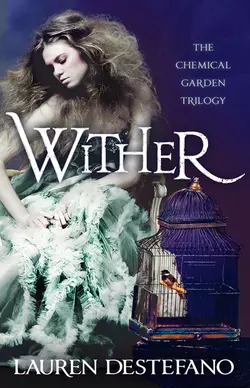

Wither

Lauren DeStefano

A stunning debut YA novel, destined to blow the dystopian genre wide open – The Handmaid’s Tale for a new generation.Sixteen-year-old Rhine Ellery has only four years left to live when she is kidnapped by the Gatherers and forced into a polygamous marriage. Now she has one purpose: to escape, find her twin brother, and go home – before her time runs out forever.What if you knew you exactly when you would die?In our brave new future, DNA engineering has resulted in a terrible genetic flaw. Women die at the age of 20, men at 25. Young girls are being abducted and forced to breed in a desperate attempt to keep humanity ahead of the disease that threatens to eradicate it.16-year-old Rhine Ellery is kidnapped and sold as a bride to Linden, a rich young man with a dying wife. Even though he is kind to her, Rhine is desperate to escape her gilded cage – and Linden’s cruel father. With the help of Gabriel, a servant she is growing dangerously attracted to, Rhine attempts to break free, in what little time she has left.

Dedication

Epigraph

Contents

Cover (#ulink_bec8a57d-2033-55ca-9139-e455448eb74d)

Title Page (#uec5c47a9-560e-5aba-be7a-61cd6c4f4432)

Dedication

Epigraph

1

I WAIT. They keep us in the dark for so…

2

FOR MALES twenty-five is the fatal age. For women it’s…

3

IT’S NOT GABRIEL who wakes me in the morning, but…

4

IT’S MY TURN to keep watch. We’ve locked the doors…

5

WHEN THE EVENING is at last through, I languish on…

6

“I WANT TO PLAY a game,” Cecily says.

7

I HOLD MY BREATH as they pass. Eternity is the…

8

THE ATTENDANTS arrive in abundance. All of them rushing into…

9

LINDEN is so delighted about the pregnancy, and the mood…

10

IT SEEMS THAT leaves are always bursting with new colors.

11

THE HOUSE doesn’t blow away. Aside from a few broken…

12

THE AIR IS STILL. It’s quiet. I can breathe without…

13

LINDEN SEEMS to have no idea that I sustained these…

14

ALL NIGHT I dream of rivers, and beneath the water,…

15

WHEN CECILY finishes playing her song, and the illusion shrinks…

16

I DON’T SEE GABRIEL the next day. My breakfast is…

17

I’M SICK for the rest of the afternoon. Jenna holds…

18

LINDEN SAYS, “You and Jenna get along well, don’t you?”

19

I WORRY for the rest of the evening. Deirdre tries…

20

WE WAIT, and we wait. I want to look away,…

21

ON THE MORNING of the winter solstice, Jenna manages to…

22

THE BABY will not stop crying. His face is bright…

23

JENNA WAS RIGHT. She leaves before I do. We lose…

24

WE RETURN from the New Year’s party in the early…

25

IN THE MONTH before my escape, I spend all of…

26

I TAKE the elevator to the ground floor and cross…

27

WE RUN for what feels like all night. It feels…

Fever

The First Bride

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

we lose sense of our eyelids. We sleep huddled together like rats, staring out, and dream of our bodies swaying.

I know when one of the girls reaches a wall. She begins to pound and scream—there’s metal in the sound—but none of us help her. We’ve gone too long without speaking, and all we do is bury ourselves more into the dark.

The doors open.

The light is frightening. It’s the light of the world through the birth canal, and at once the blinding tunnel that comes with death. I recoil into the blankets with the other girls in horror, not wanting to begin or end.

We stumble when they let us out; we’ve forgotten how to use our legs. How long has it been—days? Hours? The big open sky waits in its usual place.

I stand in line with the other girls, and men in gray coats study us.

I’ve heard of this happening. Where I come from, girls have been disappearing for a long time. They disappear from their beds or from the side of the road. It happened to a girl in my neighborhood. Her whole family disappeared after that, moved away, either to find her or because they knew she would never be returned.

Now it’s my turn. I know girls disappear, but any number of things could come after that. Will I become a murdered reject? Sold into prostitution? These things have happened. There’s only one other option. I could become a bride. I’ve seen them on television, reluctant yet beautiful teenage brides, on the arm of a wealthy man who is approaching the lethal age of twenty-five.

The other girls never make it to the television screen. Girls who don’t pass their inspection are shipped to a brothel in the scarlet districts. Some we have found murdered on the sides of roads, rotting, staring into the searing sun because the Gatherers couldn’t be bothered to deal with them. Some girls disappear forever, and all their families can do is wonder.

The girls are taken as young as thirteen, when their bodies are mature enough to bear children, and the virus claims every female of our generation by twenty.

Our hips are measured to determine strength, our lips pried apart so the men can judge our health by our teeth. One of the girls vomits. She may be the girl who screamed. She wipes her mouth, trembling, terrified. I stand firm, determined to be anonymous, unhelpful.

I feel too alive in this row of moribund girls with their eyes half open. I sense that their hearts are barely beating, while mine pounds in my chest. After so much time spent riding in the darkness of the truck, we have all fused together. We are one nameless thing sharing this strange hell. I do not want to stand out. I do not want to stand out.

But it doesn’t matter. Someone has noticed me. A man paces before the line of us. He allows us to be prodded by the men in gray coats who examine us. He seems thoughtful and pleased.

His eyes, green, like two exclamation marks, meet mine. He smiles. There’s a flash of gold in his teeth, indicating wealth. This is unusual, because he’s too young to be losing his teeth. He keeps walking, and I stare at my shoes. Stupid! I should never have looked up. The strange color of my eyes is the first thing anyone ever notices.

He says something to the men in gray coats. They look at all of us, and then they seem to be in agreement. The man with gold teeth smiles in my direction again, and then he’s taken to another car that shoots up bits of gravel as it backs onto the road and drives away.

The vomit girl is taken back to the truck, and a dozen other girls with her; a man in a gray coat follows them in. There are three of us left, the gap of the other girls still between us. The men speak to one another again, and then to us. “Go,” they say, and we oblige. There’s nowhere to go but the back of an open limousine parked on the gravel. We’re off the road somewhere, not far from the highway. I can hear the faraway sounds of traffic. I can see the evening city lights beginning to appear in the distant purple haze. It’s nowhere I recognize; a road this desolate is far from the crowded streets back home.

Go. The two other chosen girls move before me, and I’m the last to get into the limousine. There’s a tinted glass window that separates us from the driver. Just before someone shuts the door, I hear something inside the van where the remaining girls were herded.

It’s the first of what I know will be a dozen more gunshots.

I awake in a satin bed, nauseous and pulsating with sweat. My first conscious movement is to push myself to the edge of the mattress, where I lean over and vomit onto the lush red carpet. I’m still spitting and gagging when someone begins cleaning up the mess with a dishrag.

“Everyone handles the sleep gas differently,” he says softly.

“Sleep gas?” I splutter, and before I can wipe my mouth on my lacy white sleeve, he hands me a cloth napkin—also lush red.

“It comes out through the vents in the limo,” he says. “It’s so you won’t know where you’re going.”

I remember the glass window separating us from the front of the car. Airtight, I assume. Vaguely I remember the whooshing of air coming through vents in the walls.

“One of the other girls,” the boy says as he sprays white foam onto the spot where I vomited, “she almost threw herself out the bedroom window, she was so disoriented. The window’s locked, of course. Shatterproof.” Despite the awful things he’s saying, his voice is low, possibly even sympathetic.

I look over my shoulder at the window. Closed tight. The world is bright green and blue beyond it, brighter than my home, where there’s only dirt and the remnants of my mother’s garden that I’ve failed to revive.

Somewhere down the hall a woman screams. The boy tenses for a moment. Then he resumes scrubbing away the foam.

“I can help,” I offer. A moment ago I didn’t feel guilty about ruining anything in this place; I know I’m here against my will. But I also know this boy isn’t to blame. He can’t be one of the Gatherers in gray who brought me here. Maybe he was also brought here against his will. I haven’t heard of teenage boys disappearing, but up until fifty years ago, when the virus was discovered, girls were also safe. Everyone was safe.

