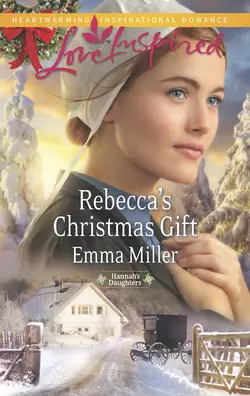

Rebecca′s Christmas Gift

Rebecca's Christmas Gift

Emma Miller

During the Christmas season, Rebecca Yoder agrees to help new preacher Caleb Wittner with this mischievous daughter. Amelia's turned the community of Seven Poplar upside down.Only Rebecca can see the pain hidden beneath the little girl's antics–and her father's brusque manner. After losing his wife in a fire, Caleb's physical scars may be healing, bu this emotions have not. Yet Rebecca's sweet manner soon has him smiling and laughing with his daughter–and his pretty housekeeper. Soon Caleb must decide whether to invite Rebecca into his life–or lose her forever.

Housekeeper For The Holidays

During the Christmas season, Rebecca Yoder agrees to help new preacher Caleb Wittner with his mischievous daughter. Amelia’s turned the community of Seven Poplars upside down. Only Rebecca can see the pain hidden beneath the little girl’s antics—and her father’s brusque manner. After losing his wife in a fire, Caleb’s physical scars may be healing, but his emotions have not. Yet Rebecca’s sweet manner soon has him smiling and laughing with his daughter—and his pretty housekeeper. Soon Caleb must decide whether to invite Rebecca into his life—or lose her forever.

Hannah’s Daughters: Seeking love, family and faith in Amish country

As Caleb entered the Yoder barn, he looked up to see Rebecca coming down the ladder from the hayloft.

She was such a pretty sight, all pink cheeked from the cold, red curls tumbling around her face, and small graceful hands—hands that could bake bread, soothe a crying child and manage a spirited driving horse without hesitation.

“Caleb!” A smile lit her eyes and spread over her face. “I didn’t expect you so early.”

“Ya.” Rebecca often made him trip over his own tongue. “You, too,” he added. “Up early.”

She nodded. “I like mornings, when it’s quiet. A barn can be almost like…like a church. The contented sounds of the animals, the rustle of hay when you throw it down from the loft and…” She broke off, laughing softly. “I must sound foolish.”

“Ne. I feel the same way…as if God is listening.”

When she looked at him, he got the feeling she saw beyond the scars on his face and hand. It was almost as if she didn’t see them at all.

EMMA MILLER

lives quietly in her old farmhouse in rural Delaware amid fertile fields and lush woodlands. Fortunate enough to be born into a family of strong faith, she grew up on a dairy farm, surrounded by loving parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Emma was educated in local schools, and once taught in an Amish schoolhouse much like the one at Seven Poplars. When she’s not caring for her large family, reading and writing are her favorite pastimes.

Rebecca’s Christmas Gift

Emma Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

“For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

—Jeremiah 29:11

Contents

Chapter One (#u67bc2feb-1517-577b-b015-eb4b60746e32)

Chapter Two (#ub66c9c04-d3c9-59dd-a5a0-a9b0561657c4)

Chapter Three (#u0f2e8e03-8b4b-5f3b-b383-f9d3a1930ec0)

Chapter Four (#ud0ac68f9-ada0-50af-b807-46c51ec3f2e4)

Chapter Five (#ub4d904a5-11aa-5991-a4b5-c57d381acc5b)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Questions for Discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

Excerpt (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One

Seven Poplars, Kent County, Delaware, Autumn

Rebecca Yoder stole another secret glance at the new preacher before ducking behind an oak tree. Today had been delightful; she couldn’t remember when she’d last enjoyed a barn raising so much. Leaning back against the sturdy trunk of the broad-leaved oak, she slipped off her black athletic shoes and wiggled her bare feet in the sweet-smelling clover. It may have been October, but fair weather often lingered late into autumn in Delaware and the earth was still warm under her feet.

She and her friends Mary Byler and Lilly Hershberger had been busy since sunup, cooking, helping to mind the children and squeezing dozens and dozens of lemons to make lemonade for the work frolic. It seemed that half the Amish in the county, and more than a few from out of state, had come to help rebuild new preacher Caleb Wittner’s barn, and everyone—from toddlers to white-haired elders—had been hungry.

As adult women, a great deal of the heavy work of feeding people fell to them. Rebecca didn’t mind—she was happy to help—and work frolics were fun. A change from everyday farm chores was always welcome, and gatherings like these gave young people from different church districts an opportunity to meet and socialize. Getting to know eligible men was the first step in courtship, as the eventual goal of every Amish girl was finding a husband.

Not that she would be in the market for one for some time. Technically, at twenty-one, she was old enough to marry, but she liked her life as it was. Her older sisters had all found wonderful husbands, and she intended to take her time and choose the right man. Good men didn’t exactly grow on trees, and she wouldn’t settle for just anyone. Marriage was for a lifetime and she didn’t want to choose in haste. If she couldn’t have someone who loved her in a romantic way, she’d remain single.

Rebecca yawned and rubbed the back of her neck. This was the first chance that she, Mary and Lilly, all of courting age, had found to take a break. Here, under the shade trees, they could take a few minutes to relax, talk and enjoy some of the delicious food they’d been serving to the men all afternoon. The fact that their chosen spot was slightly private while offering a perfect view of the young men pulling rotted siding off the old barn was a definite plus.

“I don’t care how eligible Caleb Wittner is. I wouldn’t want him.” Balancing her plate of food, Mary folded her long legs gracefully under her as she lowered herself onto the grass. Her voice dropped to a conspiratorial whisper as she leaned toward Rebecca. “Amish or not, I tell you, I wouldn’t set foot in that man’s house again, not even for double wages.”

Lilly’s curly head bobbed in agreement beneath her spotlessly starched prayer kapp. “Didn’t I tell you? I warned you before you took the job, Mary. I learned the hard way. He’s impossible to please, and that child of his...” Lilly rolled her dark eyes and raised both hands in mock horror, causing a round of mirth. Blonde, round-faced Lilly had a sweet disposition and had been a loyal pal since the three of them had gone to school together as children, but Rebecca knew she was prone to exaggeration.

Actually, Lilly and she had been first graders when they’d met. Mary had been older, but that hadn’t stopped her from taking the newcomers under her wing and helping them adjust to being away from their mothers all day. The friendship that had kindled around the school’s potbellied woodstove had only grown stronger with each passing year. And since all of them had left their school days behind and become of courting age, not a week went by without the three of them attending a young folks’ singing, a trip to Spence’s Auction or some sort of frolic together. To cement the bond even more, Mary’s brother Charley had married Rebecca’s sister Miriam, which made kinship an added blessing. So tight was hers and Mary’s friendship that Rebecca often worried how she’d stand it if she married out of the community and had to move away.

“Seriously.” Rebecca nibbled at a stuffed egg and returned to the subject of Caleb Wittner’s mischievous daughter. “She’s a four-year-old. How bad could she be?”

“Oh, she’s pretty awful.” Mary chuckled as she tucked a stray lock of fine, honey-brown hair behind her ear. “Don’t let those big, innocent eyes fool you. Turn your back on that girl and she’s stuffing a dead mouse in your apron pocket and tying knots in your shoestrings.”

“Together,” Lilly added with a grimace. “She tied my church shoes together so tight I had to cut the laces to get them apart. And while I was trying to sort them out, she dumped a crock of honey on the sermon her father had been writing.”

“I think you two are being uncharitable,” Rebecca pronounced. She eyed one of Aunt Martha’s famous pickled carrots on her plate. “And letting your imaginations run away with you.” Her attempt at reining in her friends’ criticism of Caleb and Amelia Wittner was spoiled by another giggle that she couldn’t contain. Mary was terrified of mice. Rebecca could just picture Mary’s face when she’d slipped a hand into her pocket and come up with a dead rodent.

“That’s not the half of it,” Mary went on. “Amelia’s impossible, but her father...” She pursed her lips. “He’s worse. Short-tempered. Never a kind word for me when I came to watch his daughter. Have you ever seen him smile? Even at church? It’s a wonder his face doesn’t freeze in winter. He—” Mary broke off abruptly and her face flushed. “I didn’t mean...” She shook her head. “I wasn’t mocking his scars.”

“I didn’t think you were,” Rebecca assured her. The three of them fell silent for a minute or two, and even Rebecca, who hadn’t been critical of the new preacher, felt a little guilty. Caleb had suffered a terrible burn in the fire that had killed his wife. One side of his face was perfectly acceptable, pleasant-looking even, but the other... And his left hand... She shivered. God’s mercy had saved him and little Amelia, but had left Caleb a marked man. She swallowed the lump rising in her throat. Who could blame him if he was morose and sad?

