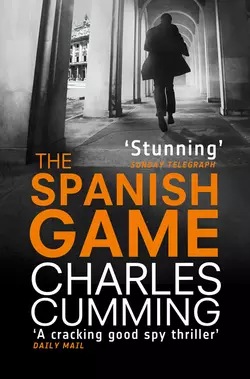

The Spanish Game

Charles Cumming

A vivid and gripping novel from ‘the master of the modern spy thriller’ (Mail on Sunday) which sees Alec Milius coaxed back into the secret world to face the uncontainable danger of 21st century terrorism…For six years, Alec Milius has escaped the past. In Madrid, he has rebuilt his life, but remains in exile and in danger.Slightly older, and much wiser, than the young spy who first impressed MI6, he has kept his fatal attraction to secrets. So when a prominent politician mysteriously disappears, Alec is lured back into the spying game.Only this time he operates without the protection of any official agency – isolated and expendable, with nobody to turn to if things go wrong. And they soon do.But when Alec is confronted with the nightmare of modern terrorism, he is given one last chance for redemption…

Charles Cumming

The Spanish Game

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarpercollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Penguin Books Ltd. 2006

THE SPANISH GAME

Copyright © Charles Cumming 2006.

Extract from The Talented Mr Ripley by Anthony Minghella

(screenplay copyright © The Ant Colony Ltd., 2000)

reproduced by kind permission of Methuen Publishing Ltd.

Charles Cumming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007416936

Ebook Edition © JULY 2011 ISBN: 9780007416929

Version: 2018-09-27

Dedication

For my mother and Simon, my step-father

Epigraph

‘Madrid is a strange place anyway. I do not believe anyone likes it much when he first goes there. It has none of the look that you expect of Spain…Yet when you get to know it, it is the most Spanish of all cities, the best to live in, the finest people, and month in and month out the finest climate. While other big cities are all very representative of the province they are in, they are either Andalucian, Catalan, Basque, Aragonese, or otherwise provincial. It is in Madrid only that you get the essence…It makes you feel very badly, all question of immortality aside, to know that you will have to die and never see it again.’

Ernest Hemingway

Contents

Cover (#ulink_fa5b0dbf-3381-5fea-a7a9-621c78b98b38)

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Map

One

Exile

Two

Baggage

Three

Taxi Driver

Four

The Keeper of the Secrets

Five

Ruy Lopez

Six

The Defence

Seven

Churches

Eight

Another Country

Nine

Arenaza

Ten

Level Three

Eleven

California Dreaming

Twelve

Pillow Talk

Thirteen

Development

Fourteen

Chicote

Fifteen

The Disappeared

Sixteen

Peñagrande

Seventeen

The Lost Weekend

Eighteen

Atocha

Nineteen

Middlegame

Twenty

Dry Cleaning

Twenty-One

Ricken Redux

Twenty-Two

Barajas

Twenty-Three

Bonilla

Twenty-Four

El Cochinillo

Twenty-Five

Our Man in Madrid

Twenty-Six

Sacrifice

Twenty-Seven

Shallow Grave

Twenty-Eight

Dirty War

Twenty-Nine

Taken

Thirty

Out

Thirty-One

Plaza de Colón

Thirty-Two

Black Widow

Thirty-Three

Reina Victoria

Thirty-Four

House of Games

Thirty-Five

La Bufanda

Thirty-Six

Blind Date

Thirty-Seven

The Raven

Thirty-Eight

Columbia

Thirty-Nine

Product

Forty

Line 5

Forty-One

Sleeper

Forty-Two

La Víbora Negra

Forty-Three

Counterplay

Forty-Four

The Vanishing Englishman

Forty-Five

Endgame

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Other Books by Charles Cumming

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

The Spanish Game is a work of fiction inspired by real events. With one or two obvious exceptions, the characters depicted in the novel are products of my imagination. The book has been written with respect for opinions on both sides of the Basque conflict.

The story takes place in Madrid in the first half of 2003, many months before the events of 11 March 2004 which left 192 people dead and more than 1,700 injured. At the time of writing, no evidential link between the perpetrators of the Atocha bombings and Basque terrorist groups has ever been established.

C.C.

London, October 2005

Map

ONE

Exile

The door leading into the hotel is already open and I walk through it into a low, wide lobby. Two South American teenagers are playing Gameboys on a sofa near reception, kicking back in hundred-dollar trainers while Daddy picks up the bill. The older of them swears loudly in Spanish and then catches his brother square on the knot of his shoulder with a dead arm that makes him wince in pain. A passing waiter looks down, shrugs and empties an ashtray at their table. There’s a general atmosphere of listless indifference, of time passing by to no end, the pre-rush lull of late afternoons.

‘Buenas tardes, señor.’

The receptionist is wide shouldered and artificially blonde and I play the part of a tourist, making no effort to speak to her in Spanish.

‘Good afternoon. I have a reservation here today.’

‘The name, sir?’

‘Alec Milius.’

‘Yes, sir.’

She ducks down and taps something into a computer. Then there’s a smile, a little nod of recognition and she writes down my details on a small piece of card.

‘The reservation was made over the internet?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Could I see your passport please, sir?’

Five years ago, almost to the day, I spent my first night in Madrid at this same hotel; a 28-year-old industrial spy on the run from the UK with $189,000 lodged in five separate bank accounts, using three passports and a forged British driving licence for ID. On that occasion I handed a Lithuanian passport issued to me in Paris in August 1997 to the clerk behind the desk. The hotel may have a record of this on their system, so I’m using it again.

‘You are from Vilnius?’ the receptionist asks.

‘My grandfather was born there.’

‘Well, breakfast is between seven thirty and eleven o’clock and you have it included as part of your rate.’ It is as if she has no recollection of having asked the question. ‘Is it just yourself staying with us?’

‘Just myself.’

My luggage consists of a suitcase filled with old newspapers and a leather briefcase containing some toiletries, a laptop computer and two of my three mobile phones. We’re not planning to stay in the room for more than a few hours. A porter is summoned from across the lobby and he escorts me to the lifts at the back of the hotel. He’s short and tanned and genial in the manner of low-salaried employees badly in need of a tip. His English is rudimentary, and it’s tempting to break into Spanish just to make the conversation more lively.

‘This is being your first time in Madrid, yes?’

‘Second, actually. I visited two years ago.’

‘For the bullfights?’

‘On business.’

‘You don’t like the corrida?’

‘It’s not that. I just didn’t have the time.’

The room is situated halfway down a long, Barton Fink corridor on the third floor. The porter uses a credit-card sized pass key to open the door and places my suitcase on the ground. The lights are operated by inserting the key in a narrow horizontal slot outside the bathroom door, although I know from experience that a credit card works just as well; anything narrow enough to trigger the switch will do the trick. The room is a reasonable size, perfect for our needs, but as soon as I am inside I frown and make a show of looking disappointed and the porter duly asks if everything is all right.

‘It’s just that I asked for a room with a view over the square. Could you see at the desk if it would be possible to change?’

Back in 1998, as an overt target conscious of being watched by both American and British intelligence, I ran basic counter-surveillance measures as soon as I arrived at the hotel, searching for microphones and hidden cameras. Five years later, I am either wiser or lazier; the simple, last-minute switch of room negates any need to sweep. The porter has no choice but to return to reception and within ten minutes I have been assigned a new room on the fourth floor with a clear view over Plaza de Santa Ana. After a quick shower I put on a dressing gown, turn down the air conditioning and try to make the room look less functional by folding up the bedspread, placing it in a cupboard and opening the net curtains so that the decent February light can flood in. It’s cold outside, but I stand briefly on the balcony looking out over the square. A neat line of chestnut trees runs east towards the Teatro de España where a young African man is selling counterfeit CDs from a white sheet spread out on the pavement. In the distance I can see the edge of the Parque Retiro and the roofs of the taller buildings on Calle de Alcalá. It’s a typical midwinter afternoon in Madrid: high blue skies, a brisk wind whipping across the square, sunlight on my face. Turning back into the room I pick up one of the mobiles and dial her number from memory.

‘Sofía?’

‘Hola, Alec.’

‘I’m in.’

‘What is the number of the room?’

‘Cuatrocientos ocho. Just walk straight through the lobby. There’s nobody there and they won’t stop you or ask any questions. Keep to the left. The elevators are at the back. Fourth floor.’

‘Is everything OK?’

‘Everything’s OK.’

