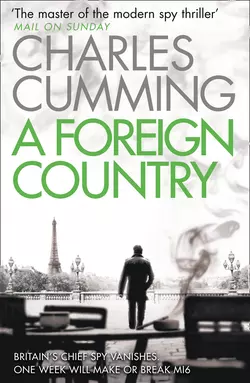

A Foreign Country

Charles Cumming

Winner of the CWA Ian Fleming Steel Dagger 2012 for Best Thriller of the Year. Selected by the Sunday Times and the Guardian as Best Thriller. Perfect for fans of John le Carré, a gripping and suspenseful spy thriller from ‘the master of the modern spy thriller’ (Mail on Sunday) WITH AN EXCLUSIVE AFTERWORD BY THE AUTHOR.Six weeks before she is due to become the first female head of MI6, Amelia Levene disappears without a trace.Disgraced ex-agent Thomas Kell is brought in from the cold with orders to find her – quickly and quietly. The mission offers Kell a way back into the secret world, the only life he’s ever known.Tracking her through France and North Africa, Kell embarks on a dangerous voyage, shadowed by foreign intelligence services. This far from home soil, the rules of the game are entirely different – and the consequences worse than anyone imagines…

CHARLES CUMMING

A Foreign Country

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2012

Copyright © Charles Cumming 2012

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Josephine Pugh/Arcangel Images (cityscape); Henry Steadman (foreground and figure, right); SuperStock (bench, seated man); Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (all other images)

A Colder War extract © Charles Cumming 2013

Charles Cumming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Extract from The Spirit Level copyright © Seamus Heaney

Published in Great Britain by Faber and Faber 2001

Reproduced by permission of Faber and Faber

Extract from The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley © 1953 Hamish Hamilton reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd

Extract from Ashenden by W. Somerset Maugham © 1928 William Heinemann reproduced by kind permission of A P Watt on behalf of the Royal Literary Fund

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © March 2012 ISBN: 9780007346448

Version: 2016-05-03

Dedication

For Carolyn Hanbury

Epigraph

‘There’s just one thing I think you ought to know before you take on this job … If you do well you’ll get no thanks and if you get into trouble you’ll get no help. Does that suit you?’

‘Perfectly.’

‘Then I’ll wish you good afternoon.’

W. Somerset Maugham, Ashenden

‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.’

L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between

Contents

Cover (#u3f26131b-fae9-57b1-9a47-42e1cc5132b6)

Title Page (#uccbd309c-1e08-5090-b820-2efc4fe981e3)

Copyright (#u7ed6d7a3-3980-52ad-8997-a4f6250fffac)

Dedication (#u882decf8-138c-56d6-a25d-c252bdd450de)

Epigraph (#u9e0cc136-9a8a-522b-9c03-bf3326ac7675)

Tunisia, 1978 (#u2f792197-9b7c-5375-a039-cceab2d71d72)

Chapter 1 (#uf1404e1d-a9e8-557a-bd78-04702f3554ec)

The Present Day (#u95869d79-814b-5f14-8241-a0786f9381e8)

Chapter 2 (#u09442355-8d76-5988-8ee3-0cdcd8d7a3cc)

Chapter 3 (#ub098089a-a295-5c65-a02a-846f42616d37)

Chapter 4 (#u715965b8-a2be-5f55-8592-5a4195f3fe06)

Chapter 5 (#u2835797a-4cb9-5949-9d5d-025240c55e71)

Chapter 6 (#u98232d4b-54c1-5ad7-9131-c0c9bd1ed471)

Chapter 7 (#u64765afe-e6f9-533a-8b48-b994448ccf87)

Chapter 8 (#u40ea5ab0-fa51-505f-9c2b-4e97a8a53177)

Chapter 9 (#u5c5e396d-581f-59c1-a3c1-6ad4ad5222b6)

Chapter 10 (#u1d305842-a660-5084-bd6e-45560de90ca2)

Chapter 11 (#uc01a4e72-7e3f-5e3f-82d5-b7450e0948ef)

Chapter 12 (#u2ff19ca6-2d59-5187-9502-8d0263e53f08)

Chapter 13 (#u8d920a3f-09fa-5e63-a3af-d051f04e4409)

Chapter 14 (#ufc67a3ff-c9fd-51dc-8a2e-f80379df6ae2)

Chapter 15 (#u227d79ab-0404-53f9-a64e-af60633e13a0)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 70 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 71 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 72 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 73 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 74 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 75 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 76 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 77 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 78 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 79 (#litres_trial_promo)

Beaune, Three Weeks Later (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 80 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Background to A Foreign Country (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Charles Cumming (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Tunisia, 1978

1

Jean-Marc Daumal awoke to the din of the call to prayer and to the sound of his children weeping. It was just after seven o’clock on an airless Tunisian morning. For an instant, as he adjusted his eyes to the sunlight, Daumal was oblivious to the wretchedness of his situation; then the memory of it took him like a shortness of breath. He almost cried out in despair, staring up at the cracked, whitewashed ceiling, a married man of forty-one at the mercy of a broken heart.

Amelia Weldon had been gone for six days. Gone without warning, gone without reason, gone without leaving a note. One moment she had been caring for his children at the villa – preparing their supper, reading them a bedtime story – the next she had disappeared. At dawn on Saturday, Jean-Marc’s wife, Celine, had found the au pair’s bedroom stripped of its belongings, Amelia’s suitcases taken from the cupboard, her photographs and posters removed from the walls. The family safe in the utility room was locked, but Amelia’s passport, and a necklace that she had placed there for safekeeping, were both missing. There was no record at Port de la Goulette of a twenty-year-old British woman matching Amelia’s description boarding a ferry for Europe, nor any airline out of Tunis with a passenger listing for ‘Amelia Weldon’. No hotel or hostel in the city had a guest registered under her name and the few fresh-faced students and ex-pats with whom she had socialized in Tunis appeared to know nothing of her whereabouts. Presenting himself as a concerned employer, Jean-Marc had made enquiries at the British Embassy, telexed the agency in Paris that had arranged Amelia’s employment and telephoned her brother in Oxford. Nobody, it seemed, could unravel the enigma of her disappearance. Jean-Marc’s only solace lay in the fact that her body had not been discovered in some back alley of Tunis or Carthage; that she had not been admitted to hospital suffering from an illness, which might have taken her from him for ever. He was otherwise utterly bereft. The woman who had brought upon him the exquisite torture of infatuation had vanished as completely as an echo in the night.

The children’s crying continued. Jean-Marc pulled back the single white sheet covering his body and sat up on the bed, massaging an ache in the small of his back. He heard Celine saying: ‘I am telling you for the last time, Thibaud, you are not watching cartoons until you finish your breakfast’ and it took all of his strength not to rise from the bed, to stride into the kitchen and, in his fury, to smack his son through the thin shorts of his Asterix pyjamas. Instead, Daumal drank from a half-empty glass of water on the bedside table, opened the curtains and stood on the first-floor balcony, gazing out over the rooftops of La Marsa. A tanker was moving west to east across the horizon, two days from Suez. Had Amelia left by private boat? Guttmann, he knew, kept a yacht out at Hammamet. The rich American Jew with his contacts and his privilege, the rumours of links to the MOSSAD. Daumal had seen how Guttmann had looked at Amelia; a man who had never wanted for anything in his life desired her as his prize. Had he taken her from him? There was no evidence to support his baseless jealousy, only the cuckold’s fear of humiliation. Numb from lack of sleep, Daumal settled on a plastic chair on the balcony, a smell of baking bread rising up from a neighbouring garden. Two metres away, close to the window, he spotted a half-finished packet of Mars Légère and lit one with a steady hand, coughing on the first lungful of smoke.

Footsteps in the bedroom. The children had stopped crying. Celine appeared at the balcony door and said: ‘You’re awake,’ in a tone of voice that managed to harden his heart against her still further. He knew that his wife blamed him for what had happened. But she did not know the truth. Had she guessed, she might even have comforted him; her own father, after all, had consorted with dozens of women during his married life. He wondered why Celine had not simply fired Amelia. That, at least, would have saved him from this season of pain. It was as though she wanted to torment him by keeping her in the house.

‘I’m awake,’ he replied, although Celine was long gone, locked in the bathroom under her ritual cold shower, scrubbing the child-altered body that was now repulsive to him. Jean-Marc stubbed out his cigarette, returned to the bedroom, found his dressing-gown discarded on the floor and walked downstairs to the kitchen.