“Ya.” Lilly took a small bite of fried chicken and went on talking. “It’s true that Caleb Wittner is a grouch. And it’s not uncharitable to speak the truth about someone. He’s nothing like our old Preacher Perry. I miss him.”

“We all do.” Rebecca sipped at her lemonade, wondering if she’d made it too tart for most people. She liked it as she liked most things—with a bit of a bite. “Preacher Perry always had a joke or a funny story for everyone. What is that English expression? His cup was always full?”

Perry’s sudden heart attack and subsequent passing had been a shock to the whole community, but nothing like the surprise of having newcomer Caleb Wittner selected, within weeks of his arrival in Seven Poplars, to take his place as preacher. The position was for life, and his role as shepherd of their church would affect each and every one of them.

“You have to admit that Caleb and Amelia have certainly livened things up in the neighborhood,” Rebecca added.

The coming of the new preacher was the most exciting thing that had happened in Seven Poplars since Grace—Rebecca’s secret half sister—had appeared on their back porch in a rainstorm two years ago.

Without being obvious, she glanced back at the barn, hoping to catch another glimpse of her new neighbor. There were two men pulling a large piece of rotten sideboard down; one was Will Stutzman, easy to recognize by his purple shirt, and the other was her brother-in-law, John Hartman, Grace’s husband. Caleb Wittner was nowhere in sight. Disappointed, she finished the last few bites of her potato salad and rose to her feet. “We better get back and help clear away the desserts before someone comes looking for us.”

Her friends stood up, as well. “I wonder if there’s any of your sister Anna’s apfelstrudel left?” Lilly said. “I think I could make room for just one slice.”

* * *

More than two hours later, as the purple shadows of twilight settled over Caleb’s farmstead, Rebecca returned to the trees near the barn to retrieve her shoes. Most of the families who’d come to work and visit had already packed up and gone home. Only a few of those who lived nearby, including her sisters Miriam and Ruth, and their husbands remained. Rebecca had been ready to go when she realized that she was still barefoot; she’d had to stop and think where and when she’d removed her sneakers.

“I remember where they are now,” she said to her mother, Hannah, who was just climbing into their buggy. “You and Susanna go on home. I’ll go fetch my shoes and see you there.” Home was around the corner and across the street. She could just walk.

Mam and Susanna waved and their buggy rolled down the driveway, followed by her sisters and brothers-in-law behind them.

“You want us to wait?” Miriam called as Charley brought their wagon around to head down the driveway.

“I’m fine.” Rebecca waved. “See you tomorrow!” As the sun set, she turned to go in search of her shoes.

The barn stood some distance from Caleb’s home, which was a neat story-and-a-half 1920s-era brick house. English people had remodeled the house over the years, but had left the big post-and-beam barn to slowly fall into disrepair. Although the roof and siding had deteriorated, the frame of the barn remained sound.

It was the potential of the barn and outbuildings that had drawn Caleb to the ten-acre property, according to Rebecca’s brother-in-law Eli. Even though it was quickly getting dark, Rebecca had no problem finding her shoes. They were lying by the tree, exactly as she’d left them. She thrust her foot into the left one and was just lacing it up when she heard a pitiful meow. She glanced around. It sounded like a cat.... No, not a cat, a kitten. Rebecca held her breath and listened, trying to locate the source of the distressed animal. She hadn’t seen any cats on the property today. In fact, when she’d been serving at the first meal seating, she’d distinctly heard Caleb say that he didn’t like cats.

That had been a strike against him. Rebecca had always liked cats better than dogs. Cats were... They were independent. They didn’t give affection lightly, but once they’d decided that you were to be trusted, they could be a great source of company. And they kept a house free of mice. Rebecca had always believed cats to be smart, and there was nothing like a purring cat curled up in her lap at the end of a long day to soothe her troubles and put her in the right mind for prayer.

Meow. The plaintive cry of distress came again, louder than before. It was definitely a kitten; the sound was coming from the shadowy barn. As Rebecca stepped into her other shoe, she glanced in the direction of the house and yard, then back at the barn. Maybe the mother was out hunting and had left a nest of little ones in a safe spot. One of the kittens could have wandered away from the others and gotten lost.

Mee-oo-www.

That settled it. There was no way that she could go home and abandon the little creature without investigation. Otherwise, she’d lie awake all night worrying if it was injured or in danger. Shoes tied, she strode across the leaf-strewn ground toward the barn.

Today hadn’t been a proper barn raising because the men hadn’t built a new barn; they’d stripped the old one to a shell. Tomorrow the men would return, accompanied by a volunteer group from the local Mennonite church and other Amish men who hadn’t been able to take a Friday off. They’d nail up new exterior siding and put on a roof. The Amish women would return at noon with a hearty lunch and supper for the workers.

Rebecca looked up at the barn that loomed skeleton-like in the semidarkness. She wasn’t easily scared, but heavy shadows already lay deep in the structure’s interior, and she wished she’d thought to come back for her shoes earlier.

She stepped over a pile of fresh lumber and listened again. This time it was easy to tell that a kitten was crying, and it was coming from above her head. Only one section of the old loft floor remained; the planks were unsound and full of holes. The rest was open space all the way to the roof, two stories above, divided by beams. Tomorrow, men would tear out the rest of the old floor, toss down the rotten wood to be burned and hammer down new boards.

Meow.

Rebecca glanced dubiously at the wooden ladder leaning against the interior hall framing. Darkness had already settled over the interior of the barn. It was difficult to see more than a few feet, but she could see well enough to know that there was no solid floor above her. The sensible thing would be to leave and return in the morning. By then, the mother cat would probably have returned for her kitten and the problem would be solved. At the very least, Rebecca knew she should walk back to Caleb’s house to get a flashlight.

But what if the kitten fell? Nine lives or not, the loft was a good fourteen feet from the concrete floor. The baby couldn’t survive such trauma. And what if it got cold tonight? It was already much cooler than it had been this afternoon when the sun was shining. She didn’t know if the kitten could survive a night without its mama. What she did know was that she didn’t have the heart to abandon the kitten. Making up her mind, she started up the ladder.

* * *

Caleb tucked his sleeping daughter into bed; it was early for bedtime, but she’d had a long day. He covered her with a light blanket and placed her rag doll under her arm. He never picked it up without a lump of sadness tightening in his throat. Dinah had sewn the doll for Amelia before the child was born. It was small and soft and stuffed with quilt batting. Dinah’s skillful fingers had placed every stitch with love and skill, and Baby, with her blank face and tangled hair, was Amelia’s most cherished possession.

He paused to push a lock of dark hair off the child’s forehead. Amelia had crawled up into the rocking chair and fallen asleep when Caleb was seeing the last of his neighbors off. He hadn’t even had time to bathe her before carrying her upstairs to the small, whitewashed room across the hall from his own bedchamber. A mother would likely wake a drowsy child to wash her and put her in a clean nightgown before putting her to bed, but there was no mother.

It seemed to Caleb that a sleeping child ought to be left to sleep in peace. It was only natural that active kinner got dirty in the course of a busy day. Morning would be good enough for soap and water before breakfast.

“God keep you,” he murmured, turning away from the bed. To the dog standing in the doorway, he said, “Fritzy. Bescherm!” Obediently, the black Standard Poodle dropped to a sitting position and fixed his attention on Amelia.

Absently, Caleb’s hand rose to stroke the gnarled side of his face where only a sparse and ragged beard grew. The burned flesh that had pained him so fiercely in the days after the fire had finally healed. Now he had no feeling in the area at all.

Some said that he’d been lucky that his mouth hadn’t been twisted, that his speech remained much as it had always been, but Caleb didn’t agree. Luck would have been reaching his wife before the smoke had claimed her life. Luck would have been that Dinah and he and Amelia could have built a new home and continued their lives as before. A small voice whispered from the far corner of his consciousness that he asked too much of God, that the blessing had been that his daughter had come out of that inferno alive.

He did not blame God. The fire that had consumed their farmhouse had been an accident. A gust of wind... A spark from a lamp. The cause was never truly determined, but as Caleb saw it, the fault, if there was fault, had been his. He had not protected his family, and his precious wife had been lost to him and his beloved child.

“Watch over her,” he ordered the dog. With Fritzy on duty, Caleb was free to check that his horse was safe, that the toolshed doors were locked and that all was secure.

