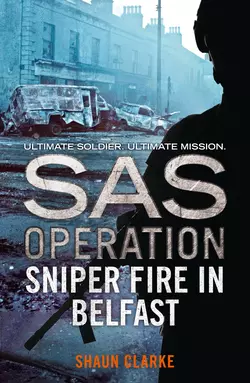

Sniper Fire in Belfast

Shaun Clarke

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But can the SAS survive working deep undercover among the terrorists of Northern Ireland?It is the 1970s, and a mean and dirty war is being waged on British soil. Sectarian violence is an almost daily occurrence and the terrorist groups, who finance their operations through robbery, fraud and extortion, engage in torture, assassination and wholesale slaughter.To cope with the terrorists’ activities the British Army need the support of exceptional soldiers who can operate deep undercover – the SAS. The regiment is soon embroiled in some of the most secretive, dangerous and controversial activities in its history. These include plain-clothes work in the towns and cities, the running of operational posts in rural areas, surveillance and intelligence gathering, ambushes and daring cross-border raids.Sniper Fire in Belfast is a nerve-jangling adventure about the most daring soldiers in military history, where friend and foe look the same and each encounter could be their last.

Sniper Fire in Belfast

SHAUN CLARKE

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1993

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1993

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © Alain le Garsmeur “The Troubles” Archive/Alamy (background); Shutterstock.com (soldier and textures)

Shaun Clarke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008154943

Ebook Edition © November 2015 ISBN: 9780008154950

Version: 2015-10-15

Contents

Cover (#ub0ea5bc4-4abb-5920-841c-24d8ae199084)

Title Page (#u8a172be7-4676-5f91-bb0c-b22288689782)

Copyright (#u449e01c3-bcc5-5483-987a-32e5673371ab)

Prelude (#u1bfd9e21-91be-5005-842c-d496324516c7)

Chapter 1 (#u8e0f20fd-74dc-5644-873f-70ef5d42a287)

Chapter 2 (#u194a7e99-ad10-5789-8e8f-046f75fb50bc)

Chapter 3 (#u8959700f-1771-5607-a125-d892cd8da58c)

Chapter 4 (#ua676c1a6-1809-5bb1-a730-920cf71d47e0)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prelude (#uf9f34f0b-ac0e-5cb8-96eb-379da35b3242)

Martin was hiding in a shallow scrape when they found him. He plunged into despair when he heard their triumphant shouting, then he was grabbed by the shoulders and jerked roughly up on to his knees.

The rain was lashing down over the wind-blown green fields, and he caught only a glimpse of the shadowy men in olive-green fatigues, carrying a variety of weapons and moving in to surround him, before he was blindfolded, bound by hands and feet, and thrown into the back of their truck like so much dead meat.

‘Face down in the fucking mud,’ one of them said, ‘digging through to Australia.’ The others laughed. ‘Looks a bit on the damp side, doesn’t he? That should save him embarrassment. We won’t notice the stains when the bugger starts pissing his pants – and that won’t take long, I’ll bet.’

Lying on his side on the floor of the truck, feeling the occasional soft kick from the boots of the men sitting above him, Martin had to choke back his panic and keep control of himself.

After so long, he thought. After so much. Don’t lose it all now …

The door on the driver’s side of the truck slammed shut, then the engine coughed into life and the vehicle rattled across the hilly terrain, bumped over what Martin judged to be the rough edge of the field, then moved straight ahead along a proper road. Still in despair, though knowing he hadn’t lost all yet, he took deep, even breaths, forcing his racing heart to settle down.

When someone’s body rolled into his and he heard a nervous coughing, he realized with a shameful feeling of relief that he wasn’t the only one they had caught.

‘Shit!’ he whispered.

‘What was that, boyo?’ one of his captors asked in a mocking manner. ‘Did I hear filthy language from down there?’

‘Take off this bloody blindfold,’ Martin said. ‘You don’t really need that.’

‘Feeling a bit uncomfortable, are you? A bit disorientated? Well, you better get used to it, you stupid prat, because that blindfold stays on. Now shut your mouth and don’t speak until you’re spoken to.’

The other tethered man rolled away from Martin, coughing uncomfortably. ‘We don’t have to…’ he began.

‘Put a sock in it,’ the same captor said, leaning down to roll the man over and somehow silence him. Even as Martin was wondering what the man was doing, a cloth was wrapped tightly around his mouth and tied in a knot at the back of his head. ‘Now you’re dumb as well as blind,’ the man said. ‘That should teach you not to open your trap when it’s not called for.’

‘Have you pissed your pants yet?’ another voice asked. ‘It’s hard to tell, you’re both so wet all over. Hope you’re not feeling cold, lads.’

Some of the men laughed. ‘Fucking SAS,’ another man said contemptuously. ‘Supposed to be impossible to find and these pricks lie there waiting to be picked up. If this is the best they can manage, they must be fit for the Girl Guides.’

The last remark raised a few more laughs and made Martin feel even worse, adding humiliation to his despair and increasing his fear of what might be to come.

You haven’t lost it all yet, he told himself. Just try to stay calm, in control. Don’t let them get to you. Don’t let fear defeat you.

It was easier to contemplate than it was to put into practice. Indeed, as the truck growled and shook beneath him, its hard boards seeming to hammer him, he became increasingly aware of his blindfold and gag, which in turn made him feel claustrophobic and unbearably helpless. As the blindfold was also covering his ears, he was practically deaf, dumb and blind. That forced him deeper into himself and made him strain to break out. This feeling was not eased by the cruel mockery of his captors as the truck growled and rattled along the road.

‘A big, brave British soldier?’ one of his captors said, prodding him in the ribs with his boot. ‘Found hiding face down in the mud. Not so big and brave now, boys.’

‘Might be big in unseen places. Might be brave with what’s hidden.’

‘That’ll be the day. A pair of English nancy boys. A pair of uniformed British poofters tryin’ to keep real men down. Well, when we get where we’re goin’, we’ll find out what they’re made of. I’m lookin’ forward to that.’

It’s not real, Martin thought, trying to stop himself from shivering, his soaked clothing starting to freeze and his exhaustion now compounded by despair at being caught. Bear in mind that nothing is real, that nothing can break you. Just don’t make a mistake.

After what seemed like an eternity, the truck came to a halt, the back was dropped down, and Martin was roughly hauled to his feet and dragged down to the ground, where they deliberately rolled him in the mud a few times, then stood him up in the wind and rain. Someone punched him lightly on the back of his neck, urging him forward. But as his ankles were still tethered together, allowing only minimal movement, they lost patience and two of them dragged him by the armpits across what seemed to be an open space – the wind was howling across it, lashing the rain into his face – then up steps, onto a porch. He heard doors squeaking open, felt warmer air reach his face, then was dragged in to where there was no wind or rain and the warmth was a blessing. His boots scraped over what seemed like linoleum, then they dragged him around a corner, along another straight stretch, then through another door – again he heard it squeaking as it opened – and at last pushed him down into a chair.

Stay calm, he thought desperately. Don’t make any mistakes. It all depends on what you say or don’t say, so don’t let them trick you. Don’t panic. Don’t break.

‘What a filthy specimen,’ someone said contemptuously. ‘He looks like he’s been taking a swim in his own piss and shit.’

‘Just mud and rain, sir,’ another man said. ‘Not the gentleman’s fault, his appearance. The natural elements, is all.’

‘Where did you find him?’

‘Belly down in the mud. Trying to blend in with the earth in the hope that we’d miss him. Fat chance of that, sir.’

‘The dumb British shit. He must think we’re all halfwits. Do we talk to him now or let him dry out?’

‘He won’t smell so bad when he dries out.’

‘That’s true enough. Hood him.’

The cloth was removed from Martin’s mouth, letting him breathe more easily. No sooner had he begun to do so than a hood was slipped over his head and tightened around his neck with a cord, making him feel even more claustrophobic. A spasm of terror whipped through him, then passed away again.

Breathe deeply and evenly, he thought. You’re not going to choke. They’re just trying to panic you.

‘My name is Martin Renshaw,’ he said, just to hear the sound of his own voice. ‘My rank is…’

A hand pressed over his mouth and pushed his head back until the hard chair cut painfully into his neck.

‘When we want your name, rank, serial number and date of birth we’ll ask for it,’ the colder voice said. ‘Don’t speak again unless spoken to. We’ll now leave you to dry out. Understood?’

Martin nodded.

‘That’s a good start. Now be a good boy.’