“No need. It’s all done,” he says. And when he moves the rag away, there’s not so much as a stain. He pulls a handle out of the wall, and a chute opens; he tosses the rags into it, lets go, and the chute clamps shut. He tucks the can of white foam into his apron pocket and returns to what he was doing. He picks up a silver tray from where he’d placed it on the floor, and brings it to my night table. “If you’re feeling better, there’s some lunch for you. Nothing that will make you fall asleep again, I promise.” He looks like he might smile. Just almost. But he maintains a concentrated gaze as he lifts a metal lid off a bowl of soup and another off a small plate of steaming vegetables and mashed potatoes cradling a lake of gravy. I’ve been stolen, drugged, locked away in this place, yet I’m being served a gourmet meal. The sentiment is so vile I could almost throw up again.

“That other girl—the one who tried to throw herself out the window—what happened to her?” I ask. I don’t dare ask about the woman screaming down the hall. I don’t want to know about her.

“She’s calmed down some.”

“And the other girl?”

“She woke up this morning. I think the House Governor took her to tour the gardens.”

House Governor. I remember my despair and crash against the pillows. House Governors own mansions. They purchase brides from Gatherers, who patrol the streets looking for ideal candidates to kidnap. The merciful ones will sell the rejects into prostitution, but the ones I encountered herded them into the van and shot them all. I heard that first gunshot over and over in my medicated dreams.

“How long have I been here?” I say.

“Two days,” the boy says. He hands me a steaming cup, and I’m about to refuse it when I see the tea bag string dangling over the side, smell the spices. Tea. My brother, Rowan, and I had it with our breakfast each morning, and with dinner each night. The smell is like home. My mother would hum as she waited by the stove for the water to boil.

Blearily I sit up and take the tea. I hold it near my face and breathe the steam in through my nose. It’s all I can do not to burst into tears. The boy must sense that the full impact of what has happened is reaching me. He must sense that I’m on the verge of doing something dramatic like crying or trying to fling myself out the window like that other girl, because he’s already moving for the door. Quietly, without looking back, he leaves me to my grief. But instead of tears, when I press my face against the pillow, a horrible, primal scream comes out of me. It’s unlike anything I thought myself capable of. Rage, unlike anything I’ve ever known.

women it’s twenty. We are all dropping like flies.

Seventy years ago science perfected the art of children. There were complete cures for an epidemic known as cancer, a disease that could affect any part of the body and that used to claim millions of lives. Immune system boosts given to the new-generation children eradicated allergies and seasonal ailments, and even protected against sexually contracted viruses. Flawed natural children ceased to be conceived in favor of this new technology. A generation of perfectly engineered embryos assured a healthy, successful population. Most of that generation is still alive, approaching old age gracefully. They are the fearless first generation, practically immortal.

No one could ever have anticipated the horrible aftermath of such a sturdy generation of children. While the first generation did, and still does, thrive, something went wrong with their children, and their children’s children. We, the new generations, are born healthy and strong, perhaps healthier than our parents, but our life span stops at twenty-five for males and twenty for females. For fifty years the world has been in a panic as its children die. The wealthier households refuse to accept defeat. Gatherers make a living collecting potential brides and selling them off to breed new children. The children born into these marriages are experiments. At least that’s what my brother says, and always with disgust in his voice. There was a time when he wanted to learn more about the virus that’s killing us; he would pester our parents with questions nobody could answer. But our parents’ death broke his sense of wonder. My left-brained brother, who once had dreams of saving the world, now laughs at anyone who tries.

But neither of us ever knew for certain what happens after the initial gathering.

Now, it seems, I will find out.

For hours I pace the bedroom in this lacy nightgown. The room is fully furnished, as though it’s been waiting for my arrival. There’s a walk-in closet full of clothes, but I’m only in there long enough to check for an attic door, like my parents’ closet has, though there isn’t one. The dark, polished wood of the dresser matches the dressing table and ottoman; on the wall are generic paintings—a sunset, a beachside picnic. The wallpaper is made up of vertical vines budding roses, and they remind me of the bars of a prison cell. I avoid my reflection in the dressing table mirror, afraid I’ll lose my mind if I see myself in this place.

I try opening the window, but when that proves futile, I take in the view. The sun is just beginning to set in yellows and pinks, and there’s a myriad of flowers in the garden. There are trickling fountains. The grass is mowed into strips of green and deeper green. Closer to the house a hedge sections off an area with an inground pool, unnaturally cerulean. This, I think, is the botanical heaven my mother imagined when she planted lilies in the yard. They would grow healthy and vibrant, thriving despite the wasteland of dirt and dust. The only time flowers bloomed in our neighborhood was when she was alive. Other than my mother’s flowers, there are those wilting carnations that shopkeepers sell in the city, dyed pink and red for Valentine’s Day, along with red roses that always look rubbery or parched in the windows. They, like humanity, are chemical replicas of what they should be.

The boy who brought my lunch mentioned that one of the other girls was taking a walk in the garden, and I wonder if the House Governor is merciful enough to let us go outside freely. I don’t know much about them at all except that they’re all either younger than twenty-five or approaching seventy—the latter being from the first generation, and they’re a rarity. By now, much of the first generation has watched enough of its children die prematurely, and they are unwilling to experiment on yet another generation. They even join the protest rallies, violent riots that leave irreparable damage.

My brother. He would have known immediately that something was wrong when I didn’t come home from work. And I’ve been gone for three days. No doubt he’s beside himself; he warned me about those ominous gray vans that roll slowly through city streets at all hours. But it wasn’t one of those vans that took me at all. I could never have seen this coming.

It’s the thought of my brother, alone in that empty house, that forces me to stop pitying myself. It’s counterproductive. Think. There must be some way to escape. The window clearly isn’t opening. The closet leads to only more clothes. The chute where the boy threw the dirty dishrag is only inches wide. Maybe, if I can win the House Governor’s favor, I’ll be trusted enough to wander the garden alone. From my window the garden looks endless. But there has to be an end somewhere. Maybe I can find an exit by squeezing through a hedge or scaling a fence. Maybe I’ll be one of the public brides, flaunted at televised parties, and there will be an opportunity to slip quietly into the crowd. I have seen so many reluctant brides on television, and I’ve always wondered why the girls don’t run. Maybe the cameras neglect to show the security system that keeps them trapped.

Now, though, I worry that I may never even have a chance to make it to one of those parties. For all I know, it will take years to earn a House Governor’s trust. And in four years, when I turn twenty, I’ll be dead.

I try the doorknob, and to my surprise it isn’t locked. The door creaks open, revealing the hallway.

Somewhere a clock is ticking. There are a few doors lining the walls, mostly closed, with dead bolts. There’s a dead bolt on my door as well, but it’s open.

I tread slowly, my bare feet giving me an advantage because on this rich green carpet I’m practically silent. I pass the doors, listening for sound, signs of life. But the only sound comes from the door at the end of the hallway that’s slightly ajar. There are moans, gasps.

I freeze where I stand. If the House Governor is with one of his wives trying to impregnate her, it would only make things worse for me if I walked in on it. I don’t know what would happen—I’d either be executed or asked to join, probably, and I can’t imagine which would be worse.

But no, the sounds are strictly female, and she’s alone. Cautiously I peek through the slit in the door, then push the door open.

“Who’s there?” the woman murmurs, and this throws her into a rage of coughs.

I step into the room and find that she’s alone on a satin bed. But this room is far more decorated than mine, with pictures of children on the walls, and an open window with a billowing curtain. This room looks lived in, comfortable, and nothing like a prison.

On her nightstand there are pills, vials with droppers, empty and near-empty glasses of colored fluids. She props herself on her elbows and stares at me. Her hair is blond, like mine, but its shade is subdued by her sallow skin. Her eyes are wild. “Who are you?”

“Rhine,” I give my name quietly, because I’m too unnerved to be anything but honest.

“Such a beautiful place,” she says. “Have you seen the pictures?”

She must be delirious, because I don’t understand what she’s saying. “No,” is all I say.

“You didn’t bring me my medicine,” she says, and drifts gracefully back to her sea of pillows with a sigh.

