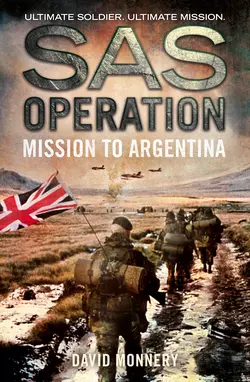

Mission to Argentina

David Monnery

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 288.34 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But can the SAS prevent the launch of Exocet missiles at the British Task Force?May 1982: as the British Task Force prepares to retake the Falkland Islands, a lone Sea King helicopter makes an apparently forced landing in the southernmost reaches of Chile.The only threat to the Task Force – and the enemy’s only hope of ultimate victory – is Argentina’s Super Etendard aircraft and their sea-skimming Exocet missiles. Since radar cannot be relied upon, the British must opt for a less conventional warning system. Before landing in Chile, the ‘stray’ Sea King drops a team of men into Argentina, where they are tasked with remaining hidden within sight of the airfields and within easy reach of the enemy’s security patrols.Getting the men in is easy enough, but staying unobserved is another matter – and eventual escape will be next to impossible…Mission to Argentina tells the electrifying story of this SAS operation from the inside – a heart-stopping thriller about the regiment equalled by no other: the SAS!