Their footsteps marched away, the door opened and slammed shut, then there was only the silence and his own laboured breathing. Soon he thought he could hear his heart beating, ticking off every second, every terrible minute.

As the hours passed he dried out, and his clothing became sticky, though it could have been sweat. Not knowing if it was one or the other only made him feel worse. His exhaustion, already considerable before his capture, was now attacking his mind. His thoughts slipped like faulty gears, his fear alternated with defiance, and when he started drifting in and out of consciousness it was only the cramp in his tightly bound arms that kept him awake.

He was slipping gratefully into oblivion when someone kicked his chair over. The shock was appalling, jolting him awake, screaming, though he didn’t hit the floor. Instead, someone laughed and grabbed the back of the chair to tip him upright again. The blood had rushed to his head and the panic had almost made him snap, but he took a deep breath and controlled himself, remembering that the hood was still over his head and that his feeling of suffocation was caused by that, as well as by shock.

‘So sorry,’ a man said, sounding terribly polite and English. ‘A little mishap. Slip of the foot. I trust you weren’t hurt.’

‘No,’ Martin said, shocked by the breathless sound of his own voice. ‘Could you remove this hood? Its really…’

The chair went over again and stopped just before hitting the floor. This time they held him in that position for some time, letting the blood run to his head, then tipped him upright again and let his breathing settle.

‘We ask the questions,’ the polite gentleman said, ‘and you do the answering. Now could you please tell us who else was with you in that field.’

Martin gave his name, rank, service number and date of birth.

The chair was kicked back, caught and tipped upright, then someone else bawled in Martin’s face: ‘We don’t want to know that!’

After getting his breath back, Martin gave his name, rank, service number and date of birth, thinking, This isn’t real.

It became real enough after that, with a wide variety of questions either politely asked or bawled, the polite voice alternating with the bullying one, and the chair being thrown back and jerked up again, but getting lower to the floor every time. Eventually, when Martin, despite his surging panic, managed to keep repeating only his name, rank, serial number and date of birth, they gave up on the chair and dragged him across the room to slam him face first into what seemed like a bare wall. There, the ropes around his ankles were released and he was told to spread his legs as wide as possible, almost doing the splits.

‘Don’t move a muscle,’ he was told by the bully.

He stood like that for what seemed a long time, until his thighs began to ache intolerably and his whole body sagged.

‘Don’t move!’ the bully screamed, slamming Martin’s face into the wall again and forcing him to straighten his aching spine. ‘Stay as still as the turd you are!’

‘We’re sorry to be so insistent,’ the polite one added, ‘but you’re not helping at all. Now, regarding what you were doing out there in the fields, do please tell us…’

It went on and on, with Martin either repeating his basic details or saying: ‘I cannot answer that question.’ They shouted, cajoled and bullied. They made him stand in one position until he collapsed, then let him rest only long enough to enable them to pick another form of torture that did not involve beating.

Martin knew what they were doing, but this wasn’t too much help, since he didn’t know how long it would last, let alone how long he might endure it. Being hooded only made it worse, sometimes making him feel that he was going to suffocate, at other times making him think that he was hallucinating, but always depriving him of his sense of time. It also plunged him into panics based solely on the fact that he no longer knew left from right and felt mentally and physically unbalanced.

Finally, they left him, letting him sleep on the floor, joking that they were turning out the light, since he couldn’t see that anyway. He lay there for an eternity – but perhaps only minutes – now yearning just to sleep, too tired to sleep, and whispering his name, rank, serial number and date of birth over and over, determined not to make a mistake when repeating it or, worse, say more than that. The only words he kept in mind other than those were: ‘I cannot answer that question.’ He had dreams – they may have been hallucinations – and had no idea of how long he had been lying there where they returned to torment him.

They asked Martin if he smoked and, when he said no, blew a cloud of smoke in his face. While he was coughing, they asked him more questions. When he managed, even through his delirium, to stick to his routine answers, one of them threw him back on the freezing floor and said: ‘Let’s feed the bastard to the dogs.’

They stripped off his clothing, being none too gentle, then left him to lie there, shivering with cold, almost sobbing, but controlling himself by endlessly repeating his name, rank, serial number and date of birth.

He almost lost control again when he heard dogs barking, snarling viciously, and hammering their paws relentlessly on the closed door.

Was it real dogs or a recording? Surely, they wouldn’t…Who? By now he was too tired to think straight, forgetting why he was there, rapidly losing touch with reality, his mind expanding and contracting, his thoughts swirling in a pool of light and darkness in the hood’s stifling heat.

A recording, was the thought he clung to. Must not panic or break.

The door opened and snarling dogs rushed in, accompanied by the shouting of men.

The men appeared to be ordering the dogs back out. When the dogs were gone, the door closed again.

Silence.

Then somebody screamed: ‘Where are you based?’

It was like an electric bolt shooting through Martin’s body, making him twitch and groan. He started to tell them, wanted to tell them, and instead said: ‘I cannot answer that question.’

‘You’re a good boy,’ the civilized English voice said. ‘Too stubborn for your own good.’

This time, when they hoisted him back on to the chair, he was filled with a dread that made him forget everything except the need to keep his mouth shut and make no mistakes. No matter what they said, no matter what they did, he would not say a word.

‘What’s the name of your squadron commander?’ the bully bawled.

‘I cannot answer that question,’ Martin said, then methodically gave his name, rank, serial number and date of birth.

The silence that followed seemed to stretch out for ever, filling Martin with a dread that blotted out most of his past. Eventually the English-sounding voice said: ‘This is your last chance. Will you tell us more or not?’

Martin was halfway through reciting his routine when they whipped off the hood.

Light blinded him.

1 (#uf9f34f0b-ac0e-5cb8-96eb-379da35b3242)

‘I still don’t think we should do it,’ Captain Dubois said, even as he hung his neatly folded OGs in his steel locker and started putting on civilian clothing. ‘It could land us in water so hot we’d come out like broiled chicken.’

‘We’re doing it,’ Lieutenant Cranfield replied, tightening the laces on his scuffed, black-leather shoes and oblivious to the fact that Captain Dubois was his superior officer, ‘I’m fed up being torn between Army Intelligence, MI6, the RUC and even the “green slime”,’ he said, this last being the Intelligence Corps. ‘If we come up with anything, as sure as hell one lot will approve, the other will disapprove, they’ll argue for months, and in the end not a damned thing will be done. Well, not this time. I’m going to take that bastard out by myself. As for MI5…’

Cranfield trailed off, too angry for words. After an uneasy silence, Captain Dubois said tentatively, ‘Just because Corporal Phillips committed suicide…’

‘Exactly. So to hell with MI5.’

Corporal Phillips had been one of the best of 14 Intelligence Company’s undercover agents, infiltrating the most dangerous republican ghettos of Belfast and collecting invaluable intelligence. A few weeks earlier he had handed over ten first-class sources of information to MI5 and within a week they had all been assassinated, one after the other, by the IRA.

Apart from the shocking loss of so many watchers, including Phillips, the assassinations had shown that MI5 had a leak in its system. That leak, as Cranfield easily discovered, was their own source, Shaun O’Halloran, who had always been viewed by 14 Intelligence Company as a hardline republican, therefore unreliable. Having ignored the advice of 14 Intelligence Company and used O’Halloran without its knowledge, MI5, instead of punishing him, had tried to save embarrassment by simply dropping him and trying to cover his tracks.

Cranfield, still shocked and outraged by the death of ten men, as well as the subsequent suicide of the conscience-stricken Phillips, was determined that their betrayer, O’Halloran, would not walk away scot-free.

‘A mistake is one thing,’ he said, placing his foot back on the floor and grabbing a grey civilian’s jacket from his locker, ‘but to believe that you can trust someone with O’Halloran’s track record is pure bloody stupidity.’

‘They weren’t to know that he was an active IRA member,’ Dubois said, studying himself in the mirror and seeing a drab civilian rather than the SAS officer he actually was. ‘They thought he was just another tout out to make a few bob.’

‘Right,’ Cranfield said contemptuously. ‘They thought. They should have bloody well checked.’

Though nervous about his famously short-fused SAS officer, Captain Dubois understood his frustration.