‘Vale,’ she says. Fine. ‘I’ll be there in an hour.’

TWO

Baggage

Sofía is the wife of another man. We have been seeing each other now for over a year. She is thirty years old, has no children and has been married, unhappily, since 1999. To meet in the Reina Victoria hotel is something that she has always wanted us to do, and with her husband due back in Madrid on an 8 a.m. flight tomorrow, we can stay here until the early hours of the morning.

Sofía knows nothing about Alec Milius, or at least nothing of any hard fact or consequence. She does not know that at the age of twenty-four I was talent-spotted by MI6 in London and placed inside a British oil company with the purpose of befriending two employees of a rival American firm and selling them doctored research data on an oilfield in the Caspian Sea. Katharine and Fortner Simms, both of whom worked for the CIA, became my close friends over a two-year period, a relationship which ended when they discovered that I was working for British intelligence. Sofía is not aware that in the aftermath of the operation my former girlfriend, Kate Allardyce, was murdered in a car accident engineered by the CIA, alongside another man, her new boyfriend, Will Griffin. Nor does she know that in the summer of 1997 I was dismissed by MI5 and MI6 and threatened with prosecution if I revealed anything about my work for the government.

As far as Sofía is concerned, Alec Milius is a typical foot-loose Englishman who turned up in Madrid in the spring of 1998 after working as a financial correspondent for Reuters in London and, latterly, St Petersburg. He has lost touch with the friends he knew from school and university, and both his parents died when he was a teenager. The money they left him allows him to live in an expensive two-bedroom flat in downtown Madrid and drive an Audi A6 for work. The fact that my mother is still alive and that the last five years of my life have been largely funded by the proceeds of industrial espionage is not something that Sofía and I have ever discussed.

What is the truth? That I have blood on my hands? That I walk the streets with knowledge of a British plot against American business concerns that would blow George and Tony’s special relationship out of the water? Sofía does not need to know about that. She has her own lies, her own secrets to conceal. What did Katharine say to me all those years ago? ‘The first thing you should know about people is that you don’t know the first thing about them.’ So we leave it at that. That way we keep things simple.

And yet, and yet…five years of evasion and lies have taken their toll. At a time when my contemporaries are settling down, making their mark, breeding like locusts, I live alone in a foreign city, a man of thirty-three with no friends or roots, drifting, time-biding, waiting for something to happen. I came here exhausted by secrecy, desperate to wipe the slate clean, to be rid of all the half-truths and deceptions that had become the common currency of my life. And now what is left? An adultery. A part-time job working due diligence for a British private bank. A stained conscience. Even a young man lives with the mistakes of his past and regret clings to me like a sweat which I cannot shift.

Above all, there is paranoia: the threat of vengeance, of payback. To escape Katharine and the CIA I have no Spanish bank accounts, no landline phone number at the apartment, two PO boxes, a Frankfurt-registered car, five email addresses, timetables of every airline flying out of Madrid, the numbers of the four phone boxes thirty metres up my street, a rented bedsit in the village of Alcalá de los Gazules within a forty-minute drive of the boat to Tangier. I have moved apartment four times in five years. When I see a tourist’s camera pointed at me outside the Palacio Real, I fear that I am being photographed by an agent of SIS. And when the genial Segovian comes to my flat every three months to read the water meter, I follow him at a distance of no less than two metres to ensure that he has no opportunity to plant a bug. This is a tiring existence. It consumes me.

So there is booze, and a lot of it. Booze to alleviate the guilt, booze to soften the suspicion. Madrid is built for late nights, for bar-crawling into the small hours, and four mornings out of five I wake with a hangover and then drink again to cure it. It was booze that brought Sofía and me together last year, a long evening of caipirinhas at a bar on Calle Moratín and then falling into bed together at 6 a.m. The sex we have is like the sex that everybody has, only heightened by the added frisson of adultery and ultimately rendered meaningless by an absence of love. Ours is not, in other words, a relationship to compare with the one that I had with Kate–and it is probably all the better for that. We know where we stand. We know that one of us is married, and that the other never confides. Try as she might, Sofía will never succeed in drawing me out of my shell. ‘You are closed, Alec,’ she says. ‘Eres muy tuyo.’ An amateur Freudian would say that I have had no serious relationship in eight years as a consequence of my guilt over Kate’s death. We are all amateur Freudians now. And there is perhaps some truth in that. The reality is more mundane; it is simply that I have never met anyone to whom I have wanted to entrust my tawdry secrets, never met anyone whose life was worth destroying for the sake of my security and peace of mind.

Far below, in the square, a busker has started playing alto sax, a tone-deaf cover version of ‘Roxanne’, loud enough for me to have to close the doors of the balcony and switch on the hotel TV. Here’s what’s on: a dubbed Brazilian soap opera starring a middle-aged actress with a bad nose job; a press conference with the government’s interior minister, Félix Maldonado; a Spanish version of the British show Trisha, in which an audience of Franco-era madrileños are staring openmouthed at a quartet of transvestite strippers lined up on stools along a bright orange stage; a re-run on Eurosport of Germany winning the 1990 World Cup; Christina Aguilera saying that she ‘really, really’ respects one of her colleagues ‘as an artist’ and is ‘just waiting for the right script to come along’ a CNN reporter standing on a balcony in Kuwait City being patronizing about ‘ordinary Iraqis’ and BBC World, where the anchorman looks about twenty-five and never fluffs a line. I stick with that, if only for a glimpse of the old country, for low grey skies and the stiff upper lip. At the same time I boot up the laptop and download some emails. There are seventeen in all, spread over four accounts, but only two that are of interest.

From: julianchurch@bankendiom.es

To: alecm@bankendiom.es

Subject: Basque visit

Dear Alec

Re: our conversation the other day. If any situation encapsulates the petty small-mindedness of the Basque problem, it’s the controversy surrounding poor Ainhoa Cantalapiedra, the rather pretty pizza waitress who has won Operación Triunfo. Have you been watching it? Spain’s answer to Fame Academy. The wife and I were addicted.

As you may or may not know, Miss Cantalapiedra is a Basque, which has led to accusations that the result was fixed. The (ex) leader of Batasuna has accused Aznar’s lot of rigging the vote so that a Basque would represent Spain at the Eurovision Song Contest. Have you ever heard such nonsense? There’s a rather good piece about it in today’s El Mundo.

Speaking of the Basque country, would you be available to go to San Sebastián early next week to meet officials in various guises with a view to firming up the current state of affairs? Endiom have a new client, Spanish-based, looking into viability of a car operation, but rather cold feet politically.

Will explain more when I get back this w/e.

All the very best

Julian

I click ‘Reply’:

From: alecm@bankendiom.es

To: julianchurch@bankendiom.es

Subject: Re: Basque visit

Dear Julian

No problem. I’ll give you a call about this at the weekend. I’m off to the cinema now and then to dinner with friends.

I didn’t watch Operación Triunfo. Would rather cook a five-course dinner for Osama bin Laden–with wines. But your email reminded me of a similar story, equally ridiculous in terms of the stand-off between Madrid and the separatists. Apparently there’s a former ETA commander languishing in prison taking a degree in psychology to help pass the time. His exam results–and those of several of his former comrades–have been off the charts, prompting Aznar to suggest that they’ve either been cheating or that the examiners are too scared to give them anything less than 90%.

All the best

Alec

The second email comes through on AOL.

From: sricken1789@hotmail.com

To: almmlalam@aol.com

Subject: Coming to Madrid

Hi–

As expected, Heloise has now kicked me out of the house. The house that I paid for. Logic?

So I’m booked on the Friday easyjet. It lands at 5.15 in Madrid and I might have to stick around for a bit. Hope that’s OK. I’ve taken three weeks off work to clear my head. Could go to Cadiz as well to stay with a mate down there.

Don’t worry about picking me up, I’ll get a cab. Just tell me your address. (And don’t do the seven different email/dead drop/is this line secure?/smoke signal bullshit.) Just hit ‘Reply’ and tell me where you live. NOBODY’S WATCHING, ALEC. You’re not Kim Philby.

Anyway, really looking forward to seeing you.

Saul

So he’s finally coming. The keeper of the secrets. After six years, my oldest friend is on his way to Spain. Saul, who married a girl he barely knew just two summers ago and already lies on the brink of divorce. Saul, who holds a signed affidavit recounting in detail my relationship with MI5 and SIS, to be released to the press in the event of any ‘accident’. Saul, who was so angry with me in the aftermath of what happened that we did not speak to each other for three and a half years.

