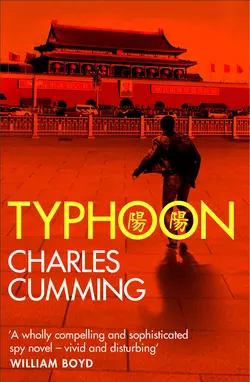

Typhoon

Charles Cumming

Perfect for fans of John le Carré, a gripping and suspenseful spy thriller from ‘the master of the modern spy thriller’ (Mail on Sunday)Hong Kong, 1997. Only a few short months of British rule remain before the territory returns to Chinese control.It’s a feverish city. And the spooks are hard at work, jostling for position and influence. So when an elderly man emerges from the sea, claiming to know secrets he will share only with the British Governor, a young MI6 officer, Joe Lennox, sees the chance to make his reputation.But when the old man, a high-profile Chinese professor, is spirited away in the middle of the night by the CIA, it’s clear that there’s a great deal more at stake here than a young spy’s career.The professor holds the key to a sinister and ambitious plan that could have catastrophic repercussions for the world in the twenty-first century…

CHARLES CUMMING

Typhoon

Copyright (#ulink_c8f305af-0755-55f7-b5d4-d69d789e0324)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by Michael Joseph, Penguin Books, in 2008

Copyright © Charles Cumming 2008

Cover photographs © Nik Keevil/Arcangel Images (man); Shutterstock.com (background)

Charles Cumming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007487189

Ebook Edition © 2013 ISBN: 9780007487219

Version: 2015-07-07

For Iris and Stanley

and

to the memory of Pierce Loughran

(1969-2005)

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u201d082d-df03-51c3-8d75-c1696146ddda)

Copyright (#u20b7998d-2589-5bd5-9cf5-5c7aabd5a266)

Dedication (#u81eb77eb-966e-5eff-9788-e10327967ec1)

Epigraph (#u2dd72c32-ca16-5cfe-a9fc-df6dee6846eb)

Map (#uf42b7c4a-6f26-5141-8ab2-113a491b28ec)

Prologue (#uacc027a7-6591-5dd5-8f2a-be2f401d1131)

Part One: Hong Kong 1997 (#u59d2ea75-2b5a-5dca-a9ea-104ef50b4606)

1. On the Beach (#uf485a995-f54e-5401-ad0b-0ab668c6be3c)

2. Black Watch (#u2225a6f4-cb8d-545a-8c49-f722157deeeb)

3. Lennox (#u45b80d7e-8b93-5fc3-b256-bd169c90d506)

4. Isabella (#uab3fb619-b563-5620-9dc6-1a129b5d4c24)

5. The House of a Thousand Arseholes (#u14e651f2-1c9e-522b-a139-46f6f29e532b)

6. Cousin Miles (#u2736d952-ae18-5720-bbf4-8f92c5830ac0)

7. Wang (#u9425ae5d-f35c-577e-9487-96c725b559e0)

8. Xinjiang (#u61741dd2-da1d-5c55-8d2f-a6f97a147129)

9. Club 64 (#uaf33dca4-bbf0-5890-8733-8de9c2888754)

10. Ablimit Celil (#u74e2e8da-6b53-5c32-9931-70d7d91b4844)

11. Tiananmen (#ua9b983ab-6b1f-521f-9fd2-8bd9bb578f36)

12. A Good Walk Spoiled (#u96f3063c-2290-569d-b1f1-718ae199c5fa)

13. The Double (#ua826f112-2d1f-50c5-bfde-ca3c824f96f8)

14. Samba’s (#u775bd32f-b40f-5020-84fd-bb2a2ee4b945)

15. Underground (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Twilight (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Quid Pro Quo (#litres_trial_promo)

18. Maryland (#litres_trial_promo)

19. The Engagement (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Chinese Whispers (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Chen (#litres_trial_promo)

22. Dinner for Two (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Wui Gwai (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Handover (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: London 2004 (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Not Quite the Diplomat (#litres_trial_promo)

26. Chinatown (#litres_trial_promo)

27. Water Under the Bridge (#litres_trial_promo)

28. Retread (#litres_trial_promo)

29. The Backstop (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Shanghai 2005 (#litres_trial_promo)

30. The Paris of Asia (#litres_trial_promo)

31. Tourism (#litres_trial_promo)

32. Sleeper (#litres_trial_promo)

33. Starbucks (#litres_trial_promo)

34. Nightcrawling (#litres_trial_promo)

35. The Morning After (#litres_trial_promo)

36. The Diplomatic Bag (#litres_trial_promo)

37. An Old Friend (#litres_trial_promo)

38. M on the Bund (#litres_trial_promo)

39. Persuasion (#litres_trial_promo)

40. Beijing (#litres_trial_promo)

41. Hutong (#litres_trial_promo)

42. Paradise City (#litres_trial_promo)

43. The French Concession (#litres_trial_promo)

44. Screen Four (#litres_trial_promo)

45. Borne Back (#litres_trial_promo)

46. The Last Supper (#litres_trial_promo)

47. Product (#litres_trial_promo)

48. Closing In (#litres_trial_promo)

49. Chatter (#litres_trial_promo)

50. 6/11 (#litres_trial_promo)

51. Beijing Red (#litres_trial_promo)

52. Bob (#litres_trial_promo)

53. The Testimony of Joe Lennox (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Charles Cumming (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The superior man understands what is right;

the inferior man understands what will sell.

Confucius

Prologue (#ulink_dd89ac50-af9d-5089-8c25-679f127aa67f)

‘Washington has gone crazy.’

I am standing at the foot of Joe’s bed in the Worldlink Hospital. Six days have passed since the attacks of 11 June. There are plastic tubes running from valves on his wrists, a cardiac monitor attached by pads to the spaces between the bruises and cuts on his chest.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Only a handful of people at Langley knew what Miles was up to. Nobody else had the faintest idea what the hell was going on out here.’

‘Who told you this?’

‘Waterfield.’

Joe turns his head towards the window and looks out on another featureless Shanghai morning. He has a broken collarbone, a fracture in his left leg, a wound on his skull protected by loops of clean white bandage.

‘How much do you know about all this?’ he asks, directing his eyes into mine, and the question travels all the way back to our first months in Hong Kong.

‘Everything I’ve researched. Everything you’ve ever told me.’

My name is William Lasker. I am a journalist. For fourteen years I served as a support agent of the British Secret Intelligence Service. For ten of those years, Joe Lennox was my handler and close friend. Nobody knows more about RUN than I do. Nobody except Joe Lennox himself.

He clears a block in his throat. His voice is still slow and uneven from the blast. I offer him a glass of water which he waves away.

‘If the CIA didn’t know about Miles, they’ll be going through every file, every email, every telephone conversation he ever made. They’ll want answers. Heads are going to roll. David Waterfield can get you those files. He has a source at Langley and a source in Beijing.’

‘What are you getting at?’

A nurse comes into the room, nods at Joe, checks the flow rate on his IV drip. Both of us stop talking. For the past six days the Worldlink has been crawling with Chinese spies. The Ministry of State Security will be keeping a record of everybody who comes in and out of this room. The nurse looks at me, seems to photograph my face with a blink of her eyes, then leaves.

‘What are you getting at?’ I ask again.

‘They say that every journalist wants to write a book.’ Joe is smiling for the first time in days. I can’t tell whether this remark is a statement or a question. Then his mood becomes altogether more serious. ‘This story needs to be told. We want you to tell it.’

PART ONE (#ulink_8b59cdc3-505b-57ea-a17f-a91f1cb522cf)

1 (#ulink_873bd659-b808-5133-9f02-501eedc375ff)

On the Beach (#ulink_873bd659-b808-5133-9f02-501eedc375ff)

Professor Wang Kaixuan emerged from the still waters of the South China Sea shortly before dawn on Thursday 10 April 1997. Exhausted by the long crossing, he lay for some time in the shallows, his ears tuned to the silence, his eyes scanning the beach. It was 5.52 a.m. By his calculations the sun would begin to rise over Dapeng Bay in less than fifteen minutes. From that point on he would run the greater risk of being spotted by a passing patrol. Keeping his body low against the slick black rocks, he began to crawl towards the sanctuary of trees and shrubs on the far side of the beach.