Flat, green Delaware was a long way from the dry highlands of Idaho and the Old Order Amish community that he’d left behind. After the fire and the death of his wife, Caleb had tried to do as his bishop had urged. He’d tried to pick up his life and carry on for the sake of his child. He’d even gone so far as to consider, after a year, courting a plump widow with a kind face who belonged to his church. But the bitter memories of his past had haunted him and he’d decided to try to pick up the pieces of his life somewhere new. In Idaho, there had been no family ties to hold him. Here, where his cousin Eli lived, things might be better. It had to be good for Amelia to grow up with relatives, and Eli’s wife had six sisters. A woman’s hand was what Amelia needed, he told himself.

Caleb left the kitchen and walked out into the yard. All was quiet. His house was far enough off the road that he wasn’t bothered by the sounds of passing traffic. There were several sheds and a decent stable for the horse. The old barn, a survivor from earlier times than the house, stood farther back. Caleb was pleased with the work that had been done on it today. Alone, it would have taken him months. There were good people here, people that he instinctively knew he could trust. He prayed to God that this move to Delaware had been the right one for both him and Amelia.

He walked on a little farther, drawn by the sweet scent of new wood that lay stacked, ready and waiting for the following day. He stood for a moment in the semidarkness and gazed up at the exposed beams. He thought about the laughter and the camaraderie during their work today. Everyone had been kind to him and Amelia, trying to make them feel welcome. And he had felt welcome...but he hadn’t felt as if he was part of the community. He still felt like an outsider, looking in through a glass-paned window, hearing their laughter but not feeling it. And he so wanted to feel laughter again.

Caleb was about to turn back to the house when he heard a thud and then a clatter from the barn. Something had fallen or been knocked over inside the building. Had some animal wandered in? Or did he have a curious intruder? “Who’s there?” he called as he approached the open front wall.

“Just me,” came a woman’s voice from high above.

Caleb stepped inside and looked up to see a shadowy form swaying on a loft floor beam. A sense of panic went through him and he raised both hands. “Stop! Don’t move!”

“I’m fine. I just—” Her foot slipped and she swayed precariously, arms outstretched, before recovering her balance.

Caleb gasped. “Stay where you are,” he ordered. “I’m coming up.”

“I’ll be fine.” She lowered herself down onto the beam until she was kneeling. “It’s just hard to see. Do you have a flashlight?”

“What in the name of common sense are you doing in my loft, woman?” He ran for the ladder and climbed it at double speed. “Ne! Don’t move.”

“I don’t need your help,” she said, taking a sassy tone with him. Rising to her feet again, she began traversing the beam toward him.

“I told you to stay put!” Caleb had never been afraid of heights, but he was all too aware of the distance to the concrete floor and the possibility of serious injury or death if one or both of them fell. He stood cautiously, finding his balance, then stepped slowly toward her.

“Go back,” she insisted. “I can do this.”

“Ya, maybe you can,” he answered gruffly. “Or maybe you can’t, and I’ll have to scrape you up off my barn floor with a shovel.” He quickly closed the distance between them, reached out and swept her up in his arms.

Chapter Two

Caleb carried Rebecca to the end of the crossbeam and set her securely on the ladder. “You got your balance?”

Her hands tightened on the rung and she found solid footing under her before answering. “I’m fine. I really could have managed the beam.” She slipped into the Pennsylvania Deitsch dialect that was their first language. “I wasn’t going to fall.” It wasn’t as if she hadn’t climbed the loft ladder in her father’s barn a thousand times without ever slipping. Nimbly, she made her way down the ladder to the barn floor and stepped aside to allow him to descend.

“It didn’t look like you were managing. You nearly fell off before I got to you.”

A sharp reply rose in Rebecca’s mind, but she pressed her lips together and swallowed it. Caleb Wittner’s coming to her rescue, or what he’d obviously believed was coming to her rescue, was almost... It was... Her lips softened into a smile. It was as romantic as a hero coming to the rescue of a maiden in a story. He’d thought she was in danger and he’d put himself in harm’s way to save her. It didn’t matter that she wasn’t really in danger. “Danke,” she murmured. “I’m sorry if I caused you trouble.”

“You should be sorry.”

His words were stern without being harsh. Caleb was obviously upset with her, but his was the voice of a take-charge and reasonable man. Somehow, even though he was scolding her, Rebecca found something pleasant and reassuring in his tone. He was almost a stranger, yet, oddly, she felt as though she could trust him.

Meow.

“Vas ist das?”

“Ach.” In the excitement of having Caleb rescue her, she’d almost forgotten her whole reason for being in the barn in the first place. “It’s a katzenbaby,” she exclaimed as she drew the little creature out of the bodice of her dress. “A kitten,” she said, switching back to English and crooning softly to it. “Shh, shh, you’re safe now.” And to Caleb she said, “It’s tiny. Probably hasn’t had its eyes open long.”

“A cat? You climbed up to the top of my barn in the dark for a katzen?”

“A baby.” She kissed the top of the kitten’s head. It was as soft as duckling down. “I think the poor little thing has lost its mother. It was crying so loudly, I just couldn’t abandon it.” She raised the kitten to her cheek and heard the crying change from a pitiful mewing to a purr. The kitten nuzzled against her and Rebecca felt the scratchy surface of a small tongue against her skin. “It must be hungry.”

“Everyone has left for the night,” he said, ignoring the kitten. “What are you still doing here?”

Rebecca sighed. “I forgot my schuhe. I’d taken off my sneakers while...” She sensed his impatience and finished her explanation in a rush of words. “I left my shoes under the tree when I went to serve the late meal. And when I came to fetch them, I heard the kitten in distress.” She cradled the little animal in her hands and it burrowed between her fingers. “Why do you think the mother cat moved the others and left this one behind?”

“There are no cats here. I’ve no use for cats,” he said gruffly. “I have no idea how this one got in my loft.”

Caleb’s English was excellent, although he did have a slightly different accent in Deitsch. She didn’t think she’d ever met anyone from Idaho. He was Eli’s cousin, but Eli had grown up in Pennsylvania.

He loomed over her. “Come to the house. My daughter is in bed, but I’ll wake her, hitch up my horse and drive you home. Where do you live?”

Rebecca felt a pang of disappointment; she’d assumed he knew who she was. She supposed that it was too dark for Caleb to make out her face now. Still, she’d hoped that he’d taken enough notice of her in church or elsewhere in the daylight to recognize her by her voice. “I’m Rebecca. Rebecca Yoder. One of Eli’s wife’s sisters.”

“Not the youngest one. What’s her name? The girl with the sweet smile. Susanna. Her, I remember. You must be the next oldest.” He took her arm and guided her carefully out of the building. “Watch your step,” he cautioned.

The moon was just rising over the trees, but she still couldn’t see his face clearly. His fingers were warm but rough against her bare skin. For the first time, she felt uncertain and a little breathless. “I’m fine,” she said, pulling away from him.

“Your mother will not be pleased that you didn’t leave with the others,” he said. “It’s not seemly for us to be alone after nightfall.”

“I’m not so young that my mother expects me to be in the house by dark.” She wanted to tell him that he should know who she was, that she was a baptized member of his church and not a silly girl, but she didn’t. “Speak in haste, repent at leisure,” her grossmama always said.

Honestly, she could understand how Caleb might have been startled to find an intruder in his barn after dark. And it was true that it was awkward, her being here after everyone else had already left. She wasn’t ready to judge him for being short with her.

“It’s kind of you to offer,” she said, using a gentler voice. “But I don’t need you to take me home. And it would be foolish to get Amelia—” she let him know that she was familiar with his daughter’s name, even if he didn’t know hers “—to wake a sleeping child to drive me less than a mile. I’m quite capable of walking home.” She hesitated. “But what do I do about the kitten? Shall I take it with me or—”

“Ya. Take the katzen. If it stays here, being so young, it will surely die.”

“But if the mother returns for it and finds it gone—”

“Rebecca, I said I haven’t seen a cat. Why someone didn’t find this kitten earlier when we were working on the loft floor, I don’t know. Now let me hitch my buggy. Eli would be—”

“I told you, I don’t need your help,” she answered firmly. “Eli would agree with me, as would my mother.” With that, she turned her back on him and strode away across the field.

“Rebecca, wait!” he called after her. “You’re being unreasonable.”

“Good night, Caleb.” She kept walking. She’d be home before Mam wound the hall clock and have the kitten warm and fed in two shakes of a lamb’s tail.

* * *

Caleb stared after the girl as she strode away. It wasn’t right that she should walk home alone in the dark. She should have listened to him. He was a man, older than she was and a preacher in her church. She should have shown him more respect.

Rebecca Yoder had made a foolish choice to fetch the kitten and risk harm. Worse, she’d caused him to make the equally foolish decision to go out on that beam after her. He clenched his teeth, pushing back annoyance and the twinge of guilt that he felt. What if the young woman came to harm between here and her house? But what could he do? He couldn’t leave Amelia alone in the house to run after Rebecca. Not only would he be an irresponsible father, but he would look foolish.

