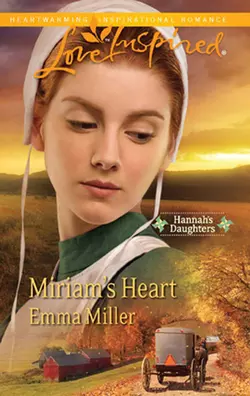

Miriam′s Heart

Miriam's Heart

Emma Miller

Miriam Yoder always thought she'd marry Charley Byler. Steady, dependable Charley, who grew up on the neighboring farm, and has been sweet on her since they were young.But then local veterinarian John Hartman catches Miriam's eye. He's handsome, charming, cares for animals–and is not Plain. While Miriam is known as the "wild" Yoder sister, she is still expected to marry a good Amish man. But what if it's God's plan to match her with John? Miriam must listen to her heart to truly know which man will claim her love and her future.

“I’m coming up,” Miriam said.

Charley offered his hand when she reached the top rung of the ladder. She took it and climbed up into the shadowy loft. Charley squeezed her fingers in his and she suddenly realized he was still holding her hand, or she was holding his; she wasn’t quite sure which it was.

She quickly tucked her hand behind her back and averted her gaze, as a small thrill of excitement passed through her.

“Miriam,” he began.

She backed toward the ladder. “I j-just wanted to see the hay,” she stammered, feeling all off-kilter. She didn’t know why, but she felt as if she needed to get away from Charley, as if she needed to catch her breath. “I’ve got things to do.”

Charley followed her down. Miriam felt her cheeks grow warm. She felt completely flustered and didn’t know why. She’d held Charley’s hand plenty of times before. What made this time different?

Charley was looking at Miriam strangely.

Something had changed between them in those few seconds up in the hayloft and Miriam wasn’t sure what.

EMMA MILLER

lives quietly in her old farmhouse in rural Delaware amid fertile fields and lush woodlands. Fortunate enough to be born into a family of strong faith, she grew up on a dairy farm, surrounded by loving parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Emma was educated in local schools, and once taught in an Amish schoolhouse much like the one at Seven Poplars. When she’s not caring for her large family, reading and writing are her favorite pastimes.

Miriam’s Heart

Emma Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Love comes from a pure heart and a

good conscience and a sincere faith.

—1 Timothy 1:5

For the lost Prince of Persia

and the blessings he has brought to our family

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Epilogue

Letter to Reader

Questions for Discussion

Chapter One

Kent County, Delaware—Early Autumn

“Whoa, easy, Blackie!” Miriam cried as the black horse slipped and nearly fell. The iron-wheeled wagon swayed ominously. Blackie’s teammate, Molly, stood patiently until the gelding recovered his footing.

Miriam let out a sigh of relief as her racing pulse returned to normal. She’d been driving teams since she was six, but Blackie was young and had a lot to learn. Gripping the leathers firmly in her small hands, Miriam guided the horses along the muddy farm lane that ran between her family’s orchard and the creek. The bank on her right was steep, the water higher than normal due to heavy rain earlier in the week.

“Not far now,” she soothed. Thank the Lord for Molly. The dapple-gray mare might have been past her prime, but she could always be counted on to do her job without any fuss. The wagon was piled high with bales of hay, and Miriam didn’t want to lose any off the back.

Haying was one of the few tasks the Yoder girls and their mother hadn’t done on their farm since Dat’s death two years ago. Instead, they traded the use of pasture land with Uncle Reuben for his extra hay. He paid an English farmer to cut and bale the timothy and clover. All Miriam had to do was haul the sweet-smelling bales home. Today, she was in a hurry. The sky suggested there was more rain coming out of the west and she had to get the hay stacked in the barn before the skies opened up. Not that she minded. In fact, she liked this kind of work: the steady clip-clop of the horses’ hooves, the smell of the timothy, the feel of the reins in her hands.

If Mam and Dat had had sons instead of seven daughters, Miriam supposed she’d have been confined to working in the house and garden like most Amish girls. But she’d always been different, the girl people called a tomboy, and she preferred outside chores. Despite her modest dress and Amish kapp, Miriam loved being in the fields in any weather and had a real knack with livestock. It might have been sinful pride, but when it came to farming, she secretly considered herself a match for any young man in the county.

It had been her father who’d taught her all she knew about planting and harvesting and rotating the crops. Her earliest memory was of riding on his wide shoulders as he drove the cows into the barn for milking. Since his death, she’d tried to fill his shoes, but his absence had left a great hole in their family and in her heart.

Miriam’s mother had taken over the teaching position at the Seven Poplars Amish school and all of Miriam’s unmarried sisters pitched in on the farm. It wasn’t easy, but they managed to keep the large homestead going, tending the animals, planting and harvesting crops and helping the less fortunate. All too soon, Miriam knew it would be harder. With Ruth marrying in November and going to live in the new house she and Eli were building on the far end of the property, there would be one less pair of hands to help.

Blackie’s startled snort and laid back ears yanked Miriam from her daydreaming. “Easy, boy. What’s wrong?” She quickly scanned the lane she’d been following that ran along a small creek. There wasn’t anything to frighten him, nothing but a weathered black stick lying between the wagon ruts.

But the gelding didn’t settle down. Instead, he stiffened, let out a shrill whinny and reared up in the traces, as the muddy branch came alive, raised its head, hissed threateningly and slithered directly toward Blackie.

Snake! Miriam shuddered as she came to her feet and fought to gain control of the terrified horses. She hated snakes. And this black snake was huge.

Blackie reared again, pawed the air and threw himself sideways, crashing into the mare and sending both animals and the hay wagon tumbling off the road and down the bank. A wagon wheel cracked and Miriam jumped free before she was caught in the tangle of thrashing horses, leather harnesses, wood and hay bales.

She landed in the road, nearly on top of the snake. Both horses were whinnying frantically, but for long seconds, Miriam lay sprawled in the mud, the wind knocked out of her. The black snake slithered across her wrist, making its escape and she squealed with disgust, and rolled away from it. Vaguely, she heard someone shouting her name, but all she could think of was her horses.

Charley Byler was halfway across the field from the Yoders’ barn when he saw the black horse rear up in its traces. He dropped his lunch pail and broke into a run as the team and wagon toppled off the side of the lane into the creek.

He was a fast runner. He usually won the races at community picnics and frolics, but he wasn’t fast enough to reach Miriam before she’d climbed up off the road and disappeared over the stream bank. “Ne!” he shouted. “Miriam, don’t!”

But she didn’t listen. Miriam—his dear Miriam—never listened to anything he said. Heart in his throat, Charley’s feet pounded the grass until, breathless, he reached the lane and half slid, half fell into the creek beside her. “Miriam!” He caught her shoulders and pulled her back from the kicking, flailing animals.

“Let me go! I have to—”

He caught her around the waist, surprised by how strong she was, especially for such a little thing. “Listen to me,” he pleaded. He knew how valuable the team was and how attached Miriam was to them, but he also knew how dangerous a frightened horse could be. His own brother had been killed by a yearling colt’s hoof when the boy was only eight years old. “Miriam, you can’t do it this way!”

Blackie, still kicking, had fallen on top of Molly. The mare’s eyes rolled back in her head so that only the whites showed. She thrashed and neighed pitifully in the muck, blood seeping from her neck and hindquarters to tint the creek water a sickening pink.

“You have to help me,” Miriam insisted. “Blackie will—”

At that instant, Charley’s boot slipped on the muddy bottom and they both went down into the waist-deep water.

To Charley’s surprise, Miriam—who never cried—burst into tears. He was helping her to her feet, when he heard the frantic barking of a dog. Irwin and his terrier appeared at the edge of the road.

“You all right?” Thirteen-year-old Irwin Beachy wasn’t family, but he acted like it since he’d come to live with the Yoders. He was home from school today, supposedly with a sore throat, but he was known to fib to get out of school. “What can I do?”

“I’m not hurt,” Miriam answered, between sobs. “Run quick…to the chair shop. Use the phone to…to call Hartman’s. Tell them…tell them it’s an emergency. We need a vet right away.”

Miriam started to shiver. Her purple dress and white apron were soaked through, her kapp gone. Charley thought Miriam would be better off out of the water, but he knew better than to suggest it. She’d not leave these animals until they were out of the creek.

“You want me to climb down there?” Irwin asked. “Maybe we could unhook the—”

“We might do more harm than good.” Charley looked down at the horses; they were quieter now, wide-eyed with fear, but not struggling. “I’d rather have one of the Hartmans here before we try that.”