For the past year sharp divisions had been appearing between the two main non-military Intelligence agencies: MI6 (the secret intelligence service run by the Commonwealth and Foreign Office, never publicly acknowledged) and MI5, the Security Service openly charged with counter-espionage. The close-knit, almost tribal nature of the RUC, the Royal Ulster Constabulary, meant that its Special Branch was also running its own agents with little regard for Army needs or requirements. RUC Special Branch, meanwhile, was running its own, secret cross-border contacts with the Irish Republic’s Gardai Special Branch. Because of this complex web of mutually suspicious and secretive organizations, the few SAS men in the province, occupying key intelligence positions at the military HQ in Lisburn and elsewhere, were often exposed to internecine rivalries when trying to co-ordinate operations against the terrorists.

Even more frustrating was the pecking order. While SAS officers attempted to be the cement between mutually mistrustful allies, soldiers from other areas acted as Military Intelligence Officers (MIOs) or Field Intelligence NCOs (Fincos) in liaison with the RUC. Such men and women came from the Intelligence Corps, Royal Military Police, and many other sources. The link with each RUC police division was a Special Military Intelligence Unit containing MIOs, Fincos and Milos (Military Intelligence Liaison Officers). An MIO working as part of such a unit could find himself torn by conflicting responsibilities to the RUC, Army Intelligence and MI6.

That is what had happened to Phillips. Though formally a British Army ‘Finco’ answerable to Military Intelligence, he had been intimidated by members of the Security Service into routeing his information to his own superiors via MI5. In doing so he had innocently sealed his own fate, as well as the fate of his ten unfortunate informants.

No wonder Cranfield was livid.

Still, Dubois felt a little foolish. As an officer of the British Army serving with 14 Intelligence Company, he was Cranfield’s superior by both rank and position, yet Lieutenant Cranfield, one of a small number of SAS officers attached to the unit, ignored these fine distinctions and more or less did what he wanted. A flamboyant character, even by SAS standards, he had been in Northern Ireland only two months, yet already had garnered himself a reputation as a ‘big timer’, someone working out on the edge and possessed of extreme braggadocio, albeit with brilliant flair and matchless courage. While admiring him, for the latter qualities, Dubois was nervous about Cranfield’s cocksure attitude, which he felt would land him in trouble sooner or later.

‘We’ll be in and out in no time,’ Cranfield told him, clipping a holstered 9mm Browning High Power handgun to his belt, positioned halfway around his waist, well hidden by the jacket. ‘So stop worrying about it. Are you ready?’

‘Yes,’ Dubois said, checking that his own High Power was in the cross-draw position.

‘Right,’ Cranfield said, ‘let’s go.’

As they left the barracks, Dubois again felt a faint flush of humiliation, realizing just how much he liked and admired Cranfield and had let himself be won over by his flamboyance. Though a former Oxford boxing blue and Catholic Guards officer, Dubois was helplessly awed by the fact that his second-in-command, Lieutenant Randolph ‘Randy’ Cranfield, formerly of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the Parachute Regiment, had gone to Ampleforth where the founder of the SAS, David Stirling, had also been educated, and was widely admired for his daring – some would say reckless – exploits.

Dubois had his own brand of courage, which he had often displayed in the mean streets of Belfast or the ‘bandit country’ of Armagh, but he was basically conservative in outlook and helplessly admiring of those less inhibited. He had therefore gradually become Cranfield’s shadow, rather than his leader, and recognition of this fact made him uncomfortable.

They entered what looked like a normal army compound, surrounded by high walls of corrugated iron, with watch-towers and electronically controlled gates guarded on both sides with reinforced sangars. These stone walls were high because the IRA’s flavour of the month was the Russian-made RPG 7 short-range anti-tank weapon, which could hurl a rocket-propelled grenade in an arc with an effective range of 500 metres. With walls so high, however, the IRA would have to come dangerously close to the base before they could gain the required elevation for such an attack. The walls kept them at bay.

‘Another bleak day in Armagh,’ Cranfield said. ‘God, what I’d give for some sunshine and the taste of sangria!’

‘In January in Northern Ireland,’ Dubois replied, ‘I can’t even imagine that. But I know that I’d prefer the heat of Oman to this bloody place.’

‘Some of the others arriving next week have just come from there,’ Cranfield said, ‘which means they’ll be well blooded, experienced in desert survival, filled with the humane values of the hearts-and-minds campaign…’ – he paused for dramatic effect – ‘and completely out of sorts here.’

‘Yes,’ Dubois agreed glumly. ‘We’ll have to firm them up quickly. And being attached to us won’t make them too happy either. They’ll think they’ve been RTU’d back to the regular Army.’

‘They should be so lucky!’ Cranfield exclaimed, shaking his head and chuckling ruefully. ‘We should all be so lucky! Instead, we’re with 14 Intelligence Company, in the quicksand of too many conflicting groups. We’re neither here nor there, Jeremy.’

‘No, I suppose not.’

Though 14 Intelligence Company was a reconnaissance unit, it had been given the cover title, 4 Field Survey Troop, Royal Engineers, but was also known as the Northern Ireland Training and Tactics team. Located in the army compound Dubois and Cranfield were visiting, it was equipped with unmarked, civilian ‘Q’ cars and various non-standard weapons, including the Ingram silenced sub-machine-gun. The camp was shared with a British Army Sapper unit.

‘Look,’ Cranfield said impatiently as they crossed the parade ground, from the barracks to the motor pool, in the pearly-grey light of morning, ‘what we’re doing isn’t that unusual. I mean, six months ago we crossed the border to pick up an IRA commander and deposit him back in Northern Ireland, to be arrested by the RUC and brought to trial. Though a lot of people cried out in protest, that murderous bastard eventually got thirty years. Was it worth it or not?’

‘It was worth it,’ Dubois admitted, studying the low grey sky over the green fields of Armagh and longing for a holiday in the sun, as Cranfield had suggested.

‘Right,’ Cranfield said as they entered the busy motor pool, which reeked of petrol and was, as usual, filled with the roaring of engines being tested. ‘Since that damned power struggle between Five and Six, Major Fred has repeatedly crossed the border wearing dirty jeans, bearded, and carrying a false driving licence issued in Dublin. We’re not alone in this, Jeremy.’

‘Major Fred’ was an MI0 attached to Portadown Police HQ. Almost as disdainful of MI5 and MI6 as was Cranfield, he was also as daring in defying both of those organizations and going his own way. As the value of what he was doing had yet to be ascertained, Cranfield’s citing of him as an example of what was admirable in the muddy, dangerous waters of intelligence gathering in bandit country was in no way encouraging to Dubois.

‘I’m not interested in Major Fred,’ he said. ‘Let him worry the Portadown lot. I’m only interested in 14 Intelligence Company and how it might be adversely affected by what you’re planning to do.’

‘There won’t be any adverse effects. We’ve had those already. We can’t do any worse than ten murdered and one suicide. At the very least we’ll deny the IRA what they think is a propaganda victory. It’s not purely personal.’

I’ll bet, Dubois thought. ‘I just wish the ceasefire hadn’t ended,’ he said, not wanting his silence to reveal that he was actually nervous.

‘Why?’ Cranfield replied. ‘It was all nonsense anyway, inspired by the usual, idiotic rivalry between MI5 and MI6. I mean, what did it all amount to? During a raid on an IRA headquarters in Belfast, security forces discover a “doomsday” contingency plan for counter-attack on Protestant areas should there be a repetition of August ’69. Dismayed, the Foreign Office, including MI6, seeks a political solution that involves secret contacts with the IRA. The IRA plays along. As they do so, MI5 insist that the terrorists are merely seeking a breathing space. Knowledge of the doomsday plan then gives MI5 a perfect chance to discredit political contacts. Bingo! The ceasefire collapses and we’re back in business. Pull the plug on MI5 and we’d all live in a better world.’

They stopped by a red Morris Marina, one of the Q cars, equipped with a covert radio and modified to hide a wide variety of non-standard weapons and Japanese photographic equipment. Two British Army sergeants known to Dubois – both in civilian clothes – were leaning against the side of the car, smoking cigarettes. They straightened up when Dubois and Cranfield approached, though neither man saluted.

‘Sergeant Blake,’ Dubois said, nodding by way of welcome. ‘Sergeant Harris,’ He nodded in the direction of Cranfield. ‘This is Lieutenant Cranfield of the SAS, in charge of this mission.’

Both men nodded at Cranfield, neither saying a word.

‘You’ve been briefed?’ Cranfield asked.

‘Yes, sir,’ Sergeant Harris said. ‘We’re not bringing him back. It’s terminal. He stays where he lies.’

