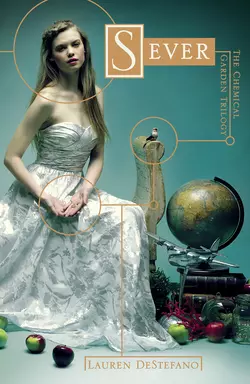

Sever

Lauren DeStefano

The third and final novel in Lauren DeStefano’s breathtaking dystopian romance series, The Chemical Garden TrilogyTime is running out for Rhine.With less than three years left until the virus claims her life, Rhine is desperate for answers. Having escaped torment at Vaughn’s mansion, she finds respite in the dilapidated home of her husband’s uncle, an eccentric inventor who hates Vaughn almost as much as Rhine does.Rhine’s determination to be reunited with her twin brother, Rowan, increases as each day brings terrifying revelations to light about his involvement in an underground resistance. She realizes must find him before he destroys the one thing they have left: hope.In this breathtaking conclusion to Lauren DeStefano’s The Chemical Garden trilogy, everything Rhine knows to be true will be irrevocably shattered. But what she discovers along the way has alarming implications for her future – and about the past her parents never had the chance to explain.

For

Riley,

Isaiah,

Isabella,

Hailey,

Cameron,

Mary,

Cooper,

Eliot,

and

Raina,

Who have a lifetime

Of roads before them

I must lose myself in action,

lest I wither in despair.

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u66aed885-cc32-5ec1-ab01-28c6b766fc91)

Dedication (#u1952c8f8-c638-54f5-8867-e8bd584ce16d)

Epigraph (#u65dee45e-cde5-5ae4-ae51-392af0bc10ef)

Chapter 1 (#u7c98558a-4268-59f3-90e1-88e2c4d5fe77)

Chapter 2 (#u9bb8bfbf-cfd8-55f6-974f-fd882c7f7dc5)

Chapter 3 (#u00b4b3f6-3117-5021-b8e2-657c9b16d1a4)

Chapter 4 (#u57cfb4ed-b274-5463-9e2a-cd59b9ab5d98)

Chapter 5 (#u620c8c62-2e97-5eea-a2a9-7bda93a95e31)

Chapter 6 (#u0864710b-3508-5e32-a1e1-2bced55bdc40)

Chapter 7 (#u04975763-ffb6-5805-ad0b-ec9d40576986)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise for the Chemical Garden Trilogy (#litres_trial_promo)

By Lauren DeStefano (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1

IN THE ATLAS the river still flows. The thin line of it carries cargo to a destination that no longer exists. We share a name, the river and I; if there’s a reason for this, it died with my parents. The river lingers in my daydreams, though. I imagine it spreading out into the greatness of the ocean, melting into sunken cities, carrying old messages in bottles.

I have wasted too much time on this page. Really I should be in North America, charting my way from the Florida coastline to Providence, Rhode Island, where my twin brother has just bombed a hospital for its pro-science research on embryos.

I don’t know how many are dead because of him.

Linden shifts his weight restlessly. “I didn’t even know you had a brother,” he’d said when I told him where I was going. “But the list of things I don’t know about you is growing longer every day, isn’t it?”

He’s bitter. About our marriage and the way it ended. About the way it’s not really over.

My sister wife looks out the window, her hair like light through autumn leaves. “It’s going to rain,” she says quietly. She’s here only at my insistence. My once-husband still doesn’t quite believe she was in danger in his father’s, Vaughn’s, home. Or maybe he does believe it; I’m not sure, because he’s barely speaking to me these days, except to ask how I’m feeling and to tell me I’ll be discharged from the hospital soon. I should consider myself lucky; most of the patients here are crammed into the lobbies or a dozen to a room, and that’s if they’re not turned away. I have comfort and privacy. Hospitalization of this class is reserved for the wealthy, and it just so happens that my father-in-law owns nearly every medical facility in the state of Florida.

Because there is never enough blood for transfusions, and because I lost so much of it when I sawed into my leg in a maddened delirium, it took me a long time to recover. And now that my blood has regenerated, they want to take it a bit at a time and analyze it to be sure I’m recovering. They’re under the assumption that my body didn’t respond to Vaughn’s attempts to treat the virus; I’m not sure what exactly he told them, but he has a way of being everywhere without being present.

I have an interesting blood type, they say. They wouldn’t have been able to find a match even if more people donated their blood for the meager pay the hospital gives.

Cecily mentioned the rain to distract Linden from the nurse who has just sterilized my arm. But it doesn’t work. Linden’s green eyes are trained on my blood as it fills up the syringe. I hold the atlas in my blanketed lap, turn the page.

I find my way back to North America—the only continent that’s left, and even it isn’t whole; there are uninhabitable pieces of what used to be known as Canada and Mexico. There used to be an entire world of people and countries out there, but they’ve all since been destroyed by wars so distant they’re hardly spoken about.

“Linden?” Cecily says, touching his arm.

He turns his head to her, but doesn’t look.

“Linden,” she tries again. “I need to eat something. I’m getting a headache.”

This gets his attention because she is four months pregnant and prone to anemia. “What would you like, love?” he says.

“I saw brownies in the cafeteria earlier.”

He frowns, tells her she should be eating things with more sustenance, but ultimately succumbs to her pouting.

Once he has left my hospital room, Cecily sits on the edge of my bed, rests her chin on my shoulder, and looks at the page. The nurse leaves us, my blood on his cart of surgical utensils.

This is the first time I’ve been alone with my sister wife since arriving at the hospital. She traces the outline of the country, swirls her finger around the Atlantic in tandem with her sigh.

“Linden is furious with me,” she says, not without remorse, but also not in her usual weepy way. “He says you could have been killed.”

I spent months in Vaughn’s basement laboratory, the subject of countless experiments, while Linden obliviously milled about upstairs. Cecily, who visited me and talked of helping me escape, never told him about any of it.

It isn’t the first time she betrayed me; though, as with the last time, I believe that she was trying to help. She would botch Vaughn’s experiments by removing IVs and tampering with the equipment. I think her goal was to get me lucid enough to walk out the back door. But Cecily is young at fourteen years old, and doesn’t understand that our father-in-law has plans much bigger than her best efforts. Neither of us stands a chance against him. He’s even had Linden believing him for all these years.

Still, I ask, “Why didn’t you tell Linden?”

She draws a shaky breath and sits more upright. I look at her, but she won’t meet my eyes. Not wanting to intimidate her with guilt, I look at the open atlas.

“Linden was so heartbroken when you left,” she says. “Angry, but sad, too. He wouldn’t talk about it. He closed your door and forbade me from opening it. He stopped drawing. He spent so much time with me and with Bowen, and I loved that, but I could tell it was because he wanted to forget you.” She takes a deep breath, turns the page.

We stare at South America for a few seconds. Then she says, “And, eventually, he started to get better. He was talking about taking me to the spring expo that’s coming up. Then you came back, and I thought, if he saw you, it would undo all the progress he’d made.” Now she looks at me, her brown eyes sharp. “And you didn’t want to be back, anyway. So I thought I could get you to escape again, and he would never have to know, and we could all just be happy.”

She says that last word, “happy,” like it’s the direst thing in the world. Her voice cracks with it. A year ago, here is where she’d have started to cry. I remember that on my last day before I ran away, I left her screaming and weeping in a snowbank when she realized how she’d betrayed our older sister wife, Jenna, by telling our father-in-law of Jenna’s efforts to help me escape, which only aided his decision to dispose of her.

But Cecily has grown since then. Having a child and enduring the loss of not one but two members of her marriage have aged her.

“Linden was right,” she says. “You could have been killed, and I—” She swallows hard, but doesn’t take her eyes from mine. “I wouldn’t have been able to forgive myself. I’m sorry, Rhine.”

I wrap my arm around her shoulders, and she leans against me.

“Vaughn is dangerous,” I say into her ear. “Linden doesn’t want to believe it, but I think you do.”

“I know,” she says.

“He’s tracking your every move the way he tracked me.”

“I know.”

“He killed Jenna.”

“I know. I know that.”

“Don’t let Linden talk you into trusting him,” I say. “Don’t put yourself in a situation where you’re alone with him.”

“You can run away, but I can’t,” she says. “That’s my home. It’s all I have.”

Linden clears his throat in the doorway. Cecily bounds to him and ups herself on tiptoes to kiss him when she takes the brownie from his hand. Then she unwraps its plastic. She settles in a chair and props her swollen feet up on the window ledge. She has a way of ignoring Linden’s hints about wanting to be alone with me. It was a minor annoyance in our marriage, but right now it’s a relief. I don’t know what Linden wants to say to me, only that his fidgeting means he wants it to be in private, and I’m dreading it.