There’s a knock at the door, a soft, rapid tap. I switch off the TV, close the computer, quickly check my reflection in the mirror and cross the room.

Sofía is wearing her hair up and has a sly, knowing look on her face. Giving off an air of mischief as she glances over my shoulder.

‘Hola,’ she says, touching my cheek. The tips of her fingers are soft and cold. She must have returned home after work, taken a shower and then changed into a new set of clothes; the jeans she knows I like, a black roll-neck jumper, shoes with two-inch heels. She is holding a long winter coat in her left hand and the smell of her as she passes me is intoxicating. ‘What a room,’ she says, dropping the coat on the bed and crossing to the balcony. ‘What a view.’ She turns and heads to the bathroom, mapping out the territory, touching the bottles of shower gel and tiny parcels of soap lining the sink. I come in behind her and kiss her neck. Both of us can see our reflections in the mirror, her eyes watching mine, my hand encircling her waist.

‘You look beautiful,’ I tell her.

‘You also.’

I suppose these first heady moments are what it’s all about: skin contact, reaction. She closes her eyes and turns her body into mine, kissing me, but just as soon she is breaking off. Moving back into the room she scans the bed, the armchairs, the fake Picasso prints on the wall, and seems to frown at something in the corner.

‘Why have you brought a suitcase?’

The porter had put it near the window, half-hidden by curtains and leaning up against the wall.

‘Oh, that. It’s just full of old newspapers.’

‘Newspapers?’

‘I didn’t want the receptionist to think that we were renting the room by the hour. So I brought some luggage. To make things look more normal.’

Sofía’s face is a picture of consternation. She is married to an Englishman, yet our behaviour continues to baffle her.

‘It’s so sweet,’ she says, shaking her head, ‘so British and polite. You are always considerate, Alec. Always thinking of other people.’

‘You didn’t feel awkward yourself? You didn’t feel strange when you were crossing the lobby?’

The question clearly strikes her as absurd.

‘Of course not. I felt wonderful.’

‘Vale.’

Outside, in the corridor, a man shouts, ‘Alejandro! Ven!’ as Sofía begins to undress. Slipping out of her shoes and coming towards me on bare feet, letting the jumper fall to the floor and nothing beneath it but the cool dark paradise of her skin. She starts to unbutton my shirt.

‘So maybe you booked the room under a false name. And maybe my uncle is staying next door. And maybe somebody will see me when I go home across the lobby at 3 a.m. tonight. And maybe I don’t care.’ She unclips her hair, letting it fall free, whispering, ‘Relax, Alec. Tranquilo. Nobody in the whole world cares about us. Nobody cares about us at all.’

THREE

Taxi Driver

Saul’s plane touches down at 5.55 p.m. the following Friday. He calls from the pre-customs area using a local mobile phone: there’s no international prefix on the read-out, just a nine-digit number beginning with 625.

‘Hi, mate. It’s me.’

‘How are you?’

‘The plane was late.’

‘It’s normal.’

The line is clear, no echo, although I can hear the thrum of baggage carousels revolving in the background.

‘Our suitcases are coming out now,’ he says. ‘Shouldn’t be long. Is it easy getting a cab?’

‘Sure. Just say “Calle Princesa”, like “Ki-yay”, then “Numero dee-ethy-sais”. That means sixteen.’

‘I know what it means. I did Spanish O level.’

‘You got a D.’

‘How much does it cost to get to your flat?’

‘Shouldn’t be more than thirty euros. If it is, I’ll come down to the street and tell the driver to go fuck himself. Just act like you live here and he won’t rip you off.’

‘Great.’

‘Hey, Saul?’

‘Yes?’

‘How come you’ve got a Spanish mobile? What happened to your normal one?’

It is the extent of my paranoia that I have spent three days wondering if he has been sent here by MI5; if John Lithiby and Michael Hawkes, the controllers of my former life, have equipped him with bugs and a destructive agenda. Can I sense him hesitating over his reply?

‘Trust you to notice that. Philip fucking Marlowe. Look, a mate of mine used to live in Barcelona. He had an old Spanish SIM that he no longer used. It has sixty euros of credit on it and I bought it off him for ten. So chill your boots. I’ll be there in about an hour.’

An inauspicious start. The line goes dead and I stand in the middle of my apartment, breathing too quickly, ripped out by nerves. Relax, Alec. Tranquilo. Saul hasn’t been sent here by Five. Your friend is on the brink of getting divorced. He needed to get out of London and he needed somebody to talk to. He has been betrayed by the woman he loves. He stands to lose his house and half of everything he owns. In times of crisis we turn to our oldest friends and, in spite of everything that has happened, Saul has turned to you. That tells you something. That tells you that this is your chance to pay him back for everything that he has ever done for you.

Ten minutes later Sofía calls and whispers sweet nothings down the phone and says how much she enjoyed our night at the hotel, but I can’t concentrate on the conversation and make an excuse to cut it short. I have never had a guest in this apartment and I check Saul’s room one last time: there’s soap in the spare bathroom, a clean towel on the rail, bottled water if he needs it, magazines beside the bed. Saul likes to read comics and crime fiction, thrillers by Elmore Leonard and graphic novels from Japan, but all I have are spook biographies–Philby, Tomlinson–and a Time Out guide to Madrid. Still, he might like those, and I arrange them in a tidy pile on the floor.

A drink now. Vodka with tonic to the brim of the glass. It’s gone inside three minutes so I pour another which is mostly ice by half past seven. How do I do this? How do I greet a friend whose life I placed in danger? MI5 used Saul to get to Katharine and Fortner. The four of us went to the movies together. Saul cooked dinner for them at his flat. At an oil-industry function in Piccadilly he unwittingly facilitated our initial introduction. And all without the slightest idea of what he was doing; just a decent, ordinary guy involved in something catastrophic, an eventually botched operation that cost people their careers, their lives. How do I arrange my face to greet him, given that he is aware of that?

FOUR

The Keeper of the Secrets

At first it’s all nervous silences and small talk. There’s no big reunion speech, no hug or handshake. I fetch him from the taxi and we step into the narrow, cramped lift in my building and Saul says, ‘So this is where you live?’ and I reply, ‘Yeah,’ and then we don’t say anything for three floors. Once inside, there’s twenty minutes of ‘Nice place, man,’ and ‘Can I get you a cup of tea?’ and ‘It’s really good of you to put me up, Alec,’ and then he sits there awkwardly on the sofa like a potential buyer who has come round to view the flat. I want to rip out all the decorum and the anxiety and say how sorry I am, face to face, for the pain that I have caused him, but we must first endure the initiation rite of British politesse.

‘You’ve got a lot of DVDs.’

‘Yeah. Spanish TV sucks and I don’t have satellite.’

I am astonished by the weight he has put on, puffy fat slung round his neck and stomach. He looks worn out, barely the man I remember. At twenty-five, Saul Ricken was lean and lively, the friend everyone wanted to have. He had money in the bank, enough for him to write and to travel, and a medley of gorgeous, jealousy-inducing girlfriends. Everything seemed possible in his future. And then what happened? His adulterous French wife? His best friend? Did Alec Milius happen to him? The man facing me is a burnt-out case, an early mid-life crisis of exhaustion and excess fat. And it shames me that there is still a mean, competitive part of my nature that is glad about this; Saul is deeply troubled, and I am not the only one of us in decline.

‘Anybody else been to stay?’ he asks.

‘Not here,’ I tell him. ‘Mum came to a different place. A flat I was renting in Chamberí. About three years ago.’

‘Does she know about everything?’

This is the first moment of frankness between us, an acknowledgement of our black secret. Saul looks at the floor as he asks the question.

‘She knows nothing,’ I tell him.

‘Right.’

Maybe I should give him something else here, try to be a little more forthcoming.

‘It’s just that I didn’t have the guts, you know? I didn’t want to burst her bubble. She still thinks her son is a success story, a demographic miracle earning eighty grand a year. I’m not even sure she’d understand.’

Saul is nodding slowly. ‘No,’ he says. ‘It’s like having the drugs conversation with your parents. You think they’ll empathize when you tell them that you’ve taken E. You think they’ll be fascinated to learn that lines of charlie are regularly hoovered up in the bathrooms of every designer restaurant in London. You think that bringing up the subject of smoking hash at university is in some way going to bring you closer together. But the truth is they’ll never get it; in a fundamental way you always remain a child in your parents’ eyes. You tell your mum that you worked for MI5 and MI6 and that Kate and Will were murdered as a direct result of that, she’s not going to take it all that well.’

