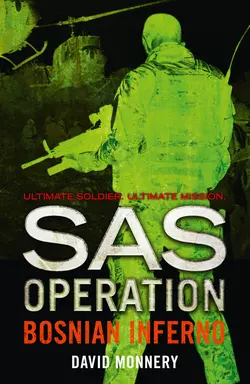

Bosnian Inferno

David Monnery

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But can the SAS lead a civilian population out of war-ravaged Bosnia to safety?Bosnia, 1993. A small army of Serbs, Muslims and Croats, formed to defend the isolated mountain town of Zavik and under the command of Reeve, a renegade Briton, has begun mounting raids further afield in search of food, fuel and medical supplies.All sides in the civil war are enraged by its exploits; even UN mediators recognize the need for its suppression. But there are only two people Reeve will listen to: his ex-wife, and an ex-comrade in the SAS. The latter is willing to lead a team into Zavik; the former has first to be found – she is either trapped in Sarajevo or imprisoned in a Serbian concentration camp.Rescuing her is only the beginning. The SAS team will then have to traverse the mountainous war zone and force their way into the besieged town. This will be difficult enough. Fighting their way out of the war-ravaged territory with a convoy of the sick, the old and the very young will be next to impossible.

Bosnian Inferno

DAVID MONNERY

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Collaboration JS / Arcangel Images (soldier); Archive Holdings Inc. / Getty Images (background)

David Monnery asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155216

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008155223

Version: 2015-11-05

Contents

Cover (#u71bd7742-ea46-588e-be02-170467d3d84d)

Title Page (#u28782ca6-9fb3-54bf-a456-8e08a145c28f)

Copyright (#ubb1e7ff5-837c-5d75-9fea-a254a1070b89)

Prelude (#u707992ea-9a9e-5dc3-9632-2c8545d38931)

Chapter 1 (#u9357a52c-382b-5d64-a67c-58099e956a36)

Chapter 2 (#u9e75bc54-95a8-5118-8191-8e088a03bdcf)

Chapter 3 (#u3c2c97d1-9620-5be4-be48-4c8d43fcd7d3)

Chapter 4 (#u760d3345-b70b-59ff-b91d-842bd4868c94)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prelude (#uc566587f-f47b-55da-a7c2-242ef5bb2108)

Zavik, 17 July 1992

The knock on the door was loud enough to wake the dead, and John Reeve had little doubt what it meant. ‘I have to go now,’ he told his son, putting the book to one side. The boy must have read the seriousness of the situation on his father’s face because he didn’t object. Reeve kissed him lightly on the forehead and hurried down the new wooden staircase he’d just finished installing in his parents-in-law’s house.

Ekrem Abdic had already opened the door to admit the others. There were four of them: Tijanic, Bobetko, Cehajic and Filipovic. One Serb, one Croat and two Muslims. Reeve knew which was which, but only because he had talked to them, visited their homes. If he had met them as strangers on the street, wearing the same jeans and T-shirts they were wearing now, he would have had no idea. The dark Tijanic looked more like a stereotypical Muslim than the blond Filipovic, whose father taught children the Koran at the town’s mosque.

‘They’re here,’ Tijanic said without preamble.

As if to verify the statement, a gunshot sounded in the distance, and then another.

‘How many of them are there?’ Reeve asked, reclaiming the Kalashnikov from where it had been hanging on the wall, out of reach of the children.

‘I counted twenty-seven, so far. One transit van and three cars, all jammed full.’

‘Let’s go,’ Reeve said. He stopped in the doorway. ‘No partisan heroics,’ he told his seventy-year-old father-in-law. ‘If it looks like we’ve failed, just take the kids and head for Zilovice.’

The old man nodded. ‘Good luck,’ he said.

The four men emerged into the early dusk, the town of Zavik spread beneath them. The sun had fallen behind the far wall of the valley, but the light it had left behind cast a meagre glow across the steep, terracotta-tiled roofs. The thought of the kids and their grandparents struggling up the mountain behind the town produced a sinking feeling in Reeve’s stomach.

At least it was summer. A light breeze was blowing down the valley but the day’s heat still clung to the narrow streets. In the distance they could hear a man shouting through a megaphone.

‘They are all in the town square,’ Cehajic told Reeve.

‘How many townspeople have gone over to them?’

‘The five who disappeared this morning, but no more that we know of.’

They were only about a hundred yards from the square now, and Reeve led them down the darker side of the street in single file. The voice grew louder, more hectoring. The leader of the intruders was demanding that all weapons and cars be brought to the square immediately, and that anyone found defying this order would have their house burnt to the ground.

Reeve smiled grimly at the reference to weapons. As far as he knew there had been only about seven working guns in the town before the Serbs arrived, and his group was carrying five of them. Two others were in the hands of Muslim ex-partisans like his father-in-law, and they intended defending their own homes and families to the death.

The five men reached the rear of the building earmarked for their observation post, and filed in across the yard and up the rickety steps at the back. The old couple who lived there waved them through to the front room, where latticed windows overlooked the town square. Once this room would have housed a harem, and its windows had been designed so that the women could look out without being seen. As such, they served Reeve’s current purpose admirably.

Several hundred people were gathered in the square, most of them looking up at the man with the megaphone, who was standing on the roof of the transit van. He wore a broad-brimmed hat, sunglasses and camouflage fatigues. A long, straggly beard hung down his chest.

On the ground in front of him two bodies lay side by side. Reeve recognized one as the town’s mayor, a Muslim named Sulejman. The other looked like his brother.

Across to one side of the square, in front of the Catholic church, the irregulars’ cars were parked in a line. All were Lada Nivas, and one had the word ‘massacre’ spray-painted along its side. Some of the invaders were leaning up against these cars, while others stood between them and the transit van, staring contemptuously at the crowd. Most were dressed like their apparent leader, though a couple had nylon stockings pulled bank-robber-style across their heads, and several were sporting Chetnik ‘Freedom or Death’ T-shirts, the words interwoven through skull and cross-bones.

Their leader had finished addressing the crowd, and was now talking to one of his cronies. Both men glanced across at the two corpses on the ground and then called over one of the men wearing a nylon mask. ‘It’s Cosic,’ Tijanic said, recognizing the local man by his walk.

The man listened to the irregulars’ leader and then pointed to one of the streets leading off the square.

‘He’s telling them where Sulejman lived,’ Reeve said. He turned to Filipovic. ‘You keep watch. One of us will be back as soon as we can.’

The other four hurried back through the house, down the steps and into the empty street. Sulejman’s house was halfway up the hill to the ruined castle, and they reached it in minutes.

The big house was deserted – either Sulejman had had the sense to move his family away, or they had witnessed his death in the square. Reeve and his men walked in through the unlocked front door and took up positions behind the colonnaded partition between hallway and living-room.

The Serbs arrived about five minutes later. There were three of them, and they sounded in a good mood, laughing and singing as they kicked their way in through the door. Several were now carrying open bottles, and not much caring how much they slopped on the floor.

‘I expect the women are hiding upstairs,’ one man said.

‘Come on down, darlings!’ another shouted out.

Reeve and the others stepped out together, firing the Kalashnikovs from the hip, and the three Serbs did a frantic dance of death as their bottles smashed on the wooden floor.

Tijanic walked forward and extracted the weapons from their grasp. ‘I’ll get these to Zukic and his boys,’ he said.

‘Three down,’ Reeve said. ‘Twenty-four to go.’

1 (#uc566587f-f47b-55da-a7c2-242ef5bb2108)

‘Daddy, help me!’ Marie insisted.

Her plea brought Jamie Docherty’s attention back to the matter in hand. His six-year-old daughter was busy trying to wrap up the present she had chosen for her younger brother, and in danger of completely immobilizing herself in holly-patterned sticky tape.

‘OK,’ he said, smiling at her and beginning the task of disentanglement. His mind had been on his wife, who at that moment was upstairs going through the same process with four-year-old Ricardo. Christmas was never a good time for Isabel, or at least not for the past eighteen years. She had spent the 1975 festive season incarcerated in the cells and torture chambers of the Naval Mechanical School outside Buenos Aires, and though the physical scars had almost faded, the mental ones still came back to haunt her.