He was wearing only a pair of shorts and a thin cotton T-shirt. All of his worldly possessions were otherwise contained in a small black rucksack attached to the makeshift raft which he dragged behind him on a length of twine attached to his leg. The plastic containers that had floated the raft clattered and bounced on the rocks as Wang inched inshore. The noise of this was too much; he should have prepared for it. Twenty metres short of the trees he stopped and turned. Sand had begun to stick to his damp, salt-stiffened fingers and he was aware that his breathing was hard and strained. Two hours earlier, in the half-light of eastern Shenzhen, Wang had attached a cheap kitchen knife to his calf using a stretch of waterproof tape. It took all of his strength now to tear the knife free and to sever the twine so that the raft was no longer attached to his body.

Kuai dian, he told himself. Hurry. Wang cut the rucksack free and tried to sling it across his shoulders. It felt as though he had been drugged or beaten and a grim sense memory of the prison in Urumqi crept up on him like the rising sun. The rucksack was so heavy and his arms so tired from the swim that he felt he would have to rest.

Jia you.

Keep going.

He stumbled to his feet and tried to rush the last few metres to the trees, but the rucksack tipped on his back and Wang fell almost immediately, fearing an injury to his knee or ankle, something that would hamper him on the long walk south across the hills. Imagine that, after everything I have been through: a tendon sends me back to China. But he found that he could move without discomfort to the nearest of the trees, where he sank to the ground, sending a flock of startled birds clattering into the sky.

It was six o’clock. Wang looked back across the narrow stretch of water and felt a tremor of elation which numbed, for an instant, his near-constant dread of capture. He reached out and felt for the bark of the tree, for the sand at his feet. This place is freedom, he told himself. This shore is England. Starling Inlet was less than two kilometres wide, but in the darkness the tide must have pulled him west towards Sha Tau Kok, or even east into the open waters of Dapeng. Why else had it taken him so long to swim across? The professor was fit for a man of his age and he had swum well; at times it was as if his desire to succeed had pulled him through the water like a rope. Wiping seawater from the neck of the rucksack he removed several seals of waterproof tape and withdrew a tightly bound plastic bag. A few minutes later he had discarded his T-shirt and shorts and dressed himself in damp blue jeans, a black cotton shirt and dark sweater. On his feet he wore grey socks and the counterfeit tennis shoes from the market in Guangzhou.

Now I look like a typical Hong Kong Chinese. Now if they stop me I can say that I am out here watching for birds.

Wang removed the binoculars from his rucksack and the small, poorly bound volume on egrets posted to him from Beijing three weeks earlier. The back of his throat was sour with the salt and pollutants of the sea and he drank greedily from a bottle of water, swallowing hard in an effort to remove them. Then he looped the binoculars around his neck, placed the water bottle back in the rucksack and waited for the sun.

2 (#ulink_ff4ed3be-034f-5865-89c0-ccddaf50f345)

Black Watch (#ulink_ff4ed3be-034f-5865-89c0-ccddaf50f345)

Lance Corporal Angus Anderson, 1st Battalion Black Watch, three months into the regiment’s final tour of Hong Kong, walked along the path from Luk Keng. This was magic hour, before the heat and the mosquitoes, before cockerels and barked orders and discipline punctured his private dream of Asia. Breathing the cool salt air, he slowed to an easy stroll as the first rays of the dawn sun began to heat the surrounding hills. One of only six Black Watch soldiers assigned to patrol the border in support of the Hong Kong Police, Anderson had been dispatched by an immigration inspector to make a brisk check of Starling Inlet before returning to headquarters for breakfast.

‘Sometimes they try to swim,’ the inspector had told him. His name was Leung. There were purple scars on his hands. ‘Sometimes they escape the sharks and the tide and make their way on foot to Tai Po.’

Anderson took out a cigarette. The sea was calm and he listened to the rhythm of the water, to the cry of a cormorant on the wind. He felt a strange, anarchic impulse to strip out of his uniform and to run, like a streaker at Murrayfield, down into the lukewarm freedom of the ocean. Six hours earlier he had helped to untangle a corpse from the coils of razor wire that stretched all along the land border from Deep Bay to Sha Tau Kok. His commanding officer called it ‘Chateau Cock’, like a bottle of cheap claret, and everybody in the battalion was expected to laugh. The body was that of a Chinese peasant girl wearing shorts and flip-flops and he could not erase from his memory the picture of her pale neck twisted into the fence and the blood from her arms which had turned brown in the sulphur glare of the floodlights. Would this kind of thing end after 30 June? Would the eye-eyes stop coming over? Leung had told them that in 1996 alone the Field Patrol Detachment had arrested more than 5,000 illegal immigrants, most of them young men looking for work in the construction industry in Hong Kong. That was about fourteen coming across every night. And now the FPD was facing a last-minute, pre-handover surge of Chinese nationals willing to risk the phalanx of armed police massed on both sides of the border in the slender hope of vanishing into the communities of Yuen Long, Kowloon and Shatin.

Anderson lit the cigarette. He couldn’t see the sense in chogies risking their lives for two months in what was left of British Hong Kong. There wouldn’t be an amnesty on eye-eyes; there wouldn’t be passports for the masses. Thatcher had seen to that. Christ, there were veterans of the Hong Kong Regiment, men sitting in one-bedroom flats in Kowloon who had fought for Winston bloody Churchill, who still wouldn’t get past immigration at Heathrow. Outsiders didn’t seem to realize that the colony was all but dead already. Rumour had it that Governor Patten spent his days just sitting around in Government House, counting down the hours until he could go home. The garrison was down to its last 2,000 men: everything from Land Rovers to ambulances, from coils of barbed wire to bits of old gym equipment, had been auctioned off. The High Island Training Camp at Sai Kung had been cleared and handed over to the People’s Liberation Army before Anderson had even arrived. In the words of his commanding officer, nothing potentially ‘sensitive’ or ‘hazardous’ could be left in the path of the incoming Chinese military or their communist masters, which meant Black Watch soldiers working sixteen-hour days mapping and documenting every fingerprint of British rule, 150 years of naval guns and hospitals and firing ranges, just so the chogies knew exactly what they were getting their hands on. Anderson had even heard stories about a submerged net running between Stonecutters Island and Causeway Bay to thwart Chinese submarines. How was the navy going to explain that one to Beijing?

A noise down on the beach. He dropped the cigarette and reached for his binoculars. He heard it again. A click of rocks, something moving near the water’s edge. Most likely an animal of some kind, a wild pig or civet cat, but there was always the chance of an illegal. To the naked eye Anderson could make out only the basic shapes of the beach: boulders, hollows, crests of sand. Peering through the binoculars was like switching off lights in a basement; he actually felt stupid for trying. Go for the torch, he told himself, and swept a steady beam of light as far along the coast as it would take him. He picked out weeds and shingle and the blue-black waters of the South China Sea, but no animals, no illegal.

Anderson continued along the path. He had another forty-eight hours up here, then five jammy days in Central raising the Cenotaph Union Jack at seven every morning, and lowering it again at six. That, as far as he could tell, was all that he would be required to do. The rest of the time he could hit the bars of Wan Chai, maybe take a girl up to the Peak or go gambling out at Macau. ‘Enjoy yourself,’ his father had told him. ‘You’ll be a young man thousands of miles from home living through a little piece of history. The sunset of the British Empire. Don’t just sit on your arse in Stonecutters and regret it that you never left the base.’

The light was improving all the time. Anderson heard a motorbike gunning in the distance and waved a mosquito out of his face. He was now about a mile from Luk Keng and able to pick out more clearly the contours of the path as it dropped towards the sea. Then, behind him, perhaps fifteen or twenty metres away, a noise that was human in weight and tendency, a sound that seemed to conceal itself the instant it was made. Somebody or something was out on the beach. Anderson swung round and lifted the binoculars, yet they were still no good to him. Touching his rifle, he heard a second noise, this time as if a person had toppled off balance. His pulse quickened as he scanned the shore and noticed almost immediately what appeared to be an empty petrol can lying on the beach. Beside it he thought he could make out a second container, perhaps a small plastic drum – had they been painted black? – next to a wooden pallet. So much debris washed up onshore that Anderson couldn’t be certain that he was looking at the remains of a raft. The men had been trained to look for flippers, clothing, discarded inner tubes, but the items here looked suspicious. He would have to walk down to the beach to check them for himself and, by doing so, run the risk of startling an eye-eye who might care more for his own freedom than he did for the life of a British soldier.

He was no more than twenty feet from the containers when a stocky, apparently agile man in his late forties poked his nose out of the trees and walked directly towards him, his hand outstretched like a bank manager.