Fatima, one of two maids assigned to the Daumal residence as part of the ex-pat package offered by his employers in France, was putting on an apron. Jean-Marc ignored her and, finding a percolator of coffee on the stove, prepared himself a café au lait. Thibaud and Lola were giggling with one another in an adjoining room, but he did not wish to see them. Instead he sat in his office, the door closed, sipping from the bowl of coffee. Every room, every smell, every idiosyncrasy of the villa held for him a memory of Amelia. It was in this office that they had first kissed. It was at the base of those oleander trees at the rear of the property, visible now through the window, that they had first made love in the dead of night, while Celine slept obliviously indoors. Later, Jean-Marc would take appalling risks, slipping away from his bedroom at two or three o’clock in the morning to be with Amelia, to hold her, to swallow her, to touch and manipulate a body that was so intoxicating to him that he actually laughed at the memory of it. And then he heard himself entertaining such thoughts and knew that he was little more than a romantic, self-pitying fool. So many times he had been on the brink of confessing, of telling Celine every secret of the affair: the rooms that he and Amelia had taken in hotels in Tunis; the five April days that they had spent together in Sfax while his wife had been in Beaune with the children. Jean-Marc knew, as he had always known, that he enjoyed deceiving Celine; it was a form of revenge for all the stillness and ennui of their marriage. The lying kept him sane. Amelia had understood that. Perhaps that was what had bound them together – a shared aptitude for deceit. He had been astonished at her ability to finesse their indiscretions, to cover her tracks so that Celine had no suspicion of what was going on. There were the mischievous lies at breakfast – ‘Thank you, yes, I slept very well’ – combined with a studied indifference towards Jean-Marc whenever the two lovers found themselves in Celine’s company. It was Amelia who had suggested that he pay for their hotel rooms in cash, to avoid any dubious transactions appearing on Jean-Marc’s bank statements. It was Amelia who had stopped wearing perfume, so that the scent of Hermès Calèche would not be carried back to the marital bed. There was no question in Jean-Marc’s mind that she had derived a deep satisfaction from these clandestine games.

The telephone rang. It was rare for anybody to call the house before eight o’clock in the morning; Jean-Marc was certain that Amelia was trying to contact him. He picked up the receiver and said: ‘Oui?’ in near-desperation.

A woman with an American accent replied: ‘John Mark?’

It was Guttmann’s wife. The WASP heiress, her father a senator, family money stinking all the way back to the Mayflower.

‘Joan?’

‘That’s right. Have I called at a bad moment?’

He had no time to lament her blithe assumption that all conversations between them should be conducted in English. Neither Joan nor her husband had made any attempt to learn even rudimentary French, only Arabic.

‘No, it is not a bad time. I was just on my way to work.’ He assumed that Joan wanted to arrange to spend the day at the beach with his children. ‘Do you want to speak to Celine?’

A pause. Some of the customary energy went out of Joan’s voice and her mood became businesslike, even sombre.

‘Actually, John Mark, I wanted to speak with you.’

‘With me?’

‘It’s about Amelia.’

Joan knew. She had found out about the affair. Was she going to expose him?

‘What about her?’ His tone of voice had become hostile.

‘She has asked me to convey a message to you.’

‘You’ve seen her?’

It was like hearing that a relative, assumed dead, was alive and well. He was certain now that she would come back to him.

‘I have seen her,’ Joan replied. ‘She’s worried about you.’

Daumal would have fallen on this expression of devotion like a dog snatching at a bone, had it not been necessary to sustain the lie.

‘Well, yes, Celine and the children have been very concerned. One moment Amelia was here with them, the next she was gone …’

‘No. Not Celine. Not the children. She’s worried about you.’

He felt the hope rushing out of him, a door slammed by a sudden wind.

‘About me? I don’t understand.’

Another careful pause. Joan and Amelia had always been close. As Guttmann had entrapped her in charm and money, Joan had played the caring older sister, a role model of elegance and sophistication to which Amelia might one day aspire.

‘I think you do understand, John Mark.’

The game was up. The affair had been revealed. Everybody knew that Jean-Marc Daumal had fallen hopelessly and ridiculously in love with a twenty-year-old au pair. He would be a laughing stock in the ex-patriot community.

‘I wanted to catch you before you went to work. I wanted to reassure you that nobody knows about this. I have not spoken to David, nor do I intend to say anything to Celine.’

‘Thank you,’ Jean-Marc replied quietly.

‘Amelia has left Tunisia. Last night, as a matter of fact. She’s going to go travelling for a while. She wanted me to tell you how sorry she is for the way things worked out. She never intended to hurt you or to abandon your family in the way that she did. She cares for you very deeply. It all just got too much for her, you know? Her heart was confused. Am I making sense, John Mark?’

‘You are making sense.’

‘So perhaps you might tell Celine that this was Amelia on the phone. Calling from the airport. Tell your children that she won’t be coming back.’

‘I will do that.’

‘I think it’s best, don’t you? I think it’s best if you forget all about her.’

The Present Day

2

Philippe and Jeannine Malot, of 79 Rue Pelleport, Paris, had been planning their dream holiday in Egypt for more than a year. Philippe, who had recently retired, had set aside a budget of three thousand euros and found an airline that was prepared to fly them to Cairo (albeit at six o’clock in the morning) for less than the price of a return taxi to Charles de Gaulle airport. They had researched the best hotels in Cairo and Luxor on the Internet and secured an over-60s discount at a luxury resort in Sharm-el-Sheikh, where they planned to relax for the final five days of their journey.

The Malots had arrived in Cairo on a humid summer afternoon, making love almost as soon as they had closed the door of their hotel room. Jeannine had then set about unpacking while Philippe remained in bed reading Naguib Mahfouz’s Akhénaton le Renégat, a novel that he was not altogether enjoying. After a short walk around the local neighbourhood, they had eaten dinner in one of the hotel’s three restaurants and fallen asleep before midnight to the muffled sounds of Cairene traffic.

Three enjoyable, if exhausting days, followed. Though she had developed a minor stomach complaint, Jeannine managed five hours of wide-eyed browsing in the Egyptian Museum, where she declared herself ‘awestruck’ by the treasures of Tutankhamun. On the second morning of their trip, the Malots had set off by taxi shortly after breakfast and were astonished – as all first-time visitors were – to find the Pyramids looming into view no more than a few hundred metres from a nondescript residential suburb at the edge of the city. Hounded by trinket-sellers and under-qualified guides, they had completed a full circuit of the area within two hours and asked a shaven-headed German tourist to take their photograph in front of the Sphinx. Jeannine was keen to enter the Pyramid at Cheops, but went alone, because Philippe suffered from a mild claustrophobia and had been warned by a colleague at work that the interior was both cramped and stiflingly hot. In a mood of jubilation at having finally witnessed a phenomenon that had enthralled her since childhood, Jeannine paid an Egyptian man the equivalent of fifteen euros for a brief ride on a camel. It had moaned throughout and smelled strongly of diesel. She had then accidentally deleted the picture of her husband astride the beast while attempting to organize the pictures on their digital camera at lunch the following day.

On the recommendation of an article in a French style magazine, they had travelled to Luxor by overnight train and booked a room at the Winter Palace, albeit in the Pavilion, a four-star annexed development added to the original colonial hotel. An enterprising tourism company offered donkey rides to the Valley of the Kings that left Luxor at five o’clock in the morning. The Malots had duly signed up, witnessing a dramatic sunrise over the Temple at Hatshepsut just after six a.m. They had then spent what they later agreed had been the best day of their holiday travelling out to the temples at Dendara and Abydos. On their final afternoon in Luxor, Philippe and Jeannine had taken a taxi to the Temple at Karnak and stayed until the evening to witness the famous Sound and Light show. Philippe had fallen asleep within ten minutes.

By Tuesday they were in Sharm-el-Sheikh, on the Sinai Peninsula. Their hotel boasted three swimming pools, a hairdressing salon, two cocktail bars, nine tennis courts and enough security to deter an army of Islamist fanatics. On that first evening, the Malots had decided to go for a short walk along the beach. Though their hotel was at full occupancy, no other tourists were visible in the moonlight as they made their way from the concrete walkway at the perimeter of the hotel down on to the still-warm sand.

