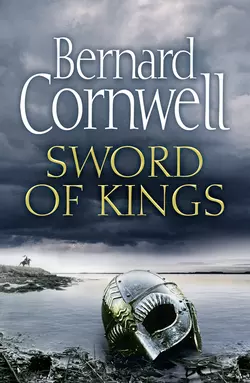

Sword of Kings

Bernard Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 2049.57 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The 12th book in the epic and bestselling series that has gripped millions. A hero will be forged from this broken land. As seen on Netflix and BBC around the world. An oath bound him to King Alfred. An oath bound him to Æthelflaed. And now an oath will wrench him away from the ancestral home he fought so hard to regain. For Uhtred has sworn that on King Edward’s death, he will kill two men. And now Edward is dying. A violent attack drives Uhtred south with a small band of warriors, and headlong into the battle for kingship. Plunged into a world of shifting alliances and uncertain loyalties, he will need all his strength and guile to overcome the fiercest warrior of them all. As two opposing Kings gather their armies, fate drags Uhtred to London, and a struggle for control that must leave one King victorious, and one dead. But fate – as Uhtred has learned to his cost – is inexorable. Wyrd bið ful ãræd. And Uhtred’s destiny is to stand at the heart of the shield wall once again…