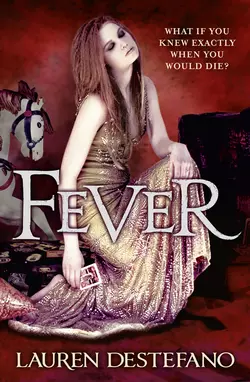

Fever

Lauren DeStefano

For 17-year-old Rhine Ellery, a daring escape from a suffocating polygamous marriage is only the beginning…Running away brings Rhine and Gabriel right into a trap, in the form of a twisted carnival whose ringmistress keeps watch over a menagerie of girls. Just as Rhine uncovers what plans await her, her fortune turns again. With Gabriel at her side, Rhine travels through an environment as grim as the one she left a year ago – surroundings that mirror her own feelings of fear and hopelessness.The two are determined to get to Manhattan, to relative safety with Rhine’s twin brother, Rowan. But the road there is long and perilous – and in a world where young women only live to age twenty and young men die at twenty-five, time is precious. Worse still, they can’t seem to elude Rhine’s father-in-law, Vaughn, who is determined to bring Rhine back to the mansion…by any means necessary.In the sequel to Lauren DeStefano’s harrowing Wither, Rhine must decide if freedom is worth the price – now that she has more to lose than ever.

Contents

Cover (#ulink_11df2203-4a07-579e-acc7-e93c8002f0ce)

Title Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Lauren DeStefano

Copyright

About the Publisher

the ocean clinging to our frozen skin.

I laugh, and Gabriel looks at me like I’m crazy, and we’re both out of breath, but I’m able to say, “We made it,” over the sound of distant sirens. Seagulls circle over us impassively. The sun is melting down into the horizon, setting it ablaze. I look back once, long enough to see men pulling our escape boat to shore. They’ll be expecting passengers, but all they’ll find are the empty wrappers from the packaged sweets we ate from the boat owner’s stash. We abandoned ship before we reached the shore, and we felt for each other in the water and held our breath and hurried away from the commotion.

Our footprints emerge from the ocean, like ghosts are roaming the beach. I like that. We are the ghosts of sunken countries. We were once explorers when the world was full, in a past life, and now we’re back from the dead.

We come to a mound of rocks that forms a natural barrier between the beach and the city, and we collapse in its shadows. From where we’re huddled we can hear men shouting commands to one another.

“There must have been a sensor that tripped the alarm when we got close to shore,” I say. I should have known that stealing the boat had been too easy. I’ve set enough traps in my own home to know that people like to protect what’s theirs.

“What happens if they catch us?” Gabriel says.

“They don’t care about us,” I say. “Someone paid a lot of money to make sure that boat is returned to them, I bet.”

My parents used to tell me stories about people who wore uniforms and kept order in the world. I barely believed those stories. How can a few uniforms possibly keep a whole world in order? Now there are only the private detectives who are employed by the wealthy to locate stolen property, and security guards who keep the wives trapped at luxurious parties. And the Gatherers, of course, who patrol the streets for girls to sell.

I collapse against the sand, faceup. Gabriel takes my shivering hand in both of his. “You’re bleeding,” he says.

“Look.” I cast my head skyward. “You can already see the stars coming through.”

He looks; the setting sun lights up his face, making his eyes brighter than I’ve ever seen, but he still looks worried. Growing up in the mansion has left him permanently burdened. “It’s okay,” I tell him, and pull him down beside me. “Just lie with me and look at the sky for a while.”

“You’re bleeding,” he insists. His bottom lip is trembling.

“I’ll live.”

He holds up my hand, enclosed in both of his. Blood is dripping down our wrists in bizarre little river lines. I must have sliced my palm on a rock as we crawled to shore. I roll up my sleeve so that the blood doesn’t ruin the white cabled sweater that Deirdre knitted for me. The yarn is inlaid with diamonds and pearls—the very last of my housewife riches.

Well, those and my wedding ring.

A breeze rolls up from the water, and I realize at once how numb the cold air and wet clothes have made me. We should find someplace to stay, but where? I sit up and take in our surroundings. There’s sand and rocks for several more yards, but beyond that I can see the shadows of buildings. A lone freight truck lumbers down a faraway road, and I think soon it’ll be dark enough for Gatherer vans to start patrolling the area with their lights off. This would be the perfect place for them to hunt; there don’t appear to be any streetlights, and the alleyways between those buildings could be full of scarlet district girls.

Gabriel, of course, is more concerned about the blood. He’s trying to wrap my palm with a piece of seaweed, and the salt is burning the wound. I just need a minute to take this all in, and then I’ll worry about the cut. This time yesterday I was a House Governor’s bride. I had sister wives. At the end of my life, my body would have ended up with the wives who’d died before me, on a rolling cart in my father-in-law’s basement, for him to do only he knows what.

But now there’s the smell of salt, sound of the ocean. There’s a hermit crab making its way up a sand dune. And something else, too. My brother, Rowan, is somewhere out here. And there’s nothing stopping me from getting home to him.

I thought the freedom would excite me, and it does, but there’s terror, too. A steady march of what-ifs making their way through all of my deliciously attainable hopes.

What if he’s not there?

What if something goes wrong?

What if Vaughn finds you?

What if …

“What are those lights?” Gabriel asks. I look where he’s pointing and see it too, a giant wheel of lights spinning lazily in the distance.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” I say.

“Well, someone must be over there. Come on.”

He pulls me to my feet and tugs my bleeding hand, but I stop him. “We can’t just go wandering off into lights. You don’t know what’s over there.”

“What’s the plan, then?” he asks.

The plan? The plan was only to escape. Accomplished. And now the plan is to reach my brother, a thought I romanticized over the sullen months of my marriage. He became almost a figment of my imagination, a fantasy, and the thought that I’ll be reunited with him soon makes me light-headed with joy.

I had thought we could at least make it to land dry, and during the daylight, but we ran out of fuel. And we’re losing daylight by the second; it’s not any safer here than anywhere else, and at least there are lights over there, eerie as they may be, spinning like that. “Okay,” I say. “We’ll check it out.”

The impromptu seaweed wrap seems to have staunched the bleeding. It’s so carefully tied that it’s amusing, and Gabriel asks what I’m smiling about as we walk. He is dripping wet and plastered with sand. His normally neat brown hair is in tangles. Yet he still seems to be searching for order, some logical course of action. “It’s going to be okay, you know,” I tell him.

He squeezes my good hand.

The January air is in a fury, kicking up sand and howling through my drenched hair. The streets are full of trash, something rustling in a mound of it, and a single flickering streetlight has come on. Gabriel wraps his arm around me, and I’m not sure which of us he means to comfort, but my stomach is churning with the early comings of fear.

What if a gray van comes lumbering down that dark road?

There are no houses nearby—just a brick building that was maybe once a fire department half a century ago, with broken and boarded windows. And a few other crumbling things that are too dark for me to make out. I could swear that things are moving in the alleys.

“Everything looks so abandoned,” Gabriel says.

“Funny, isn’t it?” I say. “Scientists were so determined to fix us, and when we all started dying, they just left us here to rot, and the world around us too.”

Gabriel makes a face that could be perceived as disdain or pity. He has spent most of his life in a mansion, where he may have been a servant, but at least things were well-constructed, clean, and reasonably safe. If you avoided the basement, that is. This dilapidated world must be a shock.

The circle of light in the distance is surrounded by bizarre music, something hollow and brassy masquerading as cheerful. “Maybe we should go back,” Gabriel says when we get to the chain-link fence surrounding it. Beyond the fence I can see tents illuminated by candlelight.

“Go back to what?” I say. I’m shivering so hard, I can barely get the words out.

Gabriel opens his mouth to speak, but the words are lost by my own scream, because someone is grabbing my arm and pulling me through an opening in the fence.

All I can think is, Not again, not like this, and then my wound is bleeding again and my fist is hurting because I’ve just hit someone. I’m still hitting when Gabriel pulls me away, and we try to run, but we’re being overpowered. More figures are coming out of the tents and grabbing our arms, waists, legs, even my throat. I can feel the skin bunching under my nails, and someone’s skull crashing against mine, and then I’m dizzy, but some otherworldly thing keeps me violently moving in my own defense. Gabriel is yelling my name, telling me to fight, but it doesn’t do any good. We’re being dragged toward that spinning circle of light, where an old woman is laughing, and the music doesn’t stop.

Gabriel lands a perfect punch that sends one of the men crashing backward onto the dirt, but then there are others grabbing his arms and kneeing him from all sides.