“The phone, Irwin!” Miriam cried. “Call the Hartmans.”

“Ask for Albert, if you can,” Charley called after the boy as he took off with the dog on his heels. “We need someone with experience.”

“Get whoever can come the fastest!” Miriam pulled loose from Charley and waded toward the horses. “Shh, shh,” she murmured. “Easy, now.”

The dapple-gray mare lay still, her head held at an awkward angle out of the water. Charley hoped that the old girl didn’t have a broken leg. The first time he’d ever used a cultivator was behind that mare. Miriam’s father had showed him how and he’d always been grateful to Jonas and to Molly for the lesson. Since Miriam seemed to be calming Blackie, Charley knelt down and supported the mare’s head.

Blood continued to seep from a long scrape on the horse’s neck. Charley supposed the wound would need sewing up, but it didn’t look like something that was fatal. Her hind legs were what worried him. If a bone was shattered, it would be the end of the road for the mare. Miriam was a wonder with horses, with most any animal really, but she couldn’t heal a broken bone in a horse’s leg. Some people tried that with expensive racehorses, but like all Amish, the Yoders didn’t carry insurance on their animals, or on anything else. Sending an old horse off to some fancy veterinary hospital was beyond what Miriam’s Mam or the church could afford. When horses in Seven Poplars broke a leg, they had to be put down.

Charley stroked the dapple-gray’s head. He felt so sorry for her, but he didn’t dare to try and get the horses out of the creek until he had more help. If one of them didn’t have broken bones yet, the fright of getting them free might cause it.

Charley glanced at Miriam. One of her red-gold braids had come unpinned and hung over her shoulder. He swallowed hard. He knew he shouldn’t be staring at her hair. That was for a husband to see in the privacy of their home. But he couldn’t look away. It was so beautiful in the sunlight, and the little curling hairs at the back of her neck gleamed with drops of creek water.

A warmth curled in his stomach and seeped up to make his chest so tight that it was hard to breathe. He’d known Miriam Yoder since they were both in leading strings. They’d napped together on a blanket in a corner of his mother’s garden, as babies. Then, when they’d gotten older, maybe three or four, they’d played on her porch, swinging on the bench swing and taking all the animals out of a Noah’s Ark her Dat had carved for her and lining them up, two by two.

He guessed that he’d loved Miriam as long as he could remember, but she’d been just Miriam, like one of his sisters, only tougher. Last spring, he’d bought her pie at the school fundraiser and they’d shared many a picnic lunch. He’d always liked Miriam and he’d never cared that she was different from most girls, never cared that she could pitch a baseball better than him or catch more fish in the pond. He’d teased her, ridden with her to group sings and played clapping games at the young people’s doings.

Miriam was as familiar to him as his own mother, but standing here in the creek without her kapp, her dress soaked and muddy, scowling at him, he felt like he didn’t know her at all. He could have told any of his pals that he loved Miriam Yoder, but he hadn’t realized what that meant…until this moment. Suddenly, the thought that she could have been hurt when the wagon turned over, that she could have been tangled in the lines and pulled under, or crushed by the horses, brought tears to his eyes.

“Miriam,” he said. His mouth felt dry. His tongue stuck to the roof of his mouth.

“Yes?” She turned those intense gray eyes from the horse back to him.

He suddenly felt foolish. He didn’t know what he was saying. He couldn’t tell her how he felt. They hadn’t ridden home from a frolic together more than three or four times. They hadn’t walked out together and she hadn’t invited him in when they’d gotten to her house and everyone else was asleep. They’d been friends, chums; they ran around with the same gang. He couldn’t just blurt out that he suddenly realized that he loved her. “Nothing. Never mind.”

She returned her attention to Blackie. “Shh, easy, easy,” she said, laying her cheek against his nose. “He’s quieting down. He can’t be hurt bad, don’t you think? But where’s all that blood coming from?” She leaned forward to touch the gelding’s right shoulder, and the animal squealed and started struggling against the harness again.

“Leave it,” Charley ordered, clamping a hand on her arm. “Wait for the vet. You could get hurt.”

“Ne,” she argued, but it wasn’t a real protest. She didn’t struggle against his grip. She knew he was right.

He nodded. “Just keep doing what you were.” He held her arm a second longer than he needed to.

“Miriam!”

It was a woman’s voice, one of her sisters’, for sure. Charley released Miriam.

“Oh, Anna, come quick! Oh, it’s terrible.”

Charley glanced up. It was Miriam’s twin, a big girl, more than a head taller and three times as wide. No one could ever accuse Anna of not being Plain. She wasn’t ugly; she had nice eyes, but she couldn’t hold a candle to Miriam. Still, he liked Anna well enough. She had a good heart and she baked the best biscuits in Kent County, maybe the whole state.

“Don’t cry, Anna,” Miriam said. “You’ll set me to crying again.”

“How bad are they hurt?” Miriam’s older sister Ruth came to stand on the bank beside Anna. She was holding Miriam’s filthy white kapp. “Are you all right? Is she all right?” She glanced from Miriam to Charley.

“I’m fine,” Miriam assured her. “Just muddy. It’s Molly and Blackie I’m worried about.”

Fat tears rolled down Anna’s broad cheeks. “I’m glad Susanna’s not here,” she said. “I made her stay in the kitchen. She shouldn’t see this.”

“Did Irwin go to call the vet?” Charley asked. “We told him—”

“Ya.” Anna wiped her face with her apron. “He ran fast. Took the shortcut across the fields.”

“Is there anything I can do?” Ruth called down. “Should I come—?”

“Ne,” Miriam answered. “Watch for the vet. And send Irwin to the school to tell Mam as soon as he gets back.” The mare groaned pitifully, and Miriam glanced over at her. “She’ll be all right,” she said. “God willing, she will be all right.”

“I’ll pray for them,” Anna said. “That I can do.” She caught the corner of her apron and balled it in a big hand. “For the horses.”

Charley heard the dinner bell ringing from the Yoder farmhouse. “Maybe that’s Irwin,” he said to Miriam. “A good idea. We’ll need help to get the horses up.” The repeated sounding of the bell would signal the neighbors. Other Amish would come from the surrounding farms. There would be many strong hands to help with the animals, once it was considered safe to move them.

“There’s the Hartmans’ truck,” Ruth said. She waved, and Charley heard the engine. “I hope he doesn’t get stuck, trying to cross the field. The lane’s awfully muddy.”

Miriam looked at him, her eyes wide with hope. “It will be all right, won’t it, Charley?”

“God willing,” he said.

“It’s John,” Anna exclaimed. “He’s getting out of the truck with his bag.”

Great, Charley thought. It would have to be John and not his uncle Albert. He sighed. He supposed that John knew his trade. He’d saved the Beachys’ Jersey cow when everyone had given it up for dead. But once the Mennonite man got here, Miriam would have eyes only for John with his fancy education and his English clothes. Whenever John was around, he and Miriam put their heads together and talked like they were best friends.

“John must have been close by. Maybe it’s a good sign.” Miriam looked at him earnestly.

“Ya,” he agreed, without much enthusiasm. He knew that it was uncharitable to put his own jealousy before the lives of her beloved horses. “Ya,” he repeated. “It’s lucky he came so quick.” Lucky for Molly and Blackie, he thought ruefully, but maybe not for me.

Chapter Two

He’d witnessed a true blessing today, Charley thought as he watched John bandaging Blackie’s hind leg. Both animals had needed stitches and Molly had several deep cuts, but neither horse had suffered a broken bone. Between the sedative the young vet had administered and the help of neighbors, they’d been able to get the team back to the barn where they now stood in fresh straw in their stalls.

Charley had to admit that John knew what he was doing. He was ashamed of his earlier reluctance to have him come to the Yoder farm. With God’s help, both animals would recover. Even the sight of Miriam standing so close to John, listening intently to his every word, didn’t trouble Charley much. It was natural that Miriam would be worried about her horses and John was a very good vet. Reading anything more into it was his own insecurity. After all, John wasn’t Amish; he didn’t have a chance with Miriam. She would never choose a husband outside her faith.

Since she was a child, Miriam had had a gift for healing animals. When his Holstein calf had gotten tangled in a barbed wire fence, it had been ten-year-old Miriam who’d come every afternoon to rub salve on the calf’s neck while he held it still. Later that year, she’d helped his mother deliver twin lambs in a snowstorm, and the following summer Miriam had set a broken leg on his brother’s goat. More than one neighbor called on Miriam instead of the vet for trouble with their animals. Some men in the community seemed to forget she was a girl and asked her advice before they bought a cow or a driving horse.

