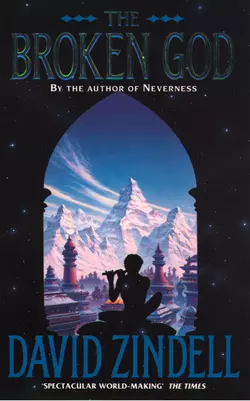

The Broken God

David Zindell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 930.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Book One of David Zindell’s epic trilogy set in Neverness, legendary City of Light, where inner space and outer space meet … where the god programme is up and running.Into its maze of colour-coded streets of ice a wild boy stumbles, starving, frostbitten and grieving, a spear in his hand: Danlo the Wild, a messenger from the deep past of man. Brought up from Neverness by the Alaloi people, Neanderthal cave-dwellers, Danlo alone of his tribe has survived a plague – because he is not, as he thought, a misshaped Neanderthal, but human with immunity engineered into his genes. He learns that the disease was created by the sinister Architects of the Universal Cybernetic Church. The Architects possess a cure which can save other Alaloi tribes. But the Architects have migrated to the region of space known as the Vild, and there they are killing stars.All of civilisation has converged on Neverness through the manifold of space travel. Beyond science, beyond decadence, sects and disciplines multiply there. Danlo, his mind shaped by the primitive man, brings to Neverness a single long-lost memory that will change them all.