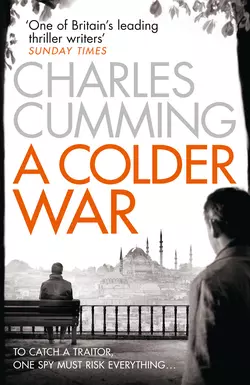

A Colder War

Charles Cumming

From the winner of the CWA Ian Fleming Steel Dagger 2012 for Best Thriller of the Year comes a gripping and suspenseful new spy novel. Perfect for fans of John le Carré, Charles Cumming is ‘the master of the modern spy thriller’ (Mail on Sunday)Thomas Kell is a disgraced agent who longs to come in from the cold. When MI6’s top spy in Turkey is killed in a mysterious plane crash, his chance arrives… for Kell is the only man Service Chief Amelia Levene can trust to investigate the accident.In Istanbul, Kell soon discovers that there is a traitor inside Western Intelligence. Then he meets Rachel- the dead spy’s daughter- and the stakes grow higher still.From London to Greece and into Eastern Europe, Kell tracks the mole. But a betrayal close to home transforms the operation into something more personal. Soon Kell will stop at nothing to see it through.

CHARLES CUMMING

A Colder War

Copyright (#ulink_ee4310d9-6a42-5b28-818e-25aa41ea7a42)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Charles Cumming 2014

Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Cover photographs © Josephine Pugh/Arcangel Images (cityscape); Henry Steadman (foreground and figure, right); Superstock (bench, seated man); Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com) (all other images).

Charles Cumming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Extract from The Double-Cross System by Sir John Masterman. Published by Vintage. Reprinted by permission from The Random House Group Limited.

Extract taken from ‘Postscript’ taken from The Spirit Level by Seamus Heaney © Estate of Seamus Heaney and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007467501

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2014 ISBN: 9780007467495

Version: 2018-06-04

Praise for A Colder War: (#ulink_bc442ad4-ebbb-5005-93c6-ae55ee304a4b)

‘The spy thriller has been on the ascendant in the past few years, breeding a bunch of talented writers, Cumming among the very best’ The Times

‘An espionage maestro … The levels of psychological insight are married to genuine narrative acumen – but anyone who has read his earlier books will expect no less’ Independent

‘A cleverly plotted spy tale’ Sun

‘Cumming’s prose is always lean and effective, but I was struck by the many times he injected phrases and descriptions so nice that I stopped to savour them’ Washington Post

‘A Colder War is more than an excellent thriller: it is also a novel that forces us to look behind the headlines and question some of our own comfortable assumptions’ Spectator

Dedication (#ulink_82dfdc38-0375-5461-ad55-541c1b222a85)

For Christian Spurrier

‘Certain persons … have a natural predilection to live in that curious world of espionage and deceit, and attach themselves with equal facility to one side or the other, so long as their craving for adventure of a rather macabre type is satisfied.’

John Masterman, The Double-Cross System

‘… You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.’

Seamus Heaney, ‘Postscript’

Contents

Cover (#uf9a036ca-ae18-5de6-a526-67207dc0a64d)

Title Page (#u936baf69-528a-5f7e-a43f-19719880f687)

Copyright (#u8c81abde-3ff0-59aa-8b61-f5649c0fe84f)

Praise for A Colder War (#u44dffcd2-3924-5ecd-8cb8-f9e61bd6ef3d)

Dedication (#ubd526926-a032-51fc-af7b-854970e54c2d)

Epigraph (#ubb9353b5-12b0-5b4b-857d-bb7efbf37b5e)

Turkey (#ua8cda2db-c0fd-5c05-a3e1-a7f8fadae499)

Chapter 1 (#u4d944785-b0fa-5ddd-b3f4-9477ca815ff0)

Chapter 2 (#ub37a7628-922e-5df1-8775-e5d4fb1cae37)

London: Three Weeks Later (#u0df68653-1f59-51a0-a8d2-d49a94d42731)

Chapter 3 (#u5c00e57b-2d37-5ecc-82f9-1b393a850389)

Chapter 4 (#u8cb6805e-dd45-5ad3-b4d8-65d8e0e908d0)

Chapter 5 (#udf78f2a6-8a40-51c8-8235-be284d214c6f)

Chapter 6 (#uae861263-f406-5976-ab76-b4fac8c88771)

Chapter 7 (#uab840d7c-5e73-59a9-b575-145f1dc575f5)

Chapter 8 (#u14ef43f9-dd08-5218-b58e-538e63f052b6)

Chapter 9 (#u900059b4-fea8-5ad4-94a1-e3cc66cd2b28)

Chapter 10 (#u40725a65-b2a3-57f8-97f1-e8c2d260196c)

Chapter 11 (#u268b5ce1-8f21-59f6-b696-3f760cec0e63)

Chapter 12 (#u1673a5d8-c00b-5c61-a941-ea7b07b65599)

Chapter 13 (#u189d092f-78cd-5cf4-8a51-1e556eeb9382)

Chapter 14 (#u2d296bb9-55fd-5f83-94fe-6b2dc89bb83e)

Chapter 15 (#ud77c23c1-1688-5e25-bee3-bcc892735fa2)

Chapter 16 (#u374e3a8f-3ff4-5710-86fa-fc6f5c810048)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 70 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 71 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Charles Cumming (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Turkey (#ulink_4b3fb26a-d284-5293-aabe-3ebd311829a9)

1 (#ulink_22734481-5011-535c-9206-ef2fa90013dc)

The American stepped away from the open window, passed Wallinger the binoculars and said: ‘I’m going for cigarettes.’

‘Take your time,’ Wallinger replied.

It was just before six o’clock on a quiet, dusty evening in March, no more than an hour until nightfall. Wallinger trained the binoculars on the mountains and brought the abandoned palace at İshak Paşa into focus. Squeezing the glasses together with a tiny adjustment of his hands, he found the mountain road and traced it west to the outskirts of Doğubayazit. The road was deserted. The last of the tourist taxis had returned to town. There were no tanks patrolling the plain, no dolmus bearing passengers back from the mountains.

Wallinger heard the door clunk shut behind him and looked back into the room. Landau had left his sunglasses on the furthest of the three beds. Wallinger crossed to the chest of drawers and checked the screen on his BlackBerry. Still no word from Istanbul; still no word from London. Where the hell was HITCHCOCK? The Mercedes was supposed to have crossed into Turkey no later than two o’clock; the three of them should have been in Van by now. Wallinger went back to the window and squinted over the telegraph poles, the pylons and the crumbling apartment blocks of Doğubayazit. High above the mountains, an aeroplane was moving west to east in a cloudless sky, a silent white star skimming towards Iran.

Wallinger checked his watch. Five minutes past six. Landau had pushed the wooden table and the chair in front of the window; the last of his cigarettes was snuffed out in a scarred Efes Pilsen ashtray now bulging with yellowed filters. Wallinger tipped the contents out of the window and hoped that Landau would bring back some food. He was hungry and tired of waiting.

The BlackBerry rumbled on top of the chest of drawers; Wallinger’s only means of contact with the outside world. He read the message.

Vertigo is on at 1750. Get three tickets

It was the news he had been waiting for. HITCHCOCK and the courier had made it through the border at Gürbulak, on the Turkish side, at ten to six. If everything went according to plan, within half an hour Wallinger would have sight of the vehicle on the mountain road. From the chest of drawers he pulled out the British passport, sent by diplomatic bag to Ankara a week earlier. It would get HITCHCOCK through the military checkpoints on the road to Van; it would get him on to a plane to Ankara.

Wallinger sat on the middle of the three beds. The mattress was so soft it felt as though the frame was giving way beneath him. He had to steady himself by sitting further back on the bed and was taken suddenly by a memory of Cecilia, his mind carried forward to the prospect of a few precious days in her company. He planned to fly the Cessna to Greece on Wednesday, to attend the Directorate meeting in Athens, then to cross over to Chios in time to meet Cecilia for supper on Thursday evening.

The tickle of a key in the door. Landau came back into the room with two packets of Prestige Filters and a plate of pide.

‘Got us something to eat,’ he said. ‘Anything new?’

The pide was giving off a tart smell of warm curdled cheese. Wallinger took the chipped white plate and rested it on the bed.

‘They made it through Gürbulak just before six.’

