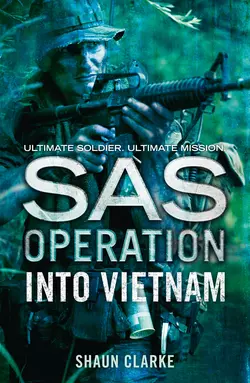

Into Vietnam

Shaun Clarke

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But will the SAS survive a nightmare journey into the tunnel lair of the Viet Cong?June 1966: 3 Squadron SAS (Australian Special Air Service) set up a Forward Operating Base in Vietnam’s Phuoc Tuy province, a swampy hell of jungle and paddy-fields forty-five miles east of Saigon in the heart of enemy territory. The Viet Cong have bases throughout the jungle, and the Australians soon find themselves under constant attack.Enter three members of the legendary 22 SAS, to assist in a major assault against the Viet Cong: Sergeant Jimmy ‘Jimbo’ Ashman, founding member of the Regiment; Sergeant Richard ‘Dead-eye Dick’ Parker, veteran of previous SAS operations in Malaya, Borneo and Aden; and Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick ‘Paddy’ Callaghan, pulled out of administration specially for this secret mission.Working under appalling conditions, Brits and Aussies must try to forge themselves into a potent fighting machine, as they have been tasked with the fearsome job of rooting the Viet Cong out of their labyrinthine tunnel system. It will be a journey into hell, and some will never return.

Into Vietnam

SHAUN CLARKE

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1995

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1995

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover photographs © MILpictures/Tom Weber/Getty Images (soldier); Shutterstock.com (textures)

Shaun Clarke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155421

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008155438

Version: 2015-11-02

Contents

Cover (#ud8f23448-1cd9-5f8d-81e2-aacf57cf032a)

Title Page (#u38196660-fb26-589a-80e0-f8b6eca32ec5)

Copyright (#u79282fa2-0f65-5e2d-adf9-3ffcf1b377b3)

Prelude (#u29926aea-fb78-5f91-9c9c-5576c0b805e2)

Chapter 1 (#u09b8c1f8-1392-595f-a1a4-128115d9b25d)

Chapter 2 (#ua6f32adf-86dc-5895-8967-6634946001c2)

Chapter 3 (#u0907df35-d7fa-53ef-9d41-4083be86c423)

Chapter 4 (#u367bb942-f3fa-5aff-859c-7e49daf0466a)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prelude (#u4d4a014a-9c1c-5d1a-98ac-07c92de41476)

The Viet Cong guerrillas emerged from the forest at dawn, with the mist drifting eerily about their heads. There were nearly fifty men, most dressed like coolies in black, pyjama-style combat gear and black felt hats, with sandals or rubber-soled boots on their feet. Nearly all of them were small and frail from lack of nourishment and years of fighting. Their weapons were varied: Soviet-made Kalashnikov AK47 machine-fed 7.62mm assault rifles; 7.62mm RPD light machine-guns with hundred-round link-belt drum magazines; 7.62mm PPS43 sub-machine-guns with a folding metal butt stock and thirty-five-round magazine; Soviet RPG7V short-range, anti-armour, rocket-propelled grenade launchers; and, for the officers only, Soviet Tokarev T33 7.62mm pistols, recoil-operated, semi-automatic and with an eight-round magazine.

As the VC left the forest behind them and crossed the paddy-field, wading ankle deep in water, the officers quietly slid their Tokarevs from their holsters and cocked them.

The Vietnamese hamlet was spread over a broad expanse of dusty earth surrounded by trees and its edge was about fifty yards beyond the paddy-field. With thatched huts, communal latrines, some cultivated plots, a regular supply of food from the nearby paddy-field, and a total of no more than fifty souls, it was exactly what the guerrillas were looking for.

Though this was an agricultural hamlet, the VC had been informed that the peasants had been trained by the CIA’s Combined Studies Division and Australian Special Air Service (SAS) teams in hamlet defence, including weapon training, moat and palisade construction, ambushing and setting booby-traps. The peasants were being armed and trained by the Americans in the hope that they would protect themselves against guerrilla attacks. What had been happening in practice, however, is that the VC, more experienced and in much greater numbers, had been destroying such hamlets and using the captured American arms and supplies against American and South Vietnamese forces elsewhere.

This was about to happen again.

The first to spot the VC were two peasants working at the far edge of the paddy-field. One of them glanced up, saw the raiding party and hastily waded out of the paddy-field and ran back to the hamlet. The second man was just about to flee when one of the VC officers fired at the first with his Tokarev.

The sound of that single shot was shockingly loud in the morning’s silence, making birds scatter from the trees to the sky, chickens squawk in panic, and dogs bark with the false courage of fear.

The 7.62mm bullet hit the man’s lower body, just beside the spinal column, violently punching him forward. Even as the first man was splashing face down in the water, the other man was rushing past him to get to dry land and the villagers were looking up in surprise. He had just reached the dry earth at the edge of the paddy-field when several VC fired at him with their AK47s, making him shudder like a rag doll, tearing him to shreds, then hurling him to the ground as the dust billowed up all around him.

A woman in the hamlet let out a long, piercing scream as the wounded man managed to make it to his knees, coughing water and blood from his lungs. Even as he was waving his arms frantically to correct his balance, pistols and assault rifles roared together. When he plunged backwards into the paddy-field, his clothes lacerated, the bullet holes pumping blood, wails of dread and despair arose from the hamlet.

While the women gathered their children around them and ushered them into the thatched houses, the men trained by the Americans rushed to take up positions in the defensive slit trenches armed with 7.62mm M60 GPMGs – general-purpose machine-guns. Others rushed to their thatched huts and emerged carrying L1A1 SLR semi-automatic rifles of the same calibre as the machine-guns. They threw themselves on the ground overlooking the moat filled with lethal punji stakes and wooden palisades constructed by Australian SAS troops, taking aim at the attackers. The VC were now emerging from the paddy-field and marching directly towards the minefield that encircled the hamlet.

Abruptly, the VC, who knew that the village was part of the US Strategic Hamlet Program and therefore well protected, split into three groups, two of which circled around the village, weaving through the palm trees just beyond the minefield. As they were doing so, the third group were taking positions in a hollow at the far side of the moat, between the paddy-field and the hamlet, and there setting up two Chinese 60mm mortars.

Realizing with horror that the two VC groups could only be circling around the back of the hamlet because they knew the location of the patrol route exit through the minefield; and that they were also going to mortar-bomb a way through the minefield at the front – information they must have obtained from an informer – some of the villagers opened fire with their rifles and GPMGs as others raced back across the clearing to stop the guerrillas getting in. This second group was, however, badly decimated when a third VC mortar fired half a dozen shells in quick succession, blowing the running men apart and then exploding in a broad arc that took in some of the surrounding thatched huts and set them ablaze.

As the flames burst ferociously from the thatched roofs and the wailing of women and children was heard from within, the first mortar shells aimed at the minefield exploded with a deafening roar. Soil, dust and smoke spewed skyward and then spread out to obscure the VC as some of them stood up and advanced at the crouch to the edge of the mined area. Kneeling there and checking where the mortars had exploded, the guerrillas saw that they nearly had a clear path and could complete the job with another few rounds.

Using hand signals, the leader of this group indicated a slightly lower elevation, then dropped to the ground as a hail of gunfire came from the frantic villagers at the other side of the minefield. When the second round of mortar shells had exploded, throwing up more billowing smoke and dust, the first of the VC advanced along the path of charred holes created by the explosions. That crudely cleared route led them safely through the minefield and up to the edge of the moat, where some of them were chopped down by the villagers’ guns and the rest threw themselves to the ground to return fire.

By now the other two groups of VC had managed to circle around to the back of the hamlet and, using the map given to them by the informer, had located the patrol route exit and started moving carefully along it in single file. Almost instantly, the first of them were cut down by the few armed peasants who had managed to escape the mortars exploding in the centre of the hamlet. As the first of the VC fell, however, the rest opened fire with their AK47s, felling the few peasants who had managed to get this far. The rest of the guerrillas then raced along the patrol route exit, into the centre of the hamlet, where, with the screams and weeping of women and children in their ears, they were able to come up behind the villagers defending the moat to the front.