I watch as Cecily nibbles the edges of the brownie and dusts crumbs off her shirtfront. She’s aware of Linden’s restlessness, but she also knows he won’t ask her to leave. Because she’s pregnant, and because she’s the only wife left who so genuinely adores him.

Linden picks up the sketchbook he abandoned on a chair, sits, and tries to busy himself looking through his building designs. I sort of feel sorry for him. He has never been authoritative enough to ask for what he wants. Even though I know this conversation he’s itching to have will leave me feeling guilty and miserable, I owe him this much.

“Cecily,” I say.

“Mm?” she says, and crumbs fall from her lips.

“Leave us alone for a few minutes.”

She glances at Linden, who looks at her and doesn’t object, and then back to me.

“Fine,” she sighs. “I have to pee anyway.”

After she leaves, closing the door behind her, Linden shuts his notebook. “Thanks,” he says.

I push myself upright, smooth the sheets over my thighs, and nod, avoiding his eyes. “What is it?” I ask.

“They’re letting you out tomorrow,” he says, taking the seat by my bed. “Do you have any sort of plan?”

“I was never good at plans,” I say. “But I’ll figure it out.”

“How will you find your brother?” he says. “Rhode Island is hundreds of miles away.”

“One thousand three hundred miles,” I say. “Roughly. I’ve been reading up on it.”

He frowns. “You’re still recovering,” he says. “You should rest for a few days.”

“I might as well get moving.” I close the atlas. “I have nowhere else to go.”

“You know that isn’t true,” he says. “You have a—” He hesitates. “A place to stay.”

He was going to say “home.”

I don’t answer, and the silence is filled with all the things Linden wants to say. Phantom words, ghosts that haunt the pieces of dust swimming in beams of light.

“Or,” he starts up again. “There is another option. My uncle.”

That gets me to look at him, maybe too inquisitively, because he seems amused. “My father disowned him years ago, when I was very young,” he says. “I’m supposed to pretend he doesn’t exist, but he doesn’t live far from here.”

“He’s your father’s brother?” I say, skeptical.

“Just think about it,” Linden says. “He’s a little strange, but Rose liked him.” He says that last part with a laugh, and his cheeks light up with pink, and I strangely feel better.

“She met him?” I ask.

“Just once,” Linden says. “We were on our way to a party, and she leaned over the driver’s seat and said, ‘I’m sick of these boring things. Take us anywhere else.’ So I gave the driver my uncle’s address, and we spent the evening there, eating the worst coffee crumb cake we’d ever tasted.”

It’s the first time since her death that he’s brought up Rose without wincing at the pain.

“And the fact that my father hates him just made my uncle that much more appealing to her,” Linden goes on. “He’s too pro-naturalism for my father’s taste, and admittedly a little strange. I’ve had to keep it a secret that I visit with him.”

Linden has a rebellious side. Who knew. He reaches out and tucks my hair behind my ear. It’s done out of habit, and he jerks his hand back when he realizes his mistake.

“Sorry,” he mumbles.

“It’s all right,” I say. “I’ll think about it.” My words are coming out fast, bumbling. “What you said—I mean—I’ll think about it.”

2

CECILY HANGS out the limo’s open window, her hair flailing behind her like a ribbon caught on a hook. Bowen, in his father’s arms, reaches out to catch it. I’m astounded by how much he grew while I was away. He’s a teddy bear of a boy—stocky and friendly and apple-cheeked. He was born with dark hair and beaming blue eyes that have since gone hazel. His hair has lightened to a coppery blond that I imagine mimics Cecily’s when she was a baby, which we’ll never know for certain. He has her defiant chin, her thin eyelashes. With every day that passes, prominent traces of Linden dissolve from his face.

He is beautiful, though. And Cecily is mad for him. I’ve never seen anyone love anything as much as she loves that baby. Even now, though she’s facing the sky that rushes past, she’s singing a lullaby for him. I recognize it as a poem from a book in the library on the wives’ floor. Jenna used to read it aloud.

And frogs in the pools singing at night,

And wild plum-trees in tremulous white;

Robins will wear their feathery fire

Whistling their whims on a low fence-wire …

The sun is setting, making the world orange. I rub my fists over my knees, uneasy. I can’t believe Vaughn let us use the limo for this. Maybe he’s trying to stay on Linden’s good side, to manipulate him by being contrite and reliable. I keep expecting the driver to turn on us and take me back to the mansion. But he has taken us so far into the countryside that I’m beginning to let go of that fear. It’s been minutes since we passed any buildings. There’s only grass, and the occasional lone tree that comes and goes like an explosion.

Cecily interrupts her song to ask, “Where are we?” and lean back into her seat.

“Someplace rural,” Linden says. “It’s hard to say. I never knew the street names.”

Cecily reaches for the baby, and then holds him over her head, blowing absurd-sounding kisses on his belly; his giggles make her grin.

“It’s this turn,” Linden tells the driver. “Off the road. Follow the tire tracks.”

Even the limo, with its smooth ride, jostles over the uneven terrain. And a few minutes later we’ve come to the only thing in sight: a two-story brick house that looks as old and stable as the mansion, but much smaller. Surrounding it are half a dozen tarps arranged like black car-shaped ghosts. There’s a dilapidated shed and a windmill. The roof is covered in reflective panels.

Cecily crinkles her nose and turns to Linden. “We can’t leave her here,” she says. “It looks like a junkyard.”

“It’s not as bad as all that,” he says.

“There’s tinfoil on his roof!”

“They’re solar panels,” Linden amends patiently. “So he doesn’t have to use so much electricity.”

Cecily opens her mouth to object, but I say, “It’s only for a couple of days. It looks fine.” I don’t mention that, while this is a step down from the luxuries of the mansion, it’s as nice as any of the homes I grew up near. And solar panels aren’t uncommon in Manhattan at all, where many can’t afford electricity.

The limo stops, and I open my door quickly, afraid of sleeping gas or locks or snakes that could come slithering through the vents to strangle me.

It’s early evening now, and without civilization for miles I can see darkness stretching toward me from every direction. The stars are bright, splayed across every shade of pink and blue, tracing a lone, oblong cloud.

Linden comes up beside me, follows my gaze skyward. “When I was little,” he says, “my uncle told me the names of all the constellations. But I could never find them.”

“But you know which one’s the North Star,” I remind him. I remember that he told Cecily about it, and she was discouraged by his lack of romance.

“Right there,” he says, following the line of my arm as I point.

“That’s the tail of Ursa Minor,” I say, moving my finger along the corresponding stars. “It’s my favorite because I think it looks like a kite.”

“I actually see it,” he says quietly, as though astonished. “But I thought Ursa Minor was supposed to be in the shape of a dipper.”

“Well, I think it looks like a kite,” I say. “That’s how I’m always able to find it.”

He turns toward me, and I can feel his breaths, so faint and unassuming that they only move the finest hairs around my face. I don’t dare take my eyes from the stars. My heart is pounding. Memories rush through me. Memories of his fingers unbuckling my shoes, inching under the strap of my red party dress. His lips on mine. The darkness of my bedroom swimming with ivy and champagne glasses the night we came home late from the expo. Snow dusting his shoulders and his dark hair the night we said good-bye.

Cecily slams the car door, snapping me back to reality. “If Rhine is staying here tonight,” she says, “I am too, to make sure she doesn’t get murdered by whatever lunatic runs this place.”

I open my mouth to chide her for being so rude. To say that Linden’s uncle was nice enough to let me stay, and that asking for anything more would seem ungrateful. And also to point out that she’s barely as high as my shoulder, and how exactly would she fend off a lunatic if I couldn’t?

But the words won’t come out. The thought of my only remaining sister wife going back to that mansion is making my palms sweat. She was safe when Vaughn kept her oblivious, but now that she’s seen the workings of his basement and she understands what he’s capable of, I worry for her safety.

“My uncle isn’t a lunatic,” Linden says, and opens the car door again to pull out the suitcase that was sliding around the floor on the way here.

“Why does your father hate him so much, then?” Cecily says.

Linden’s father is no judge of who is or is not a lunatic, but I don’t say this either. I lean back against the trunk of the limo because I’m starting to feel light-headed, and the stars are throbbing, and Linden is right, I do need to rest before I venture into the world again. Everywhere I look, there’s nothing. The world is so far away. All that effort, all those miles undone. I was in Vaughn’s basement of horrors for more than two months. Two months that felt like ten minutes. Gabriel must think I’m dead. Just like my brother thinks I’m dead.