“No,” I say. “Should I get something?” Now it’s clear that she is delirious, and if I can make up an excuse to leave, maybe I can return to my room and she’ll forget I was even here.

“Stay,” she says, and pats the edge of her bed. “I’m so tired of these remedies. Can’t they just let me die?”

Is this what my future as a bride will look like? Being so entrapped I’m not even allowed the freedom of death?

I sit beside her, overwhelmed by the smell of medication and decay, and beneath that, something pleasant. Potpourri—perfumed, dehydrated flower petals. That melodic smell is everywhere, surrounding us, making me think of home.

“You’re a liar,” the woman says. “You didn’t come to bring my medicine.”

“I never said I did.”

“Well, then, who are you?” She reaches her trembling hand and touches my hair. She holds up a lock of it for inspection, and then a horrible pain fills her eyes. “Oh. You’re my replacement. How old are you?”

“Sixteen,” I say, again startled into honesty. Replacement? Is she one of the House Governor’s wives?

She stares at me for a while, and the pain begins to recede into something else. Something almost maternal. “Do you hate it here?” she says.

“Yes,” I say.

“Then you should see the verandah.” She smiles as she closes her eyes. Her hand falls away from my hair. She coughs, and blood from her mouth splatters my nightgown. I’ve had nightmares that I’ll enter a room where my parents have been murdered and lie in a pool of fresh blood, and in those nightmares I stand in the doorway forever, too frightened to run. Now I feel a similar terror. I want to go, to be anywhere but here, but I can’t seem to make my legs move. I can only watch as she coughs and struggles, and my gown becomes redder for it. I feel the warmth of her blood on my hands and face.

I don’t know how long this goes on for. Eventually someone comes running, an older woman, a first generation, holding a metal basin that sloshes soapy water. “Oh, Lady Rose, why didn’t you press the button if you were in pain?” the basin woman says.

I hurry to my feet, toward the door, but the basin woman doesn’t even notice me. She helps the coughing woman sit up in the bed, and she peels off the woman’s nightgown and begins to sponge the soapy water over her skin.

“Medicine in the water,” the coughing woman moans. “I smell it. Medicine everywhere. Just let me die.”

She sounds so horrible and wounded that, despite my own situation, I pity her.

“What are you doing?” a voice whispers harshly behind me. I turn and see the boy who brought my lunch earlier, looking nervous. “How did you get out? Go back to your room. Hurry, go!” This is one thing my nightmares never had, someone forcing me into action. I’m grateful for it. I run back to my open bedroom, though not before crashing into someone standing in my path.

I look up, and I recognize the man who has caught me in his arms. His smile glimmers with bits of gold.

“Why, hello,” he says.

I don’t know what to make of his smile, whether it’s sinister or kind. It takes only a moment longer for him to notice the blood on my face, my gown, and then he pushes past me. He runs into the bedroom where the woman is still in a riot of coughs.

I run into my bedroom. I tear off the nightgown and use the clean parts of it to scrub the blood from my skin, and then I huddle under the comforter of my bed, holding my hands over my ears, trying to hide from those awful sounds. This whole awful place.

The sound of the doorknob awakens me this time. The boy who brought my lunch earlier is now holding another silver tray. He doesn’t meet my eyes; he crosses the room and sets the tray on my nightstand.

“Dinner,” he says solemnly.

I watch him from where I’m huddled in my blankets, but he doesn’t look at me. He doesn’t even raise his head as he picks the sullied nightgown off the floor, splattered with Lady Rose’s blood, and disposes of it in the chute. Then he turns to go.

“Wait,” I say. “Please.”

He freezes, with his back to me.

And I’m not sure what it is about him—that he’s close to my own age, that he’s so unobtrusive, that he seems no happier to be here than I am—but I want his company. Even if it can only be for a minute or two.

“That woman—,” I say, desperate to make conversation before he leaves. “Who is she?”

“That’s Lady Rose,” he says. “The House Governor’s first wife.” All Governors take a first wife; the number doesn’t refer to the order of marriage, but is an indication of power. The first wives attend all the social events, they appear with their Governors in public, and, apparently, they are entitled to the privilege of an open window. They’re the favorites.

“What’s wrong with her?”

“Virus,” he says, and when he turns to face me, he has a look of genuine curiosity. “You’ve never seen someone with the virus?”

“Not up close,” I say.

“Not even your parents?”

“No.” My parents were first generation, well into their fifties when my brother and I were born, but I’m not sure I want to tell him this. Instead I say, “I try really hard not to think about the virus.”

“Me too,” he says. “She asked for you, after you left. Your name is Rhine?”

He’s looking at me now, so I nod, suddenly aware that I’m naked under these blankets. I draw them closer around myself. “What’s your name?”

“Gabriel,” he says. And there it is again, that almost smile, hindered by the weight of things. I want to ask him what he’s doing in this awful place with its beautiful gardens and clear blue pools, symmetrical green hedges. I want to know where he came from, and if he’s planning on going back. I even want to tell him about my plan to escape—if I ever formulate a plan, that is. But these thoughts are dangerous. If my brother were here, he’d tell me to trust nobody. And he’d be right.

“Good night,” the boy, Gabriel, says. “You might want to eat and get some sleep. Tomorrow’s a big day.” His tone implies I’ve just been warned of something awful ahead.

He turns to leave, and I notice a slight limp in his walk that wasn’t there this afternoon. Beneath the thin white fabric of his uniform, I can see the shadow of bruises beginning to form. Is it because of me? Was he punished for making my escape down the hallway possible? These are more questions that I don’t ask.

Then he’s gone. And I hear the click of a lock turning in the door.

morning, but a parade of women. They’re first generation, if the gray hair is any indication, though their eyes still sparkle with the vibrancy of youth. They are chattering among themselves as they yank the blankets from me.

One of the women looks over my naked body and says, “Well, at least we won’t have to wrestle this one out of her clothes.”

This one. After everything that’s happened, I almost forgot that there are two others. Trapped in this house somewhere, behind other locked doors.

Before I can react, two of the women have grabbed me by the arms and are dragging me toward the bathroom that connects to my room.

“Best if you don’t struggle,” one of them says cheerfully. I stagger to keep pace with them. Another woman stays behind to make my bed.

In the bathroom they make me sit on the toilet lid, which is covered in some sort of pink fur. Everything is pink. The curtains are flimsy and impractical.

Back home we covered our windows with burlap at night to give the impression of poverty and to keep out the prying eyes of new orphans looking for shelter and handouts. The house I shared with my brother has three bedrooms, but we’d spend our nights on a cot in the basement, sleeping in shifts just in case the locks didn’t hold, using our father’s shotgun to guard us.

Frilly, pretty things have no place in windows. Not where I come from.

The colors are endless. One woman draws a bath while the other opens the cabinet to a rainbow of little soaps that are shaped like hearts and stars. She drops a few of them into the bathwater, and they sizzle and dissolve, leaving a frothy layer of pink and blue. Bubbles pop like little fireworks.

I don’t argue when I’m told to get into the tub. It’s awkward being naked in front of these strangers, but the water looks and smells appealing. It’s so unlike the bleary yellowed water that runs through the rusty pipes in the house I shared with my brother.

Shared. Past tense. How could I let myself think this way?

I lie in the sweet-smelling water, and the bubbles pop against my skin, bringing samples of cinnamon and potpourri and what I imagine real roses must smell like. But I will not be hypnotized by the wonder of these small things. Defiantly I think of the house I share with my brother, the house where my mother was born at the threshold of the new century. It has brick walls still imprinted with the silhouette of ivy that has long since died. It has a fire escape with a broken ladder, and on its street all the houses are close enough together that as a child I would hold my arms out my bedroom window to hold the hands of the little girl who lived next door. We would string paper cups across the divide and talk to each other in giggles.

That little girl was orphaned young. Her parents were the new generation. She barely knew her mother, her father fell ill, and then one morning I reached for her and she was gone.

I was inconsolable, that girl having been my first true friend. I still think of her bright blue eyes sometimes, the way she’d toss peppermints at my bedroom window to wake me for a game of paper-cup telephone. Once she was gone, my mother held the string we had used for our game of telephone, and she told me it was kite string, that when she was a little girl she would spend hours in the park flying kites. I asked her for more stories of her childhood, and on some nights she gave them to me. Stories of towering toy stores and frozen lakes where she would skate swanlike into figure eights, and of all the people who had passed beneath the very windows of this very house when it was young and covered in ivy, and when the cars were parked in neat, shiny rows along the street, in Manhattan, New York.