To hear him talk of Kate’s death like this is buckling. I had thought for some reason that Saul would let me off the hook. But that is not his style. He is direct and unambiguous and if you’re guilty of something he will call you on it. The awful shiver of guilt, the fever, washes through me as we sit facing one another across the room. Saul is looking at me with a terrible, isolating indifference; I cannot tell if he is upset or merely laying down the facts. There was certainly no suggestion of anger in the way that he broached the subject; perhaps he just wants to let me know that he has not forgotten.

‘You’re right,’ I manage to tell him. ‘Of course you’re right.’

He stands now, opens the window and steps out onto the narrow balcony which overlooks Princesa. Peering down at the street below, at the heavy traffic passing behind a line of mottled plane trees, he shouts out, ‘Noisy here,’ and frowns. What is he thinking? The characteristics of his face have been altered so much by age that I cannot even read his mood.

‘Why don’t you come inside, have a drink or something?’ I suggest. ‘Maybe you’d like a bath.’

‘Maybe.’

‘There’s not much hot water. Spaniards prefer showers. But then we could go out for dinner. I could show you round.’

‘Fine.’

Another silence. Does he want an argument? Does he want to have it out now?

‘Did you have any trouble with customs?’ I ask.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Leaving England. Did they search your bag?’

If John Lithiby had wanted to find out if Saul was bringing anything to me, he would have alerted Customs and Excise at Luton and instructed them to search his luggage.

‘Of course not. Why would they do that?’

He closes the balcony doors, muffling the sound of traffic, and begins pacing towards the kitchen. I follow him and try to seem relaxed, cloaking my paranoia in an easy, upbeat voice.

‘It’s just a possibility. If the cops want to check somebody’s stuff without raising suspicion, they hold everybody up and go through all the bags, maybe put a plain clothes officer in the queue to plant a rumour about a drugs bust or a bomb threat…’

‘What the fuck are you talking about? I went to HMV and Costa Coffee. Had an overpriced latte and nearly missed my flight.’

‘Right.’

More silence. Saul has found his way into my bedroom and is peering at the framed photographs on the wall. There’s one of Mum and Dad together in 1982, and a shot of Saul as a teenager with spiked hair. He stares at this for a long time, but doesn’t say anything about it. He probably thinks I hung it there this morning just to make him feel good.

‘I’ll tell you one thing about Luton airport,’ he says eventually. ‘Ann Summers. Don’t you love that? Just the thought process behind putting a lingerie shop in the pre-flight area. Couples going on holiday, probably haven’t had sex since 1996, then one of them spots the black suspender belt in the window. The shop was packed. Every father-of-three handing over wads of cash for a soft lace teddy and a pair of jelly handcuffs. It’s like announcing that you’re planning to have sex on the Costa del Sol. You might as well use the PA system.’

Taking advantage of his lighter mood, I fetch Saul a bottle of Mahou from the fridge and begin to think that everything is going to be OK. We make a plan to walk up to Bilbao metro to play chess at Café Comercial and he takes a shower after unpacking his bag. I notice that he has brought a laptop with him but assume that this is because of work. While waiting I wash up some mugs in the kitchen and then send a text to Sofía’s work mobile.

Have friend staying from England. Will call you after the weekend. Agree about the hotel…

A minute later she responds:

A friend? I did not think alec milius had friends…xxxx

I don’t bother replying. At 8.30 Saul emerges into the sitting room wearing a long coat and a pair of dark, slip-on Campers.

‘We’re off?’ he asks.

‘We’re off.’

FIVE

Ruy Lopez

Café Comercial is located at the southern end of Glorieta de Bilbao, a junction of several main streets–Carranza, Fuencarral, Luchana–that converge on a roundabout dominated by a floodlit fountain. If you read the guidebooks, the café has been a favoured haunt of poets, revolutionaries, students and assorted dissidents for almost a hundred years, although on an average evening in 2003 it also boasts its fair share of tourists, civil servants and mobile-clutching businessmen. Saul walks ahead of me through the heavy revolving doors and glances to his right at a crowded bar where bag-eyed madrileños are tucking into coffee and plates of microwave-heated tortilla. I indicate to him to keep walking into the main body of the café, where Comercial’s famously grumpy, white-jacketed waiters are bustling back and forth among the tables. For the first time he seems impressed by his surroundings, nodding approvingly at the high marbled columns and the smoked-glass mirrors, and it occurs to me that this is a foreign visitor’s perfect idea of cultivated European living: café society in all its glory.

The upper storey of the Comercial is used as a club on Tuesday and Friday evenings by an eclectic array of chess-loving locals. Men, ranging in ages from perhaps twenty-five to seventy, gather in an L-shaped room above the café, cluttered with tables and green leather banquettes. Very occasionally a woman will look in on the action, although in four years of coming here twice a week I have never noticed one taking part in a game. This might be sexism–God knows, still a familiar feature of twenty-first-century Spain–but I prefer to think of it simply as a question of choice: while men battle it out at chess, the nearby tables will be occupied by groups of chattering middle-aged women, happier with the calmer arts of cards or dominoes.

Coming here on such a regular basis has been a risk, but chess at Comercial is a luxury that I will not deny myself; it is three hours of old-world charm and decency, uninterrupted by regret or solitude. I know most of the men here by name, and not an evening goes by when they do not seem pleased to see me, to welcome me into their lives and friendships, the game merely an instrument in the more vital ritual of camaraderie. Still, back in 1999, I introduced myself to the secretary using a false name, so it’s necessary for me to stop Saul halfway up the stairs and explain why he cannot call me Alec.

‘Come again?’

‘All of the guys here know me as Patrick.’

‘Patrick.’

‘Just to be on the safe side.’

Saul shakes his head with bewildered, slow-motion amusement, turns, and climbs the remaining few steps. You can already hear the snap and rattle of dominoes, the rapid punch of clocks. Through the doorway opposite the landing I spot Ramón and a couple of the other, younger players who show up from time to time at the club. As if sensing me, Ramón looks up, raises his hand and smiles through a faint mist of cigarette smoke. I fetch a board, a clock and some pieces and we settle down at the back of the room, some way off from the main action. If Saul wants to talk about his marriage, or if I feel that the time is right to discuss what happened to Kate, I don’t want any of the players listening in on our conversation. One or two of them speak better English than they let on, and gossip is an industry I can ill afford.

‘You come here a lot?’ he asks, lighting yet another Camel Light.

‘Twice a week.’

‘Isn’t that a bad idea?’

‘I don’t follow.’

‘From the point of view of the spooks.’ Saul exhales and smoke explodes off the surface of the board. ‘I mean, aren’t they on the look-out for that sort of thing? Your pattern? Won’t they find you if you keep coming here?’

‘It’s a risk,’ I tell him, but the question has shaken me. How does Saul know a tradecraft term like ‘pattern’? Why didn’t he say ‘routine’ or ‘habit’?

‘But you keep a look-out for new faces?’ he says. ‘Try to keep a low profile?’

‘Something like that.’

‘And it’s the same thing in your normal life? You never trust anybody? You think death is lurking just round the corner?’

‘Well, that’s putting it a bit melodramatically, but, yes, I watch my back.’

He finishes arranging the white pieces and my hand shakes slightly as I set about black. Again the nonsensical idea arises that my friend has been turned, that the breakdown of his marriage to Heloise is just a fiction designed to win my sympathy, and that Saul has come here at the behest of Lithiby or Fortner to exercise a terrible revenge.

‘What about girlfriends?’ he asks.

‘What about them?’

‘Well, do you have one?’

‘I do OK.’

‘But how do you meet someone if you don’t trust her? What happens if a beautiful girl approaches you in a club and suggests the two of you go home together? Do you think about Katharine? Do you have to turn the woman down on the off-chance she might be working for the CIA?’

Saul’s tone here is just this side of sarcastic. I set the clock to a ten-minute game and nod at him to start.

‘There’s a basic rule,’ I reply, ‘which affects everyone I come into contact with. If a stranger walks up to me unprompted, no matter what the circumstances, I assume they’re a threat and keep them at arm’s length. But if by a normal process of introduction or flirtation or whatever I happen to get talking to somebody that I like, well then that’s OK. We might become friends.’

Saul plays pawn to e4 and hits the clock. I play e5 and we’re quickly into a Spanish Game.