But there has been so much sadness, so much disheartenment, that my body has worked up a defense mechanism to keep me from thinking about it. My head goes numb, and my bones start to ache. Hurricane winds spiral in my ear canals. A sharp pain has streaked my vision with a lightning bolt of white.

Cecily and Linden are talking—something about what counts as eccentricity versus insanity, I think, and the conversation is getting terse as they interrupt each other. Linden is a creature of saintlike patience, but Cecily has a way of wearing anyone down.

“You okay?” Cecily asks me, and I realize that they’ve moved a couple of yards ahead of me, toward the house. Linden turns to watch me, Bowen’s diaper bag slung from his shoulder, and a suitcase in his hand; he packed some clothes for me from my old closet.

I nod and follow after them.

Nobody answers when Linden knocks on the door. He knocks harder, then tries looking into the only visible window, which has its shade drawn. “Uncle Reed?” he calls, and knocks on the glass.

“Does he know we’re coming?” I ask.

“I told him last week when I visited,” he says.

“How often do you come out here?” Cecily says, wounded. “You never told me.”

“I’ve kept it secret. …” Linden trails off, mouthing something to himself as he tries to see around the window shade. “I think I see a light inside.” He knocks again, and when there’s no answer, he opens the door.

Cecily cradles Bowen’s head protectively, and casts a pensive stare into the darkness. “Linden, are you sure?” But he has already gone in ahead of us.

I follow him, my sister wife shuffling close behind and gripping the hem of my shirt.

It’s so dark that I can barely make out Linden’s shape as it moves ahead of me. It’s a long hallway, the wood creaking under our feet, and there’s the smoky smell of cedar and must. Then there’s a faint orange light flickering in a room at the end of the hall.

We gather at either side of Linden in the doorway. We’ve come to a kitchen—at least I think that’s what it is. There’s a sink and a stove. But rather than cabinets there are shelves cluttered with things I can’t make out in the darkness.

There’s a small round table, upon which a candle flickers in a mason jar. A man is seated there, hunched over something that looks like a giant metal organ. Its wires, pipes, and gears are the arteries, and it’s a mechanical heart, bleeding black oil onto the table and the man’s fingers.

“Uncle Reed?” Linden says.

The man grunts, working some intricacy with a pair of pliers and taking his time before looking up. He sees me first, then Cecily. “These are your wives?” he says.

Linden hesitates. But he doesn’t have to answer, because the man returns to his work rather unceremoniously and adds, “I thought you said there were three of them.”

“Just two,” Linden says, with so little emotion it gives me pause. It’s as if Jenna never existed. “And this is my son,” he adds, taking the baby from Cecily’s arms. “Bowen.”

The man—Reed—pauses, astonished by something. But then he only grunts. “Doesn’t look like you,” he says.

Cecily plays with a light switch on the wall; it doesn’t work. “Please don’t touch anything,” Reed says, and wipes his hands with a dingy rag that only spreads the oil around. He moves to the sink, and the faucet shudders before it spits out an unsteady stream. I can’t be certain in the candlelight, but I think I see flecks of black in the water. Reed mutters curses.

Then he pulls a cord over his head, and bleary light fills the room from a bulb that swings from the ceiling. The shadows jump back and forth, animating jars and pipes and senseless pieces that fill the shelves. There’s a refrigerator in one corner of the room, but there’s no electrical hum to it, no indication that it’s on.

Reed comes closer, inspects the child in Linden’s arms. Bowen’s eyes are dazed, transfixed on the swinging bulb. “Nope, nothing like you,” Reed reaffirms. “Whose is he?”

“He’s mine,” Cecily says.

Reed snorts. “How old are you? Ten?”

“Fourteen,” she says through gritted teeth.

I get a whiff of something heady and smoky when Reed moves to stand before me. It’s making my eyes water, but I’m just grateful that he looks nothing like Vaughn. He’s not as tall, and he’s a little overweight, and his gray hair is as wild as waves breaking on rocks. “I thought you were dead,” he says to me.

I must be worse off than I thought, because surely I just imagined that. But then Linden says, “That isn’t Rose, Uncle. Her name is Rhine. Remember I told you the other day?”

“Oh, right, right,” Reed says. “I’m bad with names. I’m usually much better with faces.”

“I’ve been told I look like her,” I offer.

“Doll, you could be her ghost,” Reed says. “Do you believe in reincarnation?”

“She can’t be a reincarnation of Rose,” Cecily says, indignant. “They were both alive at the same time.”

Reed looks at her like she’s something he just stepped in, and she inches closer to Linden’s side.

“Tell me,” Reed says, turning back to me, “because my nephew’s story was confusing. You’re running away from him, and he’s helping you?”

“That’s one way to put it,” I say. “But I’m not running away. Not really. I’m looking for my brother.” A lump is forming in my throat, caused by Reed’s stare and his smell and the interrogating hue of that light. “The last I heard, he was in Rhode Island. He’s gotten into a—situation, and I need to find him. I won’t be any trouble in the meantime.” My words are coming out one atop the other, fast, and Linden puts his hand on my arm, and for some reason it calms me.

Reed looks me over, his mouth squished to one side of his face like he’s thinking. “You have too much hair,” he says. “You’ll have to tie it back so it won’t get caught in the machines.”

I have no idea what he’s talking about, but I say, “Okay.”

“I told him you would help out a little,” Linden says. “It won’t be anything arduous. He knows you’re recovering.”

“From the car accident. Right,” Reed says. I don’t know what story Linden fed him to explain my injuries, but judging from his tone he doesn’t believe it, or care to. “There’s a room upstairs where you can put your things. My nephew can show you. The floors make a terrible creaking, so I’ll have to ask you not to walk around at night.”

That’s apparently our cue to leave, because he turns his attention to the contraption on the table. Linden herds us down the hallway.

“Oh, Linden,” Cecily whispers, her words almost lost to the creaking of the steps. “I knew you were mad at her, but you can’t be serious about leaving her here.”

“I am doing Rhine a favor,” he replies. “And she can take care of herself.” He looks over his shoulder at me. I’m two steps behind him. “Can’t you?” he says.

I nod like I’m not at all unnerved by this new cold side to him. Not cruel like his father. Not warm like the husband who sought me out on quiet nights. Something in between. This Linden has never woven his fingers through mine, never chosen me from a line of weary Gathered girls, never said he loved me in a myriad of colored lights. We are nothing to each other.

Reed may have forgotten my name, but he apparently remembered that I was coming, because the spare bedroom is lit up by three candles—one on the nightstand, two on the dresser. They and a twin bed are the only furniture in the room. There’s a cracked mirror on the far wall, and my reflection drowns in the darkness of it. Rose’s ghost. I almost expect it to move independent of me.

Cecily drops the suitcase and the diaper bag on the floor, and a cloud of dust bursts from the mattress when she sits on it. She makes a big show of choking on it.

“It’s fine,” I say, shaking out the pillow.

“I’m afraid to even ask if there’s a bathroom I can use,” Cecily says.

“At the end of the hall,” Linden says, rubbing his index finger along the bridge of his nose; it’s something I’ve only seen him do when he’s frustrated with his drawings. “Take a candle with you.”

After Cecily has left the room, I sit on the edge of the bed and say, “Thank you, Linden.”

He looks at his reflection in the mirror. “My uncle won’t ask any questions, if you don’t,” he says. “About why you aren’t staying at home with me, that is.”

The silence is tight and unnatural. I grip the blanket in my fists and say, “Are you and Cecily going back there?”

“Of course,” he says.

He still won’t believe me about everything that happened in the basement. About Deirdre. I vaguely remember whispering about her in my medicated delirium, and about Jenna’s body hiding away in some freezer. He rubbed my arm, whispering words that sounded like moth bodies flying into glass windows. Nonsensical things I tried to cling to. Maybe, lying there, I was so pitiful that he felt no choice but to love me. Now he says I can take care of myself. Now I’m the liar trying to destroy the perfect world his father set up for him, who ran away, broke everything. And it’s getting late, and it’s time to part ways.

But the words come out of me anyway. “Don’t go.”

He looks at me.

“Don’t go,” I say. “And don’t take Cecily back there. I know you don’t believe me, but I have a terrible feeling that—”

“I can take care of Cecily,” he says. “I would have taken care of you, too. If I’d known you were so worried about my father.”