His mind went back to their first meeting, in the hotel lobby in Rio Gallegos. It had been at the height of the Falklands War, on the evening of the day the troops went ashore at San Carlos. He had been leading an SAS intelligence-gathering patrol on Argentinian soil, and she had been a British agent, drawn to betray her country by hatred of the junta which had killed and tortured her friends, and driven her into exile. Together they had fought and driven and walked their way across the mountains to Chile.

More than ten years had passed since that day, and they had been married for almost as long. At first Docherty had thought that their mutual love had exorcized her memories, as it had exorcized his pain at the sudden loss of his first wife, but gradually it had become clear to him that, much as she loved him and the children, something inside her had been damaged beyond repair. Most of the time she could turn it off, but she would never be free of the memories, or of what she had learned of what human beings could do to one another.

Docherty had talked to his old friend Liam McCall about it; he had even, unknown to Isabel, had several conversations with the SAS’s resident counsellor. Both the retired priest and his secular colleague had told him that talking about it might help, but that he had to accept that some wounds never healed.

He had tried talking to her. After all, he had told himself, he had seen enough of death and cruelty in his army career: from Oman to Guatemala to the Falls Road. That wasn’t the same, she’d said. Nature was full of death and what looked like cruelty. What she had seen was something altogether more human – the face of evil. And he had not, and she hoped he never would.

Somehow this had created a distance between them. Not a rift – there was no conflict involved – but a distance. He felt that he had failed her in some way. That was ridiculous, and he knew it. But still he felt it.

‘Daddy!’ Marie cried out in exasperation. ‘Pay attention!’

Docherty grinned at her. ‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘I was thinking about Mummy,’ he explained.

His daughter considered this, her blue eyes looking as extraordinary as ever against the rich skin tone she’d inherited from her mother. ‘You can think about her when I’ve gone to bed,’ Marie decided.

‘Right,’ Docherty agreed, and for the next ten minutes he gave her his full attention, completing the wrapping of Ricardo’s present and conferring parental approval on Marie’s suggested alterations to his positioning of the silver balls and tinsel on the tree. And then it was bedtime, and his turn to read to Ricardo. When he had finished he stood for a moment in the doorway to Marie’s room, listening to Isabel reading, the bedside lamp making a corona around his wife’s dark head as she bent over the book.

He walked downstairs, blessing his luck for finding her. Few men, he reckoned, found one such woman in their lives, and he had found two. True, with both there had been a price. Chrissie had been killed in a road accident only months after their marriage, sending him into a downward spiral of drunkenness and self-pity which had almost cost him his career and self-respect. Like Margaret Thatcher, he had been saved by the Falklands War, and in the middle of that conflict fate had led him to Isabel, who came complete with a hurt he longed in vain to heal. But he wasn’t complaining – now, at the grand old age of forty-two, Jamie Docherty would not have swapped places with any man.

He went through to the kitchen, opened a can of beer and poured it into the half-pint mug he had liberated from an officers’ mess in Dhofar nearly twenty years before.

‘How about one for me?’ Isabel asked him from the doorway, a smile on her face.

He smiled back and reached for another can.

She sat down on the other side of the kitchen table, and they shared the silence for a few moments. Her smile had gone, he noticed.

‘What is worrying you?’ she asked suddenly.

You, he thought. ‘Nothing really,’ he said, ‘maybe the future. I’ve never been retired before. It’s a strange feeling.’ He grinned suddenly. ‘Let’s face it, we haven’t even decided which continent we’re going to live in.’

‘There’s no hurry,’ she said. ‘Let’s get Christmas out of the way first.’ She put down her half-empty glass. ‘You still want fish and chips?’ she asked.

‘Yeah, I’ll go and get them.’

‘You stay with the children. I feel like some fresh air.’

And some time on your own, Docherty thought. ‘You sure?’ he asked.

‘Sí, noes problema.’

Docherty continued sipping his beer, wondering how many other households there were in Glasgow where all four occupants often moved back and forth between English and Spanish without even noticing they had done so. He had become fluent in the latter during the half year’s compassionate leave he had spent travelling in Mexico after Chrissie’s death. Isabel had acquired her bilingual skills before meeting him, during the seven years of her enforced exile in England.

Still, their linguistic habits were hardly the strangest thing about their relationship. When they had met he had been a ten-year veteran of the SAS and she one of the few surviving members of an Argentinian urban guerrilla group. If the Sun had got hold of the story their marriage would have made the front page – something along the lines of ‘SAS Hero Weds Argie Red’.

In the public mind, and particularly on the liberal left, the Regiment was assumed to be a highly trained bunch of right-wing stormtroopers. There was some truth in this impression, particularly since the large influx during the eighties of gung-ho paras – but only some. Men like Docherty, who came from families imbued with the old labour traditions, were also well represented among the older hands, and among the new intake of younger men the SAS emphasis on intelligence and self-reliance tended to militate against the rightist bias implicit in any military organization.

On returning from the Falklands, conscious of Isabel’s opinions, Docherty had thought long and hard about whether to continue in the Army. Up to that time, he decided, none of the tasks allotted him by successive British governments had seriously troubled his conscience. When one arrived that did, then that would be the time to hand in his cards.

So, for most of the past ten years he and Isabel had lived just outside Hereford. Her cover during the mission in Argentina had been as a travel-guide writer, and a couple of enquiries were enough to confirm that the market in such books was expanding at enormous speed. She never finished the one she was supposedly researching in southern Argentina, but an offer to become one third of a team covering Chile was happily accepted, and this led to two other books on Central American countries. It meant her being away for weeks at a time, but Docherty was also often abroad for extended periods, particularly after his attachment to the SAS Training Wing. Whenever possible they joined each other, and Docherty was able to continue and deepen the love affair with Latin America which he had begun in Mexico.

Then Marie had arrived, and Ricardo two years later. Isabel had been forced to take a more editorial role, which, while more rewarding financially, often seemed considerably less fulfilling. Now with Ricardo approaching school age, and Docherty one week into retirement from the Army, they had big decisions to take. What was he going to do for a living? Did they want to live in Scotland or somewhere in Latin America? As Isabel had said, there was no urgency. She had recently inherited – somewhat to her surprise – a few thousand pounds from her mother, and the house they were now staying in had been virtually a gift from Liam McCall. The priest had inherited a cottage on Harris in the Outer Hebrides, decided to retire there, and offered the Dochertys an indefinite free loan of his Glasgow house.

No urgency, perhaps, but much as Docherty loved having more time with Isabel and the children, he wasn’t used to doing nothing. The military life was full of dead periods, but there was always the chance that the next day you would be swept across the world to face a challenge that stretched mind, body and soul to the limit. Docherty knew he had to find himself a new challenge, somehow, somewhere.

He got up to collect plates, salt, ketchup and vinegar. Just in time, for the ever-wonderful smell of fish and chips wafted in through the door ahead of his wife.

‘Cod for you, haddock for me,’ she said, placing the two bundles on the empty plates. ‘And I bought a bottle of wine,’ she added, pulling it out of the coat pocket. ‘I thought…’

The telephone started ringing in the living-room.

‘Who can that be?’ she asked, walking towards it.

Docherty had unwrapped one bundle when she returned. ‘It’s your old CO,’ she said, like any English military wife. ‘Barney Davies. And he sounds like he’s calling from a pub.’

‘Maybe they’ve realized my pension should have been twice as much,’ Docherty joked, wondering what in God’s name Davies wanted with him.

He soon found out.

‘Docherty? I’m sorry to call you at this hour, but I’d appreciate a meeting,’ Davies said.

Docherty raised his eyebrows. It did sound like a pub in the background. He tried to remember which of Hereford’s hostelries Barney Davies favoured. ‘OK. What about? Can it wait till after Christmas?’

‘Tonight would be better.’

‘Where are you?’ Docherty asked.

‘In the bar at Central Station.’

The CO was in Glasgow. Had maybe even come to Glasgow just to see him. What the fuck was this about?

‘I’m sorry about the short notice, but…’

‘No problem. In an hour, say, at nine.’

‘Wonderful. Can you suggest somewhere better than this?’

‘Aye, the Slug & Sporran in Brennan Street. It’s about a ten-minute walk, or you can take a cab…’

‘I’ll walk.’

‘OK. Just go straight down the road opposite the station entrance, then left into Sauchiehall Street and Brennan Street’s about three hundred yards down on the right. The pub’s about halfway down, opposite a pool hall.’

