army, after all.”

“Give it a rest, Granny. You can’t stamp greatness on all our brows.”

“I didn’t say anything about greatness.”

“Poor Granny. It’s written all over your smile. But blood will out, you know. I tried all that in college, and look what happened.” He spread his hands. “You’ll just have to take me as you find me, I guess. Every family needs a black sheep. Gives us character. The press loves it, don’t they? Imagine the breathless TV feature, when Frank wins the nomination for president.”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake. You’re not a black sheep. Look at you.” She jabbed an impatient gesture at his reclining body, his sturdy legs crossed at the ankles. “I just worry about you, that’s all. Off on the other side of the word. Siam, of all places.”

“Vietnam.”

“At least you’re fighting Communists.”

“Someone’s got to do it.”

The door opened. Hetty sidled through, her long uniformed back warped under the weight of the coffee tray. He uncrossed his legs and pushed away from the wall to take it from her. He couldn’t stand the sight of it, never could—domestic servants lugging damned massive loads of coffee and cake for his convenience. At least in his father’s various accommodations, the trays were carried by sturdy young soldiers who were happy to be hauling coffee instead of grenades. A subtle difference, maybe, but one he could live with.

“Thank you, Hetty. What about this photography business of yours?” She waved him aside and poured him a cup of coffee with her own hands.

“It’s not a business. It’s a hobby. Not all that respectable, either, but surely I don’t need to tell you that?”

“It’s an art, Franklin says. Just like painting.”

“It’s not just like painting. But I guess there’s an art to it. You can say that to your friends, anyway, if it helps.” He took the coffee cup and resumed his position against the bookcase.

“Don’t you ever sit, young man?”

“Not if I can help it.”

“I guess that’s your trouble in a nutshell.”

He grinned and drank his coffee.

She made a grandmotherly harrumph, the kind of patronizing noise she’d probably sworn at age twenty—and he’d seen her pictures at age twenty, some rip-roaring New York party, Edith Wharton she wasn’t—that she would never, ever make. “You and that smile of yours. What about girls? I suppose you have a girl or two stringing along behind you, as usual.”

“Not really. I’m only back for a few weeks, remember?”

“That’s never stopped the men in this family before.” A smug smile from old Granny.

“And you’re proud of that?”

“Men should be men, girls should be girls. How God meant us.”

He shook his head. The cup rested in his palm, reminding him of Jane Doe’s curving elbow. “There is a girl, I guess.”

As soon as the words left his mouth, he realized she was the reason he came here to lily-scented Brookline that hot May morning, to its chintz upholstery and its shepherdess coffee service, to Granny herself, unchanged since his childhood.

Jane Doe. What to do with her. What to do with himself.

“What’s her name?” asked Granny.

He grinned again. “I don’t know. I’ve hardly spoken to her.”

“Hardly spoken to her?”

“I think she’s engaged.”

“Engaged, or married?”

“Engaged, I think. I didn’t see a band. Anyway, she doesn’t seem married.”

“Well, if she’s only engaged, there’s nothing to worry about.” Granny stirred in another spoonful of sugar. The silver tinkled expensively against the Meissen. “What kind of girl is she?”

“The nice kind.”

“Good family?”

“I told you, I don’t know her name.”

“Find out.”

“Hell, Granny, I—”

“Language, Caspian.”

He set down the coffee and strode back to the window. “Why the hell did I come here, anyway? I don’t know.”

“Don’t blaspheme. You can use whatever foul words you like in that … that platoon of yours, but you will not take the Lord’s name in vain in my house.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Now. To answer your question. Why did you come here? You came here to ask my advice, of course.”

“And what’s your advice, Granny?” he asked the window, the empty street outside, the identical white-trimmed Georgian pile of bricks staring back at him.

The silver clinked. Granny, cutting herself a slice of cake, placing it on a delicate shepherdess plate, taking a bite. “I am amazed, Caspian, so amazed and perplexed by the way your generation makes these things so unnecessarily complicated. The fact is, you only have one question to ask yourself, one question to answer before you do a single first thing.”

“Which is?”

“Do you want her for a wife or for a good time?”

The postman appeared suddenly, between a pair of trees on the opposite side of the street, wearing short pants and looking as if he might drop dead.

Caspian fingered the edge of the chintz curtain and considered the words good time, and the effortless way Granny spoke them. What the hell did Granny know about a good-time girl? Not that he wanted to know. Jesus. “There’s no in between?”

A short pause, thick with disapproval. “No.”

“All right. Then what?”

“Well, it depends. If you want a good time, you walk up to her, introduce yourself, and ask her to dinner.”

“Easy enough. And the other?”

