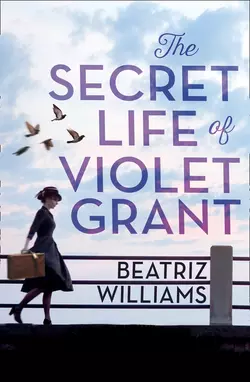

The Secret Life of Violet Grant

Beatriz Williams

From the New York Times bestselling author of The Wicked City: a story of love and intrigue that travels from Kennedy-era Manhattan to World War I Europe…Fresh from college, irrepressible Vivian Schuyler defies her wealthy Fifth Avenue family to work at cut-throat Metropolitan magazine. But this is 1964, and the editor dismisses her…until a parcel lands on Vivian’s Greenwich Village doorstep that starts a journey into the life of an aunt she never knew, who might give her just the story she’s been waiting for.In 1912, Violet Schuyler Grant moved to Europe to study physics, and made a disastrous marriage to a philandering fellow scientist. As the continent edges closer to the brink of war, a charismatic British army captain enters her life, drawing her into an audacious gamble that could lead to happiness…or disaster.Fifty years later, Violet’s ultimate fate remains shrouded in mystery. But the more obsessively Vivian investigates her disappearing aunt, the more she realizes all they have in common – and that Violet’s secret life is about to collide with hers.

Copyright (#ulink_01d719a7-3de7-50b1-8572-c139bcef96b5)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by Putnam, Penguin USA 2014

First published in the UK by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Beatriz Williams 2014

Cover design by TBC © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © TBC

Beatriz Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780399162176

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780008134983

Version: 2017-08-18

Dedication (#ude9b6448-d0c0-5180-9aa6-bf1e10c135c8)

To my beautiful grandmother,

Sarena Merle Baker

1924–2013

Contents

Cover (#u30b5104b-bb2b-564a-9b13-6f6610189b7b)

Title Page (#uee8e8673-06b6-5b3b-914c-a9e6160d79b3)

Copyright (#u421a47dc-0d3e-56aa-90dc-5597a386dff9)

Dedication

Prologue (#u7f5c650e-3966-55ff-9856-e7d017bbbe5f)

Part One (#u53dfec59-19c2-54c9-b7c6-8447f27c3991)

Vivian, 1964: New York City (#u8f86a5c1-0a42-54b7-ba0a-714518c754e5)

Violet, 1914: Berlin (#u30664f94-9126-5265-9e67-05d4cf4fb8d4)

Vivian (#ua00083e4-2793-587f-a021-f7bde82a4c75)

Violet (#u06830ec3-1ab9-5bcf-bc77-c7a548d2f8aa)

Vivian (#u96e18cc8-b8bc-5079-8796-8ca84486584e)

Violet (#ua0e9ead9-445b-5726-9c76-cb7918e4cb3a)

Vivian (#udd7ea6f5-b173-59da-8701-c18c4420a7fc)

Violet (#ufcd90a3f-d660-5b66-a8b7-59c8d1e4ca6c)

Vivian (#u7a46251d-1d4e-562e-aa05-6f59d248acf7)

Violet (#ue0ab42b9-bc25-5aba-9307-06fc176b444b)

Vivian (#u6994a608-f004-5782-9b57-c382f7c5ab08)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Interlude: Violet, 1912 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet, 1914 (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet, 1914 (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet (#litres_trial_promo)

Vivian (#litres_trial_promo)

Aftermath (#litres_trial_promo)

Lionel, 1914 (#litres_trial_promo)

Violet, 1964 (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Beatriz Williams (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

In the summer of 1914, a beautiful thirty-eight-year-old American divorcée named Caroline Thompson took her twenty-two-year-old son, Mr. Henry Elliott, on a tour of Europe to celebrate his recent graduation from Princeton University.

The outbreak of the First World War turned the family into refugees, and according to legend, Mrs. Thompson ingeniously negotiated her own fair person in exchange for safe passage across the final border from Germany.

A suitcase, however, was inadvertently left behind.

In 1950, the German government tracked down a surprised Mr. Elliott and issued him a check in the amount of one hundred deutsche marks as compensation for “lost luggage.”

This is not their story.

(#ulink_2c7d8d65-f92b-5124-9474-8eab4913d397)

Vivian, 1964 (#ulink_bd5ac879-bf2e-5dab-8007-ef679dfbc04a)

NEW YORK CITY (#ulink_bd5ac879-bf2e-5dab-8007-ef679dfbc04a)

I nearly missed that card from the post office, stuck up as it was against the side of the mail slot. Just imagine. Of such little accidents is history made.

I’d moved into the apartment only a week ago, and I didn’t know all the little tricks yet: the way the water collects in a slight depression below the bottom step on rainy days, causing you to slip on the chipped marble tiles if you aren’t careful; the way the butcher’s boy steps inside the superintendent’s apartment at five-fifteen on Wednesday afternoons, when the super’s shift runs late at the cigar factory, and spends twenty minutes jiggling his sausage with the super’s wife while the chops sit unguarded in the vestibule.

And—this is important, now—the way postcards have a habit of sticking to the side of the mail slot, just out of view if you’re bending to retrieve your mail instead of crouching all the way down, as I did that Friday evening after work, not wanting to soil my new coat on the perpetually filthy floor.

But luck or fate or God intervened. My fingers found the postcard, even if my eyes didn’t. And though I tossed the mail on the table when I burst into the apartment and didn’t sort through it all until late Saturday morning, wrapped in my dressing gown, drinking a filthy concoction of tomato juice and the-devil-knew-what to counteract the several martinis and one neat Scotch I’d drunk the night before, not even I, Vivian Schuyler, could elude the wicked ways of the higher powers forever.

Mind you, I’m not here to complain.

“What’s that?” asked my roommate, Sally, from the sofa, such as it was. The dear little tart appeared even more horizontally inclined than I did. My face was merely sallow; hers was chartreuse.

“Card from the post office.” I turned it over in my hand. “There’s a parcel waiting.”

“For you or for me?”

“For me.”

“Well, thank God for that, anyway.”

I looked at the card. I looked at the clock. I had twenty-three minutes until the post office on West Tenth Street closed for the weekend. My hair was unbrushed, my face bare, my mouth still coated in a sticky film of hangover and tomato juice.

On the other hand: a parcel. Who could resist a parcel? A mysterious one, yet. All sorts of brown-paper possibilities danced in my head. Too early for Christmas, too late for my twenty-first birthday (too late for my twenty-second, if you’re going to split hairs), too uncharacteristic to come from my parents. But there it was, misspelled in cheap purple ink: Miss Vivien Schuyler, 52 Christopher Street, apt. 5C, New York City. I’d been here only a week. Who would have mailed me a parcel already? Perhaps my great-aunt Julie, submitting a housewarming gift? In which case I’d have to skedaddle on down to the P.O. hasty-posty before somebody there drank my parcel.

The clock again. Twenty-two minutes.

“If you’re going,” said Sally, hand draped over her eyes, “you’d better go now.”

Of such little choices is history made.

I DARTED into the post office building at eight minutes to twelve—yes, my dears, I have good reason to remember the exact time of arrival—shook off the rain from my umbrella, and caught my sinking heart at the last instant. The place was crammed. Not only crammed, but wet. Not only wet, but stinking wet: sour wool overlaid by piss overlaid by cigarettes. I folded my umbrella and joined the line behind a blond-haired man in blue surgical scrubs. This was New York, after all: you took the smell and the humanity—oh, the humanity!—as part of the whole sublime package.

Well, all right.

Amendment: You didn’t have to take the smell and the humanity and the ratty Greenwich Village apartment with the horny butcher’s boy on Wednesday afternoons and the beautifully alcoholic roommate who might just pick up the occasional weekend client to keep body and Givenchy together. Not if you were Miss Vivian Schuyler, late of Park Avenue and East Hampton, even later of Bryn Mawr College of Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. In fact, you courted astonishment and not a little scorn by so choosing. Picture us all, the affectionate Schuylers, lounging about the breakfast table with our eggs and Bloody Marys at eleven o’clock in the morning, as the summer sun melts like honey through the windows and the uniformed maid delivers a fresh batch of toast to absorb the arsenic.

Mums (lovingly): You aren’t really going to take that filthy job at the magazine, are you?

Me: Why, yes. I really am.

Dadums (tenderly): Only bitches work, Vivian.

So it was my own fault that I found myself standing there in the piss-scented post office on West Tenth Street, with my elegant Schuyler nose pressed up between the shoulder blades of the blue scrubs in front of me. I just couldn’t leave well enough alone. Could not accept my gilded lot. Could not turn this unearned Schuyler privilege into the least necessary degree of satisfaction.