It was afterwards estimated that they had been attacked by at least three men, each armed with knives and metal poles. Jeannine’s necklace had been torn away, scattering pearls on to the sand, and her gold wedding ring removed from her finger. Philippe had had a noose placed around his neck and been jerked upright as a second assailant sliced through his throat and stabbed him repeatedly in the chest and legs. He had bled to death within a few minutes. A torn bed sheet that had been stuffed into her mouth had muffled Jeannine’s screams. Her own throat was also slashed, her arms heavily bruised, her stomach and hips struck repeatedly by a metal pole.

A young Canadian couple, honeymooning at a neighbouring hotel, had noticed the commotion and heard Madame Malot’s stifled cries, but could not see what was happening in the light of the waning moon. By the time they got there, the men who had attacked and murdered the elderly French couple had vanished into the night, leaving a scene of devastation that the Egyptian authorities quickly dismissed as a random act of violence, perpetrated by outsiders, which was ‘highly unlikely ever to happen again’.

3

Taking someone in the street is as easy as lighting a cigarette, they had told him, and as Akim Errachidi waited in the van, he knew that he had the balls to pull it off.

It was a Monday night in late July. The target had been given a nickname – HOLST – and its movements monitored for fourteen days. Phone, email, bedroom, car: the team had everything covered. Akim had to hand it to the guys in charge – they were thorough and determined; they had thought through every detail. He was dealing with pros now and, yes, you really could tell the difference.

Beside him, in the driver’s seat of the van, Slimane Nassah was tapping his fingers in time to some R&B on RFM and talking, in vivid detail, about what he wanted to do to Beyoncé Knowles.

‘What an ass, man. Just give me five minutes with that sweet ass.’ He made the shape of it with his hands, brought it down towards his circling groin. Akim laughed.

‘Turn that shit off,’ said the boss, crouched by the side door and ready to spring. Slimane switched off the radio. ‘HOLST in sight. Thirty seconds.’

It was just as they had said it would be. The dark street, a well-known short-cut, most of Paris in bed. Akim saw the target on the opposite side of the street, about to cross at the postbox.

‘Ten seconds.’ The boss at his very best. ‘Remember, nobody is going to hurt anybody.’

The trick, Akim knew, was to move as quickly as possible, making the minimum amount of noise. In the movies, it was always the opposite way: the smash-and-grab of a screaming, adrenalized SWAT team crashing through walls, lobbing stun grenades, shouldering jet-black assault rifles. Not us, said the boss. We do it quiet and we do it slick. We open the door, we get behind HOLST, we make sure nobody sees.

‘Five seconds.’

On the radio, Akim heard the woman saying ‘Clear’ which meant that there were no civilians within sighting distance of the van.

‘OK. We go.’

There was a kind of choreographed beauty to it. As HOLST strolled past Akim’s door, three things happened simultaneously: Slimane started the engine; Akim stepped out into the street; and the boss slid open the side panel of the van. If the target knew what was happening, there was no indication of it. Akim wrapped his left arm around HOLST’s neck, smothered the gaping mouth with his hand and, with his right arm, lifted the body up into the van. The boss did the rest, grabbing at the legs and pulling them inside. Akim then came in behind them, sliding the door shut, just as he had rehearsed a dozen times. They pushed the prisoner to the floor. He heard the boss say: ‘Go’, as calm and controlled as a man buying a ticket for a train, and Slimane pulled the van out into the street.

The whole thing had taken less than twenty seconds.

4

Thomas Kell woke up in a strange bed, in a strange house, in a city with which he was all too familiar. It was eleven o’clock on an August morning in the eighth month of his enforced retirement from the Secret Intelligence Service. He was a forty-two-year-old man, estranged from his forty-three-year-old wife, with a hangover comparable in range and intensity to the reproduction Jackson Pollock hanging on the wall of his temporary bedroom.

Where the hell was he? Kell had unreliable memories of a fortieth birthday party in Kensington, of a crowded cab to a bar in Dean Street, of a nightclub in the wilds of Hackney – after that, everything was a blank.

He pulled back the duvet. He saw that he had fallen asleep in his clothes. Toys and magazines were piled up in one corner of the room. He climbed to his feet, searched in vain for a glass of water and opened the curtains. His mouth was dry, his head tight as a compress as he adjusted to the light.

It was a grey morning, shiftless and damp. He appeared to be on the first floor of a semi-detached house of indeterminate location in a quiet residential street. A small pink bicycle was secured in the drive by a loop of black cable, thick as a python. A hundred metres away, a learner driver with Jackie’s School of Motoring had stalled midway through a three-point turn. Kell closed the curtains and listened for signs of life in the house. Slowly, like a half-remembered anecdote, fragments of the previous evening began to assemble in his mind. There had been trays of shots: absinthe and tequila. There had been dancing in a low-roofed basement. He had met a large group of Czech foreign students and talked at length about Mad Men and Don Draper. Kell was fairly sure that at a certain point he had shared a cab with an enormous man named Zoltan. Alcoholic blackouts had been a regular feature of his youth, but it had been many years since he had woken up with next to no recollection of a night’s events; twenty years in the secret world had taught him the advantage of being the last man standing.

Kell was looking around for his trousers when his mobile phone began to ring. The number had been withheld.

‘Tom?’

At first, through the fog of his hangover, Kell failed to recognize the voice. Then the familiar cadence came back to him.

‘Jimmy? Christ.’

Jimmy Marquand was a former colleague of Kell’s, now one of the high priests of SIS. His was the last hand Kell had shaken before taking his leave of Vauxhall Cross on a crisp December morning eight months earlier.

‘We have a problem.’

‘No small talk?’ Kell said. ‘Don’t want to know how life is treating me in the private sector?’

‘This is serious, Tom. I’ve walked half a mile to a phone box in Lambeth so the call won’t be scooped. I need your help.’

‘Personal or professional?’ Kell located his trousers beneath a blanket on the back of a chair.

‘We’ve lost the Chief.’

That stopped him. Kell reached out and put a hand against a wall in the bedroom. Suddenly he was as sober and clear-headed as a child.

‘You’ve what?’

‘Vanished. Five days ago. Nobody has any workable idea where the hell she’s gone or what’s happened to her.’

‘She?’ The anti-Rimington brigade within MI6 had long been allergic to the notion of a female Chief. It was almost beyond belief that the all-male inmates at Vauxhall Cross had finally allowed a woman to be appointed to the most prestigious position in British Intelligence. ‘When did that happen?’

‘There’s a lot you don’t know,’ Marquand replied. ‘A lot that’s changed. I can’t say any more if we’re talking like this.’

Then why are we talking at all? Kell thought. Do they want me to come back after everything that happened? Have Kabul and Yassin just been brushed under the carpet? ‘I’m not working for George Truscott,’ he said, saving Marquand the effort of asking the question. ‘I’m not coming back if Haynes still has his hands on the tiller.’

‘Just for this,’ Marquand replied.

‘For nothing.’

It was almost the truth. Then Kell found himself saying: ‘I’m beginning to enjoy having nothing to do,’ which was an outright lie. There was a noise on the other end of the line that might have been the extinguishing of Marquand’s hopes.

‘Tom, it’s important. We need a re-tread, somebody who knows the ropes. You’re the only one we can trust.’

Who was ‘we’? The high priests? The same men who had turfed him out over Kabul? The same men who would happily have sacrificed him to the public inquiry currently assembling its tanks on the SIS lawn?

‘Trust?’ he replied, putting on a shoe.

‘Trust,’ said Marquand. It almost sounded as though he meant it.

Kell went to the window and looked outside, at the pink bicycle, at Jackie’s learner driver, moving through the gears. What did the rest of his day hold? Aspirin and daytime TV. Hair-of-the-dog bloody Marys at the Greyhound Inn. He had spent eight months twiddling his thumbs; that was the truth of his new life in the ‘private sector’. Eight months watching black-and-white matinees on TCM and drinking his pay-off in the pub. Eight months struggling to salvage a marriage that would not be saved.

‘There must be somebody else who can do it,’ he said. He hoped that there was nobody else. He hoped that he was getting back in the game.

‘The new Chief isn’t just anybody,’ Marquand replied. ‘Amelia Levene made “C”. She was due to take over in six weeks.’ He had played his ace. Kell sat down on the bed, pitching slowly forwards. Throwing Amelia into the mix changed everything. ‘That’s why it has to be you, Tom. That’s why we need you to find her. You were the only person at the Office who really knew what made her tick.’ He sugared the pill, in case Kell was still wavering. ‘It’s what you’ve wanted, isn’t it? A second chance? Get this done and the file on Yassin will be closed. That’s coming from the highest levels. Find her and we can bring you in from the cold.’