‘Roger.’

The phone clicked dead. Docherty stood there for a minute, a sinking heart and a rising sense of excitement competing for his soul, and then went back to his fish and chips. He removed the plate which Isabel had used to keep them warm. ‘He wants to see me,’ he said, in as offhand a voice as he could muster. ‘Tonight.’

She looked up, her eyes anxious. ‘Por qué?’ she asked.

‘He didn’t say.’

Lieutenant-Colonel Barney Davies, Commanding Officer 22 SAS Regiment, found the Slug & Sporran without much difficulty, and could immediately see why Docherty had recommended it. Unlike most British pubs it was neither a yuppified monstrosity nor a noisy pigsty. The wooden beams on the ceiling were real, and the polished wooden booths looked old enough to remember another century. There were no amusement machines in sight, no jukebox music loud enough to drown any conversation – just the more comforting sound of darts burying themselves in a dartboard. The TV set was turned off.

Davies bought himself a double malt, surveyed the available seating, and laid claim to the empty booth which seemed to offer the most privacy. At the nearest table a group of youngsters sporting punk hairstyles were arguing about someone he’d never heard of – someone called ‘Fooco’. Listening to them, Davies found it impossible to decide whether the man was a footballer, a philosopher or a film director. They looked so young, he thought.

It was ten to nine. Davies started trying to work out what he was going to say to Docherty, but soon gave up the attempt. It would be better not to sound rehearsed, to just be natural. This was not a job he wanted to offer anybody, least of all someone like Docherty, who had children to think about and a wife to leave behind.

There was no choice though. He had to ask him. Maybe Docherty would have the sense to refuse.

But he doubted it. He himself wouldn’t have had the sense, back when he still had a wife and children who lived with him.

‘Hello, boss,’ Docherty said, appearing at his shoulder and slipping back into the habit of using the usual SAS term for a superior officer. ‘Want another?’

‘No, but this is my round,’ Davies said, getting up. ‘What would you like?’

‘A pint of Guinness would probably hit the spot,’ Docherty said. He sat down and let his eyes wander round the half-empty pub, feeling more expectant than he wanted to be. Why had he suggested this pub, he asked himself. That was the TV on which he’d watched the Task Force sail out of Portsmouth Harbour. That was the bar at which he’d picked up his first tart after getting back from Mexico. The place always boded ill. The booth in the corner was where he and Liam had comprehensively drowned their sorrows the day Dalglish left for Liverpool.

Davies was returning with the black nectar. Docherty had always respected the man as a soldier and, what was rarer, felt drawn to him as a man. There was a sadness about Davies which made him appealingly human.

‘So what’s brought you all the way to Glasgow?’ Docherty asked.

Davies grimaced. ‘Duty, I’m afraid.’ He took a sip of the malt. ‘I don’t suppose there’s any point in beating about the bush. When did you last hear from John Reeve?’

‘Almost a year ago, I think. He sent us a Christmas card from Zimbabwe – that must have been about a month after he got there – and then a short letter, but nothing since. Neither of us is much good at writing letters, but usually Nena and Isabel manage to write…What’s John…’

‘You were best man at their wedding, weren’t you?’

‘And he was at mine. What’s this about?’

‘John Reeve’s not been in Zimbabwe for eight months now – he’s been in Bosnia.’

Docherty placed his pint down carefully and waited for Davies to continue.

‘This is what we think happened,’ the CO began. ‘Reeve and his wife seem to have hit a bad patch while he was working in Zimbabwe. Or maybe it was just a break-up waiting to happen,’ he added, with all the feeling of someone who had shared the experience. ‘Whatever. She left him there and headed back to where she came from, which, as you know, was Yugoslavia. How did they meet – do you know?’

‘In Germany,’ Docherty said. ‘Nena was a guest-worker in Osnabrück, where Reeve was stationed. She was working as a nurse while she trained to be a doctor.’ He could see her in his mind’s eye, a tall blonde with high Slavic cheekbones and cornflower-blue eyes. Her family was nominally Muslim, but as for many Bosnians it was more a matter of culture than religion. She had never professed any faith in Docherty’s hearing.

He felt saddened by the news that they had split up. ‘Did she take the children with her?’ he asked.

‘Yes. To the small town where she grew up. Place called Zavik. It’s up in the mountains a long way from anywhere.’

‘Her parents still lived there, last I knew.’

‘Ah. Well all this was just before the shit hit the fan in Bosnia, and you can imagine what Reeve must have thought. I don’t know what Zimbabwean TV’s like, but I imagine those pictures were pretty hard to escape last spring wherever you were in the world. Maybe not. For all we know he was already on his way. He seems to have arrived early in April, but this is where our information peters out. We think Nena Reeve used the opportunity of his visit to Zavik to make one of her own to Sarajevo, either because he could babysit the children or just as a way of avoiding him – who knows? Either way she chose the wrong time. All hell broke loose in Sarajevo and the Serbs started lobbing artillery shells at anything that moved and their snipers started picking off children playing football in the street. And she either couldn’t get out or didn’t want to…’

‘Doctors must be pretty thin on the ground in Sarajevo,’ Docherty thought out loud.

Davies grunted his agreement. ‘As far as we know, she’s still there. But Reeve – well, this is mostly guesswork. We got a letter from him early in June, explaining why he’d not returned to Zimbabwe, and that as long as he feared for the safety of his children he’d stay in Zavik…’

‘I never heard anything about it,’ Docherty said.

‘No one did,’ Davies said. ‘An SAS soldier on the active list stuck in the middle of Bosnia wasn’t something we wanted to advertise. For any number of reasons, his own safety included. Anyway, it seems that the town wasn’t as safe as Reeve’s wife had thought, and sometime in July it found itself with some unwelcome visitors – a large group of Serbian irregulars. We’ve no idea what happened, but we do know that the Serbs were sent packing…’

‘You think Reeve helped organize a defence?’

Davies shrugged. ‘It would hardly be out of character, would it? But we don’t know. All we have since then is six months of silence, followed by two months of rumours.’

‘Rumours of what?’

‘Atrocities of one kind and another.’

‘Reeve? I don’t believe it.’

‘Neither do I, but…We’re guessing that Reeve – or someone else with the same sort of skills – managed to turn Zavik into a town that was too well defended to be worth attacking. Which would work fine until the winter came, when the town would start running short of food and fuel and God knows what else, and either have to freeze and starve or take the offensive and go after what it needed. And that’s what seems to have happened. They’ve been absolutely even-handed: they’ve stolen from everyone – Muslims, Serbs and Croats. And since none of these groups, with the partial exception of the Muslims, likes admitting that somewhere there’s a town in which all three groups are fighting alongside each other against the tribal armies, you can guess who they’re all choosing to concentrate their anger against.’

‘Us?’

‘In a nutshell. According to the Serbs and the Croats there’s this renegade Englishman holed up in central Bosnia like Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now, launching raids against anyone and everyone, delighting in slaughter and madness, and probably waiting to mutter “the horror, the horror” to the man who arrives intent on terminating him with extreme prejudice.’

‘I take it our political masters are embarrassed,’ Docherty said drily.

‘Not only that – they’re angry. They like touting the Regiment as an example of British excellence, and since the cold war ended they’ve begun to home in on the idea of selling our troops as mercenaries to the UN. All for a good cause, of course, and what the hell else do we have to sell any more? The Army top brass are all for it – it’s their only real argument for keeping the sort of resource allocations they’re used to. Finding out that one of their élite soldiers is running riot in the middle of the media’s War of the Moment is not their idea of good advertising.’

Docherty smiled grimly. ‘Surprise, surprise,’ he said, and emptied his glass. He could see now where this conversation was leading. ‘Same again?’ he asked.

‘Thanks.’

Docherty gave his order to the barman and stood there thinking about John Reeve. They’d known each other almost twenty years, since they’d been thrown into the deep end together in Oman. Reeve had been pretty wild back then, and he hadn’t noticeably calmed down with age, but Docherty had thought that if anyone could turn down the fire without extinguishing it altogether then Nena was the one.

What would Isabel say about his going to Bosnia? he asked himself. She’d probably shoot him herself.

Back at the booth he asked Davies the obvious question: ‘What do you want me to do?’