And less satisfied by the moment, really, as the clock counted down to quitting time and the clerks showed no signs of hurry and the line showed no sign of advancing. The foot-shifting began. The man behind me swore and lit a cigarette. Someone let loose a theatrical sigh. I inched my nose a little deeper toward the olfactory oasis of the blue scrubs, because this man at least smelled of disinfectant instead of piss, and blond was my favorite color.

A customer left the counter. The first man in line launched himself toward the clerk. The rest of us took a united step forward.

Except the man in blue scrubs. His brown leather feet remained planted, but I realized this only after I’d thrust myself into the center of his back and knocked him right smack down to the stained linoleum.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, holding out my hand. He looked up at me and blinked, like my childhood dog Quincy used to do when roused unexpectedly from his after-breakfast beauty snooze. “My word. Were you asleep?”

He ignored my hand and rose to his feet. “Looks that way.”

“I’m very sorry. Are you all right?”

“Yes, thanks.” That was all. He turned and faced front.

Well, I would have dropped it right there, but the man was eye-wateringly handsome, stop-in-your-tracks handsome, Paul Newman handsome, sunny blue eyes and sunny blond hair, and this was New York, where you took your opportunities wherever you found them. “Ah. You must be an intern or a resident, or whatever they are. Saint Vincent’s, is it? I’ve heard they keep you poor boys up three days at a stretch. Are you sure you’re all right?”

“Yes.” Taciturn. But he was blushing, right the way up his sweet sunny neck.

“Unless you’re narcoleptic,” I went on. “It’s fine, really. You can admit it. My second cousin Richard was like that. He fell asleep at his own wedding, right there at the altar. The organist was so rattled she switched from the Wedding March to the Death March.”

The old pregnant pause. Someone stifled a laugh behind me. I thought I’d overplayed my hand, and then:

“He did not.”

Nice voice. Sort of Bing Crosby with a bass chord.

“Did too. We had to sprinkle him with holy water to wake him up, and by sprinkle I mean tip-turn the whole basin over his head. He’s the only one in the family to have been baptized twice.”

The counter shed two more people. We were cooking now. I glanced at the lopsided black-and-white clock on the wall: two minutes to twelve. Blue Scrubs still wasn’t looking at me, but I could see from his sturdy jaw—lanterns, psht—he was trying very hard not to smile.

“Hence his nickname, Holy Dick,” I said.

“Give it up, lady,” muttered the man behind me.

“And then there’s my aunt Mildred. You can’t wake her up at all. She settled in for an afternoon nap once and didn’t come downstairs again until bridge the next day.”

No answer.

“So, during the night, we switched the furniture in her room with the red bordello set in the attic,” I said, undaunted. “She was so shaken, she led an unsupported ace against a suit contract.”

The neck above the blue scrubs was now as red as tomato bisque, minus the oyster crackers. He lifted one hand to his mouth and coughed delicately.

“We called her Aunt van Winkle.”

The shoulder blades shivered.

“I’m just trying to tell you, you have no cause for embarrassment for your little disorder,” I said. “These things can happen to anyone.”

“Next,” said a counter clerk, eminently bored.

Blue Scrubs leapt forward. My time was up.

I looked regretfully down the row of counter stations and saw, to my dismay, that all except one were now fronted by malicious little engraved signs reading COUNTER CLOSED.

The one man remaining—other than Blue Scrubs, who was having a pair of letters weighed for air mail, not that I was taking note of any details whatsoever—stood fatly at the last open counter, locked in a spirited discussion with the clerk regarding his proficiency with brown paper and Scotch tape.

Man (affectionately): YOU WANT I SHOULD JUMP THE COUNTER AND BREAK YOUR KNEECAPS, GOOBER?

Clerk (amused): YOU WANT I SHOULD CALL THE COPS, MORON?

I checked my watch. One minute to go. Behind me, I heard people sighing and breaking away, the weighty doors opening and closing, the snatches of merciless October rain on the sidewalk.

Ahead, the man threw up his hands, grabbed back his ramshackle package, and stormed off.

I took a step. The clerk stared at me, looked at the clock, and took out a silver sign engraved COUNTER CLOSED.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I said.

The clerk smiled, tapped his watch, and walked away.

“Excuse me,” I called out, “I’d like to see the manager. I’ve been waiting here for ages, I have a very urgent parcel—”

The clerk turned his head. “It’s noon, lady. The post office is closed. See you Monday.”

“I will not see you Monday. I demand my parcel.”

“Do you want me to call the manager, lady?”

“Yes. Yes, I should very much like you to call the manager. I should very much—”

Blue Scrubs looked up from his air-mail envelopes. “Excuse me.”

I planted my hands on my hips. “I’m terribly sorry to disturb the serenity of your transaction, sir, but some of us aren’t lucky enough to catch the very last post-office clerk before the gong sounds at noon. Some of us are going to have to wait until Monday morning to receive our rightful parcels—”

“Give it a rest, lady,” said the clerk.

“I’m not going to give it a rest. I pay my taxes. I buy my stamps and lick them myself, God help me. I’m not going to stand for this kind of lousy service, not for a single—”

“That’s it,” said the clerk.

“No, that’s not it. I haven’t even started—”

“Look here,” said Blue Scrubs.

I turned my head. “You stay out of this, Blue Scrubs. I’m trying to conduct a perfectly civilized argument with a perfectly uncivil post-office employee—”

He cleared his Bing Crosby throat. His eyes matched his scrubs, too blue to be real. “I was only going to say, it seems there’s been a mistake made here. This young lady was ahead of me in line. I apologize, Miss …”

“Schuyler,” I whispered.

“… Miss Schuyler, for being so very rude as to jump in front of you.” He stepped back from the counter and waved me in.

And then he smiled, all crinkly and Paul Newman, and I could have sworn a little sparkle flashed out from his white teeth.

“Since you put it that way,” I said.

“I do.”

I drifted past him to the counter and held out my card. “I think I have a parcel.”

“You think you have a parcel?” The clerk smirked.

Yes. Smirked. At me.

Well! I shook the card at his post-office smirk, nice and sassy. “That’s Miss Vivian Schuyler on Christopher Street. Make it snappy.”

“Make it snappy, please,” said Blue Scrubs.

“Please. With whipped cream and a cherry,” I said.

The clerk snatched the card and stalked to the back.

My hero cleared his throat.

“My name isn’t Blue Scrubs, by the way,” he said. “It’s Paul.”

“Paul?” I tested the word on my tongue to make sure I’d really heard it. “You don’t say.”

“Is that a problem?

I liked the way his eyebrows lifted. I liked his eyebrows, a few shades darker than his hair, slashing sturdily above his eyes, ever so blue. “No, no. Actually, it suits you.” Smile, Vivian. I held out my hand. “Vivian Schuyler.”

“Of Christopher Street.” He took my hand and sort of held it there, no shaking allowed.

“Oh, you heard that?”

“Lady, the whole building heard that,” said the clerk, returning to the counter. Well. He might have been the clerk. From my vantage, it seemed as if an enormous brown box had sprouted legs and arms and learned to walk, a square-bellied Mr. Potato Head.

“Great guns,” I said. “Is that for me?”

“No, it’s for the Queen of Sheba.” The parcel landed before me with enough heft to rattle all the little silver COUNTER CLOSED signs for miles around. “Sign here.”

“Just how am I supposed to get this box back to my apartment?”

“Your problem, lady. Sign.”

I maneuvered my hand around Big Bertha and signed the slip of paper. “Do you have one of those little hand trucks for me?”

“Oh, yeah, lady. And a basket of fruit to welcome home the new arrival. Now get this thing off my counter, will you?”

I looped my pocketbook over my elbow and wrapped my arms around the parcel. “Some people.”

“Look, can I help you with that?” asked Paul.

“No, no. I can manage.” I slid the parcel off the counter and staggered backward. “On the other hand, if you’re not busy saving any lives at the moment …”

Paul plucked the parcel from my arms, not without brushing my fingers first, almost as if by accident. “After all, I already know where you live. If I’m a homicidal psychopath, it’s too late for regrets.”

“Excellent diagnosis, Dr. Paul. You’ll find the knives in the kitchen drawer next to the icebox, by the way.”

He hoisted the massive box to his shoulder. “Thanks for the tip. Lead on.”

“Just don’t fall asleep on the way.”

GIDDY might have been too strong a word for my state of mind as I led my spanking new friend home with my spanking new parcel, but not by much. New York complied agreeably with my mood. The crumbling stoops gleamed with rain; the air had taken on that lightening quality of a storm on the point of lifting.

