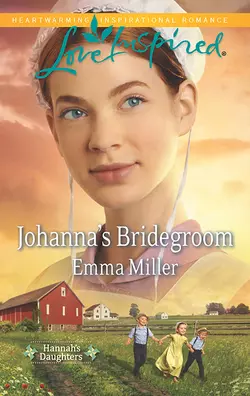

Johanna′s Bridegroom

Emma Miller

Will You Marry Me? Bold widow Johanna Yoder stuns Roland Byler when she asks him to be her husband. To Johanna, it seems very sensible that they marry. She has two children, he has a son. Why shouldn't their families become one? But the widower has never forgotten his long-ago love for her, until his foolish mistake split them apart.This could be a fresh start for both of them. Until she reveals she wants a marriage of convenience only. It's up to Roland to woo the stubborn Johanna and convince her to accept him as her groom in her home and in her heart.Hannah's Daughters: Seeking love, family and faith in Amish country.

Will You Marry Me?

Bold widow Johanna Yoder stuns Roland Byler when she asks him to be her husband. To Johanna, it seems very sensible that they marry. She has two children, and he has a son. Why shouldn’t their families become one? But the widower has never forgotten his long-ago love for her; it was his foolish mistake that split them apart. This could be a fresh start for both of them. Until she reveals she wants a marriage of convenience only. It’s up to Roland to woo the stubborn Johanna and convince her to accept him as her groom in her home and in her heart.

Silence stretched between them. Should she say something to him about what she’d been thinking?

Normally, if a girl and a boy wanted to court there was talk back and forth, between their friends at first, then the girl and boy. But she and Roland weren’t teens anymore. They didn’t really need intermediaries, did they? She looked around. No one was within hearing distance. If she was going to say something, she had to do it now, before she lost her nerve.

“Roland?”

“Ya?”

“I want to talk to you about—”

Johanna took a deep breath and clasped her hands so that Roland wouldn’t see how they were shaking. “Roland?” she began.

In his gray eyes, color swirled and deepened. “Yes, Johanna?”

She took another breath and looked right at him. “Will you marry me?”

EMMA MILLER

lives quietly in her old farmhouse in rural Delaware amid fertile fields and lush woodlands. Fortunate enough to be born into a family of strong faith, she grew up on a dairy farm, surrounded by loving parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Emma was educated in local schools, and once taught in an Amish schoolhouse much like the one at Seven Poplars. When she’s not caring for her large family, reading and writing are her favorite pastimes.

Johanna’s Bridegroom

Emma Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy,

it does not boast, it is not proud.

—1 Corinthians 13:4

Contents

Chapter One (#u8fedbff2-b945-5801-9e43-00912349babe)

Chapter Two (#u3ed48e1c-9352-5566-8251-53cc46a68940)

Chapter Three (#u6ce155aa-ac7b-54a1-8ab1-3725033a7859)

Chapter Four (#u8e7ddb03-87f6-5626-926b-88ac1d19a4cf)

Chapter Five (#u85d8abc7-d55d-5a94-adcc-844dd222688f)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Questions for Discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

Excerpt (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One

Kent County, Delaware

June

Johanna kissed her sister’s newborn and inhaled the infant’s sweet baby scent before gently placing her into the antique walnut cradle. It was midafternoon, and Johanna, Anna, Rebecca and Grossmama were gathered on the screened-in back porch of the Mast farmhouse, enjoying cold lemonade and hulling a bounty of end-of-the-season strawberries to make jam.

Johanna stood over the cradle, gazing down at the baby’s long thick lashes, her chubby, pink cheeks and the riot of red-gold curls peeping out from under her antique, white-lace bonnet. Tiny Rose sighed in her sleep, opened one perfect hand, pursed her perfectly formed lips and melted Johanna’s heart. Tears blurred her vision. She’s so precious.

It wasn’t that she coveted Anna and Samuel’s gift from God. She didn’t. But it seemed so long since her own children had been newborns. Jonah, at five, was now old enough to be a real help in the garden and barnyard. And, as he reminded her at least three times a day, he’d be starting school in the fall. Even her chatterbox, Katy, now three, had outgrown her baby smocks and become independent overnight. She was always eager to sweep the kitchen floor with her miniature broom, gather eggs and pick strawberries in the wake of the bigger children.

I want another baby, Johanna admitted to herself. My arms ache for another child, but having one means marrying again. And after her unhappy marriage to Wilmer Detweiler, and the tragedy of his suicide, she wasn’t certain she had the strength to face that yet.

She knew that the children she had, especially Jonah, needed a father. She and Jonah had always been close, but there were so many things that only a man could teach him—how to plow and trim a horse’s hooves, when to cut hay, how to mend a broken windmill. And while Wilmer had been kind to Katy, he’d shown only stern disapproval and constant criticism of Jonah. For all his energy and warm heart, Jonah desperately needed a loving father’s guidance. Without it, Johanna feared that Jonah would never fully understand how to grow into a man. And she wasn’t the only one who had come to that conclusion. It had been two years since Wilmer’s death, and members of the community and her family had been hinting that it was time she remarry. Johanna prayed every night that she would know when the time was right and that God would bring a good man into her life.

“She’s adorable, Anna.” Beautiful, she thought, but she didn’t say the word out loud. Physical beauty wasn’t something the Old Order Amish were supposed to dwell on. Better a child or an adult have grace and a pure spirit within than a pleasing face.

“And such an easy baby,” Grossmama said. “Like my Jonas. A gut baby.” She capped a large crimson strawberry and popped it in her mouth. Closing her eyes, she chewed contentedly, savoring the sweet flavor.

Anna looked up from the earthenware bowl in her lap and smiled with barely contained pride. “Rose is a good baby, isn’t she? Poor Samuel can’t believe it. He keeps getting out of bed at night to make certain she’s still breathing.”

Grossmama’s eyes snapped open, and she nodded so hard her bonnet strings bounced. “Happy mudder, happy kinner. And such a quick delivery. Pray that Martha has such an easy birth when her time comes.”

“It’s Ruth who’s expecting,” Rebecca gently reminded her grandmother. “Not Aunt Martha. Our sister Ruth.”

Johanna tried not to smile at the thought of Aunt Martha, older than her mother, having a new baby. Grossmama’s physical health had been good, and she seemed happier since coming to live with Anna, but her memory continued to fail. Not only was she convinced that Anna’s husband, Samuel, was her dead son, Jonas, but she mixed up names and people so often that one had to constantly think twice when one had a conversation with her. Only yesterday, Grossmama had been certain that Bishop Atlee was her new beau, come to take her to a frolic. Johanna couldn’t help wondering what the English at the senior center, where Grossmama taught rug making several days a week, thought of their grandmother.

“Are these the last of them?” Rebecca asked. Two brimming dishpans of ripe strawberries stood on the table, waiting to be washed and crushed before being added to the bubbling kettles on the stove.

“No,” Johanna said. “I think there’s one more flat. I’ll go—” She broke off as the pounding of a horse’s hooves on the dirt lane caught her attention. “It’s Irwin!” She snatched open the screen door and hurried down the wooden steps, wondering why he was in such a hurry.

Blackie galloped into the yard with Irwin, hatless and white-faced, clinging to his bare back. Chickens squawked and flew in all directions as the teenager yanked the gelding up so hard that the horse began to buck, and Irwin nearly tumbled off.

“What’s wrong?” Johanna cried. Irwin, the teen who Johanna’s mother had adopted, never moved faster than molasses in January. “Ruth’s not—”

“Not Ruth! It’s Roland’s J.J.”

Roland. For an instant, Johanna felt paralyzed. If Roland was in danger, she— No, she told herself, not Roland. J.J., Roland’s little boy. The moment passed and she regained her self-control. “What is it?” she demanded.

Irwin half slid, half jumped to the ground, letting the reins slip through his hands. Blackie made one more leap and blew flecks of foam from his mouth and nose. Neck and tail arched, the spirited horse trotted onto the lawn, where, after a few more antics, he began to snatch up mouthfuls of grass.

“You’ve got to come! Schnell!” Irwin steadied himself and ran toward Johanna. “Bees! A swarm! In Roland’s tree. They’re crawling all over J.J.! Roland says they could sting him to death!”

“Bees?” Johanna asked. “Roland doesn’t keep bees.” If J.J. was in danger, she had to go, but how could she go? After everything that lay between them, knowing how she felt, how could Roland ask it of her? “Are you certain they’re honeybees?”

Irwin nodded. “H...honeybees!”

Johanna grabbed him by his thin shoulders and shook him. “Calm down!” she ordered. “Has J.J. been stung?”

“Ne.” Irwin shook his head. “Roland doesn’t know what to do. He says you have to come. You know bees.”