‘Correct,’ Cranfield said. ‘So let’s get going.’

Sergeant Harris was the driver, with Cranfield sitting in the front beside him. As Dubois took his seat in the back, beside Sergeant Blake, he thought of just how confused were the issues of this conflict and how easily men like Cranfield, even himself, could be driven to taking matters into their own hands, as they were doing right now.

Still, it had been a rather bad year: the humiliating fall of the Tory government; the creation of a non-elected, supposedly neutral power-sharing executive to replace direct rule of Ulster from London; the collapse of that executive under the intimidation of the Ulster Workers’ strike and IRA violence, including the horrendous Birmingham pub massacre; the Dublin bombing; an IRA truce through Christmas and New Year of 1974-5, and finally the collapse of that truce. Now the SAS was being officially brought in, hopefully to succeed where the regular Army had failed. Dubois was mildly offended.

Sergeant Harris started the car and headed away from the motor pool, driving past rows of Saracen armoured cars, troop trucks, tanks, as well as other Q cars, most of which were visibly well used. The road led around to where the Lynx, Wessex and Army Westland Scout helicopters were taking off and landing, carrying men to and from the many OPs, observation posts, scattered on the high, green hills of the province and manned night and day by rotating, regular army surveillance teams. It was a reminder to Dubois of just how much this little war in Northern Ireland was costing the British public in manpower and money.

‘I still don’t see why they had to bring in the SAS,’ he said distractedly as the Q car approached the heavily guarded main gate. ‘I mean, every Army unit in the province has Close Observation Platoons specially trained for undercover operations – so why an official, full complement of SAS?’

‘The main problem with your COPS,’ Cranfield replied, meaning the Close Observation Platoons, ‘is that the men simply can’t pass themselves off as Irishmen, and have, in fact, often got into trouble when trying to. Since our men are specially trained for covert operations, they can act as watchers without coming on with the blarney and buying themselves an early grave.’

There was more to it than that, as Dubois knew from his Whitehall contacts. The decision to send the SAS contingent had been taken by Edward Heath’s government as long ago as January 1974. The minority Labour government elected six weeks later – Harold Wilson’s second administration – was not informed when elements of B Squadron 22 SAS were first deployed to Northern Ireland at that time.

Unfortunately, on 26 January 1974, a former UDR soldier named William Black was shot and seriously wounded by security forces using a silenced sub-machine-gun. When Black was awarded damages, the SAS came under suspicion. The soldiers, not trained for an urban anti-terrorist role and fresh from the Omani desert, had not been made aware of the legal hazards of their new environment.

Worse was to come. B Squadron’s contingent was withdrawn abruptly from Ireland after two of its members attempted to rob a bank in Londonderry. Both men were later sentenced to six years’ imprisonment, though their just punishment hardly helped the image of the SAS, which was being viewed by many as a secret army of assassins, not much better than the notorious Black and Tans of old. Perhaps for this reason, the presence of the SAS in Ireland during that period was always officially denied.

Nevertheless, when Dubois had first arrived in the province to serve with 4 Field Survey Troop, he found himself inheriting SAS Lieutenant Randolph ‘Randy’ Cranfield as his deputy, or second-in-command. At first, Dubois and Cranfield had merely visited Intelligence officers in the Armagh area, including ‘Major Fred’ in Portadown, lying that they were under the direct orders of SIS (MI6) and Army HQ Intelligence staff. When believed by the naive, they asked for suggestions of worthwhile intelligence targets. This led them to make illicit expeditions across the border, initially just for surveillance, then to ‘snatch’ IRA members and return them at gunpoint to Northern Ireland to be ‘captured’ by the RUC and handed over for trial in the north. Now they were going far beyond that – and it had Dubois worried.

‘At least your lot have finally been committed publicly to Northern Ireland,’ he said to Cranfield as the car passed between the heavily fortified sangars on both sides of the electronically controlled gates. ‘That might be a help.’

‘It’s no more than a public relations campaign by the Prime Minister,’ Cranfield said with his customary cynicism as the car passed through the gates, which then closed automatically.

‘Paddy Devlin’s already described it as a cosmetic exercise, pointing out, accurately, that the SAS have always been here.’

That was true enough, Dubois acknowledged to himself. Right or wrong, the recent decision to publicly commit the SAS to Northern Ireland had been imposed by the Prime Minister without warning, even bypassing the Ministry of Defence. Indeed, as Dubois had learnt from friends, Home Secretary Merlyn Rees had already secretly confessed that it was a ‘presentational thing’, a melodramatic way of letting the public know that the most legendary group of soldiers in the history of British warfare were about to descend on Northern Ireland and put paid to the IRA.

‘What the Downing Street announcement really signalled,’ Dubois said, still trying to forget his nervousness, ‘was a change in the SAS role from intelligence gathering to combat.’

‘Right,’ Cranfield replied. ‘So don’t feel too bad about what we’re doing. Just think of it as legitimate combat. You’ll sleep easier that way.’

‘I hope so,’ Dubois said.

As the gates clanged shut behind the Q car, Sergeant Harris turned onto the road leading to the border, which was only a few miles from the camp. Once the grim, high walls of corrugated iron were out of sight, the rolling green hills came into view, reminding Dubois of how beautiful Northern Ireland was, how peaceful it always looked, away from the trouble spots.

This illusion of peace was rudely broken when his observant eye picked out the many overt OPs scattered about the hills, with high-powered binoculars and telescopes glinting under makeshift roofs of camouflaged netting and turf, constantly surveying the roads and fields. It was also broken when armoured trucks and tanks, bristling with weapons, trundled along the road, travelling between the border and the army camp.

After driving for about ten minutes they came to the British Army roadblock located two miles before the border. Sergeant Harris stopped to allow the soldiers, all wearing full OGs, with helmets and chin straps, and armed with SA-80 assanlt rifles, to show their papers. Presenting their real papers, as distinct from the false documents they were also carrying for use inside the Republic, they were waved on and soon reached the border. To avoid the Gardai – the police force of the Republic of Ireland – they took an unmarked side road just before the next village and kept going until they were safely over the border. Ten minutes later they came to a halt in the shady lane that led up to O’Halloran’s conveniently isolated farmhouse.

‘He can’t see us or hear from here,’ Cranfield said, ‘and we’re going the rest of the way by foot. You wait here in the car, Sergeant Harris. No one’s likely to come along here, except, perhaps, for some innocent local like the postman or milkman.’

‘And if he does?’

‘We can’t afford to have witnesses.’

‘Right, sir. Terminate.’

Cranfield glanced back over his shoulder at Captain Dubois, still in the rear seat. ‘Are you ready?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good, let’s go. You too, Sergeant Blake.’

Cranfield and Dubois unholstered their 9mm Browning High Power handguns as they got out of the car. Sergeant Blake withdrew a silenced L34A1 Sterling sub-machine-gun from a hidden panel beneath his feet and unfolded the stock as he climbed out of the car to stand beside the other two men. After releasing their safety-catches, the men walked up the lane, away from the Q car, until they arrived at the wooden gate that led into the fields surrounding the farmhouse.

It was not yet 8.30 a.m. and the sun was still trying to break through a thick layer of cloud, casting shadows over the misty green hills on all sides of the house. Birds were singing. The wind was moaning slightly. Smoke was rising from the chimney in the thatched roof, indicating that O’Halloran, known to live alone, was up and about.

His two Alsatians, tethered to a post in the front yard, hadn’t noticed the arrival of the men and were sleeping contentedly. The slightest sound, however, would awaken them.

Cranfield nodded at Sergeant Blake. The latter set his L34A1 to semi-automatic fire, leaned slightly forward with his right leg taking his weight and the left giving him balance, then pressed the extended stock of the weapon into his shoulder with his body leaning into the gun. He released the cocking handle, raised the rear assembly sight, then took careful aim. He fired two short bursts, moving the barrel right for the second burst, his body shaking slightly from the backblast. Loose soil spat up violently, silently, around the sleeping dogs, making them shudder, obscuring the flying bone and geyzering blood from their exploding heads. When the spiralling dust had settled down, the heads of the dogs resembled pomegranates. Blake’s silenced L34A1 had made practically no sound and the dogs had died too quickly even to yelp.

Using a hand signal, Cranfield indicated that the men should slip around the gate posts rather than open the chained gate, then cross the ground in front of the farmhouse. This they did, moving as quietly as possible, spreading out as they advanced with their handguns at the ready, merely glancing in a cursory manner at the Alsatians now lying in pools of blood.

