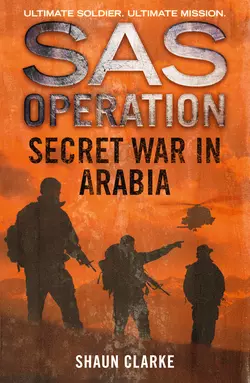

Secret War in Arabia

Shaun Clarke

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But will the SAS succeed in freeing Oman from the deadly grip of fanatical guerrillas?In the arid deserts and mountains of Arabia a ‘secret’ war is being fought.While Communist-backed Adoo guerrillas have been waging a campaign of terror against Oman, British Army Training Teams have been winning hearts and minds with medical aid and educational programmes. Now the time has come to rid the country of the guerrillas, not only to free Oman, but also to guarantee the safe passage of Arabian oil to the West.Only one group of men is capable of doing this job, and on the night of October 1, 1971, two squadrons of SAS troopers, backed by the Sultan’s Armed Forces and fierce, unpredictable Firqat Arab fighters, start to clear the fanatical Adoo from the sun-scorched summit of the mighty Jebel Dhofar. In doing so, the men of the SAS embark on one of their most daring and unforgettable adventures.

Secret War in Arabia

SHAUN CLARKE

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1993

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1993

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © MILpictures/Tom Weber/Getty Images (soldiers); Shutterstock.com (helicopter & textures)

Shaun Clarke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008154882

Ebook Edition © November 2015 ISBN: 9780008154899

Version: 2015-10-15

Contents

Cover (#ud6bd5d6e-043c-5663-b263-354f091b3ca3)

Title Page (#u33749927-19e4-599b-b813-c5faa30d68e5)

Copyright (#u20a16f32-77d1-5821-a20b-471a473a8ee9)

Prelude (#u1a0e1f8b-d7b9-5f81-8e34-4818ed81b870)

Chapter 1 (#u7d833a78-3d39-531d-b48e-a98fb99e487a)

Chapter 2 (#ub3ac11c1-c6fd-5ded-b982-9c7b750b4d7d)

Chapter 3 (#ubaa97913-da2f-56b8-a818-058fe85ce06c)

Chapter 4 (#ud4c290ba-3f73-5df9-a19d-517e8d5cae2b)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prelude (#uf4848077-50ad-5a78-8eb5-43828dc0e07b)

Framed by the veils of his Arab shemagh, the guerrilla’s face was good-humoured, even kindly. This made it all the more shocking when he expertly jabbed his thin-bladed knife through Sa’id’s eyelid and over the top of his eyeball, twisting it downward to slice through the optic nerve at the back of the retina and gouge the eye from its socket.

The old man’s pain was indescribable, exploding throughout his whole being, drawing from him a scream not recognizably human and making him shudder and strain frantically against his tight bonds. Glancing down through the film of tears in his remaining eye, he saw his own eyeball staring up at him from the small pool of blood in the guerrilla’s hand.

‘Will you now renounce your faith?’ the guerrilla asked. ‘What say you, old man?’

Racked with pain and disbelief, his heart racing too quickly, Sa’id glanced automatically across the clearing. He saw the troops of the Sultan’s Armed Forces lying on the ground, shot dead with pistols, soaked in blood. Directly above them, the bodies of other village elders were dangling lifeless from ropes.

Beyond the hanged men, clouds of smoke were still rising from the smouldering ashes of homes put to the torch. The sounds of wailing women, screaming girls and pleading men rose above sporadic outbursts of gunfire and hoarse, self-satisfied male laughter.

Life in this and the other villages of the country had become nightmarish in recent months, but today, in this particular village, all hell had broken loose.

First, at dawn, the Sultan’s troops had encircled the village to accuse the people of aiding the guerrillas and to prevent them doing so in the future. This they did by torching the whole settlement, cementing over the well without which the villagers could not survive, and hanging a few suspected communist sympathizers from ropes tied to poles hammered hastily into the ground. Then, in the late afternoon, the communist guerrillas had arrived to terrorize the already suffering Muslim villagers and, in particular, to pursue their merciless campaign of making the repected elders of each community renounce their faith.

‘So, old man,’ the guerrilla taunted Sa’id, still holding the bloody eyeball in his hand for him to see, ‘will you renounce your vile Muslim faith or do I gouge out the other one?’

Still in a state of shock, barely aware of his own actions, Sa’id nevertheless managed to croak, ‘No, I cannot do that. No matter what you do to me, I cannot renounce my faith.’