5

Kell had returned to his bachelor’s bedsit in a near-derelict Fiat Punto driven by a moonlighting Sudanese cab driver who kept a packet of Lockets and a well-thumbed copy of the Koran on the dashboard. Pulling away from the house – which had indeed belonged to a genial, gym-addicted Pole named Zoltan with whom Kell had shared a drunken cab-ride from Hackney – he had recognized the shabby streets of Finsbury Park from a long-ago joint operation with MI5. He tried to remember the exact details of the job: an Irish Republican; a plot to blow up a department store; the convicted man later released under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement. Amelia Levene had been his boss at the time.

Her disappearance was unquestionably the gravest crisis MI6 had faced since the fiasco of WMD. Officers didn’t vanish, simple as that. They didn’t get kidnapped, they didn’t get murdered, they didn’t defect. In particular, they didn’t make a point of going AWOL six weeks before they were due to take over as Chief. If the news of Amelia’s disappearance leaked to the media – Christ, even if it leaked within the walls of Vauxhall Cross – the blowback would be incendiary.

Kell had showered at home, eaten some leftover take-away Lebanese, levelled off his hangover with two codeine and a lukewarm half-litre of Coke. An hour later he was standing underneath a sycamore tree two hundred metres from the Serpentine Gallery, Jimmy Marquand striding towards him with a look on his face like his pension was on the line. He had come direct from Vauxhall Cross, wearing a suit and tie, but without the briefcase that usually accompanied him on official business. He was a slight man, a rangy weekend cyclist, tanned year-round and with a thick mop of lustrous hair that had earned him the nickname ‘Melvyn’ in the corridors of SIS. Kell had to remind himself that he had every right to refuse what Marquand was going to offer. But, of course, that was never going to happen. If Amelia was missing, he had to be the one to find her.

They exchanged a brief handshake and turned north-west in the direction of Kensington Palace.

‘So how is life in the private sector?’ Marquand asked. Humour didn’t always come easily to him, particularly at times of stress. ‘Keeping busy? Behaving?’

Kell wondered why he was making the effort. ‘Something like that,’ he said.

‘Reading all those nineteenth-century novels you promised yourself?’ Marquand sounded like a man speaking words that had been written for him. ‘Tending your garden? Tapping out the memoirs?’

‘The memoirs are finished,’ Kell said. ‘You come out of them very badly.’

‘No more than I deserve.’ Marquand appeared to run out of things to say. Kell knew that his apparent bonhomie was a mask concealing a grave, institutional panic over Amelia’s disappearance. He put him out of his misery.

‘How the fuck did this happen, Jimmy?’

Marquand tried to circumvent the question.

‘Word came through from Number 10 shortly after you left,’ he said. ‘They wanted an Arabist, they wanted a woman. She’d impressed the Prime Minister on the JIC. He finds out we’ve lost her, it’s curtains.’

‘That’s not what I meant.’

‘I know that’s not what you meant.’ Marquand’s reply was terse and he looked away, as though ashamed that the crisis had happened on his watch. ‘Two weeks ago she had a briefing with Haynes, the traditional one-on-one in which the baton gets passed from one Chief to the next. Secrets exchanged, tall tales told, all the things that you and me and the good people of Britain are not supposed to know.’

‘Such as?’

‘You tell me.’

‘What, then? Who shot JR? A fifth plane on 9/11? Give me the facts, Jimmy. What did he tell her? Let’s stop fucking around.’

‘All right, all right.’ Marquand swept back his hair. ‘Sunday morning she announces that she has to go to Paris, for a funeral. Taking a couple of days off. Then, on Wednesday, we get another message. An email. She’s strung out after the funeral and has decided to take some holiday. South of France. No warning, just using up the rest of her allowance before the top job sucks all of her time. A painting course in Nice, something that she’d “always wanted to crack”.’ Kell thought that he caught a vapour of alcohol on Marquand’s breath. It could equally well have been his own. ‘Told us that she’d be back in two weeks, reachable on such-and-such a number at such-and-such a hotel in the event of any emergency.’

‘Then what?’

Marquand was holding his hair in place against the buffeting London wind. He came to a halt. A blue plastic bag cartwheeled beside him across a patch of unmown grass, snagging in a nearby tree. He lowered his voice, as though ashamed by what he was about to say.

‘George sent somebody after her. Off the books.’

‘Now why would he do a thing like that?’

‘He was suspicious that she’d arranged a holiday so soon after the download with Haynes. It seemed unusual.’

Kell knew that George Truscott, as Assistant to the Chief, had been the man lined up to succeed Simon Haynes as ‘C’; as far as most observers were concerned, it was merely a question of the PM waving him through. Truscott would have had the suit made, the furniture fitted, the dye-stamped invitations waiting to go out in the post. But Amelia Levene had stolen his prize. A woman. A second-class citizen in the SIS firmament. His resentment towards her would have been toxic.

‘What’s unusual about taking a holiday at this time of year?’

Kell felt that he knew the answer to his own question. Amelia’s story made no sense. It wasn’t like her to attend a painting course; a woman like that didn’t need a hobby. In all the years that he had known Amelia, she had used her holidays as opportunities for relaxation. Health spas, detox clinics, five-star lodges with salad bars and wall-to-wall masseurs. She had never spoken of a desire to paint. As Marquand contemplated his answer, Kell walked across the stretch of unmown ground, pulled the plastic bag clear of the tree and stuffed it into the back pocket of his jeans.

‘You’re a model citizen, Tom, a model citizen.’ Marquand looked down at his shoes and gave a heavy sigh, as if he was tired of making excuses for the failings of other men. ‘Of course there’s nothing unusual about taking a holiday this time of year. But usually we have more warning. Usually it goes in the diary several months in advance. This looked like a sudden decision, a reaction to something that Haynes had told her.’

‘What was Haynes’s view on that?’

‘He agreed with Truscott. So they asked some friends in Nice to keep an eye on her.’

Again, Kell kept his counsel. Towards the end of his career, he had himself become a victim of the paranoid, near-delusional manoeuvrings of George Truscott, yet he was still privately astonished that the two most senior figures in the Service had green-lit a surveillance operation against one of their own.

‘Who are the friends in Nice? Liaison?’

‘Christ, no. Avoid the Frog at all costs. Re-treads. Ours. Bill Knight and his wife, Barbara. Retired to Menton in ’98. We got them to sign up for the painting course, they saw Amelia arrive on Wednesday afternoon, enjoyed a bit of a chat. Then Bill reported her missing when she failed to turn up three mornings in a row.’

‘What’s unusual about that?’

Marquand frowned. ‘I’m not sure I follow you.’

‘Well, couldn’t Amelia have taken a couple of days off? Got sick?’

‘That’s just it. She didn’t call it in. Barbara rang the hotel, there was no sign of her. We telephoned Amelia’s husband –’

‘– Giles,’ said Kell.

‘Giles, yes, but he hasn’t heard from her since she left Wiltshire. Her mobile is switched off, she’s not responding to emails, there’s been no activity on her credit cards. It’s a total blackout.’

‘What about the police?’

Marquand bounced his caterpillar eyebrows and said: ‘Bof ’ in a cod French accent. ‘They haven’t scraped her off a motorway or found her body floating in the Med, if that’s what you mean.’ He saw Kell’s reaction to this and felt compelled to apologize. ‘Sorry, that was tasteless. I didn’t mean to sound glib. This whole thing is a bloody mystery.’

Kell ran through a list of possible explanations, as arbitrary as they were inexhaustible: Russian or Iranian interference in some aspect of Amelia’s personal affairs; a clandestine arrangement with the Yanks relating to Libya and the Arab Spring; a sudden crisis of faith engendered by something in the meeting with Haynes. In the run-up to Kell’s demise at SIS, Amelia had been knee-deep in Francophone West Africa, which might have aroused interest from the French or Chinese. Islamist involvement was a permanent concern.

‘What about known aliases?’ He felt the dryness of his hangover again, the bluntness of three hours’ sleep. ‘Isn’t it possible she’s running an operation, one that Tweedledum and Tweedledee know nothing about?’