‘I have no right to ask you to do anything,’ Davies answered. ‘You’re no longer a member of the Regiment, and you’ve already done more than your bit.’

‘Aye,’ Docherty agreed, ‘but what do you want me to do?’

‘Someone has to get into Zavik and talk Reeve into getting out. I don’t imagine either is going to be easy, but he’s more likely to listen to you than anyone else.’

‘Maybe.’ Reeve had never been very good at listening to anyone, at least until Nena came along. ‘How would I get to Zavik?’ he asked. ‘And where is it, come to that?’

‘About fifty miles west of Sarajevo. But we haven’t even thought about access yet. We can start thinking about the hows if and when you decide…’

‘If you should choose to accept this mission…’ Docherty quoted ironically.

‘…the tape will self-destruct in ten seconds,’ Davies completed for him. Clearly both men had wasted their youth watching crap like Mission Impossible.

‘I’ll need to talk with my wife,’ Docherty said. ‘What sort of time-frame are we talking about?’ It occurred to him, absurdly, that he was willing to go and risk his life in Bosnia, but only if he could first enjoy this Christmas with his family.

‘It’s not a day-on-day situation,’ Davies said. ‘Not as far as we know, anyway. But we want to send a team out early next week.’

‘The condemned men ate a hearty Christmas dinner,’ Docherty murmured.

‘I hope not,’ Davies said. ‘This is not a suicide mission. If it looks like you can’t get to Zavik, you can’t. I’m not sacrificing good men just to put a smile on the faces of the Army’s accountants.’

‘Who dares wins,’ Docherty said with a smile.

‘That’s probably what they told Icarus,’ Davies observed.

‘Don’t you want me to go?’ Docherty asked, only half-seriously.

‘To be completely honest,’ Davies said, ‘I don’t know. Have you been following what’s happening in Bosnia?’

‘Not as much as I should have. My wife probably knows more about it than I do.’

‘It’s a nightmare,’ Davies said, ‘and I’m not using the word loosely. All the intelligence we’re getting tells us that humans are doing things to each other in Bosnia that haven’t been seen in Europe since the religious wars of the seventeenth century, with the possible exception of the Russian Front in the last war. We’re talking about mass shootings, whole villages herded into churches and burnt alive, rape on a scale so widespread that it must be a coordinated policy, torture and mutilation for no other reason than pleasure, war without any moral or human restraint…’

‘A heart of darkness,’ Docherty murmured, and felt a shiver run down his spine, sitting there in his favourite pub, in the city of his birth.

After giving Davies a lift to his hotel Docherty drove slowly home, thinking about what the CO had told him. Part of him wanted to go, part of him wasn’t so sure. Did he feel the tug of loyalty, or was his brain just using that as a cover for the tug of adventure? And in any case, didn’t his wife and children have first claim on his loyalty now? He wasn’t even in the Army any more.

She was watching Newsnight on TV, already in her dressing-gown, a glass of wine in her hand. The anxiety seemed to have left her eyes, but there was a hint of coldness there instead, as if she was already protecting herself against his desertion.

Ironically, the item she was watching concerned the war in Bosnia, and the refugee problem which had developed as a result. An immaculately groomed Conservative minister was explaining how, alas, Britain had no more room for these tragic victims. After all, the UK had already taken more than Liechtenstein. Docherty wished he could use the Enterprise’s transporter system to beam the bastard into the middle of Tuzla, or Srebenica, or wherever it was this week that he had the best chance of being shredded by reality.

He poured himself what remained of the wine, and found Isabel’s dark eyes boring into him. ‘Well?’ she asked. ‘What did he want?’

‘He wants me to go and collect John Reeve from there,’ he said, gesturing at the screen.

‘But they’re in Zimbabwe…’

‘Not any more.’ He told her the story that Davies had told him.

When he was finished she examined the bottom of her glass for a few seconds, then lifted her eyes to his. ‘They just want you to go and talk to him?’

‘They want to know what’s really happening.’

‘What do they expect you to say to him?’

‘They don’t know. That will depend on whatever it is he’s doing out there.’

She thought about that for a moment. ‘But he’s your friend,’ she said, ‘your comrade. Don’t you trust him? Don’t you believe that, whatever he’s doing, he has a good reason for doing it.’

It was Docherty’s turn to consider. ‘No,’ he said eventually. ‘I didn’t become his friend because I thought he had flawless judgement. If I agree with whatever it is he’s doing, I shall say so. To him and Barney Davies. And if I don’t, the same applies.’

‘Are they sending you in alone?’

‘I don’t know. And that’s if I agree to go.’

‘You mean, once I give you my blessing.’

‘No, no, I don’t. That’s not what I mean at all. I’m out of the Army, out of the Regiment. I can choose.’

There was both amusement and sadness in her smile. ‘They’ve still got you for this one,’ she said. ‘Duty and loyalty to a friend would have been enough in any case, but they’ve even given you a mystery to solve.’

He smiled ruefully back at her.

She got up and came to sit beside him on the sofa. He put an arm round her shoulder and pulled her in. ‘If it wasn’t for the niños I’d come with you,’ she said. ‘You’ll probably need someone good to watch your back.’

‘I’ll find someone,’ he said, kissing her on the forehead. For a minute or more they sat there in silence.

‘How dangerous will it be?’ she asked at last.

He shrugged. ‘I’m not sure there’s any way of knowing before we get there. There are UN troops there now, but I don’t know where in relation to where Reeve is. The fact that it’s winter will help – there won’t be as many amateur psychopaths running around if the snow’s six feet deep. But a war zone is a war zone. It won’t be a picnic.’

‘Who dares had better damn well come home,’ she said.

‘I will,’ he said softly.

2 (#uc566587f-f47b-55da-a7c2-242ef5bb2108)

Nena Reeve pressed the spoon down on the tea-bag, trying to drain from it what little strength remained without bursting it. She wondered what they were drinking in Zavik. Probably melted snow.

Her holdall was packed and ready to go, sitting on the narrow bed. The room, one of many which had been abandoned in the old nurses’ dormitory, was about six feet by eight, with one small window. It was hardly a generous space for living, but since Nena usually arrived back from the hospital with nothing more than sleep in mind, this didn’t greatly concern her.

Through the window she had a view across the roofs below and the slopes rising up on the other side of the Miljacka valley. In the square to the right there had once been a mosque surrounded by acacias, its slim minaret reaching hopefully towards heaven, but citizens hungry for fuel had taken the trees and a Serbian shell had cut the graceful tower in half.

There was a rap on the door, and Nena walked across to let in her friend Hajrija Mejra.

‘Ready?’ Hajrija asked, flopping down on the bed. She was wearing a thick, somewhat worn coat over camouflage fatigue trousers, army boots and a green woollen scarf. Her long, black hair was bundled up beneath a black woolly cap, but strands were escaping on all sides. Hajrija’s face, which Nena had always thought so beautiful, looked as gaunt as her own these days: the dark eyes were sunken, the high cheekbones sharp enough to cast deep shadows.

Well, Hajrija was still in her twenties. There was nothing wrong with either of them that less stress and more food wouldn’t put right. The miracle wasn’t how ill they looked – it was how the city’s 300,000 people were still coping at all.

She put on her own coat, hoping that two sweaters, thermal long johns and jeans would be warm enough, and picked up the bag. ‘I’m ready,’ she said reluctantly.

Hajrija pulled herself upright, took a deep breath and stood up. ‘I don’t suppose there’s any point in trying to persuade you not to go?’

‘None,’ Nena said, holding the door open for her friend.

‘Tell me again what this Englishman said to you,’ Hajrija said as they descended the first flight of stairs. The lift had been out of operation for months. ‘He came to the hospital, right?’

‘Yes. He didn’t say much…’

‘Did he tell you his name?’

‘Yes. Thornton, I think. He said he came from the British Consulate…’

‘I didn’t know there was a British Consulate.’

‘There isn’t – I checked.’

‘So where did he come from?’

‘Who knows? He didn’t tell me anything, he just asked questions about John and what I knew about what was happening in Zavik. I said, “Nothing. What is happening in Zavik?” He said that’s what he wanted to know. It was like a conversation in one of those Hungarian movies. You know, two peasants swapping cryptic comments in the middle of an endless cornfield…’

‘Only you weren’t in a cornfield.’

‘No, I was trying to deal with about a dozen bullet and shrapnel wounds.’