“Who do you work for?” The old woman’s voice is calm. Smoke billows out of her mouth and from a stick held in her fingers. “Who sent you to spy on me?” She’s a first generation, short and stocky, with gray hair arranged in a bun encrusted with gaudy glass rubies and emeralds. Rose, who over the years had been showered by our husband, Linden, with trinkets and gems, would laugh at this cheap jewelry—the oversize pearls hanging from the woman’s chicken-skin neck; the silver bangles, rusted and peeling, that run up to her forearm; the ruby ring as big as an egg.

The men are holding Gabriel up by his arms, and he’s struggling to stay on his feet, when another man hits him. A boy, really; he can’t be any older than Cecily.

“Nobody sent us,” Gabriel says. I can see in his eyes that he’s not entirely here right now. He took the worst from our assailants, and I’m worried he might have a concussion. He takes another punch, this one to the ribs, and it sends him to his knees. My stomach lurches.

One of the men has got me by the throat, and two others by the arms, and all of them are smaller than me. It’s so difficult to see them as boys, even though that’s what they are.

Gabriel’s eyes are closing and then jolting open; his breath escapes in fluttery astonished gasps. My heart is pounding in my ears; I want to go to him, but the only thing that reaches him is my frustrated whimper. This is all my fault. I was supposed to be able to protect him; this is my world. I should have had a plan. I mutter something indignant and snap, “He’s telling the truth; we’re not spies.” Who would spy on a place like this?

Filthy girls are peeking out from a slit in the rainbow-striped tent, blinking like bugs. And I know immediately that this must be a scarlet district—a prostitution den of unwanted girls that Gatherers couldn’t sell to House Governors, or who simply had nowhere else to go.

“You shut up,” one of the men—boys—says into my ear. The old woman cackles and clatters with fake jewels that are like big glass insects and infectious boils on her fingers and wrists.

“Bring her into the light,” the old woman says. They drag me into the rainbow-striped tent below a ceiling of swaying lanterns, and the bug-girls scatter. The old woman grabs my jaw and tilts my head for a better look. Then she hocks spit onto my cheek and smears it, clearing away some of the blood and sand. Her black, horrible eyes light up with joy, and she says, “Goldenrod. Yes, I think that’s what I’ll call you.” The smoke makes my eyes water. I want to spit back at her.

The girls in the tent moan their protest, and one of them raises her head. “Madame,” she says. Her eyes are languid and filmy. “It’s after sunset. It’s time.”

The old woman backhands her, and in that same calm voice she says, as she examines her jeweled fingers, “You do not tell me. I tell you.”

The girl sinks in with the others and disappears.

Gabriel spits a mouthful of blood. The boys tug him to his feet.

“Bring her into the red tent,” the old woman says. It doesn’t matter that I’ve slumped to a dead weight and refuse to move my legs; two of the boys have no trouble dragging me away.

This is it, I think. Gabriel is going to die, and this old woman intends to make me one of her prostitutes. I can only assume that’s what those girls in the rainbow tent are. All that trouble to escape, all Jenna’s efforts to help me, for less than one day of freedom before a new hell emerged.

The red tent is lit up by lanterns that hang from the low ceiling. One of the lanterns hits my head, and when the boys let go of me, I drop to the cold earth. “Don’t go anywhere,” one of the boys, who is about a foot shorter than me, says. He pulls back his moth-eaten coat to show me a gun holstered in the waist of his pants. The other boy laughs, and they leave. I can see their silhouettes taking shape outside the zippered doorway, hear their sneering laughter.

I scan the tent for another opening I can wriggle through, but it’s rooted into the ground, and much of it is bordered by furniture. Polished, ancient-looking bureaus and trunks with things like hissing dragons painted across the drawers, cherry blossoms, gazebos, black-haired women staring sullenly into the water.

Antiques from some Eastern country that’s long gone. Rose would like these things. She would have stories for what’s saddening the black-haired women, could chart a path among the cherry blossoms that would take her where she wanted to go. For a moment I think I see what she would—an infinite world.

“Now, then,” the old woman says, appearing from nowhere and pulling me into one of two chairs on either side of a table. “Let’s take a look at you.”

Smoke ribbons up from a long cigarette held in the old woman’s wrinkled fingers. She brings it to her lips for a breath, and smoke rolls through her mouth and nostrils when she speaks again. “You are not from this place. I would have noticed you.” Her eyes, made up to match her jewels, are on mine. I look away.

“Those eyes,” she says, leaning closer. “Are you malformed?”

“No,” I say, forcing myself not to sound angry, because there’s a boy with a gun outside, and Gabriel is still at this woman’s mercy. “And we’re not spies. I keep trying to tell you. We just took a wrong turn.”

“This whole place is a wrong turn, Goldenrod,” she says. “But tonight’s your lucky night. If you’re looking for a fancier district to do business in”—she flits her fingers dramatically, letting ashes fly—“you won’t find any for miles. I’ll take good care of you.”

My stomach turns. I don’t say a word, because if I open my mouth, I’m sure I’ll vomit all over this beautiful antique table.

“I am Madame Soleski,” the woman says. “But you call me Madame. Let me see that hand.” She reaches across for my wrist and then slaps my bleeding left hand onto the table. The seaweed bandage is still holding on, though it’s bunched from my fist and dripping with blood.

She raises my hand toward the lantern and gasps when she sees my wedding band. She’s probably never seen real jewelry before. She sets her cigarette on the edge of the table and takes my hand in both of hers, examining the vines etched into my wedding band, the blossoms that Linden often copied along his building designs when he was thinking of me. They were fictional, he said. No such flower blooms in this world.

I clench my fist again, worried she’ll try to steal the ring. Even if that marriage was a sham, this small piece of it belongs to me.

Madame Soleski admires it for a moment longer, then lets go of my hand. She rummages through one of her drawers and returns with gauze that looks like it’s been used, and a bottle of clear liquid. The liquid burns when she clears away the seaweed and pours it onto my wound. It bubbles and hisses angrily. She’s watching me for a reaction, but I won’t give her one. She dresses my palm with gauze expertly.

“You’ve messed up one of my boys,” she says. “He’ll have a black eye tomorrow.”

Not good enough. I still lost the fight.

Madame Soleski fingers the sleeve of my sweater, and I resist, but she digs her fingers into my bandaged wound. I don’t want her touching me. Not my wedding band, and not this sweater. I think of Deirdre’s small, capable hands making it for me; they were etched with bright blue veins—her soft skin the only indication of her youth. Those hands could turn bathwater to magic, or thread diamonds into her knitting. Precision was in everything she created. I think of her wide hazel eyes, the soft melody of her voice. I think of how I will never see her again.

“Leave the bandage put,” she says, picking up her cigarette and tapping away some ash. “Wouldn’t want to get an infection and lose that hand. You have such exquisite fingers.”

I can no longer see the outlines of the boys standing guard outside, but I hear them talking. The gun was much smaller than the shotgun my brother and I kept in the basement, but if I could get my hands on it, I could figure it out. But how quick would I be? Some of the others might have weapons too. And I can’t leave without Gabriel. It’s my fault that he’s even here.

“Don’t speak unless spoken to, huh, Goldenrod? I like that. This isn’t exactly a talking business.”

“I’m not a part of your business,” I say.

“No?” The old woman raises her penciled eyebrows. “You look as though you have been running from some other kind of business. I can offer you protection. This is my territory.”

Protection? I could laugh. I have sore ribs and a throbbing forehead that suggest otherwise right now. What I say is, “We got a little lost, but we’ll be on our way if you’d let us go. We have family waiting for us in North Carolina.”

The woman laughs and takes a languid breath through her cigarette, her bloodshot eyes never leaving mine.

“Nobody with a family finds their way here. Come, let me show you the pièce de résistance.” She says those last words with a practiced accent. Her cigarette has run out, and she stomps it with her high-heeled shoe, which appears to be a size too small.

She leads me outside, and the boys standing guard immediately stop their laughing as she passes. One of them tries to trip me with his foot, and I step around it.

“This is my kingdom, Goldenrod,” Madame says. “My carnival of amour. You wouldn’t know what ‘amour’ is, of course.”