As foolish as he must have looked carrying that girl.

The memory of walking the beam with Rebecca in his arms rose in his mind and he pushed it away. He hadn’t felt the softness of a woman’s touch for a long time. Had he been unnecessarily harsh with Rebecca because somewhere, deep inside, he’d been exhilarated by the experience?

Caleb sighed. God’s ways were beyond the ability of men and women to understand. He hadn’t asked to be a leader of the church, and he certainly hadn’t wanted it.

He hadn’t been here more than a few weeks and had attended only two regular church Sundays when one of the two preachers died and a new one had to be chosen from among the adult men. The Seven Poplars church used the Old Order tradition of choosing the new preacher by lot. A Bible verse was placed in a hymnal, and the hymnal was added to a pile of hymnals. Those men deemed eligible by the congregation had to, guided by God, choose a hymnal. The man who chose the book with the scripture inside became the new preacher, a position he would hold until death or infirmity prevented him from fulfilling the responsibility. To everyone’s surprise, the lot had fallen to him, a newcomer, something that had never happened before to anyone’s knowledge. If there was any way he could have refused, he would have. But short of moving away or giving up his faith and turning Mennonite, there was no alternative. The Lord had chosen him to serve, so serve he must.

Caleb looked up at his house, barely visible in the darkness, and came to a halt. He had come to Seven Poplars in the belief that God had led him here. He believed that God had a purpose for him, as He did for all men. What that purpose was, he didn’t know, but for the first time since he’d arrived, he felt a calm fall over him. Everyone had said that, with time, the ache he felt in his heart for the loss of his wife would ease, that he would find contentment again.

As he stood there gazing toward his new house—toward his new life—it seemed to Caleb that a weight gradually lifted from his shoulders. “All over a kitten,” he murmured aloud, smiling in spite of himself. “More nerve than common sense, that girl.” He shook his head, and his wry smile became a chuckle. “If the other females in my new church are as headstrong and unpredictable as she is, heaven help me.”

* * *

The following morning, Rebecca and her sisters Miriam, Ruth and Grace walked across the pasture to their sister Anna’s house on the neighboring farm. Mam, Grace and Susanna were already there, as they had driven over in the buggy after breakfast. Also present in Anna’s sunny kitchen were Cousin Dorcas, their grandmother Lovina—who lived with Anna and her husband, Samuel—and neighbors Lydia Beachy and Fannie Byler. Fortunately, Anna’s home was large enough to provide ample space for all the women and a noisy assortment of small children, including Anna’s baby, Rose, and Ruth’s twins, the youngest children, who’d been born in midsummer.

The women were in the kitchen preparing a noonday meal for the men working on Caleb’s barn, and Rebecca had just finished quietly relaying the story of her new kitten’s rescue to her sisters.

Rebecca had spent most of the night awake, trying to feed the kitten goat’s milk from a medicine dropper with little success. But this morning, Miriam had solved the problem by tucking the orphan into the middle of a pile of nursing kittens on her back porch. The mother cat didn’t seem to mind the visitor, so Rebecca’s kitten was now sound asleep on Miriam’s porch with a full tummy.

Grace fished a plastic fork out of a cup on the table, tasted Fannie’s macaroni salad and chuckled. “I’d love to have seen that preacher carrying you and the kitten across that beam,” she teased. And then she added, “Hmm, needs salt, I think.”

“Keep your saltshaker away from my macaroni salad,” Fannie warned good-naturedly from across the room. “Roman has high blood pressure, and I’ve cut him off salt. If anyone wants it, they can add it at the table.”

Grossmama rose out of her rocker and came over to the table where bowls of food for the men were laid out. “A little salt never hurt anyone,” she grumbled. “I’ve been eating salt all my life. Roman works hard. He never got high blood pressure from salt.” She peered suspiciously at the blue crockery bowl of macaroni salad. “What are those green things in there?”

“Olives, Grossmama,” Anna explained. “Just a few for color. Would you like to taste it?” She offered her a saucer and a plastic fork. “And maybe a little of Ruth’s baked beans?”

“Just a little,” Grossmama said. “You know I never want to be a bother.”

Rebecca met Grace’s gaze and it was all the two of them could do not to smile. Grossmama, a widow, had come to live in Kent County when her health and mind had begun to fail. Never an easy woman to deal with, Grossmama still managed to voice her criticism of her daughter-in-law. Their grandmother could be critical and outspoken, but it didn’t keep any of them from feeling responsible for her or from loving her.

A mother spent a lifetime caring for others. How could any person of faith fail to care for an elderly relative? And how could they consider placing one of their own in a nursing home for strangers to care for? Rebecca intimately knew the problems of pleasing and watching over her grandmother. She and her sister Leah had spent months in Ohio with her before the family had finally convinced her to give up her home and move East. Still, it was a wonder and a blessing to Rebecca and everyone else that Grossmama—who could be so difficult—had settled easily and comfortably into life with Anna. Sweet and capable Anna, the Yoder sisters felt, had “the touch.”

Lydia carried a basket of still-warm-from-the-oven loaves of rye bread to the counter. She was a willowy middle-aged woman, the mother of fifteen children and a special friend of Mam’s. “I hope this will be enough,” she said. “I had another two loaves in the oven, but the boys made off with one and I needed another for our supper.”

“This should be fine,” Mam replied. “Rebecca, would you hand me that bread knife and the big cutting board? I’ll slice if you girls will start making sandwiches.”

Lydia picked up the conversation she, Fannie and Mam had been having earlier, a conversation Rebecca hadn’t been able to stop herself from eavesdropping on, since it had concerned Caleb Wittner.

“I don’t know what’s to be done. Mary won’t go back and neither will Lilly. I spoke to Saul’s Mary about her girl, Flo, but she’s already taken a regular job at Spence’s Market in Dover,” Fannie said. “Saul’s Mary said she imagined our new preacher would have to do his own laundry because not a single girl in the county will consider working for him now that he’s run Mary and Lilly off.”

“Well, someone has to help him out,” Fannie said. She was Eli Lapp’s aunt by marriage, and so she was almost a distant relative of Caleb. Thus, she considered herself responsible for helping her new neighbor and preacher. She’d been watching his daughter off and on since Caleb had arrived, but what with her own children and tending the customer counter in the chair shop as well as running the office there, Fannie had her hands full.

Mam arched a brow wryly as she took a fork from the cup and had a taste of one of the salads on the table. “A handful that little one is. I’d take her myself, but she’s too young for school.” Mam was the teacher at the Seven Poplars schoolhouse. “My heart goes out to a motherless child.”

“No excuse for allowing her to run wild,” Grossmama put in. “Train up a child the way they should go.” This was one of their grandmother’s good days, Rebecca decided. Other than asking where her dead son Jonas was, she’d said nothing amiss this morning. Jonas was Grossmama’s son, Mam’s husband and father to Rebecca and all her sisters. But although Dat had been dead for nearly five years, her grandmother had yet to accept it. Usually, Grossmama claimed that Dat was in the barn, milking the cows, although some days, she was certain that Anna’s husband Samuel was Jonas and this was his house and farm, not Samuel Mast’s.

“Amelia needs someone who can devote time to her,” Fannie agreed. “I wish I could do more, but I tried having her in the office and...” She shook her head. “It just didn’t work out. For either of us.”

Rebecca grabbed a fork and peered into a bowl of potato salad that had plenty of hard-boiled eggs and paprika, just the way she liked it. From what she’d heard from Mam, Amelia was a terror. Fannie had gone to call Roman to the phone and the little girl had spilled a glass of water on a pile of receipts, tried to cut up the new brochures and stapled everything in sight.

“Caleb Wittner needs our help,” Mam said, handing Rebecca a small plate. “He can hardly support himself and his child, tend to church business and cook and clean for himself.”

“You should get him a wife,” Grossmama said. “I’ll have a little of that, too.” She pointed to the coleslaw. “A preacher should have a wife.”

Lydia and Mam exchanged glances and Mam’s lips twitched. She gave her mother-in-law a spoon of the coleslaw on her plate. “We can’t just get him a wife, Lovina.”

“Either a housekeeper or a wife will do,” Fannie said. “But one way or another, this can’t wait. We have to find someone suitable.”

“But who?” Anna asked. “Who would dare after the fuss he and his girl have caused?”

“Maybe we should send Rebecca,” Grace suggested.

Rebecca paused, a forkful of Anna’s potato salad halfway to her mouth. “Me?”

Her mother looked up from the bowl she was re-covering with plastic wrap. “What did you say, Grace?”