Mind you. I still took care to stand close, so I could hold my umbrella over the good doctor’s glowing blond head.

“Why didn’t you wear a coat, at least?” I tried to sound scolding, but my heart wasn’t in it.

“I just meant to dash out. I didn’t realize it was raining; I hadn’t been outside for a day and a half.”

I whistled. “Nice life you’ve made for yourself.”

“Isn’t it, though.”

We turned the corner of Christopher Street. The door stood open at my favorite delicatessen, sending a friendly matzo-ball welcome into the air. Next door, the Apple Tree stood quiet and shuttered, waiting for Manhattan’s classiest queens to liven it up by night. My neighborhood. I loved it already; I loved it even more at this moment. I loved the whole damned city. Where else but New York would a Doctor Paul pop up in your post office, packaged in blue scrubs, fully assembled and with high-voltage batteries included free of charge?

By the time we reached my building, the rain had stopped entirely, and the droplets glittered with sunshine on the turning leaves. I whisked my umbrella aside and winked an affectionate hello to the grime in the creases of the front door. The lock gave way with only a rusty minimum of rattling. Doctor Paul ducked below the lintel and paused in the vestibule. A patch of new sunlight shone through the transom onto his hair. I nearly wept.

“This is you?” he said.

“Only good girls live at the Barbizon. Did I mention I’m on the fifth floor?”

“Of course you are.” He turned his doughty shoulders to the stairwell and began to climb. I followed his blue-scrubbed derriere upward, marveling anew as we achieved each landing, wondering when my alarm clock would clamor through the rainbows and unicorns and I would open my eyes to the tea-stained ceiling above my bed.

“May I ask what unconscionably heavy apparatus I’m carrying up to your attic? Cast-iron stove? Cadaver?”

Oh! The parcel.

“My money’s on the cadaver.”

“You don’t know?”

“I have no idea. I don’t even know who it’s from.”

He rested his foot on the next step and cocked his head toward the box. “No ticking, anyway. That’s a good sign.”

“No funny smell, either.”

He resumed the climb with a precious little flex of his shoulder. The landscape grew more dismal as we went, until the luxurious rips in the chintz wallpaper and the incandescent nakedness of the lightbulbs announced that we had reached the unsavory entrance to my unsuitable abode. I made a swift calculation of dishes left unwashed and roommates left unclothed.

“You know, you could just leave it right here on the landing,” I said. “I can manage from here.”

“Just open the door, will you?”

“So commanding.” I shoved the key in the lock and opened the door.

Well, it could have been worse. The dishes had disappeared—sink, perhaps?—and so had the roommate. Only the bottle of vodka remained, sitting proudly on the radiator shelf next to the tomato juice and an elegant black lace slip. Sally’s, by my sacred honor. I hurried over and draped my scarf over the shameful tableau.

A thump ensued as Doctor Paul laid the parcel to rest on the table. “Whew. I thought I wasn’t going to make it up that last flight.”

“Don’t worry. I would have caught you.”

He was looking at the parcel: one hand on his hip, the other raking through his hair in that way we girls adore. “Well?”

“Well, what?”

“Aren’t you going to open it?”

“It’s my parcel. Can’t a girl have a little privacy?”

“Now, see here. I carried that … that object up five flights of Manhattan stairs. Can’t a man have a little curiosity?”

Again with the glittery smile. I pushed myself off the radiator. “Since you put it that way. Make yourself comfortable. Can I take your coat and hat?”

“That hurt.”

I slipped off my wet raincoat and slung it on Sally’s hat tree, a hundred years old at least and undoubtedly purloined. I placed my hat on the hook above my coat, taking care to give my curls an artful little shake. Well, you can’t blame me for that, at least. My hair was my best feature: brown and glossy, a hint of red, falling just so around my ears, a saucy flip. It distracted from my multitude of flaws, Monday to Sunday. Why not shake for all I was worth?

I turned around and sashayed the two steps to the table. Also purloined. Sally had told me the story yesterday, over our second round of martinis: the restaurant owner, the jealous wife, the police raid. I’ll spare you the ugly details. In any case, our table was far more important than either of us had a right to own—solid, square, genuine imitation wood—which now proved positively providential, because my mysterious gift from the post office (the parcel, not the blonde) would have overwhelmed a lesser piece of furniture. As it was, the beast sat brown and hulking in the center, battered in one corner, stained in another, patched with an assortment of foreign stamps.

“Well, well.” I peered over the top. “What have we here?”

Miss Vivian Schuyler, read the label. Of 52 Christopher Street, et cetera, et cetera, except that my first name appeared over a scribbled-out original, and my building address likewise.

“It looks as if it’s been forwarded,” I said.

“The plot thickens.”

“My mother’s handwriting.” I ran my finger over the jagged remains of Fifth Avenue. “My parents’ address, too.”

“That sounds reasonable.” He remained a few respectful feet away, arms crossed against his blue chest. “Someone must have sent it to your parents’ house.”

“Apparently. Someone from Zurich, Switzerland.”

“Switzerland?” He uncrossed his arms and stepped forward at last. “Really? You have friends in Switzerland?”

“Not that I can remember.” I was trying to read the original name, beneath my mother’s black scribble. V something something. “What do you think that is?”

“It’s not Vivian?”

“No, it ends with a t.”

An instant’s reflection. “Violet? Someone had your name wrong, I guess.”

For a man who’d just walked coatless through the dregs of an October rain, Doctor Paul was awfully warm. I wore a cashmere turtleneck sweater over my torso, ever so snug, and still I could feel the rampant excess wafting from his skin, an unconscionable waste of thermal energy. Up close, he smelled like a hospital, which bothered me not at all.

I sashayed to the kitchen drawer and withdrew a knife.

“Ah, now the truth comes out. Make it quick.”

“Silly.” I waved the knife in a friendly manner. “It’s just that I don’t have any scissors.”

“Scissors! You really are a professional.”

“Stand aside, if you will.” I examined the parcel before me. Every seam was sealed by multiple layers of Scotch tape, as if the contents were either alive or radioactive, or both. “I don’t know where to start.”

“You know, I am a trained surgeon.”

“So you say.” I sliced along one seam, and another. Rather expertly, if you must know; but then I had done the honors of the table at college since my sophomore year. Nobody at Bryn Mawr carved up a noble loin like Vivian Schuyler.

The paper shell gave way, and then the box itself. I stood on a chair and dug through the packing paper.

“Steady, there.” Doctor Paul’s helpful hands closed on the back of the chair, and it ceased its rickety-rocking obediently.

“It’s leather,” I said, from inside the box. “Leather and quite heavy.”

“Do you need any help? A flashlight? Map?”

“No, I’ve got it. Here we are. Head, shoulders, placenta.”

“Boy or girl?”

“Neither.” I grasped with both hands and yanked, propelling myself conveniently backward into Doctor Paul’s alert arms. We tumbled pleasantly, if rather ungracefully, to the disreputable rug. “It’s a suitcase.”

I CALLED my mother first. “What is this suitcase you sent me?”

“This is not how ladies greet one another on the telephone, darling.”

“Each other, not one another. One another means three or more people. Chicago Manual of Style, chapter eight, verse eleven.”

A merry clink of ice cubes against glass. “You’re so droll, darling. Is that what you do at your magazine every day?”

“Tell me about the suitcase.”

“I don’t know about any suitcase.”

“You sent me a package.”

“Did I?” Another clink, prolonged, as of swirling. “Oh, that’s right. It arrived last week.”

“And you had no idea what was inside?”

“Not the faintest curiosity.”

“Who’s it from?”

“From whom, darling.” Oh, the ring of triumph.

“From whom is the package, Mums?”

“I haven’t the faintest idea.”

“Do you know anybody in Zurich, Switzerland?”

“Nobody to you. Vivian, I’m dreadfully bored by this conversation. Can’t you simply open the damned thing and find out yourself?”

“I already told you. It’s a suitcase. It was sent to Miss Violet Schuyler on Fifth Avenue from somebody in Zurich, Switzerland. If it’s not mine—”

“It is yours. I don’t know any Violet Schuyler.”

“Violet is not nearly the same as Vivian. Doctor Paul agrees with me. There’s been a mistake.”

A gratifying pause, as Mums was set back on her vodka-drenched heels. “Who is Doctor Paul?”

I swiveled and fastened my eyes on the good doctor. He was leaning against the wall next to the window, smiling at the corner of his mouth, blue scrubs revealed as charmingly rumpled now that the full force of sunlight was upon them. “Oh, just the doctor I met in the post office. The one who carried the parcel back for me.”

