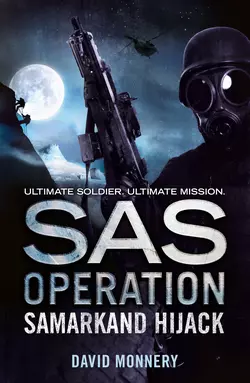

Samarkand Hijack

David Monnery

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But can the SAS storm a fortress prison held by Muslim terrorists to rescue a group of British tourists?In 1994, in the newly independent state of Uzbekistan, a party of mostly British tourists is on a day excursion from the fabled city of Samarkand when Muslim fundamentalists hijack their bus. Unknown to the hijackers, this particular group contains recently retired ex-SAS sergeant Jamie Docherty, and the rebellious daughter of the British Foreign Minister, already a tabloid favourite back home.Uncertain how to respond to the terrorists’ demands, the Uzbekistan government accepts a British offer of assistance: two members of the SAS crack Counter Revolutionary Warfare wing are dispatched to Samarkand, with instructions to liaise with the local ex-KGB unit.As the negotiations drag on, in the mountain fortress prison Docherty must call on all his formidable expertise and ingenuity to keep his fellow hostages alive, and to prepare them for a prospective rescue mission.The only force likely to have any chance of successfully penetrating the fortress and liberating the prisoners will be a group led by men of the legendary Special Air Service – the SAS!

Samarkand Hijack

DAVID MONNERY

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1995

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1995

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover photographs © Nik Keevil/Arcangel Images (soldier); MILpictures, Tom Weber/Getty Images (background); Shutterstock.com (textures)

David Monnery asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155339

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008155346

Version: 2015-11-02

Contents

Cover (#u94713304-241f-5ea5-addc-6ddd2ac2ea50)

Title Page (#ub964ac9a-57aa-525c-894d-fdd3a6693086)

Copyright (#u078dab98-b5ac-5aa4-b098-17148e30104f)

Prologue (#u1d581a5e-1924-5857-9367-06dae32f6dfc)

Chapter 1 (#u1687d403-5ca9-5a3f-a013-ad4ce1792ab6)

Chapter 2 (#u5122089f-07d8-5e9c-92b6-c0bdf38d2521)

Chapter 3 (#u01eac47c-011a-5f73-a4f8-2af82c6d2aba)

Chapter 4 (#u1482954f-9b45-5a37-9d76-81e55058ba26)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ue4f1ade8-500e-58c3-99a8-92ddd94173e4)

Bradford, England, 14 March 1979

It was a Wednesday evening, and Martin could hear the Coronation Street theme music through the wall. His mother was in the back room ready to watch, but he had not been allowed to join her, allegedly because he had homework to finish. The real reason, though, was that there was a sex scandal going on; one of the characters was sleeping with another’s wife, or something like that. His mother didn’t like any of her children watching such things, and certainly not Martin, who at twelve was the youngest of the three.

He continued drawing the blue border around the coastline of England with the felt-tip pen. He liked drawing maps, and he was good at it, both as a copyist and from memory. England, though, was always something of a challenge: it was so easy to make the fat peninsulas too thin and vice versa.

The coastline was finished, and he stopped for a moment. It was dark outside now, so he walked over to draw the curtains across the front windows. The sound of raucous laughter floated down the street; it was probably the youths with the motor bikes who habitually gathered outside the fish and chip shop. Thinking about the latter made Martin feel hungry, even though he’d only had supper an hour or so earlier. His father, brother and sister would be getting chips on their way home from the game, like they always did, but by the time they came through the front door the only thing left would be the smell on their hands.

It was no fun being the youngest. Still, next season he would be able to go with them to the evening games. His father had promised.

Martin stood by the table for a moment, wondering whether to ask his mother again whether he could watch TV with her. But she would only say no, and anyway he didn’t really want to – it was not being allowed that was so annoying.

He sat back down with his map, and started putting in red dots where all the First Division teams played. He had just put in the one for Norwich when there was a knock on the front door.

He hesitated in the doorway to the hall, but there was no sign of his mother coming out. It was probably only one of those political canvassers in any case, and Martin enjoyed telling them what he had once heard his father say: ‘A secret ballot should be just that!’

He walked towards the door, noticing the shadow through the leaded glass, and pulled it open.

Almost immediately a foot pushed it back, and Martin himself was propelled backwards into the hall. He had a momentary glimpse of a helmeted figure silhouetted against the starry sky, before something flew over his head and exploded into flames in the hall behind him.

It all happened so fast. ‘Burn, you Paki bastards!’ The words seemed to echo down the street as the attacker scrambled back down the path and disappeared into the darkness. Martin turned to find a sheet of flame where his mother’s wall hangings from home had been, and fire already spreading up the carpeted stairway. Then a sudden draught fanned the flames and he heard her scream.

He started forward, but the heat from the flames threw him back, the smell of singed hair in his nostrils. His mind told him his mother could get out of the window into the back garden, while his heart told him she needed him. But now the flames were forcing him back towards the front door, and he knew that to try to run through them would be suicide.

He backed into the front garden, and then spun round and raced next door, where he banged the polished iron knocker like a madman.

‘What the blazes…?’ Mr Castle said as he opened the door.

‘There’s a fire!’ Martin screamed at him. ‘Our house is on fire! Mum’s inside!’

Mr Castle advanced two steps down the path and saw the light from the flames dancing in the porch. ‘I’ll ring 999,’ he said, and disappeared back inside, leaving Martin in a paroxysm of indecision.

Then inspiration struck. He ran back out to the street, past their house and the other neighbour’s, to where the passage ran through to the allotments. At the end of his own garden he clambered over the rickety fence and ran to the back of the burning house. The kitchen door was closed, and so was the back room window. Inside there was nothing but fire.

In later years, the rest of the evening would come to seem like a blurred sequence of images – the sirens of the fire engines, the people gathered in the street, his father, brother and sister coming home, the policemen with their bored expressions and stupid questions. But that moment alone in the darkened garden would never lose its sharpness, with the windows full of flames and the dreadful truth they told.

1 (#ue4f1ade8-500e-58c3-99a8-92ddd94173e4)

They were standing on a dry, broken slope. There were no fragments of masonry to be seen, no shards of tile or pottery, but the configuration of the land, the angular ditches and the flattened hillocks all suggested human occupation.

‘This was the southern end of the original Afrasiab,’ Nasruddin Salih told the tour party, ‘which became Maracanda and eventually Samarkand. It was razed to the ground in 1220 by the army of Genghis Khan. Only a quarter of the population, about a hundred thousand people, survived. It was another one and a half centuries before Tamerlane revived the city and made it the centre of his empire. These buildings here’ – Nasruddin indicated the line of domed mausoleums which gracefully climbed the desolate hillside – ‘were probably the finest architectural achievement of Tamerlane’s time.’

‘Bloody incredible,’ Mike Copley murmured, holding up his exposure meter.

It was, Jamie Docherty thought. The blue domes rose out of the yellow-brown hill like articles of faith, like offerings to God which the donors knew were too beautiful to be refused.

‘“Shah-i-Zinda” means “The Living King”,’ Nasruddin was explaining. ‘This complex was built by Tamerlane to honour Qutham ibn Abbas, who was a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad, and one of the men most responsible for bringing Islam to this area. He was praying in a shady spot on this hill when a group of Zoroastrians attacked and beheaded him. Qutham finished his prayer’ – Nasruddin acknowledged the laughter with a slight smile – ‘picked up his head and jumped into a nearby well. He has lived there ever since, ready to defend Islam against its enemies.’

The guide smiled again, but there was something else in his expression, something which Docherty had noticed several times that morning. The British-born Pakistani had been with them since their departure from Heathrow six days before, and for the first few days of the tour had seemed all affability. But over the last twenty-four hours he had seemed increasingly under some sort of strain.

The tour party was moving away, down the path which led to the Shah-i-Zinda’s entrance gate. As usual, Charles Ogley was talking to – or rather at – Nasruddin. Probably telling the guide he’d made yet another historical mistake, Docherty thought sourly. The lecturer from Leeds seemed unable to last an hour without correcting someone about something. His lecturer wife Elizabeth was the most frequent recipient of such helpfulness, but seemed to thrive on it, using it to feed some reservoir of bitterness within her soul. They were not an attractive couple, Docherty had decided before the tour’s first day had ended. Fortunately they were the only two members of the party for whom he felt any dislike.