Miriam chuckled and looked slyly at Rebecca. “Grace thinks that Rebecca should go.”

“To marry Caleb Wittner?” Grossmama demanded. “I didn’t hear any banns cried. My hearing’s not gone yet.”

Anna glanced at Rebecca. “Would you consider it, Rebecca? After...” She rolled her eyes. “You know...the kitten incident.” Anna’s round face crinkled in a grin.

Rebecca shrugged, then took a bite of potato salad. “Maybe. With only me and Susanna at home, and now that Anna has enough help, why shouldn’t I be earning money to help out?”

“You can’t marry him without banns,” Grossmama insisted, waving her plastic fork. “Maybe that’s the way they do it where he comes from. Not here, and not in Ohio. And you are wrong to marry a preacher.”

“Why?” Mam asked mildly. “Why couldn’t our Rebecca be a preacher’s wife?”

“I didn’t agree to marry him,” Rebecca protested, deciding to try a little of the pasta salad at the end of the table. “I didn’t even say I’d take the job as housekeeper. Maybe.”

“You should try it,” Anna suggested.

Rebecca looked to her sister. “You think?” She hesitated. “I suppose I could try it.”

“Gut. It’s settled, then,” Fannie pronounced, clapping her hands together.

“Narrisch,” her grandmother snapped. “Rebecca can’t be a preacher’s wife.”

“I’m not marrying him, Grossmama,” Rebecca insisted.

“You’re going to be sor-ry,” Ruth sang. “If that little mischief-maker Amelia doesn’t drive you off, you and Caleb Wittner will be butting heads within the week.”

“Maybe,” Rebecca said thoughtfully, licking her plastic fork. “And maybe not.”

Chapter Three

Two days later, Caleb awoke to a dark and rainy Monday morning. He pushed back the patchwork quilt, shivered as the damp air raised goose bumps on his bare skin and peered sleepily at the plain black clock next to his bed. “Ach!” Late... He was late, this morning of all mornings.

He scrambled out of bed and fumbled for his clothes. He had a handful of chores to do before leaving for the chair shop. He had to get Amelia up, give her a decent breakfast and make her presentable. He had animals to feed. He’d agreed to meet Roman Byler at nine, in time to meet the truck that would be delivering his power saws and other woodworking equipment. Roman and Eli had offered to help him move the equipment into the space Caleb was renting from Roman. He’d never been a man who wanted to keep anyone waiting, and he didn’t know Roman that well. Not only was Roman a respected member of the church, but he was Eli’s partner. What kind of impression would Caleb make on Roman and Eli if he was late his first day of work?

Caleb yanked open the top drawer of the oak dresser where his clean socks should have been, then remembered they’d all gone into the wash. Laundry was not one of his strong points. He remembered that darks went in with darks, but washing clothes was a woman’s job. After four years of being on his own, he still struggled with the chore.

When confronted with a row of brightly colored containers of laundry detergent in the store, all proclaiming to be the best, he always grabbed the nearest. Bleach, he’d discovered, was not his friend, and neither was the iron. He was getting good at folding clothes when he took them off the line, but he’d learned to live with wrinkles.

Socks were his immediate problem. He’d done two big loads of wash on Friday, but the clean clothes had never made it from the laundry basket in the utility room back upstairs to the bedrooms. “Amelia,” he called. “Wake up, buttercup! Time to get up!” Sockless, Caleb pulled on one boot and looked around for the other. Odd. He always left both standing side by side at the foot of his bed. Always.

He got down on his knees and looked under the bed. No boot. Where could the other one have gone?

Amelia, he had already decided, could wear her Sunday dress this morning. That, at least, was clean. Fannie had been kind enough to help with Amelia sometimes, and Caleb had hoped that he could impose on her again today. The least he could do was bring her a presentable child.

“Amelia!” He glanced down the hallway and saw, at once, that her bedroom door was closed. He always left it open—just as he always left his shoes where he could find them easily in the morning. If the door was closed, it hadn’t closed itself. “Fritzy?” No answering bark.

Caleb smelled mischief in the air. He hurried to the door, opened it and glanced into Amelia’s room. Her bed was empty—her covers thrown back carelessly. And there was no dog on watch.

“Amelia! Are you downstairs?” Caleb took the steps, two at a time.

His daughter had always been a handful. Even as a baby, she hadn’t been easy; she’d always had strong opinions about what she wanted and when she wanted it. It was almost as if an older, shrewder girl lurked behind that innocent child’s face and those big, bright eyes, eyes so much like his. But there the similarity ended, as he had been a thoughtful boy, cautious and logical. And he had never dared to throw the tantrums Amelia did when things didn’t go her way.

Caleb reached the bottom of the stairs and strode into the kitchen, where—as he’d suspected—he found Amelia, Fritzy and trouble. Amelia was helping out in the kitchen again.

“Vas ist das?” he demanded, taking in the ruins of what had been a fairly neat kitchen when he’d gone to bed last night.

“Staunen erregen!” Amelia proclaimed. “To surprise you, Dat.”

Pancakes or biscuits, Caleb wasn’t certain what his daughter had been making. Whatever it was had taken a lot of flour. And milk. And eggs. And honey. A puddle of honey on the table had run over the edge and was dripping into a pile of flour on the floor. Two broken eggs lay on the tiles beside the refrigerator.

“You don’t cook without me!”

Fritzy’s ears pricked up as he caught sight of the eggs. That’s when Caleb realized the dog had been gulping down a plate of leftover ham from Saturday’s midday meal that the neighborhood women had provided. He’d intended to make sandwiches with the ham for his lunch.

“Stay!” Caleb ordered the dog as he grabbed a dishcloth and scooped up the eggs and shells.

“I didn’t cook,” Amelia protested. “I was waiting for you to start the stove.” Her lower lip trembled. “But...but my pancakes spilled.”

They had apparently spilled all over Amelia. Her hands, face and hair were smeared with white, sticky goo.

Then Caleb spotted his boot on the floor in front of the sink...filled with water. He picked up his boot in disbelief and tipped it over the sink, watching the water go down the drain.

“For Fritzy!” she exclaimed. “He was thirsty and the bowls was dirty.”

They were dirty, all right. Every dish he owned had apparently been needed to produce the floury glue she was calling pancakes. “And where are my socken?” he demanded, certain now that Amelia’s mischief hadn’t ended with his soggy boot. He could see the wicker basket was overturned. There were towels on the floor and at least one small dress, but not a sock in sight.

“Crows,” Amelia answered. “In our corn. I chased them.”

Her muddy nightshirt and dirty bare feet showed that she’d been outside already. In the rain.

“You went outside without me?”

Amelia stared at the floor. One untidy pigtail seemed coated in a floury crust. “To chase the crows. Out of the corn.”

“But what has that to do with my socks?”

“I threw them at the crows, Dat.”

“You took my socken outside and threw them into the cornfield?”

“Ne, Dat.” She shook her head so hard that the solid cone of flour paste on her head showered flour onto her shoulders. “From upstairs. From my bedroom window. I threw the sock balls at the crows there.”

“And then you went outside?”

“Ya.” She nodded. “The sock balls didn’t scare ’em away, so Fritzy and me chased ’em with a stick.”

“What possessed you to make our clean socks into balls in the first place? And to throw them out the window?” Caleb shook his finger at her for emphasis but knew as he uttered the words what she would say.

“You did, Dat. You showed me how.”

He sighed. And so he had. Sometimes when he and Amelia were alone on a rainy or snowy day and bored, he’d roll their clean socks into balls and they’d chase each other through the house, lobbing socken at each other. But it had never occurred to him that she would throw the socks out the window. “Upstairs! To your room,” he said in his sternest father’s voice. He could go without his noonday meal today, and the mess in the kitchen could be cleaned up tonight, but the animals still had to be fed. And Amelia had to be bathed and fed and dressed before he took her with him.

Amelia burst into tears. “But...but I wanted to help.”

“Upstairs!”

And then, after the wailing girl fled up the steps, he looked around the kitchen again and realized that his worst fears had come to fruition. He was a failure as a father. He had waited too long to take another wife. This small female was too much for him to manage without a helpmate.

“Lord, help me,” he murmured, carrying a couple of dirty utensils to the sink. “What do I do?”

He was at his wit’s end. Although he loved Amelia dearly, he didn’t think he was an overly indulgent parent. He tried to treat his daughter as he saw other fathers and mothers treat their children. He was anxious for her to be happy here in their new home, but it was his duty to teach her proper behavior and respect for adults. Among the Amish, a willful and disobedient child was proof of a neglectful father. It was the way he’d been taught and the way his parents had raised him.