When she and my father died, my brother and I covered the windows with burlap potato and coffee bean sacks. We took all our mother’s beautiful things, all our father’s important clothes, and stuffed them into trunks that locked. The rest we buried in the yard, late at night, beneath the ailing lilies.

This is my story. These things are my past, and I will not allow them to be washed away. I will find a way to have them back.

“She has such agreeable hair,” one of the women says, scooping warm cupful after cupful of frothy water over my head. “Such a lovely color, too. I wonder if it’s natural.” Of course it’s natural. What else would it be?

“I bet that’s what the Governor liked about her.”

“Let me see,” says the other woman, cupping my chin and tilting it. She studies my face and then gasps, letting her hand flutter spasmodically against her heart. “Oh, Helen, look at this girl’s eyes!”

They both stop bathing me long enough to look at me. Really look at me, for the first time.

My eyes are usually the first thing people notice, the left eye blue and the right eye brown, just like my brother’s. Heterochromia; my parents were geneticists, and that was the name they gave my condition. I might have asked them more about it when I grew older, if I’d had the chance. I had always thought the heterochromia was a useless genetic glitch, but if the women are right and my eyes are what the Governor noticed, heterochromia has saved my life.

“Suppose those are real?” one woman asks.

“What else would they be but real?” This time I speak aloud, and they’re startled, then delighted. Their doll has a voice. And suddenly they’re all questions. Where am I from, do I know where I am, don’t I just love the view, do I like horses—there’s a lovely stable—do I prefer my hair up or down?

I answer none of these. I will share nothing with these strangers—however well intentioned they may be—who are a part of this place. The questions come so fast that I wouldn’t know where to begin anyway, and then there’s a soft knock at the door.

“We’re getting her ready for the Governor,” one of the women says.

The muffled voice on the other side of the door is soft, gentle, and young. “Lady Rose would like to speak to her right this moment, please.”

“We’re only half done bathing her! And her nails—”

“Excuse me,” the voice on the other side of the door says patiently, “I have a direct order to bring her now, whatever condition she may be in.”

Lady Rose is apparently someone who has the final say in things, because the women are tugging me to my feet, patting me dry with a pink towel, brushing my wet hair, and slipping me into a robe that feels like waves of silk against my skin. Whatever was in that bathwater has heightened my neurons, left me feeling unpeeled and exposed. I still feel as though bubbles are popping against my skin.

When the door opens, I see that the voice belongs to a little girl, barely half my height. She is dressed like the older women, though, in the feminine version of the white blouse Gabriel wore, with a tiered black skirt, where Gabriel had worn black pants. Her hair is braided into a circle around her head, and her cheeks bloom into apple shapes when she smiles at me. “You’re Rhine?”

I nod. “I’m Deirdre,” she says, and puts her hand in mine. It is cool and soft. “It’s just this way,” she says, and leads me out of my room and along the hallway down which I made my brief escape yesterday.

“Now,” the girl says, nodding seriously, her eyes focusing ahead. “Just speak if spoken to; she doesn’t like questions, so you’d do best not to ask any; refer to her as Lady Rose; there’s a button above her night table, a white one—press it if she becomes ill. She’s in charge of things. The House Governor will do anything she asks, so be sure to stay on her good side.”

We stop before the door, and Deirdre reties the belt of my robe into a perfect bow. She knocks on the semi-open door and says, “Lady Rose? I brought her like you said.”

“Well, then, let her in,” Rose snaps. “And go make yourself useful somewhere else.”

As she turns to leave, Deirdre clasps both of her hands around one of mine. Her eyes are round as moons. “And please,” she whispers, “try to avoid the topic of death.”

When she’s gone, I push the door open and step only as far as the threshold. From here I can smell the medications Rose complained of yesterday. I see the assortment of lotions, pills, and bottles on her nightstand.

She’s sitting up today, in a satin-upholstered divan by the window. Her blond hair is tangled in sunlight, and her skin appears to be less sallow. There’s color in her cheeks, and at first I think she’s feeling better, but when she beckons me closer, I can see the unusual, almost neon pink of her cheeks, and I know it must be cosmetics. I know the red of her lips must not be real either. What are real are her eyes, incredibly brown things that stare at me with intensity, with youth. I try to imagine a world of natural humans, when twenty was youthful, when it was years from a death sentence.

Natural humans used to live for at least eighty years, my mother told me. Sometimes a hundred. I hadn’t believed her.

Now I can see what she meant. Rose is the first twenty-year-old I’ve spoken to at length, and though she’s stifling a cough that sprays blood into her fist, her skin is still smooth and soft. Her face is still full of light. She doesn’t look very different from, or very much older than, me.

“Sit,” she tells me. I find a chair across from her.

There are wrappers all over the floor around her, and a bowl filled with candies on her divan. When she speaks, I can see that her tongue is bright blue. She fiddles with another candy in her long fingers, bringing it close to her face, almost looking like she’ll kiss it. Instead she lets it fall back into the bowl.

“Where are you from?” she asks. Her voice has none of the peevishness she showed Deirdre at the door. Her thick eyelashes flutter up. She watches an insect spiral around her and disappear.

I don’t want to tell her where I’m from. I’m supposed to sit here and be polite, but how can I? How can I when I’m made to sit and watch her die so I can be given to her husband and forced to bear children I never wanted?

So I say, “Where were you from when they took you?”

I’m not supposed to ask her questions, and as soon as I’ve asked it, I realize I have stepped on a land mine. She’ll be screaming for Deirdre or her husband, the House Governor, to take me away. Lock me in a dungeon for the next four years.

To my surprise she only says, “I was born in this state. This town, in fact.” She reaches up behind her, takes a picture from the wall, and holds it out for me. I lean in to get a look.

The photo is of a young girl standing beside a horse. She’s holding the reins, and her smile is so bright that her teeth dominate her face. Her eyes are nearly closed with all the delight of it. Beside her, a much taller boy stands with his hands behind his back. His smile is more controlled, shy, as though he hadn’t meant to smile but couldn’t help himself in the moment.

“This was me,” Rose says of the girl in the photo. Then she traces her finger over the boy’s outline. “This is my Linden.” For a moment she seems lost in the sight of him. A little smile comes to her painted lips. “We grew up together.”

I’m not sure what to say to this. She is so lost in this memory, and so blind to my imprisonment. But still I feel sorry for her. In another time, under different circumstances, she would not have needed to be replaced.

“See?” she says, still pointing to the photo. “This is in the orange grove. My father owned acres of them. Here in Florida.”

Florida. My heart sinks. I’m in Florida, on the bottom of the East Coast, more miles from home than I can count. I miss my ivy-silhouetted house. I miss the distant commuter trains. How will I ever find my way back to them?

“They’re lovely,” I say of the oranges. Because it’s true, they are lovely. Things seem to thrive in this place. I would never have suspected that the vibrant girl standing beside her horse in the grove could be dying now.

“Aren’t they?” she says. “Linden prefers flowers, though. There are orange blossom festivals in the spring. That’s his favorite. In the winter there are snow festivals, and solstice dances—but he doesn’t like those. Too loud.”

She unwraps a green candy and pops it into her mouth. She closes her eyes for a moment, apparently savoring the flavor. The candies are each a different color, and this one, the green, has a peppermint smell that takes me back to my childhood. I think of the little girl who would throw her candies into my bedroom, how their smell would fill the paper cup into which I’d respond to her voice.

When Rose speaks again, her tongue has taken on the emerald color of the candy. “But he’s an excellent dancer. I don’t know why he’s such a wallflower.”

She sets the picture on the divan in a sea of wrappers. I can’t decide what to make of this woman, who is weary and so sad, and who snapped at Deirdre but is treating me like a friend. My curiosity quells my bitterness for the moment. I think, in this strange world of beautiful things, there may be some humanity after all.