‘Good morning, sir!’ Anderson levelled the rifle but lowered it in almost the same movement as his brain registered that it was listening to fluent English. ‘I am to understand from your uniform that you are a member of Her Majesty’s Black Watch. The famous red hackle. Your bonnet. But no kilt, sir! I am disappointed. What do they say? The kilt is the best clothes in the world for sex and diarrhoea!’ The chogie was shouting across the space between them and grinning like Jackie Chan. As he came crunching along the beach it looked very much to Anderson as though he wanted to shake hands. ‘The Black Watch is a regiment with a great and proud history, no? I remember the heroic tactics of Colonel David Rose at the Hook in Korea. I am Professor Wang Kaixuan at the university here, Department of Economics. Welcome to our island. It is a genuine pleasure to meet you.’

Wang had at last arrived. Anderson took an instinctive step back as the stranger came to a halt three feet away from him, planting his legs like a sumo wrestler. They did indeed shake hands. The chogie’s closely cropped hair was either wet or greasy; it was hard to tell.

‘Are you out here alone?’ Wang asked, looking lazily at the colouring sky as if to imply that the question carried no threat. Anderson couldn’t pick the broad face for northern Han or Cantonese, but the spoken English was impeccable.

‘I’m on patrol down here at the beach,’ he said. ‘And yourself?’

‘Me? I stayed in the area over the weekend. To take the opportunity to look for the egrets that are native to the inlet at this time of year. Perhaps you have seen one on your patrol?’

‘No,’ Anderson said. ‘I haven’t.’ He wouldn’t have known what an egret looked like. ‘Could you show me some form of identification, please?’

Wang managed to look momentarily offended. ‘Oh, I don’t carry that sort of thing.’ As if to illustrate the point, he made a show of frisking himself, patting his hands up and down his chest before securing them in his pockets. ‘It is a pity you have not seen an egret. An elegant bird. But you enjoy our surroundings, no? I am told – although I have never visited there myself – that the hills in this part of the New Territories are very similar in geographical character to certain areas of the Scottish Highlands. Is that correct?’

‘Aye, that’s probably true.’ Anderson was from Stranraer, a pan-flat town in the far south-west, but the comparison had been made many times before. ‘I’m sorry, sir. I can see that you’re carrying binoculars, I can see that you’re probably who you say you are, but I’m going to have to ask you again for a passport or driving licence. Do you not carry any form of identification?’

It was the moment of truth. Had Angus Anderson been a different kind of man – less certain of himself, perhaps more trusting of human behaviour – the decade of events triggered by Wang’s subsequent capture might have assumed an entirely different character. Had the professor been allowed, as he so desperately desired, to proceed unmolested all the way to Government House, the name of Joe Lennox might never have been uttered in the secret corridors of Shanghai and Urumqi and Beijing. But it was Wang’s misfortune that quiet April morning to encounter a sharp-eyed Scot who had rumbled him for a fake almost immediately. This chogie was no birdwatcher. This chogie was an illegal.

‘I have told you. I don’t usually carry any form of identification with me.’

‘Not even a credit card?’

‘My name is Wang Kaixuan, I am a professor of economics at the university here in Hong Kong. Please telephone the department switchboard if you feel uncertain. On a Wednesday morning my colleagues are usually at their desks by eight o’clock. I live at 71 Hoi Wang Road, Yau Ma Tei, apartment number 19. I can understand that the Black Watch regiment has an important job to do in these difficult months but I have lived in Hong Kong ever since I was a child.’

Anderson unclipped his radio. It would only take ten seconds to call in the sighting. He seemed to have no other option. This guy was a conman, using tactics of questions and bluster to throw him off the scent. Leung’s unit could be down in a police patrol boat before seven o’clock. Let them sort it out.

‘Nine, this is One Zero, over.’

Wang now had a choice to make: sustain the lie, and allow the soldier to haul him in front of Immigration, which carried the risk of immediate deportation back to China, or make a move for the radio, engendering a physical confrontation with a Scotsman half his age and almost twice his height. In the circumstances, it felt like no choice at all.

He had knocked the radio out of Anderson’s hand before the soldier had time to react. As it spun into the sand Anderson swore and heard Wang say, ‘I am sorry, I am sorry,’ as he stepped away. Something in this surrendering, apologetic gesture briefly convinced him not to strike back. For some time the two men stared at one another without speaking until a crackled voice in the sand said: ‘One Zero, this is Nine. Go ahead, over,’ and it became a case of who would blink first. Anderson bent down, keeping his eyes on Wang all the time, and retrieved the radio as if picking up a revolver from the ground. Wang looked at the barrel of Anderson’s rifle and began to speak.

‘Please, sir, do not answer that radio. All I am asking is that you listen to me. I am sorry for what I did. Tell them it was a mistake. I beg you to tell them you have resolved your problem. Of course I am not who I say I am. I can see that you are an intelligent person and that you have worked this out. But I am asking you to deal with me correctly. I am not a normal person who swims across the inlet in the middle of the night. I am not an immigrant looking for a job. I do not want citizenship or refugee status or anything more or less than the attention of the British governor in Hong Kong. I am carrying with me information of vital importance to Western governments. That is all that I can tell you. So please, sir, do not answer that radio.’

‘I have to answer.’ Anderson was surprised to hear a note of conciliation in his voice. The encounter had taken on a surreal quality. How many Chinese mainlanders pitched up on a beach at 6 a.m. talking about David Rose at the Hook in fluent, near-accentless English? And how many of them claimed to have political intelligence that required a meeting with Chris Patten?

‘What kind of information?’ he asked, amazed that he had not already jammed Wang’s wrists into a set of PlastiCuffs and marched him up the beach. Again the voice said, ‘One Zero, this is Nine. Please go ahead, over,’ and Anderson looked back across the water at the pale contours of China, wondering what the hell to do. A fishing boat was edging out into the bay. Wang then turned his head to stare directly into Anderson’s eyes. He wanted to convey the full weight of responsibility which now befell him.

‘I have information about a very senior figure in Beijing,’ he said. ‘I have information about a possible high-level defection from the Chinese government.’

3 (#ulink_47f8476c-4673-5d75-892c-4274491ed8e6)

Lennox (#ulink_47f8476c-4673-5d75-892c-4274491ed8e6)

Joe Lennox left Jardine House at seven o’clock that evening, nodded discreetly at a French investment banker as he sank two vodka and tonics at the Captain’s Bar of the Mandarin Oriental, hailed a cab on Connaught Road, made his way through the rush-hour traffic heading west into the Mid-Levels and walked through the door of Rico’s at precisely 8.01 p.m. It was a gift. He was always on time.

I was sitting towards the back of the restaurant drinking a Tsingtao and reading a syndicated article in the South China Morning Post about the prospect of a Labour victory in the forthcoming UK elections. A ginger-haired Canadian woman at the next table was eating crayfish and throwing out dirty looks because of the cigarette I was smoking. When she coughed and waved her hand in front of her face once too often, I stubbed it out. The air conditioning was on high and it felt as though everyone in the room was shivering.

Joe looked the way Joe always looked in those days: fit and undiminished, his characteristically inscrutable expression becoming more animated as he found my eyes across the room. At first glance, I suppose he was no different from any other decent-looking Jardine Johnnie in a Welsh & Jeffries suit, the sort who moves millions every day at Fleming’s and Merrill Lynch. That, I suppose, was the whole point about Joe Lennox. That was the reason they picked him.

‘Cold in here,’ he said, but he took his jacket off when he sat down. ‘What are you reading?’

I told him and he ventured a mildly critical opinion of the columnist – a former Tory cabinet minister – who had written the piece. (The next day I went through some cuttings and saw that the same grandee had been responsible for a couple of Patten-savaging articles in the British press, which probably explained Joe’s antagonism.) He ordered a Tsingtao for himself and watched as the Canadian woman put her knife and fork together after finishing the crayfish.

‘Been here long?’ he asked.

‘About ten minutes.’

He was wearing a dark blue shirt and his forearms were tanned from walking in the New Territories with Isabella the previous weekend. He took out a packet of cigarettes and leaned towards the Canadian to ask if she would mind if he smoked. She seemed so taken aback by this basic display of courtesy that she nodded her assent without a moment’s hesitation, then eyebrowed me as if I had been taught a valuable lesson in charm. I smiled and closed the Post.

‘It’s good to see you,’ I said.

‘You too.’