Granny set down her plate. The house around them lay as still as outdoors, lifeless, empty now of the eight children she’d raised, the husband at his office downtown, if by office you meant mistress’s apartment. She was the lone survivor, the last man standing in the Brookline past. The floorboards vibrated beneath the carpet as she rose to her feet and walked toward him, at the same dragging tempo as the postman across the street.

She placed a hand on his shoulder, and he managed not to flinch.

“Now, don’t you know that, Caspian? You walk up, introduce yourself, and ask her to dinner.”

Tiny, 1966 (#ulink_d84325c6-8bb7-5ddf-827b-4834b09efae4)

At half past five o’clock, I push open the bottom sash of the bedroom window and prop my torso into the hot salt-laden air to look for my husband.

The beach is crammed with Hardcastle scions of all ages, running about the sand in skimpy swimsuits. Or frolicking: yes, that’s the word. A cluster of younger ones ply their shovels on a massive sand castle, assisted by a father or two; the younger teenagers are chasing one another, boys versus girls, testing out all those mysterious new frissons under the guise of play. Hadn’t I done that, between thirteen and sixteen, when the Schuylers summered on Long Island? I probably had. Or maybe my sisters had, and I’d watched from under my umbrella, reading a book, safe from freckles and sunburn and hormonal adolescent boys. Saving myself for greater things, or so I told myself, because that’s what Mums wanted for me. Greater things than untried pimply scions.

A cigarette trails from my fingers—another reason for opening the window—and I inhale quickly, in case anyone happens to be looking up.

Of the seven living Hardcastle children, six are here today with their spouses, and fully thirteen of Frank’s cousins have joined them in the pretty shingle and clapboard houses that make up the property. A compound, the magazines like to call it, as if it’s an armed camp, and the Hardcastles a diplomatic entity of their own. I know all their names. It’s part of my job. You’re the lady of the house now, Granny Hardcastle said, when we joined them on the Cape for the first time as a married couple. It was August, a week after we’d returned from our honeymoon, and boiling hot. Granny had moved out of the master suite while we were gone. You’re the lady of the house now, she told me, over drinks upon our arrival, and I thought I detected a note of triumph in her voice.

At the time, I’d also thought I must be mistaken.

You’re in charge, she went on. Do things exactly as you like. I won’t stick my nose in, I promise, unless you need a little help from time to time.

I spot Frank, tucking up the boat in the shelter of the breakwater, a couple of hundred yards down the shore. At least I assume it’s Frank; the boat is certainly his, the biggest one, the tallest mast. At one point he meant to train seriously for the America’s Cup. I don’t know what became of that one. Too much career in the way, I suppose, too much serious business to get on with. There are two of them, Frank and someone else, tying the Sweet Christina up to her buoy. No use calling for him, at this distance.

I draw in a last smoke, crush out the cigarette on the windowsill, and check my watch. Five thirty-five, and no one’s getting ready for drinks. Everyone’s out enjoying the beach, the sun, the sand. Below me, Pepper reclines on a beach chair, bikini glowing, head scarf fluttering, every inch of her slathered in oil. Pepper has olive skin, so she can do things like that; she can bare her shapely coconut-oiled limbs to the sun and come out golden. She’s not hiding her cigarette, either: it’s out there in plain sight of men, women, and children. Along with a thermos of whatever.

Everybody’s having a sun-swept good time.

Well, good for them. That’s what the Cape is for, isn’t it? That’s why the Hardcastles bought this place, back in the early twenties, when beach houses were becoming all the rage. Why they keep it. Why they gather together here, year after year, eating the same lobster rolls and baking under the same sweaty sun.

Just before I duck back into the bedroom, a primal human instinct turns my head to the left, and I catch sight of a face staring up from the sand.

For an instant, my heart crashes. Giddy. Terrified. Caught.

But it’s only Tom. Constance’s husband, Tom, a doctoral student in folk studies—whatever that was—at Tufts and now at leisure for the whole lazy length of the summer, with nothing to do but collect his trust fund check, tweak his thesis, and get Constance pregnant again. He sits in the dunes near the house, smoking and disgruntled, and that disgruntled face just so happens to be observing me as if I’m the very folk whereof he studies. He’s probably seen my unfastened dress. He’s probably seen the cigarette. He’ll probably tattle on me to Constance.

Little weasel.

I smile and wave. He salutes me with his cigarette.