If Miriam had been born English, Charley supposed that she might have gone to college to study veterinary medicine herself, but their people didn’t believe in that much schooling. For the Old Order Amish, eighth grade was the end of formal education. He’d been glad to leave school at fourteen, but for Miriam, it had been a sacrifice. She had a hunger to know more about animal doctoring, so it was natural that she and John would find a lot to talk about.

“I think we can fix the hay wagon, but a good third of the hay is wet through.”

“What?” Startled, Charley turned to see Eli standing beside him. He’d been so busy thinking about Miriam that he hadn’t even heard Eli enter the barn.

“The hay wagon,” Eli repeated. He glanced at John and Miriam and then cut his eyes at Charley, but he kept talking. “Front and back wheel on the one side need replacing, as well as some broken boards, but the axles are sound. We should be able to make it right in a few hours.”

Eli was sharp and not just with crafting wood. Charley could tell that he hadn’t missed the ease between Miriam and the Mennonite boy, or Charley’s unease at their friendship.

“Right.” Charley nodded. Eli was his friend and Ruth’s intended. Charley had been working on the foundation for their new house today. Otherwise, he wouldn’t have been at the Yoder place and close enough to reach Miriam when the accident happened. God’s mysterious ways, he thought, and then said to Eli, “Maybe we can get together some night after chores.”

“Ya,” Eli agreed with a twinkle in his eye. “No problem.”

“I don’t know what we would have done without you,” Miriam said to John as he opened the stall door for her. “When the hay wagon overturned, I was so afraid…”

Charley could hear the emotion in her voice. It made him want to walk over to her and put his arms around her. It made him want to protect her from anything bad that could ever happen to her. Instead, he stood there, feeling like a bumpkin, listening in on her and John’s conversation.

“You didn’t panic. That’s the most important thing with horses,” John said, speaking way too gently to suit Charley. “It’s a good thing you didn’t try to get them up without help. It could have been a lot worse if I hadn’t been able to sedate them.”

I’m the one who told Miriam to wait, Charley wanted to remind them. That was my decision. But again, he didn’t say what he was thinking. He knew he was being petty and that pettiness could eat a man up inside. How did the English refer to jealousy? A green-eyed monster?

Miriam looked over toward Charley, noticed him watching them and smiled, making his heart do a little flip. Why hadn’t he ever noticed how sweet her smile was?

“You were there when I needed you, too,” she said. “I was so scared. One of them could have been killed.”

I was terrified, but for you more than the horses. It seemed like it took an hour for me to run across the field to see if you were hurt. The words caught in his throat. He couldn’t spit them out, not in front of John and Eli. Usually, he had no trouble giving his opinion, flirting with girls, cracking jokes, being good-natured Charley, everybody’s friend. But not today…today he was as tongue-tied as Irwin.

He couldn’t tear his eyes away from Miriam. She was wearing a modest blue dress now, a properly starched kapp and a clean white apron. As soon as they’d gotten the horses out of the creek and headed back toward the barn, her sisters had rushed her to the house to put on dry clothes. The blue suited her. It was almost the color of a robin’s egg, without the speckles. Her red hair was freshly-combed and braided, pinned up and mostly hidden under her kapp, but he couldn’t help remembering how it had looked in the sunlight.

This morning, he’d been a bachelor, with no more thoughts of tying himself down in marriage any time soon than trying to fly off the barn roof. He’d certainly known that he’d have to get serious in a few years, and start a family, but not yet. He had years of running around to do yet—lots of girls to tease and frolics to enjoy. Now, in the time it took that wagon to overturn, his life had changed direction. After seeing Miriam this way today, he realized that what mattered most to him was winning her hand and having the right to watch her take her kapp off and brush out that red-gold hair every night.

Unconsciously, he tugged his wide-brimmed straw hat lower on his forehead, hoping no one would notice his embarrassment, but Miriam didn’t miss a trick. She reached up and pressed her hand to his cheek. The touch of her palm sent a jolt through him, and he jumped back, heat flashing under his skin. He was certain it made him look even more the fool.

“Charley Byler, what’s wrong with you?” she demanded. “You’re red as a banty rooster. And your clothes are still soaked. Are you taking a chill? You’d best come up to the house, and drink some hot coffee.”

“Can’t.” He backed off as if she were contagious. He couldn’t take the chance she’d touch him again. Not here. Not in front of the Mennonite. “Got to pick up Mary,” he said in a rush. “Thursdays. In Dover.” Every Thursday, his sister cleaned house for an English woman and his mother depended on him to bring her home. “She’ll be expecting me.”

“I forgot,” Miriam said. “That’s too bad. Mam and Anna are cooking an early supper, since we all missed our noon meal. I think they’ve been cooking since Mam got home from school. She wanted me to invite you and John to join us for fried chicken and dumplings. You’re welcome to bring Mary, too.”

“Ne.” He pushed his hat back. “Guess we’ll get home to evening chores.”

Shadows were lengthening in the big barn, but Miriam could read the disappointment on his face. She could tell he wanted to have dinner with them, so why didn’t he just come back after he picked up his sister? She didn’t know what was going on with Charley, but she could tell something was bothering him. She’d known him long enough to know that look on his face.

“Another time for certain,” Charley said, and fled the barn.

“Ya,” she called after him. “Another time.”

“Well, since Charley can’t come, maybe there’s room for me at the table,” Eli said.

She folded her arms, turning to him. “I didn’t think I had to invite you. You’re family. I bet Ruth’s already set a plate for you.” She smiled and he smiled back. Miriam was so happy for Ruth. Eli really did love her, and despite his rocky start in the community, he was going to make a good husband to her.

“Good,” Eli said, “because I’ve worked up such an appetite pulling those horses out of the creek, that I can eat my share and Charley’s, too.”

Eli lived with his uncle Roman and aunt Fannie near the chair shop where he worked as a cabinetmaker, but since he and Ruth had declared their intentions, he ate in the Yoder kitchen more evenings than not.

Miriam looked back at John expectantly. “Supper?”

“I don’t want to impose on your mother.” John knelt beside a bale of straw and closed up his medical case. “Uncle Albert is picking up something at the deli for—”

“You may as well give in,” Miriam interrupted. She rested one hand on her hip. “Mam won’t let you off the farm until she’s stuffed you like a Christmas turkey. We’re all grateful you came so quickly.”

John picked up the chest. “Then, I suppose I should stay. I wouldn’t want to upset Hannah.”

She chuckled, surprised he actually accepted her invitation, but pleased. She knew that he rarely got a home-cooked meal since he’d come to work with his grandfather and uncle in their veterinary practice. None of the three bachelors could cook. When he stopped by her stand at Spence’s, the auction and bazaar where they sold produce and baked goods twice a week, he always looked longingly at the lunch she brought from home. Sometimes, she took pity on him and shared her potato salad, peach pie, or roast beef sandwiches.

Blackie thrust his head over the stall door and nudged her, hay falling from his mouth. Miriam stroked his neck. “You’ve had a rough day, haven’t you, boy?” She took a sugar cube out of her apron pocket and fed it to him, savoring the warmth of his velvety lips against her hand. Then she walked back to check on Molly. The dapple-gray was standing, head down dejectedly, hind foot in the air, unwilling to put any weight on it. That was the hoof that she’d been treating for a stone bruise for the last week, and the thing that concerned John the most. He was afraid that the accident would now make the problem worse.

“Do you think I should stay with her tonight?” Miriam asked, fingering one of her kapp ribbons.

“Nothing more you can do now.” John moved to her side and looked at Molly. “She needs time for that sedative to wear off and then I can get a better idea of how much pain she’s in. I’ll come back and check on her again before I leave and I’ll stop by tomorrow. I need to see that the two of them are healing and I want to keep an eye on that hoof.”

“Supper’s ready!” Ruth pushed open the top of the Dutch door. “And bring your appetites. Mam and Anna have cooked enough food to feed half the church.”

“Charley had to pick up his sister in Dover so he left,” Miriam said, “but John and Eli have promised to eat double to make up for it.”

“Charley can’t eat with us?” Ruth pushed wide the bottom half of the barn door and stepped into the shadowy passageway. “That’s a shame.”

“Ya,” Miriam agreed. “A shame.” Ruth liked Charley. So did Anna, Rebecca, Leah, Johanna, Susanna and especially Mam. The trouble was, ever since the school picnic last spring, when Charley had bought her pie and they’d shared a box lunch, her sisters and Mam acted like they expected the two of them to be a couple. All the girls at church thought the two of them were secretly courting.