‘No trouble?’ It didn’t sound as though Landau cared much about the answer. Wallinger took a bite of the soft, warm dough. ‘Love this stuff,’ the American said, doing the same. ‘Kinda like a boat of pizza, you know?’

‘Yes,’ said Wallinger.

He didn’t like Landau. He didn’t trust the operation. He no longer trusted the Cousins. He wondered if Amelia had been at the other end of the text, worrying about Shakhouri. The perils of a joint operation. Wallinger was a purist and, when it came to inter-agency cooperation, wished that they could all just keep themselves to themselves.

‘How long do you think we’ll have to wait?’ Landau said. He was chewing noisily.

‘As long as it takes.’

The American sniffed, broke the seal on one of the packets of cigarettes. There was a beat of silence between them.

‘You think they’ll stick to the plan or come down on the 100?’

‘Who knows?’

Wallinger stood at the window again, sighted the mountain through the binoculars. Nothing. Just a tank crawling across the plain: making a statement to the PKK, making a statement to Iran. Wallinger had the Mercedes’ numberplate committed to memory. Shakhouri had a wife, a daughter, a mother sitting in an SIS-funded flat in Cricklewood. They had been waiting for days. They would want to know that their man was safe. As soon as Wallinger saw the vehicle, he would message London with the news.

‘It’s like clicking “refresh” over and over.’

Wallinger turned and frowned. He hadn’t understood Landau’s meaning. The American saw his confusion and grinned through his thick brown beard. ‘You know, all this waiting around. Like on a computer. When you’re waiting for news, for updates. You click “refresh” on the browser?’

‘Ah, right.’ Of all people, at that moment Paul Wallinger thought of Tom Kell’s cherished maxim: ‘Spying is waiting.’

He turned back to the window.

Perhaps HITCHCOCK was already in Doğubayazit. The D100 was thick with trucks and cars at all times of the day and night. Maybe they’d ignored the plan to use the mountain road and come on that. There was still a dusting of snow on the peaks; there had been a landslide only two weeks earlier. American satellites had shown that the pass through Besler was clear, but Wallinger had come to doubt everything they told him. He had even come to doubt the messages from London. How could Amelia know, with any certainty, who was in the car? How could she trust that HITCHCOCK had made it out of Tehran? The exfil was being run by the Cousins.

‘Smoke?’ Landau said.

‘No thanks.’

‘Your people say anything else?’

‘Nothing.’

The American reached into his pocket and pulled out a cell phone. He appeared to read a message, but kept the contents to himself. Dishonour among spies. HITCHCOCK was an SIS Joe, but the courier, the exfil, the plan to pick Shakhouri up in Doğubayazit and fly him out of Van, that was all Langley. Wallinger would happily have run the risk of putting him on a plane from Imam Khomeini to Paris and lived with the consequences. He heard the snap of the American’s lighter and caught a backdraught of tobacco smoke, then turned to the mountains once again.

The tank had now parked at the side of the mountain road, shuffling from side to side, doing the Tiananmen twist. The gun turret swivelled north-east so that the barrel was pointing in the direction of Mount Ararat. Right on cue, Landau said: ‘Maybe they found Noah’s Ark up there,’ but Wallinger wasn’t in the mood for jokes.

Clicking refresh on a browser.

Then, at last, he saw it. A tiny bottle-green dot, barely visible against the parched brown landscape, moving towards the tank. The vehicle was so small it was hard to follow through the lens of the binoculars. Wallinger blinked, cleared his vision, looked again.

‘They’re here.’

Landau came to the window. ‘Where?’

Wallinger passed him the binoculars. ‘You see the tank?’

‘Yup.’

‘Follow the road up …’

‘… OK. Yeah. I see them.’

Landau put down the binoculars and reached for the video camera. He flipped off the lens cap and began filming the Mercedes through the window. Within a minute, the vehicle was close enough to be picked out with the naked eye. Wallinger could see the car speeding along the plain, heading towards the tank. There was half a kilometre between them. Three hundred metres. Two.

Wallinger saw that the tank barrel was still pointing away from the road, up towards Ararat. What happened next could not be explained. As the Mercedes drove past the tank, there appeared to be an explosion in the rear of the vehicle that lifted up the back axle and propelled the car forward in a skid with no sound. The Mercedes quickly became wreathed in black smoke and then rolled violently from the road as flames burst from the engine. There was a second explosion, then a larger ball of flame. Landau swore very quietly. Wallinger stared in disbelief.

‘What the hell happened?’ the American said, lowering the camera.

Wallinger turned from the window.

‘You tell me,’ he replied.

2 (#ulink_186120be-307c-5651-861a-7298a567eae4)

Ebru Eldem could not remember the last time she had taken the day off. ‘A journalist,’ her father had once told her, ‘is always working’. And he was right. Life was a permanent story. Ebru was always sniffing out an angle, always felt that she was on the brink of missing out on a byline. When she spoke to the cobbler who repaired the heels of her shoes in Arnavutköy, he was a story about dying small businesses in Istanbul. When she chatted to the good-looking stallholder from Konya who sold fruit in her local market, he was an article about agriculture and economic migration within Greater Anatolia. Every number in her phone book – and Ebru reckoned she had better contacts than any other journalist of her age and experience in Istanbul – was a story waiting to open up. All she needed was the energy and the tenacity to unearth it.

For once, however, Ebru had set aside her restlessness and ambition and, in a pained effort to relax, if only for a single day, turned off her mobile phone and set her work to one side. That was quite a sacrifice! From eight o’clock in the morning – the lie-in, too, was a luxury – to nine o’clock at night, Ebru avoided all emails and Facebook messages and lived the life of a single woman of twenty-nine with no ties to work and no responsibilities other than to her own relaxation and happiness. Granted, she had spent most of the morning doing laundry and cleaning up the chaos of her apartment, but thereafter she had enjoyed a delicious lunch with her friend Banu at a restaurant in Beşiktaş, shopped for a new dress on Istiklal, bought and read ninety pages of the new Elif Şafak novel in her favourite coffee house in Cihangir, then met Ryan for martinis at Bar Bleu.

In the five months that they had known one another, their relationship had grown from a casual, no-strings-attached affair to something more serious. When they had first met, their get-togethers had taken place almost exclusively in the bedroom of Ryan’s apartment in Tarabya, a place where – Ebru was sure – he took other girls, but none with whom he had such a connection, none with whom he would be so open and raw. She could sense it not so much by the words that he whispered into her ear as they made love, but more by the way that he touched her and looked into her eyes. Then, as they had grown to know one another, they had spoken a great deal about their respective families, about Turkish politics, the war in Syria, the deadlock in Congress – all manner of subjects. Ebru had been surprised by Ryan’s sensitivity to political issues, his knowledge of current affairs. He had introduced her to his friends. They had talked about travelling together and even meeting one another’s parents.

Ebru knew that she was not beautiful – well, certainly not as beautiful as some of the girls looking for husbands and sugar daddies in Bar Bleu – but she had brains and passion and men had always responded to those qualities in her. When she thought about Ryan, she thought about his difference to all the others. She wanted the heat of physical contact, of course – a man who knew how to be with her and how to please her – but she also craved his mind and his energy, the way he treated her with such affection and respect.

Today was a typical day in their relationship. They drank too many cocktails at Bar Bleu, went for dinner at Meyra, talked about books, the recklessness of Hamas and Netanyahu. Then they stumbled back to Ryan’s apartment at midnight, fucking as soon as they had closed the door. The first time was in the lounge, the second time in his bedroom with the kilims bunched up on the floor and the shade still not fixed on the standing lamp beside the armchair. Ebru had lain there afterwards in his arms, thinking that she would never want for another man. Finally she had found someone who understood her and made her feel entirely herself.

The smell of Ryan’s breath and the sweat of his body were still all over Ebru as she slipped out of the building just after two o’clock, Ryan snoring obliviously. She took a taxi to Arnavutköy, showered as soon as she was home, and climbed into bed, intending to return to work just under four hours later.