“Do you know how old Linden is?” she asks me. I shake my head. “He’s twenty-one. We’d planned to marry since we were children, and I suppose he thought all these medicines would keep me alive for four extra years. His father is a very prominent doctor—first generation. Toiling away at finding an antidote.” She says that last bit fancifully, letting her fingers flutter in the air. She does not think an antidote is possible. Many do, though. Where I come from, hordes of new orphans will file into laboratories, offering themselves up to be guinea pigs for a few extra dollars. But an antidote never arrives, and a thorough analysis of our gene pool turns up no abnormalities to explain this fatal virus.

“But you,” Rose says. “Sixteen is perfect. You can spend the rest of your lives together. He won’t have to be alone.”

I feel the room go cold. Outside there are things buzzing and chirping in the infinite garden, but they are a million miles from me. I had almost, for just a moment, forgotten why I’m here. Forgotten how I arrived. This beautiful place is dangerous, like milky white oleanders. The thriving garden is meant to keep me inside.

Linden stole his brides so he wouldn’t have to die alone. What about my brother, alone in that empty house? What about the other girls who were shot to death in that van?

My anger is back. My fists clench, and I wish someone would come to take me out of this room, even if it means being imprisoned somewhere else in this house. I cannot bear another moment in Rose’s presence. Rose with her open window. Rose who has mounted a horse and ridden beyond the orange groves. Rose who intends to pass her death sentence on to me once she’s gone.

My wish comes true, to make matters worse. Deirdre returns and says, “Excuse me, Lady Rose, the doctor is here to prepare her for Governor Linden.”

I’m led down the hall again, and into an elevator that requires a key card in order to work. Deirdre stands beside me, looking rigid and worried. “You’ll meet Housemaster Vaughn tonight,” she whispers. The blood has drained from her face, and she looks at me in a way that reminds me she’s just a child. Her lips purse in—what? Sympathy? Fear? I don’t know, because the elevator doors open and she returns to herself, guiding me down another, darker hallway that smells of antiseptic, and through another door.

I wonder if she has any advice for me this time, but she’s not even given the chance to speak before a man says, “Which one is this?”

“Rhine, sir,” Deirdre says, not raising her eyes. “The sixteen-year-old.”

I wonder, briefly, if this man is the Housemaster or the Governor who’s to be my husband, but I don’t have the chance to even look at him before there’s a stinging pain in my arm. I have only time to process what I’m seeing: a sterile, windowless room. A bed with a sheet, and restraints where arms and legs might go.

Keeping in theme with all the other things in this place, the room fills with shimmering butterflies. They all quiver, and then burst like the strange bath bubbles. Blood everywhere in their wake. Then blackness.

doors and windows and barricaded ourselves in the basement for the night. The tiny refrigerator hums in the corner; the clock is ticking; the lightbulb swings on its wire, doing erratic things with the light. I think I hear a rat in the shadows, foraging for crumbs.

Rowan is snoring on the cot, which is unusual, because he never does. But I don’t mind. It’s nice to hear the sound of another human, to know that I’m not alone. That in a second he would be awake if there were any trouble. As twins, we make a great team. He has the muscles, and his aim with the shotgun never misses, but I’m smaller and faster, and sometimes more alert.

We’ve only had one thief ever who was armed, the year I turned thirteen. Mostly the thieves are small children who will break windows or attempt to pick the lock, and they only stay long enough to realize there’s nothing to eat or nothing worth stealing. They’re pests, and I would just as soon feed them so they’d go away. We have plenty to spare. But Rowan won’t allow it. Feeding one is feeding them all, and we don’t own the goddamn city, he’d say. That’s what orphanages are for. That’s what laboratory wages are for. Or how about the first generations? he’d say; how about the first generations do something because they caused this whole mess.

The armed thief was a man twice my size, at least into his twenties. He somehow picked the lock on our front door without making a sound, and he figured out quickly that the residents of our little house were hiding somewhere, guarding what was worth taking. It was Rowan’s watch that hour, but he’d fallen asleep after a full day of physical labor. He takes work where and when he can get it, and it’s always arduous; he’s always in pain at the end of the day. Long ago, America’s factory jobs were outsourced to other industrialized countries. Now, because there’s no importing, most of New York’s towering buildings have been converted to factories that make everything from frozen food to sheet metal. I’m usually able to find work handling wholesale orders by phone; Rowan finds work easily in shipments and delivery, and it exhausts him more than he cares to admit. But the pay is always cash, and we’re always able to buy more than we need in terms of food. Shopkeepers are so grateful to have paying customers—as opposed to the penniless orphans who always try to steal the essentials—that they give us deals on extras like electrical tape and aspirin.

So there we were, both asleep. I awoke with a blade to my throat, looking into the eyes of a man I did not know. I made a small sound, not even a whimper, but that was all it took for my brother to jolt back to consciousness, gun at the ready.

I was helpless, paralyzed. Small thieves I could handle, and most thieves did not want to kill us, not if they could help it. They only made meager threats on the hope of getting food, a piece of jewelry, and if they were smaller than you, they would just run away when you caught them. They were only trying to survive however they could.

“Shoot me, and I cut her,” the man said.

There was a loud sound, like the time one of our pipes burst, and then I saw a line of blood roll over the man’s brow. It took a second for me to realize there was a red bullet hole in his forehead, and then the knife went slack against my neck. I grabbed it, kicked him away from me. But he was already dead. I sat up, eyes bulging, gasping. Rowan was on his feet, though, checking to be sure the man was really dead, not wanting to waste another bullet if it wasn’t necessary. “Goddamn it,” he said, and kicked the man. “I fell asleep. Damn it!”

“You were tired,” I said reassuringly. “It’s okay. He would have gone away if we’d fed him.”

“Don’t be so naive,” Rowan said, and lifted the dead man’s arm pointedly. It was then that I noticed the man’s gray coat. The clear mark of a Gatherer on the job. “He wanted—,” Rowan began, but couldn’t finish the thought aloud. It was the first time I’d ever seen him tremble.

I had thought, before that night, that Gatherers swept young girls from the street. While this is true, it isn’t always the case. They can stake a girl out, follow her home, and wait for an opportunity. That is, if they think she’s worth the trouble, if they think she’ll get a good price. And that’s what had happened. That’s why the man had broken into our home. Now my brother refuses to let me go anywhere unless he’s with me. He worries over our shoulders, peers into alleyways we pass. We’ve added bolts to the door. We’ve strung the kitchen floor in a labyrinth of kite strings and empty aluminum cans so that we’ll be alerted—loudly—to any intruders before they can hope to break into our basement.

I hear something else now, something I at first assume is another rat scurrying around upstairs. It would be the only thing small enough to wind a path around our trap. But then the basement door begins to rattle at the top of the steps. The bolts pop open, one at a time.

Behind me, Rowan has stopped snoring. I whisper his name. I say I think someone has broken in. He doesn’t answer me. I turn around, and the cot is empty.

At the top of the stairs, the basement door flies open. But instead of the darkness of our house, there’s sunlight, and the most breathtaking garden I have ever seen. I barely have time to take it all in before the doors close in front of me. The doors of a gray van, a van full of frightened girls.

“Rowan,” I gasp, and throw myself upright.

Awake. I’m awake now, trying to console myself. But reality does not offer a safe haven. I’m still in this Florida mansion, still the intended bride of the House Governor, and Rose is gasping for her life down the hall while voices try to soothe her.

My legs and hips feel sore when I stretch them against the satin sheets. I peel back the blankets, assess myself. I’m wearing a plain white slip. My skin is tingling and hairless. My nails have been rounded and polished. I’m back in my bedroom, with its window that doesn’t open and its bathroom so pink it’s practically glowing.

As if on cue, my bedroom door opens, and I don’t know what to expect. Gabriel, beaten and limping as he brings me a meal; a parade of first generations coming to exfoliate, fluff, and perfume what’s left of my skin; a doctor with a needle and another scary table, this time on wheels. But it’s only Deirdre, carrying what looks to be a heavy white package in her tiny arms.

“Hello,” she says, in a tone that’s gentle as only a child’s can be. “How are you feeling?”

My answer wouldn’t be kind, so I don’t say anything.

She flits across the room, wearing a wispy white dress rather than her traditional uniform.

“I’ve brought your gown,” she says, setting the package on the dressing table and undoing the bow that was holding it together. The dress is taller than she is, and it drags luxuriously along the floor as she holds it up. It glitters with diamonds and pearls.