He banished the Ogleys from his mind, and focused his attention on the magical panorama laid out before him.

‘I think you take photographs with your eyes,’ his wife said, taking an arm and breaking into his reverie.

‘Aye,’ Docherty agreed. ‘It saves on film.’

Isabel smiled at the idea, and for the hundredth time felt pleased that they had come on this trip. She was enjoying it enormously herself, particularly since phoning the children and setting her mind at rest the night before. And he was loving it.

They caught up with the rest of the party at the foot of the hill, and waited by the archway which marked the entrance to the complex of buildings while Nasruddin arranged their collective ticket with the man in the booth. Then, their guide in the lead, the party started climbing the thirty-six steps which led up past one double-domed mausoleum towards the entrance gate of another.

‘This is called the “Stairway to Heaven”,’ Nasruddin said. ‘Pilgrims count each step, and if they lose count they have to start again at the bottom. Otherwise they won’t go to heaven.’

‘I wonder if this is where Led Zeppelin got the song title from,’ Mike Copley mused out loud.

‘Idiot,’ his wife Sharon said.

At the top of the stairway they passed through an archway and into the sunken alley which ran along between the mausoleums. Here the restoration work seemed to be only just beginning, and the domes were bare of tiles, the walls patchy, with swathes of mosaic giving way to expanses of underlying buff-coloured brick. At the end of the alley they gathered around the intricately carved elm door of Qutham’s shrine, and Nasruddin pointed out where the craftsman had signed his name and written the year, 1405. Inside, the Muslim saint’s multi-tiered cenotaph was a riot of floral and geometric design.

Docherty stood staring at it for several minutes, wondering why he always felt so moved by Islamic architecture. He had first fallen in love with the domes and mosaics in Oman, where he had served with the SAS during the latter years of the Dhofar rebellion. A near-fluency in Arabic had been one legacy of that experience, and in succeeding years he had managed to visit Morocco and Egypt. His final mission for the SAS, undertaken in the first weeks of the previous year, had taken him to Bosnia, and the wanton destruction of the country’s Islamic heritage had been one of several reasons offered by that war for giving up on the human race altogether.

Not to worry, he thought. After all, Qutham was down there in his well taking care of business.

He looked up to find that, once again, the tour party had left him behind. Docherty smiled to himself and walked back out into the shadowed courtyard, from where he could see the rest of the party strolling away down the sunken alley. Isabel, her black hair shining in the sun above the bright red dress, was talking to Sam Jennings. The silver-haired American didn’t walk that gracefully, but at seventy-five his mind was as young as anyone’s in the tour party. Both Docherty and Isabel had taken a liking to him and his wife Alice from the first day.

Their small bus was waiting for them outside the entrance. It had six double seats on one side, six single on the other, and a four-person seat at the back. Despite there being only fourteen in the party – fifteen counting Nasruddin – the four Bradford Pakistanis usually sat in a tightly bunched row on the rear seat, as if fearful of being contaminated by their infidel companions. This time though, one of the two boys – Imran, he thought – was sitting with Sarah Holcroft. Or Sarah Jones, to use the name she had adopted for this trip.

Docherty wondered if Imran had recognised her as the British Foreign Minister’s daughter. He hadn’t himself, though the girl had made no attempt to disguise her appearance, and her picture had been in the papers often enough. Isabel had, and so, if their behaviour was anything to go by, had both the Copleys and the Ogleys.

Brenda Walker, the social worker who usually sat with Sarah, was now sitting directly behind her. Docherty had his suspicions about Brenda, and very much doubted whether she was the social worker she claimed to be. He had come into fairly frequent contact with the intelligence services during his years in the army, and thought he knew an official minder when he saw one. But he hadn’t said anything to anyone else, not even Isabel. He might be wrong, and in any case, why spoil the generally good atmosphere that existed within the touring party? He wasn’t even sure whether Sarah herself was aware of her room-mate’s real identity.

‘Enjoying yourself?’ Isabel asked, leaning forward from her seat directly behind his, and putting her chin on his shoulder.

‘Never better,’ he said. ‘We seem to go from one wonder of the world to another.’

The driver started the bus, and they were soon driving back through the old city, up Tashkent Street and past the ruined Bibi Khanum mosque and the Registan assemblage of madrasahs, or Muslim colleges, both of which they had visited the previous afternoon. It was almost half-past twelve when they reached the cool lobby of the Hotel Samarkand. ‘Lunch will be in five minutes,’ Nasruddin told them, ‘and we shall be leaving for Shakhrisabz at one-thirty.’

While Isabel went up to their room Docherty bought a stamp and postcard from the post office on the ground floor and then took another look at the Afghan carpets in the hotel shop. They weren’t quite attractive enough to overcome his lifetime’s hatred of having something to carry.

In the largely empty dining-room fourteen places had been set on either side of a single long table. The four Bradford Pakistanis had already claimed the four seats at one end: as usual they were keeping as separate as civility allowed. The two older men flashed polite smiles at Docherty as he sat down in the middle of the other empty places.

On the first day he had made an effort to talk to them, and discovered that the two older men were brothers, the two younger ones their respective sons. Zahid was the family name, and the elder brother, Ali Zahid, was a priest, a mullah, attached to a mosque in Bradford. The younger brother, Nawaz, was a businessman of unspecified type, which perhaps accounted for the greater proportion of grey in his hair.

Ali’s son Imran and Nawaz’s son Javid were both about seventeen. Unlike their fathers they wore Western dress and spoke primarily in Yorkshire-accented English, at least with each other and the other members of the party. Both were strikingly good-looking, and the uneasy blend of respect and rebelliousness which characterized their relationship with their fathers reminded Docherty of his childhood in working-class Glasgow, way back in the fifties.

The two academics were the next to arrive, and took opposing seats at the other end of the table from the Zahids, without acknowledging either their or Docherty’s presence. The Ogleys had really fallen on hard times, Docherty thought. They had probably expected a party full of fellow academics, or at the very least fellow-members of the middle class. Instead they had found four Pakistanis, a Glaswegian ex-soldier and his Argentinian wife, a builder and his wife, and a bluntly spoken female social worker with a northern accent. Their only class allies turned out to be a cabinet minister’s daughter known for her sex and drug escapades, and elderly Americans who, it soon transpired, were veterans of the peace movement. The Ogleys, not surprisingly, had developed a bunker mentality by day two of the Central Asian Tours ‘Blue Domes’ package holiday.

Isabel came in next, now wearing a white T-shirt and baggy trousers. She was accompanied by Brenda Walker and Sarah Holcroft. The first had changed into a dress for the first time, and her attractively pugnacious face seemed somehow softened by the experience. The second had swept back her blonde hair, and fastened it with an elasticated circle of blue velvet at the nape of her neck. Even next to Isabel she looked lovely, Docherty thought. On grounds of political prejudice he had been more than ready to dislike a Tory cabinet minister’s daughter, but instead had found himself grudgingly taking a liking to the girl. And with a father like hers, Docherty supposed, anyone would need a few years of letting off steam.

The two Americans arrived at the same time as the soup. Sam Jennings was a retired doctor from a college town in upstate New York, and his wife Alice had had her hands full for thirty-five years raising their eleven children. The couple now had twenty-six grandchildren, and a continuing hunger for life which Docherty found wonderful. He had met a lot of Americans over the years, but these were definitely the nicest: they seemed to reflect the America of the movies – warm, generous, idealistic – rather than the real thing.

As usual, the Copleys were the last to arrive. Sharon had changed into a green backless dress, but Mike was still wearing the long shorts and baseball hat which made him look like an American in search of a barbecue. With his designer stubble head, goatee beard, stud earrings and permanently attached camera, he had not immediately endeared himself to Docherty, but here too first impressions had proved a worthless guide. The builder might seem like an English yobbo who had strayed abroad by accident, but he had a smile and a kind word for everyone, and of all the party he was the most at ease when it came to talking with the locals, be they wizened women or street urchins. He had a wide-eyed approach to the world which was not that common among men in their late thirties. And he was funny too.

For most of the time his wife seemed content to exist in his shadow. Isabel had talked with her about their respective children, and thought her nice enough, but Sharon Copley, unlike her husband, had rarely volunteered any opinions in Docherty’s hearing. The only thing he knew for certain about her was that she had brought three suitcases on the trip, which seemed more than a trifle excessive.