Marquand conceded the possibility of this, but wondered what was so secret that it would require Amelia Levene to disappear without at the very least enlisting the technical support of GCHQ.

‘Look,’ he said. ‘The only people who know about this are Haynes, Truscott and the Knights. Paris Station is still in the dark and it needs to stay that way. This leaks out, the Service will be a laughing stock. God knows where it would end. She’s due to meet the PM formally in two weeks’ time. Obviously that meeting can’t be cancelled without creating a gold-tinted Whitehall shitstorm. Washington finds out we’ve lost our most senior spy, they’ll go ballistic. Haynes wants to find her within the next few days and pretend that none of this happened. She’s due back Monday week.’ Marquand looked quickly to his right, as though reacting to a sudden noise. ‘Look, maybe she’ll just show up. It’ll probably be some smoothie from Paris, a Jean-Pierre or a Xavier with a big cock and a gîte in Aix-en-Provence. You know what Amelia’s like with the boys. Madonna could take notes.’

Kell was surprised to hear Marquand talk of Amelia’s reputation so candidly. Philandering, like alcohol, was almost an Office prerequisite, but it was a male sport, jocular and off the books. In all the years that Kell had known her, Amelia had had no more than three lovers, yet she was spoken of as though she had slept her way through seventy-five per cent of the Civil Service.

‘Why Paris?’

Marquand looked up. ‘She stopped there on the way down to Nice.’

‘My question stands. Why Paris?’

‘She went to the funeral on Tuesday.’

‘Whose funeral?’

‘I have absolutely no idea.’ For a dyed-in-the-wool careerist, Marquand didn’t seem unduly concerned about admitting to gaps in his knowledge. ‘All this has happened very fast, Tom. We haven’t been able to get a name. Giles thinks she went to a crematorium in the Fourteenth. Montparnasse. An old friend from student days.’

‘He didn’t go with her?’

‘She told him he wasn’t wanted.’

‘And Giles does what Giles is told to do.’ Kell knew all too well the mechanics of the Levene marriage; he had studied it closely, as a cautionary tale. Marquand looked as if he was about to laugh but thought better of it.

‘Precisely. Dennis Thatcher syndrome. Husbands should be seen and not heard.’

‘Sounds to me like you need to find out who the friend was.’ Kell was stating the obvious, but Marquand appeared to have run out of road.

‘Do I take that as an indication that you’ll help?’

Kell looked up. The branches of the tree were obscuring a charcoal sky. It was going to rain. He thought of Afghanistan, of the book he was meant to be writing, of the vapid August nights stretching ahead of him at his bachelor’s bedsit in Kensal Rise. He thought about his wife and he thought about Amelia. He was convinced that she was alive and convinced that Marquand was hiding something. How many other re-treads would be sent on her tail?

‘How much is Her Majesty offering?’

‘How much would you need?’ It was somebody else’s cash, so Jimmy Marquand could afford to splash it about. Kell didn’t care about the money, not at all, but didn’t want to appear sloppy by not asking. He plucked a figure out of the damp afternoon sky. ‘A thousand a day. Plus expenses. I’ll need a laptop, encrypted, ditto a mobile and the Stephen Uniacke alias. Decent car waiting for me at Nice airport. If it’s a Peugeot with two doors and a tape deck, I’m coming home.’

‘Sure.’

‘And George Truscott pays my speeding fines. All of them.’

‘Done.’

6

Kell caught a flight out of Heathrow at eight. As he was switching it to ‘Flight Mode’, a text message came through on his mobile phone:

Don’t forget appointment tomorrow. 2pm Finchley. Meet you at the Tube.

Finchley. The death throes of his marriage. An hour with a grim-faced guidance counsellor who offered up platitudes like biscuits on a plate. It occurred to Kell, clicking his seat belt on the aisle, that this was only the second time that he had left London in the eight months since his departure from SIS. In mid-March, Claire had suggested a ‘romantic weekend’ in Brighton – ‘to see if we can be more than ships passing in the night’ – but the hotel had played host to an all-night wedding party, they had slept for only three hours, and by Sunday were lost in a familiar blizzard of recrimination and argument.

A young mother was seated beside him on the plane, a toddler strapped into the window seat. She had come prepared for the battle ahead, producing a bag stuffed with magazines and stickers, sugar-free biscuits and a bottle of water. Every now and again, when the boy fidgeted too much or screamed too loudly, his mother would offer up a knowing smile that was halfway to an apology. Kell tried to reassure her that he couldn’t care less: it was only an hour and a half to Nice and he liked the company of children.

‘Do you have kids of your own?’ she said, the question that should never be asked.

‘No,’ Kell replied, picking up a green plastic figurine that had fallen on the floor. ‘Sadly not.’

The mother was preoccupied throughout the flight and Kell was able to read the notes he had made from Amelia’s classified file without being concerned about wandering eyes: the man in the seat across the aisle was engrossed in a spreadsheet; the woman behind him, over his left shoulder, asleep on an inflatable neck pillow. He knew most of Amelia’s story already; they had swapped secrets during the strange intimacy of a fifteen-year friendship. Her journey into the secret world had begun at a young age. While working in Tunis as an au pair in the late 1970s Amelia had been talent-spotted by Joan Guttmann, a deep-cover officer with the Central Intelligence Agency. Guttmann had brought Amelia to the attention of SIS, which had kept an eye on her at Oxford, making an initial move to recruit soon after she had been awarded a starred First in French and Arabic in the summer of 1983. After a year at MECAS, the so-called ‘School for Spies’ in Lebanon, she had been posted to Egypt in ’85 and to Iraq in ’89. Returning to London in the spring of 1993, Amelia Weldon had met and quickly become engaged to Giles Levene, a fifty-two-year-old bond trader with thirty million in the bank and a personality described by one of Kell’s former colleagues as ‘aggressively soporific’. The file noted, with a passive anti-Semitism of the sort Kell believed had largely died out within SIS, that Levene was considered ‘ambivalent’ on Israel, but that his wife’s ‘attitudes in that area’ should ‘nevertheless be monitored for indications of bias’.

In such a context, Amelia’s rise to power made for fascinating reading. There had been an astonishing amount of sexism directed towards her, particularly in the early phase of her career. In Egypt, for example, she had been overlooked for promotion on the grounds that she was unlikely to remain in the Service ‘beyond child-bearing years’. The position had gone instead to a celebrated Cairo alcoholic with two marriages behind him and a record of producing CX reports lifted from the pages of Al-Ahram. Her fortunes began to shift in Iraq, where she worked under non-official cover as an analyst for a French conglomerate. An Irish passport had kept ‘Ann Wilkes’ in Baghdad for the duration of the first Gulf War, and her access to officials in the Ba’ath party, as well as to prominent figures in the Iraqi military structure, had been lauded both in London and in the United States. Since then, her career had gone from strength to strength: there were postings in Washington and to Kabul, where she had operational control of SIS operations throughout Afghanistan for more than two years following the toppling of the Taliban. In an indication of her ambitions for the Service, she had argued for a more robust British influence in Africa, a stance viewed as prescient by Downing Street in the wake of the Arab Spring, but one that had brought her into conflict with George Truscott, a corporatized bureaucrat with a Cold War mindset who was widely despised by the rank and file within SIS.

Kell closed the notebook. He looked at the child beside him, now sleeping in his mother’s arms, and tried to relish some sense of being back in the game. Yet he felt nothing. For eight months he had been treading water, pretending to himself and to Claire that he had taken a principled stand against the double-think and mendacity of the secret state. It was nonsense, of course; they had turfed him out in disgrace. And when Marquand had come calling, the bagman for Truscott and Haynes, Kell had jumped back aboard like a child at a fairground, relishing the prospect of another ride. He realized that any determination he had felt to prove them wrong, to proclaim his innocence, even to create a new life for himself, had been built on sand. He had nothing but his past to live on, nothing but his skills as a spy.

Somewhere over the southern Alps the cabin lights dimmed like an eye test. The flight was on time. Kell looked out of the starboard window and searched for the glow of Nice. A stewardess strapped herself into a rear-facing seat, checked her face in a compact mirror and flashed him an air-conditioned smile. Kell nodded back, necked two aspirin and the remains of a bottle of water, then sat back as the plane banked over the Mediterranean. The landing earned the captain a round of applause from three drunken Yorkshiremen seated two rows behind him. Kell had no luggage in the hold and had cleared Immigration, on his own passport, by eleven fifteen.