Bowen has fallen asleep against Linden’s chest, and Linden shifts him to the other arm. “My father thought that if you didn’t want to be married to me, he could have you. It’s because of your eyes. He wanted to study them, and he took it too far. He can be that way.” His eyebrows knit together, and he looks at his feet, struggling to make sense of what he’s saying, to force logic where there is none. “He isn’t the monster you think he is. He just—he gets so into his work that he forgets people are people. He gets carried away.”

“Carried away?” I spit back. “He drove needles into my eyes, Linden! He murdered a newborn—”

“Don’t you think I know my own father?” he interrupts. “I’d trust him before I’d believe anything you say. You couldn’t even do me the dignity of telling the truth.”

There was a night, months ago, when I almost did. It was after the expo. I was half-drunk, my hair sticky and perfumed and teased, the bed tipping under me. He climbed over my body, and he kissed me. I could hear tree branches murmuring to one another in the moonlight. And Linden said, so close that I could feel his breath on my eyelashes, But I don’t know who you are. I don’t know where you came from. His eyes were bright. I wanted so badly to tell him, but something about that entire night seemed so beautiful, so bizarre, that I didn’t trust it with my secrets. Or maybe I just wanted to play along, to wear his ring and be his wife for a little while before the magic took the light from the moon.

Now I say nothing. There’s no brightness in his eyes for me.

“If you didn’t love me,” he says, “you should have said it. I would have let you go.”

“You might have,” I admit. “But not your father.”

“My father has never been in charge of what I do,” he says.

“Your father has always been in charge of what you do,” I say.

He looks at me, and I stop breathing. Something comes surging up behind his eyes, some argument of love or vengeance. Something that’s been building every second I’ve been away. And I want it, whatever it is. Want to hold it in both hands like his leaping heart that’s been ripped from his chest. Want to warm it with my body heat.

He says, “When Cecily comes back, tell her I’ll be waiting by the car.”

Then he’s gone.

“I don’t want to leave you here,” Cecily says when I relay the message. “This place looks like it could give you cancer or something.” She’s remembering that word, “cancer,” from a soap opera Jenna used to watch. It’s a disease that was eliminated from our genetics.

“I don’t think cancer was something you could catch,” I tell her.

“That’s my point,” she says.

We must be making too much noise, because Reed bangs on the ceiling.

Cecily huffs and sits on the bed next to me. After a few seconds she puts her arm around my shoulders and stares at her stomach. At four months along she’s already looking tired and swollen. Her cheeks and fingertips are flushed. Her face and hair are damp from where she’s splashed herself with cold water, something she does after a bout of nausea.

“Have you been sick a lot?” I ask her.

“It’s not so bad,” she says softly. “Linden takes care of me.”

I’m worried about her. I wonder if it has even occurred to her or to Linden that she hardly had a rest between pregnancies. Vaughn surely knows how unsafe this is, and he allowed it, which worries me even more. I’m scared that she’ll enter that dark hall, descend the stairs, and be forever in Vaughn’s clutches. I think she’s scared too, because she doesn’t move. I don’t know how much time passes before Linden comes looking for her.

“Ready to go?” He stands in the doorway, mostly in shadow.

“I’m staying the night,” she says.

They have some sort of conversation with their eyes. A husband-and-wife thing—something I could never quite get the hang of. Cecily wins, because Linden picks up the diaper bag and says, “I’ll be back for you in the morning, first thing.”

A few minutes later, through the window, we watch the limo drive out of sight.

The mattress is lumpy and hard, and Cecily, who is back to snoring the way she did in her later trimesters, spends the night thrashing and turning. She kicks me so many times that I eventually take a pillow and settle on the floor. But every position on the hard wood aggravates the recovering gash in my thigh. In my dreams, it bleeds and seeps through the floorboards, and Reed pounds on the ceiling because blood is raining down on his work. The engine on the table comes to life. It pulses and breathes.

In the darkness Cecily whispers my name. At first I think it’s part of my dream, but she persists, increasing in frequency and intensity until I say, “What?”

“Why are you on the floor?” I can just make out her face and arm leaning over the mattress, tangle of hair coming over one shoulder.

“You were kicking,” I say.

“I’m sorry. Come back up. I promise I won’t anymore.”

She makes room for me, and I cram in beside her. Her skin is sticky and hot. “You shouldn’t wear socks to bed,” I tell her. “They keep heat in. Last time you were pregnant, you always got feverish at night.”

Her legs move under the blanket as she kicks her socks off. It takes her a while to get comfortable, and I can tell she’s trying not to disturb me, so I don’t complain as I’m knocked around the mattress. Eventually she settles on her side, facing me.

“Did you get sick earlier, when you went to use the bathroom?” I ask.

“Don’t tell Linden,” she says, yawning. “He’s squeamish about that stuff. He worries.”

That’s to be expected after what happened with Rose’s pregnancy. But it’s not as though I can tell her that. And soon I find, despite my worries, that I’m exhausted enough to fall asleep.

Just as I’m beginning to dream, she says, “I think about those other girls in the van with us. The ones who were killed.”

My dreams fade away from me, and I wish desperately that they’d return. Even a nightmare would be welcome over that memory. It’s not something my sister wives and I ever talked about, the odd and horrific thing that bonded us to one another. I especially wouldn’t expect to hear about it from Cecily, who has always wanted to be the happy housewife.

“I just wanted you to know that,” she says. “I’m not a monster.”

I turn my head to look at her. “Of course you aren’t.”

“You called me one,” she says. “The day you ran away.”

“I was upset,” I say, pushing the sweaty hair from her face. “But what happened to Jenna isn’t your fault.”

She draws a shaky breath, closes her eyes for a long moment. “Yes, it is.”

Here is where I expect her to cry, but she doesn’t. She only looks at me. And it strikes me again how much she’s grown in my absence. Maybe she had no choice. There were no sister wives to console her, the father-in-law she trusted had only been using her, and it’s not as though she could explain any of this to her husband.

I struggle for words of comfort, but nothing feels sincere enough. And no matter what I say, Jenna is still gone, and so are the other girls that were Gathered, and the girl Silas and I found lying in a ditch. Cecily still won’t live to see Bowen grow, and my brother has spiraled out of control in his grief, and I’m no closer to finding him than I was last year.

I am entirely powerless.

“The whole time we were married, I treated you like you were too small to understand what was happening to us,” I say. “But I felt small too. I couldn’t control the way things were any more than you could.”

“You looked so confident,” she says. “I envied you from the day we were married. I’ve decided I’m going to be more like you.” She says it with conviction. “I’m going to be stronger.”

The last thing I am is strong.

“Get some sleep,” I whisper.

“Rhine?”

“What?”

“I told Linden to believe you. I told him it’s true that Housemaster Vaughn is doing awful things downstairs.”

I feel hope. Linden might not have any reason to believe me, but he’ll listen to Cecily. Even if it’s just to humor her so she doesn’t go hysterical on him. “You did?”

“He wouldn’t listen at first,” she says. “It was while you were in the hospital. But I begged him to go and see for himself.”

“Did he?” I ask.

“Yes,” she says. “But—when he came back, he said there was nothing down there. A few of Housemaster Vaughn’s chemicals and things, lots of machines and attendants working on them, but no bodies. No Deirdre. He says you must have been hallucinating, or making it all up.”

Hope swims away, leaving me with less than nothing. “But you saw those things too,” I press. “Did you tell him that?”

Now she’s the one brushing her fingers through my hair, trying to console me. “I only saw what was happening to you,” she says. “I wish I’d seen more. I wish I’d seen Deirdre, or Rose’s domestic, what was her—”

“Lydia,” I say.

“Right. Lydia. I wish I could prove it.” She’s talking to me in that hushed, cooing tone usually reserved for her son. Trying to lull me to sleep, or compliance.

And then I realize why.

“You don’t believe me,” I say.

“Oh, Rhine, Housemaster Vaughn did such terrible things to you. You were so delirious, and so sick. Maybe there’s a chance some of it—”

“It was real,” I say, sitting up. “It was all real.”

She sits upright herself, facing me in the darkness. She’s frowning. “There was nothing down there, Rhine.”

“He hid them, then,” I say. “The bodies. The domestics. If Gabriel were here, he’d tell you the same thing.”

Cecily straightens her posture, hopeful. She wants to believe me. “Did he tell you there were bodies down there?”

“Not exactly,” I say.

“What did he tell you?”