‘So do you have many friends out here?’

‘More than I had in London.’

‘Who, for instance?’

Is this for Lithiby? Is this what Saul has been sent to find out?

‘Why are you asking so many questions?’

‘Jesus!’ He looks at me with sudden despair, leaning back against his seat. ‘I’m just trying to find out how you are. You’re my oldest friend. You don’t have to tell me anything if you don’t want to. You don’t have to trust me.’

There’s genuine pain, even disgust in this single word. Trust. What am I doing? How could I possibly suspect that Saul has been sent here to damage me?

‘I’m sorry,’ I tell him, ‘I’m sorry. Look, I’m just not used to conversations like this. I’m not used to people getting close. I’ve built up so many walls, you know?’

‘Sure.’ He takes my knight on c6 and offers a sympathetic smile.

‘The truth is I do have friends. A girlfriend even. She’s in her early thirties. Spanish. Very smart, very sexy.’ It wouldn’t, given the circumstances, be politic to tell Saul that Sofía is married. ‘But that’s enough for me. I’ve never needed much more.’

‘No,’ he says, as if in sorrowful agreement. With my pawn on h6, he plays bishop b2 and I castle on the king’s side. The clock sticks slightly as I push the button and both of us check that the small red timer is turning. ‘What about work?’ he asks.

‘That’s also solitary.’

For the past two years I have been employed by Endiom, a small British private bank with offices in Madrid, performing basic due diligence and trying to increase their portfolio of expat clients in Spain. The bank also offers tax-planning services and investment advice to the many Russians who have settled on the south coast. My boss, a bumptious ex-public schoolboy named Julian Church, employed me after he heard me speaking Russian to a waiter at a restaurant in Chueca. Saul knows most of this from emails and telephone conversations, but he has little knowledge of financial institutions and precious little interest in acquiring any.

‘You told me that you just drive around a lot, drumming up clients in Marbella…’

‘That’s about right. It’s mostly relationship driven.’

‘And part-time?’

‘Maybe ten days a month, but I get paid very well.’

As people grow older they tend to display an almost total indifference to their friends’ careers, and certainly Saul does not appear to be concentrating very intently on my replies. A few years back he would have wanted to know everything about the job at the bank: the car, the salary, the prospects for promotion. Now that sense of competition between us appears to have dissipated; he cares more about our game of chess. Stubbing out his cigarette he slides a pawn to c4 and nods approvingly at the move, muttering ‘here it comes, here it comes’ under his breath. The opening has been played at speed and he now looks to have a slight advantage: the centre is being squeezed up by white and there’s not much I can do except defend deep and wait for the onslaught.

‘I’ll have that,’ he says, seizing one of my pawns, and before long a network of threats has built up against my king. The clock keeps sticking and I call for time.

‘What are you doing?’ he asks, looking at my hand as though it were diseased.

‘I just need a drink,’ I tell him, balancing the timer buttons so that the mechanism stops working. ‘There’s never a waiter up here when you need one.’

‘Let’s just finish the game…’

‘…Two minutes.’

I spin round in my seat and spot Felipe serving a table of players. Behind me Saul clicks alight another cigarette and exhales his first drag with moody frustration.

‘You always do this, man,’ he mutters. ‘Always…’

‘Hang on, hang on…’

Felipe catches my eye and comes ambling over with a tray full of empty coffee cups and glasses. ‘Hola, Patrick,’ he says, slapping me on the back. Saul sniffs. I order a beer for him and a red vermouth for me and then we reset the clock.

‘Everything all right now?’

‘Everything’s fine.’

But of course it’s not. The position on the board has become hopeless, a phalanx of white rooks, bishops and pawns bearing down on my defences. I hate losing the first game; it’s the only one that really matters. For an instant I consider moving one of my pieces when Saul is not looking, but there is no way that I could get away with it without risking being caught. Besides, my days of cheating him are supposed to be over. He was always the better player. Let him win.

‘You’re resigning?’

‘Yeah,’ I tell him, laying down my king. ‘It doesn’t look good. You did well. Been playing a lot?’

‘But you could win on time,’ he says, indicating the clock. ‘That’s the whole point. It’s a speed game.’

‘Nah. You deserved it.’

Saul looks bewildered and essays a series of lopsided frowns.

‘That’s not like you,’ he says. ‘I’ve never known you to resign.’ Then, with mock seriousness, ‘Maybe you have changed, Patrick. Maybe you have become a better person.’

SIX

The Defence

Whenever I’ve thought about Saul in the last few years, the process has always begun with the same mental image: a precise memory of his face as I confessed to him the extent of my work for MI5. It was the morning of a summer’s day in Cornwall, Kate and Will not twelve hours dead, and Saul drinking coffee from a chipped blue mug. By telling him, I was placing his life in danger in order to protect my own. It was that simple: my closest friend became the guardian of everything that had happened, and the Americans could not touch me as a result. To this day I do not know what he did with the disks that I gave him, with the lists of names and contact numbers, the Caspian oil data and the sworn statement detailing my role in deceiving Katharine and Fortner. He may even have destroyed them. Perhaps he handed them immediately to Lithiby or Hawkes and then hatched a plot to destroy me. As for Kate, the grieving did not properly begin for days, and then it followed me ceaselessly, through Paris and St Petersburg, from the apartment in Milan to the first years in Madrid. The loss of first love. The guilt of my role in her death. It was the one hard fact that I could never escape. Kate and Will were the ghosts that tied me to a corrupted past.

But I remember Saul’s face at that moment. Quiet, watchful, gradually appalled. A young man of integrity, someone who knew his own mind, recognizing the limits of a friend’s morality. It was perhaps naïve to expect him to be supportive, but then spies have a habit of overestimating their persuasive skills. Instead, having tacitly offered his support, he took a long walk while I packed up the car and then left for London. It was almost four years before he contacted me again.

‘So, do you miss London?’ he asks, pulling on his coat as we swing back out through the revolving doors, heading south down Calle Fuencarral. It’s approaching ten o’clock and time to find somewhere to eat.

‘All the time,’ I reply, which is an approximation of the truth. I have come to love Madrid, to think of the city as my home, but the tug of England is nagging and constant.

‘What do you miss about it?’

I feel like Guy Burgess being interviewed in Another Country. What does he tell the journalist? I miss the cricket.

‘Everything. The weather. Mum. Having a pint with you. I miss not being allowed to be there. I miss feeling safe. It feels as though I’m living my life with the handbrake on.’

Saul scuffs his shoes on the pavement, as if to kick this sentiment away. Two men are walking hand-in-hand in front of us and we skirt round them. It is becoming difficult to move. I know a good seafood restaurant within three blocks–the Ribeira do Miño–a cheap and atmospheric Galician marisquería where the owner will slap me on the back and make me look good in front of Saul. I suggest we eat there and get away from the crowds and within a few minutes we have turned down Calle de Santa Brígida and settled at a table at the back of the restaurant. I take a seat facing out into the room, as I always do, in order to keep an eye on who comes in and out.

‘They know you here?’ he asks, lighting a cigarette. The manager wasn’t around when we came in, but one of the waiters recognized me and produced an acrobatic nod.

‘A little bit,’ I tell him.

‘Gets busy.’

‘It’s the weekend.’

Resting his cigarette in an ashtray, Saul unfolds the napkin on his plate and tears off a slice of bread from a basket on the table. Crumbs fall on the cloth as he dips it into a small metal bowl filled with factory mayonnaise. Every table in the place is filled to capacity and an elderly couple are sitting directly beside us, tackling a platter of crab. The husband, who has a lined face and precisely combed hair, occasionally cracks into a chunky claw and sucks noisily on the flesh and the shells. There’s a smell of garlic and fish and I think Saul likes it here. Using his menu Spanish he orders a bottle of house wine and shapes himself for a serious conversation.

‘Out on the street, when you said you missed not being allowed to go home, what did you mean by that?’

‘Just what I said. That it’s not possible for me to go back to England. It’s not safe.’

‘According to who?’

‘According to the British government.’

‘You mean you’ve been threatened with arrest?’

‘Not in so many words.’

‘But they’ve taken your passport away?’

‘I have several passports.’

The majority of madrileños do not speak English, so I am not too concerned about the couple sitting beside us who appear to be lost in an animated conversation about their grandchildren. But I am naturally averse to discussing my predicament, particularly in such a public place. Saul rips off another chunk of bread and inhales on his cigarette. ‘So what exactly’s the problem?’