By this point we had been friends for the best part of a year, although it felt like longer. Living overseas can have that effect; you spend so much time socializing with a relatively small group of people that relationships intensify in a way that is unusual and not always healthy. Nevertheless, the experience of getting to know Joe had been one of the highlights of my brief stay in Hong Kong, where I had been living and working since the autumn of 1994. In the early days I was never certain of the extent to which that affection was reciprocated. Joe was an intensely loyal friend, amusing and intelligent company, but he was often withdrawn and emotionally unreadable, with a habit – doubtless related to the nature of his profession – of keeping people at arm’s length.

To explain how we met. In 1992 I was reporting on the siege of Sarajevo when I was approached at a press conference by a female SIS officer working undercover at the UN. Most foreign journalists, at one time or another, are sounded out as potential sources by the intelligence services. Some make a song and dance about the importance of maintaining their journalistic integrity; the rest of us enjoy the fact that a tax-free grand pops up in our bank account every month, courtesy of the bean-counters at Vauxhall Cross. Our Woman in Sarajevo took me to a quiet room at the airport and, over a glass or two of counterfeit-label Irish whiskey, acquired me as a support agent. Over the next couple of years, in Bosnia, Kigali and Sri Lanka, I was contacted by SIS and encouraged to pass on any information about the local scene that I deemed useful to the smooth running of our green and pleasant land. Only very occasionally did I have cause to regret the relationship.

Joe Lennox left school – expensive, boarding – in the summer of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. He was not an exceptional student, at least by the standards of the school, but left with three good A-levels (in French, Spanish and history), a place at Oxford and a private vow never to submit any children of his own to the peculiar eccentricities of the English private school system. Contemporaries remember him as a quiet, popular teenager who worked reasonably hard and kept a low profile, largely, I suspect, because Joe’s parents never lost an opportunity to remind their son of the ‘enormous financial sacrifices’ they had made to send him away in the first place.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, who went off to pick fruit in Australia or smoke weed for six months on Koh Samui, Joe didn’t take a gap year but instead went straight up to Oxford to study Mandarin as part of the BA Honours course at Wadham. Four years later he graduated with a starred First and was talent-spotted for Six in late 1993 by a tutor at the School of Oriental and African Studies, where he had gone to enquire about the possibility of doing a PhD. He went to a couple of interviews at Carlton Gardens, sailed through the Civil Service exams and had been positively vetted by the new year of 1994. Years later, Joe and I had dinner in London, when he began to speak candidly about those first few months as an Intelligence Branch officer.

‘Think about it,’ he said. ‘I was twenty-three. I’d known nothing but straitjacket British institutions from the age of eight. Prep school, public school, Wadham College Oxford. No meaningful job, no serious relationship, a year in Taiwan learning Mandarin, where everyone ate noodles and stayed in their offices until eleven o’clock at night. When the Office vetted me for the EPV I felt like a standing joke: no police record; no debts; no strong political views – these were the Major years, after all; a single Ecstasy tablet swallowed in a Leeds nightclub in 1991. That was it. I was a completely clean slate, tabula rasa. They could do with me more or less as they pleased.’

Vetting led to Century House, in the last months before the move to Vauxhall Cross. Joe was put into IONEC, the fabled initiation course for new MI6 recruits, alongside three other Oxbridge graduates (all male, all white, all in their thirties), two former soldiers (both Scots Guards, via Sandhurst) and a forty-year-old Welsh biochemist named Joanne who quit after six weeks to take up a $150,000-a-year position at MIT. On Joe’s first day, ‘C’ told the new intake that SIS still had a role to play in world affairs, despite the ending of the Cold War and the break-up of the Soviet Union. Joe specifically remembered that the Chief made a point, very early on, of emphasizing the importance of the ‘special relationship with our Cousins across the pond’ and of praising the CIA for its ‘extraordinary technical resources’, without which, it was implied, SIS would have been neutered. Joe listened, nodded and kept his head down, and within two months had been taken to the spook training centre at Fort Monckton, where he persuaded strangers in Portsmouth pubs to part with their passport numbers and learned how to fire a handgun. From the sources I’ve spoken to, it’s fairly clear that Joe, in spite of his age, was considered a bit of a star. Spies, declared or otherwise, usually operate from the safety of British embassies overseas, using diplomatic cover as a means of running agents in hostile territories. Very early on, however, it was suggested that Joe would be most effective working under non-official cover in Asia, at long-term, deniable length from the Service. It was certainly a feather in his cap. While his fellow IONEC officers were moved into desk jobs in London, analysing intelligence and preparing for their first postings overseas, the Far East Controllerate was finding Joe a job in Hong Kong, ostensibly working as a freight forwarder at Heppner Logistics, a shipping company based in Jardine House. In reality he was a NOC, operating under non-official cover, by far the most sensitive and secret position in the intelligence firmament.

Joe turned twenty-four on the day he touched down at Kai Tak. His parents had seen him off at Heathrow under the misguided impression that their beloved only son was leaving England to seek his fortune in the East. Who knew? Perhaps he’d be back in a few years with a foxy Cantonese wife and a grandchild to show off in the Home Counties. Joe felt awkward not telling his family and friends the truth about what he was up to, but Six had advised against it. It was better that way, they said. No point in making anyone worry. Yet I think there were additional factors at play here. Secrecy appealed to something in Joe’s nature, a facet of his personality that the spooks at Vauxhall Cross had recognized instantly, but which he himself had not yet fully come to understand. Lying to his parents felt like an act of liberation: for the first time in his life he was free of all the smallness and the demands of England. In less than a year Joe Lennox had cut himself off from everything that had made and defined him. Arriving in Hong Kong, he was born again.

Heppner Logistics was a tiny operation run out of two small offices on the eleventh floor of Jardine House, a fifty-two-storey edifice overlooking Victoria Harbour and dotted with tiny circular windows, an architectural anomaly which earned it the local nickname ‘The House of a Thousand Arseholes’. Ted Heppner was a former Royal Marine who emigrated to Hong Kong in 1972. For eighteen years he had facilitated the international shipment of ‘sensitive’ cargoes on behalf of SIS, but this was the first time that he had agreed to take on an intelligence officer as an employee. At first, Ted’s Singaporean wife Judy, who also functioned as his secretary, wasn’t keen on the idea, but when the Cross bought her a Chanel handbag and bumped up her salary by twenty per cent she embraced Joe like a long-lost son. Nominally he was required to show up every day and to field whatever faxes and phone calls came into the office from clients looking to move freight consignments around the world, but in reality Ted and Judy continued to deal with over ninety-five per cent of Heppner business, leaving Joe free to carry out his work for Queen and Country. If anybody asked why an Oxford graduate with a starred First in Mandarin was earning less than £20,000 a year working for a logistics company in Hong Kong, Joe told them that he’d been involved in a failed business venture back home and had just wanted to get the hell out of London. If they continued to pry, he hinted that he saw Heppner’s as a short-term option which would allow him, within six or eight months, to apply for a job with one of the larger Taipan conglomerates, such as Swire’s or Jardine Matheson.

It was illustrative of the extreme sensitivity of Joe’s position that Ted and Judy were two of only a handful of people who knew that Joe was under non-official cover. The others included David Waterfield, Head of Station for SIS in Hong Kong, Waterfield’s second-in-command, Kenneth Lenan, and Rick Zagoritis, a legendary figure in the Far East Controllerate who acted as Joe’s mentor and go-between in the first few months of his posting. I became aware of his activities when Zagoritis was obliged to fly to London for medical reasons in the autumn of 1995. Up to that point, Rick had been my SIS handler. As a result of an article I had written for the Sunday Times Magazine about Teochiu triad heroin dealers, London had become interested in the contacts I had made in the criminal underworld and I had provided Zagoritis with detailed assessments of the structure and intentions of triad groups in the Pearl River Delta. With Rick gone, I needed a new handler.

That was when Joe stepped in. It was a considerable challenge for such a junior player, but he proved a more than competent replacement. Within less than a year of arriving in the colony, he had made a name for himself as a highly effective NOC. Nor were there any concerns about his private life. In two reports commissioned by Kenneth Lenan as routine checks into the behaviour of new recruits, Joe demonstrated himself to be surprisingly self-disciplined when confronted by the myriad opportunities for hedonism which are part and parcel of male expat life in Asia. (‘He’ll learn,’ Waterfield muttered glumly. ‘He’ll learn.’) Nor was he troubled by the paranoia and duplicity of his double life. One of the more potent myths of the secret world, put about by spy writers and journalists and excitable TV dramas, is that members of the intelligence community struggle constantly with the moral ambiguity of their trade. This may be true of a few broken reeds, most of whom are quietly shown the door, but Joe lost little sleep over the fact that his life in Hong Kong was an illusion. He had adjusted easily to the secret existence, as if he had found his natural vocation. He loved the work, he loved the environment, he loved the feeling of playing a pivotal role in the covert operations of the state. About the only thing that was missing in his life was a woman.