Burak Turan of the Turkish National Police reckoned you could divide people into two categories: those who didn’t mind getting up early in the morning; and those who did. As a rule for life it had served him well. The people who were worth spending time with didn’t go to sleep straight after Muhteşem Yüzyil and jump out of bed with a smile on their face at half-past six in the morning. You had to watch people like that. They were control freaks, workaholics, religious nuts. Turan considered himself to be a member of the opposite category of person: the type who liked to extract the best out of life; who was creative and generous and good in a crowd. After finishing work, for example, he liked to wind down with a tea and a chat at a club on Mantiklal near the precinct station. His mother, typically, would cook him dinner, then he’d head out to a bar and get to bed by midnight or one, sometimes later. Otherwise, when did people find the time to enjoy themselves? When did they meet girls? If you were always concentrating on work, if you were always paranoid about getting enough sleep, what was left to you? Burak knew that he wasn’t the most hard-working officer in the barracks, happy to tick over while other, better-connected guys got promoted ahead of him. But what did he care about that? As long as he could keep the salary, the job, visit Cansu on weekends and watch Galatasaray games at the Turk Telekom every second Saturday, he reckoned he had life pretty well licked.

But there were drawbacks. Of course there were. As he got older, he didn’t like taking so many orders, especially from guys who were younger than he was. That happened more and more. A generation coming up behind him, pushing him out of the way. There were too many people in Istanbul; the city was so fucking crowded. And then there were the dawn raids, dozens of them in the last two years – a Kurdish problem, usually, but sometimes something different. Like this morning. A journalist, a woman who had written about Ergenekon or the PKK – Burak wasn’t clear which – and word had come down to arrest her. The guys were talking about it in the van as they waited outside her apartment building. Cumhuriyet writer. Eldem. Lieutenant Metin, who looked like he hadn’t been to bed in three days, mumbled something about ‘links to terrorism’ as he strapped on his vest. Burak couldn’t believe what some people were prepared to swallow. Didn’t he know how the system worked? Ten to one Eldem had riled somebody in the AKP, and an Erdoğan flunkie had spotted a chance to send out a message. That was how government people always operated. You had to keep an eye on them. They were all early risers.

Burak and Metin were part of a three-man team ordered to take Eldem into custody at five o’clock in the morning. They knew what was wanted. Make a racket, wake the neighbours, scare the blood out of her, drag the detainee down to the van. A few weeks ago, on the last raid they did, Metin had picked up a framed photograph in some poor bastard’s living room and dropped it on the floor, probably because he wanted to be like the cops on American TV. But why did they have to do it in the middle of the night? Burak could never work that out. Why not just pick her up on the way to work, pay a visit to Cumhuriyet? Instead, he’d had to set his fucking alarm for half-past three in the morning, show himself at the precinct at four, then sit around in the van for an hour with that weight in his head, the numb fatigue of no sleep, his muscles and his brain feeling soft and slow. Burak got tetchy when he was like that. Anybody did anything to rile him, said something he didn’t like, if there was a delay in the raid or any kind of problem – he’d snap them off at the knees. Food didn’t help, tea neither. It wasn’t a blood sugar thing. He just resented having to haul his arse out of bed when the rest of Istanbul was still fast asleep.

‘Time?’ said Adnan. He was sitting in the driver’s seat, too lazy even to look at a clock.

‘Five,’ said Burak, because he wanted to get on with it.

‘Ten to,’ said Metin. Burak shot him a look.

‘Fuck it,’ said Adnan. ‘Let’s go.’

The first Ebru knew of the raid was a noise very close to her face, which she later realized was the sound of the bedroom door being kicked in. She sat up in bed – she was naked – and screamed, because she thought a gang of men were going to rape her. She had been dreaming of her father, of her two young nephews, but now three men were in her cramped bedroom, throwing clothes at her, shouting at her to get dressed, calling her a ‘fucking terrorist’.

She knew what it was. She had dreaded this moment. They all did. They all censored their words, chose their stories carefully, because a line out of place, an inference here, a suggestion there, was enough to land you in prison. Modern Turkey. Democratic Turkey. Still a police state. Always had been. Always would be.

One of them was dragging her now, saying she was being too slow. To Ebru’s shame, she began to cry. What had she done wrong? What had she written? It occurred to her, as she covered herself, pulled on some knickers, buttoned up her jeans, that Ryan would help. Ryan had money and influence and would do what he could to save her.

‘Leave it,’ one of them barked. She had tried to grab her phone. She saw the surname on the cop’s lapel badge: TURAN.

‘I want a lawyer,’ she screamed.

Burak shook his head. ‘No lawyer is going to help you,’ he said. ‘Now put on a fucking shirt.’

London Three Weeks Later (#ulink_b9ae5115-cd72-5c16-9d19-3b363a87441b)

3 (#ulink_a616bcd4-b220-560f-b7bf-646d6bc2813c)

Thomas Kell had only been standing at the bar for a few seconds when the landlady turned to him, winked, and said: ‘The usual, Tom?’

The usual. It was a bad sign. He was spending four nights out of seven at the Ladbroke Arms, four nights out of seven drinking pints of Adnams Ghost Ship with only The Times quick crossword and a packet of Winston Lights for company. Perhaps there was no alternative for disgraced spooks. Cold-shouldered by the Secret Intelligence Service eighteen months earlier, Kell had been in a state of suspended animation ever since. He wasn’t out, but he wasn’t in. His part in saving the life of Amelia Levene’s son, François Malot, was known only to a select band of high priests at Vauxhall Cross. To the rest of the staff at MI6, Thomas Kell was still ‘Witness X’, the officer who had been present at the aggressive CIA interrogation of a British national in Kabul and who had failed to prevent the suspect’s subsequent rendition to a black prison in Cairo, and on to the gulag of Guantanamo.

‘Thanks, Kathy,’ he said, and planted a five-pound note on the bar. A well-financed German was standing beside him, flicking through the pages of the FT Weekend and picking at a bowl of wasabi peas. Kell collected his change, walked outside and sat at a picnic table under the fierce heat of a standing gas fire. It was dusk on a damp Easter Sunday, the pub – like the rest of Notting Hill – almost empty. Kell had the terrace to himself. Most of the local residents appeared to be out of town, doubtless at Gloucestershire second homes or skiing lodges in the Swiss Alps. Even the well-tended police station across the street looked half-asleep. Kell took out the packet of Winston and rummaged around for his lighter; a gold Dunhill, engraved with the initials P.M. – a private memento from Levene, who had risen to MI6 Chief the previous September.

‘Every time you light a cigarette, you can think of me,’ she had said with a low laugh, pressing the lighter into the palm of his hand. A classic Amelia tactic: seemingly intimate and heartfelt, but ultimately deniable as anything other than a platonic gift between friends.

In truth, Kell had never been much of a smoker, but recently cigarettes had afforded a useful punctuation to his unchanging days. In his twenty-year career as a spy, he had often carried a packet as a prop: a light could start a conversation; a cigarette would put an agent at ease. Now they were part of the furniture of his solitary life. He felt less fit as a consequence and spent a lot more money. Most mornings he would wake and cough like a dying man, immediately reaching for another nicotine kick-start to the day. But he found that he could not function without them.

Kell was living in what a former colleague had described as the ‘no-man’s land’ of early middle-age, in the wake of a job which had imploded and a marriage which had failed. At Christmas, his wife, Claire, had finally filed for divorce and begun a new relationship with her lover, Richard Quinn, a twice-married hedge fund Peter Pan with a £14 million townhouse in Primrose Hill and three teenage sons at St Paul’s. Not that Kell regretted the split, nor resented Claire the upgrade in lifestyle; for the most part he was relieved to be free of a relationship that had brought neither of them much in the way of happiness. He hoped that Dick the Wonder Schlong – as Quinn was affectionately known – would bring Claire the fulfilment she craved. Being married to a spy, she had once told him, was like being married to half a person. In her view, Kell had been physically and emotionally separate from her for years.

A sip of the Ghost. It was Kell’s second pint of the evening and tasted soapier than the first. He flicked the half-smoked cigarette into the street and took out his iPhone. The green ‘Messages’ icon was empty; the ‘Mail’ envelope identically blank. He had finished The Times crossword half an hour earlier and had left the novel he was reading – Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending – on the kitchen table in his flat. There seemed little to do but drink the pint and look out at the listless street. Occasionally a car would roll down the road or a local resident drag past with a dog, but London was otherwise uncharacteristically silent; it was like listening to the city through the muffle of headphones. The eerie quiet only added to Kell’s sense of restlessness. He was not a man prone to self-pity, but nor did he want to spend too many more nights drinking alone on the terrace of an upmarket gastro pub in West London, waiting to see if Amelia Levene would give him his job back. The public inquiry into Witness X was dragging its heels; Kell had been hanging on almost two years to find out whether he would be cleared of all charges or laid out as a sacrificial lamb. With the exception of the three-week operation to rescue Amelia’s son, François, the previous summer, and a one-month contract working due diligence for a corporate espionage firm in Mayfair, that was too long out of the game. He wanted to get back to work. He wanted to spy again.

