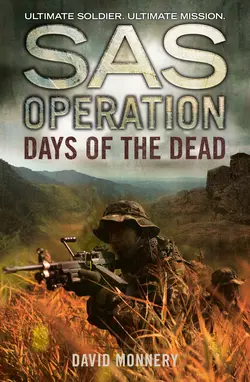

Days of the Dead

David Monnery

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 493.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But can the SAS break in to a Colombian island prison and snatch an Argentine killer?1996: a terminally ill father desperately seeks answers to what happened to his son, missing for twenty years. He has the names of two Argentine men – one in Mexico City, the other imprisoned on the Colombian island of Providencia – but no one to ask the questions.A missing girl’s family have given her up for dead when they stumble upon a Miami newspaper story mentioning two of her friends. One has just died; the other, half-deranged, tells a garbled story of sexual slavery on a Caribbean island which sounds suspiciously like Providencia.MI6 and the British government are certain that a huge drug-trafficking empire is being run from the prison, and know that some of the profits are being funnelled by its Argentine ‘guest’ into financing a mercenary invasion of the Falklands. Ignored by the Colombian authorities and mysteriously obstructed by their American allies, the British have no choice but to send in their own elite force – the SAS.