They reached the bottom of the stairs and cautiously approached the doors. It had only been light for about half an hour, and the Serb snipers in the high-rise buildings across the river were probably deep in drunken sleep, but there was no point in taking chances. The fifty yards of open ground between the dormitory doors and the shelter of the old medieval walls was the most dangerous stretch of their journey. Over the last six months more than a dozen people had been shot attempting it, three fatally.

‘Ready?’ Hajrija asked.

‘I guess.’

The two women flung themselves through the door and ran as fast as they could, zigzagging across the open space. Burdened down by the holdall, Nena was soon behind, and she could feel her stomach clenching with the tension, her body braced for the bullet. Thirty metres more, twenty metres, ten…

She sank into the old Ottoman stone, gasping for breath.

‘You’re out of shape,’ Hajrija said, only half-joking.

‘Whole bloody world’s out of shape,’ Nena said. ‘Let’s get going.’

They walked along the narrow street, confident that they were hidden from snipers’ eyes. There was no one about, and the silence seemed eerily complete. Usually by this time the first shells of the daily bombardment had landed.

It was amazing how they had all got used to the bombardment, Nena thought. Was it a tribute to human resilience, or just a stubborn refusal to face up to reality? Probably a bit of both. She remembered the queue in front of the Orthodox Cathedral when the first food supplies had come in by air. A sniper had cut down one of the people in the line, but only a few people had run for cover. There were probably a thousand people in the queue, and like participants in a dangerous sport each was prepared to accept the odds against being the next victim. Such a deadening of the nerve-ends brought a chill to her spine, but she understood it well enough. How many times had she made that sprint from the dormitory doors? A hundred? Two hundred?

‘Even if you’re right,’ Hajrija said, ‘even if Reeve has got himself involved somehow, I don’t see how you can help by rushing out there. You do know how unsafe it is, don’t you? There’s no guarantee you’ll even get there…’

Nena stopped in mid-stride. ‘Please, Rija,’ she said, ‘don’t make it any more difficult. I’m already scared enough, not to mention full of guilt for leaving the hospital in the lurch. But if Reeve is playing the local warlord while he’s supposed to be looking after the children, then…’ She shook her head violently. ‘I have to find out.’

‘Then let me come with you. At least you’ll have some protection.’

‘No, your place is here.’

‘But…’

‘No argument.’

Sometimes Nena still found it hard to believe that her friend, who six months before had been a journalism student paying her way through college as a part-time nurse, was now a valued member of an élite anti-sniper unit. Someone who had killed several men, and yet still seemed the same person she had always been. Sometimes Nena worried that there was no way Hajrija had not been changed by the experiences, and that it would be healthier if these changes showed on the surface, but at others she simply put it down to the madness that was all around them both. Maybe the fact that they were all going through this utter craziness would be their salvation.

Maybe they had all gone to hell, but no one had bothered to make it official.

‘I’ll be all right,’ she said.

Hajrija looked at her with exasperated eyes.

‘Well, if I’m not, I certainly don’t want to know I’ve dragged you down with me.’

‘I know.’

They continued on down the Marsala Tita, sprinting across two dangerously open intersections. There were more people on the street now, all of them keeping as close to the buildings as possible, all with skin stretched tight across the bones of their scarf-enfolded faces.

It was almost eight when they reached the Holiday Inn, wending their way swiftly through the Muslim gun emplacements in and around the old forecourt. The hotel itself looked like Beirut on a bad day, its walls pock-marked with bullet holes and cratered by mortar shells. Most of its windows had long since been broken, but it was still accommodating guests, albeit a restricted clientele of foreign journalists and ominous-looking ‘military delegations’.

‘He’s not here yet,’ Hajrija said, looking round the lobby.

Nena followed her friend’s gaze, and noticed an AK47 resting symbolically on the receptionist’s desk.

‘Here he is,’ Hajrija said, and Nena turned to see a handsome young American walking towards them. Dwight Bailey was a journalist, and several weeks earlier he had followed the well-beaten path to Hajrija’s unit in search of a story. She was not the only woman involved in such activities, but she was probably, Nena guessed, one of the more photogenic. Bailey had not been the first to request follow-up interviews in a more intimate atmosphere. Like his bed at the Holiday Inn, for example. So far, or at least as far as Nena knew, Hajrija had resisted any temptation.

Bailey offered the two women a boyish smile full of perfect American teeth, and asked Hajrija about the other members of her unit. He seemed genuinely interested in how they were, Nena thought. If age made all journalists cynical, he was still young.

And somewhat hyperactive. ‘Dmitri’s late,’ he announced, hopping from one foot to the other. ‘He and Viktor are our bodyguards,’ he told Nena. ‘Russian journalists. Good guys. The Serbs don’t mess with the Russians if they can help it,’ he explained. ‘The Russians are about the only friends they have left.’

He said this with absolute seriousness, as if he could hardly believe it.

‘Hey, here they are,’ he called out as the two Russians came into view on the stairs. Both men had classically flat Russian faces beneath the fur hats; both were either bear-shaped or wearing enough undergarments to survive a cold day in Siberia. In fact the only obvious way of distinguishing one from the other was by their eyebrows: Viktor’s were fair and almost invisible, Dmitri’s bushy and black enough for him to enter a Brezhnev-lookalike contest. Both seemed highly affable, as if they’d drunk half a pint of vodka for breakfast.

The two women embraced each other. ‘Be careful,’ Hajrija insisted. ‘And don’t take any risks. And come back as soon as you can.’ She turned to the American. ‘And you take care of my friend,’ she ordered him.

He tipped his head and bowed.

The four travellers threaded their way out through the hotel’s kitchens to where a black Toyota was parked out of sight of snipers. The two Russians climbed into the front, and Nena and Bailey into the back.

Two distant explosions, one following closely on the other, signalled the beginning of the daily bombardment. The shells had fallen at least two kilometres away, Nena judged, but that didn’t mean the next ones wouldn’t fall on the Toyota’s roof.

Viktor started up the car and pulled it out of the car park, accelerating all the while. The most dangerous stretch of road ran between the Holiday Inn and the airport, and they were doing more than sixty miles per hour by the time the car hit open ground. Viktor had obviously passed this way more than once, for as he zigzagged wildly to and fro, past the burnt-out hulks of previous failed attempts, he was casually lighting up an evil-smelling cigarette from the dashboard lighter.

Nena resisted the temptation to squeeze herself down into the space behind the driver’s seat, and was rewarded with a glimpse of an old woman searching for dandelion leaves in the partially snow-covered verge, oblivious to their car as it hurtled past.

Thirty seconds later and they were through ‘Murder Mile’, and slowing for the first in a series of checkpoints. This one was manned by Bosnian police, who waved them through without even bothering to examine the three men’s journalistic accreditation. Half a mile further, they were waved down by a Serb unit on the outskirts of Ilidza, a Serb-held suburb. The men here wore uniforms identifying them as members of the Yugoslav National Army. They were courteous almost to a fault.

‘Hard to believe they come from Mordor,’ Bailey said with a grin.

It was, Nena thought. Sometimes it was just too easy to think all Serbs were monsters, to forget that there were still 80,000 of them in Sarajevo, undergoing much the same hardships and traumas as everyone else. And then it became hard to understand how the men on the hills above Sarajevo could deliberately target their big guns on the hospitals below, and how the snipers in the burnt-out tower blocks could deliberately blow away children barely old enough to start school.

They passed safely through another Serb checkpoint and, as the two Russians pumped Bailey about their chances of emigration to the USA, the road ran up out of the valley, the railway track climbing to its left, the rushing river falling back towards the city on its right. Stretches of dark conifers alternated with broad swathes of snow-blanketed moorland as they crested a pass and followed the sweeping curves of the road down into Sanjic. Here a minaret still rose above the roofs of the small town nestling in its valley, and as they drove through its streets Nena could see that the Christian churches had not paid the price for the mosque’s survival. Sanjic had somehow escaped the war, at least for the moment. She hoped Zavik had fared as well.

‘This must have been what all of Bosnia was like before the war,’ Bailey said beside her. There was a genuine sadness in his voice which made her wonder if she had underestimated him.

‘How long have you been here?’ she asked.

‘I came in early November,’ he said.

‘Who do you work for?’

‘No one specific. I’m a freelance.’