“You met a doctor at the post office, Vivian?” As she might say, the gay bathhouse on Bleecker Street.

I leaned my hip against the table, right next to the battered brown valise, trusting the whole works wouldn’t give way beneath me. I was wearing slacks, unbelted, as befitted a dull Saturday morning, but Doctor Paul deserved to know that my waist-to-hip ratio wasn’t all that bad, really. I couldn’t have said that his expression changed, except that I imagined his eyes took on a deeper shade of blue. I treated him to a slow wink and wound the telephone cord around my fingers. “Oh, you’d adore Doctor Paul, Mums. He’s a surgeon, very handsome, taller than me, seems to have all his teeth. Perfectly eligible, really, unless he’s married.” I put the phone to my shoulder. “Doctor Paul, are you married?”

“Not yet.”

Phone back to ear. “Nope, not married, or so he claims. He’s your dream come true, Mums.”

“He’s not standing right there, is he?”

“Oh, but he is. Would you like to speak to Mums, Doctor Paul?”

He grinned, straightened from the wall, and held out his hand.

“Oh, Vivian, no …” But her last words escaped me as I placed the receiver in Doctor Paul’s palm. His palm: wide, firm, lightly lined. I liked it already.

“Good afternoon, Mrs. Schuyler … Yes, she’s behaving herself … Yes, I carried the parcel all the way up those wretched stairs. That’s the sort of gentleman I am, Mrs. Schuyler.” He returned my wink. “As a matter of fact, I do think there’s been some mistake. Are you certain there’s no one named Violet in your family? … Quite certain? … Well, I am a doctor, Mrs. Schuyler. I’m accustomed to making a diagnosis based on the symptoms presented by the subject.” A hint of a blush began to climb up his neck. “Hard to say, Mrs. Schuyler, but—”

I snatched the receiver back. “That will be enough of that, Mums. I won’t have you embarrassing my Doctor Paul with your remarks. He isn’t used to them.”

“He is a dream, Vivian. My hat’s off to you.” Clink, clink, rattle. The glass must be almost empty. “Try not to sleep with him right away, will you? It scares them off.”

“You would know, Mums.”

A deep sigh. Swallowed by the familiar crash of empty vodka glass on bedside table. “You’re coming for lunch tomorrow, aren’t you?”

“Not if I can help it.”

“Good. We’ll see you at twelve sharp.” Click.

I set the receiver in the cradle. “Well, that’s Mums. I thought I should warn you from the get-go.”

“Duly warned.”

“But not scared?”

“Not a lick.”

I tapped my fingernails against the telephone. “You’re certain there’s a Violet Schuyler somewhere in this mess?”

“Well, no. Not absolutely certain. But the fact is, it’s not your suitcase, is it?”

I cast the old gaze suitcase-ward and shuddered. “Heavens, no.”

“A cousin, maybe? On your father’s side? Lost her suitcase in Switzerland?”

“You mean a century or so ago?”

“Stranger things have happened.”

I set the telephone down on the table and fingered the tarnished brass clasp of my acquisition. As ancient as my mother’s virtue, that valise, and just as lost to history: cracked and dusty, bent in all the wrong places. A faint scent of musty leather crept up from its creases. There was no label of any kind.

I don’t mean to shock you, but I’ve never considered myself an especially shy person, now or then. And yet I couldn’t quite bring myself to undo that clasp and open the suitcase in the middle of my ramshackle Greenwich Village fifth-floor apartment. There was something odd and sacred about it, something inviolable in all that mustiness. (Quite unlike my mother’s virtue, in that respect.)

My hand fell away. I looked back at the telephone. “I think it’s time to call Great-aunt Julie.”

“VIOLET SCHUYLER, DID YOU SAY?”

“Yes, Aunt Julie. Violet Schuyler. Does she exist? Do you know her?”

“Well, well.” The line went quiet. I imagined her pacing to the limit of the telephone cord, like a horse on a gilded Park Avenue picket line. I imagined her pristine sixty-two-year-old face, her well-preserved brow making the ultimate sacrifice to this unexpected Saturday-morning conundrum.

“Aunt Julie? Are you there?”

“You’re certain the name was Violet? Foreign handwriting can be so atrocious.”

“It’s definitely Violet. Doctor Paul concurs.”

“Who’s Doctor Paul?”

“We’ll get to him later. Let’s talk about Violet. Obviously you know the name.”

She exhaled with drama, as if collapsing on the sofa. I heard the scratching of her cigarette lighter. Must be serious, then.

“Yes, I know the name.”

“And?”

A long breath against the mouth of the receiver. “Darling, she was my sister. My older sister, Violet. A scientist. She murdered her husband in Berlin in 1914 and ran off with her lover, and nobody’s heard from her since.”

Violet, 1914 (#ulink_e20551f5-87e3-52da-b114-e69816e74c0a)

BERLIN (#ulink_e20551f5-87e3-52da-b114-e69816e74c0a)

The Englishman walks through the door of Violet’s life in the middle of an ordinary May afternoon, smelling of leather and outdoors.

She’s not expecting him. In that hour, Berlin is crowded with light, incandescent with sunshine and possibility, but Violet has banished brightness within the thick redbrick walls of her basement laboratory. She closes the door and lowers herself into a wooden chair in the center of the room, where she stares without moving at the heavy blackness surrounding her.

In her blindness, Violet’s other senses rise up with primeval sharpness. She counts the careful beats of her heart, sixty-two to the minute; she hears the click of footsteps down the linoleum hallway outside her room. The sterile scents of the laboratory fill her nostrils: cleaning solutions and chemicals, paper and pencil lead. Deeper still, she feels the weight of the furniture around her, interrupting the empty space. The chairs, the table, the radioactive apparatus she is about to employ. The door in the corner, from which she can just begin to detect a few thin lines of light stealing past the cracks.

As she sits and waits, as her pupils dilate by tiny fractions of degrees, the stolen light from the doorway finds the walls and the furniture, and the intricate charcoal shadow of the apparatus atop the table. Violet removes a watch from her pocket and consults the luminous dial. She has been sitting in her shapeless void for ten minutes.

Ten more minutes left.

Violet replaces her watch and resists the urge to rise and check the apparatus. She set it up with her own hands; she has already inspected each detail; she has already performed this experiment countless times. What possible surprise could it hold?

But a trace of unease seems to have stolen into the room with the light from outside the door. It pierces Violet’s calm preparation and winds around her chest like the thread behind a needle. She counts her pulse again: sixty-nine beats to the minute.

What an extraordinary anomaly.

She has never experienced this sensation before an experiment. Her nerves are cool and precise; her nerves are the very reason she was first delegated to perform this particular duty. She might go further and say that her nerves had brought her to this point in her life: her work, her unconventional marriage, her existence here in Berlin in this incandescent May of 1914, in a basement laboratory at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institut, waiting for her pupils to dilate to the necessary degree before she can begin an experiment at the frontier of atomic physics.

But she can’t deny the existence of this sensation that tightens about her heart. It is real, and it is quantifiable: seven additional beats of her heart in every minute.

A double knock strikes the door.

“Come in,” Violet says.

She closes her eyes as the door opens, because she doesn’t want the additional light to interrupt the adjustment of her pupils. Footsteps beat against the linoleum; the door clicks shut. Her husband, probably, come to check on her progress. To stand over her and ensure that she gets nothing wrong. That she misses nothing.

But in the split second before he speaks, Violet knows this intruder isn’t her husband. These footsteps are too heavy, the leathery air that whirls through the door with him too brash. Her senses recognize his strangeness just before his voice confirms it.

“I hope I’m not disturbing you, Mrs. Grant.”

Violet opens her eyes.

“My name is Richardson, Lionel Richardson. Your husband told me you wouldn’t mind my observing the experiment.”

Your husband told me. Walter sent this stranger to her?

Again, that unsettling sensation in her chest. If only she could see him. His black shape outlines the blacker void around him, obstructing the light from the door without a trace. His voice rumbles from the center of a capacious chest, low and respectful, the syllables clipped by precise British scissors.

I hope I’m not disturbing you.

“Not at all,” Violet says crisply. “Are you a colleague of his?”

“No, no. A former student.” He makes some movement in the darkness, indicating the apparatus. “Used to do these sorts of things myself.”