When they reached the farmhouse, Cranfield nodded at Sergeant Blake, who returned the nod, then slipped quietly around the side of the house to cover the back door. When he had disappeared around the back, Cranfield and Dubois took up positions on either side of the door, holding their pistols firmly, applying equal pressure between the thumb and fingers of the firing hand.

Cranfield was standing upright, his back pressed to the wall. Dubois was on one knee, already aiming his pistol at the door. When the latter nodded, Cranfield spun around, kicked the door open and rushed in, covered by Dubois.

O’Halloran was sitting in his pyjamas at the kitchen table, about ten feet away, as the door was torn from its hinges and crashed to the floor. Shocked, he looked up from his plate, the fork still to his mouth, as Cranfield rushed in, stopped, spread his legs wide, and prepared to fire the gun two-handed.

‘This is for Phillips,’ Cranfield said, then fired the first shot.

O’Halloran jerked convulsively and slapped his free hand on the table, his blood already spurting over the bacon and eggs as his fork fell, clattering noisily on the tiles. He jerked again with the second bullet. Trying to stand, he twisted backwards, his chair buckling and breaking beneath him as he crashed to the floor.

Dubois came in after Cranfield, crouched low, aiming left and right, covering the room as Cranfield emptied his magazine, one shot after another in the classic ‘double tap’, though using all thirteen bullets instead of two.

O’Halloran, already dead, was jerking spasmodically from each bullet as Sergeant Blake, hearing the shots, kicked the back door in and rushed through the house, checking each room as he went, prepared to cut down anything that moved, but finding nothing at all. By the time he reached the kitchen at the front, the double tap was completed.

Sergeant Blake glanced at the dead man on the floor. ‘Good job, boss,’ he commented quietly.

‘Let’s go,’ Dubois said.

Cranfield knelt beside O’Halloran, placed his fingers on his neck, checked that he was dead, then stood up again.

‘Day’s work done,’ he said.

Unable to return Cranfield’s satisfied grin, though feeling relieved, Captain Dubois just nodded and led the three men out of the house. They returned to the Q car, not glancing back once, and let Sergeant Harris drive them away, back to Northern Ireland.

2 (#uf9f34f0b-ac0e-5cb8-96eb-379da35b3242)

Martin was leaning on the rusty railing when the ship that had brought him and the others from Liverpool inched into Belfast harbour in the early hours of the morning. His hair was longer than it should have been, windswept, dishevelled. He was wearing a roll-necked sweater, a bomber jacket, blue jeans and a pair of old suede boots, and carrying a small shoulder bag. The others, he knew, looked the same, though they were now in the bar, warming up with mugs of tea.

Looking at the lights beaming over the dark, dismal harbour, he was reminded of the brilliant light that had temporarily blinded him when the Directing Staff conducting the brutal Resistance to Interrogation (RTI) exercises had whipped the hood off his head. Later they had congratulated him on having passed that final hurdle even before his eyes had readjusted to the light in the bare, cell-like room in the Joint Services Interrogation Unit of 22 SAS Training Wing, Hereford. Even as he was being led from the room, knowing he would soon be bound for the last stages of his Continuation Training in Borneo, he had seen another young man, Corporal Wigan of the Light Infantry, being escorted out of the building with tears in his eyes.

‘He was the one you shared the truck with,’ his Director of Training had told him, ‘but he finally cracked, forgot where he was, and told us everything we wanted to know. Now he’s being RTU’d.’

Being returned to your unit of origin was doubly humiliating, first through the failure to get into the SAS, then through having to face your old mates, who would know you had failed. Even now, thinking of how easily it could have happened to him, Martin, formerly of the Royal Engineers, practically shuddered at the thought of it.

Feeling cold and dispirited by the sight of the bleak docks of Belfast, he hurried back into the bar where the other men, some recently badged like him, others old hands who had last fought in Oman, all of them in civilian clothing, were sipping hot tea and pretending to be normal passengers.

Sergeant Frank Lampton, who had been Martin’s Director of Training during the horrors of Continuation Training, was leaning back in his chair, wearing a thick overcoat, corduroy trousers, a tatty shirt buttoned at the neck, a V-necked sweater and badly scuffed suede shoes. With his blond hair dishevelled and his clothing all different sizes, as if picked up in charity shops, he did not look remotely like the slim, fit, slightly glamorous figure who had been Martin’s DT.

Sitting beside Sergeant Lampton was Corporal Phil Ricketts. Their strong friendship had been forged in the fierce fighting of the ‘secret’ war in Dhofar, Oman, in 1972. Ricketts was a pleasant, essentially serious man with a wife and child in Wood Green, North London. He didn’t talk about them much, but when he did it was with real pride and love. Unlike the sharp-tongued, ferret-faced Trooper ‘Gumboot’ Gillis, sitting opposite.

Badged with Ricketts just before going to Dhofar, Gumboot hailed from Barnstaple, Devon, where he had a wife, Linda, whom he seemed to hold in less than high esteem. ‘I was in Belfast before,’ he’d explained to Martin a few nights earlier, ‘but with 3 Para. When I returned home, that bitch had packed up and left with the kids. That’s why, when I was badged and sent back here, I was pleased as piss. I’ll take a Falls Road hag any day. At least you know where you stand with them.’

‘Up against an alley wall,’ Jock McGregor said.

Corporal McGregor had been shot through the hand in Oman and looked like the tough nut he was. Others who had fought with Lampton, Ricketts and Gumboot in Oman had gone their separate ways, with the big black poet, Trooper Andrew Winston, being returned there in 1975. A lot of the men had joked that the reason Andrew had been transferred to another squadron and sent back to Oman was that his black face couldn’t possibly pass for a Paddy’s. Whatever the true cause, he had been awarded for bravery during the SAS strikes against rebel strongholds in Defa and Shershitti.

Sitting beside Jock was Trooper Danny ‘Baby Face’ Porter, from Kingswinford, in the West Midlands. He was as quiet as a mouse and, though nicknamed ‘Baby Face’ because of his innocent, wide-eyed, choirboy appearance, was said to have been one of the most impressive of all the troopers who had recently been badged – a natural soldier who appeared to fear nothing and was ferociously competent with weapons. His speciality was the ‘double tap’ – thirteen rounds discharged from a Browning High Power handgun in under three seconds, at close range – which some had whispered might turn out useful in the mean streets of Belfast.

Not as quiet as Danny, but also just badged and clearly self-conscious with the more experienced troopers, Hugh ‘Taff’ Burgess was a broad-chested Welshman with a dark, distant gaze, a sweet, almost childlike nature and, reportedly, a violent temper when aroused or drunk. Throughout the whole SAS Selection and Training course Taff had been slightly slow in learning, very thorough at everything, helpful and encouraging to others, and always even-tempered. True, he had wrecked a few pubs in Hereford, but while in the SAS barracks in the town he had been a dream of good humour and generosity. Not ambitious, and not one to shine too brightly, he was, nevertheless, a good soldier, popular with everyone.

Last but not least was Sergeant ‘Dead-eye Dick’ Parker, who didn’t talk much. Rumour had it that he had been turned into a withdrawn, ruthless fighting machine by his terrible experience in the Telok Anson swamp in Malaya in 1958. According to the eye-witness accounts of other Omani veterans such as Sergeant Ricketts and Gumboot, Parker, when in Oman with them, had worn Arab clothing and fraternized mostly with the unpredictable, violent firqats, Dhofaris who had renounced their communist comrades and lent their support to the Sultan. Now, lounging lazily on a chair in blue denims and a tatty old ski jacket, he looked like any other middle-aged man running slightly to seed. Only his grey gaze, cold and ever shifting, revealed that he was alert and still potentially lethal.

The men were scattered all around the lounge, not speaking, pretending not to know one another. When the boat docked and the passengers started disembarking, they shuffled out of the lounge with them, but remained well back or took up positions on the open deck, waiting for the last of the passengers to disembark.

Looking in both directions along the quayside, Martin saw nothing moving among the gangplanks tilted on end, scattered railway sleepers and coils of thick mooring cables. The harbour walls rose out of the filthy black water, stained a dirty brown by years of salt water and the elements, supporting an ugly collection of warehouses, huts, tanks and prefabricated administration buildings. Unmanned cranes loomed over the water, their hooks swinging slightly in the wind blowing in from the sea. Out in the harbour, green and red pilot lights floated on a gentle sea. Seagulls circled overhead, crying keenly, in the grey light of morning.