After announcing an hour’s break for lunch, Nasruddin Salih had slipped back out of the hotel, turned left outside the doors and walked swiftly up the narrow street towards the roundabout which marked the northern end of Maxim Gorky Boulevard. A couple of hundred metres down the wide avenue, in the twenty-metre-wide strip of park which ran between its two lanes, he reached the bank of four public telephones.

The two at either end were in use, one by a blonde Russian woman in jeans and T-shirt, the other by an Uzbek man in a white shirt and a tyubeteyka embroidered skullcap. In the adjoining children’s play area two Tajik children were contesting possession of a ball with their volume controls set on maximum.

Nasruddin walked a few more metres past the telephones and sat down on a convenient bench to wait. He was sweating profusely, he realized, and maybe not just from the heat. Still, it was hot, and more than once that morning he had envied Mike Copley his ridiculous shorts.

The Uzbek had finished his call. Nasruddin got up and walked swiftly across to the available phone. The Russian woman was telling someone about an experience the night before, alternating breathless revelations with peals of laughter. These people had no sense of shame, Nasruddin thought.

He dialled the first number.

Talib answered almost instantly. ‘Yes?’ the Uzbek asked.

‘There are no problems,’ Nasruddin told him.

‘God be praised,’ Talib said, and hung up.

Nasruddin heard footsteps behind him, and turned, slower than his nerves wished. It was only the Tajik boy’s father, come to collect their ball, which had rolled to within a few feet of the telephones. Nasruddin smiled at him, waited until the man had retrieved the ball, and then turned back to dial the other number. The Russian woman was now facing in his direction, nipples pressing against the tight T-shirt, still absorbed in her conversation.

He dialled and turned away from her. This time the phone rang several times before it was picked up, each ring heightening Nasruddin’s nervousness.

‘Sayriddin?’ he asked, struggling to keep the anger out of his voice.

‘Assalamu alaikam, Nasruddin…’

‘Yes, yes. You are ready? You know what to do?’ Though if he didn’t by this time, then God would surely abandon them…

‘Of course. I deliver the message this evening, one hour after I hear from Talib. On Thursday morning I check Voice of the People. If there is nothing there I try again the next day. When I see it, then I call you at the number you gave me.’

‘Good. God be with you.’

‘And you, brother.’

Nasruddin hung up, and noticed that the Russian woman had gone. In her place was a young Uzbek, no more than seventeen by the look of him. He was wearing a sharp suit with three pens prominent in the top pocket. It sounded as if he was trying to sell someone a second-hand tractor.

Nasruddin looked at his watch. It was still only ten to one – time to get back to the hotel and have some lunch. But he didn’t feel hungry. Nor did he fancy small talk with the members of the party.

He sat down again on the bench, and watched the world go by. The uneasy blend of Asian and European which was Samarkand still felt nothing like home to him, even though one side of his family had roots in the town which went back almost a century. A great-great-grandfather had originally come as a trader, encouraged by the bloody peace the English had imposed on Afghanistan in the late nineteenth century. Nasruddin’s side of the family had come to England instead, much later, in the mid 1950s. He himself had been born in Bradford in 1966, heard about his relatives in far-off Samarkand as a young adolescent, and had determined even then to visit them if ever the chance arose.

And here he was.

Two Uzbek women were walking towards him, both clothed head to foot in the Muslim paranca, eyes glinting behind the horsehair mesh which covered their faces. There was something so graceful about them, something so beautiful. Nasruddin turned his eyes away, and found himself remembering the pictures in Playboy which he and the others had studied so intently in the toilets at school. He watched the two women walking away, their bodies swaying in the loose black garments. When English friends had argued with him about such things he had never felt certain in his heart of the rightness of his views. But at this moment he did.

Not that it mattered. He had always been certain that the other way, the Western way, the obsession with sex, could never work. It had brought only grief in its wake – broken families, prostitution, rape, sexual abuse, AIDS…the list was endless. Whatever God expected of humanity, it was not that. In the words of one of his favourite songs as a teenager, that was the road to nowhere.

And whatever befell him and the others over the next few days, he had no doubt that they were on the right road.

He made his way slowly back to the hotel, arriving in time to supervise the boarding of the tour bus for the two-hour ride to Shakhrisabz. He watched with amusement as they all claimed the same places they had occupied that morning and the previous afternoon, and idly wondered what would happen to anyone daring enough to claim someone else’s.

Now that the dice were cast he felt, somewhat to his surprise and much to his relief, rather less nervous than he had.

Docherty also registered the guide’s change of mood, but let it slip from his mind as the views unfolding through the bus window claimed more and more of his attention. They were soon out of Samarkand, driving down a straight, metalled road between cherry orchards. Groups of men were gathered in the shade, often seated on the bed-like platforms called kravats.

‘Do you think they’re waiting for the cherries to ripen?’ Docherty asked Isabel.

‘I doubt it,’ she said. ‘The women probably do all the picking.’

‘Aye, but someone has to supervise them,’ Docherty argued.

She pinched the back of his neck.

The orchards soon disappeared, giving way to parched fields of grain. As the road slowly rose towards the mountains they could see the valley of the Zerafshan behind them, a receding strip of vegetation running from east to west in a yellow-brown sea, the domes of Samarkand like blue map pins in the green swathe.

‘What do you know about Shakhrisabz?’ Isabel asked.

‘Not a lot,’ Docherty said. ‘It was Tamerlane’s home town – that’s about all.’

‘There’s the ruins of his palace,’ Mike Copley volunteered, open guide book in his lap. ‘It says the only thing left is part of the entrance arch, but that that’s awesome enough.’

‘The son of a bitch didn’t do anything by halves,’ Sam Jennings commented. ‘I was reading in this’ – he held up the paperback biography – ‘about his war with the Ottoman Turks. Do you want to hear the story?’ he asked, with the boyish enthusiasm which seemed to make light of his years.

‘Go on, educate us,’ Copley told him.

‘Well, the Ottoman Turks’ leader Bayazid was just about to take Constantinople when a messenger from Tamerlane arrives on horseback. The message, basically, says that Tamerlane is the ruler of the world, and he wants Bayazid to recognize the fact. Bayazid has heard of Tamerlane, but thinks he’s just another upstart warlord. His guys, on the other hand, are the military flavour of the month. The whole of Europe’s wetting itself in anticipation, so he can hardly believe some desert bandit’s going to give him any trouble. He sends back a message telling Tamerlane to go procreate himself.

‘A few weeks later the news arrives that Tamerlane’s army is halfway across Turkey. Bayazid’s cheesed, but realizes he has to take time out to deal with the upstart, and he leads his two hundred thousand crack troops across Anatolia to meet Tamerlane. When the armies are a few miles apart the Turks get themselves in formation and wait. At which point Tamerlane’s army hits them from every conceivable side. A few hours later Bayazid is on his way to Samarkand in a cage. And the Turkish conquest of Constantinople gets put back fifty years, which probably saves the rest of Europe from Islam.’

The American smiled in pleasure at his story.

‘I think it’s a shame the way someone like Tamerlane gets glorified,’ his wife said. ‘In Samarkand he’s becoming the new Lenin – there are statues everywhere. The man turned cities into mountains of skulls, for God’s sake. He can’t be the only hero the Uzbeks have in their past.’

‘He wasn’t an Uzbek,’ Charles Ogley said, his irritable voice floating back from the front seat. ‘None of the Uzbeks’ heroes are. Nawaii, Naqshband, Avicenna. The Uzbeks didn’t get here until the end of the fifteenth century.’

Docherty, Mike Copley and Sam Jennings exchanged glances.

‘So who was here before them, Professor?’ Copley asked.

‘Mostly other Turkic peoples, some Mongols, probably a few Arabs, even some Chinese. A mixture.’

‘Maybe countries should learn to do without heroes,’ Sarah Holcroft said, almost defiantly.

‘Sounds good to me,’ Alice Jennings said.

Ogley’s grunt didn’t sound like agreement.

There were few signs of vegetation now, and fewer signs of farming. A lone donkey tied to a roadside fence brayed at them as they went past. The mountains rose like a wall in front of the bus.