The trouble was that Amelia didn’t see things that way. She wasn’t a sulky child, and her mind was sharp. Sometimes Caleb thought that she was far too clever to be four, almost five years of age. She could be affectionate toward him, but she seemed to take pleasure in doing exactly the opposite of what she was asked to do.

With a groan, Caleb raked his fingers through his hair. What was he going to do about Amelia? So far, his attempts at finding suitable childcare had fallen short. He’d hired two different girls, and both had walked out on him in less than three weeks’ time.

Back in Idaho, his neighbor, widow Bea Mullet, had cared for Amelia when Caleb needed babysitting. She had come three days a week to clean the house, cook and tend to Amelia. But Bea was in her late seventies, not as spry as she had once been and her vision was poor. The truth was, Amelia had mostly run wild when he wasn’t home to see to her himself. Once the bishop’s wife had even spoken to him about the untidy condition of Amelia’s hair and prayer bonnet, and another time the deacon had complained about the child giggling during service. He had felt that that criticism was unfair. Males and females sat on opposite sides of the room during worship and children, naturally, were under the watchful eyes of the women. How was he supposed to discipline his daughter from across the room without interrupting the sermon?

Amelia was young and spirited. She had no mother to teach her how she should behave. Those were the excuses he’d made for her, but this morning, the truth was all too evident. Amelia was out of control. So exasperated was he, that—had he been a father who believed in physical punishment—Amelia would have been soundly spanked. But he lacked the stomach to do it. No matter what, he could never strike a child.

Caleb shook his head. He’d ignored the good advice that friends and fellow church members had offered. He’d come to Delaware to put the past behind him, but he’d brought his own stubborn willfulness with him. He’d allowed a four-year-old child to run wild. And this disaster was the result.

“Good morning,” came a cheerful female voice, startling Caleb.

He looked up and stared at the young woman standing just inside his kitchen. She’d come through the utility room.

“The door was open.” She whipped off a navy blue wool scarf and he caught a glimpse of red-gold hair beneath her kapp. Sparkling drops of water glistened on her face.

Caleb opened his mouth to reply, but she was too quick for him.

“I’m Rebecca. Rebecca Yoder. We met on your barn beam the other night.”

She offered a quick smile as she shed a dark rain slicker. Beneath it, she wore a lavender dress, a white apron and black rubber boots—two boots. Unlike him. Suddenly, Caleb was conscious of how foolish he must look, standing there with one bare foot, his hair uncombed and sticking up like a rooster’s comb and his shirt-tails hanging out of his trousers.

“My door was open?” he repeated, woodenly.

Fritzy, the traitor, wagged his stump of a tail so hard that his whole backside wiggled back and forth. He sat where Caleb had commanded him to stay, but it was clear that given the choice he would have rushed up to give the visitor a hearty welcome kiss.

“Ya. I’m guessing you weren’t the one who left it open.” She pulled off first one rubber boot and then the other and hung the rain-streaked slicker on an iron hook. “I’m here to help with the housework. And Amelia.”

She looked at him and then slowly scanned the room, taking in the spilled flour, the cluttered table and the floor. Her freckled nose wrinkled, and he was struck by how young and fetching she appeared. “Eli told you that I was coming, didn’t he?”

Eli? Caleb’s mind went blank. “N...ne. He didn’t.”

“Yesterday. He was supposed to tell you that I...” She shrugged. “Fannie sent me. Fannie Byler. She said you needed someone to...”

He couldn’t remember Eli or anyone mentioning sending another girl. Certainly not the Yoder girl. “They sent you?”

Rebecca’s small fists rested on her shapely hips. “You’re not still angry about Friday night?” Her smile became a chuckle.

“I’m not angry,” he protested. “But you’re...you’re too...too...” He was going to say young, but he knew she was at least twenty-one. Maybe twenty-two. Old enough to have her own child. “Inexperienced. Amelia is... Can be...difficult. She—” What he was trying to say was lost in the sound of Fritzy gagging. He groaned out loud. The ham Amelia had given him was far too rich for the dog’s stomach. “Outside!” Caleb yelled. “If you’re going to be sick, do it outside!” He pushed past Rebecca and dashed through the small utility room to throw open the back door.

Not quite in time.

Fritzy made it out of the kitchen but lost it on the cement floor in front of the washing machine. “Out!” Caleb repeated. Sheepishly, the dog bounded out into the yard, where he proceeded to run in circles and snap at the raindrops. Now that his stomach had yielded up the large plate of ham, Fritzy was obviously cured.

Caleb returned to the kitchen to deal with Rebecca Yoder. “You have to go,” he said.

“Ne,” she replied, smiling again. “You have to go. Roman and Eli will be waiting for you. There’s a big truck there already. Eli said yesterday they were expecting your saws this morning.”

“I don’t need your help.”

“You don’t?” She slowly scanned the kitchen. “It looks to me as if that’s exactly what you do need.” She tapped her lips with a slender finger. “I know what the other girls said, about why they quit. I know what they said about Amelia and about you.”

“About me?” The trouble was with his daughter. What fault could those young women have found in his behavior? He hadn’t done or said anything—

“They said you are abrupt and hard to please.” She sounded...amused.

“I am not!”

“Dat!”

Caleb turned toward the sound of Amelia’s voice. She was standing in the kitchen doorway, still in her wet and muddy nightgown, her face streaked with tears. In one hand she held a pair of scissors, and in the other, a large section of her long, dark hair.

“Amelia?” He grabbed the scissors. “What have you done?”

“I’ll tend to her,” Rebecca assured him without the least bit of concern in her voice. She walked calmly over to Amelia, as if little girls cut their hair every day. “This is women’s work. Isn’t it, Amelia?” She looked down at the little girl.

Amelia looked up at her, obviously unsure what to think.

Caleb hesitated. He couldn’t just walk out and leave his daughter with this girl, could he? What if that only made things worse?

“I’ll be here just as a trial,” Rebecca said. “A week. If we don’t suit, then you can find someone else.”

Caleb didn’t know what to say. He really didn’t have a choice, did he? The men would be waiting for him. “A week? Ya.” He nodded, on firmer ground again. He wouldn’t be that far away. It might be easier to let this young woman try and fail than to argue with her. “Just a week,” he repeated. He looked at Amelia. “Dat has to go to work,” he said. “This... Rebecca will look after you...and help you tidy up your breakfast.” He looked around the kitchen and shuddered inwardly. “I hope you are made of sterner stuff than the past two girls,” he said to Rebecca.

“We’ll see,” Rebecca answered as she gathered the still-weeping child in her arms. “Breakfast and clean clothing for Amelia...and two boots for you are a start, wouldn’t you agree?”

* * *

The strenuous task of unloading the heavy saws and woodworking equipment took all of Caleb’s concentration for three hours. But when the truck pulled away and he was left alone to organize the tools in his area partitioned off in Roman’s shop, his thoughts returned to Rebecca and his daughter. What if he’d been so eager to get out of the house and to his tools that he’d left Amelia with someone unsuited to the task? What if Amelia disliked Rebecca or was fearful of her? What if Amelia had been so bad that Rebecca had walked out and left the child alone?

Once doubt had crept into his mind, Caleb began to worry in earnest. The thing to do, he decided as he slid a chisel into place on a rack, would be to walk back home and check on them. It wasn’t unreasonable that a father make certain that his new housekeeper was doing her job and watching over Amelia. It was still spitting rain, but what of it? And there was the matter of the blister on his heel, where his shoe had rubbed against his bare foot for the past few hours. Putting a Band-Aid on the blister made sense. He couldn’t afford to be laid up with an infection, not with the important contract to fulfill in the next thirty-eight days.

Caleb surveyed his new workbench and tables. This was a larger space than he’d had on his farm back in Idaho. Once everything was in place—drills, fretsaw, coping saws, hammers, mallets, sanders, planes, patterns and the big, gas-powered machinery—he could start work. Many of his tools were old, some handed down from his great-grandfather. The men in his family had always been craftsmen and had earned their living as cabinetmakers and builders of fine furniture. Only a few of his family’s personal antiques had survived the fire: a walnut Dutch cupboard carved with the date 1704, a small cherry spice cabinet, and an aus schteier kischt, a blanket chest painted with unicorns, hearts and flowers that would one day be part of Amelia’s bridal dowry.

A tickle at the back of Caleb’s throat made him swallow. He didn’t want to think of Amelia growing up and leaving him to be a wife. He knew it must be, but she was all he had and he wanted to keep her close by him for a long, long time. Impatient with his foolishness—worrying about her marriage when she had yet to learn her letters and still slept with her thumb in her mouth—he pushed away thoughts of Amelia as an adult. What should concern him was her safety right now. He’d abandoned her to the care of a girl barely out of her teens. For all he knew his daughter might be neglected. She could be sliding down the wet roof or swimming in the horse trough.