“It’s ‘love,’” I answer, gratified when her eyebrows raise in surprise. Foreign languages are something of a lost art, but my brother and I had the rare advantage of parents who valued education. Even if we could never use it, even if we could never grow to be linguists or explorers, the knowledge filled our minds, brightened our daydreams. Sometimes we ran through the house, pretending we were parasailing high over the Aleutians, that later we’d sip green tea under the plum blossoms in Kyoto, and at night we squinted at the starry darkness and pretended we could see our neighboring planets. “Do you see Venus?” my brother said. “It’s a woman’s face, and her hair is on fire.” We were crammed in the open window, and I answered, “Yes, yes, I see it! And Mars is crawling with worms.”

Madame wraps her arm around my shoulders and squeezes. She smells like decay and smoke. “Ah, love. That’s what the world has lost. There’s no more love, only the illusion of it. And that’s what draws the men to my girls. That’s what it’s all about.”

“Which?” I say. “Love, or illusion?”

Madame chuckles, squeezes me again. I am reminded of the long walk I took with Vaughn through the golf course that one chilly afternoon, how his presence seemed to erase all the good in the world, how it felt like an anaconda was coiling around my chest. And all the while, Madame brings me to her spinning circle of light. What is it with first generations and their collection of breathtaking things? I hate myself for being intrigued.

“You know your français,” Madame says pertly. “But here is a word I bet you haven’t heard.” Her eyes widen with intensity. “Carnival.”

I know the word. My father tried to describe carnivals to my brother and me. Celebrations for when there was nothing to celebrate, he’d say. I could understand, but Rowan couldn’t, so the next day when we woke up, there were ribbons draped all over our bedroom, and a cake was waiting on our dresser with forks and cranberry seltzer, which was my favorite, but we almost never had any because it was so hard to find. And we didn’t go to school that day. My father played strange music on the piano, and we spent the day celebrating nothing at all, except maybe that we were all alive.

“This is what carnivals were all about,” Madame says. “They called it a Ferris wheel.”

Ferris wheel. The only thing in this whole wasteland of abandoned rides that isn’t rotting or rusted.

Now that I’m close enough to really look at it, I can see that the wheel is full of seats, and there’s a little staircase leading up to the lowest point. The chipped paint reads: ENTER HERE.

“It didn’t work when I found it, of course,” Madame goes on. “But my Jared is something of a genius with electrical things.”

I say nothing, but tilt my head to watch the seats spinning against the night sky. The wheel makes a rusted creaking groan as it goes, and for just a moment, I hear laughter in that eerie brass music.

My parents have looked up at Ferris wheels. They were a part of this lost world.

One of the boys is leaning on the railing surrounding the thing, and he eyes me warily. “Madame?” he says.

“Bring it to a stop,” she says.

A cold breeze swirls around me, and it’s ripe with antique melodies and the smell of rust and all of Madame’s strange foreign perfumes. An empty seat comes to a stop before the staircase where I stand. Madame’s bracelets clack and clatter as she lays her hand on my spine and presses me forward, saying, “Go on, go on.”

I don’t think I can stop myself. I climb the stairs, and the metal shudders beneath my feet and sends tremors up my legs. The seat rocks a little as I settle into it. Madame sits beside me and pulls the overhead bar down so that it locks us in. We start to move, and I’m breathless for an instant as we ascend forward and into the sky.

The earth gets farther and farther away. The tents look like bright round candies. The girls move about them, shadows.

I can’t help myself; I lean forward, astounded. This wheel is five, ten, fifteen times taller than the lighthouse I climbed in the hurricane. Higher even than the fence that kept me trapped as Linden’s bride.

“This is the tallest place in the world,” Madame says. “Taller than spy towers.”

I’ve never heard of a spy tower, but I doubt they’re taller than the factories and skyscrapers in Manhattan. Even this wheel couldn’t claim as much. Maybe, though, it’s the tallest place in Madame’s world. I could believe that.

And as we make our way toward stars that feel frighteningly attainable, I feel myself missing my twin. He was never one for whimsical things. Since our parents’ death, he’s stopped believing in things more fantastic than bricks and mortar, less horrific than ominous alleyways where girls become soulless and men pay for five minutes with their bodies. His every moment is consumed with survival—his and mine. But even my brother, who is all practicality, would have his breath taken away by this height, these lights, the clarity of this night sky.

Rowan. Even his name feels far away from me now.

“Look, look.” Madame points eagerly. Her girls are milling below in their dingy, exotic clothes. One of them twirls, and her skirt fills up with air, and her laughter echoes like hiccups. A man grabs her pale arm, and still she laughs, tripping and flailing as he drags her into a tent.

“You’ve never seen girls as beautiful as mine,” Madame says. But she’s wrong—I have. There was Jenna, with her gray eyes that always caught the light, her grace; she would swirl and hum through the hallways, her nose buried in a romance novel the whole time. The attendants blushed and averted their eyes, she so intimidated them with her confidence, her coy smiles. In a place like this she would have been a queen.

“They want a better life. They run away, come here to me. I deliver their babies, I cure their sniffles, I feed them, keep them clean, give them nice things for their hair. They come to this place asking for me.” She grins. “Maybe you’ve heard of me too. You’ve come here for my help.” She takes my left hand with a force that rocks our car. I tense, thinking we’ll capsize, but we don’t. We’ve stopped ascending now; we’re at the top. I look out over the side. There’s no way down, and the fear starts to set in. Madame controls this thing. If I wasn’t completely at her mercy before, I am now.

I force myself to stay calm. I won’t let her have the satisfaction of my panicking; it would only empower her.

My heart is thudding in my ears.

“That boy you came here with—he is not the one who gave you this beautiful wedding ring, is he.” It’s not a question. She tries to slide the ring from my finger, but I make a fist and draw away.

“Both of you show up like drowned rats,” she says. Her laughter creaks like the rusty gears that hold our car together. “But under that you are all sparkles and pearls. Real pearls.” She’s looking at my sweater. “And he is made up like a lowly attendant.”

I can’t deny any of this. She’s managed to sum up the last several months of my life perfectly.

“Running off with your attendant, Goldenrod, behind the back of the man who made you his wife? Did your husband force himself on you? Or maybe he couldn’t satisfy you, and so you met with that boy of yours in secret—in secret, late at night, rustling in your closet among your silk dresses like a pair of savages.”

My cheeks burn, but it’s not like the embarrassment I felt when my sister wives teased me about my lack of intimacy with Linden. This is sick and invasive. Wrong. And Madame’s smoky stench is making it hard to breathe. The height is making me dizzy. I close my eyes.

“It isn’t like that,” I say through gritted teeth.

“It’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Madame says, wrapping her arm around my shoulders. I catch the whimper before it leaves my throat. “You’re a woman, after all. Women are the fairer sex. And one as lovely as you—your husband must have turned into a beast around you. It’s no wonder you found yourself a sweeter boy. And this one is sweeter, isn’t he? I can see it in his eyes.”

“His eyes?” I splutter, furious. When I open my eyes, I focus on one of Madame’s gaudy hair gems so I don’t have to look at her or the ground. “Before your henchmen beat him half to death?”

“That’s another thing.” Madame tenderly brushes the hair from my face. I jerk back, but she doesn’t seem to care. “My men know how to protect my girls. It’s a rough world, Goldenrod. You need protection.”

She grabs my chin, and her fingers press against my jawbone until it hurts. She stares at my eyes. “Or maybe,” she sings, “your husband didn’t want to pass this defect of yours on to his children. Maybe he threw you out with the trash.”

Madame is a woman who loves to talk. And the more she says, the less accurate she becomes. I realize that she couldn’t read me as easily as she thought. She’s just probing through the options, hoping to get a rise out of me. I could lie to her and she wouldn’t know.

“I’m not malformed,” I say, feeling suddenly giddy about this small power I have over her. “My husband was.”

This makes Madame beam with intrigue. She releases my face and leans close. “Oh?”

“He might have turned into a beast around me, but it didn’t matter. Nine times out of ten, he couldn’t do anything about it. And like you said, women have needs.”

Madame bounces a little, rocking and creaking our car. It’s clear she gets off on the idea of young lust. I hardly have to continue the lie; she’s writing the rest of the story herself.

“And you were forced into the arms of your attendant.”

“In my closet, like you said.”

“Right under your husband’s nose?”

“In the very next room.”

She can have whatever deranged lie she wants. But the truth, like my wedding band, is something of mine that she can’t have.

The girls, hundreds of feet below, are a chorus of giggles. They all dance with the men for a while before disappearing into tents. And Madame’s henchmen sometimes peel the opening in the tent for a glimpse.

“Oh, Goldenrod, you are a gem.” She takes my face in her hands and kisses my cheek between the words. “A gem, a gem, an absolute gem! You and I will have great fun.”

Great.