“All right,” Johanna agreed. J.J.’s little face, the image of his father, flashed through her thoughts, and she swallowed, trying to keep her voice from showing what she really felt. “You run to our farm,” she instructed Irwin calmly. “Get my smoker and my bee suit and an empty nuc box and bring them to Roland’s.”

He knitted his eyebrows. “What kind of box?”

“A used hive body. A deep one. And don’t forget my lemongrass oil. It’s on the shelf beside my gloves. Bring them to Roland’s.” She took a deep breath and pressed her hands to her sides to keep anyone from seeing them tremble. “Can you remember all that?”

He nodded.

“Good. Now run, as quickly as you can!”

Anna and Rebecca had followed her into the yard. “What’s happened?” Rebecca asked.

“Irwin says that there’s a swarm of bees at Roland’s.”

“In the tree! By the pond. And...and J.J.’s up in the tree with them,” Irwin said. For all his fourteen years, he looked as though he was about to burst into tears. Red patches stood out on his blotchy complexion, and his hay-thatch hair stuck up in tufts. Somewhere, he’d lost his hat, and one suspender sagged.

“Go now,” Johanna told Irwin. “And don’t stop for anything!”

Irwin took off.

“I’ve got to go see what I can do,” Johanna said to Rebecca and Anna, taking care not to show how flustered she really was. She’d been an apiarist long enough to know that it was important to remain calm with bees. They seemed to be able to sense a person’s mood and the best way to calm a hive—or a swarm—was to stay calm herself. As if that’s possible, the warning voice in her head whispered, when you have to go to Roland’s house and pretend you’re only friends.

“Take one of our buggies,” Anna offered. “We’ll help you hitch—”

“Ne.” Johanna glanced from her sisters to where the horse grazed on the lawn. “There’s no time. I’ll ride Blackie.”

“Bareback?” Anna’s eyes widened. “Are you sure? Blackie’s—”

“Headstrong. Skittish. I know.” Johanna grimaced. “It isn’t as if we didn’t get thrown off worse when we were kids.” How could she tell Anna that she was afraid? Not of Blackie or of being thrown, but of Roland...of the past she’d thought she’d put behind her years ago?

“You’re going to ride astride, like a man?” Rebecca shook her head. “It’s against the Ordnung. Not fitting for women. Bishop Atlee will—”

“J.J.’s life might be in danger. The bishop will understand that this is an emergency,” Johanna answered with more confidence than she felt. Her heart raced as she bent and ripped up a handful of grass and walked slowly toward Blackie. The animal rolled his eyes and backed up a few steps, ears pricked and muscles tensed.

“Easy,” Johanna soothed. “Good boy. Just a little closer.” She inched forward and grabbed a trailing rein. “Give me a boost up,” she said to her sisters.

Rebecca shook her head. “You’re going to be in sooo much trouble.”

Ignoring Rebecca, Anna moved to Blackie’s side and cupped her hands. Johanna thrust a bare foot into the makeshift stirrup and swung up onto the horse’s back.

“Was is?” Grossmama shouted. “Baremlich!”

But Johanna had already pulled Blackie’s head around, grabbed a handful of mane and dug her heels into the animal’s sides. Blackie broke into a trot, and they galloped away.

* * *

Roland Byler’s stomach did a flip-flop as he stood by the pond and stared up at his only child. J.J. had climbed into the branches of a Granny Smith apple tree and sat with his back against the trunk and his legs swinging down on either side of a branch. He was at least eight feet off the ground, but the distance ordinarily wouldn’t have worried Roland too much. Although J.J. was only four, he was strong and agile, and climbed like a squirrel. He’d been scrambling up ladders and into trees almost since he’d learned to walk. What terrified Roland today was that his son was surrounded by thousands of honeybees.

“Please, God, protect him,” Roland murmured under his breath. And louder, to J.J., he called, “Sit still, don’t move. Don’t do anything to startle them.”

J.J. giggled. “Don’t be scared, Dat. They won’t hurt me. They like me.” Bees surrounded him, walking on his bare feet, his arms and fingers. They buzzed around his head and face and crawled in his hair. And only inches from J.J.’s head, a wriggling cluster of the winged insects, thicker than the boy’s body, swayed on a slender branch.

“Don’t make any noise,” Roland warned as J.J. began to hum the tune to an old hymn. Roland’s heart thudded against his ribs, his skin was clammy-cold and his chest felt so tight that it was hard to breathe. “Do as I say!” he ordered.

When Roland was ten, he’d had a cousin in the Kishacoquillas Valley who’d attempted to rob a honey tree and had been stung to death. Roland shuddered, trying to shut out the memory of the dead boy’s swollen and disfigured face as he lay in his coffin.

He couldn’t dwell on his poor cousin or his grieving family. The bishop who’d delivered the sermon at his funeral had assured them that the boy was safe with God. Roland knew that was what the Bible taught. This world wasn’t important. It was only a preparation for the next, but Roland’s faith wasn’t always as strong as he would like. His cousin’s parents had had six living children remaining when they lost their son. J.J. was all he had. Roland had survived the death of his wife, Pauline, and the unborn babies she’d been carrying, but if he lost this precious son, his own life would be over.

“They tickle.” J.J. giggled again. “Climb up, Dat, and see how nice they are.”

“Hush. I told you not to move.” All sorts of wild ideas surfaced in Roland’s head. Maybe he could cut down the tree and J.J. could jump free. Or he could tell J.J. to jump into his arms. He’d leap into the pond—washing the bees off them both before they could sting them. But Roland knew that was foolishness. Neither of them could move fast enough. The bees were already crawling all over J.J.

Besides, if Roland startled the swarm, they might all attack both of them. He didn’t care about himself, but his son was so small. The child could be stung hundreds of times in just a minute. Roland’s only hope was prayer and the belief that Irwin would return soon with Johanna. She was a beekeeper. She worked with bees every day. If anyone could tell him what to do to save his child, it would be Johanna.

“Dat!” J.J. waved a bee-covered hand and pointed toward the meadow that bordered the road.

Roland looked up to see the Yoders’ black horse coming fast across the pasture. But there was no gate along that fence line. Irwin would have to backtrack around by the farmyard to get to the pond. But the boy was galloping straight on toward—

Roland’s stomach pitched. That wasn’t Irwin on Blackie! The rider wore a blue dress and a white Kapp. A girl? It couldn’t be. “Johanna?” Roland backed away from the tree and ran toward the fence waving his arms. Was she blind? Couldn’t she see there was no opening? Why hadn’t she reined in the horse? Surely, she couldn’t mean to... “No!” he bellowed. “Don’t try to jump that—”

But as the words came out of his mouth, Roland saw that it was too late. Blackie soared over the three-rail fence and came thundering down, Johanna clinging stubbornly to his back. She yanked back on the reins, but the horse had the bit between his teeth and didn’t slacken his pace. When the gelding didn’t respond, she pulled hard on one rein, forcing him to circle left. He dug in his front legs, then tried to rear, but she fought him to a trot and finally to a walk. Johanna pulled up ten feet from Roland and slid down off the horse’s sweat-streaked back.

Johanna landed barefoot in the grass and straightened her Kapp as she hurried toward him. “Is J.J. all right?” she asked.

Speechless, Roland stared gape-mouthed at her. She was breathing hard but otherwise seemed no worse for her wild careen across the field. All he could think was that she had come. Johanna had come, and she’d find a way to save his son. But what he said was, “Are you crazy? You? A grown woman with two children? To ride that horse bareback like some madcap boy?”

Johanna...the woman who might have been his...who might have been J.J.’s mother if not for one stupid night of foolishness.

“Are you finished?” she asked, scolding him as if he was the one who’d just done something outrageous. Her chin went up and tiny lines of disapproval creased the corners of her beautiful eyes—eyes so piercingly blue and direct that for an instant, he didn’t see a delicate woman standing there. In a flash, he saw, instead, Johanna’s father, Jonas Yoder, as strong a man in faith and courage as Roland had ever known.

Johanna walked to the base of the tree, her gaze taking in J.J. and the writhing mass of bees above him. “Hi,” she called.

“Hi.” J.J. grinned at her, despite the two bees crawling over his chin. “Look at all the bees,” he said. “Aren’t they neat?”

“Very neat,” she answered softly. She tilted her head back. “That’s a lot of bees.”

“A hundred, at least,” J.J. agreed.

Roland stifled a groan. “There must be thousands of them,” he whispered.

Johanna smiled, ignoring Roland. “You’re a brave boy. Some people are afraid of honeybees.”

J.J. nodded. “They’re nice.”

“I think so, too.” Johanna glanced back at Roland. A bee lit on her Kapp, but she didn’t seem to notice. “Do you have a stepladder?”

“In the shed.”