Slamming the pack of fine sandpaper down on the workbench, he turned and strode toward the door that led outside to the parking lot. He swung it open and nearly collided with Rebecca Yoder, who was just coming in. In her hands, she carried a Thermos, and just behind her was Amelia with his black lunchbox. They were both wearing rain slickers and boots. Caleb had no idea how they had found Amelia’s rain slicker. It had been missing for days.

Caleb sputtered his apologies and stepped out of their way. He could feel his face flaming, and once again, he couldn’t think of anything sensible to say to Rebecca. “I...I was on my way home,” he managed. “To see about Amelia.”

His daughter giggled. “I’m here, Dat. We brought your lunch.” She held up the big black lunchbox.

“And hot cider.” Rebecca raised the Thermos. “It’s such a raw day, Amelia thought you’d like something hot.”

“Not coffee,” Amelia said. “I hate coffee. But...but I like cider.”

“There’s a table with benches in the next room,” Rebecca suggested. “Eli and Roman eat lunch there when they don’t go home. I know Eli’s there.” She pointed toward a louvered door on the far side of the room.

“I helped cook your lunch,” his daughter proclaimed proudly. “I cooked the eggs. All by myself!”

“She did,” Rebecca agreed. “And she filled a jar with coleslaw. There’s some chicken corn soup and biscuits we made. But Amelia said you liked hard-boiled eggs.”

“With salt and pepper.” Amelia bounced up and down so hard that the lunchbox fell out of her hands.

Caleb stooped to pick it up.

“Ooh!” Amelia cried.

“It’s all right,” he assured her. “Nothing broken.” He followed Rebecca and a chattering Amelia into the lunchroom. He didn’t know what else to do. And as he did, he noticed that under her raincoat, Amelia looked surprisingly neat. Her face was so clean it was shiny and her hair was plaited into two tiny braids that peeked out from under an ironed kapp. Even the hem of her blue dress that showed under her slicker was pressed.

“What...what did you two do this morning?” he asked Amelia.

“We cleaned, Dat. And cooked. And I helped.” She nodded. “I did.”

No tears, no whining, no fussing. Amelia looked perfectly content.... More than content. He realized that she looked happy. He should have been pleased—he was pleased—but there was something unsettling about this young Yoder woman.

Rebecca stopped and glanced back over her shoulder at him. Her face was smooth and expressionless, but a dimple and the sparkle in her blue eyes made him suspect that she was finding this amusing. “Do you approve?”

“Wait until I see what my kitchen looks like,” he answered gruffly.

Amelia giggled. “I told you, Dat. We cleaned.”

Rebecca’s right eyebrow raised and her lips quivered with suppressed laughter. “A week’s trial,” she reminded him. “That’s all I agreed to. By then I should know if I want to work for you.”

Chapter Four

On Friday, Caleb left work a half hour early and started home. He’d finished the ornate Victorian oak bracket that he’d been fashioning all afternoon, and he didn’t want to begin a new piece so late in the day. Three years ago, he’d switched from building custom kitchen cabinets to the handcrafted corbels, finials and other architectural items that he sold to a restoration supply company in Boise. Englishers who fixed up old houses all over the country spent an exorbitant amount of money to replicate original wooden details. Not that Caleb wasn’t glad for the business, but he guessed his thrifty Swiss ancestors would be shocked at the expense of fancy things when plain would do.

He rarely left his workbench before five, but he was still uneasy leaving Amelia with the Yoder girl. Better to arrive early and check up on them. So far, Rebecca Yoder seemed capable, and he had to admit that his daughter liked her, but time would tell. Amelia sometimes went days without getting into real mischief. And then, it was Gertie, bar the door—meaning that his sweet little girl could stir up some real trouble.

The walk home from the shop took only a few minutes, but his new workshop was far enough from his house to be respectable. Otherwise, it wouldn’t have been fitting for him to have an unmarried girl housekeeping and watching his daughter for him. He left in the morning when Rebecca arrived and she went home in the late afternoon when he returned from work. The schedule was working out nicely, and as much as he hated to admit it, it was nice to know that someone would be there in the house when he arrived home. A house could get lonely with just a man and his little girl.

When Caleb arrived home, Rebecca’s pony was pastured beside his driving horse, and the two-wheeled, open buggy that she’d ridden in this morning was waiting by the shed. A basket of green cooking apples, three small pumpkins and a woman’s sewing box filled the storage space at the rear of the buggy. As he crossed the yard toward the house, Caleb noticed that one of the kitchen windows stood open. Wonderful smells drifted out, becoming stronger as he let himself in through the back door into an enclosed porch that served as a laundry and utility room.

Fritzy greeted him, stump of a tail wagging, and Caleb paused to scratch the dog behind his ears. “I’m home,” he called. And then, to Fritzy, he murmured in Deitsch, “Good boy, good old Fritzy.”

Amelia’s delighted squeal rang out, and Caleb grinned, pleased that she was so happy to see him. But when he stepped into the kitchen, he discovered that his daughter’s attention was riveted on an aluminum colander hanging on the back of a chair.

“Again!” Amelia cried. “Let me try again!”

“Ne,” Rebecca said. “My turn now. You have to wait until it’s your turn.”

“One!” Amelia yelled.

Caleb watched, bewildered, as an object flew through the air to land in the colander.

“Two!” Into the colander.

“Three!”

A third one bounced off the back of the chair and slid across the floor to rest at his feet.

“You missed!” Amelia crowed. “My turn!”

“Vas ist das?” Caleb demanded, picking up what appeared to be a patchwork orange beanbag. “What’s going on?”

“Dat!” Amelia whirled around, flung herself across the room and leaped into his arms. “We’re playing a throwing game,” she exclaimed, somehow extracting the cloth beanbag from his hand and nearly whacking him in the eye with it as she climbed up to lock her arms around his neck. “At Fifer’s Orchard they had games and a straw maid and—”

“A maze,” Rebecca corrected. “A straw bale maze.”

“And a train,” Amelia shouted. “A little one. For kinder to ride on. And a pumpkin patch. You get on a wagon and a tractor pulls you—”

Caleb’s brow creased in a frown. “A train? You let Amelia ride on a toy train like the Englisher children?” His gaze fell on a large orange lollipop propped on the table. The candy was shaped like a pumpkin on a stick, wrapped in clear paper and tied with a ribbon. “And you bought her English sweets?” Caleb extricated himself from Amelia’s stranglehold, unwound her arms and lowered her gently to the floor. “Do you think that was wise?” he asked, picking up the lollipop and turning it over to frown at the jack-o’-lantern face painted on the back. “These things are not for Amish children.”

“Ya, so I explained to her and I’d explain to you if you’d let me speak,” Rebecca said, a saucy tone to her voice. “We weren’t the only Amish there. And it was Bishop Atlee’s wife who bought the lollipop for her. I could hardly take it back and offend the woman. I told Amelia that she couldn’t have it unless you approved, and then only after her supper. I didn’t allow her to go into the Fall Festival area with the straw maze, the rides and the face painting. I told her that those things were fancy, not plain.”

“But...” he began.

Rebecca went on talking. “Amelia didn’t fuss when I told her no, and she helped me pick a basket of apples.” Rebecca flashed him a smile. “Three of those apples are baking with brown sugar in the oven. For after your evening meal or tomorrow’s breakfast.”

Caleb ran a finger under his collar. He could feel heat creeping up his throat and his cheeks were suddenly warm. Once again this red-haired Yoder girl was making him feel foolish in his own house. “So she didn’t ride the toy train?”

“A wagon, Dat.” Amelia tossed the orange beanbag into the air. “Rebecca said that we could...to pick pumpkins and apples.”

“To find the best ones,” Rebecca explained. “We had to go to the field, so we rode the tractor wagon. Otherwise we couldn’t have carried it all back.”

“Too heavy!” Amelia exclaimed, catching hold of his hand and tugging him toward the stove. “And we made a stew—in a pumpkin! For supper!” Amelia bounced and twirled, coming perilously near the stove. He caught her around the waist and scooped her up out of danger as she chattered on without a pause for breath. “I helped, Dat. Rebecca let me help.”

Caleb exhaled, definitely feeling outnumbered and outmatched. The good smells, he realized, were coming from the oven. A cast-iron skillet of golden-brown biscuits rested on the stovetop beside a saucepan of what could only be fresh applesauce. “Maybe I was too hasty,” he managed. “But the beanbags? The money I left in the sugar bowl was for groceries, not toys. The move from Idaho was expensive. I can’t afford to buy—”

“I stitched up the beanbags at home last night.”