“It should be your size,” Deirdre says. “They measured you while you were out, and I made some alterations to be sure. Try it on.”

The last thing I want to do is try on what is clearly my wedding gown, just so I can meet House Governor Linden, the man responsible for my kidnapping, and Housemaster Vaughn, whose name alone made Deirdre go pale in the elevator. But she’s holding up the dress and looking so sympathetic and innocent about it that I don’t want to give her a hard time. I step into the gown and allow myself to be zipped in.

Deirdre stands on the ottoman at the dressing table to tie the choker for me. Her deft little hands make such perfect bows. And the gown is a remarkable fit. “You made this?” I ask her, not hiding my amazement. A blush spreads across her apple cheeks, and she nods as she steps down.

“The diamonds and the pearls take the longest time to thread,” she says. “The rest is easy.”

The dress is strapless, shaped like the top of a heart at my collarbone. The train is V-shaped. And I suppose, from an aerial view, I could be a satiny white heart as I make my way down the aisle. At least I can’t imagine a lovelier thing to wear on my way to lifelong imprisonment.

“You made three wedding dresses by yourself?” I say.

Deirdre shakes her head and gently guides me to sit on the ottoman. “Just yours,” she says. “You’re my keeper; I’m your domestic. The other wives each have their own.”

She opens a drawer in the dressing table, and it is lush with cosmetics and hair barrettes. With a rouge brush in her hand, she gestures to the buttons on the wall just above my night table. “Press the white one if you need anything, that’s how you can reach me. Blue is the kitchen.”

She begins to paint my face, blending and brushing colors onto my skin, holding my chin up to inspect me. Her eyes are serious and wide. When she’s satisfied, she starts on my hair, brushing and weaving it around curlers, and prattling on about information she feels will be useful to me.

“The wedding will be held in the rose garden. It goes in order of age, youngest first. So there will be a bride before you and a bride after. There’s the exchange of vows, of course, but the vows will be read for you; you won’t be required to speak. Then there’s the exchange of the rings, and let’s see what else …”

Her voice trails off, into a sea of description; floating candles; dinner arrangements; even how softly I should speak.

But everything she says blurs into one hideous mess. The wedding is tonight. Tonight. I have no hope of escaping before it occurs; I haven’t even been able to open a window; I haven’t even seen the outside of this wretched place. I feel sick, winded. I’d settle for being able to open the window not to escape but to gasp in the fresh air. I open my mouth to take a deep breath, and Deirdre pops a red candy into my mouth.

“It’ll make your breath sweet,” she says. The candy dissolves instantly, and I’m flooded with the flavor of something like strawberries and too much sugar. It’s overwhelming at first, and then it subsides, tastes natural, even settles my anxiety somewhat.

“There now,” Deirdre says, seeming pleased with herself. She nudges me so that I’m facing the mirror for the first time.

I’m stunned by what I see.

My eyelids have been painted pink, but it is not the obnoxious pink of the bathroom here. It’s the color between the reds and yellows at sunset. It sparkles as though full of little stars, and recedes into light purples and soft whites. My lips are done to match, and my skin is shimmering.

I look, for the first time, like I am not a child. I am my mother in her party dress, those nights she spent dancing with my father in the living room after my brother and I had gone to bed. She would come into my bedroom later to kiss me while she thought I slept. She would be sweaty and perfumed and delirious with love for my father. “Ten fingers, ten toes,” she would whisper into my ear, “my little girl is safe in her dreams.” Then she would leave me feeling like I’d just been enchanted.

What would my mother say to this girl—this almost-woman—in the mirror?

As for myself, I’m speechless. With her talent for color Deirdre has made my blue eye brighter, my brown eye nearly as intense as Rose’s stare. She has dressed me and painted me well for the role: I am soon to become Governor Linden’s tragic bride.

I think it speaks for itself, but in the mirror I can see Deirdre behind me twisting her hands, waiting to hear what I think of her work. “It’s beautiful,” is all I can say.

“My father was a painter,” she says with a hint of pride. “He tried his best to teach me, but I don’t know if I’ll ever be as good. He told me anything can be a canvas, and I suppose you’re my canvas now.”

She says no more about her parents, and I don’t ask.

She touches up my hair for a while, which has been curled into ringlets and pinned back with a simple white headband. This goes on until the watch on Deirdre’s wrist begins to beep. And then she helps me into my un-sensible high heels and carries the train of my dress down the hallway. We descend in the elevator and weave through a maze of hallway after hallway, and just when I’m beginning to think this house has no end, we come to a large wooden door. Deirdre goes ahead of me, opens the door just barely, and pokes her head in. She appears to be talking to someone.

Deirdre steps back, and a little boy peers out at me. He’s her size or close to it. His eyes sweep across me, head to toe. “I like it,” he says.

“Thank you, Adair. I like yours, too,” Deirdre says. There’s such professionalism in her young voice. “Are we almost ready to begin?”

“All ready here. Check with Elle.”

Deirdre disappears behind the door with him. There’s more talking, and when the door opens, another little girl peers out at me. Her eyes are big and green; she claps her hands together excitedly. “Oh, it’s lovely!” she shrieks, and then disappears.

When the door opens again, Deirdre takes my hand and leads me into what can only be a sewing room. It’s small and windowless, cluttered with bolts of fabric and sewing machines, and everywhere ribbons drip from shelves and lay strewn across tables. “The other brides are all ready,” Deirdre says. She looks around herself to be sure no one else can hear, and then whispers to me, “But I think you’re the prettiest.”

The other brides stand in corners of the room opposite each other, being fussed over by their domestics, all of whom are dressed in white. The little boy, Adair, is straightening the white velvet bodice on a willowy bride with dark hair, who stares despondently at her shoulder and does not seem to mind being prodded.

The little girl, whom I presume to be Elle, is adjusting pearl barrettes in the hair of a bride who could not tip the scale above a hundred pounds. This bride has her red hair done up in a beehive, and her dress is white with just a slight glimmer of rainbow hues when she moves. The bodice has big translucent butterfly wings in back that seem to be hemorrhaging glitter, which I realize is some sort of illusion, because none of this glitter ever touches the ground. The bride is wriggling uncomfortably in her bodice, though, a bit too small to fill in the chest of it.

On tiptoes the redhead wouldn’t even reach my shoulder; she is clearly too young to be a bride. And the willowy girl is too forlorn. And I am too unwilling.

Yet here we are.

This dress is so comfortable against my skin, and Deirdre is so proud, and here I stand in the room where I suppose my wardrobes are to be constructed for the rest of my life. And all I can think of is how I can escape. An air duct? An unlocked door?

And, of course, I think of my twin brother, Rowan. Without each other we are only half of a whole. I can hardly stand the thought of him all alone in that basement at night. Will he search through the scarlet district for my face in a brothel? Will he use one of the delivery trucks from his job to look for my body on roadsides? Of all the things he could ever do, of all the places he could ever search, I am certain he will never find this mansion, surrounded by orange groves and horses and gardens, so very far from New York.

I will have to find him instead. Stupidly, I look to the too-small air duct for a solution where there is none.

The domestics summon each of us brides to the center of the room. It’s the first time we’ve been able to look at one another, really. It was so dark in that van, and then we’d been too horrified to do anything but keep our eyes forward when we were assessed. Add the sleeping gas in the limo, and we’re still perfect strangers.

The redhead, the little one, is hissing to Elle that her bodice is now laced too tight, and how can she be expected to stay still during the ceremony—the most important moment of her life, she adds—if she can hardly breathe?

The willowy girl stands beside me, saying and doing nothing as Adair perches on a stepladder and dots her braided hair with tiny fake lilies.

There’s a knock on the door, and I don’t know what I’m expecting. A fourth bride, perhaps, or for the Gatherers to come and shoot us all. It’s only Gabriel, though, holding a large cylinder and asking the domestics if the brides are ready. He doesn’t look at any of us. When Elle tells him we’re ready, he lays the cylinder on the ground, and with a mechanical whirr it somehow unrolls a long red carpet that stretches out into the hallway. Gabriel disappears into the shadows.

