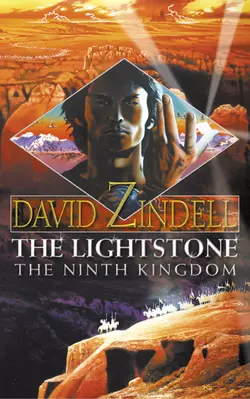

The Lightstone: The Ninth Kingdom: Part One

David Zindell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фольклор

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the author of Neverness comes a powerful new epic fantasy series. The Ea Cycle is as rich as Tolkien and as magical as the Arthurian myths.The world of Ea is an ancient world settled in eons past by the Star People. However, their ancestors floundered, in their purpose to create a great stellar civilisation on the new planet: they fell into moral decay.Now a champion has been born who will lead them back to greatness, by means of a spiritual – and adventurous – quest for Ea’s Grail: the Lightstone.His name is Valashu Elahad, and he is destined to become King. Blessed (or cursed?) with an empathy for all living things, he will lead his people into the lands of Morjin, into the heart of darkness, wielding a magical sword called Alkadadur, there to recover the mythical Lightstone and return in triumph with his prize.But Morjin is not to be vanquished so easily…