“Could you go get it? Irwin should be coming anytime with my bee equipment. When he gets here, bring it to me. Keep Irwin away.” She grimaced. “He makes the bees nervous.”

“They make me nervous.” Roland looked from her to J.J. and back at her again. “Are you going to smoke them? I’ve heard that calms them.”

“It probably wouldn’t hurt.” She glanced back at the swarm. “They’ve left someone’s bee box somewhere, or a hollow tree,” she said to J.J. “Or maybe an abandoned building.”

“Why did they do that?” the boy asked.

“Probably because their queen was old or the hive got too crowded. They’re being so friendly because they don’t have honey to protect.” She shrugged. “They’re just looking for a new home.”

“Oh.”

“Were they in the tree when you climbed up there?” she asked.

J.J. nodded. “I wanted to see what they were doing.”

“He’s been singing to them,” Roland said, swallowing to try to dissolve his fear. “He just didn’t understand how dangerous it was.”

“The bees didn’t sting me,” J.J. said. “They like me.”

“Do they like it when you sing?” Johanna asked. And when J.J. nodded, she added, “Then you can sing to them, if you want to. I sing to mine all the time.”

J.J. giggled. “You do?”

“The ladder,” she reminded Roland as she continued to watch J.J. in the tree.

Roland backed away slowly. He was still sweating and his hands and feet felt wooden, but some of the awful despair that had paralyzed him earlier had ebbed away. Johanna didn’t seem alarmed. Obviously, she had a plan.

He turned and ran. “Don’t leave him.”

“Don’t worry,” she called after him. “We’re fine, aren’t we, J.J.?”

“Ya, Dat,” he heard his son say. “We’re fine.”

Pray to God you are. Roland lengthened his stride, running with every ounce of strength in his body.

Chapter Two

“Honeybees are wonderful creatures,” Johanna told J.J. He nodded, still seemingly unafraid of the dozens of insects crawling in his hair and over his body. J.J. was calm and happy, which was good. Far too many people feared bees, and she had always believed that they sensed when you were afraid. “Do you like honey on your biscuits?” she asked, trying to distract him while they waited for Roland to return with the ladder.

“My grossmama makes biscuits sometimes. And my aunt Mary. Dat doesn’t know how.” A mischievous grin spread across J.J.’s freckled face, and he blew a bee off his nose. “Dat’s biscuits are yucky. He always burns them.”

“Biscuits can be tricky if you don’t watch them carefully,” Johanna agreed. She glanced from the boy to where Blackie grazed. When Roland got back, she’d ask him to catch the horse and walk him until he cooled down. A horse that drank too much cold water when he was hot sometimes foundered.

Absentmindedly, Johanna rubbed her shoulder. It had been years since she’d ridden a horse, and tomorrow she’d feel every day of her twenty-seven years. Not that she’d admit it to Roland or anyone else, but jumping a three-rail fence bareback hadn’t been her idea. It had been Blackie’s. And by the time she realized that there was no opening in the fence and no gate, it was too late to keep the gelding from going over.

In spite of his high-spirited willfulness, Johanna was fond of Blackie. He had a sweet disposition and he never tried to bite or kick. Despite Mam’s salary from teaching school, money from the farm, and the income from Johanna’s bees, turkeys and quilts, money was always tight. If anything happened to the young driving horse, the family would find it difficult to replace him.

“Here comes Dat,” J.J. announced.

“Remember to think good thoughts,” Johanna said aloud. In her head, she repeated the thought over and over.

“J.J., did you know that a community of bees thinks all together, like they have one brain?” she asked him, in an attempt to keep her composure, as well as help him keep his. “This swarm has drones and workers and, in the middle, a queen. The others all protect her, because without the queen, there can be no colony.”

“Why did they land in this tree in a big ball?”

“They’re looking for a new home. For some reason, and we don’t know why, they couldn’t live in their old house anymore. They won’t stay here in the tree. They need to find a safe place where they can store their honey, protect the queen and safely raise baby bees.”

“Uncle Charley said that when a honeybee stings you, it dies.”

Johanna nodded. “Uncle Charley’s right. But a bee won’t sting unless it’s afraid, afraid you’ll hurt it or that you’ll harm the hive. That’s why we stay calm and think happy thoughts when we’re near the bees.”

“They like me to sing to them.”

She smiled at J.J., wondering how so much wisdom lived in that small head. “Who taught you about bees?”

The little boy’s forehead wrinkled in concentration, and Johanna’s heart skipped a beat. She’d seen that exact expression a hundred times on Roland’s face. You think you can put the past behind you, but you can’t. All this time, she’d been telling herself that she didn’t care anymore. And she’d been wrong. Her throat clenched. She’d loved Roland Byler for more than half her life, and in spite of everything he’d done to destroy that love, she was afraid that some part of her still cared.

“Nobody told me,” J.J. said solemnly. “Bees are my friends.”

Johanna nodded. “You know what I think, J.J.? I think God gave you a special gift. I think you’re a bee charmer.”

“I am?” He flashed another grin. “A bee charmer. That’s me.”

Roland halted behind Johanna with the ladder over his shoulder. “Where do you want this? I brought some old rags and matches, in case you want to try to smoke the swarm.”

“No sign of Irwin?” Johanna looked back toward the house. “He should have been here by now.”

“I saw your buggy coming up the road. He’ll be here in a few minutes.” Roland glanced up at his son. “Are you all right? No stings?”

“Ne, Dat.” J.J. grinned. “I told you. Bees never sting me.”

Roland frowned. “I don’t know what possessed you to climb up in that tree when you saw them. You should have better sense.”

“Atch, Roland,” Johanna said, as she put a proper mental distance between them. “He’s a child. He’s naturally curious. You don’t see bees swarm every day.”

“It would suit me if I never saw another one. I don’t like bees. I never have.”

“Then it’s best if you stand back from the tree,” she cautioned. “If you’re afraid, they’ll sense it. It might upset them.”

“I can’t see that bees have much sense about anything,” Roland said. “How big can their brains be?”

“They’re smart, Dat. Johanna said they pro...pro what the queen.”

“Protect,” Johanna supplied.

“Protect the queen,” J.J. repeated with a grin.

“No need to fill the boy’s head with lecherich nonsense.” Roland used the Pennsylvania Dutch word for ridiculous. “Just get him down out of there safely.”

Johanna rolled her eyes and reached for the ladder. “Let me do that. You might startle them.”

“Don’t you want to wait for your equipment?”

“I’m not going to need it,” she said, eyeing the swarm. “J.J. and I are doing just fine. Give me the ladder.”

Roland opened the wooden stepladder and set it on the ground. “It’s too heavy for you to lift,” he muttered.

Johanna bit back a quick retort. Men! She might not be as tall and sturdy as her sister Anna, but she was strong for her size. Who did he think lifted the bales of hay and fifty-pound bags of sheep- and turkey food? And who did he suppose moved her wooden beehives?

She lifted the ladder onto her shoulder and carried it slowly over to the apple tree. “Sing to the bees, J.J.,” she said. “What do they like best?”

In a high, sweet voice, the child began an old German hymn. Johanna settled the legs of the ladder into the soft grass and put her foot on the bottom rung. She joined in J.J.’s song.

“Let me steady that for you,” Roland offered.

She shook her head. “Ne. Let them get used to me.” She began to sing again as she slowly, one step at a time, climbed the ladder. When she was almost at the top, she put out her arms. “Swing your leg over the branch,” she murmured. “Slowly. Keep singing.” J.J. did just as she instructed, and she nodded encouragement. “Easy. That’s right.”

As J.J. put his arms around her neck, she blew two bees off his left cheek.

He broke off in the middle of the hymn and giggled. “They tickle.”

Instantly, the sound of the swarm’s buzzing grew louder.

Behind her, Johanna could hear Roland’s sharp intake of breath. “Come to me,” she murmured. “Slowly. Keep singing.” Another bee took flight, leaving the child’s arm to join the main swarm. She caught J.J. by the waist, and the two of them waited, unmoving, as bees crawled out of his hair and flew into the branches above them. She brushed two more bees off his right arm. “Good. Now we’ll start down. Slow and steady.”

Sweat beaded on the back of Johanna’s dress collar and trickled down her back. Step by step, the two of them inched down the ladder, and it seemed to Johanna that the tone and volume of the colony’s buzzing grew softer.

As J.J.’s bare feet touched the earth, the last bee abandoned the child’s mop of yellow-blond hair and buzzed away. “Go on,” Johanna said to the boy. “It’s safe now. Go to your dat.”

She threw Roland an I told you so look, but her knees felt weak. She hadn’t thought the boy was in real danger, but one could never be certain. And she knew that had anything bad happened to J.J., she would have felt responsible. She’d been frightened for the boy, nothing more, she told herself. And all those silly thoughts about Roland and what they’d once meant to each other could be forgotten. They could go on as they had, neighbors, members of the same church family, friends—nothing more.