“Then I need not apologize for the darkness. Would you like to sit?” Her heart is beating even faster now, perhaps seventy-five hard strikes a minute. It must be surprise, that’s all. She’s rarely interrupted in those experiments, which are long and repetitious and generally unworthy of spectators. Her animal brain is simply reacting to the sudden presence of an unknown organism, a possible threat. An unexpected foreign invader who might be anyone or anything, but whose vital and leathery bulk doesn’t belong in the quiet darkness of her laboratory.

“Thank you.” A chair scrapes against the linoleum, as if Lionel Richardson can see in the dark. Or perhaps he simply memorized the location of the furniture in the brief flash of light at his entrance. “Are you nearly ready to begin, Mrs. Grant?”

“Almost.” Violet consults her watch again. “Another three minutes.”

Richardson laughs softly. “I remember it well. No twenty minutes ever passed so strangely. Time seems to stretch out, doesn’t it? A sort of black infinity, disconnected from everything else. All sorts of profound thoughts would pass through one’s brain. Not that I could ever recall them afterward.”

Yes, Violet thinks. That’s it exactly. “You’re here for old times’ sake, then?”

Another laugh. “Something like that. Dr. Grant told me someone else was performing my old duties this very minute, and I couldn’t resist a peek. Do you mind?”

“Not at all.”

Of course she minds. Lionel Richardson seems to take up half the room, as if he’s swallowed up the blackness to leave only his own solid limbs, his broad and rumbling chest. Violet is seized with a burst of annoyance at her husband, who surely should have known better than to send this stranger to swallow up her laboratory while she sits waiting in the darkness, alone and unsuspecting.

Richardson says, “I’d be happy to help you with the counting. I know it’s something of an eyestrain.”

“That’s not necessary. It takes some practice, as you know.”

“Oh, I remember how. I was the first one, you know, back in ought-nine, when your husband began his experiments. I still see those bloody little exploding lights, sometimes, when I close my eyes.”

Violet laughs. “I know what you mean.”

“Maddening, isn’t it? But I see the crafty doctor has found a permanent replacement for me. A far more agreeable one, at any rate.”

This time Violet feels the actual course of acceleration in her chest, the physical sense of quickening. How did one bring one’s heart back under proper regulation after a shock? You couldn’t simply order it to slow down. You couldn’t simply say, in a firm voice, as one spoke to a misbehaving child: Sixty-two beats is more than sufficient, thank you. The heart, an organ of instinct rather than reason, had to perceive that there was nothing to fear. The chemical signals of danger, of distress, had to disperse from the blood.

Violet flicks open her watch. “It’s time. Are you able to see?”

“Just barely.”

“We can wait a few more minutes, if you like.”

“No, no. I’m not here to interrupt your progress. Carry on.”

Violet rises from her chair and moves to the table in the center of the room, guided more by feel than by sight. She flicks the switch on the lamp, though she doesn’t look directly at the feeble low-wattage bulb. It illuminates her notepad and pencil just enough that she can write down her notes.

She casts her eyes over the apparatus: the small box at one end, containing a minute speck of radium; the aperture on the box’s side, through which the particles of radiation shoot unseen toward the sheet of gold foil; the glass screen, coated with zinc sulfide; and the eyepiece with its magnifying lenses.

She takes out her watch, settles her right eye on the eyepiece, and squints her left lid shut.

A tiny green-white flash explodes in her vision, a delicate firework of breath-stopping beauty. But Violet’s breath is already stopped, already shocked by the unexpected invasion of Lionel Richardson into her laboratory, and the tiny flashes make no impression, other than the scratches of her pencil as she counts them.

Why this oversized reaction? Why this perception of imminent danger?

Has Walter perhaps mentioned Lionel Richardson’s name before? Is there some association buried in her subconscious that causes the synapses of her brain to crackle with electricity, to issue these messages of alarm down her neural pathways to the muscles of her heart and lungs? Or maybe it’s just that she can’t see him, can’t inspect his face and clothes and person and confirm that he’s speaking the truth, that he’s only a man, a visiting former student of her husband’s, benignly curious.

Violet takes her eyes from the screen for an instant to check her watch. Nearly five minutes have passed. At five minutes she will draw a line under her counting marks and start again.

“Can I help you? Keep time for you?” asks the invader.

“It’s not necessary.” She looks at her watch. Five minutes. She draws a line.

“Aren’t you missing your count, looking back and forth like that?”

“A few, of course.”

“Dr. Grant always had me take a partner to keep time. We switched off to rest our eyes.” He offers this information respectfully, without a trace of the usual scientific arrogance.

“We don’t have the staff for that here in Berlin.”

“You have it now.”

Without taking her eye from the eyepiece, Violet grasps the watch in her left hand and holds it out. “Very well. If you insist.”

He gathers the watch in a light brush of his fingers against her palm. “Five-minute intervals?”

“Yes.” Violet shuts her eyes.

“All right. Ready …”

A tranquil leather-scented silence warms the air. Violet breathes it deeply inside her, once, twice.

“Go.”

Violet opens her eyes to the glorious flashing blackness, the stars exploding in her own minute universe. Her pencil moves on the paper, counting, counting. Lionel Richardson sits just behind her, unmoving, close enough that she can feel the heat radiating from his body. He holds her watch in his steady palm. Her gold pocket watch, unadorned, almost masculine; the watch her sister Christina gave her four years ago on a smoke-drenched pier on the Hudson River, as the massive transatlantic liner Olympic strained against her moorings a few feet away. Her watch: Violet’s only parting gift from the disapproving Schuylers.

“Time,” says Lionel Richardson.

Violet draws a line to begin a new count.

“And … go.”

He issues the direction with low-pitched assurance, from his invisible post at her left shoulder. He hasn’t simply swallowed the blackness, he’s become the dark space itself. Even his scent has absorbed into the air. Violet makes her tireless marks on the notepad. She sinks into the world of electric green-white scintillations, the regular strikes of radioactive particles against atomic nuclei, and somewhere in the rhythmic beauty, her heart returns at last to its usual serene pace, her nerves smooth down their ragged edges. Only the pencil, hard and sharp between her thumb and forefinger, links her to the ordinary world.

“Time,” says Richardson, and then: “Would you like me to count this round? Your eyes must be aching.”

Her eyes are aching. Her shoulders ache, too, and the small of her back. She straightens herself. “Yes, thank you.”

Lionel’s chair scrapes lightly. His body slides upward in the darkness behind her. A pressure cups her right elbow: his hand, guiding her around her own chair and into his. He places the watch in her palm and settles into the seat before the eyepiece, hunching himself around the apparatus without complaint, for he’s much larger than she is.

She lifts the watch and stares at the face. “Ready?”

“A moment.” He adjusts himself, settles his eye back against the lint lining. His profile, lit by the dim bulb next to the notepad, reveals itself at last: firm and regular, the nose a trifle large, the hair short and dark as ink above his white collar. His forehead is high, overhanging the eyepiece, and in the soft yellow light Violet cannot detect a single line. “Ready.”

She drops her gaze back to Christina’s watch.

“And … go.”

Vivian (#ulink_1c88edb9-4a40-5c02-8b67-26bb1b1289c4)

Aunt Violet. I had a great-aunt named Violet, an adulteress and murderess, about whom I’d never heard. A scientist. What sort of scientist?

I regarded the valise on my table, and then turned to tell Doctor Paul the extraordinary news.

Alas. Too late.

Inexplicably, unfathomably, he lay upon my sofa, in the hollow left by Sally’s debauched corpse an hour or two earlier, so profoundly asleep I was tempted to hold my compact mirror to his mouth and check for signs of life.

Hands to hips. “Well. There’s courtship for you.”

But then a tiny steel ball bearing of sentiment rolled downward through the chambers of my heart. Poor dear Doctor Paul. One arm crossed atop his chest; the other dangled to the floor. His legs, far too long for the sweeping red Victorian curves of the sofa, propped themselves over the edge of the opposite armrest.

I knelt next to him and touched the lock of hair that drooped in exhaustion to his forehead. Up close, I could see the tiny lines that fanned from the outer corners of his eyes. I bent my nose to his neck. Here, he smelled of salt instead of antiseptic, and perhaps a little long-forgotten soap, too, sweet and damp. I rubbed the tiny golden bristles of his nascent beard with my pinkie. He didn’t even flinch.

“Aren’t you just too much,” I whispered.

AUNT JULIE blew into the apartment half an hour later, smelling of cigarettes and Max Factor pancake foundation. She flung her hat on the stand but kept her coat in place. When you maintained a figure like hers so far past its biblically ordained two score and ten, you lived in a perpetual state of Pleistocene chill.

“Where is this suitcase of yours?” she demanded, lighting a cigarette.