Some of the women kneeling in the clearing in front of their burning homes cried out warnings to their men, but it was too late. Caught in a withering crossfire from front and rear, the villagers firing across the moat, among them a few teenage girls, were chopped to pieces and died screaming and writhing in a convulsion of spewing soil and dust. Those who did not die immediately were put to death by the bayonet. When their mothers, wives or children tried to stop this, they too were dispatched in the same way. Within minutes the attack was over and the remaining VC were wading across the moat and clambering up to the clearing.

In a state of shock and grief, and surrounded by their dead relatives and friends, the rest of the villagers were easily subdued and forced to kneel in the middle of the clearing. The remaining thatched huts were then searched by the guerrillas and those inside prodded out at bayonet or gun point. After a rigorous interrogation – faces were slapped and lots of insults were shouted, though no other form of torture was used – the villagers considered to be ‘traitors’ to the communists were led away and made to kneel by the moat. There they were shot, each with a single bullet to the back of the head, then their bodies were kicked over the edge into the water.

When this grisly operation was over, the rest of the villagers, many in severe shock, were forced into separate work groups. One of these, composed only of men and teenage boys, was made to drag the dead bodies out of the moat with meat-hooks, then place them on ox carts and take them to a cleared area just outside the perimeter, where they were buried without ceremony in a shallow pit.

When, about three hours later, this work party, now exhausted and in an even worse state of shock, returned to the hamlet, they found their friends already at work clearing away the burnt-out dwellings and unwanted foliage with machetes, hoes, short-handled spades and buckets under the impassive but watchful gaze of armed VC guards. Assigned their individual tasks in this joint effort, they began with the others what would be weeks of hard, nightmarish, ingenious work: the construction of an elaborate tunnel system directly under the devastated hamlet.

First, a series of large, rectangular pits, each about fifteen feet deep, was dug on the sites of the destroyed huts. Over these pits were raised sloping thatched roofs of the type found on the other dwellings, though the newly built roofs were mere inches off the ground. Viewed from the air, they would suggest normal hamlet houses.

Once the thatched roofs had been raised, work began on digging a series of tunnels leading down from the floor of each pit. Most of these were so narrow that there was only enough space for a single, slim body to wriggle along them, and in places they descended vertically, like a well, before continuing at a gentler slope in one direction or another. The only tunnel not beginning in one of the pits and not making any kind of bend was a well, its water table about forty feet deep and its surface access, level with the ground, camouflaged with a web of bamboo covered with soil and shrubbery.

One of the pits served as a kitchen, complete with bamboo shelves and a stone-walled stove. Smoke was vented into a pipe that spewed it into a tunnel running about eight feet underground until it was 150 feet west of the kitchen, where it emerged through three vents hidden in the palm trees beyond the perimeter.

An escape tunnel descended from the floor of the kitchen, curving west and crossing two concealed trapdoors before dividing into two even narrower tunnels. One of these was a false tunnel that led to a dead end; the other, concealed, rose steeply until it reached an escape hole hidden in the trees beyond the smoke outlets. A third escape tunnel, hidden by a concealed trapdoor, led away from the tunnel complex but linked up with another under the next village to the west. Of the other two trapdoors in this escape route, one had to be skirted, as the weight of a human body would make it collapse and drop that person to a hideous death in a trap filled with poisoned punji stakes. The third concealed trapdoor ran down into a large cavern hacked out of the earth about thirty feet down, to be used as a storage area for weapons, explosives and rice.

A short tunnel running east from the entrance to the underground storage area led into the middle of the well, about halfway down. On the opposite side of the well, but slightly lower, where the man pulling water up with a bucket and rope could straddle both ledges with his feet, another tunnel curved up and levelled out. At that point there was another trapdoor, and this covered a tunnel that climbed vertically to the floor of a conical air-raid shelter, so shaped because it amplified the sound of approaching aircraft and therefore acted as a useful warning system.

Leading off the air-raid shelter was another tunnel curving vertically until it reached the conference chamber. Complete with long table, wooden chairs and blackboard, the conference chamber was located in another of the pits, under a thatched roof almost touching the ground.

A narrow airing tunnel led from the pyramidal roof of the air-raid shelter to the surface; another led down to where the tunnel below levelled out and ran on to a second dead end, but one with another trapdoor in the floor. This trapdoor, proof against blast, gas and water, covered a tunnel that dropped straight down before curving around and up again in a series of loops that formed a natural blast wall. The top of this tunnel was sealed off by a second, similarly protective trapdoor, located in another cavernous area hacked out of the earth about fifteen feet down.

Though this cavernous area was empty – its only purpose to allow gas to dissipate and water to drain away – a series of interlinking access and exit tunnels ran off it. One led even deeper, to a large, rectangular space that would be used as the forward aid station for the wounded. The escape tunnel leading from this chamber ran horizontally under the ground, about twenty-five feet down, parallel to the surface, until it reached the similar network of tunnels under the next hamlet to the east.

The tunnel ascending to the east of the empty cavern led to another concealed trapdoor and two paths running in opposite directions: one to a camouflaged escape hole, the other to another pit dug out of the ground, this one not covered with a decoy thatched roof, but camouflaged with foliage and used as a firing post for both personal and anti-aircraft weapons.

West of this firing post, and similarly camouflaged, was a ventilation shaft running obliquely down to the empty cavern over the tunnel trap used as a natural blast wall. West of this ventilation shaft was the first of a series of punji pits, all camouflaged. West of the first punji pit was another concealed, ground-level trapdoor entrance that led into another tunnel descending almost vertically to a further hidden trapdoor.

Anyone crawling on to this last trapdoor would find it giving way beneath them and pitching them to their death on the sharpened punji stakes below. However, anyone skirting the trapdoor and crawling on would reach the biggest chamber of them all – the VCs’ sleeping and living quarters, with hammock beds, folding chairs and tables, stone chamber pots, bamboo shelves for weapons and other personal belongings, and all the other items that enable men to live for long periods like rats underground.

After weeks of hard labour by both South Vietnamese peasants and VC soldiers, this vast complex of underground tunnels was complete and some of the peasants were sent above ground to act as if the hamlet were running normally. Though still in a state of shock at the loss of friends, relatives and livelihood, the peasants knew that they were being watched all the time and would be shot if they made the slightest protest or tried to warn those defending South Vietnam.

Those peasants still slaving away in the tunnel complex would remain there to complete what would become in time four separate levels similar to the one they had just constructed. The levels would be connected by an intricate network of passages, some as narrow as eighty centimetres, with ventilation holes that ran obliquely to prevent monsoon rain flooding and were orientated so as to catch the morning light and bring in fresh air from the prevailing easterly winds.

The guerrillas not watching the peasants were living deep underground, existing on practically nothing, constantly smelling the stench of their own piss and shit, emerging from the fetid chambers and dank tunnels only when ordered to go out and strike down the enemy. Like trapdoor spiders, they saw the light of day only when they brought the darkness of death.

1 (#u4d4a014a-9c1c-5d1a-98ac-07c92de41476)

The swamp was dark, humid, foul-smelling and treacherous. Wading chest deep in the scum-covered water, Sergeant Sam ‘Shagger’ Bannerman and his sidekick, Corporal Tom ‘Red’ Swanson, both holding their jungle-camouflaged 7.62mm L1A1 self-loading rifles above their heads, were being assailed by mosquitoes, stinging hornets and countless other crazed insects. After slogging through the jungle for five days, they were both covered in bruises and puss-filled stings and cuts, all of which drove the blood lust of their attackers to an even greater pitch.

‘You try to talk…’ Red began, then, almost choking on an insect, coughed and spat noisily in an attempt to clear his throat. ‘You try to talk and these bloody insects fly straight into your mouth. Jesus Christ, this is terrible!’

‘No worse than Borneo,’ Sergeant Bannerman replied. ‘Well, maybe a little…’

In fact, it was worse. Shagger had served with 1 Squadron SAS (Australian Special Air Service) of Headquarters Far East Land Forces during the Malaya Emergency in 1963. In August of that year he had joined the Training Team in Vietnam, and from February to October 1964 had been with the first Australian team to operate with the US Special Forces at Nha Trang. Then, in February 1966, he was posted with 1 Squadron SAS to Sarawak, Borneo, and spent two months there before being recalled, along with a good half of 1 Squadron, to the SAS headquarters at Swanbourne, Perth, for subsequent transfer to 3 Squadron SAS, training especially for the new Task Force in Vietnam. They had not yet reached ’Nam, but would certainly be there soon, once they had completed this business in the hell of New Guinea. Shagger had indeed seen it all – and still he thought this was bad.