Having previously been told to wait on the deck until their driver beckoned to them, the men did so. The last of the other passengers had disembarked when Martin, glancing beyond the quayside, saw a green minibus leaving its position in the car park. It moved between rows of empty cars and the trailers of articulated lorries, eventually leaving the car park through gates guarded by RUC guards wearing flak jackets and armed with 5.56mm Ruger Mini-14 assault rifles. When the minibus reached the quayside and stopped by the empty gangplank, Martin knew that it had to be their transport.

As the driver, also wearing civilian clothing, got out of his car, Sergeant Lampton made his way down the gangplank and spoke to him. The man nodded affirmatively. A group of armed RUC guards emerged from one of the prefabricated huts along the quayside to stand guard while the men’s bergen rucksacks were unloaded and heaped up on the quayside. There were no weapons; these would be obtained from the armoury in the camp they were going to. All of the men were, however, already armed with 9mm Browning High Power handguns, which they were wearing in cross-draw holsters under their jackets.

When the last of the bergens had been unloaded, Lampton turned back and waved the men down to the quayside. Martin went down between Ricketts and Gumboot, following the first into the back of the minibus, where a lot of the men were already seated. Gumboot was the last to get in. When he did so, one of the RUC guards slid the door shut and the driver took off, heading out into the mean streets of Belfast.

‘Can we talk at last?’ Gumboot asked. ‘I can’t stand this silence.’

‘Gumboot wants to talk,’ Jock McGregor said. ‘God help us all.’

‘He’s talking already,’ Ricketts said. ‘I distinctly heard him. Like a little mouse squeaking.’

‘Ha, ha. Merely attempting to break the silence, boss,’ retorted Gumboot, ‘and keep us awake until we basha down. That boat journey seemed endless.’

‘You won’t get to basha down until tonight, so you better keep talking.’

‘Don’t encourage him,’ Jock said. ‘It’s too early to have to listen to his bullshit. I’ve got a headache already.’

‘It’s the strain of trying to think,’ Gumboot informed him. ‘You’re not used to it, Jock.’

His gaze moved to the window and the dismal streets beyond, where signs saying NO SURRENDER! and SMASH SINN FEIN! fought for attention with enormous, angry paintings on the walls of buildings, showing the customary propaganda of civil war: clenched fists, hooded men clasping weapons, the various insignia of the paramilitary groups on both sides of the divide, those in Shankill, the Falls Road, and the grim, ghettoized housing estates of West Belfast.

‘How anyone can imagine this place worth all the slaughter,’ Taff Burgess said, studying the grim, wet, barricaded streets, ‘I just can’t imagine.’

‘They don’t think it’s worth it.’ Jock said. ‘They’re just a bunch of thick Paddies and murderous bastards using any excuse.’

‘Not quite true,’ Martin said. Brought up by strictly methodist parents in Swindon, not religious himself, but highly conscious of right and wrong, he had carefully read up on Ireland before coming here and was shocked by what he had learnt. ‘These people have hatreds that go back to 1601,’ he explained, ‘when the Catholic barons were defeated and Protestants from England arrived by boat to begin colonization and genocide.’

‘1601!’ Gumboot said in disgust. ‘The Paddies sure have fucking long memories.’

The Catholics were thrown out of their own land,’ Martin continued, feeling a little self-conscious. ‘When they returned to attack the Protestants with pitchforks and stones, the British hanged and beheaded thousands of them. Some were tarred with pitch and dynamite, then set on fire.’

‘Ouch!’ Taff exclaimed.

‘When the Catholics were broken completely,’ Martin continued in a trance of historical recollection, ‘their religion was outlawed, their language was forbidden, and they became untouchables who lived in the bogs below the Protestant towns. They endured that for a couple of hundred years.’

‘You’re still talking about centuries ago,’ Gumboot said. ‘That’s a long time to hold those old grudges. Might as well go back to the garden of Eden and complain that you weren’t given a bite of the fucking apple.’

‘It’s not the same thing,’ Martin insisted, feeling embarrassed that he was talking so much, but determined to get his point across. ‘We’re not talking about something that happened just once, centuries ago, but about something that’s never really stopped.’

‘So the poor buggers were thrown out of their homes and into the bogs,’ Taff Burgess said with genuine sympathy, his brown gaze focused inward. ‘So what happened next, then?’

‘Over the centuries, Belfast became a wealthy industrial centre, dominated entirely by Protestants. But the Catholics started returning to the city about 1800, and naturally, as they were still being treated like scum, they were resentful and struck back.’

‘Nothing like a bit of the old “ultra-violence” to get out your frustrations,’ said Gumboot, grinning wickedly. ‘Remember that film, A Clockwork Orange? Fucking good, that was.’

‘Race riots and pogroms became commonplace,’ Martin continued, now getting into his stride. ‘It burst out every five or six years, eventually leading to the formation of Catholic and Protestant militia. Civil war erupted in 1920. In 1921 the country was partitioned, with the six provinces of the North becoming a British statelet, ruled by its Protestant majority.’

‘Big fucking deal,’ Gumboot said as the minibus passed through a street of small terraced houses, many with their windows and doorways bricked up. Here the signs said: PROVOS RULE! and BRITS OUT! Even at this early hour of the morning there were gangs of scruffy youths on the street corners, looking for trouble. ‘What was so bad about that?’

‘Well, Catholics couldn’t get jobs and their slums became worse,’ Martin explained. ‘The electoral laws were manipulated to favour owners of property, who were mostly Protestants. Even after more riots in the thirties and forties, nothing changed. Finally, in 1969, the Catholics took to the streets again, where they were attacked by Protestant police and vigilantes. This time they refused to lie down and the whole city went up in flames.’

‘I remember that well,’ Jock said. ‘I saw it on TV. Mobs all over the place, thousands fleeing from their homes, and Army tanks in the streets. I could hardly believe what I was seeing. A civil war on British soil!’

‘Right,’ Ricketts chipped in. ‘And by the time they were done, you had Catholics on one side, Protestants on the other, and the British equivalent of the Berlin Wall between.’

He pointed out of the window of the van, where they could see the actual ‘Peace Line’: a fifteen-foot-high wall topped with iron spikes, cutting across roads, through rows of houses, and, as they had all been informed, right across the city.

‘Which led,’ Sergeant Lampton added laconically, ‘to the birth of the masked IRA terrorist and his opposite number, the loyalist terrorist in balaclava.’

‘And here we are, caught in the middle,’ Ricketts said, ‘trying to keep the peace.’

‘Trying to stay alive,’ Gumboot corrected him, ‘which is all it comes down to. I’ve only got one aim in this piss-hole – to make sure that none of the bastards on either side puts one in my back. Fuck all the rest of it.’

The minibus was now leaving the city to travel along the M1, through rolling hills which, Martin noticed, were dotted with British Army observation posts. Even as he saw the distant OPs, an AH-7 Lynx helicopter was hovering over one of them to insert replacements and take off the men already there. The OPs, Martin knew, were resupplied with men and equipment only by air – never by road.

‘Hard to believe that’s a killing ground out there,’ Sergeant Lampton said. ‘If it wasn’t for the OPs on the hills, it would all seem so peaceful.’

‘It looked peaceful in Oman as well,’ Ricketts said, ‘until the Adoo appeared. It’s the same with those hills – except instead of Adoo snipers, you have the terrorists. They look pretty serene from down here, but you’re right – those are killing fields.’

Martin felt an odd disbelief as he looked at the lush, serene hills and thought of how many times they had been used to hide torture and murder. That feeling remained with him when the minibus turned off the motorway and made its way along a winding narrow lane to the picturesque village of Bessbrook, where the British army had taken over the old mill. Located only four miles from the border, it was a village with a strongly Protestant, God-fearing community – there was not a single pub – and it was presently living through a grim spate of sectarian killings.

As revenge for the killing by Protestant terrorists of five local Catholics, a splinter group calling itself the South Armagh Republican Action Force had stopped a local bus and gunned down eleven men, most of them from Bessbrook, who were on their way home after work. Only one passenger and the Catholic driver had survived. Since that atrocity, both Protestant and Catholic ‘death squads’ had been stalking the countryside of south Armagh, killing people wholesale. It was this, Martin believed, that had prompted the British government to publicly commit the SAS to the area. Yet now, as the minibus passed through the guarded gates of the old mill, he could scarcely believe that this pretty village was at the heart of so many murderous activities.