‘You’re a stubborn old goat,’ the guerrilla said. ‘Perhaps, if you don’t care for yourself, you’ll be more concerned for your daughters.’ Casually throwing Sa’id’s eyeball into the dirt, he turned to the armed guerrillas behind him. ‘Take the Muslim bitches,’ he said, ‘and make proper whores of them.’

‘No!’ Sa’id cried out in despair, as the men raced into the ruins of his half-burnt home and the screams of his virgin daughters rent the air. It went on a long time: the girls screaming, the guerrillas laughing, while Sa’id sobbed, strained against his bonds, tasted the blood still pouring from his eye socket, and mercifully slipped in and out of consciousness.

But he was still coherent when his three adolescent daughters, their clothes bloody and hanging in shreds from their bruised, deflowered bodies, were thrown out of the ruins of his mud-and-thatch hut to huddle together, sobbing shamefully, in the dust.

Even as the horrified Sa’id stared at them with his one remaining eye, the guerrilla with the good-humoured face turned to him and asked, ‘Now will you renounce your faith, old man?’

When Sa’id, too shocked to respond, simply stared blankly out of his good eye, the guerrilla snorted with disgust, gouged out his other eye, slashed through his bonds even as the old man was screaming, and stepped aside to let him fall to the ground.

Sa’id could hear his daughters wailing, even though he could not see them. Nor could he see the other raped and beaten women, the men dangling from ropes, the shot SAF troops, the burned ruins of the village huts and the life-giving well sealed with cement. All he saw was the darkness in which he would spend the rest of his days.

Sa’id wept tears of blood.

1 (#uf4848077-50ad-5a78-8eb5-43828dc0e07b)

‘Badged!’ Trooper Phil Ricketts said, proudly holding up his beige beret to re-examine the SAS winged-dagger badge stitched to it the previous day by his wife, Maggie. ‘I can hardly believe it.’

‘Believe it, you bleedin’ probationer,’ said Trooper ‘Gumboot’ Gillis, who was wearing his own brand-new badged beret. ‘You earned it, mate. We all did!’

‘I’m surprised I actually made it,’ said Andrew Winston, a huge black Barbadian, glancing around the crowded Paludrine Club and clearly proud to be allowed into it at last, ‘particularly as I almost gave up once or twice.’

‘We probably all thought about it,’ said Tom Purvis, ‘but that’s all we did. Otherwise we wouldn’t be drinking in here.’ He glanced around the noisy, smoky recreation room of 22 SAS Regiment. ‘We’re here because, although we may have thought about it, we didn’t actually give up.’

‘I thought about it once,’ Ricketts said. ‘I’ll have to admit that. Once – only once.’

He had done so during that final, awful night on the summit of Pen-y-fan. At other times during the 26 weeks of relentless physical and mental testing, he had wondered what he was doing there and if it was all worth it. But only that once had the thought of actually giving up crossed his mind – in the middle of that dark, stormy night in the Brecon Beacons, where, for one brief, despairing moment, he thought he had reached the end of his tether.

Even now, he could only look back on the rigours of Initial Selection, ‘Sickeners One and Two’, Continuation Training, Combat Training and, finally, the parachute course, with a feeling of disbelief that he had actually undergone it and lived to tell the tale. He had arrived at the SAS camp of Bradbury Lines, in the Hereford suburb of Redhill, in the full expectation that he was in for a rough time, but nothing had quite prepared him for just how rough it actually turned out to be.

‘What you are about to undergo,’ the Squadron Commander, Major Greenaway, had informed over a hundred recruits that first morning as they sat before him on rows of hard seats in the training wing theatre, or Blue Room, of Bradbury Lines, ‘is the most rigorous form of testing ever devised for healthy men. No matter how good you believe yourselves to be as soldiers – and if you didn’t think you were good, you wouldn’t be here now – you will find yourselves tested to the very limits of your endurance. Our selection process offers no mercy. You can fail at any point over the 26 weeks. Some will fail on the first day, some on the very last. If you are failed, you will find yourselves standing on Platform Four of Redhill Station, being RTU’d.’ A few of the listening men glanced at each other, but no one dared say a word. ‘There is no appeal,’ Greenaway continued. ‘Only a small number of you will manage to complete the course successfully – a very small number. Let that simple, brutal truth be your bible from this moment on.’