In a second we’re orbiting backward. The music is louder the closer we come to the ground, and the girls sadder.

the tent, curled up so closely to the wall of the tent that its green tinges his skin. There’s a dingy blanket under him, and his shirt is gone.

Madame told me this is where I’ll rest tonight, while she figures out what to do with me. There’s a basin of water and some towels and soaps that look like they were hand-carved.

I wet a towel and dab at the red mark on Gabriel’s cheek. Tomorrow it will be just one of many bruises. He mutters something, draws a breath.

“Did I hurt you?” I say.

He shakes his head, nuzzles his face against the ground.

“Gabriel?” I whisper. “Wake up.” He doesn’t answer me this time, even when I turn him onto his back and wring cold water over his face. My heart is pounding with fear. “Gabriel. Look at me.”

He does, and his pupils are two small, startled dots in all that blue, and he’s scaring me. “What did they do to you?” I say. “What happened?”

“The purple girl,” he mumbles, smacking his lips and closing his eyes. “She had a … something.” He moves his arm as though in indication. And then he’s gone again. Shaking him does nothing.

“He’ll be out for a few hours.” One of the girls is standing at the tent’s entrance, a blanket bunched in her arms. “He seemed like he was in a lot of pain. I just gave him a little something to help. Here.” She offers me the blanket. “It’s fresh off the laundry line.”

She tries to help me cover him, but I shrug her away and snap, “You’ve helped enough, thanks. Whose fault is it that he was in pain to begin with?”

“Neither of you are from here,” the girl nonchalantly says, wringing a towel out over the basin. “Madame is very paranoid about spies. If I didn’t subdue him, she would have ordered the bodyguards to beat him unconscious. I was doing him a favor.” There’s no malice in the way she speaks. She hands me the wet towel, and she keeps a polite distance.

“What spies?” I ask, and gently rub away the sand and blood from Gabriel’s face and arms. I don’t like whatever is subduing him. He’s all I have in this terrible place, and he’s so far away.

“They don’t exist,” the girl says. “Most of what that woman says is nonsense. The opiates make her so paranoid.”

What have we stumbled into? At least this girl is not as nightmarish as the rest. Under all that makeup I can see the sympathy in her eyes that are two small dark stars in a nebula of green eyeliner. Her skin is dark. Her short hair is curled into glossy ringlets. And she, like everything here, carries that musty-sweet scent that radiates from everything Madame has touched.

“Why did he call you ‘the purple girl’?” I say.

“My name is Lilac,” she says, and indicates the light purple flowers on her faded dress, the strap of which keeps falling off her shoulder. “Ask for me if you need anything else, okay? I have to get back to work.”

She opens the tent flap, exposing the night sky and filling the tent with cold air and laughter, and the desperate grunts of men and the giggling of girls, and the steady rhythm of brass.

“This is my fault,” I whisper. I trace the line between Gabriel’s lips. “I’ll get us out of here. I promise.”

There’s salt crusted in my hair, and I feel so grimy that it’s tempting to climb into the basin to wash everything away. But whenever the bodyguards hear the water sloshing as I dip towels into it, they peer through the slit in the tent. Privacy is a lost practice in scarlet districts, I suppose. I settle for rolling up my sleeves and the legs of my jeans to wash as much as I can. Someone has laid out a silk dress for me—as green as this tent, with an orange dragon running up the side—but I don’t wear it.

I curl up beside Gabriel, fitting my arm around him. The soaps have left me with Madame’s strange scent, but he still smells of the ocean. I feel his skin moving under my fingers as he breathes, his muscles in constant, steady motion over his ribs. I close my eyes, pretend his is an ordinary sleep and that saying his name would bring him right back to me.

Time passes. Girls come and go. I pretend I am asleep and strain to hear what they’re whispering to each other. They say things I don’t understand. Angel’s blood. The new yellow. Dead greens. Men yell at them from a distance, and they go, their jewelry clattering like plastic shackles.

I feel myself falling asleep and try to fight it. But one minute I’m here, and the next I’m rocking on the glittering waves. One minute Gabriel is beside me, and then in the next, Linden is wrapping himself around me the way he did in sleep. He sobs in my ear and says his dead wife’s name, and I open my eyes. The hard dirt and thin blanket is an unwelcome change from the fluffy white comforter I was just hallucinating, and for a moment Gabriel seems strange. His bright brown hair nothing like Linden’s dark curls; his body thicker and less pale. I try rousing him again. No response.

I close my eyes, and this time I dream of snakes. Their hissing heads erupt from the dirt, and they coil around my ankles. They try to take off my shoes.

I wake in a panic. Lilac is kneeling at my feet, easing my socks off. “Didn’t mean to scare you,” she says. I feel like hours have passed, but I can see through the slit in the tent that it’s still nighttime.

“What are you doing?” My voice is hoarse. It’s so cold in this tent that I can see my own breath. I don’t know how these girls haven’t frozen to death in their flimsy dresses.

“These are soaked. You have to keep extremities warm, you know. You could get pneumonia.”

She’s right, I am freezing. She wraps my bare feet in towels. I watch her as she rummages through a small suitcase. Her curls are disheveled, her dress more rumpled. When she kneels by Gabriel this time, she’s got an array of things in a black handkerchief. She mixes powder and water in a spoon and takes a lighter to it until it bubbles, then draws it up into a syringe. Then she starts tying a strip of cloth around Gabriel’s arm above the elbow—which is something my parents used to do before administering emergency sedatives to hysterical lab patients—and that’s when I push her away. “Don’t.”

“It’s going to help him,” she says. “Keep him calm, keep you both out of trouble.”

I think of the warm toxins flowing through my blood after I was injured in the hurricane, how Vaughn threatened me and I couldn’t even muster the strength to open my eyes. How helpless and numb and terrified I was. I would rather have suffered the pain of my injuries, the broken bones, sprained limbs, stitched skin, than have been paralyzed.

“I don’t care,” I say. “You’re not giving him anything.”

She frowns. “Then, it’s going to be a rough night.”

I could laugh. “It already is.”

Lilac opens her mouth to say something else, but a noise at the tent’s entrance makes her turn her head. There’s a moment of fear in her eyes; maybe she thought it would be a man, but then she relaxes. “You know you’re supposed to stay hidden,” she says. “You want to piss Madame off?”

She’s talking to the child who has just crawled into the tent, not through the guarded entrance but through a small opening along the ground. Dark, stringy hair is covering her face. She moves more into the light, tilts her head to me, and her eyes are like marbled glass, so light they’re barely even the color blue—a startling contrast to her dark skin.

Lilac sets down the spoon and pushes the child back in the direction she came from, saying, “Hurry up. Get lost before we both get hell for it.”

The child goes, but not before pushing back and huffing indignantly through her nose.

Gabriel stirs, and I snap to attention. Lilac offers up the syringe again, gnawing her lip. I ignore it. “Gabriel?” My voice is very soft. I brush some hair from his face, and I realize how damp and clammy his forehead is. His face is splotchy with fever. His eyelashes flutter, but it’s like he can’t quite raise them.

Out in the night someone yelps in pain or maybe just aggravation, and Madame’s shrill voice cries, “Useless, filthy child!”

Lilac is on her feet the next instant, but she has left the syringe on the ground for me. “He’ll want it,” she tells me as she hurries for the exit. “He’ll need it.”

“Rhine?” Gabriel whispers. He’s the only one in this broken carnival who knows my name. He screamed it in the gale, pieces of Vaughn’s fake world whipping around us. He whispered it within the mansion’s walls, leaning close to me. He’s lured me from sleep that way, while my husband and sister wives slept before dawn. Always with such purpose, like it matters, like my name—like all of me—is a precious secret.

“Yes,” I say. “I’m right here.”

He doesn’t answer, and I think he’s lost consciousness again. I feel stranded, start to panic about him going back to that dark, unreachable place. But then he sucks in a hard breath and opens his eyes. His pupils are back to normal, no longer losing themselves in all that blue.

His teeth are chattering, and he’s stuttering and slurring when he asks, “What is this place?”

Not where, but what. “It doesn’t matter,” I say, blotting some sweat from his face with my sleeve. “I’m going to get us out of here.” We’re both lost here, but of the two of us I have a better understanding of the outside world. Surely I can figure something out.

He stares at me for a long while, shuddering from the cold and the aftereffects of whatever was in that first syringe. And then he says, “The guards were trying to take you away.”

“They took me,” I say. “They took both of us.”