The Knights were in Arrivals. Jimmy Marquand had told him to look out for ‘a British couple in their mid-sixties’, he ‘a denizen of the tanning salon with a dyed moustache’, she ‘a tiny, rather sympathetic bird who’s quick on her feet but permanently in her husband’s shadow’.

The description was near-perfect. Emerging from the customs hall through a set of automatic doors, Kell was confronted by a languid Englishman with a deep suntan, wearing pressed chinos and a button-down cream shirt. A pistachio cashmere jumper was slung over his shoulders and knotted, in the Mediterranean style, across his chest. The moustache was no longer dyed but it looked as though Bill Knight had dedicated at least fifteen minutes of his evening to combing every strand of his thinning white hair. Here was a man who had never quite forgiven himself for growing old.

‘Tom, I assume,’ he said, the voice too loud, the handshake too firm, full lips rolling under his moustache as though life was a wine he was tasting. Kell toyed with the idea of saying: ‘I’d prefer it if you referred to me at all times as Mr Kell,’ but didn’t have the energy to hurt his feelings.

‘And you must be Barbara.’ Behind Knight, lingering in what Claire called ‘the Rain Man position’, was a small lady with half-moon spectacles and a deteriorated posture. Her shy, sliding eye contact managed both to apologize for her husband’s slightly ludicrous demeanour and to establish an immediate professional chemistry that Kell was glad of. Knight, he knew, would do most of the talking, but he would get the most productive information from his wife.

‘We have your car waiting outside,’ she said, as Knight offered to carry his bag. Kell waved away the offer and experienced the unsettling realization that his own mother, had she lived, would now be the same vintage as this diminutive lady with unkempt grey hair, creased clothes and soft, uncomplicated gestures.

‘It’s a luxury saloon,’ said Knight, as if he disapproved of the expense. His voice had a smug, adenoidal quality that had already become irritating. ‘I think you’ll be quite satisfied.’

They walked towards the exit. Kell caught their reflection in a facing window and felt like a wayward son visiting his parents at a retirement complex on the Costa del Sol. It seemed astonishing to him that all that SIS had placed between the disappearance of Amelia Levene and a national scandal were a superannuated spook with a hangover and two borderline geriatric re-treads who hadn’t been in the game since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Perhaps Marquand intended Kell to fail. Was that the plan? Or had the Knights come equipped with a hidden agenda, a plan to thwart Kell before he had even started?

‘It’s this way,’ said Knight, as a young woman, undernourished as a catwalk model, ran through the automatic doors and launched herself into the arms of a leathery lothario only a few years younger than Knight. Kell heard her say: ‘Mon cherie!’ in a Russian accent and noted that she kept her eyes open when she kissed him.

They walked out into the humid French evening across a broad concrete apron that connected the terminal building to a three-storey car park a hundred metres to the east. The airport was gradually shutting down, buses nestled side by side beneath a blackened underpass, one of the drivers asleep at the wheel. A line of late arrivals were queuing for a connection to Monaco, all of them noticeably more chic and composed than the pint-swilling hordes Kell had witnessed at Heathrow airport. Knight paid for the car park, carefully folded the receipt into his wallet for expenses, and led him towards a black Citroën C6 on the upper level.

‘The documents you requested arrived an hour ago and are in an envelope on the passenger seat,’ he said. Kell assumed he was talking about the Uniacke legend, which Marquand had sent ahead by courier so that Kell would not have to carry a false passport through French customs. ‘Be warned,’ Knight continued, tapping his fingers on the back window, as though there was somebody hiding inside. ‘It’s a diesel. I can’t tell you how many friends of ours come out here, rent a car from Hertz or Avis and then ruin their time in France by putting unleaded …’

Barbara put a stop to this.

‘Bill, I’m quite sure Mr Kell is capable of filling up a car at a petrol station.’ In the jaundiced light, it was difficult to see if her husband blushed. Kell remembered a line from Knight’s file, which he had flicked through en route to the airport. ‘Abhors a conversational vacuum. Tendency to talk when he might be wiser keeping his counsel.’

‘That’s OK,’ Kell said. ‘Easy mistake to make.’

The Knights’ vehicle, parked alongside the C6, was a right-hand-drive Mercedes with twenty-year-old British plates and a dent on the front-right panel.

‘An old and somewhat battered Merc,’ Knight explained unnecessarily, as though he was used to the car attracting strange looks. ‘But it does us very well. Once a year Barbara and I are obliged to drive back across the Channel to have an MOT and to update the insurance paperwork, but it’s worth it …’

Kell had heard enough. He slung his bag in the back seat of the Citroën and got down to business.

‘Let’s talk about Amelia Levene,’ he said. The car park was deserted, the ambient noise of occasional planes and passing traffic smothering their conversation. Knight, who had been cut-off mid-sentence, looked suitably attentive. ‘According to London, Mrs Levene went missing several days ago. Did you speak to her during the time she attended the painting course?’

‘Absolutely,’ said Knight, as if Kell was questioning their integrity. ‘Of course.’

‘What can you tell me about Amelia’s mood, her behaviour?’

Barbara made to reply, but Knight interrupted her.

‘Completely normal. Very friendly and enthusiastic. Introduced herself as a retired schoolteacher, widowed. Very little to report at all.’

Kell remembered another line from the Knight file: ‘Not always prepared to go the extra mile. A feeling has developed among colleagues over the years that Bill Knight prefers the quiet life to getting his hands dirty.’

Barbara duly filled in the blanks.

‘Well,’ she said, sensing that Kell wasn’t satisfied by her husband’s answer, ‘Bill and I have disagreed about this. I thought that she looked a little distracted. Didn’t do an awful lot of painting, which seemed odd, given that she was there to learn. Also checked her phone rather a lot for text messages.’ She glanced at Kell and produced a tiny, satisfied smile, like someone who has solved a taxing crossword clue. ‘That struck me as particularly strange. You see, people of her vintage aren’t exactly glued to mobiles in the way that the younger generation are. Wouldn’t you say, Mr Kell?’

‘Call me Tom,’ Kell said. ‘What about friends, acquaintances? Did you see her with anybody? When London asked you to keep an eye on Mrs Levene, did you follow her into Nice? Did she go anywhere in the evenings?’

‘That’s an awful lot of questions all at once,’ said Knight, looking pleased with himself.

‘Answer them one at a time,’ Kell said, and felt an operational adrenalin at last beginning to kick in. There was a sudden gust of wind and Knight did something compensatory with his hair.

‘Well, Barbara and myself aren’t aware that Mrs Levene went anywhere in particular. On Thursday evening, for example, she ate dinner alone at a restaurant on Rue Masséna. I followed her back to her hotel, sat in the Mercedes until midnight, but didn’t see her leave.’

Kell met Knight’s eye. ‘You didn’t think to take a room at the hotel?’

A pause, an awkward back-and-forth glance between husband and wife.

‘What you have to understand, Tom, is that we haven’t had a great deal of time to react to all this.’ Knight, perhaps unconsciously, had taken a step backwards. ‘London asked us simply to sign up for the course, to keep an eye on Mrs Levene, to report anything mysterious. That was all.’

Barbara took over the reins. She was plainly worried that they were giving Kell a poor impression of their abilities.

‘It didn’t sound as though London expected anything to happen,’ she explained. ‘It was almost pitched as though they were asking us to look out for her. And it’s only been – what? – two or three days since we reported Mrs Levene missing.’

‘And you’re convinced that she’s not in Nice, that she’s not simply staying with a friend?’

‘Oh, we’re not convinced of anything,’ Knight replied, which was the most convincing thing he had said since Kell had cleared customs. ‘We did as we were told. Mrs Levene didn’t show her face at the course, we rang it in. Mr Marquand must have smelled a rat and sent for reinforcements.’

Reinforcements. It occurred to Kell that exactly twenty-four hours earlier he was drinking in a crowded bar on Dean Street, singing ‘Happy Birthday’ to a forty-year-old university friend whom he hadn’t seen for fifteen years.

‘London are concerned that there’s been no movement on Amelia’s credit cards,’ he said, ‘no response from her mobile.’

‘Do you think she’s … defected?’ Knight asked, and Kell suppressed a smile. Where to? Moscow? Beijing? Amelia would sooner live in Albania.

‘Unlikely,’ he said. ‘Chiefs of the Service are too high profile. The political repercussions would be seismic. But never say never.’