“It’s not mine. That’s the point. Drink?” I didn’t wait for an answer. The liquor filled a cabinet of honor in the kitchen—such as it was—and while Aunt Julie might not admire the quality of the refreshment provided, she had to approve of its quantity.

She whipped off her gloves just in time to accept her Bloody Mary, no celery. “Haven’t you opened it yet?”

“Of course not. It’s not mine.”

“For God’s sake, my dear. Did your mother raise you with no standards at all?” She drained down half a glass, set the tumbler on the table, and put her hand on the valise’s tarnished brass clasp. “Well, well.”

“Now, wait just a minute.” I darted over and snatched her hand away.

“What are you doing?”

“I don’t think we have any right to look inside.”

“Darling, she’ll never know.”

“How do we know that?”

“Nobody’s heard from her for fifty years. I’d say that was a pretty decent indication, wouldn’t you?”

“We should make some sort of effort to track her down first.”

Aunt Julie rolled her eyes and picked up her pick-me-up. “Ah, that’s good. You’re the only one of my nieces and nephews to mix a decent drink.”

“I had the finest instruction available.”

She wagged a finger. “Teach a girl to fish—”

“Look, Aunt Julie, about this Violet of yours …”

But Aunt Julie had already turned, aiming for the kitchen and a refill, and stopped with a rattle of dying ice. “Vivian, my dear,” she said slowly, “there’s a man on your sofa.”

“You don’t approve?”

“Oh, I approve wholeheartedly. But I do feel compelled to ask, for form’s sake, where the hell you picked him up on such short notice, and why he isn’t dressed more suitably.”

I came up behind her and slipped my arm about her waist. “Isn’t he a dream? I found him at the post office.”

“Delivered and signed for?”

“Mmm. Poor thing, he works such long shifts at the hospital. He carried up the package for me with his last dying surge of energy, and then he just”—I waved my hand helplessly—“collapsed.”

“Imagine that. What do you plan to do with him?”

“What do you suggest?”

She resumed her journey to the liquor cabinet. “Just don’t sleep with him right away. It scares them off.”

“Funny, Mums already warned me. Tell me about Violet.”

“There isn’t much to tell. Not much that I know, anyway. I was the baby of the family. I was only nine years old when she left for England. That was 1911, I believe.” Aunt Julie wandered back from the kitchen and leaned against the table, drink in hand, staring lovingly at Doctor Paul.

“Why did she leave for England? Was she sent away?”

“No, the opposite. She wanted to be a scientist, and naturally that didn’t go down well in Schuylerville. I remember the most awful rows. They let her go eventually, I suppose—there’s not much you can do with a girl if she’s got her heart set on something—and washed their hands of it.” Aunt Julie cocked her head. “What color are his eyes?”

“Blue. Exactly the same shade as his scrubs. And stop trying to distract me.”

“I’ve changed my mind. Get him in bed pronto.”

“You know, I’ll bet he can hear you in his subconscious.”

“I hope he does. You could use a good love affair, Vivian. It’s the one thing you’re missing.”

I wagged my finger. “You’re the most miserable excuse for a chaperone in the history of maiden aunts.”

“I am not a maiden aunt. I’ve been married several times.”

“Regardless, I’m not going to sleep with him. Look at the poor darling. He’s exhausted.”

“I find,” said Aunt Julie, swishing her gin, “they can generally summon the energy.”

I crossed the floor to my bedroom—it didn’t take long—and took the extra blanket from the shelf. I called back: “Now talk. What did Violet do in England?”

“Got married to her professor, like the sane girl she was. She was very pretty, Violet, I’ll say that, though she didn’t care about anything except her damned atoms and molecules.”

I returned and spread the blanket over Doctor Paul, taking extra care with his doughty shoulders. “But then she murdered him.”

“Well, I don’t know the details of all that. The family hasn’t spoken of it since, never even uttered her name. I don’t think there was a trial or anything like that. But yes, the fellow was murdered, and Violet ran off with her lover. From a suite at the Adlon, of course. She did have taste.” She snapped her fingers. “And poof! That was that.”

“There must be more to it.”

“Of course there’s more.”

“And you were never curious?”

“I was young, Vivian. I hardly knew her, really. She was at school, and then she was in England.” Aunt Julie set her glass on the table and crossed her arms. “I wondered, of course. Once or twice, when I was in Europe, I asked a few questions. But nothing ever turned up.”

She was staring at the valise now, her lips turned down in a crimson crescent moon. She stretched out one claw and touched the lonely leather.

“I don’t believe you,” I said.

“Of course you don’t. You’re young and suspicious.”

“And I know you, Aunt Julie.” I pointed at her duplicitous chest. “Out with it.”

She spread her hands. “I’ve told you all I know.”

She played her part well. Round eyes, innocent eyebrows. Mouth set irrevocably shut. I crossed my arms and tapped an arpeggio into my left elbow. “I can’t believe I had another great-aunt, all these years, and nobody ever mentioned it.”

Aunt offered me with a pitiful smile. “We’re the Schuylers, darling. Nobody ever would.”

From the window over the back courtyard came the sound of crockery smashing. A baby wailed. My first night in the apartment, with the roommate I’d met only that morning, I hadn’t slept a wink: the cramped squalor was so foreign to Fifth Avenue, to Bryn Mawr, to the rarefied quiet of a Long Island summer. I adored every piece of makeshift purloined furniture, every broken cabinet door held together with twine, every sound that shrieked through the window glass and told me I was alive, alive.

“Let’s open the valise,” said Aunt Julie. “I want to see what’s inside.”

“God, no. What if it’s a skeleton? Her dead husband?”

“All the better.”

I shook my head. “I can’t open it. Not until I know if she’s still alive.”

“You sound like a melodrama. If you really want the truth, it’s inside that bag.” She stabbed it with her finger. “That’s where you’ll find Violet.”

“Well, it’s locked,” I said. “And there’s no key.”

Doctor Paul stirred on the sofa. “Clamp, not screw,” he muttered, and turned his face into the cushion.

I dropped my voice to a whisper. “See what you’ve done! Now, be quiet. He needs his sleep.”

Nobody could invest a standard-issue eye roll with as much withering contempt as Aunt Julie. She did it now, right before she marched to the hat stand and lifted her hat—a droll little orange felt number, perfectly matching her orange wool coat—from its hook. Crimson lips, orange hat: only Aunt Julie could pull that one off.

I followed her and placed a kiss on her cheek. “Stay dry.”

She shook her head. “You won’t break open the mysterious suitcase sitting on your own kitchen table. You won’t go to bed with that adorable doctor sleeping on your sofa.”

I opened the door for her and stood back.

Aunt Julie thrust her hat pin just so and swept into the vomit-stained hallway. She called, over her shoulder: “Youth is wasted on the young.”

EONS PASSED before the scent of Aunt Julie’s Max Factor faded from the air. I spent them tidying up the apartment—as far as feeble human ability could achieve, at any rate—and generally hiding all evidence of sin.

I did this not to favorably impress Doctor Paul when he woke (at least, not exclusively) nor out of a general desire for cleanliness (of which I had little) but because I liked to keep my hands busy while my brain wrestled with a problem.

And my new aunt Violet was a doozy of a problem.

A woman scientist: now, that was interesting, something I could understand. Not that I liked the sciences particularly, but I could see her struggle as vividly as I saw mine, for all the half century of so-called progress between us. Not only was this Violet a female scientist, poor dear. She was also a scientific female. She would have sat at the lonely table, wherever she made her home. I couldn’t blame her for marrying her professor.

The question was why she killed him afterward.

My housemaidenly urgings flickered and died. I sank into the chair at the table, feather duster in hand, and touched my finger, as Aunt Julie had, to the sturdy leather. That’s where you’ll find Violet, Aunt Julie had said, but it seemed to me that she existed elsewhere. That the marks and stains of her life’s work lay scattered out there, in the wide world, and that the contents of this particular valise were instead private, the detritus of her soul. I had no right to them. What if someone opened up my suitcase?

In the wake of the earlier fracas, the courtyard had gone unnaturally still. The clock ticked mechanically in my ear, and for some reason the sound reminded me that I hadn’t had lunch, that I had packed an entire week’s worth of excitement into a single Saturday afternoon, and for all I knew it might be dinnertime already.

I glanced at the face. Two-thirty-one.

I rose from the table and went to the kitchen, where I measured water and coffee grounds into the percolator. Doctor Paul would need coffee when he woke up, and lots of it.

Two-thirty-one. I’d known the good doctor for two hours and thirty-nine minutes, and he’d been asleep for most of it. I plugged the percolator into the wall socket and opened the refrigerator. Butter, cheese. There must be some bread in the breadbox.