“Lucky for you that Charley was nearby when the wagon turned over,” Eli said. He and Ruth exchanged looks. “He’s a good man, Charley.”

Miriam glared at Ruth, who assumed an innocent expression. “It’s John you should thank,” Miriam said. “Without him, we might have lost both Molly and Blackie.”

“But Charley pulled you out of the creek.” Ruth followed Eli out into the barnyard. “He might have saved your life.”

Miriam could barely keep from laughing. “Charley’s the one who nearly drowned me. And the water isn’t deep enough to drown a goose.” She glanced back at John. “Pay no attention to either of them. Since they decided to get married, they’ve become matchmakers.”

“So, you and Charley?” John asked. “Are you—?”

“Ne!” she declared. “He’s like a brother to me. We’re friends, nothing more.” It was true. They were friends, nothing more and no amount of nudging by her family could make her feel differently. When the right man came along, she’d know it…if the right man came along. Otherwise, she was content staying here on the farm, doing the work she loved best and helping her mother and younger sisters.

Ruth led the way up onto the back porch where Miriam and the two men stopped at the outdoor sink to wash their hands. John looked at the large pump bottle of antibacterial soap and raised one eyebrow quizzically.

Miriam chuckled. “What did you expect? Lye soap?”

“No.” He grinned at her. “People just think that…”

“Amish live like George Washington,” she finished. Ruth and Eli were having a tug of war with the towel, but she ignored their silly game and met John’s gaze straight on. “We don’t,” she said. “We use all sorts of modern conveniences—indoor bathrooms, motor-driven washing machines, telephones.” She smiled mischievously. “We even have young, know-it-all Mennonite veterinarians.”

“Ouch.” He grabbed his middle and pretended to be in pain. Then, he shrugged. “Lots of people have strange ideas about my faith, too. My sister gets mistaken for being Amish all the time.”

“Because of her kapp,” Miriam agreed. “Tell her that I had an English woman at Spence’s last week ask me if I was Mennonite.”

“I’ll admit, I didn’t know much about you until I came here. I was surprised that the practice had so many Amish clients.” Eli tossed the towel to him and he offered it to her.

“Of course. We have a lot of animals.” She dried her hands and took a fresh towel off the shelf for him.

She liked John. He had a nice smile. He was a nice-looking young man. Nice, dark brown hair, cropped short in a no-nonsense cut, a straight nose and a good strong chin. Maybe not as pretty in the face as Eli, who was the most handsome man she’d ever seen, but almost as tall.

John was slim, rather than compact like Charley, with the faintest shadow of a dark beard on his cheeks. His fingers were long and slender; his nails clean and trimmed short. When he walked or moved his hands or arms, as he did when he hung the damp towel on the hook, he did it gracefully. John seemed like a gentle man with a quiet air of confidence and strength. It was one of the reasons she believed that he was so good with livestock and maybe why he made her feel so at ease when they were together.

“Miriam, John, come to the table,” Mam called through the screen door. “The food is hot.”

It wasn’t until then that Miriam noticed that Ruth and Eli had gone inside, while she and John had stood there woolgathering and staring at each other. Would he think her slow-witted, that it took her so long to wash the barn off her hands?

“Ya, we’re coming,” she answered. She pushed open the door for John, but he stopped and motioned for her to go through first. He was English in so many ways, yet not. John was an interesting person and she was glad he’d accepted Mam’s invitation to eat with them.

Her sisters, Irwin and Eli were already seated. Mam waved John to the chair at the head of the table, reserved for guests, since her father’s death. She took her own place between Ruth and her twin, Anna. Since John knew everyone but Anna and Susanna, she introduced them before everyone bowed their heads to say grace in silence.

Miriam hadn’t thought she was hungry, but just the smell of the food made her ravenous. Besides the chicken and dumplings, Mam and Anna had made broccoli, coleslaw, green beans and yeast bread. There were pickled beets, mashed potatoes and homemade applesauce. She glanced at John and noticed that his gaze was riveted on the big crockery bowl of slippery dumplings.

Mam asked Irwin to pass the chicken to John and the big kitchen echoed with the sound of clinking forks, the clatter of dishes and easy conversation. Susanna, youngest and most outspoken of her sisters, made Mam and Eli laugh when she screwed up her little round face and demanded to know where John’s hat was.

“My hat?” he asked.

“When you came in, you didn’t put your hat on the coatrack. Eli and Irwin put their hats on the coatrack. Where’s yours?”

Miriam was about to signal Susanna to hush, thinking she would explain later to her that unlike the Amish, Mennonite men didn’t have to wear hats. But then Irwin piped up. “Maybe Molly ate it.”

“Or Jeremiah,” Eli suggested, pointing to Irwin’s little dog, stretched out beside the woodstove.

“Or Blackie,” Anna said.

“Maybe he lost it in the creek,” Ruth teased.

John smiled at Susanna. “Nope,” he said. “I think a frog stole it when we were pulling the horses out.”

“Oh,” Susanna replied, wide-eyed.

John was teasing Susanna, but it was easy for Miriam to see that he wasn’t poking fun at her. He was treating her just as he would Anna or Ruth, if he knew them better. Sometimes, because Susanna had been born with Down syndrome, people didn’t know how to act around her. She was a little slow to grasp ideas or tackle new tasks, but no one had a bigger heart. It made Miriam feel good inside to see John fitting in so well at their table, almost as if the family had known him for years.

“We won’t forget what you did for the horses,” Mam said. “Even if they did eat your hat.”

Everyone laughed at that and Susanna laughed the loudest. It was the best ending to a terrible day that Miriam could ask for, and by the time John had finished his second slice of apple pie, she was sure that he had enjoyed his meal with them as much as they’d enjoyed his company.

Later, after she and John and Ruth and Eli had inspected the horses, John drove away in his pickup. He had one final house call before calling it a day. Eli left as well, wanting to clean the chair shop for his uncle. That left Miriam and Ruth to do the milking. Irwin drove the cows in and offered to help, but Miriam sent him off to see if Mam needed anything. Irwin was shaping up to be a good gardener, but he didn’t know the first thing about milking and usually ended up getting kicked by a cow or spilling a bucket of milk.

Miriam looked forward to this time of day. She and Ruth had always been close friends and soon Ruth would be in her own home with her own cow to milk. Miriam would miss her. She loved her twin Anna dearly; she loved all her sisters, but Ruth was the kind of big sister she could talk to about anything. Of course there were some nights when Miriam might have preferred to milk alone.

“You know he’s sweet on you,” Ruth said. She was milking a black-and-white Holstein cow named Bossy in the next stall. Ruth had her head pushed into Bossy’s sagging middle and two streams of milk hissed into her bucket in a steady rhythm.

“Who likes me?” Miriam stopped a few feet from Bossy’s tail, her empty bucket in one hand and a three-legged milking stool in the other. She’d tied a scarf over her kapp to keep it clean and pushed back her sleeves.

“Charley. He’s going to make someone a fine husband.”

“I know he is. It’s just not going to be me.” Miriam sighed and walked to the next stall where Polly, a brown Jersey, waited patiently, chewing her cud. “And I’m tired of you and Anna trying to make something of it that isn’t.”

“You like the cute vet better?”

Polly swished her tail and Miriam pushed it out of the way as she placed her stool on the cement floor and sat down. “John?”

“Was there another cute vet at supper?”

“He came because we needed him. It’s his job.”

“Ya, but you like him.” Ruth’s voice was muffled by the cow’s belly. “Admit it.”

Miriam took a soapy cloth and carefully washed Polly’s bag. The cow swished her tail again. Miriam dropped the cloth into the washbasin and took hold of one teat. She squeezed and pulled gently and milk squirted into the bucket. “First Charley, then John.”

“He’s Mennonite,” Ruth said.

“I know he’s Mennonite.”

“But you think he’s cute.”

Miriam wished her sister was standing close enough to squirt with a spray of milk. Once Ruth started, there was no stopping her. “Mam invited him to dinner, not me.”

“But you like him. Better than Charley.”

“Maybe I do and maybe I don’t,” she said. “But if you say another word about boys tonight, I’ll dump this bucket of milk over your head.”

It was dusk by the time John got back to the house that was both office and home for him, his grandfather and Uncle Albert. John completed his paperwork, refilled his portable medicine chest and went upstairs to shower. Once he’d changed into clean clothing, he wandered out onto the side porch where the two older men sat with their feet propped up on the rail, sipping tall glasses of lemonade. As always, the three shared the day’s incidents. When his grandfather asked, John began telling them about the accident at the Yoder farm.