‘Never say never,’ Barbara muttered.

‘What about her room? Has anybody searched it?’

Knight looked at his shoes. Barbara adjusted her half-moon spectacles. Kell realized why they had never progressed beyond Ops Support in Nairobi.

‘We weren’t under instructions to conduct any kind of search,’ Knight replied.

‘And the people running the painting course? Have you talked to them?’

Knight shook his head, still staring at his shoes like a scolded schoolboy. Kell decided to put them out of their misery.

‘OK, tell you what,’ he said, ‘how far is the Hotel Gillespie?’

Barbara looked worried. ‘It’s on Boulevard Dubouchage. About twenty minutes away.’

‘I’m going to go. You’ve booked a room for me under “Stephen Uniacke”, is that right?’

Knight perked up. ‘That is correct. But wouldn’t you like something to eat? Barbara and I thought that we could take you into Nice, to a little place we both enjoy near the port. It stays open well past …’

‘Later,’ Kell replied. There had been a Cajun wrap at Heathrow, a can of Coke to wash it down. That would see him through until morning. ‘But I need you to do something for me.’

‘Of course,’ Barbara replied.

Kell could see how much she wanted to prolong her return to the spotlight and knew that she might still prove useful to him.

‘Call the Gillespie. Tell them you’ve just landed and need a room. Go to the hotel, but wait outside and make sure you speak to me before you check in.’

Knight looked nonplussed.

‘Is that OK?’ Kell asked him pointedly. If Kell was being paid a thousand a day, chances were that the Knights were on at least half that. In final analysis, they were obliged to do whatever he told them. ‘I’ll need to gain access to the hotel’s computer system. I want all the details from Amelia’s room, arrival and departure times, Internet use and so on. In order to do that, I’ll have to distract whoever works the night shift, get them away from the desk for five or ten minutes. You could be very useful in that context – ordering room service, complaining about a broken tap, pulling an emergency cord in the bathroom. Understood?’

‘Understood,’ Knight replied.

‘Do you have a suitcase or something that will pass for an overnight bag?’

Barbara thought for a moment and said: ‘I think so, yes.’

‘Give me half an hour to check in and then make your way to the hotel.’ He was aware of how quickly he was improvising ideas, old tricks coming back to him all the time; it was as though his brain had been sitting in aspic for eight months. ‘It goes without saying that if you see me in the lobby, we don’t know each other.’

Knight produced a blustery laugh. ‘Of course, Tom.’

‘And keep your phone on.’ Kell climbed into the Citroën. ‘Chances are I’ll need to call you within the hour.’

7

The Citroën sat-nav knew how to negotiate the Nice one-way system and had led Kell to Boulevard Dubouchage within twenty minutes. The Hotel Gillespie was exactly the sort of place that Amelia favoured: modest in size but classy; comfortable but not ostentatious. George Truscott would have booked himself a suite at the Negresco and charged the lot to the British taxpayer.

There was an underground car park three blocks away. Kell looked for a secure place to stow his passport and the contents of his wallet and found a narrow wall cavity in a cracked breeze block about two metres above ground. Marquand had sent ahead full documentation for Stephen Uniacke, including credit cards, a passport, a driving licence, and the general paraphernalia of day-to-day life in England: supermarket loyalty cards; membership of Kew Gardens; breakdown cover for the RAC. There were even faded wallet photographs of Uniacke’s phantom wife and phantom children. Kell discarded the envelope and took a lift up to street level. Uniacke – supposedly a marketing consultant with offices in Reading – had been one of three aliases that Kell had regularly employed during his twenty-two-year career in British Intelligence. Assuming the identity one more time felt as natural to him – indeed, in many ways, as comforting – as putting on an old coat.

The Gillespie was set back from the street by a short, semi-circular access road that allowed vehicles to pull up outside the entrance, depositing passengers and baggage. Kell walked through a pair of automatic doors and climbed a flight of steps into an intimate midnight lobby dotted with black-and-white photographs of Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and other musical legends of yesteryear. He had a deep and incurable aversion to jazz but a fondness for sober, low-lit lobbies with rugs on old wooden floors, decent oil paintings and residents’ bars that tinkled with ice and conversation. A young man in a dark jacket with acne and cropped blond hair was organizing a large bowl of potpourri on the reception desk. The night porter. He greeted Kell with an effortful smile and Kell saw that he looked tired to the point of exhaustion.

‘May I help you, sir?’

Kell put his bag on the ground and explained, in French, that he had reserved a room under the name ‘Uniacke’. He was asked for his identification and a credit card, and obliged to fill in a brief registration form. There was a computer terminal at the desk on which the porter called up Uniacke’s details. The keyboard was below the counter, out of sight, so that it was not possible for Kell to follow the keystrokes of any log-in password.

‘I’ve stayed here before,’ he said, scoping the small office at the back of the reception area where a second computer terminal was visible. There was a can of Coke adjacent to the screen and a large paperback book open on the desk. Kell had been looking for evidence of a CCTV system in the lobby but had not yet seen one. ‘Do you have a record of that on your system?’

It was a prepared question to which he already knew the answer. Nevertheless, when the porter responded, he would have the opportunity to lean over the desk and to look directly at the reservation system in feigned astonishment.

‘Let me have a look, sir,’ the porter duly replied. A downy fur covered his pale, washed-out skin, a zit primed to burst on the chin. ‘No, I don’t think we have a record of that here …’

‘You don’t?’ Kell ramped up his surprise and touched the side of the screen, tilting it towards him so that he could identify the booking software operated by the hotel. It was ‘Opera’, the most widely used reservations system in Europe and one with which Kell was reasonably familiar. Uniacke’s details were laid out on a guest folio that itemized his impending expenses in a series of boxes marked ‘Food’, ‘Accommodation’, ‘Drinks’ and ‘Telephone’. As long as the porter left himself logged in, accessing Amelia’s information would be straightforward. Kell knew that she had been staying in Room 218 and that the tabs on Opera would take him to her personal details in two or three clicks of a mouse.

‘Perhaps it’s under my wife’s name,’ he said, moving his hand back behind the counter. A guest emerged from the bar, nodded at the porter and walked out of the lobby towards a bank of lifts. Kell took a few steps backwards, peered into the bar, and spotted a young couple drinking cognacs at a table in the far corner. A wide-hipped barmaid was picking peanuts off the carpet. The room was otherwise deserted. ‘Never mind,’ he said, turning back to the desk. ‘Could I arrange a wake-up call for the morning? Seven o’clock?’

It was a small detail, but would give the porter the useful impression that Monsieur Uniacke intended to go to sleep as soon as he reached his room.

‘Of course, sir.’

Kell was allocated a room on the third floor and walked up the stairs in order to familiarize himself with the layout of the hotel. On the first-floor landing he saw something that gave him an idea: a cupboard, the door ajar, in which a chambermaid had left a Hoover and various cleaning products. He continued along a short passage, entered his room using his card key, and immediately began to unpack. En route to Heathrow, Marquand had given him a laptop. Kell placed an encrypted 3G modem in a USB port and accessed the SIS server through three password-protected firewalls. There were two miniatures of Johnnie Walker in the mini-bar and he drank them, fifty-fifty with Evian, while he checked his email. Marquand had sent a message with an update on Amelia’s disappearance:

Trust you have arrived safely. No sign of our friend. Peripherals still inactive.

‘Peripherals’ was a reference to Amelia’s credit cards and mobile phone.

Funerals at crematoria in the Paris 14th on applicable days. Look for surnames: Chamson, Lilar, de Vilmorin, Tardieu, Radiguet, Malot, Bourget. Investigating further. Should have specifics within 24.

Crematoria. Trust Marquand to be fastidious with the Latin. Kell sprayed some aftershave under his shirt, switched the SIMs on his mobile so that he could check any private messages from London, and wolfed a tube of Pringles from the mini-bar. He then replaced the Uniacke SIM and dialled the Knights’ number. Barbara picked up. It sounded as though her husband was doing the driving.

‘Mr Kell?’

‘Where are you, Barbara?’

‘We’re just parking around the corner from the hotel. We were a little delayed in traffic.’

‘Did you get the room?’

‘Yes. We rang from the airport.’

‘Who made the call?’

‘I did.’

‘And did you say it was for two people?’

Barbara hesitated before replying, as though she suspected Kell was laying a trap for her. ‘Not specifically, but I think he understood that I was with my husband.’