‘Not much longer to go,’ he said, still wading waist deep in the sludge and finding it difficult because the bed of the swamp was soft and yielding, being mainly a combination of mud and small stones but dangerously cluttered with larger stones, fallen branches and other debris. The task of wading on this soft bottom was not eased by the fact that Shagger and Red were both humping 90lb of bergen rucksack and 11lb of loaded SLR semiautomatic assault rifle. The problems were further compounded by the knowledge that the surface of the water was covered with a foul-smelling slime composed of rotted seeds, leaves and moss. It was also cluttered with obstructions that included giant razor-edged palm leaves and floating branches, the latter hard to distinguish from the highly venomous sea-snakes that infested the place. If these weren’t bad enough, there were other snakes in the branches that overhung the swamp, brushing the men’s heads, as well as poisonous spiders and bloodsucking leeches. So far, while neither soldier had been bitten by a venomous sea-snake or spider, both had lost a lot of blood to the many leeches that attached themselves to their skin under the water or after falling from the branches or palm leaves above them.

‘My eyes are all swollen,’ Red complained. ‘I can hardly see a thing.’

‘Your lips are all swollen as well,’ Shagger replied, ‘but you still manage to talk.’

‘I’m just trying to keep your pecker up, Sarge.’

‘With whinges and moans? Just belt up and keep wading. We’ll get there any moment now and then you can do a bit of spine bashing’ – he meant have a rest – ‘and tend to your eyes and other swollen parts, including your balls – if you’ve got any, that is.’

‘I don’t remember,’ Red said with feeling. ‘My memory doesn’t stretch back that far.’ He had served with Shagger in Borneo, and formed a solid friendship that included a lot of banter. He felt easy with the man. But then, having a philosophical disposition, he rubbed along with most people. ‘Actually,’ he said, noticing with gratitude that the water was now below his waist, which meant they were moving up on to higher ground, ‘I prefer this to Borneo, Sarge. I couldn’t stand the bridges in that country. No head for heights, me.’

‘You did all right,’ Shagger said.

In fact, Red had been terrific. Of all the many terrifying aspects of the campaign in Borneo, the worst was crossing the swaying walkways that spanned the wide and deep gorges with rapids boiling through bottlenecks formed by rock outcroppings hundreds of feet below. Just as in New Guinea, the jungles of Borneo had been infested with snakes, lizards, leeches, wild pigs, all kinds of poisonous insects, and even head-hunters, making it a particularly nightmarish place to fight a war. And yet neither snakes nor head-hunters were a match for the dizzying aerial walkways when it came to striking terror into even the most courageous men.

The walkways were crude bridges consisting of three lengths of thick bamboo laid side by side and strapped together with rattan – hardly much wider than two human feet placed close together. The uprights angled out and in again overhead, and were strapped with rattan to the horizontal holds. You could slide your hands along the holds only as far as the next upright. Once there, you had to remove your hand for a moment and lift it over the upright before grabbing the horizontal hold. All the time you were doing this, inching forward perhaps 150 feet above a roaring torrent, the narrow walkway was creaking and swinging dangerously in the wind that swept along the gorge. It was like walking in thin air.

Even worse, the Australians often had to use the walkways when they were making their way back from a jungle patrol and being pursued by Indonesian troops. At such times the enemy could use the walkways as shooting galleries in which the Aussies made highly visible targets as they inched their way across.

This had been the experience of Shagger and Red during their last patrol before returning to Perth. Their patrol had been caught in the middle of an unusually high walkway, swaying over rapids 160 feet below, while the Indonesians unleashed small-arms fire on them, killing and wounding many men, until eventually they shot the rattan binding to pieces, making the walkway, with some unfortunates still on it, tear away from its moorings, sending the men still clinging to it screaming to their doom.

Shagger, though more experienced than Red, had suffered nightmares about that incident for weeks after the event, but Red, with his characteristic detachment, had only once expressed regret at the loss of his mates and then put the awful business behind him. And though, as he claimed, he had no head for heights, he had been very courageous on the walkways, often turning back to help more frightened men across, even in the face of enemy fire. He was a good man to have around.

‘The ground’s getting higher,’ Shagger said, having noticed that the scummy water was now only as high as his knees. ‘That means we’re heading towards the islet marked on the map. That’s our ambush position.’

‘You think we’ll get there before they do?’ Red asked.

‘Let us pray,’ Shagger replied.

As he waded the last few hundred yards to the islet, now visible as a mound of firm ground covered with seedlings and brown leaves, with a couple of palm trees in the middle, Shagger felt the exhaustion of the past five days falling upon him. Three Squadron SAS had been sent to New Guinea to deploy patrols through forward airfields by helicopter and light aircraft; to patrol and navigate through tropical jungle and mountain terrain; to practise communications and resupply; and to liaise with the indigenous people.

For the past five days, therefore, the SAS men had sweated in the tropical heat; hacked their way through seemingly impassable secondary jungle with machetes; climbed incredibly steep, tree-covered hills; waded across rivers flowing at torrential speeds; oared themselves along slower rivers on ‘gripper bar’ rafts made from logs and four stakes; slept in shallow, water-filled scrapes under inadequate ponchos in fiercely driving, tropical rainstorms; suffered the constant buzzing, whining and biting of mosquitoes and hornets; frozen as poisonous snakes slithered across their booted feet; lost enormous amounts of blood to leeches; had some hair-raising confrontations with head-hunting natives – and all while reconnoitring the land, noting points of strategic value, and either pursuing, or being pursued by, the enemy.

Now, on the last day, Shagger and Red, having been separated accidentally from the rest of their troop during a shoot-out with an enemy column, were making their way to the location originally chosen for their own troop as an ambush position, where they hoped to have a final victory and then get back to base and ultimately Australia. After their long, arduous hike through the swamp they were both exhausted.

‘I’m absolutely bloody shagged,’ Red said, gasping. ‘I can hardly move a muscle.’

‘We can take a rest in a minute,’ Shagger told him. ‘Here’s our home from home, mate. The ambush position.’

The islet was about fifty yards from the far edge of the swamp they had just crossed, almost directly facing a narrow track that snaked into the jungle, curving away out of sight. It was along that barely distinguishable track that the enemy would approach on their route across the swamp, but in the opposite direction as they searched for Shagger’s divided patrol, which had undoubtedly been sighted by one of their many reconnaissance helicopters.

Wading up to the islet, pushing aside the gigantic, bright-green palm leaves that floated on its miasmal surface, Shagger and Red finally found firm ground beneath them and were able to lay down their SLRs and shrug off their heavy bergens. Relieved of that weight, they clambered up on to the islet’s bed of brown leaves and seedlings, rolled on to their backs and gulped in lungfuls of air. Both men did a lot of deep breathing before talking again.

‘Either I’m gonna flake out,’ Red finally gasped, ‘or I’m gonna have a good chunder. I feel sick with exhaustion.’

‘You can’t sleep and you can’t chuck up,’ Shagger told him. ‘You can chunder when you get back to base and have a skinful of beer. You can sleep there as well. Right now, though, we have to dig in and set up, then spring our little surprise. Those dills, if they get here at all, will be here before last light, so we have to be ready.’

‘Just let me have some water’, Red replied, ‘and I’ll be back on the ball.’

‘Go on, mate. Then let’s get rid of these bloody leeches and prepare the ambush. We’ll win this one, Red.’

When they had quenched their thirst, surprising themselves by doing so without vomiting, they lit cigarettes, inhaled luxuriously for a few minutes, then proceeded to burn off, with their cigarettes, the leeches still clinging to their bruised and scarred skin. As they were both covered with fat, black leeches, all still sucking blood, this operation took several cigarettes. When they had got rid of the bloodsuckers they wiped their skins down with antiseptic cream and set about making a temporary hide.

The islet was an almost perfect circle hardly more than thirty feet in diameter. The thick trees soaring up from the carpet of seedlings and leaves were surrounded by a convenient mass of dense foliage over which the branches draped their gigantic palm leaves. As this natural camouflage would give good protection, Shagger chose this area for the location of the hide and he and Red then dug out two shallow lying-up positions, or LUPs, using the small spades clipped to their webbing.