Doctor Paul would be hungry, too.

AH, the scent of brewing coffee. It bolts a man from peaceful slumber faster than the words Darling, I’m pregnant.

I watched his big blue eyes blink awake. I savored the astonished little jerk of his big blue body. “Hello, Doctor,” I said. “Welcome to heaven.”

He looked at me, and his head relaxed against the pillow. “You again.”

“I made you grilled cheese and tomato soup. And coffee.”

“You didn’t.”

“You carried my parcel. It was the least I could do.”

He smiled and sat up, all blinky and tousley and shaky-heady. “I don’t know how I fell asleep.”

“It seems pretty straightforward to me. You were exhausted. You made the mistake of lowering your poor overworked backside onto my unconscionably comfortable sofa. Voilà. Have some coffee.”

He accepted the cup and took a sip. Eyelids down. “I think I’m in love with you.”

“Aw, you big lug. Wait until you taste my grilled cheese.”

Another sip. “I’d love to taste your grilled cheese.”

Well, well.

I rose to my feet and went to the kitchen, where Doctor Paul’s sandwich sat in the oven, keeping warm. When I returned, his eyes lifted hopefully.

I handed him the plate. “So tell me about yourself, Doctor Paul.”

“I do have a last name, if you’d care to hear it.”

“But, Doctor, we hardly know each other. I’m not sure I’m ready to be on a last-name basis with you.”

“It’s Salisbury. Paul Salisbury.”

“You’ll always be Doctor Paul to me. Now eat your sandwich like a good boy.”

He smiled and tore away a bite. I perched myself at the edge of the armchair, such as it was, and watched him eat. I was still wearing my frilly white apron, and I smoothed it down my front like any old housewife. “Well?”

“I do believe this is the best grilled cheese I’ve ever had.”

“It’s my specialty.”

He nodded at the suitcase. “Haven’t you opened it yet?”

“Oh, that. You’ll never guess. It belonged to my secret great-aunt Violet, who murdered her husband and ran off with her lover, and the damned thing is, of course, locked tight as an oyster with a lovely fat pearl inside.”

Doctor Paul’s sandwich paused at his mouth. “You’re serious?”

“In this case, I am.”

He enclosed a ruminative mouthful of grilled cheese. “I hope you don’t mind my asking whether this sort of behavior runs in the family?”

“My behavior, or hers?”

“Both.”

I settled back in my armchair and twiddled my thoughtful thumbs. “Well. I can’t say the Schuylers are the most virtuous of human beings, though we do put on a good show for outsiders. Still and all, outright psychopathy is generally frowned upon.”

“I can’t tell you how relieved I am to hear it.”

“That being said, and as a general note of caution, psychopaths do make the best liars.” I clapped my hands. “But enough about little old me! Let’s turn our attention to the alluring Dr. Paul Salisbury, his life and career, and, most important, when he’s due back at his hospital.”

Doctor Paul set his empty plate on the sofa cushion next to him, rested his elbows on his knees, and leaned forward. His eyes took on that darker shade again, or maybe it was the sudden rush of blood to my head, distorting my vision. “Midnight.”

I lost my breath.

“I’m supposed to be sleeping right now. I was supposed to return to the hospital from the post office, change clothes, and go back to my apartment to sleep.”

“Where’s your apartment?”

“Upper East Side.”

“My condolences.”

“Thanks. I should have found a place closer to the hospital.”

I looked at the clock. “You’ve lost hours already.”

“I wouldn’t say that.”

I untangled my legs and rose to fetch the tomato soup. “I hope you don’t mind the mug. We don’t seem to have any bowls yet.”

“Whatever you have is fine.” He took the mug with a smile of thanks. Oh, the smile of him, as wide and trusting as if the world were empty of sin. “Wonderful, in fact. Sit here.” He whisked away the plate and patted the sofa cushion next to him.

I settled deep. I was a tall girl—an unlucky soul or two might have said coltish in my impulsive adolescence—and I liked the unfamiliar way his thigh dwarfed mine. The size of his knee. I studied those knees, caught the movement of his elbow as he spooned tomato soup into his mouth. The patient clinks of metal against ceramic said it all: anticipation, discovery, certainty. The real deal, something whispered in my head.

When he had put himself on the outside of his tomato soup, Doctor Paul cupped the empty mug in his palms. “What would you like to do now, Vivian?”

“I was hoping you’d say that. Did you have anything particular in mind, Doctor, dear?”

“I was asking you.”

“Well, Mother said I shouldn’t go to bed with you right away. It would scare you off.”

I couldn’t see for certain, but I’ll bet my best lipstick he blushed. If I closed my eyes, I could feel the warmth on my nearby cheek.

“Aunt Julie concurred,” I added. “At first, anyway. Until she got a good look at you.”

“I’m not saying they’re right,” he said carefully, “but there’s no rush, is there?”

“You tell me.”

“No. There’s no rush.”

We sat there, side by side, legs not quite touching. Doctor Paul rotated the mug in his hands, his competent surgeon’s hands. They looked older and wiser than the rest of him. He kept his nails trimmed short, his cuticles tidy. The tiny crescents at the base were extraordinarily white.

He cleared his throat. “Of course, I didn’t mean to imply that I’m not tempted. Just to be clear. Extremely tempted.”

“Mind over matter?”

“Exactly.”

“I’d hate to lead you astray from the well-worn path of virtue.”

He cleared his throat again. Blushed again, too, the love. If he kept giving off that kind of thermodynamic spondulics, I was going to have to change into something less comfortable. “Yes, of course,” he mumbled.

I lifted my eyes, and the table appeared before me, and my great-aunt Violet’s suitcase atop it. Aunt Violet, who ran away with her lover into the Berlin summer. Had they made it to Switzerland together? She would be in her seventies now, if she were still alive. If she had succeeded.

Doctor Paul rose from the sofa in a sudden heave of dilapidated upholstery. His hand stretched toward me, palm upward, open and strong. “Let’s go somewhere, Vivian.”

“What about your sleep?”

“I’ll catch up eventually. This is more important.”

I took his hand and let him pull me upward. “If you must. Where do we go?”

He stood close as a whisker, solid as a deep-blue tree. “How about the library?”

“The library.”

“Yes, the library.” Doctor Paul reached around my back, untied my frilly apron, and lifted it over my head. “We’re going to find out all about this aunt of yours.”

Violet (#ulink_b0bae944-d960-538c-9d97-100f606c3cf0)

Your husband told me you wouldn’t mind, Lionel Richardson said. For the life of her, Violet can’t imagine why. In the course of their two and a half years together, Walter has only allowed one other man inside the darkened laboratory with her: namely, himself.

But then, like most illicit affairs, theirs was unequal from the beginning. Violet’s youth, her loneliness, her awe-swollen gratitude were no match for Dr. Grant’s experience. At nineteen—at any age—innocence doesn’t know its own power. To know that power, after all, is to lose it.

In Violet’s downcast moments—now, for example, as she locks the laboratory door and trudges in the direction of Lionel Richardson’s laughter down the hall—she forces herself to recall the instant of their meeting, the instant in which everything changed. When the chains of her attachment were first forged.

She climbs the stairs to her husband’s office, from which Richardson’s laughter originates, but she sees instead the familiar Oxford room of 1911, richly appointed, and the angular man standing in the doorway before it: the legendary Dr. Walter Grant made manifestly physical. She remembers how every aspect exuded masculine eminence, from his thin-lipped mouth surrounded by its salty trim beard to his graying hair gleaming with pomade under the masterful glow of a multitude of electric lamps. He wasn’t a large man, but neither was he small. He was built like a whip, slender and hard, and the expert tailoring of his clothes to his body gave him an additional substance that, in Violet’s eyes, he didn’t require.

At the moment of that first meeting, Violet was somewhat out of breath. She had grown agitated, speaking to his private secretary, whose job it was to protect the great man from unforeseen attacks like hers; she was also hot beneath her drab brown clothes, because it was the end of August and the heat lounged about the yellowed university stones, an old beast exhausted by the long summer and refusing to be moved. Damp with perspiration, her chest moving rapidly, Violet pushed back her loosened hair with firm fingers and announced herself.

Clearly, Dr. Grant was annoyed at the disturbance. He turned his grimace to the secretary.

“I’m dreadfully sorry, sir. The young lady will simply not be moved. Shall I call someone?” The secretary’s clipped gray voice betrayed not the slightest sense of Violet as a fellow female, as a fellow human being, as anything other than an obstacle to be removed from Dr. Grant’s eminent path.