The next hour offered a ride to remember, as the bus clambered up one side of the mountain range to the six-thousand-foot Tashtakaracha Pass, and then gingerly wound its way down the other. On their left were tantalizing glimpses of higher snow-capped ranges.

‘China’s on the other side of that lot,’ Copley observed.

They arrived at Shakhrisabz soon after three-thirty. ‘The name means “green city”,’ Nasruddin told them, and it did seem beautifully luxuriant after the desert and bare mountains. The bus deposited them in a car park, which turned out to occupy only a small part of the site of Tamerlane’s intended home away from home, the Ak Saray Palace. It would have been bigger than Hampden Park, Docherty decided.

As Copley’s book had said, all that remained of the edifice was a section of wall and archway. The latter, covered in blue, white and gold mosaics, loomed forty metres into the blue sky. Awesome was the word.

The other sights – another blue-domed mosque, a couple of mausoleums, a covered market – all paled in comparison. At around five-thirty, with the light beginning to take on a golden tinge, they stopped for a drink at the Ak Saray café. ‘We’ll leave for Samarkand in twenty minutes,’ Nasruddin said, before disappearing back outside.

The tourists sipped their mint tea and watched the sun sliding down over the western desert horizon. As the jagged-edged tower of Tamerlane’s gateway darkened against the yellow sky Docherty felt at peace with the world.

He smiled across the table at Isabel. Twelve years now, he thought, twelve years of the sort of happiness he hadn’t expected to find anywhere, let alone behind enemy lines in Argentina during the Falklands War.

It was an incredible story. At the beginning of the war Isabel, an exiled opponent of the Junta living in London, had agreed to return home as a spy, her love of country outweighed by hatred of its political masters. Docherty had been the leader of one of the two SAS patrols dropped on the mainland to monitor take-offs from the Argentinian airfields, and the two of them had ended up escaping together across the Andes into Chile, already lovers and more than halfway to being in love. Since then they’d married and had two children, Ricardo and Marie, who were spending these ten days with Docherty’s elder sister in Glasgow.

Isabel had made and mostly abandoned a career in compiling and writing travel guides, while Docherty had stayed on in the SAS until the early winter of 1992. Pulled out of retirement for the Bosnian mission a month later, his second goodbye to the Regiment in January 1993 had been final. Now, eighteen months later, the couple were preparing to move to Chile, where she had the offer of a job.

Chile, of course, was a long way from anywhere, and they had decided to undertake this Central Asian trip while they still could. It hadn’t been cheap, but it wasn’t that expensive either, considering the distances involved. The collapse of the Soviet Union had presumably opened the way for young entrepreneurs to compete in this market. Men like Nasruddin, Docherty thought, and idly wondered where their tour operator and guide had got to.

Nasruddin had crossed the road to the car park, and walked across to where two cars, a Volga and a rusting Soviet-made Fiat, were parked side by side under a large mulberry tree. There was no one in the cars, but behind them, in the circle of shade offered by the tree, six men were sitting cross-legged in a rough circle. Four of them were dressed modern Uzbek-style in cotton shirts, cotton trousers and embroidered skullcaps, but the other two were wearing the more traditional ankle-length robes and turbans.

As Nasruddin appeared the men’s faces jerked guiltily towards him, as if they were a bunch of schoolboys caught playing cards behind the bicycle sheds. Recognition eased the faces somewhat, but the tension in the group was still palpable.

‘Everything is going as expected,’ Nasruddin told them, squatting down and looking across the circle at Talib Khamidov. His cousin gave him a tight smile in return, which did little to soften the lines of his hawkish face.

‘They all came?’ Akbar Makhamov asked anxiously, ‘the Americans too?’ Despite Nasruddin’s assurances the others had feared that the two septuagenarians would sit out the side-trip to Shakhrisabz.

‘Yes. I told you they would come.’

‘God is with us,’ Makhamov muttered. The bearded Tajik was the other third of the group’s unofficial ruling triumvirate. He came from a rich Samarkand family, and like many such youths in the Muslim world, had not been disowned by his father for demonstrating a youthful excess of religious zeal. His family had not objected to his studying in Iran for several years, and on his return in 1992 Akbar had been given the prodigal son treatment. Over the last year, however, his father’s patience had begun wearing a little thin, though nothing like as thin as it would have done had he known the family money was being spent on second-hand AK47s and walkie-talkies for a mass kidnapping.

‘Everyone knows their duties?’ Nasruddin asked, looking round the circle.

They all did.

‘God be with us,’ Nasruddin murmured, getting to his feet. He caught Talib’s eyes once more, and took strength from the determination that he saw there.

He walked back to the tour bus, and found the driver behind his wheel, smoking a cigarette and reading one of the newly popular ‘romantic’ graphic novels. Nasruddin was angered by both activities, but managed to restrain himself from sounding it.

‘I told you not to smoke in the bus,’ he said mildly.

Muran gave him one contemptuous glance, and tossed the cigarette out through his window.

‘We’ll be picking up two more passengers on the way back,’ he told the driver. ‘A couple of cousins of mine. Just on the other side of Kitab. I’ll tell you when we get there.’

Muran shrugged his agreement.

Nasruddin started back for the café, looking at his watch. It was almost six o’clock. As he approached the tables the Fiat drove out of the car park and turned up the road towards Samarkand, leaving a cloud of dust hanging above the crossroads.

The group was ready to go, and he shepherded them back across the car park and into the bus, wondering as he did so which of them might make trouble when the time came. The ex-soldier and the builder looked tough enough, but neither seemed the sort to panic and do something stupid. Ogley was too fond of himself to take a risk, and the American was too old. Though neither he nor his wife, Nasruddin both thought and hoped, seemed the type to drop dead with shock.

Muran started up the bus, and Nasruddin sat down in the front folding seat. Once out on the road he sat staring ahead, half listening to the murmur of conversation behind him, trying to keep calm. He could feel a palpitation in his upper arm, and his heart seemed to be beating loud enough for everyone in the bus to hear.

He glanced sideways at the driver. There was a good chance the man would take the hundred American dollars and make himself scarce. But even if Muran went to the authorities, it wouldn’t matter much.

Nasruddin took a deep breath. Only ten minutes more, he told himself. It was almost dark now, and the fields to left and right were black against the sky’s vestigial light. Ahead of them the bus’s headlamps laid a moving carpet of light on the asphalt road. In the wing mirror he had occasional glimpses of the lights of the following car.

They entered the small town of Kitab, and passed families sitting outside their houses enjoying the evening breeze. In the centre a bustling café spilled its light across the road, and the smell of pilaff floated through the bus.

Nasruddin concentrated on the road ahead as they drove out through the northern edge of the town. A hundred metres past the last house he saw the figures waiting by the side of the road.

‘Just up here,’ he told Muran.

Docherty’s head had begun to drop the moment they started the return journey, but the jerk of the bus as it came to a halt woke him up. His eyes opened to see two men climbing aboard, each with a Kalashnikov AK47 cradled in his arms. A pistol had also appeared in Nasruddin’s hand.

The three men seemed to get caught up in one another’s movements in the confined space at the front of the bus, but this almost farcical confusion was only momentary, and all three guns were squarely pointed in the passengers’ direction before anyone had time to react.

A variety of noises emanated from the passengers, ranging from cries of alarm through gasps of surprise to a voice murmuring ‘shit’, which Docherty recognized as his own.

2 (#ue4f1ade8-500e-58c3-99a8-92ddd94173e4)

A stunned silence had settled on the tour party.

‘Mr and Mrs Ogley,’ Nasruddin said politely, ‘please move to the empty seats in the back.’

The academics stared at him for a moment, as if unable to take in the instruction. Nasruddin nodded at them, like a teacher trying to encourage a child, and they responded with alacrity, moving back down the aisle of the bus as if their lives depended on it. Elizabeth sat down next to Brenda Walker, while Charles took the single seat across the aisle from her.

Docherty was examining the two men holding the assault rifles. Both were in their late twenties or early thirties, and both, to judge by the slight body movements each kept making, were more than a little nervous. One wore a thin, dark-grey jacket over a white collarless shirt, an Uzbek four-sided cap and black trousers. His hair was of medium length and he was clean-shaven. Dark, sunken eyes peered out from either side of a hooked nose. His companion was dressed in a black shirt and black trousers, and wore nothing on his head. His hair was shorter, his Mongoloid face decorated with a neat beard and moustache.