Then – a miracle. The iPhone lit up. ‘Amelia L3’ appeared on the screen. It was like a sign from the God in whom Kell still occasionally believed. He picked up before the first ring was through.

‘Speak of the devil.’

‘Tom?’

He could tell immediately that something was wrong. Amelia’s customarily authoritative voice was shaky and uncertain. She had called him from her private number, not a landline or encrypted Service phone. It had to be personal. Kell thought at first that something must have happened to François, or that Amelia’s husband, Giles, had been killed in an accident.

‘It’s Paul.’

That winded him. Kell knew that she could only be talking about Paul Wallinger.

‘What’s happened? Is he all right?’

‘He’s been killed.’

4 (#ulink_90fb7605-febd-5299-8485-ce4d880b8dc0)

Kell hailed a cab on Holland Park Avenue and was outside Amelia’s house in Chelsea within twenty minutes. He was about to ring the bell when he felt the loss of Wallinger like something pulling apart inside him and had to take a moment to compose himself. They had joined SIS in the same intake. They had risen through the ranks together, fast-track brothers winning the pick of overseas postings across the post-Cold War constellation. Wallinger, an Arabist, nine years older, had served in Cairo, Riyadh, Tehran and Damascus, before Amelia had handed him the top job in Turkey. In what he had often thought of as a parallel, shadow career, Kell, the younger brother, had worked in Nairobi, Baghdad, Jerusalem and Kabul, tracking Wallinger’s rise as the years rolled by. Staring down the length of Markham Street, he remembered the thirty-four-year-old wunderkind he had first encountered on the IONEC training course in the autumn of 1990, Wallinger’s scores, his intellect, his ambition just that much sharper than his own.

But Kell wasn’t here because of work. He hadn’t rushed to Amelia’s side in order to offer dry advice on the political and strategic fallout from Wallinger’s untimely death. He was here as her friend. Thomas Kell was one of very few people within SIS who knew the truth about the relationship between Amelia Levene and Paul Wallinger. The pair had been lovers for many years, a stop-start, on-off affair which had begun in London in the late 1990s and continued, with both parties married, right up until Amelia’s selection as Chief.

He rang the bell, swiped a wave at the security camera, heard the lock buzzing open. There was no guard in the atrium, no protection officer on duty. Amelia had probably persuaded him to take the night off. As ‘C’, she was entitled to a grace-and-favour Service apartment, but the house belonged to her husband. Kell did not expect to find Giles Levene at home. For some time the couple had been estranged, Giles spending most of his time at Amelia’s house in the Chalke Valley, or tracing the ever-lengthening branches of his family tree as far afield as Cape Town, New England, the Ukraine.

‘You stink of cigarettes,’ she said as she opened the door into the hall, offering up a taut, pale cheek for Kell to kiss. She was wearing jeans and a loose cashmere sweater, socks but no shoes. Her eyes looked clear and bright, though he suspected that she had been crying; her skin had the sheen of recent tears.

‘Giles home?’

Amelia caught Kell’s eyes quickly, skipping on the question, as though wondering whether or not to answer it truthfully.

‘We’ve decided to try for separation.’

‘Oh Christ, I’m so sorry.’

The news acted on him in conflicting ways. He was sorry that Amelia was about to experience the singular agony of divorce, but glad that she would finally be free of Giles, a man so boring he was dubbed ‘The Coma’ in the corridors of Vauxhall Cross. They had married one another largely for convenience – Amelia had wanted a steadfast, back-seat man with plenty of money who would not block her path to the top; Giles had wanted Amelia as his prize, for her access to the great and the good of London society. Like Claire and Kell, they had never been able to have children. Kell suspected that the sudden appearance of Amelia’s son, François, eighteen months earlier, had been the relationship’s last straw.

‘It’s a great shame, yes,’ she said. ‘But the best thing for both of us. Drink?’

This was how she moved things on. We’re not going to dwell on this, Tom. My marriage is my private business. Kell stole a glance at her left hand as she led him into the sitting room. Her wedding ring was still in place, doubtless to silence the rumour mill in Whitehall.

‘Whisky, please,’ he said.

Amelia had reached the cabinet and turned around, an empty glass in hand. She gave a nod and a half-smile, like somebody recognizing the melody of a favourite song. Kell heard the clunk and rattle of a single ice cube spinning into the glass, then the throaty glug of malt. She knew how he liked it: three fingers, then just a splash of water to open it up.

‘And how are you?’ she asked, handing him the drink. She meant Claire, she meant his own divorce. They were both in the same club now.

‘Oh, same old, same old,’ he said. He felt like a man at the end of a date who had been invited in for coffee and was struggling for conversation. ‘Claire’s with Dick the Wonder Schlong. I’m house-sitting a place in Holland Park.’

‘Holland Park?’ she said, with an escalating tone of surprise. It was as though Kell had moved up a couple of rungs on the social ladder. A part of him was dismayed that she did not already know where he was living. ‘And you think—’

He interrupted her. The news about Wallinger was hanging in the space between them. He did not want to ignore it much longer.

‘Look, I’m sorry about Paul.’

‘Don’t be. You were kind to rush over.’

He knew that she would have spent the previous hours picking over every moment she had shared with Wallinger. What do lovers eventually remember about one another? Their eyes? Their touch? A favourite poem or song? Amelia had almost word-perfect recall for conversations, a photographic memory for faces, images, contexts. Their affair would now be a palace of memories through which she could stroll and recollect. The relationship had been about much more than the thrill of adultery; Kell knew that. At one point, in a moment of rare candour, Amelia had told Kell that she was in love with Paul and was thinking of leaving Giles. He had warned her off; not out of jealousy, but because he knew of Wallinger’s reputation as a womanizer and feared that the relationship, if it became public knowledge, would skewer Amelia’s career, as well as her happiness. He wondered now if she regretted taking his advice.

‘He was in Greece,’ she began. ‘Chios. An island there. I don’t really know why. Josephine wasn’t with him.’

Josephine was Wallinger’s wife. When she wasn’t visiting her husband in Ankara, or staying on the family farm in Cumbria, she lived less than a mile away, in a small flat off Gloucester Road.

‘Holiday?’ Kell asked.

‘I suppose.’ Amelia had a whisky of her own and drank from it. ‘He hired a plane. You know how he loved to fly. Attended a Directorate meeting at the Station in Athens, stopped off on Chios on the way home. He was taking the Cessna back to Ankara. There must have been something wrong with the aircraft. Mechanical fault. They found debris about a hundred miles north-east of Izmir.’

‘No body?’

Kell saw Amelia flinch and winced at his own insensitivity. That body was her body. Not just the body of a colleague; the body of a lover.

‘Something was found,’ she replied, and he felt sick at the image.

‘I’m so sorry.’

She came towards him and they embraced, glasses held awkwardly to one side, like the start of a dance with no rhythm. Kell wondered if she was going to cry, but as she pulled away he saw that she was entirely composed.

‘The funeral is on Wednesday,’ she said. ‘Cumbria. I wondered if you would come with me?’

5 (#ulink_b4f29ce3-c9af-53fd-a049-fd8763ef1248)

The agent known to SVR officer Alexander Minasian by the cryptonym ‘KODAK’ had near-perfect conversational recall and a photographic memory once described by an admiring colleague as ‘pixel sharp’. As winter turned to spring in Istanbul, his signals to Minasian were becoming more frequent. KODAK recalled their conversation at the Grosvenor House Hotel in London almost three years earlier:

Every day, between nine o’clock and nine thirty in the morning, and between seven o’clock and seven thirty in the evening, we will have a person in the tea house. Somebody who knows your face, somebody who knows the signal. This is easy for us to arrange. I will arrange it. When you find yourself working in Ankara, the routine will be the same.