Violet was used to this. She was used to the look of aggravation on Dr. Grant’s face. She was used to rooms like this, the smell of wooden furniture and ancient air, the acrid hint of chemicals in some distant laboratory, the clickety-click of someone’s typewriter interrupting the scholarly quiet. She tilted up her chin and held out her leather portfolio of papers. “With all respect, Dr. Grant, I will not leave until I learn why my application to your institute has once more been sent back, without any sign of its having been read and considered.”

“Application to this institute,” said the secretary scathingly. “The cheek of these American girls. I shall ring for help at once, Dr. Grant.” She lifted the receiver of a dusty black telephone box.

But Dr. Grant held up his hand. He looked at Violet, really looked, and his eyes were so genuinely and intensely blue that Violet felt a leap of childlike hope inside her ribs.

“What is your name, madame?” he asked.

“Violet Schuyler, sir. I have recently graduated with highest honors from Radcliffe College in Massachusetts, with bachelor of science degrees conferred in both mathematics and chemistry. My marks are impeccable, I have letters of recommendation from—”

“When did you first make your application to the institute?”

“In March, sir. It was returned in April. I presumed there had been some misdirection, so I sent it again, and—”

He turned to the secretary. “Why have I not seen Miss Schuyler’s application?”

The secretary knit her fingers together on the desk and creased her narrow eyes at Violet. “I assumed, sir, that—”

“That I would not consider an application from a female student?”

“Dr. Grant, the institute … that is, there is not a single scientist who … It’s impossible, sir. Of course it is. Your laboratory is no place …”

Dr. Grant turned back to Violet with eyes now livid. “I apologize, Miss Schuyler. Your application should have been received with exactly the same attention as any other. If you will please do me the honor of attending me in my office, I shall read it now, with the utmost regard for your tenacity in delivering it against all obstacles.” He stood back and motioned with his arm.

And so it began, the awakening of Violet’s gratitude, in that instant of triumph over the pinched and gray-suited secretary. She swept into Dr. Grant’s office and heard the firm click of the door as he closed it behind them, the decisive shutting-out of disapproving secretaries and rigid parents from the territory around them.

“Sit, I beg you,” he said, proffering a venerable old leather chair, and Violet sat. He pulled out his pair of rectangular reading glasses and settled into his own chair, behind the desk, while the clock drummed away in the corner and a robin sang from the tree outside the open window. As he read, he remained absolutely still, as if absorbed whole into the papers before him. Violet clenched her fingers around her knee and observed his purposeful energy, the fighting trim of his whip-thin body. Dr. Grant was three years older than her own father, and yet every detail of him belonged so clearly to a newer age, the modern age. Even his graying hair, the color of burnished steel.

How on earth did she get here, in this English building, filled with a race of people to whom she did not belong? Why had she fled her family, her life, her country, her comfortable future? What was she doing?

You’re greedy, her mother had said to her quietly, that last night in New York, as she had packed her things. Greedy and selfish. It’s not the knowledge you want, you can have that from your journals. You want to be in the newspapers, you want to be Marie Curie, you want to think you’re different from all of us. That all other women are silly and complacent and conventional, except you, brilliant you.

Isn’t that right, Violet?

“I beg your pardon,” Dr. Grant said, raising his head a quarter hour later to part the curtain of silence between them. “I believe a mistake has been made. You are quite the most qualified applicant to this institute in four years.”

Despite his heroic vanquishing of the secretary, Violet had somehow been expecting resistance. Resistance was all she knew: from her parents, filling the musty Fifth Avenue air with argument and expostulation; from her brothers, jeering over the silver and crystal. The opposition of the entire world against one embattled island of Violet.

She opened her mouth to return this volley that did not arrive. Instead, on the end of a wary breath, she offered: “I was informed at the outset that it’s too late to enter the university for the current term.”

He waved that aside in a flash of starched white cuff. “I shall see to it personally. You will have to join one of the women’s colleges, of course. Somerville, I think, will be best. I know the principal well; there should be no trouble at all. Have you lodgings?”

“I am at the Crown,” she said numbly.

He made a small black note on the paper before him. “I will see to it at once. A quiet, discreet pair of rooms. You have no companion, I take it?”

“No. I am independent.”

“Very good.”

Very good. Violet absorbed the note of rich satisfaction in his voice, above the glacial white of his collar, the symmetrical dark knot of his necktie. He was wearing a tweed jacket and matching waistcoat, and when he rose to bid her a tidy good afternoon, he unfastened the top button in an absent gesture to let the sides fall apart across his flat stomach.

Violet looked directly into his eyes, at that unsettlingly clear blue in his polished face, but her attention remained at his periphery, at that unfastened horn button, from which the tiny end of a thread dangled perhaps a quarter inch.

Now, as she pauses once more outside her husband’s office door, she remembers longing, quite irrationally and against her finest principles, to mend it for him.

Vivian (#ulink_7107193e-c989-5bb6-a8fb-b7405224f577)

By the time we reached Twenty-first Street, we were holding hands. I know, I know. I don’t consider myself the hand-holding kind of girl, either, but Doctor Paul reached for me when a checker cab screamed illegally around the corner of Fifth Avenue and Twentieth, against the light, and what would you have me do? Shrug the sweet man off?

So I let it stay.

Doctor Paul had suggested walking instead of the subway, once he emerged from the hospital locker room, shiny and soapy and shaven, hair damp, body encased in a light suit of sober gray wool with a dark blue sweater-vest underneath. I would have said yes to anything at that particular instant, so here we were, trudging up Fifth Avenue, linked hands swinging between us, sun fighting to emerge above our heads.

“You’re unexpectedly quiet,” he said.

“Just taking it all in. I suppose you’re used to bringing home blondes from the post office, but I’m all thumbs.”

He laughed. “I’ve never brought home a blonde from the post office, and I never will.”

“Promises, promises.”

“I happen to prefer brunettes.”

“Since when?”

“Since noon today.”

“And what did you prefer before that?”

“Hmm. The details are strangely hazy now.”

I gave his hand a thankful squeeze. “Stunned you with my cosmic ray gun, did I?”

He peered up at the sun. “I said to myself, Paul Salisbury, any girl who can say Holy Dick in the middle of a crowded post office in Greenwich Village, that girl is for keeps.”

“Nothing to do with my irresistible face, then? My tempting figure?”

“The thought never crossed my mind.”

I couldn’t see for the galloping unicorns. The Empire State Building lay somewhere ahead, over the rainbow. “The blue scrubs did it for me. I’ve had a doctor complex since I was thirteen. Just ask my shrink.”

“And to think my pops didn’t want me to go to medical school.”

I stopped in the middle of the sidewalk and turned to him. “You’re having me on, aren’t you?”

He shook his head.

“But everyone wants his son to be a doctor. No one brags about his son the banker, his son the lawyer.”

“Not mine.”

I squinted suspiciously. “Are you from earth?”

“I’m from California.”

I nodded with understanding and turned us back up the sidewalk. “Aha. That explains everything.”

“Everything?”

“Everything. The golden glow, the naive willingness to follow a strange girl upstairs to her squalid Village apartment. I knew you couldn’t be a native New Yorker.”

“As you are.”

“As I eminently am. Tell me about California. I’ve never been there.”

He told me about cliffs and beaches and the cold Pacific current, about his family’s house in the East Bay, about the fog that rolled in during the summer afternoons, you could almost set your watch by it, and the bright red-orange of the Golden Gate Bridge against the scrubbed blue sky. Did I know that they never stopped painting that bridge? By the time they had finished the last stroke, they had to start all over again from the beginning. We were just escaping from Alcatraz when the stone lions of the New York Public Library clawed up before us.

“After you,” said Doctor Paul.

“SO. I suppose we should start with Violet Schuyler,” said Doctor Paul, in his best hushed library whisper.

“How you joke.”

“No?”

“My dear boy, don’t you know? It’s much easier to find out about men. Even if my aunt Violet were the most talented scientist in the Western world, she would probably only rate a small paragraph in the E.B. Either no one would have paid her any attention, or some man would have jumped in to take credit for her work.”

“Really?” The old lifting eyebrow.

“Really.”

“What about Marie Curie?’

“The exception that proves the rule. And she worked with her husband.”

“All right, then. So what was Violet’s husband’s name?”

“That I don’t know.”

“Shh,” said the librarian.

The New York Times came to our rescue. “She’s a Schuyler,” I told Doctor Paul. “Even if the family disowned her, they’d still have put a wedding announcement in the paper.”

He shook his head. “And they say Californians are the loonies.”