The third time John mentioned Miriam’s name, his uncle Albert asked him if he was sweet on her. John shrugged and took a big sip of lemonade.

“She’s Old Order Amish,” his grandfather said.

“I know that,” John replied.

“Miriam, is she one of the twins?” his uncle asked.

“I think so.”

“The big one or the little one?”

“The little one.”

“Pretty as a picture,” Uncle Albert observed.

“Yeah,” John admitted, getting up and attempting a quick escape into the house before they pressed the issue any further.

Truth be told, he was sweet on Miriam Yoder and he was pretty certain she liked him. And it wasn’t just her looks or the physical chemistry between them that attracted him. She was easy to talk to and shared his love of animals. Although he always knew he would marry and have children someday, John hadn’t seriously dated since his final year of vet school, when his girlfriend of three years had broken up with him. Alyssa, the daughter of a Baptist minister, had broken his heart and after that he had filled in what little spare time he had with family. It had been so long that he had forgotten what it felt like to be so strongly attracted to a woman. The fact that Miriam was Amish complicated the matter even further.

His grandfather chuckled. “He’s sweet on her.”

“Good luck with that,” Uncle Albert said. “I’ve heard those Yoder girls can be a handful.”

John paused in the doorway and looked back. “Sometimes,” he said softly, “a handful is just the kind of woman a man is looking for.”

Chapter Three

Miriam and Anna were just setting the table for breakfast the following morning when they heard the sound of a wagon rumbling up their lane. Miriam, who’d showered after morning chores, snatched a kerchief off the peg and covered her damp hair before going to the kitchen door. “It’s Charley,” she called back as she walked out onto the porch. He reined in his father’s team at the hitching rail near the back steps.

“Morning.” The wagon was piled high with bales of hay.

“You’re up and about early,” she said, tucking as much of her hair out of sight as possible. Wet strands tumbled down her back, and she gave up trying to hide them. After all, it was only Charley.

“Where are you off to?” Behind her, Jeremiah yipped and hopped up and down with excitement. “Hush, hush,” she said to the dog. “Irwin! Call him. He’ll frighten Charley’s team.”

Irwin opened the screen door and scooped up the little animal. “Morning, Charley,” he said.

Charley climbed down from the wagon. “I’m coming here,” he said as he tied the horses to the hitching rail. “Here.”

“What?” she asked. Curious, Irwin followed her down the porch steps into the yard, the whining dog in his arms.

Charley laughed. “You wanted to know where I was going, didn’t you?”

She wrinkled her nose. “I don’t understand. We didn’t buy any hay from your father.”

“Ne.” He grinned at her. “But you lost a lot of your load in the creek. My Dat and Samuel and your uncle Reuben wanted to help.”

She sighed. The hay she’d lost had already been paid for. There was no extra money to buy more. “It’s good of you,” she said, “but our checking account—”

“This is a gift to help replace what you lost.”

“All that?” Irwin asked. “That’s a lot.”

She looked at the wagon, mentally calculating the number of bales stacked on it. “We didn’t have that much to begin with,” she said, “and not all our bales were ruined.”

Charley tilted his straw hat with an index finger and chuckled. “Don’t be so pigheaded, Miriam. I’m putting this in your barn. You’ll take it with grace, or explain to your uncle Reuben, the preacher, why you cannot accept a gift from the members of your church who love you.”

Moisture stung the back of her eyelids, and a lump rose in her throat. “Ya,” she managed. “It is kind of you all.”

Charley had always been kind. Since she’d been a child, she’d known that she could always count on him in times of trouble. When her father had died, without being asked Charley had taken over the chores and organized the young men to set up tables for supper after the funeral and carry messages to everyone in the neighborhood. A good man…a pleasant-looking man—even if he did usually need a haircut. But he’s just not the man I’d want for a husband, she thought, recalling her conversation with Ruth last night. Not for me, no matter what everyone else thinks.

He walked toward her, solid, sandy-haired Charley, bits of hay clinging to his pants and shirt, and pale blue eyes dancing. Pure joy of God’s good life, her father called that sparkle in some folks’ eyes. He was such a nice guy, perfect for a friend. Ruth was right, he would make someone a good husband; he would be perfect for sweet Anna. But Charley was a catch and he’d pick a cute little bride with a bit of land and a houseful of brothers, not her dear Plain sister.

“We’re family. We look out for our neighbors.”

She nodded, so full of gratitude that she wanted to hug him. This is what the English never saw, how they lived with an extended family that would never see one of their own do without.

“I’m happy to make the delivery and I’d not turn down a cup of coffee,” Charley said. “Or a sausage biscuit, if it was offered.” He gestured toward the house. “That’s Anna’s homemade sausage I smell, isn’t it? She seasons it better than the butcher shop.”

“Ya,” Irwin said. “It’s Anna’s sausage, fresh ground. And pancakes and eggs.”

Miriam laughed. “We’re just sitting down to breakfast. Would you like to join us?”

“Are Reuben’s sermons long?” Charley chuckled at his own jest as he brushed hay from his pants. “I missed last night’s supper. I’m not going to turn down a second chance at Anna’s cooking.” Then he glanced back toward the barn. “How are your horses?”

“Blackie’s stiff, but his appetite is fine. Molly’s no worse. I got her to eat a little grain this morning, but she’s still favoring that hoof. John said he’d stop by this afternoon.” She followed him up onto the porch and into the house. Irwin and the dog trailed after them.

“Miriam invited me to breakfast,” Charley announced as he entered the kitchen, leaving his straw hat on a peg near the door.

Mam rose from her place. “It’s good to have you.”

“He brought us a load of hay,” Miriam explained, grabbing a plate and extra silverware before sitting down. She set the place setting beside hers and scooted over on the bench to make room for him. “A gift from Uncle Reuben, Samuel and Charley’s father.”

Ruth smiled at him as she passed a plate of buckwheat pancakes to their guest. “It’s good of you. Of all who thought of us.”

“I mean to spread those bales that got wet,” Charley explained, needing no further invitation to heap his plate high with pancakes. “If the rain holds off, it could dry out again. I wouldn’t give it to the horses, but for the cows—”

“We could rake it up and pile it loose in the barn when it dries,” Miriam said, thinking out loud. “That could work. It’s a good idea.”

“A good idea,” Susanna echoed.

The clock on the mantel chimed the half hour. “Ach, I’ll be late for school,” Mam exclaimed. She took another swallow of coffee and got to her feet. When Charley started to rise, she waved him back. “Ne, you eat your fill. It’s my fault I’m running late. The girls and I were chattering like wrens this morning and I didn’t watch the time. Come, Irwin. There will be no excuses of illness today.”

Irwin popped up, rolling his last bit of sausage into a pancake and taking it with him.

“It wouldn’t do for the teacher to be late.” Anna collected Mam’s and Irwin’s dinner buckets and handed them out. “Have a good day.”

“Good day,” Irwin mumbled through a mouthful of sausage and pancake as he dodged out the door. “Watch Jeremiah, Susanna!”

“I will,” she called after him, obviously proud to be given such an important job every day. “He’s a good dog for me,” she announced to no one in particular.

“Don’t forget to meet me at the school after dinner with the buggy.” Mam tied her black bonnet under her chin. “Since there’s only a half day today, we’ve plenty of time to drive to Johnson’s orchard.”

“I won’t,” Miriam answered. Their neighbor, Samuel Mast, who was sweet on Mam, had loaned them a driving horse until Blackie recovered from his injuries. They’d have apples ripe in a few weeks here on the farm, but Mam liked to get an early start on her applesauce and canned apples. The orchard down the road had several early varieties that made great applesauce.

Once their mother was out the door, they continued the hearty meal. Miriam had been up since five and she suspected that Charley had been, too. They were all hungry and it would be hours until dinner. Having him at the table was comfortable; he was like family. Everyone liked him, even Irwin, who was rarely at ease with anyone other than her Mam and her sisters.

The only sticky moments of the pleasant breakfast were when Charley began to ask questions about John. “You say he’s coming back today?”

Miriam nodded. “The stitches need to stay in for a few days, but John wants to have a look at them today.”

“He thinks he has to look at ’em himself? You tell him you could do it? I know something about stitches. We both do.”

“He likes Miriam,” Susanna supplied, smiling and nodding. “He always comes and talks, talks, talks to her at the sale. And sometimes he buys her a soda—orange, the kind she likes. Ruffie says that Miriam had better watch out, because Mennonite boys are—”

“Hard workers,” Ruth put in.

Susanna’s eyes widened. “But that’s not what you said,” she insisted. “You said—”

Anna tipped over her glass, spilling water on Susanna’s skirt.