He may be looking for a fight.

‘The problem?’

The waiter comes back. Slapping down a bottle of unlabelled white wine, he asks if we’re ready to order and then spins away when I ask for more time. It is suddenly hot at our table and I take off my sweater, watching Saul as he pours out two glasses.

‘The problem is straightforward.’ It is suddenly difficult to articulate, to defend, one of my deepest convictions. ‘I worked for the British government in a highly secret operation designed to embarrass and undermine the Yanks. I was caught and I was fired. I threatened to spill the beans to the press and told two of my closest friends about it. In the corridors of Thames House and Vauxhall Cross, I’m not exactly Man of the Year.’

‘You think they still care?’

The question is like a slap in the face. I pretend to ignore it but Saul looks pleased with himself, as if he knows he has landed a blow. Why the hostility? Why the cynicism? Short of something to say, I pick up the menu and decide, more or less at random, what both of us are going to eat. I don’t consult Saul about this and gesture at the waiter with a wave of my hand. He comes over immediately and flicks open a pad.

‘Sí. Queremos pedir pimientos de padrón, una ración de jamón ibérico, ensalada mixta para dos y el plato de gambas y cangrejos. Vale?’

‘Vale.’

‘And don’t forget the chips,’ Saul says, the sarcasm drifting away.

‘Look.’ Suddenly the absurdity of my situation in a stranger’s eyes has become worryingly clear. I need to get this right. ‘We’re America’s only friend in the world, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health. They do what they like, we do what they tell us. It’s a one-way friendship which nevertheless needs to look rock solid or Europe will be singing the “Marseillaise”. So having somebody like me at large is potentially a huge embarrassment.’

Saul actually smirks. ‘You don’t think you’re slightly overestimating your importance?’

It’s pure goading, poking around for a reaction. Don’t rise to it. Don’t bite.

‘Meaning?’

‘Meaning things have moved on since 1997, mate. Men have flown large planes into very tall buildings. The CIA is looking for anthrax in downtown Baghdad. They’re not worrying about whether Alec Milius is getting cleared through customs at Gatwick airport. We’re days away from invading Iraq, for Christ’s sake. You think your average MI5 officer is concerned about a tiny operation that went wrong five years ago? You don’t think he’s got other things on his mind?’

I drain my glass and refill it without saying a word. Saul breathes a funnel of smoke at a fishing net tacked erratically to the wall and I am on the point of losing my temper.

‘So you think I’m delusional? You think the fact that five years ago my apartment in Milan was ransacked by the CIA is just a product of a fertile imagination?’

‘When were you living in Milan?’

‘For six months in ‘98.’

Saul looks stunned. ‘Jesus.’

‘I couldn’t tell you. I couldn’t tell anyone.’

He recovers almost immediately. ‘But that could have been just a burglary. How do you know it was the Yanks?’

I actually enjoy what comes next, wiping the smug look off his face. ‘I know because Katharine told me about it on the phone. She said that Fortner, the man who taught her everything, her mentor and father figure, had lost his job as a result of what I’d done and that he still hadn’t found work two years later. A veteran CIA officer hoodwinked by a 25-year-old rookie selling fake research data for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Both of them were made to look a laughing stock by what I did to them. She said that her own career was as good as over. Back to desk work in Washington, blown for all European operations. And all because of Alec Milius. Katharine spent two years after I disappeared trying to discover where I’d gone. I think she went a bit crazy. Eventually she tracked me to my apartment in Milan, got my phone number, address, everything. I’d been sloppy. The CIA broke in, took my computer, passport, even my fucking car that was parked outside. I had nine thousand dollars cash under a mattress. That went as well. Katharine said it was just payback for what I stole from her “organization”. Hence the need to get the hell out of Italy. Hence the reason why I’ve been just a little bit paranoid ever since I got to Madrid.’

‘They don’t know you’re here?’

‘Somebody knows I’m here.’

‘What do you mean, “Somebody knows I’m here”?’

I am aware that what I’m about to tell Saul may sound over-the-top, but it’s important to me that he should understand the seriousness of my predicament.

‘My letters have been tampered with, my car has been followed, one of my mobile phones was tapped–’

Saul interrupts. ‘When did this happen?’

‘It happens all the time. You haven’t seen me since I moved here. You don’t know what Spain is like. Just realize that they keep an eye on me, OK, that’s all I’m saying.’

‘Even now? Nearly six years on?’

‘Five years, two hundred and thirty-eight days. Look. I have five bank accounts. When I call one of them and they put me on hold, I think it’s because there’s a note against my name and they’re checking me out. I have to change my phone every three weeks. If someone is listening to a Walkman next to me on the metro, I make sure they’re not wearing a wire. The other day I was driving to Granada and the same car followed me from Jaén for an hour.’

‘So? Maybe they were connected to Endiom. Maybe they were lost. You know how someone very high on coke will ask you the same question over and over again?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well that’s what you sound like. Somebody very high. Somebody very paranoid. Your emails, talking to you on the phone, listening to you now. OK, five years ago, as a one-off, Katharine tracked you down and gave you a scare. She was pissed off, she had a right to be. But she’s a big girl, she would have got over it by now. The rest of this is not happening, Alec. You’re living in cloud cuckoo land. For once in your life, try to see beyond your own ego. Christ, you wouldn’t even come to my wedding. Believe me, if the CIA or Five or Six had really wanted to make your life difficult, they would have done it by now. Somebody could have planted drugs on you, got you thrown in jail. Not just turned over your flat. You get people on the run like Tomlinson or Shayler and they make it impossible for them to move. No work, no residency, threats and broken promises. You’re a fucking footnote, Alec.’

Food suddenly arrives in waves: a flat pink plate of jamón wedged in near my elbow; a deep metal bowl of salad tossed with carrot and canned tuna; the house speciality of prawns piled eight inches high on a rock of boiled crab and razor fish; a platter of pimientos de padrón, charred and salted to perfection.

Saul asks quietly what we’re eating.

‘They’re grilled peppers. One in ten is supposed to be hot. As in spicy. You’ll like them.’ He bites at one and nods approvingly. ‘Look, there’s one thing you should understand.’

‘And what’s that?’

‘I am not delusional. I am not paranoid.’ I’m not a fucking footnote, either.

‘Fine,’ he says.

‘I’m just trying to live my life…’

‘…with the handbrake on.’

Silence. It is as if the whole notion of my exile is a joke to him.

‘Why are you being like this? Why are you trying to goad me?’

Saul has been piling salad onto his plate but he stops and fixes my gaze.

‘Why? Because I no longer have any idea who you are, what you stand for. A person changes, of course they do, it’s a natural process. They find work, they find something that fulfils them, they meet the right girl, blah blah blah. At least that’s the idea. And as you get older you’re supposed to work out what’s important to you and dump what isn’t. It’s naive to think that at thirty a person is going to be the same animal that they were at twenty. Life has an impact.’

I mutter, ‘Of course it does,’ as if to dilute what’s coming, but Saul is shaking his head.

‘Something fundamental shifted in you five years ago, man. You were my closest, my oldest friend. We went to school together, to university. But I had literally no idea that you were capable of doing what you did. One day you were just reticent, ironic, mildly ambitious Alec Milius; the next you’re this creature of the state, a lying, manipulating, barely moral…thing, risking everything in your life for what exactly? To this day I can’t get my head round it. Personal fulfilment? Patriotism? And you used me in that, you used our friendship. Three straight years of lies. Every day it affected me, like the loss of someone, like mourning.’

All of the shame and despair and regret that I have experienced since Kate’s death is crystallized in this instant. Saul’s face is as hard and as unforgiving as I can ever remember seeing it. It is the end of our friendship. With just a few stark sentences he has engendered a violent and sudden cut-off.

‘So that’s it?’

‘That’s what?’

‘The end of things between us? That’s what you came out here to tell me? That it’s better if I don’t contact you any more?’

‘What the fuck are you talking about?’

‘You said it yourself. I’m a liar, a manipulator. I’m a footnote.’

‘That doesn’t mean it’s the end of our friendship.’ Saul looks at me in amazement, as if I have completely misjudged both him and the situation. ‘Jesus, we’re not at school any more, Alec. This isn’t a playground.’ I stare down at the table and cradle the back of my neck, bewildered and embarrassed. ‘Short of you developing an all-new fixation with Catalan schoolboys we’re still going to be mates. Things don’t end between people just because they betray them. In fact, that’s probably when they start to get interesting.’ There is a long burst of applause from the next-door room. ‘Let’s face it, we’re always more grateful to the people who have hurt us in life than to the ones who just let things drift by. I learned from you, and that’s what it’s all about. I’m just not going to sit here and let you think that no harm came from what happened…’

‘Believe me, I don’t think that for a second.’