A shout from the direction of the barnyard and the rattle of buggy wheels bumping over the field announced Irwin’s arrival. “If you don’t mind, Roland, I’ll set up a catch-trap on the bench there. The water is what drew the swarm here in the first place. And if I can lure them into the nuc box, I can move the whole colony back to our place.”

When he didn’t answer, she glanced at him. No wonder he hadn’t heard her. Roland’s full attention was on his child. He was still hugging J.J. so hard that the boy could hardly catch his breath.

“Unless you’d like to keep the bees,” Johanna added. “I’ve got an extra eight-frame hive that I’m not using. I could bring it over and teach you how to—”

“You take the heathen beasts and are welcome to them,” Roland replied.

“If you’re sure, I’ll be glad to have them. But it’ll take a few weeks for the colony to settle in to a new hive, before I can move them. Of course I have to lure them into it first.”

“Whatever you want, Johanna.” His dashed the back of his hand across his eyes. “Thank you. What you did was...was brave. For a woman. For anyone, I mean. You saved J.J. and I won’t forget it.”

Johanna ruffled the boy’s hair. “I think he would have been just fine,” she said. “The bees like him.”

J.J. grinned.

“But you’ll keep well away from them in the future,” Roland admonished.

“Obey your father,” Johanna said.

“But I don’t want to stay away from them,” the child said. “I want to see the queen.”

Roland gave him a stern look. “You go near them again and—”

“Mam! Mam!”

Johanna looked back to see Jonah, wearing his bee hat and protective veil netting, leaping out of their buggy. “I remembered the lemongrass oil, Mam,” he shouted. “Irwin forgot, but I remembered.”

J.J. wiggled out of his father’s grasp and stared in awe at Jonah’s white helmet. Jonah saw the younger boy and positively strutted toward the tree.

It was all Johanna could do not to laugh at the two of them. She raised a palm in warning. “Thank you for the lemongrass oil, Jonah, but you won’t need the hat. These bees have had enough excitement for one day.” She gave her son the look, and his posturing came to a quick end.

“Hi, J.J.,” Jonah said as he removed the helmet and tucked it under his arm. “Did you get stung? Where’s the swarm?”

J.J. pointed, and the two children were drawn together as if they were magnets. Immediately, J.J., younger by nearly two years, switched from English to Pennsylvania Dutch and excitedly began relating his adventure with the bees to Jonah in hushed whispers.

“Both of you stay away from the swarm,” Johanna warned as she directed Irwin and Roland to carry the wooden hive to the bench beside the water. Irwin lifted off the top and she used the scented oil liberally on the floor of the box. “Hopefully, this will draw the bees,” she explained to Roland as they all backed away. “Now we wait to see if they’ll decide to move in. We’ll know in a day or two.”

“I brought your suit and the smoker stuff,” Irwin said.

“Danke, but I don’t think I’ll need it,” Johanna answered. “I didn’t know what I’d find.” She looked around and saw that Jonah and J.J. had caught the loose horse. “You can take Blackie for me, Irwin. Jonah and I can drive the buggy home.”

She watched as the teenager used the buggy wheel to climb up on the horse’s back and slowly rode toward the barnyard.

“Can I drive the buggy home, Mam?” Jonah asked.

Johanna laughed. “Down the busy road? I don’t think so.” Jonah’s face fell. “But you can drive back to Roland’s house, if you like.” Nodding, Jonah scrambled back up into the buggy, followed closely by J.J.

“Don’t worry,” Johanna said to Roland. “They’re perfectly safe with our mare Molly.” It was easier now that the crisis had passed, easier to act as if she was just a neighbor who’d come to help...easier to be alone with Roland and act as if they had never been more than friends.

“Dat, I’m hungry,” J.J. called from the buggy seat.

Jonah nodded. “Me, too.”

“I guess you are,” Roland said to J.J. as he and Johanna walked beside the buggy that was rolling slowly toward the barnyard. “We missed dinner, didn’t we? I think we have bologna and cheese in the refrigerator. You boys go up to the house. Tie the mare to the hitching rail and you can make yourselves a sandwich.”

J.J. made a face. “We’re out of bread, Dat. Remember? The old bread got hard and you threw it to the chickens last night.”

Roland’s face flushed. “I’ll find you something.”

“How about some biscuits?” Johanna asked, walking beside Roland. “If you have flour, I could make you some.”

“Ya! Biscuits!” J.J. cried.

Roland tugged at the brim of his hat. “I wouldn’t want to put you out. You’ve already—”

“Don’t be silly, Roland. What are neighbors for? I can’t imagine how you and J.J. manage the house and the farm, plus your farrier work, just the two of you.”

“Mary helps with the cleaning sometimes. I’ll admit that I don’t keep the house the way Pauline did.”

“It won’t be the first messy kitchen I’ve ever seen. Let me bake the biscuits,” Johanna said, eager now to treat Roland as she would any neighbor in need of assistance. “And whatever else I can find to make a meal. If it makes you feel any better, Jonah and I will share it with you. It’s the least I can do for your gift of a hive of bees.”

“A gift you’re more than welcome to.” He offered her a shy smile, and the sight of it made a shiver pass down her spine. Roland Byler had always had a smile that would melt ice in a January snowstorm.

“The thought of homemade biscuits is tempting,” he said. “There’s a chicken, too, but it’s not cooked.”

She forced herself to return his smile. “You and the boys do your chores and give me a little time to tend to the meal,” she said briskly.

“Don’t say I didn’t warn you about the kitchen. I left dirty dishes from breakfast and—”

“Hush, Roland Byler. I think I can manage.” Chuckling, she left him at the barn and walked toward the house.

* * *

An hour later, the smell of frying chicken, hot biscuits, green beans cooked with bacon and new potatoes drew Roland to the house like a crow to newly sprouting corn plants. The boys followed close on his heels as he stopped to wash his hands and splash cold pump water over his face at the sink on the back porch. Straw hat in hand, Roland stepped into the kitchen and was so shocked by its transformation that he nearly backed out the door.

This couldn’t be the same kitchen he and J.J. had left only a few hours ago! Light streamed in through the windows, spilling across a still-damp and newly scrubbed floor. The round oak pedestal table that had belonged to his father’s grandmother was no longer piled high with mail, paperwork, newspapers and breakfast dishes. Instead, the wood had been shined and set for dinner. In the center stood a blue pitcher filled with flowers and by each plate a spotless white cloth napkin. Where had Johanna found the napkins? In the year since Pauline’s death, he hadn’t seen them. But it wasn’t flowers and pretty chinaware that drew him to the table.

“Biscuits!” J.J. said. “Look, Jonah! Biscuits!”

“Let me see your hands, boys,” Johanna ordered.

Jonah and J.J. extended their palms obediently, and Roland had to check himself from doing the same. Self-consciously, he pulled out a ladder-back chair and took his place at the table. Both boys hurried to their chairs.

On the table was a platter of fried chicken, another of biscuits, an ivory-colored bowl of green beans and another of peaches.

“I thought it best just to put everything on the table and let us help ourselves,” Johanna said. “It’s the way we do it at home. I found the peaches and the green beans in the cellar. I hope you don’t mind that I opened them.”

“Fine with me.” Roland’s mouth was watering and his stomach growling. Breakfast had been cold cereal and hard-boiled eggs. Last night’s supper had consisted of bologna and cheese without bread, tomato soup out of a can and slightly stale cookies to go with their milk. He hadn’t sat down to a meal like this since he’d been invited to dinner at Charley and Miriam’s house the previous week. Roland was just reaching for a biscuit when Johanna’s husky voice broke through his thoughts.

“Bow your heads for the blessing, boys. We don’t eat before grace.”

“Ne,” Roland chimed in, quick to change his reaching for a biscuit motion to folding his hands in silent prayer. Lord, God, thank You for this food, and thank You for the hands that prepared it. He opened one eye and saw that Johanna’s head was still modestly lowered. He couldn’t help noticing that the hair along her hairline was peeping out from under her Kapp and had curled into tight, damp ringlets. Seeing that and the way Johanna had tied up her bonnet strings at the nape of her neck made his throat tighten with emotion.

Refusing to consider how pretty she looked, he clamped his eyes shut and slowly repeated the Lord’s Prayer. And this time, when he opened his eyes again, the others were waiting for him. Johanna had an amused look on her face, not exactly a smile, but definitely a pleased expression.

“Now we can eat,” she said.

Roland reached for the platter of chicken and passed it to her. “You didn’t need to clean my dirty kitchen, but we appreciate it.”

“I did need to, if I was to cook a proper meal,” she replied, accepting a chicken thigh. “It’s no shame for you to leave housework undone when you have so much to do outside. I’m only sorry you haven’t asked for help from the community.”