My stomach sinks. I collapse back onto the pillow, defeated. “Not much,” I admit. He was so high on opiates at first, and then it was one problem after the next, really. “He didn’t have a chance.”

Cecily lies beside me, rubs my arm reassuringly. We both go silent. I struggle to cope with the fact that I am the only one who saw what Vaughn kept in the basement. But even worse than that, I want to believe what Linden and Cecily do, that none of it really happened. Maybe it didn’t. Maybe Deirdre really did get sold to another house when I left, and Adair and Lydia too. Maybe they’re comfortable and safe, and I’d conjured Deirdre up to cope with the loneliness as I lay strapped to that bed. She visited me often.

I start to make a list in my head of all the things I know. Vaughn killed Jenna; he admitted as much. Rose’s body was in the basement that day the elevators gave out. I saw her. I recognized her nail polish, her blond hair. There was a tracker in my leg. Deirdre told me about it. Didn’t she? I think of all the attendants who came to work on me while I was in the basement. In my memory they all have the same blank expressions; they’re all voiceless, uncaring. Deirdre was warm. She spoke gently, made me feel safe, which was a bizarre thing in that place.

The list collapses in on itself, words and memories jumbling into a bloody mess. It’s so frustrating the way the pictures keep on changing.

In the end it’s Cecily I reach for. At least I can be certain she exists. Her skin is sweaty and warm as I scrunch up the sleeves of the nightgown she borrowed from me. I worry about how overheated she gets, like there’s a fire inside her. I think she drifted off to sleep and I woke her, because she mumbles something nonsensical before opening her eyes. “You don’t have to believe me,” I tell her. “You just have to believe that Vaughn is capable of those things.”

“I do,” she says. “Linden doesn’t. I think he chooses not to. He’s sensitive, you know?”

She strokes my cheek with the side of her hand—a repetitive, wispy motion. Like little ghost kisses.

“I thought Housemaster Vaughn wanted to do good things and save us all,” she says. “I was wrong. And admitting that meant admitting he won’t find an antidote and none of us has much time. You said you have to find your brother—so you should go do that. And Linden and I have Bowen, and this baby. I want to spend as much time with them as I can. I want to be with them until the end.”

These are all things she wouldn’t have dared to say last year. But now she’s unflinching. Her voice doesn’t even catch when she adds, “If all those things you saw are real, there’s nothing we can do about them. We have our own lives to take care of, and there’s only time to do so much with them.”

What she says is terrible and true. She grabs my hand. We squeeze each other’s fingers, and I wait for her to realize the magnitude of what she’s said. I wait for her to squish up against me and sob. But from the reason in her tone, I sense that those words have been in her for a long time. That while I was away, she had plenty of time to get used to them.

And when the sob does come, several minutes later, it’s mine.

My sister wife has already fallen asleep.

I dream of Linden in the doorway. He looks at me a long while, the green in his eyes changing every second. “The stars do look like a kite,” he admits. “But everything else you’ve said is a lie.”

In the morning I awaken to Cecily jumping from the bed, her feet crashing onto the floorboards like baritone notes, to get to the window. “Quiet,” I tell her, cringing at the sudden light when she yanks the window shade, forcing it to recoil with a slurping noise.

“No, no, no. You have to hide,” she tells me. Panic in her eyes. The sound of an engine purring under the window.

I stagger to my feet, every muscle sore, and walk to the window. And outside is the limo, a figure standing beside it waving us down. Linden said he’d be here to collect Cecily in the morning, but as my grogginess subsides, I realize that Linden isn’t here.

Vaughn is.

3

“STAY HERE,” I say, hurrying to put on a pair of jeans under my nightgown.

“Wait!” Cecily calls after me as I’m running down the stairs.

“Stay!” I tell her.

Outside, the early morning air is cold, and I hug my arms for warmth. Dewy grass clings to my bare feet as I move toward him. He smiles. “Ah, so she awakens,” he says. His voice disrupts the gray sky. A burst of blackbirds rushes past.

I maintain my distance, keep my tone neutral when I ask, “Where’s Linden?”

“Your husband had an early meeting with a potential contractor,” he says. “He sent me for you and Cecily.”

“Sure he did,” I say, bracing one foot behind me to take a step back.

“You’re still angry with me,” he says. “I understand. But, Rhine, darling, you’re such a fascinating creature. You should be flattered; before you came along, I was sure I’d seen everything. I couldn’t help but get carried away.”

Carried away. I laugh humorlessly, a cloud bursting from my open mouth.

“Let’s just be honest with each other. If it weren’t for me, you’d be dead,” he says.

“Thanks to you, I almost was,” I say. “What will you do if I refuse to go along this time? Burn down this house?”

“While I do think a fire would be an improvement, no. The choice is entirely your own,” he says, sounding sincere. “I thought you and I could put this sordid mess behind us. How does resuming first wife status sound?”

I open my mouth, aghast, but no words come. How did he even find me here? The tracker has been removed from my leg. Did Linden really send him here after me? I know he’s angry, but I don’t believe he’d do anything so venomous.

The screen door slams behind me, and then I realize it. Cecily. Vaughn can’t trace my steps anymore, but she is still his property. How does it work? Is there a computer somewhere that spells out our location on a digital map? Or some kind of beeping device that sounds an alarm when we’re nearby, like a metal detector hovering over coins? My parents used to have one of those; it was often how my father found scrap metal to build things with.

She moves to stand beside me, coiling her arm around mine. “She isn’t going back,” she says.

“You don’t want your sister wife to come home?” Vaughn says. “But you’ve been so lonely. So lonely, in fact, that you were sneaking down to visit her every time I left the house.”

She draws a deep breath. She’s scared, though she’s trying not to let on.

“Don’t go with him,” I say into her ear.

The screen door slams again, and I catch a whiff of smoke. Reed has a cigar in his mouth. Grease and brown splotches stain his white shirt. “Nobody was going to invite me to the reunion?” he says to Vaughn. “You can’t have it both ways, Little Brother. If I can’t come onto your property, you can’t come onto mine.”

“I’ve just come to collect something that belongs to me,” Vaughn says. “Put something decent on, Cecily. Run a brush through that hair, and let’s go.” She’s still wearing one of the nightgowns that Linden packed for me, the unbuttoned collar dipping over her shoulder.

“I’ll leave when my husband gets here,” Cecily says. “Not before then.”

“You heard the kid,” Reed says.

Vaughn opens his mouth to say something, but the sound of a baby crying interrupts him. And the words he was going to say turn into a grin. Cecily stiffens.

Vaughn opens the passenger door and says, “Come on out and talk some sense into your keeper.”

Elle, Cecily’s domestic, steps out of the car. She’s holding Bowen to her chest, and his face is red and wet with tears. Cecily reaches for him immediately, but Vaughn steps in her way. “It’s chilly out here, darling,” he says. “And you’re pregnant. You don’t even have the sense to wear a coat. What makes you think you can get by without me to supervise your prenatal care? You’ve already missed your vitamins this morning.”

“He’s right,” Elle says a bit too softly. She’s looking at the ground, and her words sound rehearsed. She’s smaller than Cecily—nine, maybe ten years old, and of all our domestics she’s always been the most timid. I’m sure it was no challenge for Vaughn to intimidate her.

Cecily purses her lips together, composing herself. I think she’s trying not to cry. “You can’t keep my son from me.”

Vaughn laughs, taps her nose the way he did when she was a newlywed, when she adored him because she didn’t know any better. “Of course not,” he says. “You’re the one who’s been away from him.”

She steps past Vaughn, and he grips her forearm when she tries to reach for her son. I see the strain in his arm from the force of holding her. Her jaw swells with spite. He has never grabbed her before; he’s always been able to command her with his serpent’s charm. “Come home, or don’t,” he says. “But know that I won’t allow my grandson to stay here in this cesspool.”

He looks at me and adds, “As always, the invitation is extended. It wouldn’t be home without you.”

“Whose home?” I mutter. I take a step back, into the choking smog of Reed’s cigar. He says nothing, standing on the top porch step. This isn’t his battle.

Cecily looks at me with the same regret as on the day I told her our father-in-law was responsible for Jenna’s death, when snow was falling between us. And my heart breaks the same way it did then. “I have to go,” she says.

“I know,” I tell her, because I realize it too. She has Bowen and an unborn child to care for, and a husband to love. I have my brother and Gabriel to find. Cecily and I can’t keep each other safe. We have to let go.

Vaughn releases her, and she comes at me, hugging me with so much force that I stumble. I wrap my arms around her. “Take care,” she murmurs into my ear. “Be brave, okay?”

