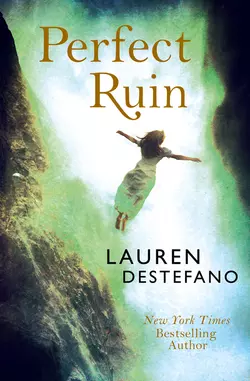

Perfect Ruin

Lauren DeStefano

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Историческое фэнтези

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 536.55 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the New York Times bestselling author of The Chemical Garden trilogy: On the floating city of Internment, you can be anything you dream. Unless you approach the edge.Morgan Stockhour knows getting too close to the edge of Internment, the floating city in the clouds where she lives, can lead to madness. Even though her older brother, Lex, was a Jumper, Morgan vows never to end up like him. If she ever wonders about the ground, and why it is forbidden, she takes solace in her best friend, Pen, and in Basil, the boy she’s engaged to marry.Then a murder, the first in a generation, rocks the city. With whispers swirling and fear on the wind, Morgan can no longer stop herself from investigating, especially once she meets Judas. Betrothed to the victim, he is the boy being blamed for the murder, but Morgan is convinced of his innocence. Secrets lay at the heart of Internment, but nothing can prepare Morgan for what she will find – or whom she will lose.