4 (#ulink_5fbe62ea-baaf-5be4-a167-c19583bf31d2)

Isabella (#ulink_5fbe62ea-baaf-5be4-a167-c19583bf31d2)

Isabella Aubert arrived at the restaurant at about twenty-past eight. The first indication that she had entered the room came with a simultaneous movement from two male diners sitting near the entrance, whose heads jerked up from their bowls of soup and then followed her body in a kind of dazed, nodding parabola as she swayed between the tables. She was wearing a black summer dress and a white coral necklace that seemed to glow under the lights against her tanned skin. Joe must have picked up on the crackle in the room because he pushed his chair back from the table, stood up and turned to face her. Isabella was smiling by now, first at me, then at Joe, checking around the restaurant to see if she recognized anyone. Joe kissed her only briefly on the cheek before she settled into the chair next to mine. Physically, in public, they were often quite formal together, like a couple who had been married for five or ten years, not two twenty-six-year-olds in only the second year of a relationship. But if you spent time around Joe it didn’t take long to realize that he was infatuated with Isabella. She dismantled his instinctive British reserve; she was the one thing in his life that he could not control.

‘Hi,’ she said. ‘How are you, Will?’ Our little hug of greeting went wrong when I aimed a kiss at her cheek that slid past her ear.

‘I’m fine,’ I replied. ‘You?’

‘Hot. Overworked. Late.’

‘You’re not late.’ Joe reached out to touch her hand. Their fingers mingled briefly on the table before Isabella popped her napkin. ‘I’ll get you a drink.’

They had met in December 1995, on Joe’s first visit back to the UK from Hong Kong, when he had been an usher at a wedding in Hampshire. Isabella was a friend of the bride’s who had struggled to keep a straight face while reading from ‘The Prophet’ during the service. ‘Like sheaves of corn he gathers you unto himself,’ she told the assembled congregation. ‘He sifts you to free you from your husks. He grinds you to whiteness.’ At one point Joe became convinced that the beautiful girl at the lectern in the wide-brimmed hat was looking directly at him as she said, ‘He kneads you until you are pliant. And then he assigns you to his sacred fire, that you may become sacred bread for God’s sacred feast,’ but it was probably just a trick of the light. At that moment, most of the men in the church were labouring under a similar delusion. Afterwards Isabella sought him out at the pre-dinner drinks, walking towards him carrying a glass of champagne and that hat, which had lost its flower.

‘What happened?’ he said.

‘Dog,’ she replied, as if that explained everything. They did not leave one another’s side for the next two hours. At dinner, seated at separate tables, they made naked eyes across the marquee as a farmer complained to Isabella about the iniquities of the Common Agricultural Policy while Joe told a yawning aunt on his left that freight forwarding involved moving ‘very large consignments of cargo around the world in big container ships’ and that Hong Kong was ‘the second busiest port in Asia after Singapore’, although ‘both of them might soon be overtaken by Shanghai’. As soon as pudding was over he took a cup of coffee over to Isabella’s table and sat at a vacant chair beside hers. As they talked, and as he met her friends, for the first time he regretted having joined SIS. Not because the life required him to lie to this gorgeous, captivating girl, but because within four days he would be back at his desk on the other side of the world drafting CX reports on the Chinese military. Chances are he would never see Isabella again.

Towards eleven o’clock, when the speeches were done and middle-aged fathers in red trousers had begun dancing badly to ‘Come on Eileen’, she simply leaned across to him and whispered in his ear, ‘Let’s go.’ Joe had a room at a hotel three miles away but they drove back along the M40 to Isabella’s flat in Kentish Town, where they stayed in bed for two days. ‘We fit,’ she whispered when she felt his naked body against hers for the first time, and Joe found himself adrift in a world that he had never known: a world in which he was so physically and emotionally fulfilled that he wondered why it had taken him so long to seek it out. There had been girlfriends before, of course – two at Oxford and one just a few days after he had arrived in Hong Kong – but with none of them had he experienced anything other than the brief extinguishing of a lust, or a few weeks of intense conversations about the Cultural Revolution followed by borderline pointless sex in his rooms at Wadham. From their first moments together Isabella intrigued and fascinated him to the point of obsession. He confessed to me that he was already planning their lives together after spending just twenty-four hours in her flat. Joe Lennox had always been a decisive animal, and Joe Lennox had decided that he was in love.

On the Monday night he drove back to his hotel in Hampshire, settled the bill, returned to London and took Isabella for dinner at Mon Plaisir, a French restaurant he loved in Covent Garden. They ate French onion soup, steak tartare and confit of duck and drank two bottles of Hermitage Cave de Tain. Over balloons of Delamain – he loved it that she treated alcohol like a soft drink – Isabella asked him about Hong Kong.

‘What do you want to know?’ he said.

‘Anything. Tell me about the people you work with. Tell me what Joe Lennox does when he gets up in the morning.’

He was aware that the questions formed part of an ongoing interview. Should I share my life with you? Do you deserve my future? Not once in the two days they had spent together had the subject of the distance that would soon separate them been broached with any seriousness. Yet Joe felt that he had a chance of winning Isabella round, of persuading her to leave London and of joining him in Hong Kong. It was fantasy, of course, not much more than a pipe dream, but something in her eyes persuaded him to pursue it. He did not want what they had shared to be thrown away on account of geography.

So he would paint a picture of life in Hong Kong that was vivid and enticing. He would lure her to the East. But how to do so without resorting to the truth? It occurred to him that if he told Isabella that he was a spy, the game would probably be over. Chances were she would join him on the next flight out to Kowloon. What girl could resist? But honesty for the NOC was not an option. He had to improvise, he had to work around the lie.

‘What do I do in the morning?’ he said. ‘I drink strong black coffee, say three Hail Marys and listen to the World Service.’

‘I’d noticed,’ she said. ‘Then what?’

‘Then I go to work.’

‘And what does that involve?’ Isabella had long, dark hair and it curled across her face as she spoke. ‘Do you have your own office? Do you work down at the docks? Are there secretaries there who lust after you, the quiet, mysterious Englishman?’

Joe thought about Judy Heppner and smiled. ‘No, there’s just me and Ted and Ted’s wife, Judy. We’re based in a small office in Central. If I was to tell you the whole story you’d probably disintegrate with boredom.’

‘Are you bored by it?’

‘No, but I definitely see it as a stepping stone. If I play my cards right there’ll be jobs that I can apply for at Swire’s or Jardine Matheson in a year or six months, something with a bit more responsibility, something with better pay. After university, I just wanted to get the hell out of London. Hong Kong seemed to fit the bill.’

‘So you like it out there?’

‘I love it out there.’ Now he had to sell it. ‘I’ve only been away a few months but already it feels like home. I’ve always been fascinated by the crowds and the noise and the smells of Asia, the chaos just round the corner. It’s so different to what I’ve grown up with, so liberating. I love the fact that when I leave my apartment building I’m walking out into a completely alien environment, a stranger in a strange land. Hong Kong is a British colony, has been for over ninety years, but in a strange way you feel we have no place there, no role to play.’ If David Waterfield could hear this, he’d have a heart attack. ‘Every face, every street sign, every dog and chicken and child scurrying in the back streets is Chinese. What were the British doing there all that time?’

‘More,’ Isabella whispered, looking at him over her glass with a gaze that almost drowned him. ‘Tell me more.’

He stole one of her cigarettes. ‘Well, at night, on a whim, you can board the ferry at Shun Tak and be playing blackjack at the Lisboa Casino in Macau within a couple of hours. At weekends you can go clubbing in Lan Kwai Fong or head out to Happy Valley and eat fish and chips in the Members Enclosure and lose your week’s salary on a horse you never heard of. And the food is incredible, absolutely incredible. Dim sum, char siu restaurants, the freshest sushi outside of Japan, amazing curries, outdoor restaurants on Lamma Island where you point at a fish in a tank and ten minutes later it’s lying grilled on a plate in front of you.’

He knew that he was winning her over. In some ways it was too easy. Isabella worked all week in an art gallery on Albemarle Street, an intelligent, overqualified woman sitting behind a desk eight hours a day reading Tolstoy and Jilly Cooper, waiting to work her charms on the one Lebanese construction billionaire who just happened to walk in off the street to blow fifty grand on an abstract oil. It wasn’t exactly an exciting way of spending her time. What did she have to lose by moving halfway round the world to live with a man she barely knew?