I withdraw and pretzel myself before the mirror to wiggle up the zipper on my own. (A snug bodice, miniature sleeves just off the shoulder: really, where was a husband when you needed him? Oh, of course: tying up his yacht.) I swipe on my lipstick, blot, and swipe again. My hair isn’t quite right; I suppose I need a cut. So hard to remember these things, out here on the Cape. It’s too late for curlers. I wind the ends around my fingers, hold, release. Repeat. Fluff. The room lies silent around me. Even Percy has dozed quietly off.

As I finger my way around my head, the face in the mirror seems to be frowning in me. The way my mother—passing me by one evening on her way to someone’s party—warned me never to do, because my skin might freeze that way.

Wrinkles. The bitter enemy of a woman’s happiness.

Frank bursts through the door, smiling and wind whipped, at ten minutes to six, a moment too late to fasten my diamond and aquamarine necklace for me.

“Had a nice sail?” I say icily.

“The best. Cap joined me. Just like old times, when we were kids. Went all the way around the point and back. Record time, I’ll bet. Goddamn, that man can sail.” The highest possible praise. He blows straight past me to the bathroom.

“Even with one leg?” I call out.

“It worked for Bluebeard, didn’t it?” He laughs at his own joke.

I screw on the last earring and give the hair a last pat. “I’m needed downstairs. Can you manage by yourself?”

Frank walks out of the bathroom to rummage in his wardrobe. “Fine, fine.” His head pokes around the corner of the door. “Need help with your zipper or anything?”

My shoes sit next to the door, aquamarine satin to match my dress and jewelry, two-inch heels. I slip my feet into one and the other. The added height goes straight to my head.

“No,” I say. “I don’t need any help.”

On my way downstairs, I stop to check on Pepper.

“Come in,” she says in reply to my knock, and I push open the door to find her belting her robe over her body. I have the impression, based on nothing but instinct, that she’s been standing naked in front of the mirror in the corner. It’s something Pepper would do, admiring her figure, which (like that of our youngest sister Vivian) belongs to a different species of figures from mine: tall, curved like a violin, colored by the same honey varnish. It’s the kind of figure that inspires men to maddened adoration, especially when she drapes those violin curves as she usually does, in short tangerine dresses and heeled slippers.

All at once, I feel flat and pale and straight-hipped in my aquamarine satin, too small, insignificant. A prissed-up girl, instead of a woman: a rigid frigid little lady. What’s happened to me? My God.

“Aren’t you dressed yet?” I ask.

“I’ve just come in from the beach. So hard to leave. I haven’t lain out on a beach in ages.”

“All work and no play?”

“Oh, you know me.” She laughs. “It’s killing me, this crazy Washington life. It’s so lovely to be idle again. I know you’re used to it, but …” She turns away in the middle of an eloquent shrug and looks out the window.

“Not that idle.”

“A lady of leisure, just like Mums. I can’t tell you how jealous I am.” She stretches her arms above her head, right there before the window, not jealous at all. Nor in any hurry to dress herself for the party, apparently.

I cast a significant glance at my watch. “I’m on my way down, actually. Can I help you with anything? Zipper?”

She turns back.

“No, thanks. I can manage. There’s not much to zip, anyway.” Another low and throaty laugh, and then a sniff, incredulous. “Tiny! Have you been smoking?”

As she might say swinging.

I consider lying. “Just one,” I say, flicking a disdainful hand.

“Good Lord. I never thought I’d see the day. Poor thing. I guess this family of yours would drive anyone to debauchery. Don’t worry.” She zips her lips. “I won’t say a word to Mums. Is Major Gorgeous here yet?”

“Nobody’s here yet. We still have a few minutes.”

“You sound awfully cold, Tiny. Maybe you should sit out on the beach for a few minutes and warm up your blood. It works wonders, believe me.”

I gaze at my sister’s playful eyes, tilted alluringly at the corners. Her curving red mouth. The old Pepper, now that it’s just the two of us, alone in her room. Her claws, my skin. We do so much better when there are others around. Someone else’s family to distract us, someone else’s irreversible birth order: flawless first, naughty second, locked in timeless conflict.

At my silence, Pepper pulls the ends of her robe more closely together. “So. I saw your husband and the major out there on the water, sailing a boat. Did you get your après-midi after all? It must have been a quick one. Not that those aren’t sometimes the best.”

“Actually, I had another miscarriage eight days ago,” I say. “I don’t know if Mums told you. So, no. No après-midi for a few more weeks yet, unfortunately. Quick or not.”

Pepper’s arms uncross at last. Her tip-tilted eyes—the dark blue Schuyler eyes she shares with Vivian, except that hers are a shade or two lighter—go round with sympathy. “Oh, Tiny! Of course I didn’t know. I’m so sorry. What a bitch I am.”

I turn to the door. “It’s all right. Really.”