This done, each man began to construct a simple shelter over his LUP by driving two V-shaped wooden uprights into the soft soil, placed about six feet apart. A length of nylon cord was tied between the uprights, then a waterproof poncho was draped over the cord with the long end facing the prevailing wind and the short, exposed end, facing the path at the far side of the swamp. The two corners of each end were jerked tight and held down with small wooden pegs and nylon cord. The LUP was then filled with a soft bed of leaves and seedlings, a sleeping-bag was rolled out on to it, and the triangular tent was carefully camouflaged with giant leaves and other foliage held down with fine netting.

Once the shelters had been completed, the hide blended in perfectly with the surrounding vegetation, making it practically invisible to anyone coming along the jungle track leading to the swamp.

‘If they come out of there,’ Shagger said with satisfaction, ‘they won’t have a prayer. Now let’s check our kit.’

The afternoon sun was still high in the sky when each man checked his SLR, removing the mud, twigs, leaves and even cobwebs that had got into it; oiling the bolt, trigger mechanism and other moving parts; then rewrapping it in its jungle-coloured camouflage material. Satisfied that the weapons were in working order, they ate a cold meal of tinned sardines, biscuits and water, battling every second to keep off the attacking insects. Knowing that the enemy trying to find them would attempt to cross the swamp before the sun had set – which meant that if they came at all, they would be coming along the track quite soon – they lay on their bellies in their LUPs, sprinkled more loose foliage over themselves as best they could, and laid the SLRs on the lip of their shallow scrapes, barrels facing the swamp. Then they waited.

‘It’s been a long five days,’ Shagger said.

‘Too bloody long,’ Red replied. ‘And made no better by the fact that we’re doing the whole thing on a shoestring. Piss-poor, if you ask me.’

Shagger grinned. ‘The lower ranks’ whinge. How do you, a no-hoper corporal, know this was done on a shoestring?’

‘Well, no RAAF support, for a start. Just that bloody Ansett-MAL Caribou that was completely unreliable…’

‘Serviceability problems,’ Shagger interjected, still grinning. ‘But the Trans Australian Airlines DC3s and the Crowley Airlines G13 choppers were reliable. They made up for the lack of RAAF support, didn’t they?’

‘You’re joking. Those fucking G13s had no winch and little lift capability. They were as useless as lead balloons.’

‘That’s true,’ Shagger murmured, recalling the cumbersome helicopters hovering over the canopy of the trees, whipping up dust and leaves, as they dropped supplies or lifted men out. He fell silent, never once removing his searching gaze from the darkening path that led from the jungle to the edge of the swamp. Then he said, ‘They were piss-poor for resups and lift-offs – that’s true enough. But the DC3s were OK.’

Red sighed loudly, as if short of breath. ‘That’s my whole point. This was supposed to be an important exercise, preparing us for ’Nam, and yet we didn’t even get RAAF support. Those bastards in Canberra are playing silly buggers and wasting our time.’

‘No,’ Shagger replied firmly. ‘We didn’t waste our time. They might have fucked up, but we’ve learnt an awful lot in these five days and I think it’ll stand us in good stead once we go in-country.’

‘Let’s hope so, Sarge.’

‘Anyway, it’s no good farting against thunder, so you might as well forget it. If we pull off this ambush we’ll have won, then it’s spine-bashing time. We can…’

Suddenly Shagger raised his right hand to silence Red. At first he thought he was mistaken, but then, when he listened more intently, he heard what he assumed was the distant snapping of twigs and large, hardened leaves as a body of men advanced along the jungle path, heading for the swamp.

Using a hand signal, Shagger indicated to Red that he should adapt the firing position. When Red had done so, Shagger signalled that they should aim their fire in opposite directions, forming a triangular arc that would put a line of bullets through the front and rear of the file of enemy troops when it extended into the swamp from its muddy edge at the end of the path.

As they lay there waiting, squinting along their rifle sights, their biggest problems were ignoring the sweat that dripped from their foreheads into their eyes, and the insects that whined and buzzed about them, driven into a feeding frenzy by the smell of the sweat. In short, the most difficult thing was remaining dead still to ensure that they were not detected by their quarry.

Luckily, just as both of them were thinking that they might be driven mad by the insects, the first of the enemy appeared around the bend in the darkening path. They were marching in the classic single-file formation, with one man out ahead on ‘point’ as the lead scout, covering an arc of fire immediately in front of the patrol, and the others strung out behind him, covering arcs to the left and right.

When all the members of the patrol had come into view around the bed in the path, with ‘Tail-end Charlie’ well behind the others, covering an arc of fire to the rear, Shagger counted a total of eight men: two four-man patrols combined. All of them were wearing olive-green, long-sleeved cotton shirts; matching trousers with a drawcord waist; soft jungle hats with a sweat-band around the forehead; and rubber-soled canvas boots. Like Shagger and Red, they were armed with 7.62mm L1A1 SLRs and had 9mm Browning High Power pistols and machetes strung from their waist belts.

In short, the ‘enemy’ was a patrol of Australian troops.

‘Got the buggers!’ Shagger whispered, then aimed at the head of the single file as Red was taking aim at its rear. When the last man had stepped into the water, Shagger and Red both opened fire with their SLRs.

Having switched to automatic they stitched lines of spurting water across the front and rear of the patrol. Shocked, but quickly realizing that they were boxed in, the men under attack bawled panicky, conflicting instructions at one another, then split into two groups. These started heading off in opposite directions: one directly towards the islet, the other away from it.

Instantly, Shagger and Red jumped up to lob American M26 hand-grenades, one out in front of the men wading away from the islet, the other in front of the men wading towards it. Both grenades exploded with a muffled roar that threw up spiralling columns of water and rotting vegetation which then rained back down on the fleeing soldiers. Turning back towards one another, the two groups hesitated, then tried to head back to the jungle. They had only managed a few steps when Shagger and Red riddled the shore with the awesome automatic fire of their combined SLRs, tearing the foliage to shreds and showering the fleeing troops with flying branches and dangerously sharp palm leaves.

When the ‘enemy’ bunched up again, hesitating, Shagger and Bannerman stopped firing.

‘Drop your weapons and put your hands in the air!’ Shagger bawled at them. ‘We’ll take that as surrender.’

The men in the water were silent for some time, glancing indecisively at one another; but eventually a sergeant, obviously the platoon leader, cried out: ‘Bloody hell!’ Then he dropped his SLR into the water and raised both hands. ‘Got us fair and square,’ he said to the rest of his men. ‘We’re all prisoners of war. So drop your weapons and put up your hands, you happy wankers. We’ve lost. Those bastards have won.’

‘Too right, we have,’ Shagger and Red said simultaneously, with big, cheesy grins.

They had other reasons for smiling. This was the final action in the month-long training exercise ‘Traiim Nau’, conducted by Australian troops in the jungles and swamps of New Guinea in the spring of 1966.

In June that year, after they had returned to their headquarters in Swanbourne, and enjoyed two weeks’ leave, the men of 3 Squadron SAS embarked by boat and plane from Perth to help set up a Forward Operating Base (FOB) in Phuoc Tuy province, Vietnam.

2 (#u4d4a014a-9c1c-5d1a-98ac-07c92de41476)

In a small, relatively barren room in ‘the Kremlin’, the Operations Planning and Intelligence section, at Bradbury Lines, Hereford, the Commanding Officer of D Squadron, SAS, Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick ‘Paddy’ Callaghan, was conducting a most unusual briefing – unusual because there were only two other men present: Sergeants Jimmy ‘Jimbo’ Ashman and Richard ‘Dead-eye Dick’ Parker.

Ashman was an old hand who had served with the Regiment since it was formed in North Africa in 1941, fought with it as recently as 1964, in Aden, and now, in his mid-forties, was being given his next-to-last active role before being transferred to the Training Wing as a member of the Directing Staff. Parker had previously fought with the SAS in Malaya and Borneo and alongside Ashman in Aden. Jimbo was one of the most experienced and popular men in the Regiment, while Dead-eye, as he was usually known, was one of the most admired and feared. By his own choice, he had very few friends.