Susanna squealed and jumped up. “Oops.” She giggled. “You made a mess, Anna.”

“I did, didn’t I?” Anna hurried to get a dishtowel to mop up the water on the tablecloth.

“My apron is all wet,” Susanna announced.

“It’s fine,” Miriam soothed. “Eat your breakfast.” She rose to bring the coffeepot to the table and pour Charley another cup. “I heard your father had a tooth pulled last week,” she said, changing the conversation to a safer subject.

After they had eaten, Miriam offered to help Charley unload the hay, but he suggested she finish cleaning up breakfast dishes with her sisters. A load of hay was nothing to him, he said as he went out the door, giving Susanna a wink.

“What did I tell you?” Ruth said when the girls were alone in the kitchen. “People are beginning to talk about you and John Hartman, seeing you at the sale together every week. He’s definitely sweet on you, even Charley noticed.”

“I don’t see him at Spence’s every week,” Miriam argued.

Ruth lifted an eyebrow.

“So he likes to stop for lunch there on Fridays,” Miriam said.

“And visit with you,” Ruth said. “I’m telling you, he likes you and it’s plain enough that Charley saw it.”

“That’s just Charley. You know how he is.” Miriam gestured with her hand. “He’s…protective of us.”

“Of you,” Anna said softly.

“Of all of us,” Miriam insisted. “I haven’t done anything wrong and neither has John, so enough about it already.” She went into the bathroom and quickly braided her hair, pinned it up and covered it with a clean kapp.

When she came back into the kitchen, Anna was washing dishes and Susanna was drying them. Ruth was grating cabbage for the noon meal. “I’ve got outside chores to do so I’m going to go on out if you don’t need me in here,” Miriam said.

Ruth concentrated on the growing pile of shredded cabbage.

Miriam wasn’t fooled. “What? Why do you have that look on your face? You don’t believe me? John is a friend, nothing more. Can’t I have a friend?”

“Of course you can,” Ruth replied. “Just don’t do anything to worry Mam. She has enough on her mind. Johanna—” She stopped, as if having second thoughts about what she was going to say.

“What about Johanna?” Miriam didn’t think her sister Johanna had been herself lately. Johanna lived down the road with her husband and two small children, but sometimes they didn’t see her for a week at a time and that concerned Miriam. When she was first married, Johanna had been up to the house almost every day. Miriam knew her sister had more responsibilities since the babies had come along, but she sometimes got the impression Johanna was hiding something. “Are Jonah and the baby well?”

“Everyone is fine,” Anna said.

“Later,” Ruth promised, glancing meaningfully at Susanna. “I’ll tell you all I know, later.”

“I’ll hold you to it,” Miriam said. She thought about Johanna while she fed and watered the laying hens and the pigs. If no one was sick, what could the problem be? And why hadn’t Mam said anything to her about it? Once she’d finished up with the animals, she went to the barn to give Charley a hand.

Dat had rigged a tackle to a crossbeam and they used the system of ropes and pulleys to hoist the heavy hay bales up into the loft. It was hard work, but with two of them, it went quick enough. They talked about all sorts of things, nothing important, just what was going on in their lives: Ruth and Eli’s wedding, harvesting crops, the next youth gathering.

After sending the last bale up, Miriam walked to the foot of the loft ladder. Charley stood above her, hat off, wiping the sweat off his forehead with a handkerchief. “I’m coming up,” she said.

He moved back and offered his hand when she reached the top rung. She took it, climbed up into the shadowy loft and looked around at the neat stacks of hay. It smelled heavenly. It was quiet here, the only sounds the cooing of pigeons and Charley’s breathing. Charley squeezed her fingers in his and she suddenly realized he was still holding her hand, or she was holding his; she wasn’t quite sure which it was.

She quickly tucked her hand behind her back and averted her gaze, as a small thrill of excitement passed through her.

“Miriam,” he began.

She backed toward the ladder. “I just wanted to see the hay,” she stammered, feeling all off-kilter. She didn’t know why but she felt like she needed to get away from Charley, like she needed to catch her breath. “I’ve got things to do.”

“What you two doin’ up there?” Susanna called up the ladder. “Can I come up?”

“Ne! I’m coming down,” Miriam answered, descending the ladder so fast that her hands barely touched the rungs.

Charley followed her. He jumped off the ladder when he was three feet off the ground and landed beside her with a solid thunk.

“I came to see how Molly is.” Susanna looked at Miriam and then at Charley. “Something wrong?”

Miriam felt her cheeks grow warm. “Ne.” She brushed hay from her apron, feeling completely flustered and not knowing why. She’d held Charley’s hand plenty of times before. What made this time different? She could still feel the strength of his grip and wondered if this feeling of bubbly warmth that reached from her belly to the tips of her toes was temptation. No wonder handholding by unmarried couples was frowned upon by the elders.

“Ne,” Charley repeated. “Nothing wrong.” But he was looking at Miriam strangely.

Something had changed between them in those few seconds up in the hayloft and Miriam wasn’t sure what. She could hear it in Charley’s voice. She could feel it in her chest, the way her heart was beating a little faster than it should be.

Susanna was still watching her carefully. “Anna said to tell you to cut greens if you go in the garden and not to forget to meet Mam.”

The three stood there, looking at each other.

“Guess I should be going,” Charley finally said, awkwardly looking down at his feet.

“Thanks again for bringing the hay, Charley. I can always count on you.” Miriam dared a quick look into his eyes. “You’re like the brother I never had.”

“That’s me. Good old Charley.” He sounded upset with her and she had no idea why.

“Don’t be silly.” She tapped his shoulder playfully. “You’re a lifesaver. You kept me from drowning in the creek, didn’t you?”

“In the creek? Right, like you needed saving.” He laughed, and she laughed with him, easing the tension of the moment.

They walked out of the barn, side by side with Susanna trailing after them, and crossed the yard to the well. Charley drew up a bucket of water, and all three drank deeply from the dipper. Then he went back to the barn to guide the team and wagon down the passageway and out the far doors. By the time he’d turned his horses around and driven out of the yard, Miriam had almost stopped feeling as though she’d somehow let him down. Almost…

Later, in the buggy on the way to the orchard with her mother, Miriam had wanted to tell her about the strange moment in the hayloft with Charley. In a large family, even a loving one, time alone with parents was special. Miriam was a grown woman, but Mam had a way of listening without judging and giving sound advice without seeming to. Miriam valued her mother’s opinion more than anyone’s, even more than Ruth’s and the two of them were the closest among the sisters. But this afternoon, she didn’t want sisterly advice; she didn’t need any more of Ruth’s teasing about her friendship with John Hartman. Today, she needed her mother.

But before she could bring up Charley, she needed to find out what Ruth and Anna had been hinting about after breakfast, concerning Johanna. If Johanna had trouble, it certainly took priority over a silly little touch of a boy’s hand. She was just about to ask about her older sister when Mam gestured for her to pull over into the Amish graveyard and rein in the horse.

Sometimes, Mam came here to visit Dat’s grave, even though it wasn’t something that their faith encouraged. The graves were all neat and well cared for; that went without saying, but no one believed their loved ones were here. Those that had died in God’s grace abided with Him in heaven. Instead of mourning those who had lived out their earthly time, those left behind should be happy for them. But Mam—who’d been born and raised Mennonite—had her quirks and one of them was that she came here sometimes to talk to their father.

When Mam came to Dat’s grave, she usually came alone. This was different and Miriam gave her mother her full attention.

“You know we had a letter from Leah on Monday,” Mam said.

Miriam nodded. Her two younger sisters, Leah and Rebecca, had been in Ohio for over six months caring for their father’s mother and her sister, Aunt Jezebel. Grossmama had broken a hip falling down her cellar stairs a year ago, and although the bone had healed, her general health seemed to be getting worse. Aunt Ida, Dat’s sister, and her husband lived on the farm next to Grossmama, but her own constitution wasn’t the best, and she’d asked Mam for the loan of one of her girls. Mam had sent two, because neither Grossmama nor Aunt Jezebel, at their ages, could be expected to act as a proper chaperone for a young, unbaptized woman. No one, least of all Miriam, had expected the sisters to be away so long.

“What I didn’t tell you,” Mam continued, “was that this arrived on Tuesday from Rebecca.” She removed an envelope from her apron pocket. “You’d best read it yourself.”

Miriam slipped three lined sheets of paper out of the envelope and unfolded them. Rebecca’s handwriting was neat and bold. Her sister had wanted to follow their mother’s example and teach school. She’d gotten special permission from the bishop to continue her education by mail, but in spite of her sterling grades, no teaching positions in Amish schools had opened in Kent County.