“My big fat mouth …”

“You have a lovely mouth, Pepper. I’m going downstairs now to make sure everything’s ready. Let me know if you need anything.”

“Tiny—”

I close the door carefully behind me.

Downstairs, everything is perfect, exactly as I left it three quarters of an hour ago. The vases are full of hyacinths—my first order, as lady of the compound, was nothing short of rebellion: I changed the house flower from lily to hyacinth, never mind the financial ruin when hyacinths were out of season—and the side tables are lined with coasters. All the windows and French doors have been thrown open, heedless of bugs, because the heat’s been building all day, hot layered on hot, and the Big House has no air-conditioning. Mrs. Crane and the two maids are busy in the kitchen, filling trays with Ritz crackers and crab dip. If this were a party for outside guests, I’d have hired a man from town, put him in a tuxedo, and had him pour drinks from the bar. But this is only family, and Frank and his father can do it themselves.

Frank’s father. He rises from his favorite chair in the library, immaculate in a white dinner jacket and black tie, his graying hair polished into silver. “Good evening, Tiny. You look marvelous, as always.”

I lean in for his kiss. “So do you, Mr. Hardcastle. Enjoying your last moment of peace?”

He holds up his cigar, his glass of Scotch. “Guilty as charged. Anybody here yet?”

“I think we’ll be running late. I stuck my head out the window at five thirty, and nobody was stirring from the beach.”

“It’s a hot day.”

“Yes, it is. At least it gives us a few moments to relax before everyone arrives.”

“Indeed. Can I get you a drink?” He moves to the cabinet.

“Yes, please. Vodka martini. Dry, olive.”

He moves competently about the bottles and shakers, mixing my martini. You might be wondering why Frank’s mother isn’t the lady of the house instead of me, organizing its dinner parties, decreeing the house flower, and you might suspect she’s passed away, though of course you’re too tactful to ask. Well, you’re wrong. In fact, the Hardcastles divorced when Frank was five or six, I can’t remember exactly, but it was a terrible scandal and crushed Mr. Hardcastle’s own political ambitions in a stroke. You can’t run for Senate if you’re divorced, after all, or at least you couldn’t back in the forties. The torch was quietly tossed across the generation to my husband. Oh, and the ex–Mrs. Hardcastle? I’ve never been told why they divorced, and her name isn’t spoken around the exquisite hyacinth air of the Big House. I’ve never even met her. She lives in New York. Frank visits her sometimes, in her exile, when he’s there on business.

There is a distant ring of the doorbell. The first guests. I glance up at the antique ormolu clock above the mantel. Five fifty-nine.

“Thank you.” I accept the martini from my father-in-law and turn to leave. “If you’ll excuse me. It looks like somebody in this family has a basic respect for punctuality, after all.”

I nearly reach the foyer before it occurs to me to wonder why a Hardcastle would bother to ring the doorbell of the Big House, and by that time it’s too late.

Caspian Harrison stands before me in his dress uniform, handing his hat to Mrs. Crane. He looks up at my entrance, my shocked halt, and all I can see is the scar above his left eyebrow, wrapping around the curve of his temple, which was somehow hidden on the television screen by the angle or the bright sunshine of the White House Rose Garden.

A few drops of vodka spill over the rim of the glass and onto my index finger.

“Major Harrison.” I lick away the spilled vodka and smile my best hostess smile. “Welcome home.”

Caspian, 1964 (#ulink_a3adf114-6c88-5374-99d8-8f69aa8e7d72)

When Cap arrived at the coffee shop the next morning, nine thirty sharp, the place was jammed. Em rushed by with an armful of greasy plates.

“What gives?” he called after her.

“Who knows? There’s one booth left in the corner, if you move fast.”

He looked around and found it, the booth in the corner, and moved fast across the sweaty bacon-and-toast air to sling himself and his camera bag along one cushion. Em scooted over and set a cup of coffee and a glass of orange juice on the table, almost without stopping. He drank the coffee first, hot and crisp. You had to hand it to Boylan’s. Best coffee in Back Bay, if you liked the kind of coffee you could stand your spoon in.

He leaned against the cushion and watched the hustle-bustle. A lot of regulars this morning, a few new faces. Em and Patty cross and recross the linoleum in patterns of chaotic efficiency, hair wisping, stockings sturdy. Outside, the pavement still gleamed with the rain that had poured down last night, shattering the heat wave in a biblical deluge, flooding through the gutters and into the bay. Maybe that was why Boylan’s booths were so full this morning. That charge of energy when the cool air bursts at last through your open window and interrupts your lethargy. Blows apart your accustomed pattern.