“We manage, J.J. and I.”

“Roland Byler. You were the first to help when Silas lost the roof on his hog pen. You must have the grace to accept help as well as give it. You can’t be so stubborn.”

“You think so?” he asked, stung by her criticism. Personally, he’d always thought that she was the stubborn one. True, he had wronged her and he’d embarrassed her with his behavior back when they’d been courting. He’d tried to apologize, more than once, but she’d never really accepted it. One night of bad choices, and she’d gone off and married another.

“Dat?” J.J. giggled. “You broke your biscuit.”

Roland looked down to see that he’d unknowingly crushed the biscuit in his hand. “Like it that way,” he mumbled as he dropped it onto his plate and stabbed a bite of chicken and a piece of biscuit with his fork.

“Gut chicken,” J.J. said.

“If you don’t eat all those biscuits, you can have one with peaches on it for dessert,” Johanna told the boys. “If you aren’t full, that is.”

“We won’t be, Mam,” Jonah said. “I never get tired of your biscuits.”

And I never get tired of watching you, Roland thought as he helped himself to more chicken. But he was building a barn out of straw, wishing for what he couldn’t have, for what he’d thrown away with both hands in the foolishness of his youth.

Johanna’s kind acts of cleaning his kitchen and cooking dinner for them had been the charitable act of one neighbor to another, nothing more. And all the wishing in the world wouldn’t change that.

Chapter Three

At nine the following Saturday morning, Johanna stood in the combined kitchen-great room of the new farmhouse that her sisters Ruth and Miriam shared. Ruth and Eli had the downstairs. Miriam and Charley occupied an apartment on the second floor, but the two couples usually took their meals together and Ruth cooked. Miriam preferred outdoor work, and Ruth enjoyed the tasks of a homemaker. It was an odd arrangement for the Amish, one that Seven Poplars gossips found endlessly entertaining, but it worked for the four of them.

“Miriam?” Johanna called up the steps. “Are you ready? Charley has the horse hitched.”

Today, Mam, most of Johanna’s sisters and the small children were all off on an excursion to the Mennonite Strawberry Festival, a yearly event that everyone looked forward to. Their sister Grace, who still lived at home but attended the Mennonite Church, owned a car. She’d graciously offered to drive some of them, and Mam, Susanna, Rebecca, Katy and Aunt Jezzy had already gone ahead with her. But there were too many Yoders to fit in Grace’s automobile, so Miriam was driving a buggyful, as well. Anna loved the Strawberry Festival, but since Rose was so tiny, Anna had decided to remain at home and keep Ruth company. Ruth was in the last stage of pregnancy with twins and preferred staying close to home and out of the heat.

“I feel bad going off and leaving the two of you,” Johanna said. “We had such a good time last year.”

Ruth settled into a comfortable chair and rubbed the front of her protruding apron. “Until these two are born, I don’t have the energy to walk to the mailbox, let alone chase my nieces and nephews around the festival.”

Anna smiled and switched small Rose, hidden modestly under a receiving blanket, to her other breast. The baby settled easily into her new position and began to nurse. “Don’t worry about us,” Anna said. “You’re so sweet to take my girls. They’ve been talking about it all week.”

“No problem. And your Naomi is such a big help with Katy.” Johanna threw a longing glance at the baby. “First Leah, then you, and Ruth in a month. It will be Miriam next, I suppose.”

“Miriam next for what?” Anna’s twin sister came hurrying down the steps in a new rose-colored dress, her prayer cap askew and her apron strings dangling.

“Kapp,” Ruth reminded.

Miriam rolled her eyes, straightened her head covering and tied her apron strings with a double knot behind her waist. “Satisfied?”

“Ya.” Ruth, always the enforcer of proper behavior when out among the worldly English, nodded. “Much better.”

“And what is it I’m next for?” Miriam asked, unwilling to have her question go unanswered.

Anna chuckled again. “A boppli, of course. A baby of your own. A little wood chopper for Charley or a kitchen helper.”

Miriam shrugged. “In God’s time. We haven’t been married that long. And it took Ruth and Eli ages to get around to it.” She glanced at Johanna with a gleam of mischief in her eyes. “How do you know it will be me? Maybe it will be your turn next. Look at you. You’ve got that look on your face when you hold Rose. You can’t wait to be a mother again.”

“She’s right,” Ruth agreed. “You’ve mourned Wilmer long enough. It’s time you married again.”

“To whom?”

Miriam laughed. “You know who. I’ve heard you’ve been at his place three times this week. And cleaned his house.”

“Only the kitchen. And he was only there the first day, the day J.J. was up the tree with the bees. The other two times he was off shoeing horses. I had to go check on the new hive. The swarm moved into my nuc box, and I’m getting free bees.” Johanna knew she was babbling on when she should have held her tongue. Arguing with Miriam always made things worse.

“I see,” Miriam said. “You’re going to take care of the bees.”

“Exactly. It doesn’t have anything to do with Roland.” Johanna sighed in exasperation. The trouble with being close to her sisters was that they knew everything. Nothing in her life was private, and all of them had an opinion they were all too willing to share. And the fact that they’d touched on a subject that had kept her awake late for the past few nights made her even more uncomfortable. First, she had to make up her own mind what she wanted. Then she would share her decision. “Who told you I went over to Roland’s three times? Rebecca or Irwin?”

Ruth chuckled. “Just a little bird. But we’re serious. It’s not good for your children to be without a father. You know Roland would make a good dat. Even Mam says so. Roland owns his farm. No mortgage. And such a hard worker. He’ll be a good provider. And don’t forget he’s got a motherless son. You two should just stop turning your backs on each other and get married.”

“Before someone else snaps him up,” Miriam quipped. “At Spence’s, I saw one of those Lancaster girls giving him the once-over. At the Beachys’ cheese stall. ‘Atch, Roland,’” she mimicked in a high, singsong voice. “‘A man alone shouldn’t eat so much cheddar and bologna in one week. Is not gut for your health. What you need is a wife to cook for you.’”

Johanna flushed. It was too warm in the house. She went to the door and opened it, letting the breeze calm her unease. In the yard, Grace’s son, ’Kota, hung out the back door of Charley’s buggy, and Anna’s Mae bounced on the front seat. She couldn’t see Anna’s Lori Ann or Jonah, but she could hear Naomi telling them to settle down. “It’s not as easy to know what to do as you think,” Johanna said to her sisters. “People change.”

“You haven’t changed,” Anna put in quietly. “What you felt for Roland years ago, that was real. It’s not too late for the two of you.”

Johanna looked back at Anna. “You think I should fling myself at him?”

Ruth folded her arms over her chest with determination. “It’s plain as the nose on your face that he still cares for you. If you weren’t so stubborn, you’d see it.”

“What happened before...between you and him...it hurt you,” Anna continued. “I remember how you cried. But Roland was young then and sowing his oats. Can’t you find it in your heart to forgive him?”

Not forgive, but forget. Could I ever trust him again?

“Miriam!” Charley shouted from outside. “Come take this horse! I don’t trust these kids with this mare, and I can’t stand here all day holding her. I’ve got work to do.”

“Go. Have fun,” Ruth said. “But promise me you’ll think about what we said, Johanna.”

“Please,” Anna said. “We only want what’s best for you and your children.”

“So do I,” Johanna admitted. “So do I.”

* * *

The Mennonite school, where the festival was held, wasn’t more than five miles away. Mam and Grace and the others were there when Johanna and her crew arrived. Jonah and ’Kota were fairly bursting out of their britches when Miriam turned the buggy into the parking lot, and Anna’s girls appeared to be just as excited. A volunteer came to take the children’s modest admittance fees and stamp the back of their hands with a red strawberry. That stamp would admit them to all the games, the rides, the petting zoo featuring baby farm animals, a straw-bale mountain and maze and a book fair where each child could choose a free book.

“There’s Katy!” Jonah cried, waving to his little sister. Katy and Susanna were riding in a blue cart pulled by a huge, black-and-white Newfoundland dog. Following close behind trudged a smiling David King, his battered paper crown peeking out from under his straw hat. David was holding tight to a string. At the end of it bobbed a red strawberry balloon.

“I want a balloon!” Mae exclaimed. “Can I have a balloon?”

“If you like,” Johanna said. “But your Mam gave you each two dollars to spend. Make sure that the balloon is what you really want before you buy it.”

“I want a balloon, too,” ’Kota declared. “A blue one.”

“Strawberries aren’t blue,” Jonah said loftily.

“Uh-huh,” ’Kota replied, pointing out a girl holding a blue strawberry balloon on a string.