‘OK,’ Sergeant Lampton said when the minibus braked to a halt inside the grounds of the mill. ‘The fun’s over. All out.’

The side door of the vehicle slid open and they all climbed out into the Security Forces (SF) base as the electronically controlled gates whined shut behind them. The mill had been turned into a grim compound surrounded by high corrugated-iron walls topped by barbed wire. The protective walls were broken up with a series of regularly placed concrete sentry boxes under sandbagged roofs and camouflaged netting. An ugly collection of Portakabins was being used for accommodation and administration. RUC policemen, again wearing flak jackets and carrying Ruger assault rifles, mingled with regular Army soldiers. Saracen armoured cars and tanks were lined up in rows by the side of the motor pool. Closed-circuit TV cameras showed the duty operator in the operations room precisely who was coming or going through the main gates between the heavily fortified sangars.

‘Looks like a fucking prison,’ Gumboot complained.

‘Home sweet home,’ Sergeant Lampton said.

3 (#uf9f34f0b-ac0e-5cb8-96eb-379da35b3242)

‘Settle down, men,’ Lieutenant Cranfield said when he had taken his place on the small platform in the briefing room, beside Captain Dubois and an Army sergeant seated at a desk piled high with manila folders. When his new arrivals had quietened down, Cranfield continued: ‘You men are here on attachment to 14 Intelligence Company, an intelligence unit that replaced the Military Reconnaissance Force, or MRF, of Brigadier Kitson, who was Commander of Land Forces, Northern Ireland, from 1970 to 1972. A little background information is therefore necessary.’

Some of the men groaned mockingly; others rolled their eyes. Grinning, Cranfield let them grumble for a moment, meanwhile letting his gaze settle briefly on familiar faces: Sergeants Lampton, Ricketts and Parker, as well as Corporal Jock McGregor and Troopers ‘Gumboot’ Gillis and Danny ‘Baby Face’ Porter, all of whom had fought bravely in Oman, before returning to act as Directing Staff at 22 SAS Training Wing, Hereford. There were also some recently badged new men whom he would check out later.

‘In March 1972,’ Cranfield at last began, ‘shortly after the Stormont Parliament was discontinued and direct rule from Westminster substituted, selected members of the SAS, mainly officers, were posted here as individuals to sensitive jobs in Military Intelligence, attached to units already serving in the province. Invariably, they found themselves in a world of petty, often lethal jealousies and division among conflicting agencies – a world of dirty tricks instigated by Military Intelligence officers and their superiors. The MRF was just one of those agencies, causing its own share of problems.’

Now Cranfield glanced at the newcomer, Martin Renshaw, who had endured Sergeant Lampton’s perfect impersonation of an Irish terrorist during the horrendous final hours of the RTI exercises during Continuation Training. What was more, he had done so without forgetting that it was only an exercise, unlike so many others, who were RTU’d as a result. According to his report, Renshaw was a serious young man with good technological training, pedantic tendencies, and heady ambitions.

‘As some of you have come straight from Oman,’ Cranfield continued, ‘it’s perhaps worth pointing out that certain members of the MRF were, like the firqats of Dhofar, former enemies who had been turned. Occasionally using these IRA renegades – known as “Freds” – as spotters, the MRF’s Q-car patrols identified many active IRA men and women, sometimes photographing them with cameras concealed in the boot of the car. Too often, however, MRF operations went over the top, achieving nothing but propaganda for the IRA.’

‘Just like the green slime,’ Gumboot said, copping some laughs from his mates and, as Cranfield noticed, a stony glance from his uneasy associate, the Army intelligence officer Captain Dubois.

‘Very funny, Trooper Gillis,’ Cranfield said. ‘Perhaps you’d like to step up here and take over.’

‘No, thanks, boss. Please continue.’

Cranfield nodded, secretly admiring Gumboot’s impertinence, which he viewed as a virtue not possessed by soldiers of the regular Army. ‘In 1972 a couple of embarrassing episodes led to the disbandment of Kitson’s organization. Number one was when a two-man team opened fire with a Thompson sub-machine-gun from a moving car on men standing at a Belfast bus stop. Though both soldiers were prosecuted, they claimed they’d been fired at first. The second was when the IRA assassinated the driver of an apparently innocuous laundry van in Belfast. This led to the revelation that the company that owned the van, the so-called Four Square Laundry, was actually an MRF front, collecting clothing in suspect districts for forensic examination.’

‘Proper dirty laundry,’ Jock McGregor said, winning a few more laughs.

‘Yes,’ Cranfield said, ‘it was that all right. Anyway, those two incidents caused a stir and brought an end to the MRF, which was disbanded early in 1973. But it soon became apparent that as the police, whether in or out of uniform, were soft targets for gunmen, a viable substitute for the MRF was required. This would require men who could penetrate the republican ghettos unnoticed, and who possessed keen powers of observation, quick wits, and even quicker trigger fingers.’

‘That’s us!’ the normally quiet Danny Porter, ‘Baby Face’, said with a shy grin.

‘Not at that time,’ Cranfield replied, ‘though certainly the training officer for the new team was then serving with 22 SAS. In fact, the new unit, formed at the end of 1973, was 14 Intelligence Company. While it was the job of that company to watch and gather information about the IRA, the SAS’s function was to act on the intelligence supplied by them and take action when necessary.’

‘Excuse me, boss,’ Taff Burgess asked, putting his hand in the air like an eager schoolboy. ‘Are you saying that 14 Intelligence Company never gets involved in overt action against the IRA? That they’ve never had, or caused, casualties?’

‘No. They have suffered, and have caused, casualties – but only when spotted and usually only when the terrorist has fired first. Their function is to gather intelligence – not to physically engage the enemy. That’s our job. To do it within the law, however, we have to know exactly who and what we’re involved with here in the province.’

Cranfield nodded at the Army sergeant standing beside the intelligence officer. The sergeant started distributing his manila folders to the SAS troopers sitting in the chairs. ‘The information I’m about to give you,’ Cranfield said, ‘is contained in more detail in those folders. I want you to read it later and memorize it. For now, I’ll just summarize the main points.’

He paused until his assistant, Sergeant Lovelock, had given out the last of the folders and returned to his desk.

‘At present there are fourteen British Army battalions in Northern Ireland, each with approximately 650 men, each unit deployed in its own Tactical Area of Responsibility, or TAOR, known as a “patch”. As the RUC’s B Special Reserve were highly suspect in the eyes of the Republicans, their responsibilities have been handed over to the Ulster Defence Regiment, a reserve unit composed in the main of local part-timers. Unfortunately the UDR is already deeply unpopular with the Catholics, who view its members as hard-line loyalists. Most Army commanders are no more impressed by the UDR, believing, like me, that it’s dangerous to let part-time Protestant reservists into hard Republican areas.’

‘Are they reliable otherwise?’ Ricketts asked.

‘Many of us feel that the Royal Ulster Constabulary is more reliable than the UDR, though we certainly don’t believe policemen are capable of taking complete charge of security. This is evidenced by the fact that RUC officers often refuse to accompany the Army on missions – either because they think it’s too risky or because they feel that their presence would antagonize the locals even more than the Army does.’

‘That sounds bloody helpful,’ Jock McGregor said sourly.

‘Quite. In fact, in strongly Republican areas the RUC have virtually ceded authority to us. They do, however, have two very important departments: the Criminal Investigations Department, or CID, in charge of interrogating suspects and gathering evidence after major incidents; and the Special Branch, or SB, which runs the informer networks vital to us all. They also have a Special Patrol Group, or SPG, with mobile anti-terrorist squads trained in the use of firearms and riot control. We can call upon them when necessary.’

‘What about the police stations?’ Lampton asked.

‘Sixteen divisions – rather like Army battalions – in total. Some are grouped into each of three specific regions – Belfast, South and North – each with an assistant chief constable in charge, with as much authority as the Army’s three brigadiers. Those three chief constables report in turn to the chief constable at RUC HQ at Knock, east Belfast.’

‘Who calls the shots?’ Jock McGregor asked.

‘The regular Army and UDR battalions are divided between three brigade HQs – 29 Brigade in the Belfast area, 8 Brigade in Londonderry and 3 Brigade in Portadown, the latter responsible for covering the border. The Brigade Commanders report to the Commander Land Forces, or CLF, at Lisburn, the top Army man in Ulster. He has to answer to the General Officer Commanding, or GOC, who, though an Army officer, is also in charge of the RAF and Royal Navy detachments in the province. He’s also responsible for co-ordination with the police and ministers. The HQNI, or Headquarters Northern Ireland, is located in barracks at Lisburn, a largely Protestant town just outside Belfast that includes the HQ of 39 brigade. Regarding the role of 14 Intelligence Company in all this, I’ll hand you over to Captain Dubois.’