KODAK would typically leave his apartment between seven and eight o’clock in the morning, undertake no discernible counter-surveillance, drive his car or – more usually – take a taxi to Istiklal Caddesi, walk down the narrow passage opposite the Russian Consulate, enter the tea house and sit down. Alternatively, he would leave work at the usual time, take a train into the city, browse in some of the bookshops and clothing stores on Istiklal, then stop for a glass of tea at the appointed time.

Whenever you have documents for me, you only need to go to the tea house at these times and to present yourself to us. You will not need to know who is watching for you. You will not need to look around for faces. Just wear the signal that we have agreed, take a cup of tea or take a coffee, and we will see you. You can sit inside the café or you can sit outside the café. It does not matter. There will always be somebody there.

Of course KODAK did not wish to establish a pattern. Whenever he was in the area around Taksim, day or night, he would try to go to the tea house, ostensibly to practise his Turkish with the pretty young waitress, to play backgammon, or simply to read a book. He frequented other tea houses in the area, other restaurants and bars, often purposefully wearing near-identical clothing.

If it suits you, bring a friend. Bring somebody who does not know the significance of the occasion! If you see somebody leaving while you are there, do not follow them. Of course not. This would be dangerous. You will not know who I have sent to look for you. You will not know who might be watching them, just as you will not know who might be watching you. This is why we do not leave a trace. No more chalk marks on walls. No more stickers. I have always preferred the static system, something that cannot be noticed, except by the eye which has been trained to see it. The movement of a vase of flowers in a room. The appearance of a bicycle on a balcony. Even the colour of a pair of socks! All these things can be used to communicate a signal.

KODAK liked Minasian. He admired his courage, his instincts, his professionalism. Together they had been able to do significant work; together they might bring about extraordinary change. But he felt that the Russian, from time to time, could be somewhat melodramatic.

If you feel that your position has been compromised, do not show yourself at the tea house or at the Ankara location. Instead, obtain or borrow a cell phone and text the word BEŞIKTAŞto my number. If this is not possible, for whatever reason – you cannot obtain a signal, you cannot obtain a phone – go to a callbox or other landline and speak this word when there is an answer. If we contact you using this word, it is our belief that your work for us has been discovered and that you should leave Turkey.

It seemed highly improbable to KODAK that he would ever be suspected of treachery, far less caught in the act of handing secrets to the SVR. He was too clever, too cautious, his tracks too well covered. Nevertheless, he remembered the meeting points, and the crash instructions, and committed the numbers associated with them to memory.

There are three potential meeting points in the event of exposure. Remember them. If you say BEŞIKTAŞONE, a contact will meet you in the courtyard of the Blue Mosque at the time agreed. He will make himself known to you and you will follow him. If you consider Turkey to be unsafe, make your way across the border to Bulgaria with the message BEŞIKTAŞTWO. Do not, under any circumstances, attempt to board an aeroplane. A contact will make himself known to you at the time agreed, in the bar of the Grand Hotel in Sofia. In exceptional circumstances, if you feel that it is necessary to cross into former Soviet territory, where you will be safer and more easily escorted to Moscow, there are boats from Istanbul. You will always be welcome in Odessa. The code for this crash meeting is BEŞIKTAŞTHREE.

6 (#ulink_6402dc90-0174-5805-8606-640cf9120523)

It had dawned on Thomas Kell that the number of funerals he was attending in a calendar year had begun to outstrip the number of weddings. As he travelled north with Amelia in a packed first-class carriage from Euston, he felt as though the change had occurred almost overnight: one moment he had been a young man in a morning suit throwing confetti over rapturous couples every third weekend in summer; the next he had somehow morphed into a veteran forty-something spook, flying in from Kabul to bury a friend or relative dead from alcohol or cancer. Looking around the train gave Kell the same feeling: he was older than almost everyone in the carriage. What had happened to the intervening years? Even the ticket inspector appeared to have been born after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

‘You look tired,’ Amelia said, looking up from an op-ed in the Independent. She had taken to wearing half-moon reading glasses and almost looked her age.

‘Gee thanks,’ Kell replied.

She was seated opposite him at a table sticky with half-eaten croissants and discarded coffee cups. Beside her, oblivious to Amelia’s rank and distinction, a clear-skinned student with an upgraded ticket to Lancaster was playing Solitaire on a Samsung tablet. Both had their backs to the direction of travel as the fields and rivers of England whistled by. Kell was jammed in at a window seat, trying to avoid touching thighs with an overweight businesswoman who kept falling asleep in a Trollope novel. He had packed a bag because he was planning to stay in the north for several days. Why hammer back to London when he could go walking in Cumbria and eat two-star Michelin food at L’Enclume? There was nothing and nobody waiting for him back home in Holland Park. Just the Ladbroke Arms and another pint of Ghost Ship.

Kell was wearing a charcoal lounge suit, a white shirt and a black tie; Amelia was dressed in a dark blue suit and black overcoat. Their funereal garb drew occasional sympathetic stares as they walked across Preston station. Amelia had booked a cab on SIS and, by half-past twelve, they were wandering around Cartmel like a married couple, Kell checking into his hotel, Amelia calling the Office more than once to ensure that everything back in London was running smoothly.

They were eating chicken pie in a pub in the centre of the village when Kell spotted George Truscott at the bar, ordering a half-pint of lager. As Assistant to the Chief, Truscott had been lined up to succeed Simon Haynes as ‘C’, before Amelia had stolen his prize. It had been Truscott, a corporatized desk jockey of suffocating ambition, who had authorized Kell’s presence at the interrogation of Yassin Gharani; and it had been Truscott, more than any other colleague, who had gladly thrown Kell to the wolves when the Service needed a fall guy for the sins of extraordinary rendition. Roughly three minutes after taking over as Chief, Amelia had dispatched Truscott to Bonn, dangling the top job in Germany as a carrot. Neither of them had seen him since.

‘Amelia!’

Truscott had turned from the bar and was carrying his half-pint across the pub, like a student learning how to drink during Fresher’s Week. Kell wondered if he should bother disguising his contempt for the man who had ruined his career, but stage-managed a smile, largely out of respect for the sombre occasion. Amelia, to whom false expressions of loyalty and affection came as naturally as blinking, stood up and warmly shook Truscott’s hand. A passer-by, glancing at their table, would have concluded that both were delighted to see him.

‘I didn’t know you were coming, George. Did you fly in from Bonn?’

‘Berlin, actually,’ Truscott replied, hinting archly at work of incalculable importance to the secret state. ‘And how are you, Tom?’

Kell could see the wheels of Truscott’s ruthless, back-covering mind turning behind the question; that cunning and inexhaustibly competitive personality with which he had wrestled so long in the final months of his career. Truscott’s thoughts might as well have appeared as bubbles above his narrow, bone-white scalp. Why is Kell with Levene? Has she brought him in from the cold? Has Witness X been forgiven? Kell glimpsed the tremor of panic in Truscott’s wretched and empty soul, his profound fear that Amelia was about to make Kell ‘H/Ankara’, leaving Truscott with the backwater of Bonn; a Cold War, EU hang-up barely relevant in the age of Asia Reset and the Arab Spring.

‘Oh look, there’s Simon.’

Amelia had spotted Haynes coming out of the Gents. Her predecessor produced a beaming smile that instantly evaporated when he saw Kell and Truscott in such close proximity. Amelia allowed him to kiss both her cheeks, then watched as the male spooks became stiffly reacquainted. Kell barely took in the various platitudes and clichés with which Haynes greeted him. Yes, it was a great tragedy about Paul. No, Kell hadn’t yet found a permanent job in the private sector. Indeed it was frustrating that the public inquiry had stalled yet again. Before long, Haynes had shuffled off in the direction of Cartmel Priory, Truscott trotting along beside him as though he still believed that Haynes could influence his career.

‘Simon wanted to give the eulogy for Paul,’ Amelia said, checking her reflection in a nearby mirror as she slipped into her coat. They had polished off their chicken pies, split the bill. ‘He didn’t seem to think it would be a problem. I had to put a stop to it.’