I can see him fighting to stay awake. There’s a dark bruise forming on his cheek; his mouth is chapped and bleeding; he’s shaking so hard, I can feel it without touching him.

I wrap the blanket around him more snugly, trying to imitate the cocooning technique Cecily swaddled the baby with on a cold night. It was one of the few times she looked sure of what she was doing. “Rest,” I whisper. “I’ll be right here.”

He watches me for a long time, his eyes darting up and down the length of my face. I think he’s going to speak. I hope he will, even if it’s just to say this is all my fault, that he told me the world was dangerous. I don’t care. I just want him here with me. I want to hear his voice. But all he does is close his eyes, and then he’s gone again.

I manage a fitful sleep beside him, shivering, covered with only a damp towel so Gabriel can have all the covers. I dream of crisp bed linens; of sparkling gold champagne that warms my throat and stomach as it goes down; of category-three winds rattling the edges, revealing bits of darkness behind a shiny perfect world.

I’m ripped from sleep by a gurgling, retching sound that at first makes me think I’m at my oldest sister wife’s deathbed. But when I open my eyes, I see Gabriel doubled over in a far corner of our tent. The smell of vomit is not quite as overwhelming as all the smoke and perfume that keeps this place in a perpetual smog.

I hurry to his side, all earnest, heart pounding. And now that I’m close to him, I can smell and see the coppery blood coming from a gash between his shoulder blades; the skin tears as he tenses his muscles. I don’t remember there being any knives in the struggle, but we were ambushed so fast.

“Gabriel?” I touch his shoulder but can’t bring myself to look at the stuff he’s coughing up. When he’s finished, I offer him a rag, and he takes it, slumping back on his heels.

It seems stupid to ask if he’s all right, so I’m trying to get a good look at his eyes. Shades of purple are tiered under them, from dark to light. The cold is making clouds of his breath.

In the light of the swinging lantern, his own shadows dance behind his still form.

He says, “Where is this place?”

“We’re in a scarlet district along the coastline. They gave you something; I think it’s called angel’s blood.”

“It’s a sedative,” he says; his voice is slurred. He crawls back for the blanket and collapses facedown. “Housemaster Vaughn kept it in stock. Hospitals used to carry it, but they stopped because of the side effects.” He doesn’t resist as I position him onto his side and draw the blanket over him. He’s shivering. “Side effects?” I say.

“Hallucinations. Nightmares.”

I think of the warmth that spread through my veins after the hurricane, think of being unable to move; Vaughn only kept me conscious long enough to threaten me. And though I don’t remember it, Linden claimed I muttered horrible things while I dreamt.

“Can I do anything?” I say, tucking the blankets around his shoulders. “Are you thirsty?”

He reaches for me, and I let him draw me to his side. “I dreamt you’d drowned,” he says. “Our boat was burning and there was no shore.”

“Not possible,” I say. His lips are chapped and bloody against my forehead. “I’m an excellent swimmer.”

“It was dark,” he says. “All I could see was your hair, going under. I dove after you and realized I was chasing a jellyfish. You were nowhere.”

“I’ve been here,” I say. “You’re the one who’s been nowhere. I couldn’t wake you up.”

He raises the blanket like a wing, wrapping me inside with him. It’s warmer than I thought it would be, and I realize at once how much I’ve missed him while he’s been under. I close my eyes, breathe deep. But the smell of the ocean is gone from his skin. He smells like blood and Madame’s perfume, which lingers in the white soapy film that floats in all the water basins.

“Don’t leave me again,” I whisper. He doesn’t answer. I reposition myself in his arms and draw back to look at his face. His eyes are closed. “Gabriel?” I say.

“You’re dead,” he mumbles sleepily. “I watched you die”—his voice hitches with a yawn—“watched you die all those horrible deaths.”

“Wake up,” I tell him, and sit up, and pull the blankets away, hoping the sudden cold will shock him awake.

He opens his eyes, glossy like Jenna’s when she was dying. “They were cutting your throat,” he says. “You tried to scream, but you had no voice.”

“It’s not real,” I say. My heart is pounding with fear. My blood is cold. “You’re delirious. Look; I’m right here.” My fingers brush his neck, which is flush and warm. I remember when we kissed, Linden’s atlas between us; I remember the warm air of his little breaths on my tongue and chin and neck, the sudden draftiness when he drew back. Everything dissolved from around us in that moment, and I’d never felt so safe.

Now I worry that we’ll never be safe again. If we ever were.

The rest of the night is miserable. Gabriel succumbs to an unreachable sleep, and I fight to stay awake so I can keep watch against the dangers that lurk beyond our green tent.

When I sleep, I dream of smoke. Curling, twisting, weaving paths that lead nowhere.

“—up!” someone is saying. “Rise and shine, little love-bird! Réveille-toi!”

An arm tightens around me. I snap to attention. Madame is speaking in that phony accent again, her consonants flourishing like the smoke from her lips.

Daylight is a blinding force behind her, filling the silk outline of her scarves like rainbow lizard crests, making her face a shadow. And the whole tent is full of green, reflecting on my skin.

Sometime in the night Gabriel pulled me back into the blanket with him, and his arm is encircling my ribs. He buries his face in my hair, and I can feel the clamminess of his forehead. When I sit up, the movement doesn’t rouse him. He doesn’t regain consciousness at all.

The syringe. The syringe is no longer where Lilac left it.

Madame takes my hands and pulls me to my feet. She cups my face in her papery hands and smiles. “Even lovelier in the daylight, my Goldenrod.”

I’m not her Goldenrod. I’m not her anything. But she seems to have claimed me as one of her possessions, her antiques, her plastic gems.

I will Gabriel not to mutter my name again. I don’t want Madame to have it, rolling it off her tongue the way she fondled the flowers of my wedding band.

She pouts. “You do not want to wear the beautiful dress I laid out for you?” It hangs over her arm now like a deflated corpse, like the bloodless body of the girl who wore it last.

“Your sweater is so beautiful. How can you stand to wear it while it’s filthy?” she says sadly. I think her frown could melt right off her face. “One of the little ones will wash it for you.” Her accent has morphed to something else now. All of her THs come out like Zs, and her Ws like Vs. One of ze little ones vill vash it for you.

She thrusts the dress at me, and unwinds a fur stole from her shoulders and drapes it around my neck. “Change. I’ll wait for you outside. It’s a beautiful day!”

I’ll vait for you.

When she’s gone, I change quickly, figuring it’s my only way out of this tent. And I admit that the silk feels nice against my skin, and the stole, despite the choking must, is so warm I could get lost in it. Wearing these things may be the only way Madame lets me out of the tent, but what about Gabriel? Gabriel, who is still trapped in a haze. I kneel beside him and touch his forehead. I’m expecting it to be feverish, but it’s cold.

“I’ll get us out of here,” I say again. No matter that he can’t hear me; the words aren’t entirely for him.

Madame peels back the tent flap and tsk-tsks, snagging my wrist and tugging so hard, I think of the time my arm was dislocated and my brother had to snap it back into place. “Don’t worry about him,” she says. My bare feet are dragging, and I realize I’m not really trying to keep pace with her.

As we leave the tent, two small girls sweep past us and gather my rumpled clothes. Their heads are down, mouths tight. I only get a glimpse of them, but I think they’re twins. I’m pulled out into the cold sunshine, and the sky is a light candied blue, like I’m looking up through a sheet of ice. Madame fusses with my hair, which smells like a combination of salt water and a scarlet district. It feels heavy and tangled; her expression is distant, maybe disapproving, and I’m sure she’s going to criticize it, but she only says, “Don’t you worry about the boy.” She grins, and I swear I can see my outline repeated in each of her too-white teeth. “He’ll wake up when he can learn to be reasonable about sharing you.”

In the daylight, without the commotion or the light of the Ferris wheel, I can see what a wasteland this place is. Long stretches of just dirt, or a rusty piece of machinery erupting from the ground like it’s growing from a seed. There’s another ride off in the distance, and at first I think it’s a smaller Ferris wheel turned onto its side, but as we get closer, I can see metal horses inside of it, impaled by poles, their legs poised as though they were trying to escape before they were immobilized. Madame catches me staring and tells me it’s called a merry-go-round.

The black eyes of the horses fill me with pain. I want to break the spell on them, to animate the muscles in their legs and set them running free.

Madame brings me to the rainbow tent, the biggest and tallest of them all. Four of her boys are guarding it, their guns crossed at their chests like half an X. They don’t bother to look at me as Madame ushers me past, ruffling one of their heads.