Rebecca’s expression was innocent, but she couldn’t hide the light of amusement in her vivid blue eyes.

“From scraps,” she continued. “And I stuffed them with horse corn. So they aren’t really beanbags.”

“Corn bags!” Amelia giggled. “You have to play, Dat. It’s fun. You count, and you try to throw the bags into the coal-ander.”

“Colander.” Rebecca returned her attention to Caleb. “It’s educational. To teach the little ones to count in English. Mam has the same game at the school. The children love it.”

Caleb’s mouth tightened, and he grunted a reluctant assent. “If the toy is made and not bought, I suppose—”

“You try, Dat,” Amelia urged. “Rebecca can do it. It’s really hard to get them in the coal...colander.” She pushed an orange bag into his hand. “And you have to count,” she added in Deitsch. “In English!”

“I don’t have time to play with you now,” Caleb hedged. “The rabbits need—”

“We fed the bunnies,” Amelia said. “And gave them water.”

“And fresh straw,” Rebecca added. She moved to the stove and poured a mug of coffee. “But maybe you’re tired after such a long day at the shop.” She raised a russet eyebrow. “Sugar and cream?”

Caleb shook his head. “Black.”

“My father always liked his coffee black, too,” Rebecca murmured, “but I like mine with sugar and cream.” She held out the coffee. “I just made it fresh.”

“Please, Dat,” Amelia begged, tugging on his arm. “Just one game.”

His gaze met his daughter’s, and his resolve to have none of this silliness melted. Such a little thing to bring a smile to her face, he rationalized...and he had been away from her all day. “Three throws,” he agreed, “but then—”

“Yay!” Amelia cried. “Dat’s going to try.”

“You have to stand back by the window,” Rebecca instructed. “Underhand works better.”

With a sigh, Caleb took to the starting point and tossed all three beanbags into the colander on the first try, one after another.

“Gut, Dat!” Amelia hopped from one foot to the other, wriggling with joy. “But you forgot to count. Now my turn. You take turns.” She gathered up the beanbags and moved back about three feet. “One...zwei...three!” She burst into giggles as she successfully got one of the three into the target.

“A tie,” Rebecca proclaimed, and when he looked at her in surprise, she said, “Amelia gets a handicap.” She shrugged and gave a wry smile. “Both on the English and on her aim.” Rebecca stepped to a spot near the utility room door, a little farther from the colander than he stood, and lobbed all of the bags in. She didn’t forget to count in English.

“Rebecca wins!” Amelia declared. “She beat you, Dat. You forgot to count.”

Caleb grimaced. “I did, didn’t I?”

Rebecca nodded. “You did.”

“The lamb’s tail,” Amelia supplied and giggled again.

“Comes last,” Rebecca finished for her.

He chuckled and took a sip of his coffee. It was good and strong, the way he liked it. But there was something extra. He sniffed the mug. Had Rebecca added something? “Vanilla?” he asked.

“Just a smidgen,” Rebecca admitted. “My father liked his that way.”

Caleb nodded and took another sip. “Not bad,” he pronounced, and then said, “Since I’m new at this corn-bag tossing, I think I deserve a rematch.”

“The champion sits out,” Rebecca explained merrily. “So you have to play Amelia.”

Caleb groaned. “Why do I think that there’s no way I can win this?”

“I go first,” Amelia said, scooping up the bag. “Eins.” She tossed the first.

“One,” Caleb corrected. “You have to say it in English, remember?”

“Two! Drei!” she squealed, throwing the third.

“Three,” he said. “One, two, three.”

“I got them all in,” Amelia said. “All drei.”

“She did,” Rebecca said. “All three in. That will be hard to beat, Caleb.”

He pretended to be worried, making a show of staring at the colander and pacing off the distance backward. Amelia giggled. “Shh,” he said. “I’m concentrating here.” When he got back to his spot by the window, he spun around, turning his back to them and tossed the first beanbag over his shoulder. It fell short, and Amelia clapped her hands and laughed.

“You forgot to count again,” she reminded him.

Caleb clapped one hand to his cheeks in mock dismay. “Can I try again?”

“Two more,” Amelia agreed, “and then it’s my turn again.”

He spun back around and closed his eyes. “Two!” he declared and let it fly.

There was a plop and a shocked gasp. When Caleb opened his eyes, it was to see Martha Coblentz—the other preacher’s wife—standing in the doorway that opened to the utility room, her hands full, her mouth opening and closing like a beached fish.

Well, it should be, Caleb thought as familiar heat washed over his neck and face. The beanbag had landed on Martha’s head and appeared to be lodged in her prayer kapp. The shame he felt at being caught in the midst of such childish play was almost as great as his overwhelming urge to laugh. “I’m sorry,” he exclaimed, covering his amusement with a choking cough. “It was a game. My daughter... We... I was teaching her English...counting...”

Martha drew herself to her full height and puffed up like a hen fluffing her feathers. The beanbag dislodged, bounced off her nose and landed on the floor. “Well, I never!” she said as her gaze raked the kitchen, taking in Rebecca, the colander, the biscuits on the stove and the pumpkin lollipop on the table. Martha sniffed and sent the beanbag scooting across the clean kitchen floor with the toe of one sensible, black-leather shoe. “Hardly what I expected to find here.” Her lips pursed into a thin, lard-colored line. “Thought you’d want something hot...for your supper.”

Caleb realized that Martha wasn’t alone. A younger woman—Martha and Reuben’s daughter, Doris, Dorothy, something like that—stood behind her, her arms full of covered dishes. She shifted from side to side, craning her thin neck to see past her mother.

“Come in,” Caleb said. “Please. Have coffee.”

“Aunt Martha. Dorcas.” Rebecca, not seeming to be the least bit unsettled by their arrival, smiled warmly and motioned to them. “I know you have time for coffee.”

“Your mother said you were only here while Preacher Caleb was at the shop,” Martha said. “I didn’t expect to find such goings-on.”

“We came to bring you stuffed beef heart.” Dorcas offered him a huge smile. One of her front teeth was missing, making the tall, thin girl even plainer. “And liver dumplings.” The young woman had a slight lisp.

Caleb hated liver only a little less than beef heart. He swallowed the lump in his throat and silently chided himself for being so uncharitable to two of his flock, especially Dorcas, so obedient and modestly dressed. He had a long way to go to live up to his new position as preacher for this congregation.

“And molasses shoofly pie,” Martha added proudly, holding it up for his approval. “Dorcas made it herself, just for you.” She strode to the table, set down the dessert and picked up the questionable pumpkin lollipop by the end of the ribbon. Holding it out with as much disgust as she might have displayed for a dead mouse attached to a trap, Martha carried the candy to the trash can and dropped it in. “Surely, you weren’t going to allow your child to eat such English junk,” she said, fixing him with a reproving stare. “Our bishop would never approve of jack-o’-lantern candy, but of course, I’d never mention it to him.”

“Pumpkin,” Rebecca said, defending the lollipop. “We were going to wash off the face.”

Martha sniffed again, clearly not mollified.

Amelia’s lower lip quivered. She cast one hopeful glance in Caleb’s direction, and when he gave her the father warning look, she turned and pounded out of the room and up the stairs. Fritzy—cowardly dog that he was—fled, hot on the child’s heels.

Rebecca went to the stove and turned off the oven. “You’re right, Aunt Martha,” she said sweetly. “It is time I went home.”

Martha scowled at her.

“Eight on Monday?” Rebecca asked Caleb.

“Eight-thirty,” he answered.

Rebecca collected the colander and the beanbags, made her farewells to her aunt and cousin and vanished into the utility room. “See you Sunday for church.”

Martha bustled to the stove, shoved Rebecca’s pan of biscuits aside and reached for one of the containers Dorcas carried. “Put the dumplings there.” She indicated the countertop. “They’re still warm,” Martha explained. “But they taste just as good cold.”

Probably not, Caleb thought, trying not to cringe. He liked dumplings well enough, although the ones the women cooked here in Delaware—slippery dumplings—were different than the ones he’d been served in Idaho. He certainly couldn’t let good food go to waste, but he wasn’t looking forward to getting Amelia to eat anything new. The beef heart would certainly be a challenge. His daughter could be fussy about her meals. Once she’d gone for two weeks on nothing but milk and bread and butter. That was her “white” phase, he supposed. And the butter only passed the test because it was winter and the butter was pale.

“We wondered how you were settling in,” Martha said. “Such a pity, losing your wife the way you did. Preachers are generally married. I’ve never heard of one chosen who was a single man, but the Lord works in mysterious ways. He has His plan for us, and all we can do is follow it.”