Strange music begins to radiate, seemingly from the ceiling tiles. The domestics arrange us in a row, youngest to oldest, and we begin to march. It’s amazing how in sync our footsteps are, for having no practice and considering we were all dragged to this place in unconscious heaps after the time spent in that van. In a few minutes we’ll be sister wives. It’s a term I’ve heard on the news, and I don’t know what it means. I don’t know if these girls will be my allies or enemies, or if we’ll even coexist after today.

The bride in front of me, the redhead, the little one, seems to be skipping. Her wings flutter and bounce. Glitter swirls around her. If I didn’t know better, I could swear she’s excited about all this.

The carpet leads to an open door to the outside. This is what Deirdre called the rose garden, which is abundantly clear by the rosebushes that make up the high walls around us. They are an extension of the hallway, really, and despite the open sky overhead, I feel no less trapped than I did inside.

The dusk sky is full of stars, and absently I think that back home I would not dream of being outside at this hour. The door would be bolted, the noise trap laid out in the kitchen. Rowan and I would be having a quiet dinner and washing it down with tea, and then we’d watch the nightly news to see about available jobs and to update ourselves on the state of our world, hoping dismally that one day there might be a positive change. Since the old lab exploded four years back, I’ve been hoping a new lab will replace it, so that pro-science research jobs will be created, and so that someone can discover an antidote; but orphans have made a home for themselves in the ruins of the old lab. People are giving up, accepting their fate. And the news is nothing but job listings and televised events put on by the wealthier class—House Governors and their sad brides. It’s supposed to encourage us, I guess. Give the illusion that the world isn’t ending.

I don’t have a chance to feel the oncoming wave of homesickness before I’m nudged into the clearing at the end of the rosebush hallway and made to stand in a semi-circle with the other brides.

The clearing is sudden and gaping, and a relief. The garden at once becomes enormous, a city bustling with fireflies and little flat candles that seem to be floating in place—I think Deirdre called them tea lights. There are fountains trickling into tiny ponds, and I can see now that the music is somehow being amplified from a keyboard that plays itself, the keys lighting up as the notes radiate out, sounding like a full band of strings and brass. I know the melody; my mother used to hum it: “The Wedding March,” the theme of weddings back in her own mother’s day.

I’m led to a gazebo at the center of the clearing with the two others, where the red carpet becomes a large circle. There is a man beside us in white robes, and the domestics take their places opposite us, their hands clasped in front of them as though in prayer. The youngest bride giggles as a firefly spirals before her nose and disappears. The oldest bride stares into space with eyes as gray as the evening sky. I just do what I can to not stand out, to blend in, which I suspect is impossible if the Governor has taken a liking to my eyes.

I don’t know much about traditional weddings; I’ve never attended one, and my parents, like most couples at that time, were married in city hall. With the human race dying off so young, hardly anybody gets married anymore. But I suppose this is how it used to be, more or less: the waiting bride, the music, the groom in a black tuxedo approaching. Linden, the House Governor, my soon-to-be husband, is led to us on the arm of a first generation man. Both of them are tall and pale. They part at the gazebo, and Linden takes the three steps that lead him to us. He stands at the center of the carpet circle, facing us. The little redheaded one winks at him, and he smiles adoringly at her, the way a father might smile at his young daughter. But she’s not his daughter. He intends for her to carry his children.

I feel nauseous. It would be defiant enough just to vomit on his polished black shoes. But I haven’t eaten any of the food Gabriel has brought me since my first day here, and vomiting won’t win me any favoritism. My best chance at escape will be to earn Linden’s trust. The sooner I can pull that off, the better.

The man in white robes begins to speak, and the music fades to a stop.

“We are gathered here today to join these four souls in this sacred union, which will bear the fruit for generations to come …”

As the man speaks, Linden looks us over. Maybe it’s the candlelight, or the mellow evening breeze, but he doesn’t seem as menacing as before, when he selected us from the lineup. He’s a tall man with small bones that make him seem almost frail, childlike. His eyes are a bright green, and his glossy black curls hang like thick vines around his face. He is not smiling, and not grinning the way he did when he caught me running in the hallway. For a moment I wonder if he is even the same man. But then he opens his mouth, and I see the glimmer of gold in his teeth, way in the back molars.

The domestics have stepped forward. The man in white has stopped talking about how this marriage will secure future generations, and now Linden is addressing us each by name. “Cecily Ashby,” he says to the little bride. Elle opens her clasped hands, revealing a gold ring. Linden takes this ring and places it on the small bride’s hand. “My wife,” Linden says. She blushes and beams.

Before I can process what’s happening, Deirdre has opened her hands and Linden has taken the ring from her and slipped it onto my finger. “Rhine Ashby,” he says. “My wife.”

It doesn’t mean anything, I tell myself. Let him call me his wife, but once I’m on the other side of the fence, this silly little ring will mean nothing. I am still Rhine Ellery. I try to let this thought sink in, but I’ve broken into a cold sweat. My heart feels heavy. Linden catches my eyes with his, and I meet his stare. I won’t blush or flinch or look away. I won’t succumb.

He lingers a moment, and then he’s on to the third bride.

“Jenna Ashby,” he says to the next girl. “My wife.”

The man in white says, “What fate has brought together, let no man tear asunder.”

Fate, I think, is a thief.

The music starts up again, and Linden takes each of our hands long enough to guide us down the steps, one at a time. His hand is clammy and cool. It’s our first touch as husband and wife. As I move, I try to get a good look at the mansion that has imprisoned me these past few days. But it’s too massive, and I’m standing too close to see more than one side of it, and all that register are bricks and windows. I think I see Gabriel, though, for a moment as he passes one of the windows. I recognize his neatly parted hair, his wide blue eyes watching me.

Linden leaves us after that, disappearing somewhere with the first generation man he’d approached with. And the brides are herded back into the mansion. There is ivy growing along it, though, and just before I’m inside, I reach out and grab a small piece of that leafy green plant and close it in my fist. It makes me think of home, even if ivy no longer grows there.

Back in my bedroom I hide the ivy in my pillowcase before Deirdre begins fussing over me. She helps me out of my wedding gown, which she folds neatly, and then begins to spray me with something that at first attacks my senses and makes me sneeze, but then recedes into a pleasant rosy scent. She makes me sit on the ottoman again and opens the makeup drawer. She scrubs my face clean and begins again, this time painting me in dramatic reds and purples that make me appear sultry. I like it even better than the earlier look; I feel like my anger and bitterness have been manifested.

I’m dressed in a fitted red dress that matches the color of my lips, with black lace around the collar and capped sleeves. The dress only falls to about midthigh, and Deirdre tugs at the material to be sure it drapes properly. While she’s doing this, I step into yet another pair of ridiculous heels, and stare at myself in the mirror. Every curve of my body protrudes through the velvet material—my breasts, hipbones, even the ghost of ribs. “It’s a symbol that you’re no longer a child,” she explains. “That you’re ready for your husband to come to you at any time.”

After that I’m led to the elevator and down more hallways, until we reach a dining hall. The other brides are dressed in black and yellow versions of my outfit, respectively. All of us are wearing our hair down now. I’m seated between them at a long table beneath crystal chandeliers. Cecily, the redhead, is looking excited, while Jenna, the dark-haired one, seems to be coming out of her melancholy. Under the table her hand brushes mine, and I’m not sure if it’s accidental.

We all smell like flowers.

Bits of glitter still fall from Cecily’s hair.

House Governor Linden arrives, with the first generation man again. They make their way to us, and Linden raises each of our hands to his lips for a kiss, one at a time. Then he introduces the man, his father, as Housemaster Vaughn.

Housemaster Vaughn also kisses our hands, and it takes some effort for me to keep from squirming at the feel of his lips, which are papery and cold. It makes me think of a corpse. As a first generation, Housemaster Vaughn has aged well; his dark hair has only sparse flecks of gray, and his face is not horribly wrinkled. But his skin is a sickly pallid shade that would make even Rose appear vibrant by comparison. He does not smile. Everything about his touch is chilled. Even Cecily becomes subdued by his approach.

I feel a little better when Linden and Housemaster Vaughn are seated at the opposite end of the table, with Linden facing us and Housemaster Vaughn at the head. We brides sit in a row beside one another, and the other table head is left vacant. I suppose it’s where Linden’s mother would have sat, but since she’s not here, I assume she’s dead.