Johanna smiled as she helped the children out of the buggy and sent them scurrying safely across the field that served as a parking lot. Despite his olive skin and piercing dark eyes, Grace’s little boy looked as properly plain as Jonah. The two cousins, inseparable friends, were clad exactly alike in blue home-sewn shirts and trousers with snaps and ties instead of buttons, black suspenders and wide-brimmed straw hats. No one would recognize ’Kota as the thin, shy, undersized child who’d first appeared at Mam’s back door on that rainy night last fall. Another of God’s gifts. Life was full of surprises.

“Over here,” Mam called. “Why don’t you leave the girls with us? I imagine Lori Ann, Mae and Naomi would like to ride in the dog cart.”

“There’s J.J.,” Jonah shouted. “Hey, J.J.! He’s climbing the hay bales. Can we—”

“I promised Naomi we’d go to the book fair first,” Miriam said, joining them. “Grace is working there all morning. Don’t worry about the horse. Irwin’s going to see that the mare gets water and is tied up in the shed. Do you mind if we go on ahead, inside?”

Quickly, the sisters made a plan to meet at the picnic tables in two hours. Children were divided; money was handed out and Johanna followed ’Kota and Jonah to the entrance to the straw-bale maze. From the top of a straw “mountain,” J.J. waved and called to them. The area was fenced, so she didn’t have to worry about losing track of her energetic charges. Johanna found a spot on a straw bale beside several other waiting mothers and sat down. Since J.J. was here, Johanna was all too aware that Roland couldn’t be far away. She glanced around, but didn’t see him.

Her sisters’ advice about Roland echoed many of her own thoughts. Years ago, she and Roland... No, she wouldn’t think about that. So many memories—some good, some bad—clouded her judgment. She had prayed over her indecision, but if God had a plan for her, she was too dense to hear His voice. Sometimes her inner voice whispered that she didn’t need another husband, that she and the children were doing just fine. But at other times, she was assailed by the wisdom of hundreds of years of Amish women who’d lived before her.

Amish men and women were expected to marry and live together in a home centered on faith and family and community. Remaining single went against the unwritten rules of her church. Even a widow, like her mother, was supposed to remarry. Mourning too long was considered selfish. Dat and Wilmer, to put a fine point on it, had both left this earth. It was her duty and her mother’s duty to continue on here on earth, following the Ordnung and remaining faithful to the community.

Johanna knew, in her heart of hearts, that it was time she found a new husband. She didn’t need Anna or Ruth or even her mother to tell her that. Looking at it from the church’s point of view, she had to first find a man of faith, a man who would help her to raise her children to be hardworking and devoted members of the community. Second, as a mother, she should pick someone who would set a good example, and hopefully a man who could support her and her children—those she already had and those they might have together. She hadn’t needed her sisters to offer that advice, either. She was very good at making logical decisions.

If she married Roland, she honestly believed that she wouldn’t have to worry about struggling to feed and clothe her children. His farrier business was thriving. She knew that Roland, unlike Wilmer, would never raise his hand to her in anger. And she was certain that he didn’t drink alcohol or use tobacco, both substances she abhorred. Johanna shivered as she remembered the last time Wilmer had struck her. She was not a violent woman, but it had taken every ounce of her willpower not to fight back. Instead, she’d waited until he fell into a drunken sleep, gathered her babies and fled the house.

She pushed those bad memories out of her head. With Roland, she would be safe. Her children would be safe. They wouldn’t grow up under her mother’s roof without a father’s direction. And Roland, unlike Wilmer, would be a man both she and the children could respect.

Two English girls ran out of the maze together. The women beside Johanna stood and walked away with the laughing children. Johanna glanced back at the straw mountain, saw the boys and sank again into her thoughts.

Many Amish marriages were arranged ones. And many couples who came together for logical reasons, such as partnership, sharing a similar faith and pleasing their families, came to care deeply for each other. As far as she could tell, most of the English world married for romantic love and nearly half of those unions ended in divorce.

The Amish did not divorce. Had she been forced to leave Wilmer and return to her mother’s home permanently, both of them would have been in danger of being cast out of the church—shunned. Under certain circumstances, she could have remained part of the community, but they would still have been married. As long as the two of them lived, there could be no dissolving the marriage.

Marrying a man for practical reasons would be a sensible plan. If each of them kept their part of the bargain, if they showed respect and worked hard, romantic love might not be necessary. She considered whether she would find Roland attractive if they had just met, if they hadn’t played and worked and worshiped together since they were small children. How would she react if he wasn’t Roland Byler, Charley and Mary’s older brother, if she hadn’t wept a butter churn full of tears over him? What would she do if a matchmaker told Mam that a widowed farmer named Jakey Coblentz wanted to court Johanna?

The answer was as plain as the Kapp on her head. She would agree to meet this Jakey, to walk out with him, to make an honest effort to discover if they were compatible. So why, when she valued her mother’s and her sisters’ opinions, had she been so reluctant to consider Roland? To forget what had happened? She closed her eyes and pictured his features in her mind.

“Don’t go to sleep,” a familiar male voice said.

Johanna’s eyes flew open and she jumped so hard that she nearly fell off the bale of straw. Roland stood directly in front of her, holding two red snow cones. “Roland.”

He laughed and handed her one of the treats. “It’s strawberry. If I remember, you like snow cones. Any flavor but blue.” He took a bite of his own.

She searched for something to say. In desperation, she grabbed the snow cone and took a bite. Instantly, the cold went straight to her brain and she felt a sharp pain. “Ow!”

He laughed at her, sat down beside her and reached over and wiped a granule of ice off her chin. “You always did do that,” he reminded her.

“Let me pay you for this,” she stammered.

“Ne. Enjoy. I bought it for J.J.”

Johanna gasped. “I’m eating J.J.’s snow cone?”

Roland shrugged. “I’ll buy him another one. Now that ’Kota and Jonah are up there...” Roland indicated the top of the straw slide. “With him, it would just go to waste. It would be a puddle of strawberry syrup by the time he got to eat it.” He grinned. “So you’re doing me a favor. Keeping me from wasting a dollar.”

“Oh.” She still felt flustered.

“That was smart—what you did with the bees. They went into the box you put out for them.”

Bees were a safe subject. Tentatively, she took another nibble of the snow cone. It was delicious. She couldn’t remember when she’d had one last. Whoever had made it had ground real strawberries into the juice. She fixed her gaze on the ground. Roland was wearing new leather high-top shoes. Black. His trousers were clean, but wrinkled. Very wrinkled. They needed a good pressing.

“I’ve always been afraid of bees,” he said.

She licked at the flavored ice. “I know.”

“J.J. seems fascinated by them. He asks me all kinds of questions—questions I can’t answer.”

She took another bite, chewed slowly and swallowed. “I think he’s a bee charmer. They won’t hurt him. You don’t have to worry.”

“I found the biscuits you left for us on the kitchen table Thursday. And the potato soup. They were good, really good.”

“I’m glad you liked them.” A dribble of strawberry water ran down her hand onto her wrist. She passed the paper cone into her other hand and licked up the stray drop. “Messy,” she murmured.

“Good stuff is.”

Silence stretched between them. Shivers ran down her arms. Should she say something to him about what she’d been thinking? About the two of them? Normally, if a girl and a boy wanted to court, there was talk back and forth, between their friends at first, then between the girl and boy themselves. But she and Roland weren’t teens anymore. They didn’t need intermediaries, did they? She looked around. No one was within earshot. If she was going to say something, she had to do it now, before she lost her nerve.

“Roland?”

“Ya?”

“I want to talk to you about—”

“Johanna! Johanna! Did you see? King David and me! We rode in the blue cart.” Johanna’s sister Susanna appeared in front of them, laughing merrily. “No horse. A dog. A dog pulled the cart! Did you see us ride?”

David, glued to Susanna’s side, smiled and pointed at Johanna’s snow cone. “Ice cream? I like ice cream.”

David, like Susanna, had Down’s syndrome but was harder to understand. Johanna could usually follow what he was saying. He was a good-hearted boy, always smiling, and Johanna liked him.

“Ne,” Susanna said. “Not a ice cream cone. A snow cone.” She stared longingly at Johanna’s. “Can we have one?”

“I don’t like snow. To eat it,” David said.

“You’ll like it,” Susanna assured him.

“I’ll buy you snow cones.” Roland reached into his pocket.

“You have money, Susanna,” Johanna reminded her. “Mam gave you five dollars. Did you spend it all?”

Susanna shook her head.

“It’s nice of Roland to offer, but you need to buy your own. And buy David one, too.”

Rebecca joined them, with Katy in tow. Katy looked longingly at Johanna’s snow cone.

“Here,” Johanna said. “Have the rest of mine, Katy. Or get Susanna to buy you one. She and David were just headed to the snow cone booth.”