She took out a cigarette of her own and cupped Joe’s hand as he lit it. ‘It sounds incredible,’ she said, but suddenly her face seemed to contract. Joe saw the shadow of bad news colour her eyes and felt as if it was all about to slip away. ‘There’s something I should have told you.’

Of course. This was too much of a good thing for it to end any other way. You meet a beautiful woman at a wedding, you find out she’s terminally ill, married, or moving to Istanbul. The wine and the rich food swelled up inside him and he was surprised by how anxious he felt, how betrayed. What are you going to tell me? What’s your secret?

‘I have a boyfriend.’

It should have been the hammer blow, the deal-closer, and Isabella was instantly searching Joe’s face for a reaction. Somehow she managed to assemble an expression that was both obstinate and ashamed at the same time. But he found that he was not as surprised as he might have been, discovering a response to her confession which was as smart and effective as anything he might have mustered in his counter-life as a spy.

‘You don’t any more.’

And that sealed it. A stream of smoke emerged from Isabella’s lips like a last breath and she smiled with the pleasure of his reply. It had conviction. It had style. Right now that was all she was looking for.

‘It’s not that simple,’ she said. But of course it was. It was simply a question of breaking another man’s heart. ‘We’ve been together for two years. It’s not something I can just throw away. He needs me. I’m sorry I didn’t tell you about him before.’

‘That’s OK,’ Joe said. I have lied to you, so it’s only fair that you should have lied to me. ‘What’s his name?’

‘Anthony.’

‘Is he married?’

This was just a shot in the dark, but by coincidence he had stumbled on the truth. Isabella looked amazed.

‘How did you know?’

‘Instinct,’ he said.

‘Yes, he is married. Or was.’ Involuntarily she touched her face, covering her mouth as if ashamed by the role she had played in this. ‘He’s separated now. With two teenage children…’

‘… who hate you.’

She laughed. ‘Who hate me.’

In the wake of this, a look passed between them which told Joe everything that he needed to know. So much of life happens in the space between words. She will leave London, he thought. She’s going to follow me to the East. He ran his fingers across Isabella’s wrists and she closed her eyes.

That night, drunk and wrapped in each other’s bodies in the Christmas chill of Kentish Town, she whispered: ‘I want to be with you, Joe. I want to come with you to Hong Kong,’ and it was all he could do to say, ‘Then be with me, then come with me,’ before the gift of her skin silenced him. Then he thought of Anthony and imagined what she would say to him, how things would end between them, and Joe was surprised because he felt pity for a man he had never known. Perhaps he realized, even then, that to lose a woman like Isabella Aubert, to be cast aside by her, would be something from which a man might never recover.

5 (#ulink_1d970598-0df1-552b-af1a-1c002a566966)

The House of a Thousand Arseholes (#ulink_1d970598-0df1-552b-af1a-1c002a566966)

Waterfield wasn’t happy about it.

Closing the door of his office, eight floors above Joe’s in Jardine House, he turned to Kenneth Lenan and began to shout.

‘Who the fuck is Isabella Aubert and what the fuck is she doing flying eight thousand miles to play houses with RUN?’

‘RUN’ was the cryptonym the Office used for Joe to safeguard against Chinese eyes and ears. The House of a Thousand Arseholes was swept every fourteen days, but in a crowded little colony of over six million people you never knew who might be listening in.

‘The surname is French,’ Lenan replied, ‘but the passport is British.’

‘Is that right? Well, my mother had a cat once. Siamese, but it looked like Clive James. I want her checked out. I want to make sure one of our best men in Hong Kong isn’t about to chuck in his entire career because some agent of the DGSE flashed her knickers at him.’

The ever-dependable Lenan had anticipated such a reaction. As a young SIS officer in the sixties, David Waterfield had seen careers crippled by Blake and Philby. His point of vulnerability was the mole at the heart of the Service. Lenan consoled him.

‘I’ve already taken care of it.’

‘What do you mean, you’ve already taken care of it?’ He frowned. ‘Is she not coming? Have they split up?’

‘No, she’s coming, sir. But London have vetted. Not to the level of EPV, but the girl looks fine.’

Lenan removed a piece of paper from the inside pocket of his jacket, unfolded it and began to improvise from the text: ‘Isabella Aubert. Born Marseilles, February 1973. Roman Catholic. Father Eduard Aubert, French national, insurance broker in Kensington for most of his working life. Womanizer, inherited wealth, died of cancer ten years ago, aged sixty-eight. Mother English, Antonia Chapman. ‘‘Good stock’’, I think they call it. Worked as a model before marrying Aubert in 1971. Part-time artist now, never remarried, lives in Dorset, large house, two Labradors, Aga, etcetera. Isabella has a brother, Gavin, both of them privately educated, Gavin at Radley, Isabella at Downe House. The former lives in Seattle, gay, works in computer technology. Isabella spent a year between school and university volunteering at a Romanian orphanage. According to one friend the experience ‘‘completely changed her’’. We don’t exactly know how or why at this stage. She didn’t adopt one of the children, if that’s the point the friend was getting at. Then she matriculates at Trinity Dublin in the autumn of ’92, hates it, drops out after six weeks. According to the same friend she now goes ‘‘off the rails for a bit’’, heads out to Ibiza, works on the door at a nightclub for two summers, then meets Anthony Charles Ellroy, advertising creative, at a dinner party in London. Ellroy is forty-two, mid-life crisis, married with two kids. Leaves his wife for Isabella, who by now is working for a friend of her mother’s at an art gallery in Green Park. Would you like me to keep going?’

‘Ibiza,’ Waterfield muttered. ‘What’s that? Ecstasy? Rave scene? Have you checked if she’s run up a criminal record with the Guardia Civil?’

‘Clean as a whistle. A few parking tickets. Overdraft. That’s it.’

‘Nothing at all suspicious?’ Waterfield looked out of the window at the half-finished shell of IFC, the vast skyscraper, almost twice the height of the Bank of China, which would soon dominate the Hong Kong skyline. He held a particular affection for Joe and was concerned that, for all his undoubted qualities, he was still a young man possibly prone to making a young man’s mistakes. ‘No contact with liaison during this stint in Romania, for instance?’ he said. ‘No particular reason why she chucks in the degree?’

‘I could certainly have those things looked at in greater detail.’

‘Fine. Good.’ Waterfield waved a hand in the air. ‘And I’ll have a word with him when the dust has settled. Arrange to meet her in person. What does she look like?’

‘Pretty,’ Lenan said, with his typical gift for understatement. ‘Dark, French looks, splash of the English countryside. Good skin. Bit of mystery there, bit of poise. Pretty.’

6 (#ulink_db6ac71e-d745-5ce7-b8f1-c4057d4ad83c)

Cousin Miles (#ulink_db6ac71e-d745-5ce7-b8f1-c4057d4ad83c)

It wasn’t a bad description, although it didn’t capture Isabella’s smile, which was often wry and mischievous, as if she had set herself from a young age to enjoy life, for fear that any alternative approach would leave her contemplating the source of the melancholy that ebbed in her soul like a tide. Nor did it suggest the enthusiasm with which she embraced life in those first few weeks in Hong Kong, aware that she could captivate both men and women as much with her personality as with her remarkable physical beauty. For such a young woman, Isabella was very sure of herself, perhaps overly so, and I certainly heard enough catty remarks down the years to suggest that her particular brand of self-confidence wasn’t to everyone’s taste. Lenan, for example, came to feel that she was ‘vain’ and ‘colossally pleased with herself’, although, like most of the stitched-up Brits in the colony, given half a chance he would have happily whisked her off to Thailand for a dirty weekend in Phuket.

At the restaurant that night I thought she looked a little tired and Joe and I did most of the talking until Miles arrived at about half-past eight. He was wearing chinos and flip-flops and carrying an umbrella; from a distance it looked as though his white linen shirt was soaked through with sweat. On closer inspection, once he’d shaken our hands and sat himself down next to Joe, it became clear that he had recently taken a shower and I laid a private bet with myself that he’d come direct from Lily’s, his favourite massage parlour on Jaffe Road.

‘So how’s everybody doing this evening?’

The presence of this tanned, skull-shaved Yank with his deep, imposing voice lifted our easygoing mood into something more dynamic. We were no longer three Brits enjoying a quiet beer before dinner, but acolytes at the court of Miles Coolidge of the CIA, waiting to see where he was going to take us.

‘Everybody is fine, Miles,’ Joe said. ‘Been swimming?’