‘Let me finish. It’s important for me to say this to you, face to face. I don’t get the chance on email. I don’t get the chance on the phone.’

‘OK.’

‘What you did was wrong. You didn’t kill Kate or Will, but your work and your lying led to their deaths. And I don’t see you doing anything out here to put that right. I don’t see you making amends.’

Ordinarily I might challenge Saul on this. Make amends? Who is he to speak to me this way? I make amends with my solitude. I pay penance with exile. But he has always believed in the myth of self-improvement; any reasoning I might employ would only burn out in the fire of his moral authority. We find ourselves eating in silence, as if there is nothing left to be said. I could try to defend myself but it would only feel like a tactic, a lie, and Saul would jump on it as quickly as he leaped on my earlier defence. At the next table the grandparents are standing up with considerable effort, having paid their bill and left just a few small coins as a tip. At the base of their receipt it says ‘No A La Guerra’ and the waiter has written ‘Gracias’ in felt-tip pen. The husband helps his wife into a garish fur coat and casts both of us an inscrutable smile. Perhaps he understood English after all. For once, I do not care.

‘Jesus!’

Saul has bitten into a hot padrón and downs an entire glass of wine to kill the heat.

‘You OK?’

‘Fine,’ he says, pursing his cheeks. ‘We need more booze.’

And this small incident seems to break the spell of his disquiet. A second bottle comes and we spend the rest of the meal talking about Chelsea and Saddam Hussein, about Saul’s grandfather–who has lung cancer–and even Heloise, whom he is inclined to forgive in spite of her blatant adultery. I note the double-standard in his attitude to the two of us and wonder if there is something saintly in Saul which actually encourages people to betray him. There has certainly always been an element of masochism in his personality.

With coffee, the waiter brings us two small shots of lemon liqueur–on the house–and we down them in a gulp. Saul is keen to pay (‘as a present, for putting me up’) and I feel mildly drunk as we make our way out past the kitchen and into the bustle of Chueca. It is past midnight and the nightlife is well under way.

‘You know a decent bar?’ he asks.

I know plenty.

SEVEN

Churches

Spaniards dedicate so much of their lives to enjoying themselves that a word actually exists to describe the span of time between midnight and 6 a.m., when ordinary European mortals are safely tucked up in bed. La madrugada. The hours before dawn.

‘It’s a good word,’ Saul says, though he thinks he’ll be too drunk to remember it.

We leave Chueca and walk west into Malasaña, one of the older barrios in Madrid, still a haunt of drug dealers and penniless students though, by reputation, neither as violent nor as rundown as it was twenty years ago. The narrow streets are teeming and dense with crowds that gradually thin out as we head south in the direction of Gran Vía.

‘Haven’t we just been here?’ Saul asks.

‘Same neighbourhood. Further south,’ I explain. ‘We’re going in a circle, looping back towards the flat.’

A steep hill leads down to Pez Gordo, a bar I love in the neighbourhood, favoured by a relaxed, unostentatious crowd. There’s standing room only and the windows are fogged up with posters and condensation, but inside the atmosphere is typically rousing and flamenco music rolls and strums on the air. I get two cañas within a minute of reaching the bar and walk back to Saul, who has found us a spot a few feet from the door.

‘Do you want to hear my other theory?’ he says, jostled by a customer with dreadlocked hair.

‘What’s that?’

‘I know the real reason you like living out here.’

‘You do?’

‘You thought that moving overseas would give you a chance to wipe the slate clean, but all you’ve done is transfer your problems to a different time zone. They’ve followed you.’

Here we go again.

‘Can’t we talk about something else? It’s getting a little tedious, all this constant self-analysis.’

‘Just hear me out. I think that some days you wake up and you want to believe that you’ve changed, that you’re not the person you were six years ago. And other times you miss the excitement of spying so much that it’s all you can do not to ring SIS direct and all but beg them to take you back. That’s your conflict. Is Alec Milius a good guy or a bad guy? All this paranoia you talk about is just window-dressing. You love the fact that you can’t go home. You love the fact that you’re living in exile. It makes you feel significant.’

It amazes me that he should know me so well, but I disguise my surprise with impatience.

‘Let’s just change the subject.’

‘No. Not yet. It makes perfect sense.’ He’s toying with me again. A girl with a French accent asks Saul for a light, and I see that his nails are bitten to the quick as she takes it. He’s grinning. ‘People have always been intrigued by you, right? And you’re playing on that in this new environment. You’re a mysterious person, no roots, no past. You’re a topic of conversation.’

‘And you’re pissed.’

‘It’s the classic expat trap. Can’t cope with life back home, make a splash overseas. El inglés misterioso. Alec Milius and his amazing mountain of money.’

Why is Saul thinking about the money?

‘What did you say?’

A momentary hesitation, then, ‘Forget it.’

‘No. I won’t forget it. Just keep your voice down and explain what you meant.’

Saul grins lopsidedly and takes off his coat. ‘All I’m saying is that you came here to get away from your troubles and now they’ve passed you by. It’s time for you to move on. Time for you to do something.’

For a wild moment, undoubtedly reinforced by alcohol, it crosses my mind that Saul has been sent here to recruit me, to lure me back into Five. Like Elliott sent to Philby in Lebanon, the best friend dispatched at the state’s request. His angle certainly sounds like a pitch, although the notion is ridiculous. More likely Saul is simply adhering to that part of his nature that has always annoyed me and which I had somehow allowed myself to forget; namely, the moralizing do-gooder, the self-righteous evangelist busily saving others whilst incapable of saving himself.

‘So what do you suggest I do?’

‘Just come home. Just put an end to this phase of your life.’

The idea is certainly appealing. Saul is right that there are times when I look back on what happened in London with nostalgia, when I regret that it all came to an end. But for Kate’s death and the exhaustions of secrecy, I would probably do it all again. For the thrill of it, for the sense of being pivotal. But I can’t state that directly without appearing insensitive.

‘No. I like it here. The lifestyle. The climate.’

‘Seriously?’

‘Seriously.’

‘Well then, at least don’t change your mobile phone every three weeks. And just get one email address. Please. It pisses me off and annoys your mum. She says she still doesn’t know why you’re out here, why you don’t just come home.’

‘You’ve talked to Mum?’

‘Now and again.’

‘What about Lithiby?’

‘Who’s Lithiby?’

If Saul is working for them, they have certainly taught him how to lie. He runs his finger along the wall and inspects it for dust.

‘My case officer at Five,’ I explain. ‘The guy behind everything.’

‘Oh, him. No, of course not.’

‘He’s never been to see you?’

‘Never.’

Someone turns the music up beyond a level at which we can comfortably speak, and I have to shout at Saul to be heard.

‘So where did you put the disks?’

He smiles. ‘In a safe place.’

‘Where?’

Another grin. ‘Somewhere safe. Look, nobody’s ever been to see me. Nobody’s ever been to see your mum. It’s not as if…Alec?’

Julian Church has walked into the bar. Six inches taller than anyone else in the room and dressed like a Royal Fusilier on weekend leave. There are certain things that cannot be controlled, and this is one of them. He spots me immediately and does a little electric shock of surprise.

‘Alec!’

‘Hello, Julian.’

‘Fancy seeing you here.’

‘Indeed.’

‘Night on the tiles?’

‘Apparently. And you?’

‘The very same. My beloved wife fancied a drink, and who was I to argue?’

Julian, as ever, is delighted to see me, but I can feel Saul physically withdrawing, the cool of Shoreditch and Notting Hill reacting with violent distaste to Julian’s tasselled loafers and bottle-green cords. I should introduce them.

‘Saul, this is Julian Church, my boss at Endiom. Julian, this is Saul Ricken, a friend of mine from England.’

‘Ah, the old country,’ Julian says.

‘The old country,’ Saul repeats.

Think. How to deal with this? How do I get us away? A chill wind comes barrelling in through the open door, drawing irritated looks from nearby tables. Julian hops to it like a bellboy, muttering ‘Perdón, perdón,’ as he shuts out the cold. ‘That’s a bit better. Bloody chilly in here. Bloody noisy, too. Señora Church won’t be far behind me. She’s parking the car.’