Lieutenant-Colonel Callaghan knew them both well, particularly Jimbo, with whom he went back as far as 1941 when they had both taken part in the Regiment’s first forays against the Germans with the Long Range Desert Group. Under normal circumstances officers could remain with the Regiment for no more than three years at a time. However, they could return for a similar period after a break, and Callaghan, who was devoted to the SAS, had been tenacious in doing just that. For this reason, he had an illustrious reputation based on unparalleled experience with the Regiment. At the end of the war, when the SAS was disbanded, Callaghan had returned to his original regiment, 3 Commando. But when he heard that the SAS was being reformed to deal with the Emergency in Malaya, he applied immediately and was accepted, and soon found himself involved in intense jungle warfare.

After Malaya, Callaghan was returned to Bradbury Lines, then still located at Merebrook Camp, Malvern, where he had worked with his former Malayan Squadron Commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Pryce-Jones, on the structuring of the rigorous new Selection and Training Programme for the Regiment, based mostly on ideas devised and thoroughly tested in Malaya. Promoted to the rank of major in 1962, shortly after the SAS had transferred to Bradbury Lines, Callaghan was returned once again to his original unit, 3 Commando, but then wangled his way back into the SAS, where he had been offered the leadership of D Squadron just before its assignment to the Borneo campaign in 1964.

Shortly after the successful completion of that campaign, when he had returned with the rest of the squadron to Bradbury Lines, he was returned yet again to 3 Commando, promoted once more, then informed that he was now too old for active service and was therefore being assigned a desk job in ‘the Kremlin’. Realizing that the time had come to accept the inevitable, he had settled into his new position and was, as ever, working conscientiously when, to his surprise, he was offered the chance to transfer back to the SAS for what the Officer Commanding had emphasized would be his ‘absolutely final three-year stint’. Unable to resist the call, Callaghan had turned up at Bradbury Lines to learn that he was being sent to Vietnam.

‘This is not a combatant role,’ the OC informed him, trying to keep a straight face. ‘You’ll be there purely in an advisory capacity and – may I make it clear from the outset – in an unofficial capacity. Is that understood?’

‘Absolutely, sir.’

Though Callaghan was now officially too old to take part in combat, he had no intention of avoiding it should the opportunity to leap in present itself. Also, he knew – and knew that his OC knew it as well – that if he was in Vietnam unofficially, his presence there would be denied and any actions undertaken by him likewise denied. Callaghan was happy.

‘This is top-secret,’ Callaghan now told Jimbo and Dead-eye from his hard wooden chair in front of a blackboard covered by a black cloth. ‘We three – and we three alone – are off to advise the Aussie SAS in Phuoc Tuy province, Vietnam.’

Jimbo gave a low whistle, but otherwise kept his thoughts to himself for now.

‘Where exactly is Phuoc Tuy?’ Dead-eye asked.

‘South-east of Saigon,’ Callaghan informed him. ‘A swampy hell of jungle and paddy-fields. The VC main forces units have a series of bases in the jungle and the political cadres have control of the villages. Where they don’t have that kind of control, they ruthlessly eliminate those communities. The Aussies’ job is to stop them.’

‘I didn’t even know the Aussies were there,’ Jimbo said, voicing a common misconception.

‘Oh, they’re there, all right – and have been, in various guises, for some time. In the beginning, back in 1962, when they were known as the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam – ‘the Team’ for short – they were there solely to train South Vietnamese units in jungle warfare, village security and related activities such as engineering and signals. Unlike the Yanks, they weren’t even allowed to accompany the locals in action against the North Vietnamese, let alone engage in combat.

‘Also, the Aussies and Americans reacted to the war in different ways. The Yanks were training the South Vietnamese to combat a massed invasion by North Vietnam across the Demilitarized Zone, established in 1954 under the Geneva Accords, which temporarily divided North Vietnam from South Vietnam along the 17th Parallel. The Americans stressed the rapid development of large forces and the concentration of artillery and air power to deliver a massive volume of fire over a wide area. The Aussies, on the other hand, having perfected small-scale, counter-insurgency tactics, had more faith in those and continued to use them in Vietnam, concentrating on map reading and navigation, marksmanship, stealth, constant patrolling, tracking the enemy and, of course, patience. Much of this they learnt from us back in Malaya during the fifties.’

‘That’s why they’re bloody good,’ Jimbo said.

‘Don’t let them hear you say that,’ Dead-eye told him, offering one of his rare, bleak smiles. ‘They might not be amused.’

‘If they learnt from us, sir, they’re good and that’s all there is to it.’

‘Let me give you some useful background,’ Callaghan said. ‘Back in 1962, before heading off to Vietnam, the Aussie SAS followed a crash training programme. First, there was a two-week briefing on the war at the Intelligence Centre in Sydney. Then the unit spent five days undergoing intensive jungle-warfare training in Queensland. In early August of that year, with their training completed, twenty-nine SAS men took a regular commercial flight from Singapore to Saigon, all wearing civilian clothing. They changed into the jungle-green combat uniform of the Australian soldier during the flight.’

‘In other words, they went secretly,’ Dead-eye said.

‘Correct. On arrival at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airport, they were split up into two separate teams. A unit of ten men was sent to Vietnamese National Training Centre at Dong Da, just south of Hue, the old imperial capital. That camp was responsible for the training of recruits for the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, the ARVN, but the base was also used as a battalion training centre and could accommodate about a thousand men. There, though constantly handicapped by the almost total corruption of the ARVN officers, they managed to train recruits and replacements for the regular ARVN Ranger units.

‘The second unit, consisting of a group of ten, was sent to the Civil Guard Training Centre at Hiep Kanh, north-west of Hue. The function of the Civil Guard was to protect key points in the provinces – bridges, telephone exchanges, radio stations and various government buildings. Though they weren’t nearly as corrupt and undisciplined as the troops of the ARVN, they were considered to be the poor relations, given clapped-out weapons and minimal supplies, then thrown repeatedly against the VC – invariably receiving a severe beating.

‘However, shortly after the arrival of the Aussie SAS, most of the Yanks were withdrawn and the Aussies undertook the training of the Vietnamese – a job they carried out very well, it must be said. But as the general military situation in South Vietnam continued to deteriorate, VC pressure on the districts around Hiep Kanh began to increase and in November ’63 the camp was closed and the remaining four Aussie advisers were transferred into the US Special Forces – the Ranger Training Centre at Due My, to be precise – some thirty miles inland from Nha Trang.’

‘They went there for further training?’ Jimbo asked.

‘Yes. I’m telling you all this to let you know just how good these guys are. At the Ranger Training Centre there were four training camps: the Base Camp and three specialized facilities – the Swamp Camp, the Mountain Camp and the Jungle Camp – for training in the techniques of fighting in those terrains. Reportedly, however, the men found this experience increasingly frustrating – mainly because they knew that a guerrilla war was being fought all around them, but they still weren’t allowed to take part in it.’

‘That would drive me barmy,’ Jimbo said. ‘It’s the worst bind of all.’

Dead-eye nodded his agreement.

‘Other team members,’ Callaghan continued, ‘were posted to Da Nang to join the CIA’s Combined Studies Division, which was engaged in training village militia, border forces and trail-watchers. Two of those Aussie SAS officers had the unenviable task of teaching Vietnamese peasants the techniques of village defence – weapon training, ambushing and booby-traps, and moat and palisade construction. The peasants were transported from their own villages, equipped and trained at Hoa Cam, on the outskirts of Da Nang, then sent back to defend their own homes. Unfortunately, this failed to work and, indeed, inadvertently fed weapons and supplies to the enemy. By this I mean that once they heard what was going on, the VC, who vastly outnumbered the South Vietnamese villagers, simply marched in, took over the villages, and seized the American arms and supplies for use against US and South Vietnamese forces.’

‘A bloody farce,’ Jimbo said.

‘And frustrating too. If the Aussies weren’t being driven mad by the corruption and incompetence of the ARVN officers, they were getting screwed by the South Vietnamese government, which bent according to the way the wind blew. For instance, one of the best men the Aussies had out there was Captain Barry Petersen, a veteran of the Malayan counter-insurgency campaigns. He was assigned to supervise paramilitary action teams of Montagnards in Darlac province in the Central Highlands…’

‘Montagnards?’ Dead-eye interrupted.