Rebecca glanced from Johanna to Roland and back. Johanna could almost see the wheels turning in her sister’s head.

“Ah,” Rebecca said. “I think we need to find snow cones for Susanna and David. Can you help me, Katy?”

Johanna’s fingertips tingled and her chest felt tight. Maybe this wasn’t the time. Maybe Susanna and David’s interruption had kept her from doing something she’d regret. “I’ll come with you,” she said.

Rebecca chuckled. “No need. You two old people sit here in the sun. I think I saw the snow cone stand by the school.”

Roland pointed. “It’s by the gym doors, but if you don’t have enough—”

Susanna waved her five-dollar bill. “I have money,” she said. “Come on, King David.” She started off and, again, David followed.

Rebecca looked back at Johanna. “Have fun, you two,” she teased. “Come on, Katy. Would you like to see the baby lambs?”

Roland watched the four of them walk away. “Smart, your sisters,” he said. “All of them.”

Johanna smiled at him. “Ya. All of them,” she agreed. “Susanna, too.”

He nodded. “I always thought so. A credit to your parents, that girl.”

Johanna took a deep breath and clasped her hands so that Roland wouldn’t see how they were shaking. “Roland?” she began.

In his gray eyes, color swirled and deepened. “Yes, Johanna?”

She took another breath and looked right at him. “Will you marry me?”

Chapter Four

Once, when he was eighteen and learning his trade as a farrier, Roland had been kicked by a stallion his uncle was shoeing. The blow had been so quick and hard that Roland was picking himself up off the ground almost before he’d realized that he’d been struck by a flying hoof. He hadn’t lost consciousness, but for what seemed like an eternity, he hadn’t been able to think straight.

Johanna’s matter-of-fact question had much the same effect. He was stunned. “What did you say?” he stammered. Around him, the laughter and happy shrieks of the children, the red balloon that had come loose from its mooring and was floating skyward, and the sweet smell of ripe strawberries faded. For a long second, Roland’s whole world narrowed to the woman sitting beside him.

Johanna rolled her eyes. “Are you listening to me? I asked if you would marry me.”

He swallowed, opened his mouth to speak and then took a big gulp of air. “Did you just ask me to marry you?” he managed.

She folded her hands gracefully over her starched black apron. “It’s the logical thing for us to do,” she answered.

He heard what she said, but his attention was fixed on the red-gold curls that had come loose from her severe bun and framed her heart-shaped face, a face so fresh and youthful that it might have belonged to a teenage girl instead of a widow and mother in her late twenties. Johanna’s skin was fair and pink, dusted with a faint trail of golden freckles over the bridge of her nose and across her cheeks. Her eyes were the exact shade of bluebells, and her mouth was... Roland swallowed again. He’d always thought that Johanna Yoder had the prettiest mouth—even when she’d been admonishing him for something he’d done wrong.

They had a long history, he and Johanna...a history that he’d hoped and prayed would become a future. In the deepest part of his heart, he’d wanted to ask her the very question that she’d just asked him. But now that she’d spoken it first, he was poleaxed.

“Do I take that as a no?” she asked, as a flush started at her slender throat and spread up over her face. “You don’t want to marry me?”

He could hear the hurt in her voice, and his stomach clenched. Johanna’s voice wasn’t high, like most young women’s. It was low, husky and rich. She had a beautiful singing voice. And when she raised that voice in hymns during Sunday worship service, the sound was so sweet it almost brought tears to his eyes.

Abruptly, she stood.

“Ne, Johanna. Don’t!” He caught her hand. “Sit. Please.”

Clearly flustered, she jerked her hand away, but not before he felt the warmth of her flesh and an invisible rush of energy that leaped between them. The shock of that touch jolted him in the same way that his skin prickled when a bolt of lightning struck nearby in a thunderstorm. He’d never understood that, and he still didn’t, but he felt it now.

“You know I want to marry you,” he said, all in a rush, before he lost his nerve. “I’ve been waiting for the right time...when I thought you were—”

“Through mourning Wilmer?” Johanna’s blue eyes clouded with deep violet. She lowered her voice and glanced around to see if anyone was staring at them.

Roland found himself doing the same. But the children were busy climbing the mountain of straw, and no one else seemed to have noticed that the ground under his feet was no longer solid and his brain had turned to mush. He returned his gaze to her. “To show decent respect for my Pauline and your—”

“Deceased husband?” She made a tiny shrug and her lips firmed into a thin line. “Wilmer was my husband and the father of my children. We took marriage vows together, and if...” She took a deep breath. “If he hadn’t passed, I would have remained his wife.” She shook her head. “I’d be speaking an untruth if I told you that there was love or respect left in my heart for him when he died—if there wasn’t the smallest part of relief when I knew he’d gone into the Lord’s care. I know it’s a sin to feel that way, but I—”

“Johanna, you don’t have to—” he began, but she cut him off with a raised palm.

“Ne, Roland. Let me finish, please. I’ll say this, and then we’ll speak of it no more. Wilmer was not a well man. His mind was troubled. But the fault in our marriage was not his alone. I’ve spent hours on my knees asking for God’s forgiveness. I should have tried harder to help him...to find help for him.”

One of Johanna’s small hands rested on the straw bale between them, and he covered it with his own and squeezed it, out of sympathy for her pain. This time, she didn’t pull away. He waited, and she went on.

“You know I was no longer living under Wilmer’s roof when he died. His sickness and his drinking of spirits made it impossible for me to remain there with my children.” Johanna raised her eyes to meet his gaze, and Roland saw the tears that her pride would not allow to fall.

A tightness gathered in Roland’s chest. “Did he... Was Wilmer...” A rising anger against the dead man threatened to make him say things he might later regret. As Johanna had said...as Bishop Atlee had said, Wilmer’s illness had robbed him of reason. He was not responsible for what he did, and it was not for any of them to judge him. But Roland had to ask. “Did he ever hit you?”

Johanna turned her face away.

It was all the answer he needed. Roland wasn’t a violent man, but he did have a temper that needed careful tending. If Wilmer had appeared in front of them now, alive and well, Roland wasn’t certain he could have refrained from giving him a sound thumping.

Johanna’s voice was a thin whisper. “It was Jonah’s safety that worried me most. When Wilmer...” A shudder passed through her tensed frame. “When he began to take out his anger on our son, I couldn’t take it any longer. I know that it’s the right of a father to discipline his children, but this was more than discipline.” She looked back, meeting Roland’s level gaze. “Wilmer got it into his head that Jonah wasn’t his son, but yours.”

“Mine?” Roland’s mouth gaped. “But we never...you never...”

Johanna sighed. “Exactly. I’ve been accused of being outspoken, too stubborn for a woman and willful—all true, to my shame. But, you, above all men, should know that I—”

“Would never break your marriage vows,” he said. “Could never do anything to compromise your honor or that of your husband.” He fought to control the anger churning in his gut. “In all the time we courted, we never did anything more than hold hands and—”

“We kissed once,” she reminded him. “At the bishop’s husking bee. When you found the red ear of corn?”

“We were what? Fifteen?”

“I was fifteen,” Johanna said. Her expression softened, and some of the regret faded from her clear blue eyes. “You were sixteen.”

“And as I remember, you nearly knocked me on my—”

“I didn’t strike you.” The corners of her mouth curled into a smile. “I just gave you a gentle nudge, to make you stop kissing me.”

“You shoved me so hard that I fell backward and landed in a pile of corncobs. Charley told on me, and I was the butt of everyone’s jokes for months.” He squeezed her hand again. “It wasn’t much of a kiss for all that fuss, but I still remember how sweet your lips tasted.”

“Don’t be fresh, Roland Byler,” she admonished, once again becoming the no-nonsense Johanna he knew and loved. “Remember you are a grown man, a father and a baptized member of the church. Talk of foolishness between teenagers isn’t seemly.”

“I suppose not,” he said grudgingly. “But I never forgot that kiss.”

She pulled her hand free and tucked it behind her back. “Enough of that. We have a decision to make, you and I. I’ve thought about it and prayed about it. I’ve listened to my sisters chatter on the subject until I’m sick of it. You are a widower with a young son, and I’m a widow with two small, fatherless children, and it’s time we both remarried. We belong to the same church, we have the same values, and you have a farm and a good job. That we should marry and join our families is the logical solution.”

Logical? He waited for her to speak of love...or at least to say how she’d always cared for him...to say that she’d never gotten over their teenage romance.

“What?” she demanded. “Haven’t I put it plainly? We both have to marry someone. And you live close by. We’re already almost family, with your brother Charley and my sister Miriam already husband and wife. You have plenty of room for my sheep and bees. I think that empty shed would be perfect for my turkey poults.”