It was indeed a brutal truth, as Ricketts was to discover from the moment the briefing ended and the men were rushed from the Blue Room – passing under a sign reading ‘For many are called but few are chosen’ – to the Quartermaster’s stores to be kitted out with a bergen backpack, sleeping bag, webbed belts, a wet-weather poncho, water bottles, a heavy prismatic compass, a brew kit, three 24-hour ration packs and Ordnance Survey maps of the Brecon Beacons and Elan Valley, where the first three-day trial, known as Sickener One, would take place.

Once kitted out, they hurried from the QM’s stores to the armoury, where they were supplied with primitive Lee Enfield 303 rifles. Allocated their beds, or ‘bashas’, in the barracks of the training wing, they were allowed to drop their kit off in the ‘spider’ – an eight-legged dormitory area – and have a good lunch in the cookhouse. Immediately after that, the harsh selection process began.

‘Christ,’ Gumboot said, placing his pint glass on the table and licking his wet lips, ‘it seems a lot longer than it was. Only six months! It seems like six years.’

Ricketts remembered it only too well. The few days leading up to Sickener One were filled with rigorous weapons training and arduous runs, fully kitted, across the deceptively gentle hills of the Herefordshire countryside, each one longer and tougher than the one before, and all of them leading to a final slog up an ever-steeper gradient that tortured lungs and muscles.

The first of the crap-hats, or failures, were weeded out during those runs and humiliatingly RTU’d, or returned to their original unit. Those remaining, now fully aware of just how many failures there would be, instinctively drew into themselves, not wanting to become too friendly with those likely to soon suffer the same fate.

‘And to think,’ Tom Purvis said, shaking his head from side to side in wonder, ‘that at the time we thought nothing could be worse than Sickener One!’

‘It’s helpful not to know too much,’ Jock McGregor said.

‘It sure is, man,’ big Andrew added, flashing his perfect teeth. ‘If we’d known that Sickener One was just kids’ stuff compared to what was coming, we’d never have stuck it out for the rest.’

It was a greatly reduced number of SAS aspirants from various British Army regiments who had awakened in the early hours of a Saturday morning, showered, shaved, pulled on their olive-green uniforms, or OGs, picked up their rifles and dauntingly heavy bergens, then hurried out to the waiting four-ton Bedford trucks. After being driven north along the A470, they were eventually dropped off in the Elan Valley, in the Cambrian Mountains of mid-Wales. An area of murderously steep hills and towering ridges, it had been chosen for its difficult, dangerous terrain and harsh weather as the perfect testing ground for Sickener One. This gruelling three-day endurance test is based on hiking and climbing while humping a heavily packed bergen and weapons, then repeatedly ‘cross-graining the bukits’.

Derived from the Malay – Malaysia was where the exercise was first practised – this last expression means going from one summit or trig point to another by hiking up and down the steep, sometimes sheer hills rather than taking the easy route around them. It takes place in the most rugged terrain and the foulest weather imaginable, including fierce wind, rain or blinding fog. Each conquered summit is followed by another, and the slightest sign of reluctance on the part of the climber is met by a shower of abuse from a member of the directing staff (DS), or – a psychological killer – by the softly spoken suggestion that the candidate might find it more sensible to give up and return to the waiting Bedfords.

Those taking this advice seriously were instantly failed and placed on RTU, never to be given the chance to try again. This happened to many during the three days of Sickener One.

Those who survived the first day, even though exhausted and disorientated, then had to basha down at the most recent RV, or rendezvous, no matter how hostile the terrain. Invariably, when they did so, they were frozen and wet, often with swollen feet and shoulders blistered by the bergen. They were then forced to spend the night in the same appalling weather, eating 24-hour rations heated on portable hexamine stoves, drinking tea boiled on the same, before bedding down in sleeping bags protected from the elements only by waterproof ponchos.

Given the filthy, windy weather – for which that time of the year had been deliberately chosen – few of the men got much sleep and the next day, even wearier than before, they not only cross-grained more bukits, but were faced with the dreaded entrail ditch, filled with stagnant water and rotting sheep’s innards, standing in for the blood and bone of butchered humans. The candidates had to crawl through this vile mess on their bellies, face down, holding their rifles horizontally – it was known as the ‘leopard crawl’ – ignoring the stench, trying not to swallow any of the mess, though certainly swallowing their own bile when they brought it up. Failure to get through the entrail ditch was an RTU offence which further reduced the number of aspirants.

‘I fucking dreaded that,’ Tom said, lighting a cigarette and puffing smoke. ‘It was only the thought of Platform Four that kept me going when things got rough.’