She looked out of the window. ‘If you get the chance,’ she said, ‘and if this war ever ends, you should come in the spring, when the trees are in blossom. It can look like an enchanted land at that time of year.’

‘I’d love to,’ he said. ‘I…I thought I knew quite a lot of the world before I came here,’ he said. ‘I’ve been all over Europe, all over the States of course, to Australia and Singapore…But I feel like I’ve never been anywhere like this. And I don’t mean the war,’ he said hurriedly, ‘though maybe that’s what makes everything more vivid. I don’t know…’

She smiled at him, and felt almost like patting his hand.

The road was climbing again now, a range of snow-covered mountains looming on their left. She remembered the trip across the mountains to Umtali while they were in Africa. The children had been bored in the back seat and she’d been short-tempered with them. Reeve, though, had for once been an exemplary father, painstakingly prising them out of their sulk. But he’d always been a good father, much to her surprise. She’d expected a great husband and a poor father, and ended up with the opposite.

No, that was harsh.

She wondered again what she would find in Zavik, always assuming she got there. The three journalists were only taking her as far as Bugojno, and from there she would probably still have a problem making it up into the mountains. The roads might be open, might be closed – at this time of the year the chances were about fifty-fifty.

The car began slowing down and she looked up to see a block on the road ahead. A tractor and a car had been positioned nose to nose at an angle, and beside them four men were standing waiting. Two of them were wearing broad-brimmed hats. ‘Chetniks,’ one of the Russians said, and she could see the straggling beards sported by three of the four. The other man, it soon became clear, wasn’t old enough to grow one.

From the first moment Nena had a bad feeling about the situation. The Russians’ bonhomie was ignored, their papers checked with a mixture of insolence and sarcasm by the tall Serb who seemed to be in charge. ‘Don’t you think Yeltsin is a useless wanker?’ he asked Viktor, who agreed vociferously with him, and said that in his opinion Russia could declare itself in favour of a Greater Serbia. The Chetnik just laughed at him, and moved on to Bailey. ‘You like Guns ’N’ Roses?’ he asked him in English.

‘Who?’ Bailey asked.

‘Rock ’n’ roll,’ the Chetnik said. ‘American.’

‘Sorry,’ Bailey said.

‘It’s OK,’ the Chetnik said magnanimously, and looked at Nena. His pupils seemed dilated, probably by drugs of some kind or another. ‘Leave the woman behind,’ he told the Russians in Serbo-Croat.

The Russians started arguing – not, Nena thought, with any great conviction.

‘What’s going on?’ Bailey wanted to know.

She told him.

‘But they can’t do that!’ he exclaimed, and before Nena could stop him he was opening the door and climbing out on to the road. ‘Look…’ he started to say, and the Chetnik’s machine pistol cracked. The American slid back into Nena’s view, a gaping hole where an eye had been.

The Russians in the front seat seemed suddenly frozen into statues.

‘We just want the woman,’ the Chetnik was telling them.

Viktor turned round to face her, his eyes wide with fear. ‘I think…’

She shifted across the back seat and climbed out of the same door the American had used. She started bending down to examine him, but was yanked away by one of the Chetniks. The leader grabbed the dead man by the feet and unceremoniously dragged him away through the light snow and slush to the roadside verge. There he gave the body one sharp kick. ‘Guns ’N’ Roses,’ he muttered to himself.

The Russians had turned the Toyota around as ordered, and were anxiously awaiting permission to leave. Both were making certain they avoided any eye contact with her.

‘Get the fuck out of here,’ the leader said contemptuously, and the car accelerated away, bullets flying above it from the guns of the grinning Chetniks.

She stood there, waiting for them to do whatever they were going to do.

The CO’s office looked much as Docherty remembered it: the inevitable mug of tea perched on a pile of papers, the maps and framed photographs on the wall, the glimpse through the window of bare trees lining the parade ground, and beyond them the faint silhouette of the distant Black Mountains. The only obvious change concerned the photograph on Barney Davies’s desk: his children were now a year older, and his wife was nowhere to be seen.

‘Bring in a cup of tea,’ the CO was saying into the intercom. ‘And a rock cake?’ he asked Docherty.

‘Why not,’ Docherty said. He might as well get used to living dangerously again. There were some at the SAS’s Stirling Lines barracks who claimed that the Regiment had lost more men to the Mess’s rock cakes than to international terrorism. It was a vicious lie, of course – the rock cakes were disabling rather than lethal.

‘Is there any news of Reeve?’ Docherty asked.

‘None, but his wife’s still in Sarajevo, working at the hospital as far as we know.’

‘Where’s the information coming from?’

‘MI6 has a man in the city. Don’t ask me why. The Foreign Office has got him digging around for us.’

Docherty’s tea arrived, together with an ominous-looking rock cake. ‘I’m hoping to take her with me,’ he told Davies. ‘Even if they’ve separated I still think he’s more likely to listen to her than anyone else.’

‘Well, you can ask her when you get there…’

‘Sarajevo?’ Docherty asked, his mouth half full of what tasted like an actual rock. Sweet perhaps, but hard and gritty all the same.

‘It’s not been a very good year for them,’ Davies said, observing the expression on Docherty’s face, and causing the Scot to wonder whether the CO had racks of the damn things in his cellar, each bearing their vintage.

‘Sarajevo looks like the best place to begin,’ Davies continued. ‘Nena Reeve is there, and your MI6 contact. His name’s Thornton, by the way. There must be people from Zavik who can fill you in on the town and its surroundings. Plus, there’s the UN command and a lot of journalists. You should be able to pick up a good idea of what the best access route is, and what to expect on the way. Always assuming we can get you into the damn city, of course.’

‘I thought the airport was closed.’

‘Opened again a couple of days ago for relief flights, but there’s no certainty it will still be open tomorrow. If it’s not the Serbs lobbing shells from the hilltops it’s the Muslims and Serbs exchanging fire across the damn runway, and even if they’re all on their best behaviour it’s probably only because there’s a blizzard.’

‘Lots of package tours, are there?’ Docherty asked.

‘The more I know about this war the less I’m looking forward to seeing any of my men involved in it,’ Davies said.

Docherty took a gulp of tea, which at least scoured his mouth of cake. ‘How many men am I taking in?’ he asked.

‘It’s up to you, within reason. But I’d stick with a four-man patrol…’

‘So would I. Are Razor Wilkinson and Ben Nevis available?’ Darren Wilkinson and Stewart Nevis were two of the three men who had been landed on the Argentinian mainland with him during the Falklands – the third, Nick Wacknadze, had left the SAS – and Docherty had found both to be near-perfect comrades-in-arms.

‘Nevis is in plaster, I’m afraid. He and his wife went skiing over Christmas – French Alps, I think – and he broke a leg. Sergeant Wilkinson is around, though. And I think he’ll probably jump at the chance to get away from mothering the new boys up on the Beacons.’

‘Good. I’ve missed his appalling cockney sense of humour.’

‘Any other ideas?’

Docherty thought for a moment. ‘I’m out of touch, boss…’

‘Do you remember the Colombian business?’ Davies asked.

‘Who could forget it?’

Back in 1989 an SAS instructor on loan to the Colombian Army Anti-Narcotics Unit had been kidnapped, along with a prominent local politician, by one of the cocaine cartels. A four-man team had been inserted under cover to provide reconnaissance, and then an entire squadron parachuted in to assist with the rescue. One of the helicopters sent in to extract everyone was destroyed by sabotage and the original four-man patrol, plus the instructor, had been forced to flee Colombia on foot. In the process two of them had been killed, but the patrol’s crossing of a 10,000-foot mountain range, pursued all the way by agents of the cartel, had acquired almost legendary status in Special Forces circles.

‘Wynwood’s in Hong Kong,’ Davies said, ‘but how about Corporals Martinson and Robson? They’ve proved they can walk across mountains, and it seems Yugoslavia – or whatever we have to call it these days – is full of them. And’ – the CO’s face suffused with sudden enthusiasm – ‘I have a feeling Martinson has another useful qualification.’ He reached for the intercom. ‘Get me Corporal Martinson’s service record,’ he told the orderly.

Docherty sipped his tea, allowing Davies his moment of drama.

The file arrived, Davies skimmed through it, and stabbed a finger at the last page. ‘Serbo-Croat,’ he said triumphantly.