She opens the tent flap, and a gust of cool air rolls in, unsettling the girls inside like wind chimes. They mutter and stir. Most of them are sleeping, piled against and atop one another.

The girls are all the same, like I’m looking into a house of mirrors. Long, bony limbs hunched against each other, and lipstick-smeared mouths full of rotted teeth. And for some girls it’s not lipstick—it’s blood. Unlit lanterns hang over their heads. The sun through the tent lights them up in oranges and greens and reds.

And farther down is the entryway to another tent that is veiled off by silk scarves trailing sickly sweet perfume, and something else. Decay and sweat. When Rose was dying, she concealed herself in powders and blush, but Jenna didn’t, and as I cared for Jenna during those final days, I could see her sallow skin beginning to bruise, and then the bruises would sink down to the bones and fester. It was a smell that haunted my dreams. My sister wife rotting from the inside out.

“I call this my greenhouse,” Madame says. “The girls sleep all day, so they can be fresh as daisies in the evening. Lazy girls.”

A few of the girls bother to look at me, blinking lazily and then returning to sleep.

She says she names the girls after colors, so she can keep track of them. Lilac is the only girl named for a color that is also a plant, because Jared, one of Madame’s best bodyguards, first found her lying unconscious in the lilac shrubs that border the vegetable gardens. “Belly about to burst,” Madame jokes, laughing maniacally. Lilac gave birth under a swinging lantern in the circus tent, surrounded by curious Reds and Blues. And the Greens, Jade and Celadon, who have since died of the virus.

“Nasty, useless little girl,” Madame Soleski says, indicating the little girl from last night with the strange eyes, who has crept out from a shadow. “One look at that shriveled leg and I knew on the day she was born that I’d never be able to get a decent price for her when she was the right age. But she can’t even be put to work! She scares the customers away. She bites them!”

Lilac, who is burrowed among the others, draws her daughter into her arms without opening her eyes. “Her name is Maddie,” she mutters, her voice slurred.

“Mad is right,” Madame Soleski says, nudging the child with her shoe. Maddie cants her head up at her with a violent stare. She snaps her little teeth at the old woman, venomous and defiant. “And she doesn’t speak!” Madame goes on. “Malformed. Horrible, horrible girl. She should be put down. Did you know that a hundred years ago when an animal was useless, they used to have a chemical that would put it to sleep forever?”

The smell of so many girls in such a small space is making me dizzy, and so are Madame’s words. One of the girls is twirling her hair, and it’s falling out in her hands.

A guard stands in the entryway. When nobody else is looking, I watch him reach into his pocket and then hold out a strawberry for Maddie. She pops it into her mouth, stem and all, a delicious secret she devours whole.

I hear a noise from the tent that’s veiled off. I think it’s a cough, or a groan. Either way, I don’t want to know. Madame is unfazed, and tightens her arm around my shoulders. I fight to keep my breathing even, but I want to cry out. I’m furious—maybe as furious as I was when I climbed out of the Gatherers’ van. I stood very still in a line with the other girls. I said nothing when I heard the first gunshot—the unwanted girls being murdered one at a time. There are so many of us, so many girls. The world wants us for our wombs or our bodies, or it doesn’t want us at all. It steals us, destroys us, piles us like dying cattle in circus tents and leaves us lying in filth and perfume until we’re wanted again.

I ran from that mansion because I wanted to be free. But there’s no such thing as free. There are only different and more horrible ways to be enslaved.

And I feel something I’ve never felt before. Anger at my parents for bringing my brother and me into this world. For leaving us to fend for ourselves.

Maddie stares at me, her eyes glassy and bizarre. This is the first time I’ve really looked at her. She’s obviously malformed—not just the strange, almost colorless blue of her eyes. In addition to her shriveled leg, one of her arms, the left, is shorter and much thinner than the other; her toes are almost nonexistent, as though something kept them from growing all the way out of her feet. But her face is angular and sharp, her expression all fearlessness and ire. It is the face of a girl who has seen the world, who realizes that it hates her, and who hates it in return.

Maybe that’s why she doesn’t speak. Why should she? What could she possibly have to say? She watches me, and then her eyes become distant, inaccessible, like she’s diving into waters too deep for me to follow her into.

Madame mutters something unkind and kicks the child in the shoulder, then she steers me outside.

There are plenty of other children, with stronger bodies and normal features. They work, polishing Madame’s fake jewels, doing laundry in metal basins and hanging it on wire that’s strung between dilapidated fences.

“My girls produce like jackrabbits.” Madame says the last word with malice. “Then they die and leave me to care for the mess they leave behind. But what can be done? The children make good workers at least.” Ze children.

Long ago President Guiltree did away with birth control. He’s of the pro-science mentality and thinks geneticists will fix the glitch in our DNA. In the meantime he feels it’s our responsibility to keep the human race alive. There are doctors who know how to terminate pregnancies, though they charge more than most can afford.

I wonder if my parents ever did it. For all the time they spent monitoring pregnancies, I’m sure they knew how to terminate one.

Abortions are supposed to be banned, but I’ve never heard of the president actually punishing anyone for disobeying one of his laws. I’m not entirely sure what the president even does. My brother says the presidency is a useless tradition that might have once served a purpose but has become nothing but formality—something to give us hope that order will be restored one day.

I hate President Guiltree, who has been in charge of this country longer than I’ve been alive. With his nine wives and fifteen children—all sons—he does not believe the end of humankind is near. He makes no move to stop the Gatherers from kidnapping brides, and encourages madmen like Vaughn to breed infants who will live their lives as experiments. Sometimes he’s on television, promoting new buildings or attending parties, flashing smiles, toasting his champagne glass at the TV like he expects us all to be celebrating with him. Or maybe he’s mocking us.

“He’s kind of handsome,” Cecily said once, when we were all watching TV and his face appeared in a commercial. Jenna said he looked like a child molester. We’d laughed about it then, but now that I’m in a scarlet district, Jenna’s former home, I think she must have been serious. Living in a place like this, she must have learned how to see all the monsters that can hide in a person.

Madame shows me her gardens, which are mostly patches of weeds and buds, encased in low wire fences. The strawberries, though, are growing under a weatherproof tarp. “You should see them in the spring sunshine,” she says giddily. “Strawberries and tomatoes and blueberries so fat they explode between your teeth.” I wonder where she gets the seeds. They’re so hard to come by in the city, where all of our fruits and vegetables seem to have taken on the city’s gray tinge.

She shows me the other tents, full of antique furniture, silk pillows piled on the dirt floors. Only the best for her customers, she says. The air in each of them is muggy with sweat. At the last tent, which is all pink, she turns to face me. She takes my hair from either side, in both hands, holding it out and watching the way it falls from her fingers. A strand gets caught on one of her rings, but I don’t flinch as it’s ripped from my scalp. “A girl like you is wasted as a bride.” She says the word like vasted. “A girl like you should have dozens of lovers.”

Her eyes are lost. She’s staring through me suddenly, and wherever she’s gone, it brings out the humanity in her. For the first time I can see her eyes under all that makeup, see that they’re brown and sad. And oddly familiar, though I’m sure I’ve never seen anyone like this woman in my life. I never even dared to peek into the shadows of scarlet districts nestled in alleyways back home.

I was never even curious.

Her lips curl into a smile, and it’s a kind smile. Her lipstick cracks, revealing a bleary pink underneath.

We’re standing by a heap of rusted scrap metal that is humming mechanically and emitting a faint yellow glow. One of Jared’s projects, I assume. Madame raves about his inventions. “Contraptions,” she calls them. “This will be a warming device for the soil. My Jared thinks it will make it easier to plant crops in the winter,” she tells me, patting one of the rusted pieces.

“So, what do you think of my carnival, chérie?” she asks. “The best in South Carolina.”

It amazes me how Madame can speak without the cigarette ever falling from the corner of her mouth. Maybe I’ve been breathing in too much of her smoke secondhand, but I’m in awe of her. Things fill with color as she moves past them. Her gardens grow. She created a strange dreamland with only the ghost of a dead society and some bits of broken machines.

She also never seems to sleep. Her girls are napping now that it’s daytime, and her bodyguards seem to alternate shifts, but she is forever weaving between tents, tilling, primping, barking orders. Even my dreams last night smelled of her.

“It’s not like any other place I’ve seen,” I admit, which is the truth. If Manhattan is reality, and the mansion a luxurious illusion, this place is a dilapidated, blurry line that divides the two places.

