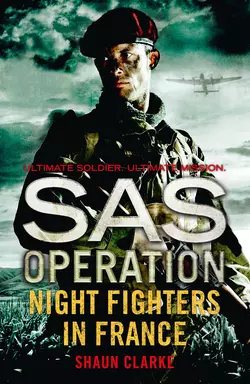

Night Fighters in France

Shaun Clarke

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 673.85 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But can the SAS distract the Nazis to allow airborne landings to go ahead?September 1944: in the wake of the successful ‘Anvil’ landings, the Allies plan airborne landings in the Orléans Gap. To ‘soften’ the enemy beforehand, they decide to drop a squadron of men and jeeps in Central France, to hit enemy positions to distract attention from the landings taking place elsewhereOperation Kipling begins when 46 jeeps and 107 well-armed SAS men from C Squadron are parachuted in with orders to establish a base and contact the Maquis – Frenchmen living in makeshift forest camps, conducting sabotage missions behind enemy lines.Even as they are setting up camp, the airborne landings are cancelled and the SAS ordered to conduct ‘aggressive’ patrolling. Over the coming weeks, C Squadron must carry out a succession of high risk night raids against the Germans, racing into occupied towns in jeeps, firing on the move, and racing out again: to continually harass the enemy and inflict heavy casualties. Or die trying.