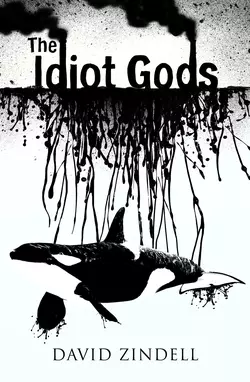

The Idiot Gods

David Zindell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 820.87 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Quite simply the best book about a whale since Moby Dick.The Idiot Gods is an epic tale told by an orca. David Zindell returns to the grand themes of Neverness in this uniquely moving book.An epic tale of a quest for a new way of life on earth, told by an orca.When Arjuna of the Blue Aria Family encounters three signs of cataclysm, he leaves his home in the Arctic Ocean to seek out the Idiot Gods and ask us why we are destroying the world. But the whales’ ancient Song of Life is beyond our understanding, and we know nothing of the Great Covenant between our kinds. Arjuna is captured, starved, tortured and made to do tricks in a tiny pool at Sea Circus.His love for a human linguist gives him hope, even as he despairs that other people twist his words and continue the worldwide slaughter. As the whales′ beloved Ocean turns toward the Blood Solstice the fate of humanity hangs in the balance: for if Arjuna gains the Voice of Death he could destroy mankind. But if understanding can prevail, he may, through the whales’ mysterious power of quenging, create a new Song of Life and enable human evolution to unfold.