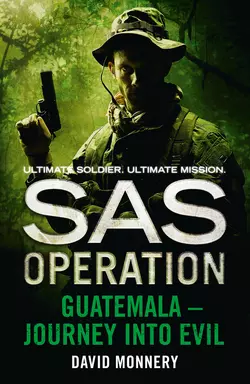

Guatemala – Journey into Evil

David Monnery

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 384.72 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But will the SAS locate their target and make it out of the jungle alive?In the Central American republic of Guatemala, government-sponsored torture and mass murder has reduced the Mayan Indian population to a despairing acquiescence. After five hundred years of struggle it seems as if the conqueror’s peace can at last be proclaimed in the capital.Then a guerrilla leader who the authorities have long believed dead springs mysteriously back to life. No loyal Guatemalan can identify him, and the government is compelled to seek help elsewhere, from one of the two SAS soldiers who helped mediate a hostage crisis with the guerrilla almost fifteen years earlier.To the government in Whitehall it appears a straightforward enough exercise, but for the soldier and his comrades the mission soon turns into a nightmare of impossible choices. The land of Guatemala, magical and cruel by turns, will prove much easier to enter than to escape…