Kell took the risk. ‘Change of plan,’ he said. ‘I want you to check in alone. I need you to leave Bill on the outside.’

‘I see.’ There was an awkward pause as Barbara absorbed the instruction.

‘I’m going to create a diversion at two o’clock that will require the night porter to go upstairs and fetch a Hoover.’

The line cut out briefly and Barbara said: ‘A what?’

‘A Hoover. A vacuum cleaner. Listen carefully. What I’m going to tell you is important. The Hoover is in a cupboard on the first-floor landing. You’ll be waiting there at two. When the porter comes up, tell him that you’re lost and can’t find your room. Get him to show you where it is. Don’t let him come back to reception. If he insists on doing so, make a fuss. Feign illness, start crying, do whatever you have to do. When you get to the door of your room, ask him to come inside and explain how to work the television. Keep him busy, that’s the main thing. I may need ten minutes if the log-in is down. Ask him questions. You’re a lonely old lady with jet lag. Is that OK? Do you think you can manage that?’

‘It sounds very straightforward,’ Barbara replied, and Kell detected a note of terseness in her voice. He was aware that he was being brusque, and that to describe her as an ‘old lady’ was not, in retrospect, particularly constructive.

‘When you check in, play up the eccentric side of your personality,’ he continued, trying to restore some rapport. ‘Get your papers in a muddle. Ask how to use the card key for your room. Flirt a little bit. The night porter is a young guy, probably speaks English. Try that first before you opt for French. OK?’

It sounded as though Barbara was writing things down. ‘Of course, Tom.’

Kell explained that he would call back at 1.45 a.m. to confirm the plan. In the meantime, she was to check the hotel for any signs of a security guard, maid or member of the kitchen staff who might have remained on the premises. If she saw anybody, she was to alert him immediately.

‘What room are you in?’ Barbara asked him.

‘Three two two. And tell Bill to keep his eye on the entrance. Anybody tries to come in from the street between one fifty-five and two-fifteen, he needs to stall them.’

‘I’ll do that.’

‘Make sure he understands. The last thing I’ll need when I’m sitting in the office is a guest walking through the lobby.’

8

‘I simply don’t understand it. I don’t understand why he doesn’t want me to be involved.’

Bill Knight was slumped over the wheel of the Mercedes, staring down at his beige patent leather shoes, shaking his head as he tried to fathom this latest, and probably final, SIS insult to his operational abilities. A passer-by, gazing through the window, might have assumed that he was weeping.

‘Darling, he does want you to be involved. He just wants you to be on the outside. He needs you to keep an eye on the door.’

‘At two o’clock in the morning? Who comes back to a hotel at two o’clock in the morning? He doesn’t trust me. He doesn’t think I’m up to it. He’s been told that you’re the star. It was ever thus.’

Barbara Knight had mopped and soothed her husband’s fragile ego for almost forty years, through myriad professional humiliations, incessant financial crises, even his own hapless infidelities. She squeezed his clenched fingers as they gripped the handbrake and tried to resolve this latest crisis as best she could.

‘Plenty of people come back to a hotel at two o’clock in the morning, Bill. You’re just too old to remember.’ That was a mistake, reminding him of his age. She tried a different approach. ‘Kell needs to gain control of the reservations system. If somebody comes through the door and sees him behind the desk, they might smell a rat.’

‘Oh balls,’ said Knight. ‘It isn’t possible to get into any half-decent hotel in the world at that hour without first ringing a bell and having someone come down to let you in. Kell is fobbing me off. I’ll be wasting my time out here.’

Right on cue, two guests appeared at the entrance to the Hotel Gillespie, rang the doorbell and waited as the night porter made his way to the bottom of the stairs. It was as though they had been provided by a mischievous god to illustrate Knight’s point. The porter assessed their credentials and allowed them to pass into the lobby. Bill and Barbara Knight, parked fifty metres away, saw the whole thing through the windscreen of their superannuated Mercedes.

‘See?’ he said, with weary triumph.

Barbara was momentarily lost for words.

‘Nevertheless,’ she managed, ‘it’s best if they don’t ring the bell. Why don’t you buy yourself a packet of cigarettes and just loiter outside or something? You could still be very useful, darling.’

Knight felt that he was being hoodwinked. ‘I don’t smoke,’ he said, and Barbara summoned the last of her strength in the face of his petulance.

‘Look, it’s perfectly clear that there’s no role for you in the hotel. Kell wants me to play Miss Marple and make a nuisance of myself. If we go in as husband and wife, I’m automatically less vulnerable. Do you see?’

Knight ignored the question. Barbara finally lost her patience.

‘Fine,’ she said. ‘Perhaps it would be better if you simply went home.’

‘Went home?’ Knight reared up from the wheel and Barbara saw that his eyes were stung with resentment; oddly, it was the same wretched expression that he wore after almost every conversation with their errant thirty-six-year-old son. ‘I’m not going to leave you alone in a hotel with a man we don’t know, working all hours of the night on some crackpot scheme to …’

‘Darling, he’s hardly someone we don’t know …’

‘I don’t like the look of him. I don’t like his manner.’

‘Well, I’m sure the feeling is mutual.’

That was a second mistake. Knight inhaled violently through his nose and turned to stare out of the window. Moments later, he had switched on the engine and was beckoning Barbara to leave, purely by force of his body language.

‘Don’t be cross,’ she said, one hand on the door, the other still on the handbrake. She was desperate to get into the hotel and to check into her room, to fulfil the task that had been given to her. Her husband’s constant neediness was pointless and counter-productive. ‘You know it isn’t personal.’ An overweight man wearing a tracksuit and bright white trainers walked past the Gillespie, turned left along Rue Alberti and disappeared. ‘I’ll be perfectly all right. I’ll call you in less than an hour. Just wait in a café if you’re worried. Tom will probably send me home in a couple of hours.’

‘What café? I’m sixty-two years old, for goodness’ sake. I can’t go and sit in a café.’ Knight continued to stare out of the window. He looked like a jilted lover. ‘In any case, don’t be so ridiculous. I can’t abandon my post. He wants me watching the fucking entrance.’

It began to rain. Barbara shook her head and reached for the door. She didn’t like to hear her husband swearing. On the back seat of the Mercedes was a sausage bag in which the Knights usually ferried bottles and cans to a recycling area in Menton. She had stuffed it with a scrunched-up copy of Nice-Matin, an old hat and a pair of Wellington boots. She picked it up. ‘Just remember that we’ve had a lot of fun in the last few days,’ she said. ‘And that we’re being very well paid.’ Her words appeared to have no visible impact. ‘I’ll ring you as soon as I get to my room, Bill.’ A gentle kiss on the cheek. ‘Promise.’

9

Kell drained the last of the Johnnie Walker and picked up the landline on the bedside table. He dialled ‘0’ for Reception. The night porter answered on the second ring.

‘Oui, bonsoir, Monsieur Uniacke.’

It was now just a question of spinning the story. The wi-fi in his room wasn’t connecting, Kell said. Could Reception check the system? The porter apologized for the inconvenience, dictated a new network key over the phone, and hoped that Monsieur Uniacke would have better luck second time around.

He didn’t. Ten minutes later, Kell picked up the laptop and took a lift down to the ground floor. The lobby was deserted. The two guests who had been drinking cognacs in the bar had gone to bed, their table wiped clean. The lights had been dimmed and there was no sign of the barmaid.

Kell walked towards the reception desk. He had been standing there for several seconds before the night porter, lost in his textbook in the back office, looked up, jerked out of his seat and apologized for ignoring him.

‘Pas de problème,’ Kell replied. It was always advisable to speak to the French in their mother tongue; you earned their confidence and respect that much more quickly. He flipped open the laptop, pointed to the screen and explained that he was still having difficulty connecting. ‘Is there anybody in the hotel who might be able to help?’

‘I’m afraid not, sir. I’m here alone until five o’clock. But you may find that the signal is stronger in the lobby. I can suggest that you take a seat in the bar and try to connect from there.’

Kell looked across at the darkened lounge. The porter seemed to read his mind.

‘It will be easy to turn up the lights. Perhaps you would also like to take something from the bar?’

‘That would be very kind.’

Moments later, the porter had opened a low connecting door into the lobby and disappeared behind the bar. Kell picked up the laptop, quickly moved the bowl of potpourri on the counter six inches to the left, and followed him.