“You too,” I say.

She lets go of me when Bowen’s cries jump up a few octaves. Vaughn escorts her to the car and waits until she has climbed inside, before instructing Elle to hand her the baby.

Cecily clings to her son, but watches me over his wispy curls. Her lower eyelids have gone pink, a wavering line of tears tracing them. We know how unlikely it is that we’ll ever see each other again. If Linden had come to collect her, at least we’d have had time for a real good-bye.

Vaughn climbs in beside her and closes the door, and I’m left staring at my own reflection in the darkened windows. Until even that is gone.

Reed steps beside me, and together we watch the limo get swallowed by the horizon. He offers me a puff of his cigar, but I shake my head, letting the numbness take over my head, welcoming the pain into my bones. Waiting for this sadness to disappear like both of my sister wives.

“Don’t feel bad, doll,” Reed says. “My mother never cared for Vaughn either. Though, bless her soul, she did try.” He claps my shoulder. “Better get washed up. There’s work to do.”

The water trickles from the showerhead; it runs bleary and chunked with rust. But it’s not very much worse than what I was used to in Manhattan, and I’m able to get reasonably clean by not standing directly under it and splashing myself when it’s at its clearest. I take extra care with the gash that runs along my inner thigh, the skin pinched together with stitches.

When I go through the suitcase Linden packed, I find that he left a roll of gauze and a bottle of antiseptic in one of the inner pouches by my toothbrush, where I’d be sure to see them. He was still thinking of me, caring for me in that passive way of his. Everything is neatly folded too. A lesser husband would be angry after what I put him through, would hope the wound became infected and the entire leg fell off.

I dress the wound, and try to roll up the rest of the gauze as neatly as I found it, but I can’t duplicate Linden’s meticulousness.

Remembering what Reed said last night about the machines, I tie my hair back with one of the many rubber bands hanging on the doorknob. Rubber bands on doorknobs, and bolts and rusty nails in glass jars, stacked into pyramids in corners. The entire house is a sort of machine, as though gears are turning between the walls.

The downstairs hallway smells like fried lard, becoming more pungent when I reach the kitchen. “Hungry?” Reed asks. I shake my head.

“Didn’t think so,” he says, pouring grease from a frying pan into an old can. “You seem birdlike. Even your hair is like a nest.”

Maybe I should take offense, but I don’t mind this image of me he’s painting. It makes me feel wild, brave.

“Bet you never eat,” he says. “Bet you drink up the oxygen like it’s butter. Bet you can go for days on nothing but thoughts.”

That gets a smile out of me. I can see why Vaughn wouldn’t like his brother, and why Linden would.

“So,” he says, turning to face me. “My nephew tells me you’re still recovering. But you look recovered to me.”

Linden did say his uncle wouldn’t ask many questions, and he hasn’t. But he has a clever way of getting answers with carefully worded statements.

“I am,” I say. “Mostly. I’ll only be a day or two, and I can be useful in the meantime. I know how to keep a house running. How to fix things.”

“Fixing things is good,” he says, walking past me. I follow him down the hallway, out the front door, into the breezy May air. The grass and the bright weeds of flowers sway on the wind like the hologram that came from the keyboard as Cecily played. A stop-motion drawing in colored pencil, unreal.

It’s gotten warmer since this morning, and there’s the almost plastic smell of grass. I think of Gabriel, how this time last year he brought me tea in the library and read over my shoulder. He pointed to the sketches of boats on the page of the history book, and I thought that it would be nice for us to sail away, the water dividing endlessly in the sunlight. Breaking in half and then breaking in half again.

I push back my worries. I’ll come to find him soon; that’s all I can hope for.

Reed shows me to the shed beside his house, which might have once been a barn. It’s enormous enough. “Even things that aren’t broken can be fixed,” he says. The darkness smells like mold and metal. “Everything can become something it’s not.”

He looks at me, eyebrows up, like it’s my turn to say something. When I remain quiet, it seems to disappoint him. His fingers flutter over his head as he presses forward.

It’s hard to see. The only light comes through gaps in the wooden planks that make up the walls.

Then Reed pushes on a far wall, and it swings open. It’s a giant door, and at once the place is flooded with sunlight. Awkward shapes around me become leather straps, guns mounted up by nails, car parts hung like carrion in a butcher shop. The floor is nothing but packed dirt, and there’s a long worktable covered with so many odd things, I can’t make sense of them.

“Never seen anything like it, I bet,” Reed says, sounding pleased with himself. I get the sense that he takes pride in being perceived as mad. But he doesn’t seem mad to me. He seems curious. Where his brother unravels human beings, weighing their organs in his bare palms, prying back eyelids, drawing blood, Reed unravels things. He showed more care with that engine on his table last night, more respect for its life, than Vaughn ever showed with me.

“My father liked to make things,” I say. “And fix things. But woodworking, mostly.”

I don’t know what’s making me talk so much. In the almost year I spent at the mansion, I don’t think I revealed so much truth about myself as I have this morning.

I’m homesick, I suppose, and talking to a total stranger is my way of dealing with it.

Reed looks at me, and I catch the green in his eyes. He’s like his brother there. They both have that distance, living in the world their thoughts create. He stares at me a long time and then says, “Say ‘ridiculous.’”

“What?”

“The word ‘ridiculous,’” he insists. “Say it.”

“Ridiculous,” I say.

“An absolute ghost,” he says, shaking his head and dropping into a seat at his worktable. It’s really an old picnic table with attached benches. “You look just like my nephew’s first wife. You even have her voice, and ‘ridiculous’ was her favorite word. Everything was ridiculous. The virus. The attempts to cure it. My brother.”

“Your brother is ridiculous,” I agree.

“I’m going to call you Rose,” he says with resolution, picking up a screwdriver and working the back off an old clock.

“Please don’t,” I say. “I knew Rose. I was there when she died. I’d find it creepy.”

“Life is creepy,” Reed says. “Kids rotting from the inside out at age twenty is creepy.”

“Even so, my name is Rhine,” I say.

He nods for me to sit across the table from him, and I do, avoiding a gray puddle of something on the bench. “What kind of name is ‘Rhine,’ anyway?” he asks.

“It’s a river,” I say. I upturn a bolt and try to spin it like a top. My father used to make them for me and my brother. We’d spin them at the top of the stairs, and crush our shoulders together as we watched them jump down one step to the next. His always got there first, or else mine slipped through the banister and fell away. “Or it was a river, a long time ago. It ran from the Netherlands to Switzerland.”

“Then I’m sure it still does run there,” Reed says, watching the bolt spin away from my fingers and promptly collapse. “The world is still out there. They just want you to think it’s gone.”

Okay, maybe he is a little bit mad. But I don’t mind. Linden is right. Reed doesn’t ask many questions. He spends the rest of the morning keeping me busy with menial tasks, never telling me what it is I’m doing. As near as I can tell, I’m disassembling an old clock to make a new one. He checks on me sometimes, but spends most of the time outside, lying flat under an old car, or climbing inside to start its engine, which only splutters and creates black clouds through the tailpipe. He hides away in an even bigger shed farther back, higher than the house and more makeshift, as though he built it as an afterthought, to cover what’s inside.

But I don’t ask about that, either.

4

IT’S LIKE THAT for the rest of the day, and the next day, and the next. I don’t ask questions, and neither does Reed. He places tasks before me, and I do them. One piece at a time. Never knowing what I’m assembling. I watch him, too. He spends a lot of time under cars or in that lumbering shed with the door closed.

I never have much of an appetite, and the safest things to eat in his kitchen are the apples, anyway, being that they’re the only things I recognize. They’re not the ultrabright green and red fruit I got used to in the mansion. They’re speckled, flawed, and mealy, the way I grew up thinking they should be. I’m still not sure which way is more natural.

On my fourth morning, when I climb out of bed, I notice that the dizziness and the flecks of light are gone. The pain in my thigh has dulled, and the stitches have started to disintegrate. “I think I’ll leave tomorrow,” I tell Reed while we’re sitting on opposite sides of his worktable. “I’m feeling much better.”

He’s taking a magnifying glass to some heap of machinery—a motor, I think. “Did my nephew arrange for transportation?” he asks.

“No,” I say, tracing my finger around the rim of a mason jar filled with screws and grime. “That wasn’t part of the agreement.”

“So there was an agreement,” Reed says. “Doesn’t seem like it. Seems like you’re just making it up as you go.”

Story of my life. There’s no real way to counter that, so I just shrug. “I’ll be all right,” I say. “He knows there’s no reason to worry about me.”