‘I don’t suppose I need to tell you all that you have been taken hostage,’ Nasruddin begun. Then, as if realizing that he was still talking to them like a tour guide, the voice hardened. ‘You will probably remain in captivity for several days. Provided you obey our orders quickly and without question, no harm will come to any of you…’

There was something decidedly unreal about being taken hostage in Central Asia by a Pakistani with a Yorkshire accent, Docherty thought.

‘We do not wish to harm anyone,’ Nasruddin said, ‘but we will not hesitate to take any action that is necessary for the success of this operation.’ He looked at his captive audience, conscious of the giant step he had taken but somehow unable to take it in. It felt more like a movie than real life, and for a second he wondered if he was dreaming it all.

‘Can I ask a question?’ Mike Copley asked.

‘Yes,’ Nasruddin said, unable to think of a good reason for saying no.

‘Who are you people, and what do you want?’

‘We belong to an organization called The Trumpet of God, and we have certain demands to make of the Uzbekistan government.’

‘Which are?’

Nasruddin smiled. ‘No more questions,’ he said.

‘Can we talk to each other?’ Mike Copley asked.

The bearded hijacker spoke sharply to Nasruddin – in Tajik, Docherty thought, though he wasn’t sure. Their guide smiled and said something reassuring back. Docherty guessed that neither of the new arrivals spoke English.

‘You can talk to the people next to you,’ Nasruddin announced, deciding that conversation would do no harm, and that enforcing silence might be interpreted as a sign of weakness. ‘But no meetings,’ he added. He turned to Talib and Akbar, and explained his decision in Uzbek.

‘So what shall we talk about?’ Isabel asked Docherty in Spanish. She sounded calm enough, but he could hear the edge of tension beneath the matter-of-fact surface.

‘Some ground rules,’ he said in the same language. The two of them were used to conversing in her mother tongue, and at home often found themselves slipping between Spanish and English without thinking about it.

‘OK,’ she agreed. ‘Number one – you don’t try playing the hero. You’re retired.’

‘Agreed. Number two – don’t you try arguing politics with them. These don’t strike me as the kind of lads who like being out-pointed by women.’

‘That doesn’t make them very unusual,’ she said, putting her eyes to the window. ‘Where do you think they’re taking us?’

‘Somewhere remote.’ Docherty was watching Nasruddin out of the corner of his eye, thinking that he would never have suspected the man of pulling a stunt like this. He suddenly remembered something his friend Liam had said the last time he’d seen him, that the more desperate the times, the harder it was to recognize desperation.

He turned his attention back to his wife’s question. They seemed to be travelling mostly uphill, and the road was nowhere near as smooth as they were used to. He tried to remember the map of Central Asia he had examined before the trip, but the details had slipped from his mind. There were mountains to the east of the desert, and Chinese desert to the east of the mountains. Which wasn’t very helpful.

He thought about leaning across the aisle and asking to borrow Mike Copley’s guide book, but decided that would only draw attention to its existence and his own curiosity. Better to wait until they reached their destination, wherever that might be.

He turned round to look at Isabel, and found her angrily wiping away a tear. ‘I was just thinking about the children,’ she said defiantly.

He took her hand and grasped it tightly. ‘It’s going to work out OK,’ he said. ‘We’re going to grow old together.’

She smiled in spite of herself. ‘I hope so.’

Diq Sayriddin plucked a group of sour cherries from the branch above the kravat, and shared them out between the juice-stained hands of his friends. ‘I have to go inside for a while,’ he told them.

It was fifty-five minutes since he had received the call from Shakhrisabz at the public telephone in Registan Street. Nasruddin had expected him to make his own call from there, but somehow the place seemed too exposed. He had decided to use his initiative instead.

Sayriddin passed through the family house and out the back, climbed over the wall and walked swiftly down the alley which led to Tashkent Street. His father, as always, was sitting outside the shop in the shade, more interested in talking with the other shopkeepers than worrying about prospective customers. Sayriddin slipped round the side of the building and let himself in through the back door.

The whole building was empty – no one stayed indoors at this hour of the day – and the office was more or less soundproof, but just to be on the safe side he wedged the door shut with a heavy roll of carpet. Exactly an hour had now gone by since the call from Talib – it was time to make his own.

He pulled the piece of paper with the number, name and message typed on it from his back pocket, smoothed it out and placed it on the desk beside the telephone. He felt more excited than nervous, but perhaps they were the same thing.

After listening for several seconds to make sure he was alone, he picked up the receiver and dialled the Tashkent number. It rang once, twice, three times…

‘Hello,’ an irritable voice said.

‘I must speak with Colonel Muratov,’ Sayriddin said. His voice didn’t sound as nervous as he had expected it would.

‘This is Muratov. Who are you?’

‘I have a message for you…’ Sayriddin began.

‘Who are you?’ Muratov repeated.

‘I cannot say. I have a message, that is all. It is important,’ he added, fearful that the National Security Service chief would hang up.

There was a moment’s silence at the other end, followed by what sounded like a woman speaking angrily.

‘What is this message?’ Muratov asked, almost sarcastically.

‘The Trumpet of God group…’ Sayriddin began reading.

‘The what?!’

‘The Trumpet of God group has seized a party of Western tourists in Samarkand,’ Sayriddin said, the words tumbling out in a single breath. ‘They were with the “Blue Domes” tour, staying at the Hotel Samarkand. There are twelve English and two Americans among the hostages…’

Muratov listened, wondering whether this was a hoax, or simply one of his own men winding him up. Or maybe even one of the Russians who had been jettisoned when the KGB became the NSS. It didn’t sound like a Russian though, or a hoax.

‘Who the fuck are The Trumpet of God?’ he asked belligerently.

‘I cannot answer questions,’ Sayriddin said. ‘There is only the message.’

‘OK, give me the message,’ Muratov said. Who did the bastard think he was – Muhammad?

‘There are eight men and six women,’ Sayriddin continued. ‘All will be released unharmed if our demands are met. These will be relayed to you, on this number, at eleven o’clock tomorrow morning. Finally, The Trumpet of God does not wish this matter publicized. Nor, it believes, will the government. News of a tourist hijacking will do damage to the country’s tourist industry, and probably result in the cancellation of the Anglo-American development deal’ – Sayriddin stumbled over this phrase and repeated it – ‘the Anglo-American development deal…which is due to be signed by the various Foreign Ministers this coming Saturday…’

Whoever the bastards were, Muratov thought, they were certainly well informed. And the man at the other end of the line was probably exactly what he claimed to be, just a messenger.

‘Is that all clear?’ Sayriddin asked.

‘Yes,’ Muratov agreed. ‘How did you get my private number?’ he asked innocently. His answer was the click of disconnection.

In the office of the carpet shop Sayriddin was also wondering how Nasruddin had got hold of such a number. But his second cousin was a resourceful man.

He placed the roll of carpet back up against the wall, and let himself out through the back door.

In the apartment on what had, until recently, been Leningrad Street, Bakhtar Muratov sat for a moment on the side of the bed, replaying in his mind what he had just heard. He was a tall man for an Uzbek, broadly built with dark eyes under greying hair, and a mat of darker hair across his chest and abdomen. He was naked.

His latest girlfriend had also been undressed when the phone first rang, but now she emerged from the adjoining bathroom wearing tights and high-heeled shoes.

‘I’m going,’ she said, as if expecting him to demand that she stay.

‘Good,’ he said, not even bothering to look round. ‘I have business to deal with.’

‘When will I see you again?’ she asked.

He turned his head to look at her. ‘I’ll call you,’ he said. Why did he always lust after women whose tits were bigger than their brains? he asked himself. ‘Now get dressed,’ he told her, and reached for his discarded clothes.

Once she had left he walked downstairs, and out along the temporarily nameless street to the NSS building a hundred metres further down. The socialist slogan above the door was still in place, either because no one dared take it down or because it was so much a part of the façade that no one else noticed it any more.

Muratov walked quickly up the stairs to his office on the first floor and closed the door behind him. He looked up the number of the Samarkand bureau chief and dialled it, then sat back, his eyes on the picture of Yakov Peters which hung on the wall he was facing.

‘Samarkand NSS,’ a voice answered.

‘This is Muratov in Tashkent. I want to speak to Colonel Zhakidov.’

