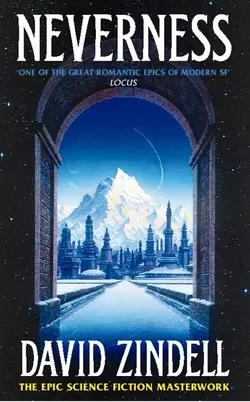

Neverness

David Zindell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1104.26 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An epic masterwork of science fiction, Neverness is a stand-alone novel from one of the most important talents in the genre.