‘Yes. Darker than the Vietnamese, the Montagnards are nomadic tribesmen who distrust their fellow South Vietnamese. But they were won over by the CIA, who directed a programme to help them defend themselves against the commies. When Petersen arrived, he was put to work with a couple of the Montagnard tribes, quickly learnt the language and eventually forged a close relationship with them. This enabled him to teach them a lot, including, apart from the standard forms of village defence, the disruption of enemy infiltration and supply routes, the destruction of enemy food crops, and various forms of raiding, ambushing and patrolling. With the subsequent help of Warrant Officer Bevan Stokes, the Montagnards were given training in weapons, demolitions, map reading and radio communications. The results were impressive, but…’

‘Here it comes!’ Jimbo put in sardonically.

‘Indeed, it does…Petersen’s work with the Montagnards gained him the honour of a tribal chieftainship, success against the VC and recognition from his superiors. But the South Vietnamese government, alarmed that in two years Petersen had developed a highly skilled Montagnard army of over a thousand men who could be turned against them in a bid for independence, brought pressure to bear, forcing him to leave the country.’

‘So it’s tread with care,’ Dead-eye said.

Callaghan nodded. ‘Yes.’

‘Are the Aussies now on aggressive patrolling?’ Jimbo asked.

‘Yes. The watershed was in ’63 and ’64, when the South Vietnamese government changed hands no less than six times in eighteen months and the country descended into political chaos. Seeing what was happening, the Yanks stepped in again to rescue the situation and asked Australia for more advisers, some of whom were to operate with regular ARVN field units. This was the springboard to lifting the ban on combat. In July ’64 the Australian Army Training Team was strengthened to eighty-three men and the new recruits were assigned to the 1st ARVN Division in 1 Corps. Others were posted to military commands at province and district level, where their duties included accompanying Regional Force troops on operations, taking care of hamlet security, and liaising with ARVN troops operating in their area through the US advisory teams attached to the ARVN units. Officially, this was operations advising – the first step to actual combat.’

‘And now they’re in combat.’

‘Yes. The original members of the Team were soon followed by the 1st Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment – nearly eight hundred men, supported by an armoured personnel carrier troop, a signals detachment and a logistics support company. Those men were established in Vietnam by June 1965, under the operational control of the US 173rd Airborne Brigade at its HQ in Bien Hoa, north-east of Saigon, south of the Dong Nai river and the notorious VC base area known as War Zone D. Side by side with the Americans, they’ve been fighting the VC in that area for the past year and mopping them up. They’ve done a good job.’

‘But we’re not going there. We’re going to Phuoc Tuy province,’ said Dead-eye.

‘Correct. Even as we talk, the first Australian conscripts are arriving there as part of the new Australian Task Force. They’re based at Nui Dat and their task is to clear the VC from their base area in the Long Hai hills, known as the Minh Dam secret zone. They’ll be supported by the Australian SAS and our task is to lend support to the latter.’

‘They won’t thank us for that,’ Jimbo observed. ‘Those Aussies are proud.’

‘Too true,’ Dead-eye said.

Callaghan tugged the cover from the blackboard behind him, raised the pointer in his hand and tapped it against the words ‘PHUOC TUY’, highlighed on the map with a yellow marking pen. ‘The Phuoc Tuy provincial border is some fifty miles south-east of Saigon. As you can see, the province is bounded by the South China Sea, the Rung Sat swamps – a formidable obstacle to any advance – and Long Kanh and Binh Tuy provinces. The population of slightly over 100,000 is concentrated in the south central area and in towns, villages and hamlets close to the provincial capital, Baria. That area is rich in paddy-fields and market gardens. But the rest of the province, about three-quarters of it, is mostly flat, jungle-covered country, except for three large groups of mountains: the May Tao group in the north-east, the Long Hai on the southern coast, and the Dinh to the west. All these mountainous areas are VC strongholds.’

‘Where’s the Task Force located?’ Dead-eye asked.

‘Around Nui Dat. A steep hill covered in jungle and rising nearly 200 feet above the surrounding terrain. The area’s big enough for an airfield and for the Task Force to move on if the new base comes under attack.’

‘Major problems?’ Dead-eye asked.

‘The VC village fortifications of Long Phuoc and Long Tan, south-east of the base, were destroyed in a joint American and Vietnamese operation just before the Aussies moved in. The villages were laid waste and their inhabitants resettled in others nearby. While this effectively removed the VC from those two villages, it created a great deal of bitterness among the pro-VC inhabitants who are now even more busily spreading anti-government propaganda and helping to strengthen the local VC infrastructure. Meanwhile the major VC force is operating out of a chain of base areas in the northern jungles of the province, most with extensive bunker and tunnel complexes. Altogether there are seven battalions of VC in the area and they can be reinforced at short notice. Against that, the province has only one ARVN battalion permanently based there, supplemented by several Regional Force companies and the so-called Popular Forces – the PF – which are local militia platoons raised to defend the villages as well as bridges, communications facilities and so forth. They’re poorly equipped, poorly trained, and repeatedly turned over by the VC’.

‘Sounds wonderful,’ Jimbo murmured.

‘A real fairy tale,’ Callaghan replied, then shrugged and continued: ‘Right now the VC have the upper hand, both militarily and psychologically. They’ve isolated Xuyen Mock in the east and Due Than in the north, both of which contained South Vietnamese district headquarters. They’ve heavily infiltrated all the other districts. They regularly cut all roads in the province and tax the loyal villagers who try to get out. Nevertheless, the area’s of vital strategic importance to the US build-up, with Vung Tau earmarked to become a major port, supplying the delta, Saigon and Bien Hoa. This means that Route 15 on the western edge of Phuoc Tuy has to be kept clear as a prospective military supply route from Vung Tau to Saigon. In order to do this, the Task Force has to push the VC out of the central region of the province and provide a protective umbrella for the population there. The first step in this task is the clearing of the VC from the Nui Dat base area. This job will be given to the American 173rd Brigade, aided by the Australian 5th Battalion, which is being flown in right now. The latter will be supported by the Australian SAS and we’re there to advise them.’

‘Does our advisory role stretch to aggressive patrolling, boss?’ Dead-eye asked slyly.

Callaghan grinned. ‘Officially, we’re not supposed to be there at all – officially, we don’t exist – so once there, I suppose we just play it by ear and do what we have to do.’

‘But if we fuck up, we get no support,’ Jimbo said.

‘Correct.’

‘When do we fly out?’

‘Tomorrow. On a normal commercial flight, wearing civilian clothing. We change into uniform when we get there.’

‘Very good,’ Dead-eye said.

Callaghan handed each of the two men a closed folder.

‘These are your travel documents and bits and pieces of useful information. Report back here at six tomorrow morning. Before then, I’ll expect you to have digested everything in these folders. Finally, may I remind you once more that our presence there might cause resentment from the Aussie troops. In other words, you may find that the hearts and minds you’re trying to win aren’t those of the South Vietnamese peasants, but those of the Aussie SAS. They’re notoriously proud, so tread carefully. If there are no questions I’ll bid you good evening, gentlemen.’

Dead-eye and Jimbo stood up and left the briefing room, carrying their top-secret folders. When they had gone, Callaghan turned to the map behind him and studied it thoughtfully. Eventually, nodding to himself, he unpinned and folded it, then went to prepare for his flight the next day.

3 (#u4d4a014a-9c1c-5d1a-98ac-07c92de41476)

Though it was still early in the morning, the sun was up and the light was brilliant, with the Long Hai hills clearly visible from the deck of the carrier HMAS Sydney, where the troops were waiting for the landing-craft. Most were National Servicemen, young and inexperienced, their suntans gained from three months of recruit training in the Australian heat. As the 5th Battalion advance party, they had come alone, with only a sprinkling of Australian SAS NCOs in their midst, but they would be joined by the remainder of their battalion in a few days, then by 6th Battalion, with whom they would form the 1st Australian Task Force in Vietnam. Right now, apart from being weary after the tedious twelve-day voyage from Australia, they were tense with expectation, wondering if they could manage to get to shore without either hurting themselves getting in and out of the landing-craft or, even worse, being shot at by the enemy.

‘Minh Dam secret zone,’ Shagger said to Red as they stood together at the railing of the carrier. ‘And there,’ he continued, pointing north-west to the jungle-covered hills beyond the peninsula of Vung Tau, ‘is the Rung Sat swamps. They’re as bad as those swamps in Malaya, so let’s hope we avoid them. We can do without that shit.’