Miriam skimmed over the opening and inquiries over Mam’s health to see what Mam was talking about. It wasn’t like her to keep secrets, and the fact that she hadn’t said anything about what was in the letter was out of the ordinary and disturbing.

As she read through the pages, Miriam quickly saw how serious the problem was. According to Rebecca, their grandmother had moved beyond forgetfulness and both sisters were concerned for her safety. Grossmama had never been an easy person to please, and Leah and Rebecca had been chosen to go because they were the best-suited to the job.

Dat had been their grandmother’s only son and she’d never approved of his choice of a bride. She’d made it clear from the beginning that she didn’t like Mam. Even as the years passed, she never missed an opportunity to find fault with her and her daughters. Miriam had always tried to remember her duty to her grandmother and to remain charitable when discussing her with her sisters, but the truth was, the prospect of Grossmama’s extended visit for Ruth’s marriage was something Miriam wasn’t looking forward to.

According to Rebecca’s letter, Grossmama had accidentally started fires in the kitchen twice. She’d taken to rising from her bed in the wee hours and wandering outside in her nightclothes, and was having unexplained bouts of temper, throwing objects at Leah and Rebecca and even at Aunt Jezebel. Grossmama had also begun to tell untruths about them to the neighbors. She refused to take her prescriptions because she was convinced that Aunt Jezebel was trying to poison her.

Miriam finished the letter and dropped it into her lap. “This is terrible,” she said. “What can we do?”

Mam’s eyes glistened with unshed tears. “I’ve been praying for an answer.”

Miriam closed her hand over her mother’s. “But why didn’t you tell us?”

“I’ve talked to your aunt Martha.”

“Aunt Martha?” If anyone could make a situation worse, it would be Dat’s sister. “And…”

“She is Grossmama’s daughter. I’m only a daughter-in-law,” Mam reminded her. “Anyway, Martha thinks that Rebecca may be exaggerating. She thinks we should go on as we are until they come here for the wedding.”

“While Grossmama burns down the house around my sisters?”

Mam laughed. “I hope it’s not that bad. As Rebecca says, she and Leah take turns keeping watch over her and they turn off the gas to the stove at night.”

“But why isn’t Aunt Martha or Aunt Ida or one of the other aunts doing something? She’s their mother!”

“And she was Jonas’s mother, my mother-in-law. God has blessed us, child. We’re better off financially than either of your aunts. Martha’s house is small and she’s already caring for Uncle Reuben’s cousin Roy. If your father was alive, he’d feel it was his duty to care for his mother. We can’t neglect that responsibility because he isn’t here, can we?”

“You mean Grossmama is coming to live with us?” Miriam couldn’t imagine such a thing. Her grandmother would destroy their peaceful home. She was demanding and so strict, she didn’t even want to see children playing on church Sundays. She objected to youth singings and frolics, and most of all, she couldn’t abide animals in the house. She would forbid Irwin to let Jeremiah through the kitchen door.

“Nothing is decided,” Mam said. “I spoke to Johanna on Tuesday evening. I meant to discuss it with the rest of you, but then you had the accident with the hay wagon and the time wasn’t right. I just wanted time alone to tell you about this.”

“Ruth doesn’t know?”

“We’ll share the letter with her when the time is right. She’s so excited about her wedding plans and the new house, I don’t want to spoil this special time for her. And Anna, well, you know how Anna is.”

“She’d look for the best in it,” Miriam conceded. “And she’d probably want to take a van out to Ohio tomorrow and make everything right for everyone.”

Her mother nodded. “You’re sensible, Miriam. And you have a good heart.”

“What do you need me to do, Mam?”

“For now? Pray. Think on this and look into your heart. If what Rebecca says is true, we may have to open our home to your grandmother. If we do, it must be all of us, with no hanging back. We have to do this together.”

“All right,” Miriam promised. Thoughts of Charley and the uncomfortable moment with him faded to the back of her mind. Her family—her mother—needed her. “But what shall we do right now?” she asked.

“Drive the horse to the orchard,” Mam said with a smile. “We’ll need those apples all the more with the wedding coming. We’ve got a lot of applesauce to make.”

“Grossmama hates cinnamon in her applesauce.”

“Does she?” Mam’s eyes twinkled with mischief. “And I was just thinking we should stop at Byler’s store to buy extra.”

Chapter Four

Early Saturday morning, two days after Miriam’s accident with the hay wagon, preparations began for Sunday church at Samuel Mast’s home. Anna, Ruth, Mam and Susanna joined Miriam and most of the other women of their congregation to make Samuel’s house ready for services and the communal meal that followed.

Since Samuel, the Yoders’ closest neighbor, was a widower, he had no wife to supervise the food preparation and cleaning. Neighbors and members of the community always came to assist the host before a church day and Samuel was never at a lack for help. It seemed to Miriam as if every eligible Amish woman in the county, or a woman with a daughter or sister of marrying age, turned out to bake, cook, scrub and sweep until Samuel’s rambling Victorian farmhouse shone like a new penny.

Miriam carried a bowl of potato salad in her right hand and one of coleslaw in her left as she crossed Samuel’s spacious kitchen to a stone-lined pantry beyond. Although the September day was warm, huge blocks of ice in soapstone sinks kept the windowless room cool enough to keep food fresh for the weekend. A large kerosene-driven refrigerator along one wall held a sliced turkey and two sliced hams, as well as a large tray of barbecued chicken legs. Pies and cakes, pickles, chowchows and jars of home-canned peaches weighed down shelves. The widower might not have been a great cook, but he never lacked for delicious food when it came to hosting church.

As Miriam exited the pantry, closing the heavy door carefully behind her, she nearly tripped over Anna, who was down on her hands and knees scrubbing the kitchen linoleum. At the sink, Ruth washed dishes and Johanna dried and put them away while Mam arranged a bouquet of autumn flowers on the oak table. “What can I do to help?” Miriam asked.

Anna dug another rag out of the scrub bucket, wrung it out and tossed it to her. Miriam caught the wet rag, frowning with exaggeration at her sister.

“You asked.” Anna grinned. She knew very well that Miriam’s strong point wasn’t housework, but she also knew that when it came down to it, her sister was a hard worker, no matter what the task.

Chuckling, Miriam got down to assist Anna in finishing the floor. Johanna, who had a good voice, began a hymn in High German, and Miriam, Anna and Ruth joined in. Miriam’s spirits lifted. Work always went faster with many hands and a light heart, and the words to the old song seemed to strike a chord deep inside her. It was strange how scrubbing dirty linoleum could make a person feel a part of God’s great plan.

Aunt Martha had taken over the downstairs living room and adjoining parlor, loudly directing her daughter Dorcas and several other young women in washing windows, polishing the wood floors and arranging chairs. But it didn’t take long for Johanna’s singing to spread through the house. Soon, Dorcas’s off-key soprano and Aunt Martha’s raspy tenor blended with the Yoder girls to make the walls ring with the joyful song of praise.

Samuel’s sister, Louise Stutzman, came down the steep kitchen staircase, leading Samuel’s daughter Mae, just as Johanna finished the chorus of their third hymn. The four-year-old was cranky, but Susanna, who’d come in the back door to find cookies, held out her arms and offered to take the little girl outside to play with the other small children.

“Gladly,” Louise said, ushering Mae in Susanna’s direction.

Susanna’s round face beamed beneath her white kapp. “Don’t worry. I’ll take good care of her.”

“I know you will, Susanna. All the children love you.”

Susanna nodded. “You can bring baby Mae to our libary. Mam says I am the best li-barian there is.”

“Librarian,” Mam corrected gently.

Susanna took a breath, grinned and repeated the word correctly. “Li-brarian!”

“Mam had our old milk house made into a lending library for the neighborhood,” Anna explained. “Susanna helps people find books to take home. And she goes with Miriam to buy new ones that the children will like.”

Louise smiled at Susanna. “That sounds like an important job.”

“It is!” Susanna proclaimed. “You come and see. I’ll find you a good book.” Anna held the door open and Susanna carried a now-giggling Mae outside.

“Susanna has such a sweet spirit,” Louise said. “You’ve been blessed, Hannah.”

“I know,” Mam agreed. “She’s very special to us.”

Miriam liked Samuel’s older sister. She was a jolly person with a big smile and a good heart. She was always patient and kind to Susanna, never assuming that because of her Down syndrome, Susanna was less than safe to be trusted with Mae.

