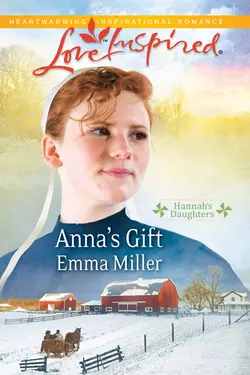

Anna′s Gift

Emma Miller

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Surprise ProposalIn Amish Country No one in Seven Poplars, Delaware, expects Anna Yoder ever to marry. Among her six pretty, petite sisters, big and plain Anna feels like a plow horse. But then Samuel Mast, the handsome widowed father she has secretly loved for years, asks if he can court her.Surely Anna has misheard—Samuel has his pick of lovely brides! She’s convinced he seeks a wife only as a mother for his five children. Or could a man like Samuel actually have a very romantic reason for wanting Anna by his side forever?Hannah’s Daughters: Seeking love, family and faith in Amish country.