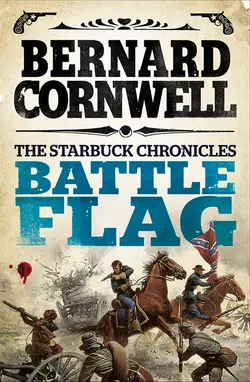

Battle Flag

Bernard Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1036.35 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The third volume in the Starbuck Chronicles. The battle for control of Richmond, the Confederate capital, continues through the hot summer of 1862.Captain Nate Starbuck, yankee fighting for the Southern cause, has to survive and win with his ragged Company in the bitter struggle not only against the formidable Northern army but equally in opposition to his own superiors who would like nothing better than to see Nate Starbuck dead and dishonoured.Starbuck’s courage is tested to the limit in his desperate manoeuvres to retrieve his own and the Legion’s honour in this the thrid narrative of Bernard Cornwell’s sweeping epic of the American Civil War.