Having collected his knighthood from Prince Charles the previous autumn, Haynes had appeared at The Sunday Times Literary Festival, spoken at an Intelligence Squared debate at the Royal Geographical Society and enthusiastically listed his favourite records on Desert Island Discs. As such, he was the first outgoing Chief of the Service actively to be seen to be benefiting, both commercially and in terms of his own public profile, from his former career. For Haynes to have given the eulogy at Wallinger’s funeral would have exposed the deceased as a spy to the many friends and neighbours who had gathered in Cartmel under the impression that he had been simply a career diplomat, or even a gentleman farmer.

‘A bad habit we’ve acquired from the Security Service,’ Amelia continued. She was wearing a gold necklace and briefly touched the chain. ‘It’ll be memoirs next. Whatever happened to discretion? Why couldn’t Simon just have joined BP like the rest of them?’

Kell grinned but wondered if Amelia was giving him a tacit warning: Don’t go public with Witness X. Surely she knew him well enough to realize that he would never betray the Service, far less breach her trust?

‘You ready for this?’ he asked, as they turned towards the door. Kell had been drinking a glass of Rioja and drained the last of it as he threw a few pound coins on to the table as a tip. Amelia found his eyes and, for an instant, looked vulnerable to what lay ahead. As they walked outside into the crystal afternoon sunshine, she briefly squeezed his hand and said: ‘Wish me luck.’

‘You’ll be fine,’ he told her. ‘The last thing you’ve ever needed is luck.’

He was right, of course. Shortly after three o’clock, as the congregation rose as one to acknowledge the arrival of Josephine Wallinger, Amelia assumed the dignified bearing of a leader and Chief, her body language betraying no hint that the man three hundred people had come to mourn had ever been anything more to her than a highly regarded colleague. Kell, for his part, felt oddly detached from the service. He sang the hymns, he listened to the lessons, he nodded through the vicar’s eulogy, which paid appropriately oblique tribute to a ‘self-effacing man’ who had been ‘a loyal servant to his country’. Yet Kell was distracted. Afterwards, making his way to the graveside, he heard an unseen mourner utter the single word ‘Hammarskjöld’ and knew that the conspiracy theories were gathering pace. Dag Hammarskjöld was the Swedish Secretary of the United Nations who had been killed in a plane crash in 1961, en route to securing a peace deal that might have prevented civil war in the Congo. Hammarskjöld’s DC6 had crashed in a forest in former Rhodesia. Some claimed that the plane had been shot down by mercenaries; others that SIS itself, in collusion with the CIA and South African intelligence, had sabotaged the flight. Since hearing the news on Sunday, Kell had been nagged by an unsettling sense that there had been foul play involved in Wallinger’s death. He could not say precisely why he felt this way – other than that he had always known Paul to be a meticulous pilot, thorough to the point of paranoia with pre-flight checks – yet the whispered talk of Hammarskjöld seemed to cement the suspicion in his mind. Looking around at the faceless spooks, ghosts of bygone ops from a dozen different Services, Kell felt that somebody, somewhere in the cramped churchyard, knew why Paul Wallinger’s plane had plunged from the sky.

The mourners shuffled forward, perhaps as many as two hundred men and women, forming a loose rectangle, ten-deep, on all four sides of the grave. Kell saw CIA officers, representatives from Canadian intelligence, three members of the Mossad, as well as colleagues from Egypt, Jordan and Turkey. As the vicar intoned the consecration, Kell wondered, in the layers of secrecy that formed around a spy like scabs, what sin Wallinger had committed, what treachery he had uncovered, to bring about his own death? Had he pushed too hard on Syria or Iran? Trip-wired an SVR operation in Istanbul? And why Greece, why Chios? Perhaps the official assumption was correct: mechanical failure was to blame. Yet Kell could not shake the feeling that his friend had been assassinated; it was not beyond the realms of possibility that the plane had been shot down. As Wallinger’s coffin was lowered into the ground, he glanced to the right and saw Amelia wiping away tears. Even Simon Haynes looked cleaned out by grief.

Kell closed his eyes. He found himself, for the first time in months, mouthing a silent prayer. Then he turned from the grave and walked back towards the church, wondering if mourners at an SIS funeral, twenty years hence, would whisper the name ‘Wallinger’ in country churchyards as a short-hand for murder and cover-up.

Less than an hour later, the crowds of mourners had found their way to the Wallinger farm, where a barn near the main house had been prepared for a wake. Trestle tables were laid out with cakes and cheese sandwiches cut into white, crustless triangles. Wine and whisky on standby while two old ladies from the village served tea and Nescafé to the great and the good of the transatlantic intelligence community. Kell was greeted with a mixture of rapture and pity by former colleagues, most of whom were too canny and self-serving to offer their whole-hearted support on the fiasco of Witness X. Others had heard word of his divorce on the Service grapevine and placed consoling hands on Kell’s shoulder, as if he had suffered a bereavement or been diagnosed with an inoperable illness. He didn’t blame them. What else were people supposed to say in such circumstances?

The flowers that had lain on Wallinger’s coffin had been set out at one end of the barn. Kell was standing outside, smoking a cigarette, when he saw Wallinger’s children – his son, Andrew, and his daughter, Rachel – bending over the floral tributes, reading the cards, and sharing a selection of the written messages with one another. Andrew was the younger of the two, now twenty-eight, reportedly earning a living in Moscow as a banker. Kell had not seen Rachel for more than fifteen years, and had been struck by her dignity and grace as she supported her mother at the graveside. Andrew had wept desperately for the father he had lost as Josephine stared into the black grave, frozen in what Kell assumed was a medicated grief. Yet Rachel had maintained an eerie stillness, as if in possession of a secret that guaranteed her peace of mind.

He was grinding out the cigarette, half-listening to a local farmer telling a long-winded anecdote about wind farms, when he saw Rachel bend down and pick up a card attached to a small bunch of flowers on the far side of the barn. She was alone, several metres from Andrew, but Kell had a clear view of her face. He saw Rachel’s dark eyes harden as she read the card, then a flush of anger scald her cheeks.

What she did next astonished him. Leaning down, with a brisk flick of her wrist she skidded the flowers low and hard towards the edge of the barn, where they hit the whitewashed wall with a soundless thud. Rachel then placed the card in her coat pocket and returned to Andrew’s side. No words were exchanged. It was as though she did not want to involve her brother in what she had just seen. Moments later Rachel turned and walked back towards the trestle tables, where she was intercepted by a middle-aged woman wearing a black hat. As far as Kell could tell, nobody else had witnessed what had happened.

The barn had become hot and, after a few minutes, Rachel removed her coat, folding it over the back of a chair. She was continually in conversation with guests who wished to convey their condolences. At one point she burst into laughter and the men in the room, as one, seemed to turn and look at her. Rachel had an in-house reputation for beauty and brains; Kell recalled a couple of male colleagues constructing Christmas party innuendoes about her. Yet she was not as he had imagined she would be; there was something about the dignity of her behaviour, the decisiveness with which she had dispatched the flowers, a sense in which she was fully in control of her emotions and of the environment in which she had found herself, that intrigued Kell.

In time, she had made her way to the far side of the barn. She was at least fifty feet from the coat. Kell, carrying a plate of sandwiches and cake towards the chair, took off his own coat and folded it alongside Rachel’s. At the same time, he reached into her outside pocket and removed the card.

He glanced across the barn. Rachel had not seen him. She was still deep in conversation, her back to the chair. Kell walked quickly outside, crossed the drive and went into the Wallingers’ house. Several people were milling about in the hall, guests looking for bathrooms, staff ferrying food and drink from the kitchen to the barn. Kell avoided them and walked upstairs.

The bathroom door was locked. He needed to find a room where he would not be disturbed. Glimpsing posters of Pearl Jam and Kevin Pietersen in a room further along the corridor, Kell found himself in Andrew’s bedroom. There were framed photographs from his time at Eton above a wooden desk, as well as various caps and sporting mementoes. Kell closed the door behind him. He took the card from his jacket pocket and opened it up.

The inscription was in an Eastern European language that Kell assumed to be Hungarian. The note had been handwritten on a small white card with a blue flower printed in the top right-hand corner.

Szerelmem. Szívem darabokban, mert nem tudok Veled lenni soha már. Olyan fájó a csend amióta elmentél, hogy még hallom a lélegzeted, amikor álmodban néztelek.

Had Rachel been able to understand it? Kell put the card on the bed and took out his iPhone. He photographed the message, left the bedroom and returned to the barn.