Grinning, Red adjusted his soft cap and studied the conscript troops as they scrambled from the deck into the landing-craft, to be lowered to the sea. Hardly more than schoolboys, they were wearing jungle greens, rubber-soled canvas boots and soft jungle hats. Getting into the landing-craft was neither easy nor safe, as they had to scramble across from gates in the railing, then over the steel sides of the dangling boats. This necessitated a hair-raising few seconds in mid-air, high above the sea, while laden with a tightly packed bergen and personal weapons. These included the 7.62mm L1A1 SLR, the 5.56mm M16A1 automatic rifle with the 40mm M203 grenade launcher, the 9mm L9A1 Browning semi-automatic pistol and, for those unlucky few, the 7.62mm M60 GPMG with either a steel bipod or the even heavier tripod. Also, their webbing bulged with spare ammunition and M26 high-explosive hand-grenades. Thus burdened, they moved awkwardly and in most cases nervously from the swaying deck of the ship to the landing-craft dangling high above the water in the morning’s fierce heat and dazzling light.

‘Shitting their pants, most of them,’ Red said as he watched the conscripts clambering into the vessel.

‘It’ll be diarrhoea as thin as water,’ Shagger replied, leaning against the railing and spitting over the side, ‘if the VC guns open up from those hills. They’ll smell the stench back in Sydney.’

‘I don’t doubt it at all, Sarge. Still, I’m sure they’ll do good when the time comes to kick ass for the Yanks. All the way with LBJ, eh?’

‘I wouldn’t trust LBJ with my grandmother’s corpse,’ Shagger replied. ‘But if our PM says it’s all the way with him, then that’s where we’ll go – once we get off this ship, that is.’

Shagger and Red were the only two Australian SAS men aboard HMAS Sydney, present to take charge of the stores and vehicles of 3 Squadron, which were being brought in on this ship. The rest of the squadron was to be flown in on one plane directly from the SAS base at Campbell Barracks, Swanbourne, once they’d completed their special training in New Guinea in a few days’ time. Meanwhile Shagger had been placed temporarily in charge of this troop of regular army conscripts and was responsible for getting them from ship to shore. Once there, he and Red would split from them and go their own way.

‘Whoops! Here she comes!’

The landing-craft for Shagger’s men was released from the davits and lowered to deck level, where it hung in mid-air, bouncing lightly against the hull with a dull, monotonous drumming sound. When Red had opened the gate in the railing, Shagger slapped the first man on the shoulder and said, ‘Over you go, lad.’

The young trooper, eighteen at the most, glanced down the dizzying depths to the sea and gulped, but then, at a second slap on the shoulder, gripped his SLR more firmly in his left hand and, with his other, reached out to take hold of the rising, falling side of the landing-craft, and pulled himself over and into it. When he had done so, the other men, relieved to see that it was possible, likewise began dropping into the swaying, creaking vessel one after the other. When everyone was in, Shagger and Red followed suit.

‘Hold on to your weapons,’ the sergeant told the men packed tightly together. ‘This drop could be rough.’

And it was. With the chains screeching against the davits, the landing-craft was lowered in a series of swooping drops and sudden stops, jerking back up a little and swinging from side to side. The drop did not take long, though to some of the men it seemed like an eternity and they were immensely relieved when, with a deafening roaring, pounding sound, the boat plunged into the sea, drenching them in the waves that poured in over the sides. The engine roared into life, water boiled up behind it, and it moved away from the towering side of the ship, heading for shore.

‘Fix bayonets!’ Shagger bawled above the combined roar of the many landing-craft now in the water.

As the bayonets were clicked into place, Shagger and Red grinned at each other, fully aware that as the VC guns had not already fired, they would not be firing; and that the men would be disembarking on to the concrete loading ramp in the middle of the busy Vung Tau port area rather than into a murderous hail of VC gunfire. In fact, the reason for making the men fix bayonets was not the possibility of attack as the landing-craft went in, but to instil in them the need to take thorough precautions in all circumstances from this point on. Nevertheless, when, a few minutes later, the landing-craft had ground to a halt, the ramp was lowered, and the men marched out on to the concrete loading ramp with fixed bayonets, the American and Vietnamese dock workers burst into mocking applause and wolf whistles.

‘Eyes straight ahead!’ Shagger bawled. ‘Keep marching, men!’

Marching up ahead, Shagger and Red led the conscript troops to the reception area of the Task Force base, which had been set up on a deserted stretch of beach on the eastern side of the Vung Tau peninsula. The Task Force consisted of two battalions with supporting arms and logistic backup, a headquarters staff, an armoured personnel carrier squadron, an artillery regiment, an SAS squadron, plus signals, engineer and supply units, totalling 4500 men – so it was scattered across a broad expanse of beach.

‘Sergeant Bannerman reporting, sir,’ Shagger said to the 1st Australian Logistic Support Group (1 ALSG) warrant officer in charge of new arrivals. ‘Three Squadron SAS. In temporary charge of this bunch of turnip-heads and now glad to get rid of them.’

‘They all look seasick,’ the warrant officer observed.

‘That and a touch of nerves. They’re National Servicemen, after all.’

‘Not tough bastards like the SAS, right?’

‘You said it.’

‘Now piss off back to your SAS mates, Sarge, and let me deal with this lot. I’ll soon knock them into shape.’

‘Good on you, sir. Now where would the supplies for 3 Squadron be?’

‘I’m regular army, not SAS. I look after my own. You’ve only been here five minutes and you’re confessing that you’ve already lost your supplies? With friends like you, who needs enemies?’

‘Thanks for that vote of confidence, sir. I think I’ll be on my way.’

‘As long as you’re not in my way, Sarge. Now take to the hills.’

‘Yes, sir!’ Shagger snapped, then hurried away, grinning at Red, to look for his missing supplies. In the event, they had to be separated from the general mess of what appeared to be the whole ship’s cargo, which had been thrown haphazardly on to the beach, with stores scattered carelessly among the many vehicles bogged down in the sand dunes. Luckily Shagger found that the quartermaster for 1 ALSG was his old mate Sergeant Rick McCoy, and with his help the supplies were gradually piled up near the landing zone for the helicopters.

‘A nice little area,’ McCoy informed Shagger and Red, waving his hand to indicate the sweeping beach, now covered with armoured cars, half-tracks, tents, piles of canvas-covered wooden crates and a great number of men, many stripped to the waist as they dug trenches, raised pup tents or marched in snaking lines through the dunes, heading for the jungle-covered hills beyond the beach. ‘Between these beaches and the mangrove swamps to the west you have Cap St Jacques and the port and resort city of Vung Tau. Though Vung Tau isn’t actually part of Phuoc Tuy province, it’s where we all go for rest and convalescence. Apparently the VC also use the town for R and C, so we’ll all be nice and cosy there.’

‘You’re kidding!’

‘No, I’m not. That place is never attacked by Charlie, so I think he uses it. How the hell would we know? One Vietnamese getting drunk or picking up a whore looks just like any other; so the place is probably filled with the VC. That thought should lend a little excitement to your next night of bliss.’

‘Bloody hell!’ said Red.

In fact, neither Red nor Shagger was given the opportunity to explore the dangerous delights of Vung Tau as they were moved out the following morning to take part in the establishment of an FOB, a forward operating base, some sixteen miles inland at Nui Dat. Lifted off in the grey light of dawn by an RAAF Caribou helicopter, they were flown over jungle wreathed in mist and crisscrossed with streams and rivers, then eventually set down on the flat ground of rubber plantations surrounding Nui Dat, a small but steep-sided hill just outside Baria.

The FOB was being constructed in the middle of the worst monsoon the country had experienced for years. Draped in ponchos, the men worked in relentless, torrential rain that had turned the ground into a mud-bath and filled their shelters and weapons pits with water. Not only did they work in that water – they slept and ate in it too.

To make matters worse, they were in an area still dominated by the enemy. Frequently, therefore, as they toiled in the pounding rain with thunder roaring in their ears and lightning flashing overhead, they were fired upon by VC snipers concealed in the paddy-fields or behind the trees of the rubber plantations. Though many Aussies were wounded or killed, the others kept working.