‘What?’ Docherty exclaimed. He could hardly believe there was a Serbo-Croat speaker in the Regiment.

‘You know what it’s like,’ Davies said. ‘The chances for action are few and far between these days, so the moment some part of the world looks like going bad the keen ones pick that language to learn, just in case. If nothing happens, any new language is still a plus on their record, and if by chance we get involved, they’re first in the queue.’

‘Looks like Martinson’s won the jackpot this time,’ Docherty said, reaching for the file to examine the photograph. ‘He even looks like a Slav,’ he added.

‘He’s a medic, like Wilkinson, but that might well come in useful where you’re going. And he’s a twitcher, too. A bird-watcher,’ Davies explained, seeing the expression on Docherty’s face. ‘Bosnia’s probably knee-deep in rare species.’

‘I’ll keep my eyes open,’ Docherty said drily. He had never been able to understand the fascination some people had with birds. ‘What about Robson?’

‘He’s an explosives man, and a crack shot with a sniper rifle. Which leaves you without a signals specialist, but I imagine you can fill in there yourself.’

‘Those PRC 319s work themselves,’ Docherty replied, ‘and anyway, who will we have to send signals to?’

‘Well, you might need to make contact with one of the British units who are serving with the UN.’

‘But they wouldn’t be able to get involved with this mission?’

‘No, and in any case you won’t be in uniform. This mission is about as official as Kim Philby’s.’

‘So when it comes down to it we’re just a bunch of Brits dropping in to help out a mate.’

Davies opened his mouth to object, and closed it again. ‘I suppose you are,’ he agreed.

A little more than twenty miles to the south, Chris Martinson was moving stealthily, trying not to step on any of the twigs spread across the forest floor. He halted for a moment, ears straining, and right on cue heard the ‘yah-yah-yah’ laughing sound. It was nearer now, but he still couldn’t see the bird. And then, suddenly, it seemed to be flying straight towards him down an avenue between the bare trees, its red crown, black face and green-gold back looking almost tropical in the winter forest. It seemed to see him at the last moment, and veered away to the left, into a stand of conifers.

The green woodpecker wasn’t a rare bird, but it was one of Martinson’s favourites, and, since a day trip from Hereford to the Forest of Dean never seemed quite complete if he didn’t see one, there was a smile on his face as he continued his walk.

Another quarter of a mile brought him to the crown of a small hill giving a view out across the top of the trees towards the Severn Estuary. Some kind soul had arranged for a wrought-iron seat to be placed there, and Chris gratefully sat himself down, putting his binoculars to one side and unwrapping the packed lunch he had brought with him. As he bit into the first tuna roll a flock of white-faced geese flew overhead towards the estuary.

It had been a good idea to come out for the day, Chris decided. The older he got the more claustrophobic the barracks seemed to get. He supposed it was time he got a place of his own, but somehow he had always resisted the idea. Flats were hard to find and you had all the hassle of dealing with a landlord, and as for buying somewhere…well, it would only be a millstone round his neck when he eventually left the Regiment and did some serious travelling.

He had turned thirty that year, and the time for decision couldn’t be that far off. And, he had to admit, he was getting bored with the same old routines – routines that only seemed to be interrupted these days by a few hairy weeks in sun-soaked Armagh or exotic Crossmaglen. Even the birds in Northern Ireland seemed depressed by the weather.

He ran a hand through his spiky hair. His life was in a rut, he thought. Not an unpleasant one – in fact quite a comfortable one – but a rut nevertheless. He hadn’t really made any close friends in the Regiment since Eddie Wilshaw, and the man from Hackney had died in Colombia three years before. And he hadn’t had anything approaching a relationship with a woman for almost as long. The last one he’d gone out with had told him he seemed to be living on a separate planet from the rest of humanity.

He smiled good-naturedly at the memory. She was probably right, and it was no doubt time he started reaching out to people a bit more, but…

A robin landed in a tree across the clearing and began making its ‘tick’ calling sound. Chris sat there watching it, feeling full of nature’s wonder, thinking that life on your own planet had its compensations.

3 (#uc566587f-f47b-55da-a7c2-242ef5bb2108)

Docherty could hear the familiar London accent before he was halfway down the corridor.

‘…and in hot climates there’s one last resort when it comes to infected wounds. Any ideas?’

‘A day on the beach, boss?’ a northern voice asked.

‘Several rum and cokes?’

‘I can see you’ve all read the book. The answer is maggots. Since they only eat dead tissue they act as cleaning agents in any open wound…’

‘But boss, if I’ve just been cut open by some guerrilla psycho with a machete I’m probably going to be a long way from the local fishing tackle shop…’

‘No problem, Ripley. Once the wound gets infected you can just sit yourself down somewhere and ooze pus. The maggots will come to you. Especially you. Right. Yesterday you were all given five minutes to write down the basic rules of dealing with dog bites, snake bites and bee stings. Most of you managed to survive all three. Trooper Dawson, however,’ – a collective groan was audible through the room’s open skylight – ‘used the opportunity to attempt suicide. He didn’t report the dog bite, so he may have rabies by now. It’s true that in this country he’d need to be very unlucky, but the Regiment does occasionally venture abroad. And it doesn’t really matter in any case because the snake got him. He not only wasted time trying to suck out the venom, but managed to lose an arm or a leg by applying a tourniquet instead of a simple bandage. Of course he probably didn’t notice the limb dropping off because of the pain from the bee sting, which he’d made worse by squeezing the poison sac.’

In his mind’s eye Docherty could see the expression on Razor’s face.

‘Well done, Dawson,’ Razor concluded. ‘Your only worry now is whether your mates will bother to bury you. Any questions from those of you still in the land of the almost-living?’

‘What do you do about a lovebite from a beautiful enemy agent?’ a Welsh voice asked.

‘In your case, Edwards, dream of getting one. Class dismissed. And read the fucking book.’

The Continuation Training class filed out, looking as young and fit as Docherty remembered being twenty years before. When the last man had emerged he could see Darren Wilkinson bent over a ring binder of notes on the instructor’s desk. Razor looked, like Docherty himself, as wiry as ever, but there was a seriousness of expression on the face which Docherty didn’t remember seeing very often in the past. Maybe life in the Training Wing was calming him down.

Razor looked up suddenly, conscious of someone’s eyes on him, and his face slowly split open in the familiar grin. ‘Boss. What are you doing here? If you’ve not retired I want my twenty pee back.’

‘Which twenty pee might that be?’

‘The one I gave to your passing-out collection.’

Docherty sat down in the front row and eyed him tolerantly. ‘I’m recruiting,’ he said.

‘What for?’

‘A journey into hell by all accounts.’

‘Forget it. I’m not going to watch Arsenal for anybody.’

‘How about Red Star Sarajevo?’

Razor lifted himself on to the edge of the desk. ‘Tell me about it,’ he said.

‘Do you know John Reeve?’ Docherty asked.

‘To say hello to. Not well. I never did an op with him.’

‘I did,’ Docherty said. ‘Several of them. We may not have actually saved each other’s lives in Oman, but we probably saved each other from dying of boredom. We became good mates, and though we never fought together again, we stayed that way, you know the way some friends are – you only need to see them once a year, or even every five years, and it’s still always like you’ve never been apart.’

He paused, obviously remembering something. ‘Reeve was one of the people who helped me through my first wife’s death. In fact if he hadn’t persuaded me to get compassionate leave rather than simply go AWOL I’d have been out of this Regiment long ago…Anyway, I was best man at his wedding, and he was at mine. And we both married foreigners, which sort of further cemented the friendship. You know my wife – you were there when we met…’

‘Almost. I was there when you had your first argument. About which way we should be running, I think.’

‘Aye, well, we’ve had a few since, but…’ Docherty smiled inwardly. ‘Reeve married a Yugoslav, a Bosnian Muslim as it turns out, though no one seemed too bothered by such things back in 1984. He and Nena had two children, a girl first and then a boy, just like me and Isabel. Nena seemed happy enough living in England, and then about eighteen months ago Reeve got an advisory secondment to the Zimbabwean Army. I haven’t seen him since, and I hadn’t heard anything since last Christmas, which should have worried me, but, you know how it is…Then last week, two days before Christmas, the CO comes to visit me in Glasgow.’

‘Barney Davies? He just turned up?’