“You belong here,” she says. “Not with a husband. Not with a servant.” She wraps her arm around me, leading me through a patch of shriveled, snowy wildflowers. “Lovers are weapons, but love is a wound. That boy of yours,” she says, unaccented, “is a wound.”

“I never said I love him,” I say.

Madame smiles mischievously, her face flourishing with creases. It strikes me how the first generations are aging. Soon they’ll be gone. And no one will be left to know what old age looks like. Twenty-six and beyond will be a mystery.

“I’ve had many lovers,” she tells me. “But only one love. We had a child together. A beautiful little creature with hair that was every shade of yellow. Like yours.”

“What happened to them?” I ask, feeling brave. Madame has prodded and scrutinized me from the moment I arrived, and now, at last, she’s exposing her own weakness.

“Dead,” she says, picking up her accent again. The humanity vanishes from her eyes, leaving them reproachful and cold. “Murdered. Dead.”

She stops walking and tucks my hair behind my ears, tilts my chin, inspects my face. “And I am to blame for the pain. I should not have loved my daughter as I did. Not in this world in which nothing lives for long. You children are flies. You are roses. You multiply and die.”

I open my mouth, but no words come. What she says is horrible and true.

And then I wonder, does my brother think of me this way? We entered this world together, one after the other, beats in a pulse. But I will be first to leave it. That’s what I’ve been promised. When we were children, did he dare to imagine an empty space beside him where I then stood giggling, blowing soap bubbles through my fingers?

When I die, will he be sorry that he loved me? Sorry that we were twins?

Maybe he already is.

The tip of Madame’s cigarette flares red as she breathes deep. Lilac says the smoke makes her delusional, but I wonder how much of what Madame says is truth. “You are to be loved in moments. Illusions. That’s what I provide to my customers,” she says. “Your boy is greedy.”

Gabriel. When I left him, his dry lips were muttering silently. I noticed the stubble growing on his chin; he’d been re-dressed in his attendant’s shirt, which was ripped where the bodyguards had pulled at him. I was worried for the purple skin around his eyes, his raspy breaths.

“He loves you too much,” Madame says. “He loves you even in sleep.”

We walk through the strawberry patch, Madame prattling incessantly about the amazing Jared and his underground device that keeps the soil warm, simulating springtime so that her gardens can grow. “The most magical part,” she says, “is that it keeps the ground warm for the girls and for my customers.”

As she goes on, I think of what she said about Gabriel, about him loving me too much, but mostly about how he is a wound. Vaughn thought the same thing of Jenna; she served him no purpose, bore him no grandchildren, showed his son no real love, and she died for it.

It’s important to be useful in this world. The first generations seem to all agree about that.

“He’s a strong worker,” I say, interrupting her tangent about summer mosquitoes. “He can lift heavy things, and cook, and do just about anything.”

“But I cannot trust him,” Madame says. “What do I know about him? He was dropped at my feet as if from the sky.”

“But you are trusting me,” I say. “You’re telling me all of these things.”

She squeezes my shoulders, giggling like a bizarre and maniacal child. “I trust no one,” she says. “I am not trusting you. I am preparing you.”

“Preparing me?” I say.

As we walk, she rests her head on my shoulder, and her warm breath makes the hair on the back of my neck rise. The smoke from her cigarette is choking, and I suppress coughs.

“I do the best I can for my girls, but they are weary. Used up. You are perfect. I have been thinking, and I will not hand you over to my customers so they can reduce your value.”

Reduce my value. My stomach twists.

“Rather,” Madame says, “I think I could make more money off you if you remain pristine. We shall have to find a place for you. Dancing, maybe.” I can feel her smile without seeing her face. “Letting them have a taste. Letting them be hypnotized.”

I can’t follow the dark path her thoughts have taken, and I blurt out, “What about the boy I came with, then? If I’m doing all of this for your business”—the word gets caught on my tongue—“then I need to know that he’s okay. There needs to be a place for him.”

“Very well,” Madame says, suddenly bored. “It’s a small enough request. If he proves to be a spy, I will have him killed. Be sure to tell him that.”

By evening Madame sends me back to the green tent. I think it might have belonged to Jade and Celadon before the virus overtook them. She says one of her girls will be in to see me soon.

Gabriel is still out of it, and there’s a child holding his head in her lap. One of the blond twins I saw earlier.

“Please don’t be mad; I know I shouldn’t be here,” she says, not looking up. “He was making such awful noises. I didn’t want him to be alone.”

“What noises?” I ask, my voice gentle. I kneel beside him, and his skin is paler than before. There’s a rash of red across his cheeks and throat, and the skin around his bruise is fiery orange.

“Sick-person noises,” she whispers. Her hair is very blond. Her eyelashes are the same color, fluttering up and down like wisps of light. She’s running her small hands through his hair and across his face. “Did he give you that ring?” she asks me, nodding at my hand.

I don’t answer. I dip a towel into the basin, wring it out, and dab at Gabriel’s face with it. This feeling is horrible and familiar—watching someone I care for suffer, and having nothing but water to help them with.

“Someday I’ll have a ring that’s made of real gold too,” the girl says. “Someday I’ll be first wife. I know it. I have birthing hips.”

I’d laugh under less dire circumstances. “I knew a girl who grew up wanting to be a bride too,” I say.

She looks at me, and her green eyes are wide and intense. And for a second I think maybe this girl is right. She will grow up to be passionate and spirited; she will stand out in a line of dreary Gathered girls; a man will choose her, and come to her bed flushed with desire.

“Did she?” the girl asks. “Become a bride, I mean.”

“She was my sister wife,” I say. “And yes, she was given a gold ring too.”

The girl smiles, revealing a missing front tooth. Pale brown freckles dot her nose and spill into her cheeks like a blush.

“I bet she was pretty,” the girl says.

“She was. Is,” I correct myself. Cecily is gone from me, but she’s still alive. I can’t believe I almost forgot. It seems like forever ago that I left her screaming my name in a snowbank. I ran, didn’t look back, angrier with her than I’d ever been with anyone in my life.

The memory is a lifetime away from this smoky, dizzying place. I don’t even feel angry anymore. I don’t feel much of anything at all.

“How’s the patient?” Lilac says from the doorway. The girl whips to attention, and her expression turns sheepish. She’s been officially caught. She eases Gabriel’s head from her lap and hurries off, muttering apologies, calling herself a stupid girl.

“It’s her job to tend to the sickroom,” Lilac says. “She can’t resist a Prince Charming in distress.”

In the daylight, without makeup, Lilac is still a creature of beauty. Her eyes are sultry and sad, her smile languid, her hair messy and stiff on one side. Her skin, as dark as her eyes, is cloaked in gauzy blue scarves. Snow is flurrying around behind her.

She says, “Don’t worry. Your prince will be fine. Just a little sedated is all.”

“What have you given him?” I say, not hiding my anger.

“It’s just a little angel’s blood. The same stuff we take to help us sleep.”

“Sleep?” I growl. “He’s comatose.”

“Madame is wary of new boys,” Lilac says, not without compassion. She kneels beside me and presses her fingers to Gabriel’s throat. She’s silent as she monitors his pulse. Then she says, “She thinks they’re spies coming to take away her girls.”

“Yet she lets anyone with money come in and have their way with them.”

“Under strict supervision,” Lilac says pointedly. “If anyone tries something funny—and sometimes they do …” She makes a gun shape with her hands, points at me, shoots. “There’s a big incinerator behind the Ferris wheel where she burns the bodies. Jared rigged it from some old machinery.”

It’s not surprising. Cremation is the most popular way to dispose of bodies. We’re dropping off so quickly, there’s not even room to bury all of us, and there are some rumors that the virus contaminates the soil. And just as there are Gatherers to steal girls, there are cleaning crews who scoop up the discarded bodies from the side of the road and haul them to the city incinerators.

The thought makes me ache. I can feel Rowan, for just a moment actually feel him, looking for my body, worrying that I’ve already withered to ash. When the dust is heavy as he passes the incineration facilities, does he fear it’s me he’s breathing in? Bone or brain, or my eyes that are identical to his?

“You’re looking a little pale,” Lilac says. How can she tell? Everything in this tent is tinted green. “Don’t worry; we won’t be doing anything strenuous tonight.”

I don’t want to do anything but sit here with Gabriel, to protect him from another debilitating injection. But I know I have to play by the rules of Madame’s world if I hope to escape it. I’ve done it all before, I tell myself, and I can do it again. Trust is the strongest weapon.