‘This is bloody insane,’ Shagger growled as he tried to scoop water out of his shallow scrape and found himself being covered in more mud. ‘The floods of fucking Noah. I’ve heard that in other parts of the camp the water’s so deep the fellas can only find their scrapes when they fall into them. Some place to fight a war!’

‘I don’t mind,’ Red said. ‘A bit of a change from bone-dry Aussie. A new experience, kind of. I mean, anything’s better than being at home with the missus and kids. I feel as free as a bird out here.’

‘We’re belly down in the fucking mud,’ Shagger said, ‘and you feel as free as a bird! You’re as mad as a hatter.’

‘That some kind of bird, is it, Sarge?’

‘Go stuff yourself!’ said Shagger, returning to the thankless task of bailing out his scrape.

Amazingly, even in this hell, the camp was rapidly taking shape. Styled after a jungle FOB of the kind used in Malaya, it was roughly circular in shape with defensive trenches in the middle and sentry positions and hedgehogs: fortified sangars for twenty-five-pound guns and a nest of 7.62mm GPMGs. This circular base was surrounded by a perimeter of barbed wire and claymore mines. Shagger and Red knew the mines were in place because at least once a day one of them would explode, tripped by the VC probing the perimeter defences with reconnaissance patrols. Still the Aussies kept working.

‘Now I know why the Yanks fucked off,’ Shagger told Red as they huddled up in their ponchos, feet and backside in the water, trying vainly to smoke cigarettes as the rain drenched them. ‘They couldn’t stand this bloody place. Two minutes of rain, a single sniper shot, and those bastards would take to the hills, looking for all the comforts of home and a fortified concrete bunker to hide in. A bunch of soft twats, those Yanks are.’

‘They have their virtues,’ Red replied. ‘They just appreciate the good things in life and know how to provide them. I mean, you take our camps: they’re pretty basic, right? But their camps have air-conditioners, jukeboxes and even honky-tonk bars complete with Vietnamese waiters. Those bastards are organized, all right.’

‘We’ve got jukeboxes,’ Shagger reminded him.

‘We had to buy them off the Yanks.’

‘Those bastards make money out of everything.’

‘I wish I could’, Red said.

‘Well, we’re not doing so badly,’ said Shagger. ‘This camp’s coming on well.’

It was true. Already, the initial foxholes and pup tents had been replaced by an assortment of larger tents and timber huts with corrugated-iron roofs. Determined to enjoy themselves as best they could, even in the midst of this squalor, the Aussies, once having raised huts and tents for headquarters, administration, communications, first aid, accommodation, ablutions, transport, supplies, weapons and fuel, then turned others into bars, some of which boasted the jukeboxes they’d bought from the Yanks. There were also four helicopter landing zones and a single parking area for trucks, jeeps, armoured cars and tanks.

While they were waiting for the other members of 3 Squadron to arrive, Shagger and Red between them supervised the raising of a large tent to house the SAS supplies already there. The tent was erected in one day with the help of Vietnamese labourers stripped to the waist and soaked by the constant rain. When it was securely pegged down, the two SAS men used the same labourers to move in the supplies: PRC 64 and A510 radio sets, PRC 47 high-frequency radio transceivers, batteries, dehydrated ration packs, US-pattern jungle boots, mosquito nets and a variety of weapons, including SLRs, F1 Carbines and 7.62mm Armalite assault rifles with twenty-round box magazines. Shagger then inveigled 1 ALSG’s warrant-officer into giving him a regular rotation of conscript guards to look after what was, in effect, 3 Squadron’s SAS’s quartermaster’s store.

‘I thought you bastards were supposed to be self-sufficient,’ the warrant officer said.

‘Bloody right,’ Shagger replied.

‘So how come you can’t send enough men in advance to look after your own kit?’

‘They’re still mopping up in Borneo,’ Shagger said, ‘so they couldn’t fly straight here.’

‘And my name’s Ned Kelly,’ the warrant officer replied, then rolled his eyes and sighed. ‘OK, you can have the guards.’

‘I’ve got that prick in my pocket,’ Shagger told Red when they were out of earshot of the warrant officer.

‘You’ll have him up your backside,’ Red replied, ‘if you ask for anything else.’

When construction of the camp had been completed, five days after Shagger and Red had arrived, the two men were called to a briefing in the large HQ tent. By this time the rest of 3 Squadron had arrived by plane from Perth and were crowding out the tent, which was humid after recent rain and filled with whining, buzzing flies and mosquitoes. As the men swotted the insects away, wiped sweat from their faces, and muttered a wide variety of oaths, 1 ALSG’s CO filled them in on the details of the forthcoming campaign against the Viet Cong.

‘The first step,’ he said, ‘is to dominate an area surrounding the base out to 4000 yards, putting the base beyond enemy mortar range. We will do this with aggressive patrolling. The new perimeter will be designated Line Alpha. The second step is to secure the area out to the field artillery range – a distance of about 11,000 yards. Part of this process…’ – he paused uncomfortably before continuing – ‘is the resettlement of Vietnamese living within the area.’

‘You mean we torch or blow up their villages and then shift them elsewhere?’ Shagger said with his customary bluntness.

The CO sighed. ‘That, Sergeant, is substantially correct. I appreciate that some of you may find this kind of work rather tasteless. Unfortunately it can’t be avoided.’

‘Why? It seems unnecessarily brutal – and not exactly designed to win hearts and minds.’

The CO smiled bleakly, not being fond of the SAS’s reputation for straight talking and the so-called ‘Chinese parliament’, an informal talk between officers, NCOs and other ranks in which all opinions were given equal consideration. ‘The advantage of resettling the villagers is that whereas the VC aren’t averse to using villagers as human shields, we can, in the event of an attack, deploy our considerable fire-power without endangering them – another way of winning their hearts and minds.’

‘Good thinking,’ Shagger admitted.

‘I’m pleased that you’re pleased,’ the CO said, wishing the outspoken SAS sergeant would sink into the muddy earth and disappear, but unable to show his disapproval for fear that his own men would think him a fool. ‘So one of our first tasks will be to finish the destruction of a previously fortified village located approximately a mile and a quarter south-east of this base. Huts and other buildings will be torched or blown up and crops destroyed. This we will do over a period of days. Unpleasant though this may seem to you, it’s part of the vitally necessary process of reopening the province’s north-south military supply route, and eventually driving the enemy back until they’re isolated in their jungle bases.’

‘So what’s the SAS’s role in all this?’ Shagger asked him.

‘Your task is to pass on the skills you picked up in Borneo to the ARVN troops and to engage in jungle bashing – patrolling after the VC who’ve turned this camp into their private firing range. Eventually, when Line Alpha has been pushed back to beyond the limits of field artillery, you’ll be given the task of clearing out a VC stronghold in a bunker-and-tunnel complex. The location will be given to you when the time comes.’

‘Why not give us the location now?’ Red asked.

‘Because the less you know the better,’ the CO replied.

‘You mean if we’re captured by Charlie, we’ll be tortured for information,’ Red replied.

‘Yes. And Charlie’s good at that. Now, there’s another important aspect to this operation. You’ll be advised and assisted – though I should stress that the collaboration should be mutually beneficial – by a three-man team from Britain’s 22 SAS. They’ll be arriving from the old country in four days’ time.’

A murmur of resentment filled the room and was only ended when Shagger asked bluntly: ‘Why do we need advice from a bunch of Pommie SAS? We know as much about this business as they do. We can do it alone.’

‘I’m inclined to agree, Sergeant, but the general feeling at HQ is that the British SAS, with their extensive experience in jungle warfare, counter-insurgency patrolling, and hearts-and-minds campaigning in places as different and as far apart as Malaya, Oman, Borneo and, more recently, Aden, have a distinct advantage when it comes to operations of this kind. So, whether you like it or not, those three men – a lieutenant-colonel and two sergeants – will soon be flying in to act as our advisers.’

‘Bloody hell!’ Red exclaimed in disgust.

The CO ignored the outburst. ‘Are there any questions?’ he asked.

As the men had none, the meeting broke up and they all hurried out of the humid tent, into the drying, steaming mud of the compound of the completed, now busy, FOB. The sky above the camp was filled with American Chinook helicopters and B52 bombers, all heading inland, towards the Long Hai hills.

4 (#u4d4a014a-9c1c-5d1a-98ac-07c92de41476)