When Gabriel enters the room balancing a stack of plates and utensils, I find that I’m relieved by his presence. I haven’t spoken with him since last night, when he limped out of my room. I’ve been worrying that my actions led to his punishment, and that Housemaster Vaughn will decide to lock him in a dungeon for the remainder of his life. My worries always lead to dungeons; I can’t imagine a worse thing than to be imprisoned for the rest of one’s life, especially with so few years to enjoy what little there is.

Gabriel seems well enough now, though. I look closely for signs of bruises beneath his shirt, and find nothing. His limp is gone. I try to catch his gaze, hoping to give him a sympathetic or apologetic look, but he doesn’t raise his eyes to me. Four others in the same uniform follow him in, with pitchers of water, bottles of wine, a cart of extravagant foods—whole chickens basting in caramel sauces, pineapples and strawberries cut and shaped like pond lilies.

The door to the dining room is propped open as the attendants come and go. I wonder what would happen if I ran—if Gabriel or one of the others would stop me. But ultimately it’s my fear of what my new husband might do that keeps me in place, because surely if I ran, I wouldn’t make it far before I was caught. And then—what? I’d be locked in my room again, probably, forever marred as the one who can’t be trusted.

So I stay, participating in a conversation that is strained and sickeningly pleasant. Linden doesn’t talk much himself; his mind seems to be elsewhere as he brings spoonful after spoonful of soup to his mouth. Cecily smiles at him, and she even drops her spoon, I think, just so he’ll look at her.

Housemaster Vaughn is talking about the hundred-year-old gardens and how sweet the apples are. He even makes fruits and shrubbery sound ominous. It’s his voice, low and raspy. I notice that none of the help looks at him as they bring new dishes and clear away the old.

It was him, I think. He’s the one who hurt Gabriel yesterday when my door was left unlocked. Even with his smiles and harmless chatter, I can sense something dangerous in him. Something that hinders my appetite and drains the color from Deirdre’s pleasant face. Something, perhaps, more dangerous than heartsick Governor Linden, who stares past us, lost in love with a woman on death’s door.

I languish on the bed in my white slip while Deirdre rubs my sore feet. I might stop her if I weren’t so exhausted and her touch weren’t so relaxing. She’s kneeling beside me, so light that she scarcely even makes a dent in the fluffy comforter.

I lie on my stomach, hugging a pillow, and she begins to work my calves; it’s just what I need after so many hours in those high heels. She has lit some candles too, filling the room with the warm scent of obscure flowers. I’m so relaxed that I just let the words come out, so beyond worrying about being classy at this point, “So how does this wedding night work? Does he choose us in a lineup? Drug us with sleeping gas? Pool the three of us into one bed?”

Deirdre does not seem offended by my crassness. Patiently she says, “Oh, the House Governor won’t consummate his brides tonight. Not with Lady Rose …” She trails off.

I push myself up just enough to look over my shoulder at her. “What about her?”

A tragic look is on Deirdre’s face, her shoulders moving as she rubs my sore legs. “He’s very in love with her,” she tells me wistfully. “I don’t believe he’ll visit any of his new brides until she has passed on.”

It’s true that Governor Linden doesn’t come into my bedroom, and after Deirdre has blown out the candles and is gone, I eventually drift off to sleep. But in the early hours of the morning, I’m awakened by the turn of the doorknob; in recent years I’ve become a very light sleeper, and without any sleep-inducing toxin in my system, I’ve returned to my usual alertness. Still I don’t react. I wait, eyes wide open, watching my door open in the darkness.

The curly hair of the shadowy figure identifies Linden for me.

“Rhine?” He says my name for the second time in our short marriage. I want to ignore him and pretend that I’m still asleep, but I think the terrified pounding of my heart must be audible across the room. It’s irrational, but I still think a creaking door will mean Gatherers coming to shoot me in the head or steal me away. Besides, Linden has seen that my eyes are open.

“Yes,” I say.

“Get up,” he says softly. “Put on something warm; I have something to show you.”

Something warm! I think. This must mean he’s taking me outside.

To his credit, he leaves the room so I can get dressed in private. The closet illuminates when I open it, revealing rows of more clothing than I bothered to notice earlier. I choose a pair of black pants that are warm and fleecy, and a sweater that has pearls worked into the knit—Deirdre’s handiwork, no doubt.

When I open the door—which is no longer locked from the outside as it was before the wedding—I find Linden waiting for me in the hall. He smiles, loops his arm through mine, and leads me to the elevator.

It’s distressing how many hallways make up this mansion. Even if the front door were left wide open for my escape, I’m certain I’d never be able to find it. I try to make a note of where I am: a long, plain hallway with a green carpet that looks new. The walls are a creamy off-white, with the same kind of generic paintings that are in my bedroom. There are no windows, so I can’t even tell that this is the ground floor until Linden opens a door and we’re on the path to the rose garden, down the same familiar hallway of bushes. But this time we pass the gazebo. The sun has yet to come up, giving the place a subdued, sleepy feel.

Linden shows me one of the fountains, which trickles into a pond populated by long thick fish that are white, orange, and red. “Koi fish,” he tells me. “They’re originally from Japan. Heard of it?”

Geography has become such an obscure subject that I never encountered it in my brief years of schooling, before my parents’ deaths forced me to work instead. Our school was held in what was once a church, and the students barely filled out the first row of pews in full attendance. Mostly we were the children of first generations, like my brother and me, who had been raised to value education even if we’ll die without a chance to use it. And the school had an orphan or two with dreams of becoming an actor, who wanted to learn enough reading to memorize scripts. All we were taught of geography was that the world had once been made up of seven continents and several countries, but a third world war demolished all but North America, the continent with the most advanced technology. The damage was so catastrophic that all that remains of the rest of the world is ocean and uninhabitable islands so tiny that they can’t even be seen from space.

My father, however, was a world enthusiast. He had an atlas of the world as it appeared in the twenty-first century, with full-color images of all the countries and customs. Japan was a favorite of mine. I enjoyed the painted geishas with their penciled features and puckered lips. I liked the pink and white cherry blossom trees, so unlike the meager things that grow in fences along the Manhattan sidewalks. The whole country of Japan seemed to be one giant color photo, glossy and bright. My brother preferred Africa, with its floppy-eared elephants and its colorful birds.

I imagined the world outside North America must have been a beautiful place. And it was my father who introduced that beauty to me. I think of these long-gone places still. A koi wriggles past me and disappears into the depth, and all I can think is that my father would have been so happy to see it.

The grief of my father’s loss is so sudden that my knees nearly buckle under the weight of it; I force tears back down my throat, past the lump that’s forming there. “I’ve heard of it,” is all I say.

Linden seems impressed. He smiles at me, and raises his hand as though to touch me, but then changes his mind and continues walking. We come to a wooden swing that’s shaped like a heart. We sit for a while, not touching, rocking slightly and staring at the horizon over the edges of the rosebushes. The color comes slowly, bits of orange and yellow, like with Deirdre’s makeup brush. Stars are still visible, fading away where the sky blushes with fiery color.

“Look,” Linden says. “Look how beautiful it is.”

“The sunrise?” I ask. It is lovely, but hardly worth getting out of bed so early. I’m so used to sleeping in shifts, taking turns keeping watch with my brother, that my body has been trained not to waste whatever sleep it can get.

“The start of a new day,” Linden says. “Being healthy enough to witness it.”

I can see sadness in his green eyes. I don’t trust it. How can I, when this is the man who paid the Gatherers so he could have me for the last years of my life? When the blood of those other girls in the van is on his hands? My sunrises may be limited, but I will not view all the rest of mine as Linden Ashby’s wife.

It’s quiet for a while. Linden’s face is lit up by the early sun, and my wedding band burns in a twist of light. I hate the thing. It took all my willpower last night not to flush it down the toilet. But if I’m to earn his trust, I have to wear it.

“You know about Japan,” he says. “What else do you know about the world?”

I will not tell him about my father’s atlas, which my brother and I hid with our valuables in a locked trunk. Someone like Linden has no need to lock anything precious, except for his brides. He would not understand the madness of poorer, more desperate places.

“Not much,” I say. And I feign ignorance as he begins to tell me about Europe, a tower clock called Big Ben (I remember the image of it glowing at twilight amidst a London crowd), and extinct flamingos whose necks were as long as their legs.