‘You’re smelling that?’ he said, looking down at his shirt as a waft of shower gel made its way across the table. Isabella leaned over and did a comic sniff of his armpits. ‘Just came from the gym,’ he said. ‘Hot outside tonight.’

Joe stole a glance at me. He knew as well as I did of Miles’s bi-weekly predilection for hand jobs, although it was something that we kept from Isabella. None of us, where girls were concerned, wanted to say too much about the venality of male sexual behaviour in the fleshpots of Hong Kong. Even if you were innocent, you were guilty by association of gender.

Did it matter that Miles regarded Asia as his own personal playground? I have never known a man so rigorous in the satisfaction of his appetites, so comfortable in the brazenness of his behaviour and so contemptuous of the moral censure of others. He was the living, breathing antithesis of the Puritan streak in the American character. Miles Coolidge was thirty-seven, single, answerable to very few, the only child of divorced Irish-American parents, a brilliant student who had worked two jobs while studying at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service, graduating summa cum laude in 1982 and applying almost immediately for a position with the Central Intelligence Agency. Most of his close friends in Hong Kong – including myself, Joe and Isabella – knew what he did for a living, though we were, of course, sworn to secrecy. He had worked, very hard and very effectively, in Angola, Berlin and Singapore before being posted to Hong Kong at almost the exact same time as Joe. He spoke fluent Mandarin, workable Cantonese, a dreadful, Americanized Spanish and decent German. He was tall and imposing and possessed that indefinable quality of self-assurance which draws beautiful women like moths to a flame. A steady procession of jaw-dropping girls – AP journalists, human rights lawyers, UN conference attendees – passed through the revolving door of his apartment in the Mid-Levels and I would be lying if I said that his success with women didn’t occasionally fill me with envy. Miles Coolidge was the Yank of your dreams and nightmares: he could be electrifying company; he could be obnoxious and vain. He could be subtle and perceptive; he could be crass and dumb. He was a friend and an enemy, an asset and a problem. He was an American.

‘You know what really pisses me off?’ The waitress had brought him a vodka and tonic and handed out four menus and a wine list. Joe was the only person to start looking at them while Miles began to vent his spleen.

‘Your guy Patten. I talked to some of his people today. You know what’s going on down there at Government House? Nothing. You’ve got three months left before this whole place gets passed over to the Chinese and all anybody can think about is removals trucks and air tickets home and how they can get to kiss ass with Prince Charles at the handover before he boards the good ship Rule Britannia.’

This was vintage Coolidge: a blend of conjecture, hard facts and nonsense, all designed to wind up the Brits. Dinner was never going to be a sedate affair. Miles lived for conflict and its resolution in his favour and took a particular joy in Joe’s inability fully to argue issues of state in the presence of Isabella. She knew absolutely nothing about his work as a spy. At the same time, Waterfield had made Miles conscious of RUN back in 1996 as a result of blowback on a joint SIS/CIA bugging operation into the four candidates who were standing for the post of Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. That had created a nasty vacuum in the relationship between the four of us, and Miles was constantly probing at the edges of Joe’s cover in a way that was both childish and very dangerous.

It is worth saying something more about the relationship between the two of them, which became so central to events over the course of the next eight years. In spite of all that he had achieved, there is no question in my mind that Miles was jealous of Joe: jealous of his youth, his background as a privileged son of England, of the apparent ease with which he had earned a reputation as a first-rate undercover officer after just two years in the job. Everything that was appealing about Joe – his decency, his intelligence, his loyalty and charm – was taken as a personal affront by the always competitive Coolidge, who saw himself as a working-class boy made good whose progress through life had been stymied at every turn by an Ivy League/WASP conspiracy of which Joe would one day almost certainly become a part. This was nonsense, of course – Miles had risen far and fast, in many cases further and faster than Agency graduates of Princeton, Yale and Harvard – but it suited him to bear a grudge and the prejudice gave his relationship with Joe a precariousness which ultimately proved destructive.

Of course there was also Isabella. In cities awash with gorgeous, ego-flattering local girls, it is difficult to overstate the impact that a beautiful Caucasian woman can have on the hearts and souls of Western men in Asia. In her case, however, it was more than just rarity value; all of us, I think, were a little in love with Isabella Aubert. Miles concealed his obsession for a long time, in aggression towards her as well as wild promiscuity, but he was always, in one way or another, pursuing her. Joe’s possession of Isabella was the perpetual insult of Miles’s time in Hong Kong. That she was Joe’s girl, the lover of an Englishman whom he admired and despised in almost equal measure, only made the situation worse.

‘When you say ‘‘Patten’s people’’,’ I asked, ‘who exactly do you mean?’

Miles rubbed his neck and ignored my question. He was usually wary of me. He knew that I was smart and independent-minded but he needed my connections as a journalist and therefore kept me at the sort of length which hacks find irresistible: expensive lunches, covered bar bills, tidbits of sensitive information exchanged in the usual quid pro quo. We were, at best, very good professional friends, but I suspected – wrongly, as it turned out – that the minute I left Hong Kong I would probably never hear another word from Miles Coolidge ever again.

‘I mean, what exactly has that guy done in five years as governor?’

‘You’re talking about Patten now?’ Joe’s head was still in the menu, his voice uninflected to the point of seeming bored.

‘Yeah, I’m talking about Patten. Here’s my theory. He comes here in ’92, failed politician, can’t even hold down a job as a member of parliament; his ego must be going crazy. He thinks, ‘‘I have to do something, I have to make my mark. The mansion and the private yacht and the gubernatorial Rolls-Royce aren’t doing it for me. I have to be The Man.’’’

Isabella was laughing.

‘What’s funny?’ Joe asked her, but he was smiling too.

‘Guber what?’ she said.

‘‘‘Gubernatorial’’. It means ‘‘of the government’’. A gift of office. Jesus. I thought your parents gave you guys an expensive education?’

‘Anyway…’ Joe said, encouraging Miles to continue.

‘Anyway, so Chris is sitting there in Government House watching TV, maybe he’s arguing with Lavender over the remote control, Whisky and Soda are licking their balls’ – Lavender was Patten’s wife, Whisky and Soda their dogs. Miles got a good laugh for this – ‘and he says to himself, ‘‘How can I really mess this thing up? How can I make the British government’s handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China the biggest political and diplomatic shitstorm of modern times? I know. I’ll introduce democracy. After ninety years of colonial rule in which none of my predecessors have given a monkey’s ass about the six million people who live here, I’m gonna make sure China gives them a vote.’’ ’

‘Haven’t we heard this before?’ I said.

‘I’m not finished.’ There was just enough time for us to order some food and wine before Miles started up again. ‘What’s always really riled me about that guy is the hypocrisy, you know? He’s presented himself as this Man of the People, a stand-up guy from the sole remaining civilized nation on the face of the earth, but you really think he wanted democracy for humanitarian reasons?’

‘Yes I do.’ The firmness of Joe’s interjection took us all by surprise. To be honest, I had assumed he wasn’t listening. ‘And not because he enjoyed making waves, not because he enjoyed thumbing his nose at Beijing, but because he was doing his job. Nobody is saying that Chris Patten is a saint, Miles. He has his vanities, he has his ego, we all do. But in this instance he was brave and true to his principles. In fact it amazes me that people still question what he tried to do. Making sure that the people of Hong Kong enjoy the same quality of life under the Chinese government that they’ve enjoyed under British rule for the past ninety-nine years wasn’t a particularly bold strategy. It was just common sense. It wasn’t just the right thing to do morally; it was the only thing to do, politically and economically. Imagine the alternative.’

Isabella did a comic beam of pride and grabbed Joe’s hand, muttering, ‘Join us after this break, when Joe Lennox tackles world poverty…’

‘Oh come on.’ Miles drained his vodka and tonic as if it were a glass of water. ‘I love you, man, but you’re so fucking naïve. Chris Patten is a politician. No politician ever did anything except for his own personal gain.’

‘Are all Americans this cynical?’ Isabella asked. ‘This deranged?’

‘Only the stupid ones,’ I replied, and Miles threw a chewed olive stone at me. Then Joe came back at him.