‘He has gone home, sir.’

‘When?’

‘About ten minutes ago,’ the Samarkand man said tentatively.

The bastard took the afternoon off, Muratov guessed. ‘I want him to call me at this number’ – he read it out slowly – ‘within the next half hour.’

He hung up the phone and locked eyes with the portrait on the wall once more. Yakov Peters had been Dzerzhinsky’s number two in Leningrad during the revolution, just as idealistic, and just as ruthless. Lenin had sent him to Tashkent in 1921 to solidify the Bolsheviks’ control of Central Asia, and he had done so, from this very office.

If Peters had been alive today, Muratov thought, he too would have found himself a big fish in a suddenly shrunken pond. And an even less friendly one than Muratov’s own. Peters had been a Lett, and from all the reports it seemed as if the KGB in Latvia had actually been dissolved and had not simply acquired a new mask, as was the case in Uzbekistan.

Muratov opened one of the drawers of his desk and reached in for the bottle of canyak brandy which he kept for such moments. After pouring a generous portion into the glass and taking his first medicinal gulp the NSS chief gave some serious thought to the hijack message for the first time. If it was genuine – and for some reason he felt that it was – then it also represented a new phenomenon – hijackers who didn’t want publicity. Their name obviously suggested some strain of Islamic fundamentalism, but could just as easily be a cover for men who wanted money and lots of it. Which it was would no doubt become clear when the demands arrived on the following morning.

Muratov walked across to the open window, glass in hand. The dim yellow lights on the unnamed street below were hardly cheerful.

The telephone rang, and he took three quick strides to pick it up. ‘Hamza?’ he asked. The two men had known each other a long time. Four years earlier they had been indicted together on corruption charges for their part in the Great Cotton Production Scam, which had seen Moscow paying Uzbekistan for a lot of non-existent cotton. The break-up of the Soviet Union had almost made them Uzbek national heroes.

‘Yes, Bakhtar, what can I do for you?’

The Samarkand man sounded in a good mood, Muratov thought. Not to mention sleepy. He had probably gone home for an afternoon tumble with his new wife, whom rumour claimed was half her husband’s age and gorgeous to boot.

‘I’ve just had a call,’ Muratov told him, and recited the alleged hijackers’ message word for word.

‘You want me to check it out?’

‘Immediately.’

‘Of course. Will you be in your office?’

‘Either here or at the apartment.’ He gave Zhakidov the latter’s number. ‘And make sure whoever you assign can keep their mouth shut. If this is genuine we don’t want any news getting out, at least not until we know who we’re dealing with and why.’

Nurhan Ismatulayeva studied herself in the mirror. She had tried her hair in three different ways now, but all of them seemed wrong in one way or another. She let the luxuriant black mane simply drop around her face, and stared at herself in exasperation.

The red dress seemed wrong too, now that she thought about it. It was short by Uzbek standards, far too short. If she had been going out with an Uzbek this would have been fine – he would have seen it as the statement of independence from male Islamic culture which it was intended to be. But she was going out with a Russian, and he was likely to see the dress as nothing more than a come-on. His fingers would be slithering up her thigh before the first course arrived.

She buried her nose in her hands, and stared into her own dark eyes. Why was she even going out with the creep? Because, she answered herself, she scared Islamic men to death. And since the pool of available Russians was shrinking with the exodus from Central Asia her choice was growing more and more limited.

There was always the vibrator her friend Tursanay had brought home from France.

She stared sternly at herself. Was that what her grandmother had fought for in the 1920s? Was that why she’d pursued the career she had?

She was getting things out of proportion, she told herself. This was a dinner date, not a life crisis. If he didn’t like her hair down, tough luck. If he put his hand up her dress, then she’d break a bottle over his head. Always assuming she wasn’t too drunk to care.

That decided, she picked up her bag and decided to ring for a taxi – most men seemed to find her official car intimidating.

The phone rang before she could reach it.

‘Nurhan?’ the familiar voice asked.

‘Yes, comrade,’ she said instinctively, and heard the suppressed amusement in his voice as he told her to report in at once. ‘Hell,’ she said after hanging up, but without much conviction. She hadn’t really wanted to go out with the creep anyway, and after-hours summonses from Zhakidov weren’t exactly commonplace.

She called her prospective date at his home, but the line was engaged. Too bad, she thought, and walked out to the balcony and down to the street. Her car was parked in the alley beside the house, and seemed to be covered in children. As she approached they leapt off and scurried into the darkness with melodramatic shrieks of alarm. Nurhan smiled and climbed into the driver’s seat. Of the two Samarkands which sat side by side – the labyrinthine old Uzbek city and the neat colonial-style Russian one – she had always loved the former and loathed the latter. One was alive, the other dead. And the fact that she had more in common with the people who lived in the Russian city couldn’t change that basic truth.

As she started up the car she suddenly realized that her dress was hardly the appropriate uniform for an NSS major in command of an Anti-Terrorist Unit. What the hell – Zhakidov had said ‘now’. She pressed a black-stockinged leg down on the accelerator.

It took no more than ten minutes to reach the old KGB building in Uzbekistan Street. There was a light burning in Zhakidov’s second-floor office, but the rest of the building seemed to be in darkness.

She parked outside the front door and climbed out of the car. As she crossed the pavement a taxi pulled up and disgorged Major Marat Rashidov, commander of the largely theoretical Foreign Business and Tourist Protection Unit. Rashidov had been a friend of Zhakidov’s for a long time, and those in the know said he had been given this unit for old times’ sake. The bottle was supposed to be his real vocation.

‘My God, is it an office party?’ he asked, looking at her dress.

She smiled. ‘Not unless it’s a surprise.’ There was something about Marat she had always liked, though she was damned if she knew what it was. At least he was sober. In fact, his brown eyes seemed remarkably alert.

Maybe he had moved on to drugs, she thought sourly. There were enough around these days, now that the roads to Afghanistan and Pakistan were relatively open.

The two of them walked up to Hamza Zhakidov’s office, and found the bureau chief sitting, feet on desk, blowing smoke rings at the ceiling, his bald head shining like a billiard-ball under the overhead light. He too gave Nurhan’s dress a second glance, but restricted any comment to a momentary lifting of his bushy eyebrows.

‘We may have a hijack on our hands,’ he said without preamble. ‘Someone phoned the office in Tashkent claiming that a party of tourists has been abducted here in Samarkand…’

‘Have they?’ Marat asked.

‘That’s what you’re going to find out. It’s supposedly the “Blue Domes” tour…’

‘Central Asian Tours – it’s an English firm,’ Marat interrupted, glad he had thought to do some homework on his way over in the taxi. ‘They do a ten-day tour taking in Tashkent, Bukhara and Khiva as well as here. They use the Hotel Samarkand.’

Zhakidov looked suitably impressed.

‘Has the hotel been contacted?’ Nurhan asked.

‘No. Tashkent’s orders are for maximum discretion. The hijackers…well, you might as well read it for yourselves.’ He passed over the transcription he had taken from Muratov over the phone.

Nurhan and Marat bent over it together, she momentarily distracted by the minty smell on his breath, he by the perfume she was wearing.

‘Publicity-shy terrorists,’ she muttered. ‘That’s unusual.’

‘The tourists are probably all sitting in the Samarkand’s candlelit bar, wondering when the electricity will come back on,’ Zhakidov said. ‘But just go over there and check it out.’

‘And if by some remote chance they really are missing?’ Marat asked, getting to his feet.

‘Then we start looking for them,’ Nurhan told him.

Zhakidov listened to their feet disappearing down the stairs and lit another cigarette. He supposed it was rather unkind of him, but he couldn’t help thinking a hijacked busload of tourists would make everyone’s life a bit more interesting.

Her Majesty’s Ambassador in Uzbekistan lay in the bath, his heels perched either side of the taps, a three-day-old copy of the Independent held just above the lukewarm water, an iced G&T within reach of his left hand. Reaching it without dipping a corner of the newspaper into the water was a knack gathered over the last few weeks, as the early-evening bath had gradually acquired the status of a ritual. The long days spent baking in the oven which served as his temporary office had required nothing less.