‘Aye, he did.’

‘With news of Reeve?’

‘Aye.’

Docherty told Razor the story as Davies had told it to him, ending with the CO’s request for him to lead in a four-man team.

‘And it looks like you said yes.’

‘Aye, eventually. Christ knows why.’

‘Have they reinstated you?’

‘Temporarily. But since the team won’t be wearing uniform, and will have no access whatsoever to any military back-up it doesn’t seem particularly relevant.’

Razor stared at him. ‘Let me get this straight,’ he said eventually. ‘They want us to fight our way across a war zone so we can have a friendly chat with your friend Reeve, either slap his wrist or not when we hear his side of the story, and then fight our way back across the same war zone. And we start off by visiting the one city in the world which no one can get into or out of.’

Docherty grinned at him. ‘You’re in, then?’

‘Of course I’m fucking in. You think I like teaching first aid to ex-paras for a living?’

‘I now pronounce you man and wife,’ the vicar said, and perhaps it was the familiarity of the words which jolted Damien Robson out of his reverie. The Dame, as he was known to all his regimental comrades, cast a guilty glance around him, but no one seemed to have noticed his mental absence from the proceedings.

‘You may kiss the bride,’ the vicar added with a smile, and the Dame’s sister, Evie, duly uplifted her face to meet the lips of her new husband. She then turned round to find the Dame, and gave him an affectionate kiss on the cheek. ‘Thank you for giving me away,’ she said, her eyes shining.

‘My pleasure,’ he told her. She seemed as happy as he’d ever seen her, he thought, and hoped to God it would last. David Cross wasn’t the man he would have chosen for her, but he didn’t actually have anything specific against him. Yet.

The newly-weds were led off to sign the register, and the Dame walked out of the church with the best man to check that the photographer was ready. He was.

‘We haven’t seen you lately,’ a voice said in his ear.

He turned to find the vicar looking at him with that expression of pained concern which the Dame had always associated with people who were paid to care. ‘No, ’fraid not,’ he replied. ‘The call of duty,’ he explained with a smile.

The vicar examined the uniform which Evie had insisted her brother wear, his eyes coming to rest on the beige beret and its winged-dagger badge. ‘Well, I hope we see you again soon,’ he said.

The Dame nodded, and watched the man walk over to talk with his and Evie’s sister, Rosemary. A couple of years before, after the Colombian operation, he had started attending church regularly, this one here in Sunderland when he was at home, and another on the outskirts of Hereford during tours of duty. He could have used the Regimental chapel, but, without being quite sure why, had chosen to keep his devotions a secret from his comrades. It wasn’t that he feared they’d take the piss – though they undoubtedly would – it was just that he felt none of it had anything to do with anyone else.

He soon realized that this feeling encompassed vicars and other practising Christians, and in effect the Church itself. He stopped attending services, and started looking for other ways of expressing a yearning inside him which he could hardly begin to explain to himself, let alone to others. He wasn’t even sure it had anything to do with God – at least as other people seemed to understand the concept. The best he could manage by way of explanation was a feeling of being simultaneously drawn to something bigger than himself, something spiritual he supposed, and increasingly detached from the people around him.

The latter feeling was much in evidence at the wedding reception. It was good to see so many old friends: lads he’d been to school with, played football with, but none of them seemed to have much to say to him, and he couldn’t find much to say to them. A few old memories, a couple of jokes about Sunderland – town and football team – and that was about it. Most of them seemed bored with their jobs and, if they were married, bored with that too. They seemed more interested in one another’s wives than their own. The Dame hoped his sister…well, if David Cross cheated on her then the bastard would have him to deal with.

The time eventually arrived for the honeymooners’ departure, their hired car trailing its retinue of rattling tin cans. Soon after that, feeling increasingly oppressed by the reception’s accelerating descent into a drunken wife-swap, the Dame started off across the town, intent on enjoying the solitude of a twilight walk along the seafront.

It was a beautiful day still: cold but crystal-clear, gulls circling in the deepening blue sky, above the blue-grey waters of the North Sea. He walked for a couple of miles, up on to the cliffs outside the town, not really thinking about anything, letting the wind sweep the turmoil of other people from his mind.

He got back home to find his mother and Rosemary asleep in front of the TV, the living-room still littered with the debris of Christmas. On the table by the telephone there was a message for him to ring Hereford.

She sat with her knees pulled up to her chest, her head bowed down, on the stinking mattress in the slowly lightening room. The first night was over, she thought, but the first of how many?

The left side of her face still ached from where he had hit her, and the pain between her legs showed no signs of easing. She longed to be able to wash herself, and knew the longing was as much psychological as it was physical. Either way, she doubted if they would allow it.

This time yesterday, she thought, I was waiting for Hajrija in the nurses’ dormitory.

The previous morning, after the two Russians had been sent running back towards Sarajevo with their tails between their legs, the four Chetniks had simply abandoned their roadblock, as if it had accomplished its purpose. They had casually left the young American’s body by the side of the road, bundled her into the back seat of their Fiat Uno, and driven on down the valley to the next village. Here she could see no signs of the local population, either alive or dead, and only one blackened hulk of a barn bore testimony to recent conflict. As they pulled up in the centre of the village another group of Chetnik irregulars, a dozen or so strong, was preparing to leave in a convoy of cars.

The leader of her group exchanged a few pleasantries with the leader of the outgoing troops, and she was led into a nearby house, which, though stripped of all personal or religious items, had obviously once belonged to a Muslim family. Since their departure it had apparently served as a billet for pigs. The Chetniks’ idea of eating seemed to be to throw food at one another in the vain hope some of it went in through the mouth. Their idea of bathing was non-existent. The house stank.

What remained of the furniture was waiting to be burnt on the fire. And there was a large bloodstain on the rug in the main room which didn’t seem that old.

Nena was led through to a small room at the back, which was empty save for a soiled mattress and empty bucket. The only light filtered round the edges of the shutters on the single window.

‘I need to wash,’ she told her escort. They were the first words she had spoken since her abduction.

‘Later,’ he said. ‘There’s no need now,’ he added, and closed the door.

She had spent the rest of the day trying not to panic, trying to prepare herself for what she knew was coming. She wanted to survive, she kept telling herself, like a litany. If they were going to kill her anyway then there was nothing she could do about it, but she mustn’t give them an excuse to kill her in a fit of anger. She should keep her mouth shut, say as little as possible. Perhaps tell them she was a doctor – they might decide she could be of use to them.

The afternoon passed by, and the light faded outside. No one brought her food or water, but even above the sound of the wind she could hear people in the house and even smell something cooking. Eventually she heard the clink of bottles, and guessed that they had begun drinking. It was about an hour later that the first man appeared in the doorway.

In the dim light she could see he had a gun in one hand. ‘Take off the trousers,’ he said abruptly. She swallowed once and did as he said.

‘And the knickers.’

She pulled them off.

‘Now lie down, darling,’ he ordered.

She did so, and he was looming above her, dropping his jungle fatigues and long johns down to his knees, and thrusting his swollen penis between her legs.

‘Wider,’ he said, taking his finger off the gun’s safety-catch only inches from her ear.

He pushed himself inside her, and started pumping. He made no attempt to feel her breasts, let alone kiss her, and out of nowhere she found herself remembering her father’s dog, and its habit of trying to fuck the large cushion which someone had made for it to lie on. Now she was the cushion and this Serb was the dog. As smelly, as inhuman, as any dog.

He came with a furious rush, and almost leapt off her, as if she was suddenly contagious.

The second man was much the same, except for the fact that he didn’t utter a single word between entering the room and leaving it. Then there was a respite of ten minutes or so, before the group’s leader came in. He stripped from the waist down, grabbed a handful of her hair and lifted up her face to meet his own, as if determined to impress on her exactly who it was she was submitting to.

She let out an involuntary sob, and that seemed to satisfy him. He pushed inside her quickly, but then took his time, savouring the moment with slow, methodical strokes, stopping himself several times as he approached a climax, before finally letting himself slip over the edge.

The young one was last, and the other three brought him in like a bull being brought to a heifer. He couldn’t have been more than fourteen and he looked almost as nervous as he did excited. ‘Come on,’ the others said, ‘show her what you’ve got.’ He unveiled his penis almost shyly. It was already erect, quivering with anticipation.