“Turkeys? Bees?” He stood, backed away, and planted his feet solidly. “I’d hoped there’d be a better reason for us to exchange vows. What of affection, Johanna? Aren’t a husband and wife supposed to—”

Her eyes narrowed, and a thin crease marred her smooth forehead. “If you’re looking for me to speak of romance, I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed. We’re past that, Roland. We’re too old, and we’ve seen too much of life. Don’t you remember what the visiting preacher said at Barbara and Tobias’s wedding? Marriage is to establish a family and strengthen the bonds of community and church.”

Pain knifed through him. All this time, he’d been certain that Johanna felt the same way about him that he felt about her. Not that he’d ever betrayed his late wife—not in deed and not in thought. He’d kept Johanna in a quiet corner of his heart. But now he’d thought that they’d have a second chance. “It was my fault, what happened between us. What went wrong...I’ve never denied it. I know how badly I hurt you, and I’m sorry. I’ve been sorry ever since—”

“Roland. What are you talking about? We were kids when we walked out together. Neither of us had joined the church. That’s the past. I’m not clinging to it, and you can’t, either. It’s time to look to our future. What we have to do is decide if we would be good for each other. We’re both hard workers and we’re both dedicated to our children. It seems silly for me to look elsewhere for a husband when you live so close to my mother’s farm.”

“So we’re to decide on the rest of our lives because my land lies near your mother’s?” He hesitated, realizing his words were going to get him into trouble. But he couldn’t help how he felt and he wouldn’t be able to sleep tonight if he didn’t express those feelings. “I take it that you’d want to have the banns read at the next worship service. Since you’ve already made up your mind, why wait? Widows and widowers may marry when they choose. Why waste time with courting when you could be cleaning my house and your sheep could be grazing in my meadow?”

“Are you being sarcastic?”

“Answer me one question, Johanna. Do you love me?”

She averted her eyes. “I’m too old and too sensible for that. I respect you, and I think you respect me. Isn’t that enough?”

“No.” He shook his head. “No, it isn’t.” Where had this gone so wrong? He had pictured the two of them riding out together in his two-seater behind his new trotter, imagined them taking the children to the beach, going to the State Fair together this summer. He badly wanted to court Johanna properly, and she’d shattered all his hopes and dreams by her emotionless proposal. “It’s not enough for me. And it shouldn’t be enough for you.”

She pursed her lips. “Well, that’s clear enough. I’m sorry to have troubled you, Roland. It’s plain that we can’t—”

“Can’t what? Can’t find what we had and lost? Pauline was a sensible match that suited both our families. In time, when J.J. came, love came and filled our house. When I lost her, part of my heart went with her. But I won’t marry for convenience, not again. If the feelings you have for me aren’t deep and strong, you’d be better to find some other candidate, some prosperous farmer or tradesmen who would be satisfied with a sensible wife. Because...because I’m looking for more.”

Red spots flared on Johanna’s cheeks. “It’s good we had this talk. Otherwise, who knows how much time we would have wasted when we should be looking for—”

“I hope you find what you’re searching for,” Roland said. “And when you find a man willing to settle for a partnership, I hope you’re happy.”

She folded her arms over her chest. “You don’t find happiness in others. You find it in yourself and in service to family and community.”

“So you’re saying I’m selfish?”

“I didn’t mean it that way.”

“It sounds as if that’s exactly what you meant.” With a nod, he turned to search for his son and walked away. There was nothing more to say, nothing more he wanted to hear. He wanted to make Johanna his wife. He could think of no one who would be a more loving mother to J.J., but not under these circumstances...never under these circumstances.

“I’m glad we got this straightened out,” she called after him. “Because it’s clear to me that the two of us would never work out.”

Johanna’s temper was out of the box now. She was mad, but he didn’t care. Better to have her angry at him than to feel nothing at all.

* * *

Later that evening, at the forge beside his barn, Roland shaped a horseshoe on his anvil, with powerful swings of his hammer. Sparks flew, and his brother Charley chuckled.

“Just make it fit, Roland,” Charley teased. “Don’t beat it to death.”

It was after supper, but Roland hadn’t taken time to eat. He’d been hard at work since he’d left the festival. Not wanting to spoil J.J.’s day, he’d given permission for Grace to keep him with her boy, ’Kota, and bring him home in the morning. Since tomorrow wasn’t a church Sunday, it would be a leisurely day for visiting. Hannah Yoder, Johanna’s mam, had invited him to join them for supper tonight, but after the heated words he and Johanna had exchanged, her table was the last place he wanted to be.

Besides, Roland was in no mood to be a patient father this evening.

Charley had apologized for bringing his mare to be shod so late in the day. “I wouldn’t have bothered you, but I promised Miriam we’d drive over to attend services in her friend Polly’s district. You know Polly and Evan, don’t you? They moved here from Virginia last summer.”

Roland did know Evan Beachy. The newcomer had brought a roan gelding to be shod just after Christmas. Evan was a tall, quiet man with a gentle hand for his horses. Roland liked him, but he didn’t want to make small talk about the Beachys from Virginia. He wanted to get Charley’s opinion on what had gone wrong between Johanna and him.

Charley was always quick with a joke, but he and his brother were close. Under his breezy manner, Charley hid a smart, sensible mind and a caring heart. Roland had to talk to somebody, and Charley and he had shared their successes and disappointments since they were old enough to confide in each other.

“Brought you some lamb stew,” Charley said. “And some biscuits. Figured you wouldn’t bother to make your own supper. You never did have the sense to eat regular.”

“If I ate as much as you, I’d be the size of LeRoy Zook.”

Charley pulled a face. “Don’t try to deny it. You don’t eat right. What did you have for breakfast?”

“An egg-and-bologna sandwich with cheese.”

“And dinner? Did you even have dinner today?”

Roland didn’t answer. He’d had the strawberry snow cone. He’d had every intention of asking Johanna if she’d join him for the chicken-and-dumpling special that the Mennonite ladies were offering, but after their disagreement, he’d lost his appetite.

“So, no dinner and no supper. You’re a pitiful case, brother. Good thing that I remembered to bring you Ruth’s lamb stew. She made enough for half the church.”

“I appreciate the stew and biscuits, but I can do without your sass,” Roland answered.

When the shoe was shaped to suit him, Roland pressed it to the mare’s front left hoof to make certain of the fit, then heated it and hammered it into place. Last, he checked the hoof for any ragged edges and pronounced the work sound. He released the animal’s leg, patted her neck, and glanced back at his brother.

“I’ve ruined it all between Johanna and me,” he said. And then, quickly, before he regretted his confession, he told Charley what had happened earlier in the day. “She asked me to marry her,” he said when he was done with his sad tale. “And fool that I am, I refused her.” He raised his gaze to meet his brother’s. “I don’t want a partner,” he said. “I couldn’t go into a marriage with a woman who didn’t love me—not a second time. Pauline was a good woman. We never exchanged a harsh word in all the years we were married, but I was hoping for more.”

Charley removed the sprig of new clover he’d been nibbling on. “You love Johanna, and you want her to love you back.”

Roland nodded. “I do.” He swallowed, but the lump in his throat wouldn’t dissolve. He turned away, went to the old well, slid aside the heavy wooden cover and cranked up a bucket of cold water. Taking a deep breath, he dumped the bucket over his head and sweat-soaked undershirt. The icy water sluiced over him, but it didn’t wash away the hurt or the pain of the threat of losing Johanna a second time. “Was I wrong to turn her down, Charley? Am I cutting off my nose to spite my face? Maybe I would be happier having her as a wife who respects me, but doesn’t love me, instead of not having her at all.”

Charley tugged at his close-cropped beard, a beard that Preacher Reuben disapproved of and even Samuel had rolled his eyes at, a beard that some might think was too short for a married man. “You want my honest opinion? Or do you just want to whine and have someone listen?”

“You think I’ve made a terrible mistake, don’t you? Say it, if that’s what you think. I can take it.”

Charley came to the well, cranked up a second bucket of water and used an enamel dipper to take a drink. Then he poured the rest of the bucket into a pail for the mare. She dipped her velvety nose in the water and slurped noisily.

Roland wanted to shake his brother. In typical fashion, Charley was taking his good old time in applying the heat, letting Roland suffer as he waited to hear the words. Finally, when he’d nearly lost the last of his patience, Charley nodded and glanced back from the mare.

“You’re working yourself into a lather for nothing, brother. Don’t you remember what a chase Miriam gave me? ‘We’re friends, Charley,’” he mimicked. “‘You’re just like a brother.’ Do you think I wanted to be Miriam’s friend? I loved her since she was in leading strings, since we slept in the same cradle as nurslings. Miriam was the sun and moon for me. It’s not right for a Christian man to say such things, but sinner that I am, it’s how I feel about her. But you know what men say about the Yoder girls.”

Roland nodded. “They’re a handful.”