The British Embassy to Uzbekistan had only opened early the preceding year, and James Pearson-Jones had been given the ambassadorial appointment at the young age of thirty-two. His initial enthusiasm had not waned in the succeeding eighteen months, for post-Soviet Uzbekistan was such a Pandora’s Box that it could hardly fail to be continually fascinating. It was ‘the mullahs versus MTV’ as an Italian colleague had put it at one of their unofficial EU lunches, adding that he wouldn’t like to bet on the outcome.

‘God save us from both,’ had been a French diplomat’s comment.

Pearson-Jones smiled at the memory. His money was on the West and MTV – from what he could see the average Uzbek was much more interested in money than God. And the trade and aid deals to be signed over the coming weekend would put more money within their reach.

His thoughts turned to the arrangements for putting up the junior minister and various business VIPs. He had been tempted to place them all in the Hotel Uzbekistan, where his own office was, just to give the minister an insight into what life was like in Central Asian temperatures while a hotel’s air-conditioning was – allegedly, at least – in the process of being overhauled. But he had relented, and booked everyone into the Tashkent, which had the added advantage of being cheaper. After all, no one had said anything about increasing his budget to cover the upcoming binge.

There was a knock on the outside door.

He ignored it, and started rereading the cricket page. Cricket, he had to admit, was one very good reason for being in England during the summer. That and…

The knocker knocked again.

‘Coming,’ he shouted wearily. He climbed out of the bath, reached for his dressing-gown and downed the last of the G&T, then walked through to the main room of the suite and opened the door. It was his red-headed secretary, the delicious but apparently unavailable Janice. He had tried, but these days a man couldn’t try too hard or someone would start yelling sexual harassment.

She wasn’t here for his body this time either.

‘There’s been no call from Samarkand,’ she said. ‘I thought you ought to know.’

He looked at his watch, and found only an empty wrist. ‘What time is it?’

‘Eight-thirty. She should have called in at seven.’

‘What were they doing today?’

‘The Shah-i-Zinda this morning, and Shakhrisabz this afternoon.’

‘That must be it then. It’s a long drive – the bus probably broke down on the way back. Or something like that.’

‘Probably. I just thought you should know.’ She started for the door.

‘Wait a minute,’ Pearson-Jones said. There might be no brownie points for being too careful, but the Foreign Office sure as hell deducted them for not being careful enough. ‘Maybe we should check it out. We have the number of the hotel?’

‘It’s in the office.’

‘Can you get it? We’ll ring from here.’

He got dressed while Janice descended a floor to the embassy office, thinking that he’d never heard her mention a boyfriend. Still, she handled the post, and for all he knew there were a dozen letters a day from England that arrived reeking of Brut.

Dressed, he poured himself another G&T, and took it out on the concrete balcony. In the forecourt below a couple of early drunks seemed to be teaching each other the tango.

Janice knocked again, and he went to let her in. ‘You do the talking,’ he said, ‘your Uzbek is better than mine.’

Nurhan Ismatulayeva and Marat Rashidov arrived at the Hotel Samarkand some five minutes after leaving the NSS building. The coffee shop in the lobby was full of local youths, all of whom looked like bad imitations of Western rock stars. The hotel restaurant was almost empty, but one long table had been set and not used, presumably for a tour party.

Nurhan showed the receptionist her credentials, and got a scowl in return. One of these days, she thought, it would be nice to have a job which encouraged people to smile at her. Maybe she could join the state circus as a clown.

‘The Central Asian Tours group,’ she said. ‘Are they in the hotel?’

The receptionist shook his head, his eyes apparently fixed on her black-clad lower thighs.

‘Do you know where they are?’

He shook his head again.

‘Look, friend,’ Marat said cheerfully, ‘let’s have a little co-operation here.’

Reluctantly turning his attention to the male member of the duo, the receptionist gave him a pitying look. ‘They’re not back yet – that’s all I know.’

‘From where?’ Nurhan asked patiently.

‘I don’t know. This is a hotel, not a travel agency.’ Seeing the look on Marat’s face, he added: ‘You could try the notice-board in the lounge – they sometimes put the itineraries up there.’

Marat went to look.

‘Which rooms are they in?’ Nurhan asked.

He sighed and opened the register book. ‘Three-o-four to 310.’

‘Keys,’ she said, holding out her hand.

‘All of them?’

‘All of them.’

He passed them over, just as Marat returned. ‘Nothing,’ the NSS man said.

They walked up the four flights of stairs to the third floor, and let themselves into the first room. Two open suitcases half-full of neatly folded clothes lay up against a wall. If the group had been hijacked it was without a change of underwear. A novel – A Suitable Boy – lay on the bedside table. Inside the front cover ‘Elizabeth Ogley, May 1994’ had been inscribed.

They had been through three of the seven rooms before Marat found what they were looking for. Inside another paperback – Eastern Approaches by Fitzroy Maclean – the folded piece of paper used as a bookmark yielded a handwritten copy of the tour itinerary. A trip to Shakhrisabz had been scheduled for that afternoon.

‘That’s it then,’ Marat said. ‘That road across the mountains is terrible. They’ve had a puncture, or driven into a ravine or something.’

Nurhan looked at the itinerary. ‘Bit of a coincidence,’ she said, ‘that the only time they go off on a jaunt into the countryside we get a call to say they’ve been hijacked.’

‘For someone in the know that would be the best time for a hoax,’ he suggested, but with rather less confidence.

‘I think it’s for real,’ she said, walking across to the window. A car was drawing up down below, not a tour bus. This would be her first real chance to prove herself, she thought.

‘We’d better call Zhakidov,’ Marat said.

They went back downstairs to the desk, and found the receptionist had disappeared. Nurhan used his phone to call in.

‘You’d better drive over to Shakhrisabz,’ Zhakidov said. ‘If you meet them on the way, fine. If you don’t, then find out if they ever got there.’

Nurhan was not pleased. ‘Why can’t we just phone our office there?’ she wanted to know.

‘Discretion, remember?

‘It’s a nice ride,’ Marat added for good measure. And besides, he thought, it would remove him from temptation for a few hours.

Another phone suddenly started ringing in the office behind the counter.

‘Maybe it’s them,’ Marat suggested. ‘Maybe someone got taken ill and they had to find a doctor in Shakhrisabz.’

‘Maybe,’ Nurhan agreed. She moved towards the office’s open door just as the receptionist re-emerged from wherever it was that he had been skulking.

‘I’ll answer that,’ he said indignantly.

‘If it’s anything to do with the Central Asian Tours party I want to speak to them,’ Nurhan said.

‘OK, OK,’ the receptionist said, picking up the receiver. ‘Yes,’ he said, in answer to some question, glancing across at Nurhan and Marat. ‘Wait a moment,’ he told the caller, ‘the police want to speak to you.’ He held out the phone for Nurhan. ‘Who is that?’ she asked.

‘I am calling from the British Embassy in Tashkent,’ a female voice said in reasonable Uzbek. ‘I wish to talk to someone staying at the hotel. Brenda Walker.’

Nurhan cursed under her breath. ‘The group has not returned from their trip yet,’ she said.

‘Do you know why they’re late?’ the woman asked.

‘No. A problem with their bus, most likely. Do you wish to leave a message?’

‘Why are the police involved?’ the woman asked.

‘We just want to talk to the tour operators,’ Nurhan improvised. ‘Is there no message?’

‘No, I’ll try again in an hour or so.’

Nurhan put the phone down. ‘Why did you say “police”, you idiot?’ she asked the receptionist.

He shrugged. ‘You didn’t tell me not to.’

She looked at him. ‘The woman will be calling back. You will tell her the same thing I told her – that you don’t know why the tour group has not returned, but it’s probably that their bus has broken down. Is that clear?’

‘Of course.’

‘Then don’t fuck up,’ Marat warned him. ‘Or our next meeting will not be as convivial as this one has been. Now what sort of bus are they in?’

‘A small one. Green and white.’

The two NSS officers headed out through the glass doors in the direction of their car, oblivious to the disdainful finger being raised to their retreating backs.

Four hundred kilometres to the north-east Janice Wood was trying to explain the tone of the policewoman’s voice to James Pearson-Jones. ‘I’m sure she was lying, or at least not telling the whole truth. Something’s happened.’

Pearson-Jones sighed, thought for a moment, and muttered ‘shit’ with some vehemence. ‘We’d better call London,’ he said.