“What’ll it be, Cap? The usual?” Em stood at the edge of the table, holding a coffeepot and a plate of steaming pancakes. They had an uncomplicated relationship, he and Em; no menus required.

“Well, now …”

“If you love me, Cap, make it snappy.”

“Bacon, four eggs over easy, lots of toast.”

“Hungry?” She was already dashing off.

“You could—” Em was gone. “—say that.” Across the crowd, someone dropped a cup loudly into its saucer, making him jolt. He converted the movement into a stretch—nothing to see here, folks, no soldier making an idiot of himself—and plucked the paperback from his camera bag, but before he could settle himself on the page the goddamned bells jangled again, clawing on his nerves like a black cat, and he jerked toward the door.

His chest expanded and deflated.

Well, well. Jane Doe. Of all the girls.

She took off her sunglasses to reveal an expression of utter, utter dismay. (With another girl he might simply have said total dismay.) Her shiny dark hair bobbed about her ears as she looked one way and the other, searching for a booth around which to enact her invisible force field. She wore a berry-red dress, sleeveless, a white cardigan pulled around her shoulders. Her face glowed with recent exercise, making him think instantly of sex (vigorous, sweaty morning sex on white sheets, while the early sunlight poured through the window, and a long hot shower afterward that might just end up in more sex, if luck were a lady, and if the lady could still walk).

Em passed by. Miss Doe tapped her on the elbow and asked her a question; Em replied with a helpless shrug and moved on.

Miss Doe’s elegant eyebrows converged to a cranky point. She had expected better than this. To her left, a sandy-haired boy about four years old started up a tantrum, a real grand mal, no holds barred, a thrashing, howling fit-to-be-tied fit over a glass of spilled milk. In the same instant, the door opened behind her, and a large man barged through, smack between Miss Doe’s white cardiganed shoulder blades. She staggered forward, clutching her pocketbook, while the man maneuvered around her and called for Em in a loud Boston twang.

At which point, Cap raised his hand into the crowded air.

Not a wave. Not a beckoning of the fingers. Just a single hand, lifted up above the sea of heads, the way he might signal noiselessly to another soldier in the jungle. I’m here, buddy. At your back. Never fear.

Miss Doe wasn’t a soldier. She saw his hand and ducked her head swiftly, pretending she hadn’t noticed. But an instant later, her eyes returned to his corner. He lowered the hand and shrugged, pretending he didn’t care.

But his heart was bouncing off his rib cage, and it wasn’t just the crash of the coffee cup and the jingle of bells. Miss Doe was slender and gently curved, almost boyish, not his preferred figure at all, and still he couldn’t remove his mind from the belly of that berry-red dress, the tiny pleats at her tiny waist, the rise of her breasts below the straight edge of her collar. The pink curve of her lips, slightly parted. The suggestive flush of her cheeks. Flushed with what? Did she spend the night with her fiancé? Did she shed her immaculate clothes for him, her immaculate hair and lipstick? Did she let down her force field and allow him inside?

What was she like, inside her force field?

She lifted an uncertain eyebrow. He held up his hands before his chest, palms out, and sent her his best crooked smile, the one that never failed. No threat here. Just helping a girl out, the goodness of his heart.

Miss Doe hoisted her pocketbook up her shoulder, the same gesture as before, and walked poker-faced toward his booth. He liked the way she moved, sinuous and gymnastic in her matching berry-red kitten heels, not the usual mincing gait you saw around town. Girls with no stride at all, no swing, no natural grace.

You could always see the real girl in her walk, couldn’t you? The one thing she couldn’t make over.

She arrived at the booth, smelling of Chanel.

“Caspian,” he said, without standing up.

She slid in across from him, holding her dress beneath her. She settled her pocketbook on the seat, well away from his grasp, and folded her hands on the edge of the table. Her engagement ring glittered just so in the yellow light from the hanging lamp. Mother of God. Three carats at least. Almost as big as his grandmother’s rock.

“Tiny,” she said.

“Tiny?” he said. “Is that a nickname?”

She fixed him a steely one. “Yes, it is.”

She studied the menu carefully, considered each item, and raised her head at last to order her usual coffee and an apricot Danish. Em hid a smile and scooted obediently off, tucking her pencil between her ear and her graying brown hair. She scooted right on past the boy with the tantrum and his harried mother, who cajoled and scolded in alternating beats.

“Please go ahead,” Tiny said, gesturing to Cap’s plate. “Don’t let it go cold on my account.”

“I won’t.” He picked up his fork with one hand and his paperback with the other, and commenced—against every instinct, ground in him since childhood—to shovel and read, having rolled the cover carefully around the back so she couldn’t see the title.