Reed glances at me for a moment, his forehead creased, eyebrows raised, before he returns to his task. “The fact that you’re here says he’s worried about you,” he says. “Doesn’t want you anywhere near his father, that much is clear.”

“Vaughn and I don’t exactly get along,” I say.

“Let me guess,” Reed says. “He tried to pluck out your eyes for science.” He says that last word, “science,” with such exaggerated passion that I laugh.

“Close,” I say.

He stops working, leans forward, and stares at me so intently that I can’t help but look back at him. “It was no car accident, was it?” he says.

“What do you keep in that shed?” I counter. Since we’re asking questions.

“An airplane,” he says. “Bet you thought they were extinct.”

It’s true there aren’t many airplanes. Most people wouldn’t be able to afford traveling that way, and most cargo is transported by truck. But the president and select wealthy families have them for business or leisure. Vaughn, for instance, could afford one if he wanted. But my guess is that what Reed calls an airplane is a patchwork of different parts, and not something I’d want to board.

I look at the table. He answered my question; now he’s waiting for me to answer his.

“Vaughn was using me to find an antidote,” I say. “Something about my eyes being like a mosaic, or something. I don’t know. It’s hard to follow him.” And at the time, I had so many drugs running through me that I thought the ceiling tiles were singing to me. Those days were so vivid at the time, but now, looking back, the memory is a shadow at the end of a long corridor. I can’t remember much of anything.

“Doesn’t sound like something my nephew would allow,” Reed says. “Don’t get me wrong, the poor boy is as oblivious as a rabbit on a lion reserve, but still.”

Animal reserves are a thing of the past, but somehow this comparison feels right.

“He didn’t know,” I say. “And when I told him, he didn’t really believe it was as bad as it was. He still won’t. So we’ve decided it’s best to”—I pause, looking for the right words—“part ways. He and Cecily have the new baby coming, and I need to find my brother.” And Gabriel, but that would require even more explaining, and I’m already starting to feel exhausted and achy just thinking about what’s been said so far.

The dull aching becomes a stab of pain in my temple when Reed asks, “Then, why, doll, are you still wearing his ring?”

My wedding ring. Etched with fictional flowers that don’t begin and don’t end. More than once I’ve thought about cutting into it with something sharp. Making a line, severing the vines just so they stop somewhere.

“Can I see your plane?” I ask. “Does it fly?”

He laughs. It’s nothing like Vaughn’s laugh. There’s warmth in it. “You want to see the plane?”

“Sure,” I say. “Why not?”

“No reason not to, I suppose,” he says. “It’s just that no one’s ever asked before.”

“You have an airplane in your shed, and no one has ever asked to see it?” I say.

“Most people don’t know it’s there,” he says. “But I like you, not-Rose. So maybe tomorrow. For now, we have other things to do.”

That night I lie in Reed’s yard. It stretches on farther than I can see, empty, aside from the tall grass and the bursts of wildflowers. I lie on the dirt and think, There is where the orange grove would be. And over there, the golf course, with its spinning windmill, its lighthouse gleaming. And farther down would be the stables, abandoned now, where Rose and Linden used to keep their horses. And here, where I’m lying, would be the swimming pool. I could coast on an inflatable raft as imaginary guppies flicked their bodies around me in glimmers of color.

I thought I’d left that place behind me. But it keeps rebuilding itself in my mind.

Something rustles nearby and I turn my head, watching the grass move. I get the terrible sense that it’s trying to warn me.

I sit up and hold my breath, trying to listen. But a gust of wind is rolling through. I think it’s saying my name. No, that voice didn’t belong to the wind, though it would make more sense than the truth.

“Rhine?”

I lean back on my arms, tilt my head all the way to see the figure standing behind me.

“Hi,” I say.

The moon is full and beaming like a halo behind his head. His curls are his dark crown. He could be a sort of prince.

“Hi,” Linden says. “Can I sit?”

I collapse onto my back, liking the way the cold earth feels against my skull. I nod.

He sits next to me, careful to avoid my hair that’s splayed around my head like blood. A bullet to the forehead, boom, blond waves everywhere.

“Didn’t think you were coming back,” I say, focusing on the kite in the stars. I look for other kites, or people to fly them.

Linden lies beside me. All I can think is that he’s going to get grass stains on his white shirt. He’s going to dirty that lovely hair. I feel like he’s trying to prove a point that he can be like me—not so neat and perfect.

“I didn’t send my father, the other day,” he says. “I didn’t know he was going to do that.”

What he doesn’t say is that his father probably tracked my whereabouts using whatever device he implanted in Cecily. Linden saw for himself the one that had been implanted in me.

“Thought you said you knew him so well,” I mumble. Without looking back, I can feel his stare.

“He was trying to spare me,” Linden says. “He knew how difficult it would be for me to see you.”

“So you were spared,” I say. “Why did you come back?”

“My uncle called me this afternoon,” he says.

“I didn’t know you even had a phone,” I say. Somehow this feels like a violation, a reminder that while Linden treated me as an equal during our marriage, that was only part of the illusion. I was always a prisoner.

“He told me you were leaving,” Linden says. “He said you just planned to walk off and leave everything to chance.”

“Something like that,” I say.

“That’s not much of a plan,” he says. “What are you going to do for money? Transportation? Food? Where will you sleep?”

I shake my head. “It doesn’t matter.”

“Of course it matters.”

“This is why Reed was stalling, isn’t it? He wanted to talk to you before I left.” I suppress a cry of frustration. “Please just let this be my problem,” I say. “Not yours.”

He’s silent after that. The silence adds a foreign element to the air, polluting the moonlight, making my throat tight, the crickets extra loud. Planets are leaning in to listen. And finally I can’t take it anymore. “Just say it,” I tell him.

“Say what?”

“Whatever it is you want to say to me. There’s something ugly in there you’ve been wanting to let out. I can tell.”

“It’s not ugly,” he says gently. “Or angry at all, really. It’s more of a question.”

I prop myself on one elbow to look at him, and he does the same. There’s no hostility in his eyes. There’s no kindness, either. There’s nothing but green. “That night, at the New Year’s party, you said you loved me. Did you mean that?”

I stare at him a long time. Until his face disappears, and he’s just a shadow.

“I don’t know,” I tell him. “If I did, it wasn’t enough to make me stay.”

He nods. Then he gets up, dusts the backs of his legs, and offers his hand to me. I let him pull me to my feet.

“Don’t leave tomorrow,” he says. “Please. Give me a chance to figure something out. If I just let you go, Cecily will be livid.”

“She’ll be okay,” I say. “You don’t owe me anything.”

“Then think of it as doing me a favor,” he says. “I’d like for Cecily to not be angry with me.”

I hesitate. “How long?”

“A couple of days, maybe less.”

“All right,” I say. “A couple of days. Maybe less.”

His lips waver, and I think he’s going to smile, but he doesn’t. The last time I saw him, he was brimming with words and thoughts, anger and intensity. I could feel them humming inside him. But now they’re all gone. I wonder where he put them. I wonder if he shouted them into the orange grove with the supposed ashes of his dead wife and child. When he opens his mouth, all he says is, “If you’re going to be out here, you should really wear a sweater. I packed one for you.”

Then he turns to leave. The limo is idling in the distance.

“It wasn’t all a lie, Linden,” I burst out when he’s a few yards away. My voice is weak, getting smaller with each word. “Not everything. Not all of it.”

He climbs into the backseat, giving no indication that he believes me.

5

REED SITS across the kitchen table, watching me as I turn the apple in my fingers. Maybe he’s right about my never needing to eat. I can’t remember the last time I had a real appetite. Even the delicacies served to me on the wives’ floor wouldn’t appeal to me right now.

I keep my eyes down. I don’t want Reed to see my defeat. I don’t want him to see that Vaughn has had a victory over me, because almost all of my misfortunes can be traced to that man. Being separated from my brother. Losing Jenna. Watching Cecily go with tears in her eyes. Leaving Gabriel to fear the worst. Linden’s coldness toward me. I keep staggering forward because I have to, but what Linden said last night is true: It’s not much of a plan.

“Are you going to eat that, or submit it for fingerprint analysis?” Reed says.

I set the apple down neatly, and tuck my hands under the table.

He tilts his head, watching me. He’s eating some sort of deep-fried stew. The smell is repulsive; some of it drips onto his plaid shirt.

“Okay, then,” he says. “No food today either. So what will sustain you?”

“Oxygen,” I say softly.