‘You know what, Miles?’ He lit a cigarette and pointed it like a dart across the table. ‘Ever since I’ve known you you’ve been delivering this same old monologue about Patten and the Brits and how we’re all in it for the money or the personal gain or whatever argument you’ve concocted to make yourself feel better about the compromises you make every day down at the American embassy. Well call me naïve, but I believe there is such a thing as a decent man and Patten is the closest thing you’re going to get to it in public life.’ The arrival of our starters did nothing to deflect Joe from the task he had set himself. Miles pretended to be enthralled by his grilled prawns, but all of us knew he was about to get pummelled. ‘It’s time I put you out of your misery. I don’t want to come off sounding like a PR man for Chris Patten, but pretty much all of the commitments made to the people of Hong Kong five years ago have been fulfilled by his administration. There are more teachers in schools, more doctors and nurses in hospitals, thousands of new beds for the elderly. When Patten got here in ’92 there were sixty-five thousand Cantonese living in slum housing. Now there are something like fifteen thousand. You should read the papers, Miles, it’s all in there. Crime is down, pollution is down, economic growth up. In fact the only thing that hasn’t changed is people like you bitching about Patten because he got in the way of you making a lot of money. I mean isn’t that the argument? Appeasement? Isn’t that the standard Sinologist line on China? Don’t upset the suits in Beijing. In the next twenty years they’ll be in charge of the second biggest economy in the world. We need them onside so we can build General Motors factories in Guangdong, investment banks in Shenzhen, sell Coca-Cola and cigarettes to the biggest market the world has ever known. What’s a few votes in Hong Kong or a guy getting his fingernails ripped out by the PLA if we can get rich in the process? Isn’t that the problem? Patten has given you a conscience.’

Joe gave this last word real spit and venom and all of us were a little taken aback. It wasn’t the first time that I had seen him really go at Miles for the lack of support towards Patten shown by Washington, but he had never done so in front of Isabella and it felt as though two or three tables were listening in. For a while we just picked at our food until the argument regained its momentum.

‘Spoken like a true patriot,’ Miles said. ‘Maybe you’re too good for freight forwarding, Joe. Ever thought about applying for a job with the Foreign Office?’

This was water off a duck’s back. ‘What are you trying to say, Miles?’ Joe said. ‘What’s that chip telling you on your shoulder?’

This was one of the reasons Miles liked Joe: because he took him on; because he bullied the bully. He was smart enough to pick apart his arguments and not be daunted by the fact that Miles’s age and experience vastly outweighed his own.

‘I’ll tell you what it’s telling me. It’s telling me that you’re confusing a lot of different issues.’ Things were a little calmer now and we were able to eat while Miles held forth. ‘Patten pissed off a lot of people in the business community, here and on both sides of the Atlantic. This is not just an American phenomenon, Joe, and you know it. Everybody wants to take advantage of the Chinese market – the British, the French, the Germans, the fuckin’ Eskimos – because, guess what, we’re all capitalists and that’s what capitalists do. Capitalism drove you here in your cab tonight. Capitalism is going to pay for your dinner. Christ, Hong Kong is the last outpost of the British Empire, an empire whose sole purpose was to spread capitalism around the globe. And having a governor of Hong Kong with no experience of the Orient parachuting in at the last minute trying to lecture a country of 1.3 billion people about democracy and human rights – a country, don’t forget, that could have had this colony shut down in a weekend at any point over the past hundred years – well, that isn’t the ideal way of doing business. If you want to promote democracy, the best way is to open up markets and engage with politically repressed countries at first hand so that they have the opportunity to see how Western societies operate. What you don’t do is lock the stable door after the horse has not only bolted, but found itself another stable, redecorated, and settled down with a really fuckin’ hot filly in a meaningful relationship.’ Joe shook his head but we were all laughing. ‘And to answer your accusation that my government didn’t have a conscience until Chris Patten came along, all I can say is last time I checked we weren’t the ones willingly handing over six million of our own citizens to a repressive communist regime twenty miles away.’

It wasn’t a bad retort and Isabella looked across at Joe, as if concerned that he was going to let her down. I tried to intervene.

‘Confucius has been through all of this before,’ I said. ‘“The superior man understands what is right; the inferior man understands what will sell.’’ ’

Isabella smiled. ‘He also said, ‘‘Life is very simple. It’s men who insist on making it complicated.’’ ’

‘Yeah,’ said Miles. ‘Probably while getting jerked off by a nine-year-old boy.’

Isabella screwed up her face. ‘If you ask my opinion – which I notice none of you are doing – both sides are as bad as each other.’ Joe turned to face her. ‘The British often act as though they were doing the world a favour for the last three hundred years, as if it was a privilege to be colonized. What everybody always seems to forget is that the empire was a money-making enterprise. Nobody came to Hong Kong to save the natives from the Chinese. Nobody colonized India because they thought they needed railways. It was all about making money.’ Miles had a gleeful look on his face. Seeing this, Isabella turned to him. ‘You Yanks are no better. The only difference, probably, is that you’re more honest about it. You’re not trying to pretend that you care about human rights. You just get on with doing whatever the hell you want.’

All of us tried to jump in, but Miles got there first. ‘Look. I remember Tiananmen. I’ve seen the reports on torture in mainland China. I realize what these guys are capable of and the compromises we’re making in the West in order to –’

Joe was pulled out of the conversation by the pulse of his mobile phone. He removed it from his jacket pocket, muttered a frustrated: ‘Sorry, hang on a minute,’ and consulted the screen. The read-out said: ‘Percy Craddock is on the radio’, which was agreed code for contacting Waterfield and Lenan.

Isabella said, ‘Who is it, sweetheart?’

I noticed that Joe avoided looking at her when he replied. ‘Some kind of problem at Heppner’s. I have to call Ted. Give me two minutes, will you?’

Rather than speak on a cellphone, which could be hoovered by one of the Chinese listening stations in Shenzhen, Joe made his way to the back of the restaurant where there was a payphone bolted to the wall. He knew the number of the secure line by heart and was speaking to Lenan within a couple of minutes.

‘That was quick.’ Waterfield’s éminence grise sounded uncharacteristically chirpy.

‘Kenneth. Hello. What’s up?’

‘Are you having dinner?’

‘It’s OK.’

‘Alone?’

‘No. Isabella is here with Will Lasker. Miles, too.’

‘And how is our American friend this evening?’

‘Sweaty. Belligerent. What can I do for you?’

‘Unusual request, actually. Might be nothing in it. We need you to have a word with an eye-eye who came over this morning. Not blind flow. Claims he’s a professor of economics.’ ‘Blind flow’ was a term for an illegal immigrant coming south from China in the hope of finding work. ‘Everybody else is stuck at a black-tie do down at Stonecutters so the baton has passed to you. I won’t say any more on the phone, but there might be some decent product in it. Can you get to the flat in TST by ten-thirty?’

Lenan was referring to a safe house near the Hong Kong Science Museum in Tsim Sha Tsui East, on the Kowloon side. Joe had been there once before. It was small, poorly ventilated and the buzzer on the door had been burned by a cigarette. Depending on traffic, a taxi would have him there in about three-quarters of an hour. He said, ‘Sure.’

‘Good. Lee’s looking after him for now, but he’s refusing to speak to anyone not directly connected to Patten. Get Lee to fill you in when you get there. Apparently there’s already a file of some sort.’

Back in the dining area, Joe didn’t bother sitting down. He stood behind Isabella – almost certainly deliberately, so that he didn’t have to look at her – and put his hands on her shoulders as he explained that the bill of lading from a freight consignment heading to Central America had been lost in transit. It would have to be retyped and couriered to Panama before 2 a.m. Neither Miles nor myself, of course, believed this story for a minute, but we made a decent fist of saying, ‘Poor you, mate, what a nightmare,’ and ‘You’ll be hungry’ as Isabella kissed him and promised to be awake when he came home.

Once Joe had gone, Miles felt it necessary to polish off the lie and began a sustained diatribe against the phantom clients of Heppner Logistics.

‘I mean, what’s the matter with these people in freight? Bunch of fuckin’ amateurs. Some asshole on a ship can’t keep hold of a piece of paper? How tough is that?’

‘They work him so hard,’ Isabella muttered. ‘That’s the third time this month he’s been called back to the office.’

I was trying to think of ways of changing the subject when Miles chimed in again.

‘You’re right. You gotta guy there working hard, trying to climb the ladder from the bottom rung up, they’re always the ones who get treated badly.’ He was enjoying having Isabella more or less to himself. ‘But it can’t last. Joe is way too smart not to move onto bigger and better things. You have to stay positive, Izzy. Mah jiu paau, mouh jiu tiuh.’

‘What the hell does that mean?’

It was Cantonese. Miles was showing off.

‘Deng Xiaoping, honey. ‘‘The horses will go on running, the dancing will continue.’’ Anybody join me in another bottle of wine?’