Lilac smiles at me. It is a tired, pretty smile. “We’ll start with your hair, I think. It could stand to be washed. Then we’ll figure out a color scheme for your makeup. Your face makes a nice canvas. Has anyone ever told you that? You should see the messes I’ve had to work with before. The noses on some of these girls.”

I think of Deirdre, my little domestic, who called my face a canvas too. She was a wonder with colors; sometimes I would let her do my makeup if I was bored. Sensible earth tones for dinners with my husband; wild pinks and reds and whites when the roses were in bloom; blue and green and frosty silver when my hair was drenched with pool water and I sat in my bathrobe, reeking of chlorine.

“What is my makeup for?” I ask, though my stomach is twisting with dread.

“It’s just practice for now,” Lilac says. “We’ll do a few trials, show them to Her Highness.” She says the last two words without affection. “And whenever she approves a color scheme, we can begin training you.”

“Training me?”

Lilac straightens her back, pushing out her chest and mock-primping her hair; it pools between her fingers like liquid chocolate. She mimics Madame’s fake accent. “In the art of seduction, darling.” Ze art of zeduction.

Madame wants me to be one of her girls. She still wants to sell me to her customers, even if it’s not in the traditional sense.

I look at Gabriel. His lips have tightened. Can he hear what’s happening? Wake up! I want him to rescue me, the way he did in the hurricane. I want him to carry us both away. But I know he can’t. I’ve caused all of this, and now I’m on my own.

that droop down from the ceiling, so low our heads almost touch it as we stand before the mirror. The air is heavy with smoke; I’ve been exposed to it for so long now that my senses are not as offended. Lilac twists my hair into dozens of little braids and douses them with water, “to bring out the curls.”

Outside, the brass music has begun. Maddie is sitting at the entrance, peeking out into the night. I follow her gaze and catch the smooth white of a thigh, wisp of a dress. There are desperate, shuddering grunts and gasps. Lilac giggles as she smears lipstick onto my mouth. “That’s one of the Reds,” she says, “probably Scarlet. She wants the whole world to know she’s a whore.” She straightens her back, yells the word “Whore!” out into the night; it flies over Maddie, who is stuffing her mouth full of semi-rotten strawberries and watching. The girl outside yips and howls with laughter.

I want to ask why Lilac is okay with her daughter watching what’s going on out there, but I remember the teasing I got from my sister wives. They would undress while I was in the room, run into the hallway in their underwear and ask to borrow each other’s things. Late in her pregnancy Cecily didn’t even bother with the buttons of her nightgown, and her stomach floated in front of her everywhere. I guess being raised in such close quarters with so many other girls leaves no room for shyness.

And here, I am supposed to blend in. I can’t be shy. If Madame finds out that I lied about my torrid affairs, she won’t believe anything else about me. And so I act unfazed as Lilac explains Madame’s color-sorting system for her girls.

The Reds are Madame’s favorites: Scarlet and Coral have been with her since they were babies, and she lets them borrow her costume jewels. She lets them take hot baths and gives them the ripest strawberries from another little garden she grows behind the tent, because their bright eyes and long hair fetch the highest prices.

The Blues are her mysterious ones: Iris and Indigo and Sapphire and Sky. They cling to one another when they sleep, and they giggle at the things they whisper among themselves. But their teeth are murky and mostly missing, and they only get chosen by the men unwilling to pay for more, and they’re never in the back room for long. Men take them hurriedly, sometimes standing up, against trees, or even in the tent with all the others there to see.

There are more girls. More colors that blend together into one muddy mess as Lilac talks about them, pausing to ask Maddie to hand her the peroxide. Maddie, fingers and mouth stained red with strawberry juice, crawls (she hardly walks, I’ve noticed) to the assortment of jars and bottles and vials. She finds the one that’s labeled peroxide and offers it up.

“How did she know which bottle was the right one?” I say.

“She read it.” Lilac tilts the bottle onto a cloth, wipes some of the blush from my cheeks. “She’s very smart. ’Course, Her Highness”—again, said with malice—“likes to keep her hidden, thinks she’s just a useless malfie.”

“Malfie” is an unkind term for the genetically malformed. Sometimes women would give birth to malformed babies in the lab where my parents worked—children born blind, or deaf, or with any of an array of disfigurements. But more common were the children with strange eyes, who never spoke or reached the milestones the other children did, and whose behavior never synced with any genetic research. My mother once told me about a malformed boy who spent the nights wailing in terror over imaginary ghosts. And before my brother and I were born, our parents had a set of malformed twins; they had the same heterochromatic eyes—brown and blue—but they were blind, and they never spoke, and despite my parents’ best efforts they didn’t live past five years.

Malformed children are put to death in orphanages, because they’re considered leeches with no hope of ever caring for themselves. That’s if they don’t die on their own. But in labs they’re the perfect candidates for genetic analysis because nobody really knows what makes them tick.

“Madame said she bites the customers,” I say.

Lilac, holding an eyeliner pencil close to my face, throws her head back and laughs. The laugh mingles with the grunts and the brass and Madame shouting an order to one of her boys.

“Good,” she says.

In the distance Madame starts bellowing for Lilac, who rolls her eyes and grunts. “Drunk,” she mumbles, and licks her thumb and uses it to smudge the eyeliner on my eyelids. “I’ll be back. Don’t go anywhere.”

As if I could. I can hear the gun rattling in the guard’s holster just outside the entrance.

“Lilac!” Madame’s accented voice is slurred. “Where are you? Stupid girl.”

Lilac hurries off, muttering obscenities. Maddie follows her out, taking the bucket of semi-rotted strawberries with her.

I lie back on the bubblegum pink sheet that’s covering the ground and rest my head on one of the many throw pillows. This one is framed with orange beads. I think the smoke is to blame for my fatigue. I’m so tired here. My arms and legs feel so heavy. The colors, though, are twice as bright. The music twice as loud. The giggling, moaning, gasping girls are a music of their own. And I think there’s something magical about it all. Something that lures Madame’s customers in like fishermen to a lighthouse gleam. But it’s terrifying, too. Terrifying to be a girl in this place. Terrifying to be a girl in this world.

My eyes close. I wrap my arms around the pillow. I’m dressed in only a gold satin slip (gold has become Madame’s official color for her Goldenrod), but despite the winds outside, it’s warm in the tent. I suppose this is from the lingering smoke, and Jared’s underground heating system, and all the candles in the lanterns. Madame has truly thought of everything. To have her girls bundled in winter gear would hardly make them appealing to customers.

I’m eerily comfortable in this warmth. A nap seems incredibly inviting.

Don’t forget how you got here. Jenna’s voice. Don’t forget.

She and I are lying beside each other, surrounded by canopy netting. She’s not dead. Not while she’s tucked safely in my dreams.

Don’t forget.

I squeeze my eyelids down tight. I don’t want to think about the horrible way my oldest sister wife died. Her skin bruising and decaying. Her eyes glossing over. I just want to pretend she’s okay—just for a little longer.

But I can’t stave off the feeling that Jenna is trying to warn me to not be so comfortable in this dangerous place. I can smell the medicine and the decay of her deathbed. It gets stronger the more I feel myself fading to sleep.

The curtain swishes, clattering the beads that frame the entrance, and I snap to attention.

Gabriel is here, clear-eyed and standing on solid feet, dressed in a heavy black turtleneck and jeans and knit socks. The type of clothes Madame’s guards wear.

For a long moment we just stare at each other as if we’ve been apart for ages, which maybe we have. He has been beyond reach with angel’s blood since our arrival, and I have been whisked away by Madame at her every free moment.

I ask, “How are you feeling?” at the same time he says, “You look—”

I sit up in the sea of throw pillows, and he sits beside me, and the lanterns show me the deep bags under his eyes. When I left him this morning, Madame gave Lilac strict instructions to stop the angel’s blood, but he was sleeping, his mouth moving to make words I couldn’t understand. Now, at least, there’s color in his cheeks. His cheeks are flushed, actually. It’s especially warm in this tent, with all the incense sticks Lilac ignited, and the hot, sugary-sweet smell of the candles in the lanterns.

“How are you feeling?” I ask again.

“All right,” he says. “For a few minutes I was seeing strange things, but that’s passed now.” His hands are trembling slightly, and I put my hands over them. His skin is a little clammy, but nothing like it was as he lay comatose and shivering beside me. Just the memory makes me cling to him.

“I’m so sorry,” I whisper. “I haven’t come up with a plan to get us out yet, but I’ve bought us some time, I think. Madame wants me to perform.”

“Perform?” Gabriel says.

“I don’t know—something about dancing, maybe. It could be worse.”