“You need to spice it up with something,” he says. This is his way of making conversation. I think he feels sorry for me.

“A question, then,” I say.

He sets his spoon into the bowl with authority. “All right. Go for it.”

I look aside, thinking of how I want to word this. “You and Vaughn don’t seem anything alike,” I begin. “I guess my question is—was he always this way? You said your mother didn’t really care for him.”

Reed laughs gruffly. “He was quiet all the time. I don’t mean like he was being polite or solemn. I mean like he was planning something.”

“He’s still like that,” I say. I try to imagine Vaughn as a child or even as a young man, but I can’t. All I see is a version of a young Linden with blackness where his eyes should be.

“But he didn’t have much purpose until his boy died,” Reed says. “That’s when he reprogrammed the elevators so that only he could access the basement. I never knew what was going on down there.”

“Did he used to let you visit?” I ask, thinking of what Reed said a few days ago about Vaughn not allowing Reed onto his property.

“I used to live there,” Reed says. “When our parents died, they left that house to both of us. Our father was an architect, and it was an old boarding school he’d reconstructed. That’s why it’s so enormous. You’d think, with all that space, there’d be room for both of us. But we seemed to get in each other’s way. We both like things just so.”

“Linden’s grandfather was an architect,” I say quietly, more to myself than to Reed. It makes me happy to know Linden inherited that brilliance. It skipped his father and buried itself in him, like it knew he would do better things with it.

“Linden takes after him in a lot of ways,” Reed agrees. “Vaughn hates when I point that out. He likes to pretend he’s the only family that boy’s got. Won’t even talk about Linden’s mother, or Linden’s brother that died before he was born. It’s one of the things we butted heads about. My brother and I were already walking a fine line with each other, but I suppose the last straw was when Linden fell ill.”

I raise my head at that. Linden told me about a time when he was very sick as a child. He could hear his father’s voice calling him back to consciousness, but he was too scared to answer. He’d made the decision to let go, but he survived anyway.

Reed stares at something over my shoulder, his pupils turning to pinpricks. “That poor boy,” he says distantly. “I really thought it was the end of him.”

“What was it?” I ask, and he snaps back to attention and looks at me. “What made him so sick?”

“I can tell you what Vaughn said, or I can tell you what I think,” he says.

I press my eyebrows together. “You think Vaughn was responsible?”

“Not on purpose,” Reed says. “I don’t think he meant to harm him. But I think he was running some experiment that went haywire. I called him out on it, and he asked me to leave.”

“So you did?” I ask.

“I did,” he says. “I’m better off with my own place anyway. I would have liked to take my nephew with me, but Vaughn would have had my head for it. There’s nowhere I could take that boy where Vaughn wouldn’t have found him.”

“I know the feeling,” I mumble.

“Look at that,” Reed says. He slaps his palms on the table, rattling the bowl, startling me. “You asked for an answer to one question, and you got an entire story. Feeling sustained yet?”

In answer I take a bite from the apple.

“Finish your breakfast and then tie that hair back. I have a new project for you.”

“New project?” I say before taking another bite.

“A cleaning project,” he says. He drops his bowl into the sink and then winks at me. “I think you have a knack for making things shine.”

Once I finish the apple and throw the core into the compost pile that Reed started just outside the kitchen window, and swat away a good deal of flies, Reed leads me past the usual shed and keeps going toward the bigger one.

“What I’m about to show you is top secret stuff,” he says. I can’t tell whether he’s kidding. “I wouldn’t want anyone coming out here chopping it up for parts.”

He fiddles around with a padlock, somehow coaxing it apart without a key. Then he pushes the door open, moves aside, and makes a flourishing gesture with his arm for me to enter first.

It’s dark until he flips a switch, and tiny bulbs strung along the ceiling and walls illuminate the space.

“What do you think, doll?” Reed says.

“It’s … a plane. In your shed.” I can’t hide my astonishment. He told me it would be here, and here it is, yet it still surprises me. It’s rusty and mismatched, but it has a body and wings, and it takes up almost the entirety of the shed. “How did you get it in here?” I ask.

“Didn’t,” he says. “Most of it was already here. I figure it probably crash-landed forty, fifty years ago and was abandoned. So I decided to fix it up, see if I could make it fly. Of course the weather proved to make things difficult, so I built this shed over it.”

The whole thing sounds too absurd for him to have made it up. “How will you get it out?” I say. “How will you even start it without being poisoned by the fumes?”

“Haven’t gotten to that part yet,” he says. “But no matter; she’s not ready to fly.”

I stare at it, and for some reason my shoulders shake and I start to laugh. It’s the first real laugh I’ve felt in days. Or weeks. Or months, maybe. Reed is either a genius or completely mad, or both. But if he’s mad, then I am too, because I love this airplane. I’ve never seen one up close before, and the stories I’ve heard never prepared me for the power such a magnificent thing implies. I want to climb inside of it. I want it to carry me up, the grass getting greener and greener the farther away it becomes.

Reed is grinning when he tugs the handle of the curved door. It looks like it once belonged to a car and was melted into shape. With a horrible rusty noise, it opens from the top, like a curled finger rising to point at me.

The door opens to a small cockpit. There are monitors and buttons and what appear to be two half-circle steering wheels. “The supply room’s in the passenger cabin,” Reed says, pointing me to a curtain that serves as a door.

The passenger cabin is all beige and red, like a mouth. It seems almost human. When I was bedridden in the mansion, Linden read a story to me that was about a scientist named Frankenstein who created a man from the body parts of the dead. Somehow Frankenstein gave this creation a pulse and made it breathe. I imagine it must have looked like this odd assemblage of pieces.

The plane is a lot bigger than it looks from the outside. The ceiling is high enough that Reed, who’s taller than me, can nearly stand up straight. There’s some room to walk around. The seats are red, mounted to the wall. There are four of them, in pairs of two, facing each other. The carpet is beige and stained, like the walls.

What Reed calls a supply room is actually a closet. Opening its door reduces the passenger cabin by half. “Needs to be organized,” Reed says, standing at the curtain that separates the cockpit from the passenger cabin. He watches as I open one of the cabinets. Shoe boxes tumble out at me and spill their contents onto my shoes. “I was thinking that’d be your job.”

It’s easy, repetitive work. Sorting medical equipment apart from the dehydrated snacks and labeling their boxes. Reed works on the outside of the plane. I hear him banging parts into place and smoothing them down, trying to blend all the pieces together. He says he’s going to paint it when he’s done. He says it’ll be beautiful. I think it already is.

I open another box, and it’s full of cloth handkerchiefs. I recognize them immediately. They’re exactly like the ones at the mansion: plain white, with a single red sharp-leafed flower embroidered onto them. Gabriel gave me a handkerchief with this pattern, and I kept it for the remainder of my time at the mansion. The same flower that marks the iron gate.

“Oh, those?” Reed says when I ask him about them. He doesn’t look away from his work. He’s sitting on one of the wings, pressing down a sheet of copper and using a screwdriver to mark where the screws will go. “I thought they’d make good bandages; put them with the first aid stuff.”

“Where did they come from?” I ask.

“They used to belong to the boarding school,” he says. “A ton of things were left behind when my parents bought the building—handkerchiefs, blankets, things like that.”

“But what kind of flower is it?” I say.

“It’s a lotus,” he says. “Doesn’t look exactly like one, if you ask me, but that’s the only logical thing it could be. The school was called the Charles Lotus Academy for Girls.”

“Charles Lotus? As in, his name was Lotus?”

“Yep. Now get back to work making things sparkle. I’m not letting you live here eating up all the apples and oxygen for free, you know.”

The rest of the day is a malaise of chores. I pack the handkerchiefs away and bury them at the bottom of all the medical supplies. I don’t want to ever see them again. It’s my fault for hoping they symbolized something important. For believing anything that comes from the mansion could mean anything good.

I take a shower and go to bed early. The sky is still pink, undercooked. I bury myself beneath the blanket. It isn’t very thick; I shiver most nights, but right now the blanket feels like the heaviest thing in the world. It comforts me. I don’t just want to sleep; I want to be crushed down until I disappear.

In the morning there are voices. Something hissing and spitting on the griddle. Footsteps are pounding up the steps, and a voice calls after them, “Wait!” but the footsteps don’t comply. My door is pushed open, and there’s Cecily. The sunlight touches every part of her, making her into an overexposed photograph. Her smile floats ahead of her, a double bright line. “Surprise,” she says.

I sit up, trying to force consciousness back into my brain. “What are you—How did you get here?”