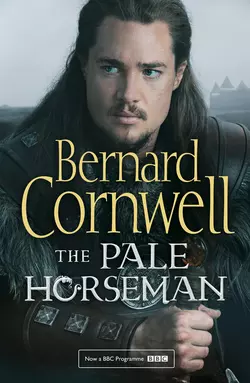

The Pale Horseman

Bernard Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 689.98 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: BBC2’s major TV series THE LAST KINGDOM is based on Bernard Cornwell’s bestselling novels on the making of England and the fate of his great hero, Uhtred of Bebbanburg. THE PALE HORSEMAN is the second book in the series.Season 2 of the epic TV series premiers this March.When peace is torn apart by bloody Danish steel, Uhtred must fight to save a king who distrusts him.Skeptical of a treaty between the Vikings and Wessex, Uhtred takes his talent for mayhem to Cornwall, gaining treasure and a mysterious woman on the way. But when he is accused of massacring Christians, he finds lies can be as deadly as steel.Still, when pious King Alfred flees to a watery refuge, it is the pagan warrior he relies on. Now Uhtred must fight a battle which will shape history – and confront the Viking with the banner of the white horse …Uhtred of Bebbanburg’s mind is as sharp as his sword. A thorn in the side of the priests and nobles who shape his fate, this Saxon raised by Vikings is torn between the life he loves and those he has sworn to serve.