‘Your wife?’ Saul asks.

‘My wife.’ Julian’s pale skin is flushed and pink, his widow’s peak down to a few fine strands. ‘Madness to drive into town on a Friday night, but she insisted, like most of her countrymen, and who was I to argue? You staying the weekend?’

‘A bit longer,’ Saul replies.

‘I see, I see.’

This is clearly going to happen and there’s nothing I can do about it. The four of us locked into two or three rounds of drinks, then awkward questions later. I try to keep my eyes away from the door as Julian takes off his coat and hangs it on top of Saul’s. Do I have an exit strategy? We could lie about meeting friends at a club, but I don’t want to arouse Julian’s suspicion or risk a contradiction from Saul. Best just to ride it out.

‘Did you get my email?’ Julian asks, and I am on the point of responding when Sofía walks in behind him. She does well to disguise her reaction; just a flat smile, a clever look of feigned recognition, then fixing her gaze on Julian.

‘Darling, you remember Alec Milius, don’t you?’

‘Of course.’ It doesn’t look like she does. ‘You work with my husband, yes?’

‘And this is his friend, Saul…Ricken, was it? They were here quite by chance. A coincidence.’

‘Ah, una casualidad.’ Sofía looks beautiful tonight, her perfume a lovely sense memory of our long night together at the hotel. She uncurls a black scarf, takes off her coat, kisses me lightly on the cheek and gently squeezes Julian at the elbow.

‘We’ve met before,’ I tell her.

‘Sí. At the office, yes?’

‘I think so.’

Once, when Julian was away on business, Sofía came down to the Endiom building in Retiro and we fucked on his desk.

‘I thought you two met at the Christmas party.’

‘I forget,’ Sofía replies.

She places her scarf on the surface of the cigarette machine and affords me the briefest of glances. Saul appears to be humming along to the music. He may even be bored.

‘So what’s everybody drinking?’

Julian has taken a confident stride forward to coincide with his question, breaking up the huddle around us by dint of his sheer size. Saul and I want cañas, Sofía a Diet Coke.

‘I’m driving,’ she explains, directing her attention at Saul. ‘Hablas español?’

‘Sí, un poco,’ he says, suddenly looking pleased with himself. That was clever of her. She wants to know how much she can get away with saying.

‘Y te gusta Madrid?’

‘Sí. Mucbo. Mucho.’ He gives up. ‘I just arrived tonight.’

And what follows is a pitch-perfect, five-minute exchange about nothing at all: Sofía conducting a conversation about the Prado, about tourists at the Thyssen museum, the week she spent recently in Gloucestershire with Julian’s ageing parents. Just enough chat to cover the span of time before her husband returns from the bar. When he does, all of his attention is focused on me.

‘Actually, Alec, it’s a good job we’ve bumped into each other.’ He clutches me round the shoulder. ‘Saul, can I leave you with my wife for five minutes? Need to talk shop.’

Dispensing the drinks, he steers me into a cramped space beside the cigarette machine and assumes a graver tone. The need for secrecy is unclear, although I should still be able to eavesdrop on Saul’s conversation. I don’t want him leaking information to Sofía about my past. Things are nicely compartmentalized there. They are under control.

‘Look, as I said, I need you to go to San Sebastián early next week. Is that going to be a problem?’

‘Shouldn’t be.’

‘We can pay your expenses, normal form. It’s no different to your usual work. Just diligence. Just need you to look into something.’

‘Your email said it was about cars.’

‘Yes. Client wants to build a factory making parts near the border with Navarra. Don’t ask. Blindingly dull small town. But the workforce will be mostly Basque, so there might be union trouble. I need you to put together a document, interviews with local councillors, real-estate bigwigs, lawyers and so forth. Something to impress potential investors, calm any nerves. Sections about the tax position, the impact on exports of the strengthening euro, that sort of thing. Most importantly, what effect would Basque independence have on the project?’

‘Basque independence? They think that’s likely?’

‘Well, that’s what we need you to find out.’

I’m tempted to tell Julian that Endiom would be better off buying a crystal ball and a subscription to The Economist, but if he wants to pay me

300 a day to stay in San Sebastian as a glorified journalist, I’m not going to argue. Saul has already mentioned that he wants to go to Cádiz to see a friend, so I’ll kick him out on Tuesday and take the car.

‘You want to fly there?’

‘I’ll drive.’

‘Up to you. There’s a file at the office. Why don’t you pick it up on Monday and we can go through all the bumph? Might have a spot of lunch.’

‘Done.’

But Julian won’t let me go. Rather than return to Sofía and Saul, he lingers in the corner, engaging me in a mind-numbing conversation about Manchester United’s chances in this year’s Champions League.

‘If we can just see our way past Juventus in the second group phase, there’s every chance we’ll draw Madrid in the quarter-finals.’

This goes on for ten minutes. Perhaps he is enjoying the male camaraderie, a chance to talk to somebody other than Sofía. Julian has always held me in the highest esteem, valuing my opinion on anything from Iraq to Nasser Hussain, and is strangely deferential in approach.

Behind me, Saul is sounding enamoured of Sofía, laughing at her jokes and doing his best to talk me down.

‘Yeah, we were just saying how friends change in their twenties. It’s tough staying loyal to some of them.’ This is all very pointedly within my earshot. ‘I think people used to think I was a bit of an idiot for hanging out with Alec, you know, but I felt sorry for him. There was a time when he really tested me, when I felt like cutting the rope, only I didn’t want to be the sort of person who bailed out on his mates when they were in trouble, know what I mean?’

I can’t hear Sofía’s response. Her voice is naturally quieter than Saul’s and she is speaking out into the room, with Julian in full flow leaning into me for greater emphasis.

‘I mean, most people would now agree that Roy Keane is not the player he was. Injuries have taken their toll–hip surgery, knee ligaments–he simply can’t get up and down like he used to. I wouldn’t be surprised if he goes to Celtic next season.’

‘Really? You think so?’ It’s a struggle to remember the name of Manchester United’s manager. ‘Alex Ferguson would be prepared to sell him?’

‘Well, that’s the million-dollar question. With Becks almost certainly off, would he want to lose Keano as well?’

Saul has started talking again and I try to pivot my body against the cigarette machine so that I can still hear his conversation. He’s saying that he’s known me since childhood, that he has no idea what I’m doing out here in Spain.

‘…one day he just upped and left and none of us have seen him since.’

Sofía sounds understandably inquisitive, although it’s still impossible to hear what she’s saying. Now Julian is asking me if I want a couple of spare tickets to the Bernabéu. Was that a question about London? Saul’s answer contains the phrase ‘oil business’ and now I really start to worry. Somehow I have to break away from Julian and intrude to stop their conversation.

‘Do you have a cigarette?’

I have turned and stepped up to them, my weight shifted awkwardly onto one leg, looking unguardedly at Saul as an instruction to make him shut up. He pauses mid-sentence, extracts a Camel Light and passes it to me saying, ‘Sure.’ Sofía looks startled–she has never seen me smoking–but Julian is too busy offering me a light to notice.

‘I thought you gave up?’ he asks.

‘I did. I just like having one every now and again. Late nights and weekends. What were you two talking about? My ears were burning.’

‘Your past,’ Sofía says, fanning smoke away from her face. ‘Saul says you’re a man of mystery, Alex. Did you know that, darling?’

Julian, checking messages on his mobile phone, says, ‘Sí, yup,’ and heads outside in search of better reception.

‘He also said you worked in the oil business?’

‘Briefly. Very briefly. Then I got a job at Reuters and they shipped me out to Russia. What do you do, Sofía?’

She grins and looks up at the ceiling.

‘I’m a clothes designer, Alex. For women. Didn’t you ask me that at the Christmas party?’

The tone of the question is unambiguously flirtatious. She needs to cool it or Saul will cotton on. In an attempt to change the subject, I say that I once saw Pedro Almodóvar drinking in the bar, sitting at a table not too far from where we are standing. It’s a lie–a friend saw him–but enough to interest Saul.

‘Really? That’s like going to London and seeing the Queen.’

‘Qué?’ Sofía says, her English momentarily confused. ‘You saw the Queen here?’

And, thankfully, the misunderstanding engenders the conversation I had hoped for: Saul’s lifelong distaste for Almodóvar’s movies perfectly at odds with Sofía’s loyal, madrileñian obsession.