With Rachel nowhere to be seen, Kell removed his overcoat from the chair and, by simple sleight of hand, replaced the card in her coat pocket. It had been in his possession for no more than five minutes. When he turned around, he saw that she was coming back into the barn and walking towards her mother. Kell went outside for a cigarette.

Amelia was standing on her own in front of the house, like someone at the end of a party waiting for a cab.

‘What have you been up to?’ she asked.

At first, Kell thought that she had spotted him lifting the card. Then he realized, from Amelia’s expression, that the question was merely a general enquiry about his life.

‘You mean recently? In London?’

‘Yes, recently.’

‘You want an honest answer to that?’

‘Of course.’

‘Fuck all.’

Amelia did not react to the bluntness of the response. Ordinarily she would have smiled or conjured a look of mock disapproval. But her mood was serious, as though she had finally arrived at a solution to a problem that had been troubling her for some time.

‘So you’re not busy for the next few weeks?’

Kell felt a jolt of optimism, his luck about to change. Just ask the question, he thought. Just get me back in the game. He looked out across a valley sketched with dry-stone walls and distant sheep, thinking of the long afternoons he had spent brushing up his Arabic at SOAS, the solo holidays in Lisbon and Beirut, the course he had taken at City Lit in twentieth-century Irish poetry. Filling up the time.

‘I’ve got a job for you,’ she said. ‘Should have mentioned it earlier, but it didn’t seem right before the funeral.’ Kell heard the gravel-crunch of someone approaching them across the drive. He hoped the offer would come before they were cut off, mid-conversation. He didn’t want Amelia changing her mind.

‘What kind of job?’

‘Would you go out to Chios for me? To Turkey? Find out what Paul was up to before he died?’

‘You don’t know what he was up to?’

Amelia shrugged. ‘Not all of it. On a personal level. One never does.’ Kell looked down at the damp ground and conceded the point with a shrug. He had dedicated most of his working life to the task of puncturing privacy, yet what did a person ultimately know about the thoughts and motives of the people who were closest to them? ‘Paul had no operational reason to be in Chios,’ Amelia continued. ‘Josephine thinks he was there on business, Station didn’t know he was going.’

Kell assumed that Amelia suspected what was obvious, given Wallinger’s reputation and track record: that he had been on the island with a woman and that he had been careful to cover his tracks.

‘I’ll tell Ankara you’re coming. Red carpet, access all areas. Istanbul ditto. They’ll open up all the relevant files.’

It was like getting a clean bill of health after a medical scare. Kell had been waiting for such a moment for months.

‘I could do that,’ he said.

‘You’re on full pay, yes? We put you on that after France?’ The question was plainly rhetorical. ‘You’ll have a driver, whatever else you need. I’ll make arrangements for you to have a cover identity while you’re there, should you need it.’

‘Will I need it?’

It was as if Amelia was holding back a vital piece of information. Kell wondered what he was signing up for.

‘Not necessarily,’ she said, though her next remark only confirmed his suspicion that there was something else in play. ‘Just tread carefully around the Yanks.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘You’ll see. Tricky out there at the moment.’

He was struck by the intensity with which Amelia was speaking.

‘What are you not telling me?’ he asked.

‘Just find out what happened,’ she replied quickly, and took his wrist in a gloved hand, squeezing hard at the bone as though to stem the flow of blood from a wound. Amelia’s steady eyes held Kell’s, then flicked back in the direction of the wake, at the mourners in black filing out of the barn. ‘Why was Paul on Chios?’ she said, and there was agony in the question, a powerful woman’s despair that she had been unable to protect a man whom perhaps she still loved. ‘Why did he die?’

For a moment Kell thought that her composure was going to crack. He took Amelia’s arm and squeezed back, the reassurance of a friend. But her strength returned, as quickly as the sudden gust of wind that blew across the farm, and whatever Kell was about to say was cut short.

‘It’s simple,’ she said, with the trace of a resigned smile. ‘Just find out why the hell we’re all here.’

7 (#ulink_9f07c35f-dbf4-5480-b11f-c01dd08a7b41)

Kell had packed his bags, cleared out of his room and cancelled his reservation at L’Enclume within the hour. By seven o’clock he was back in Preston station, changing platforms for an evening train to Euston. Amelia had driven to London with Simon Haynes, having called Athens and Ankara with instructions for Kell’s trip. He bought a tuna sandwich and a packet of crisps on the station concourse, washed them down with two cans of Stella Artois purchased from a catering trolley on the train, and finished The Sense of an Ending. No colleague, no friend from SIS had elected to join him on the journey home. There were spies from five continents scattered throughout the train, buried in books or wives or laptops, but none of them would run the risk of publicly consorting with Witness X.

Kell was home by eleven. He knew why Amelia had chosen him for such an important assignment. After all, there were dozens of capable officers pacing the corridors of Vauxhall Cross, all of whom would have jumped at the chance to get to the bottom of the Wallinger mystery. Yet Kell was one of only two or three trusted lieutenants who knew of Amelia’s long affair with Paul. It was rumoured throughout the Service that ‘C’ had never been faithful to Giles; that she had perhaps been involved in a relationship with an American businessman. But, for most, her links to Wallinger would have been solely professional. Any thorough investigation into his private life would inevitably turn up hard evidence of their relationship. Amelia could not afford to have talk of an affair on the record; she was relying on Kell to be discreet with whatever he found.

Before going to bed he repacked his bags, dug out his Kell passport and emailed the photograph of the Hungarian inscription to an old contact in the National Security Authority, Tamas Metka, who had retired to run a bar in Szolnok. By seven the next morning Kell was in a cab to Gatwick and back in the dreary routine of twenty-first-century flying: the long, agitated queues; the liquids farcically bagged; the shoes and belts pointlessly removed.

Five hours later he was touching down in Athens, cradle of civilization, epicentre of global debt. Kell’s contact was waiting for him in a café inside the departures hall, a first-posting SIS officer instructed by Amelia to provide a cover identity for Chios. The young man – who introduced himself as ‘Adam’ – had evidently been working on the legend throughout the night: his eyes were stiff with sleeplessness and he had a rash, red as an allergy, beneath the stubble on his lower jaw. There was a mug of black coffee on the table in front of him, an open sandwich of indeterminate contents, and a padded envelope with the single letter ‘H’ scribbled on the front. He was wearing a Greenpeace sweatshirt and a black Nike baseball cap so that Kell could more easily identify him.

‘Good flight?’

‘Fine, thanks,’ Kell replied, shaking his hand and sitting down. They exchanged pleasantries for a few minutes before Kell took possession of the envelope. He had already passed through Greek Customs, so there was now less danger of being caught with dual identities.

‘It’s a commercial cover. You’re an insurance investigator with Scottish Widows writing up a preliminary report on the Wallinger crash. Chris Hardwick.’ Adam’s voice was quiet, methodical, well-rehearsed. ‘I’ve got you a room at the Golden Sands hotel in Karfas, about ten minutes south of Chios Town. The Chandris was full.’

‘The Chandris?’

‘It’s where everybody stays if they come to the island on business. Best hotel in town.’

‘You think Wallinger may have stayed there under a pseudonym?’

‘It’s possible, sir.’

Kell hadn’t been called ‘sir’ by a colleague in over a year. He had lost sight of his own status, allowed himself to forget the considerable achievements of his long career. Adam was probably no older than twenty-six or twenty-seven. Meeting an officer of Kell’s pedigree was most likely a significant moment to him. He would have wanted to make a good impression, particularly given Kell’s links to ‘C’.

‘I’ve arranged for you to pick up a car at the airport. It’s booked for three days. The Europcar desk is just outside the terminal. There’s a couple of credit cards in Hardwick’s name, the usual pin number, a passport of course, driving licence, some business cards. I’m afraid the only photograph we had of you on file looks a bit out of date, sir.’

Kell didn’t take offence. He knew the picture. Taken in a windowless room at Vauxhall Cross on 9 September 2001. His hair cut shorter, his temples less greyed, his life about to change. Every spy on the planet had aged at least twenty years since then.

‘I’m sure it’ll be fine,’ he said.

Adam looked up at the ceiling and blinked hard, as though trying to remember the last in a sequence of points from a mental checklist.

‘The air traffic control officer who was on duty the afternoon of Mr Wallinger’s flight can meet you tonight at your hotel.’