‘And bring Simon in?’ she asked. Simon Kennedy was ostensibly Pearson-Jones’s number two at the embassy, with a portfolio of responsibilities which included that of military attaché. He was also MI6’s representative in Central Asia.

‘Yes, bring him in,’ Pearson-Jones agreed. ‘I’ll go down to the office and make the call.’

3 (#ue4f1ade8-500e-58c3-99a8-92ddd94173e4)

In London it was nearly four in the afternoon, and the tall patrician figure of Alan Holcroft had just arrived back at the Foreign Office from the House of Commons. Prime Minister’s Question Time had been its usual farcical waste of time, and Holcroft had sat on the front bench wondering why they didn’t put a cock-fighting arena by the dispatch box, and give the two sides some real blood to cheer about. He was quite willing to agree that the occasion was a useful theoretical demonstration of democracy in action, but could see no reason why anyone with real work to do should have to sit through the damn thing twice a week.

And as Foreign Minister he had plenty of work to do. The rest of the world seemed even more of a mess than usual. The Americans had found something new to panic them – North Korea, this time – but at least for the moment they seemed to have dropped the idea of invading Haiti. Russia was still collapsing, the Brussels bureaucracy its usual irritating self, and the French as difficult as ever. Bosnia continued on its bloody way, despite losing top spot in the genocide league to Rwanda. And then there was the Middle East…If this was the New World Order, Holcroft thought, then he would hate to see chaos.

On his desk he found a memo waiting for him. The two British hostages held by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia were getting a full-page write-up in tomorrow morning’s Independent, and it was expected that the Labour MP championing their cause would be seeking a government response the following afternoon.

Holcroft sighed. What did they expect – a gunboat? That the government would send the hostage-takers to bed without any supper? The honest answer would be to say that Her Majesty’s Government had no influence whatsoever on the Khmer Rouge, and to admit in addition that it had more important things to worry about than a couple of British citizens who had been stupid enough to travel in a country that was clearly unsafe. As far as Holcroft was concerned they were like transatlantic rowers or potholers – he had no objection to them taking risks, but every objection to their using taxpayers’ time and money to pull themselves out of jams of their own making.

None of which he could say at the dispatch box. He settled down to read through the memo, confident that the author would have supplied him with either a more acceptable reason for doing nothing or a convincing explanation of how much he was already doing.

Holcroft was nearly halfway through the three-page memo when there was a sharp rap on his door. He looked at his watch – there was still at least forty minutes left of the one hour without interruption which he demanded each day. ‘Come,’ he snapped.

It was his Parliamentary Private Secretary, Michael Allsworth. ‘Sorry to interrupt you,’ the intruder said, ‘but the embassy in Tashkent has been on the line.’

Holcroft felt the familiar mixture of anger and frustration seize him by the throat. ‘What in God’s name has she done now?’ he demanded.

‘No, it’s nothing like that…it’s…well…’ Allsworth took a seat. ‘It all seems a bit iffy, Minister. The gist of it is that the tour party your daughter is with seems to have disappeared. Or at least not returned to the hotel in Samarkand when it should have. As you know, the agent assigned to your daughter is supposed to report in each day at seven local time. Today she hasn’t. But we have no actual reason to suspect foul play…’

‘No actual reason?’

‘Well, when the embassy tried to contact her at the hotel they were asked to speak to the police, which they found a bit odd.’

‘Was there no reason given for the tour party not being there?’

‘Just lateness. And that may be…’

‘What’s the time there now?’ Holcroft wanted to know.

‘About ten o’clock in Samarkand, eleven in Tashkent.’

‘And they were due back when?’

‘For dinner at eight o’clock.’

‘So it’s only two hours. That doesn’t seem much.’

‘No, it’s just…’

‘The police business. I understand.’ Holcroft considered for a moment. The familiar thought of how much easier life would be, both for him and his wife, without their youngest daughter flitted across his mind, and for once induced a slight sense of shame. Rather more to his surprise, Holcroft also felt a tinge of panic. ‘If they’re not simply late, then what are the possibilities?’ he asked Allsworth.

‘An accident of some sort, a simple hold-up, a political hijack.’

Holcroft wondered which would be worst. ‘So what do you suggest?’ he asked.

‘Get the intelligence boys working on it, just in case. After all, they’ve already got someone with the party, and MI6 have another man in Tashkent. MI5 or Special Branch can do any spadework that needs doing this end. The tour company operates out of Bradford,’ he added, in response to Holcroft’s raised eyebrow.

‘Of course.’ Sarah had told him as much when she’d announced this ridiculous jaunt. That was how he had managed to arrange the accompanying minder. ‘Right,’ he told Allsworth. ‘Do that. And call me if any news comes in. I’ll be at home.’

The secretary disappeared, leaving Holcroft with a sinking sensation in his stomach. ‘They’re just late,’ he murmured to himself, but it didn’t sound convincing. He wondered what, if anything, he was going to tell his wife Phyllis.

Marat Rashidov watched Nurhan’s thighs shift as she changed gears and had a fleeting memory of being excited by his ex-wife in similar circumstances. ‘What were you planning this evening?’ he asked.

She didn’t answer for a moment, being absorbed in circumnavigating a goat which had strayed into the middle of the road, and now seemed transfixed by the car’s headlights. ‘What did you say?’ she asked, once they were past the belligerent-looking animal.

He repeated the question.

She smiled to herself. ‘Just a dinner date,’ she said.

‘Who was the lucky man?’ he asked.

She laughed. ‘Mind your own business,’ she retorted. ‘What did you have planned?’

He grunted. ‘Nothing much.’ Another evening staring at the walls and wondering who he was staying sober for. He glanced across at Nurhan, whose black hair was now gathered at the nape of her neck and held by an elastic band she had found in one of the tourists’ rooms. Marat had known of her for a long time, occasionally run into her when their professional duties overlapped, but he had no real idea of who she was. Rumour had it that she’d screwed her way to the position she currently held, but in the predominantly male world of the Samarkand NSS such an explanation of her success was almost inevitable. Marat doubted it was true. She didn’t seem like the scheming sort. Or the sort who wanted to be beholden to anyone for anything.

‘How did you get into this work?’ he asked.

‘It’s in the family blood,’ she said. ‘My grandmother was in the Chekas during the Revolution.’

‘Tell me about her,’ Marat said.

She glanced across at him. ‘It’s ancient history,’ she said. ‘Why would you be interested?’

‘It’s going to be a long ride,’ he said. ‘Humour me.’

She shrugged. ‘She was my mother’s mother. Her name was Rahima Asankulova. She was the wife of one of the first Uzbek Bolsheviks, a very young wife. Of course he treated her like any Uzbek husband treated his wife in those days, and in 1921, when she was only about nineteen – she never knew exactly which year she was born in – she ran away to Moscow, to the headquarters of the Party women’s organization, the Zhenotdel. There was a big fuss, but six months later she came back as a Zhenotdel worker, one of the first in Central Asia. You know what they went through?’

‘I imagine they weren’t too popular.’

‘That’s an understatement if ever I heard one. They campaigned against the veil, and for an end to the selling of brides, and in favour of education for women…the usual. Some were stoned to death, some were thrown down wells, one woman was actually chopped up. All these murders were committed by fellow family members, of course.’

Glancing to his left, Marat could see her staring angrily ahead.

‘And your grandmother?’

‘She survived until the thirties, then died giving birth in one of Stalin’s prisons.’

‘To your mother?’

‘No, she was born in 1928. She worked for the Party too, though not for the KGB. She was a union representative for the Tashkent textile workers. She’s retired now, but she still lives in Tashkent…’

She broke off as two headlights appeared round a bend in the mountain road.

‘It’s a lorry,’ Marat said, rummaging in his pockets. A hand emerged holding a tube of mints. He offered her one.

She took it, wondering if she had been wrong earlier in assuming that the mint on his breath had been a cover for the smell of alcohol.

‘I’ve just given up smoking,’ he said, as if in answer to her unspoken question.

‘Good idea,’ she said.

He rearranged himself in the seat and asked her why she had joined the KGB.

She was silent for a few moments. ‘I think the main reason was that I couldn’t think of an alternative,’ she said eventually.

‘You’re joking…’

‘No. I got accepted at Moscow University, and could hardly believe my luck. I really wanted to get out of Tashkent. To get out of Central Asia, full stop.’

‘Why? You’re Uzbek…’