Slightly nervous about talking to a bunch of men who would feel resentful about working with the regular Army, Captain Dubois coughed into his fist before commencing.

‘Good morning, gentlemen.’ When most of the Troop just stared steadily at him, deliberately trying to unnerve him, he continued quickly: ‘Like the SAS, 14 Intelligence Company is formed from soldiers who volunteer from other units and have to pass a stiff selection test. It recruits from the Royal Marines as well as the Army, though it looks for resourcefulness and the ability to bear the strain of long-term surveillance, rather than the physical stamina required for the Special Air Service.’

Applause, cheers and hoots of derision alike greeted Dubois’ words. Still not used to the informality of the SAS, he glanced uncertainly at Cranfield, who grinned at him, amused by his nervousness.

‘The unit has one detachment with each of the three brigades in Ulster,’ Dubois continued. ‘Each consists of twenty soldiers under the command of a captain. We operate under a variety of cover names, including the Northern Ireland Training Advisory Team, or NITAT, and the Intelligence and Security Group, or Int and Sy Group. Like the original MRF, most of our work involves setting up static OPs or the observation of suspected or known terrorists from unmarked Q cars. These have covert radios and concealed compartments for other weapons and photographic equipment. Most of the static OPs in Belfast are manned by our men and located in both Republican and Loyalist areas, such as Shankill, the Falls Road and West Belfast’s Turf Lodge and the Creggan. You men will be used mainly for OPs in rural areas and observation and other actions in Q cars here in Belfast. You will, in effect, be part of 14 Intelligence Company, doing that kind of work, initially under our supervision, then on your own.’

‘Armed?’ Danny Porter asked quietly.

‘Yes. With weapons small enough to be concealed. These include the 9mm Browning High Power handgun and, in certain circumstances, small sub-machine-guns.’

‘What’s our brief regarding their use?’

‘Your job is observation, not engagement, though the latter isn’t always avoidable. Bear in mind that you won’t be able to pass yourselves off as locals, eavesdropping in Republican bars or clubs. Try it and you’ll soon attract the curiosity of IRA sympathizers, some as young as fourteen, looking as innocent as new-born babies, but almost certainly in the IRA youth wing. If one of those innocents speaks to you, you can rest assured that he’ll soon be followed by a hard man of more mature years. Shortly after the hard man comes the coroner.’

Thankfully, the men laughed at Dubois’ sardonic remark, encouraging him to continue in a slightly more relaxed manner.

‘For that reason we recommend that you don’t leave your Q car unless absolutely necessary. We also recommend that you don’t try using an Irish accent. If you’re challenged, say no more than: “Fuck off!” And say it with conviction.’ When the men laughed again, Dubois said: ‘I know it sounds funny, but it’s actually the only phrase that might work. Otherwise, you cut out of there.’

‘At what point do we use our weapons?’ the new man, Martin Renshaw, boldly asked.

‘When you feel that your life is endangered and there’s no time to make your escape.’

‘Do we shoot to kill?’ ‘Baby Face’ asked.

‘Shooting to wound is a risky endeavour that rarely stops a potential assassin,’ Lieutenant Cranfield put in. ‘You shoot to stop the man coming at you, which means you can’t take any chances. Your aim is to down him.’

‘Which means the heart.’

‘Yes, Trooper.’

‘Is there actually a shoot-to-kill policy?’ Ricketts asked.

Captain Dubois smiled tightly. ‘Categorically not. Let’s say, instead, that there’s a contingency policy which covers a fairly broad range of options. I should remind you, however, that the IRA don’t always display our restraint. London’s policy of minimum fire-power, rejecting the use of ground- or air-launched missiles, mines, heavy machine-guns and armour, has contained the casualty figures to a level which no other government fighting a terrorist movement has been able to match. On the other hand, the Provisional IRA alone presently has at least 1200 active members and they’ve been well equipped by American sympathizers with a few hundred fully automatic 5.6mm Armalites and 7.62mm M60 machine-guns, as well as heavier weapons, such as the Russian-made RPG 7 short-range anti-tank weapon with rocket-propelled grenades. So let’s say we have reasonable cause to believe in reasonable force.’

‘Does reasonable force include the taking out of former IRA commanders?’ Sergeant ‘Dead-eye Dick’ Parker asked abruptly.

‘Pardon?’ Dubois asked, looking as shocked as Cranfield suddenly felt.

‘I’m referring to the fact that a few days ago a former IRA commander, Shaun O’Halloran, was taken out by an unknown assassin, or assassins, while sitting in his own home in the Irish Republic.’

Already knowing that his assassination of O’Halloran had rocked the intelligence community, as well as outraging the IRA, but not aware before now that it had travelled all the way back to Hereford, Cranfield glanced at Dubois, took note of his flushed cheeks, and decided to go on the attack.

‘Are you suggesting that the SAS or 14 Intelligence Company had something to do with that?’ he addressed Parker, feigning disbelief.

Parker, however, was not intimidated. ‘I’m not suggesting anything, boss,’ he replied in his soft-voiced manner. ‘I’m merely asking if such an act would be included under reasonable force?’

‘No,’ Captain Dubois intervened, trying to gather his wits together and take control of the situation. ‘I deny that categorically. And as you said, the assassin was unknown.’

‘The IRA are claiming it was the work of the SAS.’

‘The IRA blame us for a lot of things,’ Cranfield put in, aware that Parker was not a man to fool with.

‘Is it true,’ Ricketts asked, ‘that they also blame the SAS for certain actions taken by 14 Intelligence Company?’

When he saw Dubois glance uneasily at him, Cranfield deliberately covered his own temporary nervousness by smiling as casually as possible at Ricketts, who was, he knew, as formidable a soldier as Parker. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘that’s true. It’s a natural mistake to make. They know we’re involved in surveillance, so that makes us suspect.’

‘Who do you think was responsible for the assassination of O’Halloran?’

The questioner was Sergeant Parker again, studying Dubois with his steady, emotionless gaze. Dubois reddened and became more visibly flustered until rescued by Cranfield, who said: ‘O’Halloran’s assassination wasn’t in keeping with the psychological tactics employed by the Regiment in Malaya and Oman. More likely, then, it was committed by one of the paramilitary groups – possibly even the product of internal conflict between warring IRA factions. It certainly wasn’t an example of what the SAS – or 14 Intelligence Company – means by “reasonable force”.’

‘But the IRA,’ Parker went on in his quietly relentless way, ‘have hinted that O’Halloran may have been involved with a British army undercover agent, Corporal Phillips, who recently committed suicide for unexplained reasons.’

‘Corporal Phillips is believed to have been under considerable stress,’ Captain Dubois put in quickly, ‘which is not unusual in this line of business. May we go on?’

Sergeant Parker stared hard at the officer, but said no more.

‘Good,’ Dubois went on, determined to kill the subject. ‘Perhaps I should point out, regarding this, that while occasionally we may have to resort to physical force, only one in seven of the 1800 people killed in the Province have died at the hands of the security forces, which total around 30,000 men and women at any given time. I think that justifies our use of the phrase “reasonable force”.’

Dubois glanced at Lieutenant Cranfield, who stepped forward again.

‘We have it on the best of authority that the British government is about to abandon the special category status that’s allowed convicted terrorists rights not enjoyed by prisoners anywhere else in the United Kingdom. Under the new rules, loyalist and republican terrorists in the newly built H-blocks at the Maze Prison will be treated as ordinary felons. The drill parades and other paramilitary trappings that have been permitted in internment camps will no longer be allowed. This is bound to become a major issue in the nationalist community and increase the activities of the IRA. For that reason, I would ask you to remember this. In the past two decades the IRA have killed about 1800 people, including over a hundred citizens of the British mainland, about eight hundred locals, nearly three hundred policemen and 635 soldiers. Make sure you don’t personally add to that number.’

He waited until his words had sunk in, then nodded at Captain Dubois.

‘Please make your way to the motor pool,’ Dubois told the men. ‘There you’ll find a list containing the name of your driver and the number of your Q car. Your first patrol will be tomorrow morning, just after first light. Be careful. Good luck.’