‘Time?’

‘I said seven.’

‘That’s good. I want to move quickly on this. Thank you.’

Kell watched as Adam absorbed his gratitude with a wordless nod. I remember being you, Kell thought. I remember what it was like at the beginning. With a pang of nostalgia, he pictured Adam’s life in Athens: the vast Foreign Office apartment; the nightclub memberships; the beautiful local girls in thrall to the glamour and expense accounts of the diplomatic life. A young man with a whole career ahead of him, in one of the great cities of the world. Kell put the envelope in his carry-on bag and stood up from the table. Adam accompanied him as far as a nearby duty-free shop, where they parted company. Kell bought a bottle of Macallan and a carton of Winston Lights for Chios and was soon airborne again above the shimmering Mediterranean, checking through the emails and texts that had collected on his iPhone before take-off.

Metka had already sent through a translation of the message seen by Rachel.

My dear Tom

It is always good to hear from you and I am of course happy to help.

So what happened to you? You took up poetry? Writing Magyar love sonnets? Maybe Claire finally had the sense to leave you and you fell in love with a girl from Budapest?

Here is what the poem says – please excuse me if my translation is not as ‘pretty’ as your original:

My darling. I cannot be with you today, of all days, and so my heart is broken. Silence has never been this desperate. You are asleep, but I can still hear you breathing.

It is really very moving. Very sad. I wonder who wrote it? I would like to meet them.

Of course if you are ever here, Tom, we must meet. I hope you are satisfied in your life. You are always welcome in Szolnok. These days I very rarely come to London.

With kind regards

Tamas

Kell powered down the phone and looked out of the window at the wisps of motionless cloud. What Rachel had reacted to so strongly was obvious enough: a message from one of Wallinger’s grieving lovers. But had Rachel understood the Hungarian or recognized the woman’s handwriting? He could not know.

The plane landed at a small, functional, single-runway airport on the eastern shore of Chios. Kell identified the air traffic control tower, saw a bearded engineer on the tarmac tending to a punctured Land Cruiser, and took photographs of a helicopter and a corporate jet parked either side of an Olympic Air Q400. Wallinger would have taken off only a few hundred metres away, then banked east towards Izmir. The Cessna had entered Turkish airspace in less than five minutes, crashing into the mountains south-west of Kütahya perhaps an hour later.

The island’s taxi drivers were on strike so Kell was glad of the hire car, which he drove a few miles south to Karfas along a quiet road lined with citrus groves and crumbling, walled estates. The Golden Sands was a tourist hotel located in the centre of a kilometre-long beach with views across the Chios Strait to Turkey. Kell unpacked, took a shower, then dressed in a fresh set of clothes. As he waited in the bar for his meeting, nursing a bottle of Efes lager and an overwhelming desire to smoke indoors, he reflected on how quickly his personal circumstances had changed. Less than twenty-four hours earlier, he had been eating a tuna sandwich on a crowded train from Preston. Now he was alone on a Greek island, masquerading as an insurance investigator, in the bar of an off-peak tourist hotel. You’re back in the game, he told himself. This is what you wanted. But the buzz had gone. He remembered the feeling of landing in Nice almost two years earlier, instructed by the high priests at Vauxhall Cross to find Amelia at any cost. On that occasion, the rhythms and tricks of his trade had come back to him like muscle memory. This time, however, all that Kell felt was a sense of dread that he would uncover the truth about his friend’s death. No pilot error. No engine failure. Just conspiracy and cover-up. Just murder.

Mr Andonis Makris of the Hellenic Civil Aviation Authority was a thick-set islander of about fifty who spoke impeccable, if over-elaborate English and smelled strongly of eau de cologne. Kell presented him with Chris Hardwick’s business card, agreed that Chios was indeed very beautiful, particularly at this time of year, and thanked Makris for agreeing to meet him at such short notice.

‘Your assistant in the Edinburgh office told me that time was a factor,’ Makris reassured him. He was wearing a dark blue, pin-striped suit and a white shirt without a tie. Self-assured to the point of arrogance, he gave the impression of a man who had, some years earlier, achieved personal satisfaction in almost every area of his life. ‘I am keen to assist you after such a tragedy. Many people on the island were shocked by the news of Mr Wallinger’s death. I am sure his family and colleagues are as keen as we are to find out what happened as soon as is possible in human terms.’

It was obvious from his demeanour that Makris bore no sense of personal responsibility for the crash. Kell assumed that he would want to take the opportunity to shift the blame for the British diplomat’s demise on to the shoulders of Turkish air traffic control as quickly as possible.

‘Did you meet Mr Wallinger personally?’

Makris was taking a sip of white wine and was halted by the question. He swallowed in his own good time and dabbed his mouth carefully with a paper napkin before responding.

‘No.’ The voice was even in tone, a trace of American in the accent. ‘The flight plan had been filed before I arrived on my shift. I spoke to the pilot – to Mr Paul Wallinger – on the radio as he checked his instruments, taxied to the runway and prepared for take-off.’

‘He sounded normal?’

‘What does “normal” mean, please?’

‘Was he agitated? Drunk? Did he sound tense?’

Makris reacted as though Kell had impugned his integrity.

‘Drunk? Of course not. If I sense that a pilot is any of these things, I will prevent him from flying. Of course.’

‘Of course.’ Kell had never had much time for thin-skinned bureaucrats and couldn’t be bothered to summon an apology for whatever offence his remark might have caused. ‘You can understand why I have to ask. In order to complete a full report on the accident, Scottish Widows needs to know everything …’

As though he had already grown tired of listening, Makris leaned down, picked up a slim briefcase and set it on the table. Kell was still speaking as two thick thumbs operated the sliding locks. The catches popped, the lid sprang open, and Makris’s face was momentarily obscured from view.

‘I have the flight plan here, Mr Hardwick. I made a copy for you.’

‘That was very thoughtful.’

Makris lowered the lid, passing Kell a one-page document covered in hieroglyphs of impenetrable Greek. There were boxes where Wallinger had scrawled his personal details, though no address on the island appeared to have been provided.

‘The flight plan was to take the Cessna over Aignoussa, then east into Turkey. It is customary for Çeşme or Izmir to take immediate responsibility for aircraft entering Turkish airspace.’

‘This is what happened?’

Makris nodded gravely. ‘This is what happened. The pilot told us he was leaving our circuit and then changed radio frequency. At this point, Mr Wallinger was no longer our responsibility.’

‘Do you know where he was staying on Chios?’

Makris directed his eyes towards the flight plan. ‘Does it not say?’

Kell turned the sheet of paper around and held it up for inspection. ‘Hard to tell,’ he said.

Makris pursed his lips, as if to imply that Chris Hardwick had caused secondary offence by his failure to read and understand modern Greek. He took back the flight plan, studied it carefully, and was obliged to admit that no address had been given.

‘There seems to be only Mr Wallinger’s residence in Ankara,’ he conceded. Clearly, this was a minor breach in aeronautical protocol. Kell suspected that, first thing in the morning, Makris would hunt down a junior colleague at the airport and take significant pleasure in reprimanding him for the oversight. ‘But there is a telephone number,’ he said, as if to compensate for the clerical error.

‘A telephone number on Chios?’

Makris did not need to look back at the code. ‘Yes.’

According to a preliminary report sent to Amelia the day before the funeral, Wallinger had used his own logbook and JAR licence to hire the Cessna in Turkey, his own passport to enter Ankara, but had then left no trace of his movements once he arrived on Chios. His mobile phone had been switched off for long periods during his stay and there was no activity on any Wallinger credit card, nor on his four registered SIS legends. He had effectively spent a week on Chios as a ghost. Kell assumed that Wallinger had been with a woman, and was trying to conceal his whereabouts from both Josephine and Amelia. Yet the lengths he had gone to suggested that it was equally plausible he had been making contact with an agent.

‘Do you recognize the number?’

‘Do I recognize it?’ Makris’s reply was effortlessly condescending. ‘No.’

‘And have you heard anything about what Mr Wallinger was doing on Chios? Why he was visiting the island? Any rumours around town, newspaper reports?’

Kell accepted that his questions were what is known in the trade as a ‘trawl’, but it was nevertheless important to ask them. It did not surprise him in the least when Makris suggested with a light cough that Mr Hardwick was exceeding his brief.