Louise had come from Ohio on Friday and brought Mae along for a visit with her father. When Samuel’s wife died after a long illness, baby Mae was only a few months old. None of Samuel’s family thought that he could manage an infant, since he already had the twins, Peter and Rudy, Naomi and Lori Ann to care for. Reluctantly, Samuel had agreed to let his sisters keep the baby temporarily, with the understanding that when he remarried, Mae would rejoin the family. Louise had offered to take Lori Ann as well, but Samuel wouldn’t part with her.

Everyone thought that Samuel would marry after his year of mourning was up. And considering that he was the father of five, no one would have objected if he’d taken a new wife sooner. But it had been four years since Frieda had passed on, and Samuel seemed no closer to bringing a new bride home than he’d been on the day he’d ridden in the funeral procession to the graveyard.

Samuel made visits to his family in Ohio to see little Mae, and his mother and sisters brought the child to Delaware whenever it was his turn to host church services. The shared time was never very satisfactory for father or daughter. Mae was a difficult child, and Samuel and her sisters and brothers were strangers to her. The neighborhood agreed that the sooner Samuel took a wife and brought his family back together, the better for all.

The problem, as Miriam saw it, was that Samuel hadn’t shown any real interest in any of the marriageable young women in the county or those his sisters paraded before him in Ohio. Samuel Mast was a catch. He was a devout member of the church, had a prosperous farm and a pleasant disposition. And, he was a nice-looking man, strong and healthy and full of fun. No one could understand why he’d waited so long to remarry.

Miriam and the Yoder girls thought they knew why, though.

Despite the difference in their ages—Samuel was eight years younger than Mam—it looked to Miriam and her sisters as if Samuel liked their mother. She and Ruth had discussed the issue many times, usually late at night, when they were in bed. They both thought Samuel was a wonderful neighbor and a good man, but not the right husband for Mam.

Hannah had been widowed two years and, by custom, she should have remarried. The trouble was, she wasn’t ready, and neither were her daughters. Dat had been special and Miriam couldn’t see another man, not even Samuel, sitting at the head of the table and taking charge of their lives. Not yet at least.

Among the Plain people, a wife was supposed to render obedience to her husband. Not that she didn’t have a strong role in the family or in the household; she did. But a woman had to be subservient first to God, and then, to her husband. Miriam couldn’t imagine Mam being subservient to anyone.

Growing up, Miriam had never heard her parents argue. It seemed that Mam had always agreed with every decision Dat ever made, but as Miriam grew older she realized that, in reality, it was often Dat who’d listened to Mam’s advice, especially where their children were concerned. In that way, Mam was different.

Mam had been born a Mennonite and had been baptized into the Amish church before they were married. Miriam sometimes wondered if that was what made her mother so strong-willed and independent. Would another man, even a man as good-natured and as sweet as Samuel, be able to accept Mam’s free spirit? Certainly, he’d ask her to give up teaching school. Married women didn’t work outside the home.

If they married, would Samuel expect Mam to move into his house? What would happen to Dat’s farm? To the Yoder girls, including herself? And what about Irwin? His closest relatives were Norman and Lydia Beachy; he’d lived with them when he first came to Seven Poplars, but that hadn’t worked out well. That was why Irwin now lived with Miriam’s family. If Mam and Samuel were to marry, would Samuel want to send Irwin back to the Beachy farm?

Mam and Miriam and her sisters had made out fine in the two years since Dat’s death. It hadn’t been easy, but they managed. There were a lot of ways a stepfather could disrupt the Yoder household, and thinking about it made Miriam uneasy. Ruth leaving to marry Eli was enough change for one year. Wasn’t it?

“Whoa,” Anna said. “That section of the floor is already done.”

Miriam looked up. As usual, she’d been so deep in her thoughts that she’d forgotten to pay attention to what she was doing. “Oops.”

Anna laughed. “Go on. You’ve been inside too long. Find something outside to do.”

“You certain you don’t mind?” Miriam asked.

“Scrub the back porch, if you want,” Louise suggested. “It doesn’t look as though Samuel has thought of that in a while.” She pointed to the screen door. “There’s another bucket by the pump.”

“Go. Go,” Anna urged. “Any more women in here and we’ll be tripping over each other.”

Miriam went out, found a broom and proceeded to sweep the sand off the porch. She hadn’t been at it more than two minutes when Charley shouted to her from the barnyard. “Morning, Miriam.”

“Morning, Charley.”

He was raking the barnyard clean of horse droppings, and she assumed that he’d come with the other men to make the farmyard and barn ready for Sunday’s gathering. If there was work to be done, you could always count on Charley to be there.

He’d leaned his rake against the barn and started toward the porch, when Miriam heard the sound of a truck engine. As she watched, John pulled up in his truck, with Hartman Veterinary Services printed on the side.

“Who’s that?” Anna asked as she pushed open the screen door.

“John.” Miriam’s heart beat faster and she felt a little thrill of excitement. What was he doing here?

Anna snickered. “He was at our house before eight this morning. Is he going to follow you everywhere?”

John blew the horn and waved.

Miriam felt her cheeks grow hot, but she waved back.

“Who is it?” Louise stepped out on the porch behind Anna. “Oh, the vet. Samuel told me that he’d asked him to come. One of his best milkers has a swollen bag. He didn’t want it to get worse.” She glanced at Anna. “You say he was at your house this morning?”

“He’s sweet on Miriam,” Anna explained.

Miriam could hear her sister’s smile, even if she couldn’t see it. “He is not,” Miriam protested, sweeping harder. “He came to check on one of our horses. She’s developing a hoof infection. John’s watching it.”

Anna giggled. “More like he’s watching you.”

“The English vet?” Louise frowned. “Not good.” She waggled a finger. “You shouldn’t encourage him.”

“I’m not encouraging him,” Miriam said. “We’re friends, nothing more.”

“He’s not English,” Anna supplied. “He’s Mennonite.”

“Ach.” Louise shook her head. “Worse, even. You know what they say about those Mennonite boys. Wild, they are.”

“Miriam,” Mam called from inside the house. “Can you give me a hand with this?”

As she turned to make her escape into the kitchen, Miriam saw Charley walk toward John’s truck and lean in the open window. She would have given her best pair of muck boots to hear what those two were saying to each other.

Miriam’s eyelids grew heavy. When they drifted shut, Anna poked her hard in the ribs. Miriam gasped, straightened and sat upright. Then she glanced around to see if anyone else had caught her dozing off. Luckily, no one seemed to be watching her.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/emma-miller/miriam-s-heart/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Emma Miller

Miriam Yoder always thought she'd marry Charley Byler. Steady, dependable Charley, who grew up on the neighboring farm, and has been sweet on her since they were young.But then local veterinarian John Hartman catches Miriam's eye. He's handsome, charming, cares for animals–and is not Plain. While Miriam is known as the "wild" Yoder sister, she is still expected to marry a good Amish man. But what if it's God's plan to match her with John? Miriam must listen to her heart to truly know which man will claim her love and her future.

“I’m coming up,” Miriam said.

Charley offered his hand when she reached the top rung of the ladder. She took it and climbed up into the shadowy loft. Charley squeezed her fingers in his and she suddenly realized he was still holding her hand, or she was holding his; she wasn’t quite sure which it was.

She quickly tucked her hand behind her back and averted her gaze, as a small thrill of excitement passed through her.

“Miriam,” he began.

She backed toward the ladder. “I j-just wanted to see the hay,” she stammered, feeling all off-kilter. She didn’t know why, but she felt as if she needed to get away from Charley, as if she needed to catch her breath. “I’ve got things to do.”

Charley followed her down. Miriam felt her cheeks grow warm. She felt completely flustered and didn’t know why. She’d held Charley’s hand plenty of times before. What made this time different?

Charley was looking at Miriam strangely.

Something had changed between them in those few seconds up in the hayloft and Miriam wasn’t sure what.

EMMA MILLER

lives quietly in her old farmhouse in rural Delaware amid fertile fields and lush woodlands. Fortunate enough to be born into a family of strong faith, she grew up on a dairy farm, surrounded by loving parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Emma was educated in local schools, and once taught in an Amish schoolhouse much like the one at Seven Poplars. When she’s not caring for her large family, reading and writing are her favorite pastimes.

Miriam’s Heart

Emma Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Love comes from a pure heart and a

good conscience and a sincere faith.

—1 Timothy 1:5

For the lost Prince of Persia

and the blessings he has brought to our family

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Epilogue

Letter to Reader

Questions for Discussion

Chapter One

Kent County, Delaware—Early Autumn