‘Right,’ said Bill Raglan, who was born and bred in Pensett, in the West Midlands, and had little education but a lot of intelligence. Bill’s face was badly scarred from the many fights he had been in before the regular Army channelled his excess energy in a more positive direction. ‘Can you imagine the humiliation, standing there with the other rejects? Then having to go back to your old regiment with your tail between your legs. That kept me going all right!’

At dawn, after a second night of sleeping out in frozen, rainswept open country, numb from the cold and with their outfits still stinking from their encounter with the entrail ditch, they had been ordered to wade across a swollen, dangerously fast river, holding their rifles above their heads as the water reached their chests. One man refused to cross and was instantly failed; another was swept away, rescued and then likewise failed. While both men were escorted to the waiting Bedfords, the others, though still wet and exhausted from contending with the river, were forced to carry one of their DS supervisors, complete with his bergen and weapons, between them on a stretcher for what should have been the last mile of the hike. However, when told at the end of that most killing of final legs that the Bedfords had gone and they would have to hike the last ten miles – in short, that they had been conned – some of them lost their temper with their supervisors, while others simply sat down wearily and called it a day.

The latter were failed and placed on RTU. A few more were lost on that draining ten miles, leaving a greatly reduced, less optimistic group to go on to the torments of Sickener Two.

‘I mean, you can’t believe what those fuckers will dream up for you, can you?’ Jock asked rhetorically, really speaking to himself in a daze of disbelief as he thought back on all he had been through. ‘You get through Sickener One, thinking you’re Superman, then they promptly make you feel like a dog turd with Sickener Two. Those bastards sure have their talents!’

In fact, between the two exercises there had been more days of relentless grind in the shape of long runs, map-reading, survival and weapons training, and psychological testing. Then the dreaded first day of Sickener Two finally arrived, beginning with the horror of the Skirrid mountain, which rises 1640 feet above the gently rolling fields of Llanfihangel and is surmounted by a trig point ideal for map-reading. Naturally, for the SAS, the only way to the top was by foot, with the usual full complement of packed bergen, heavy webbing and weapons.

In addition, the route specially chosen by the DS for the exercise carefully avoided the gentler slopes and forced the candidates up the nearly vertical side. As part of the tests, each man had to take his turn at leading the others up the sheer face to the summit, using his Silvas compass, then guiding them back down without mistakes. This procedure was repeated many times throughout the long day, until each man had taken his turn as leader and all of them were suffering agonies of body and mind.

Some collapsed, some got lost through being dazed, and others simply dropped out in despair, while those remaining went on to week three. For this the teams were split up and each man was tested alone, with the runs becoming longer, the mountain routes steeper and the bergens packed more heavily every day until they became back-breaking loads. Added to this was an ever more relentless psychological onslaught, designed to test mental stamina, and including cruel psychological ploys such as last-minute changes of plan and awakenings at unexpected times of the day or night. On top of all this, even more brutal, unexpected physical endurance tests were introduced just as the men reached maximum exhaustion or disorientation.

The climax of this week of hell on earth was a repeated cross-graining of the peaks of the Pen-y-fan, at 2906 feet the highest mountain in the Brecon Beacons, one day after the other, each hike longer than the previous one, with extra weight being added to the bergens each time. On even the highest peak, the DS was liable to leap out of nowhere, and hurl a volley of questions at the exhausted, often dazed applicant, who, if he failed to supply an answer, would be sent back down in disgrace, bound for Platform Four.

By the fifth day of the third week, after a final, relentlessly punishing, 40 miles solo cross-graining of the bukits, known as the ‘Fan Dance’ – across icy rivers, peat bogs, pools of stagnant water and fields of fern; up sandstone paths and sheer ridges, in driving rain and blinding fog, carrying a 45lb bergen, as well as water bottles and heavy webbing – most of the candidates had been weeded out. In the end, under two dozen of the original hundred-odd men were deemed to have passed Initial Selection and allowed to go on to Continuation Training.

Phil Ricketts was one of them. He had had his moment of doubt on the summit of Pen-y-fan, when in a state of complete exhaustion, cold and hungry, whipped by the wind, feeling more alone than he had ever done before, he wanted to scream his protest and give up and go back down. But instead he endured and went on to do the rest of the nightmarish exercise and return to the RV by the selected route. He felt good when he finished and was applauded by his stern instructors.

Given a weekend break, Ricketts spent it with his wife in Wood Green, North London, where Maggie lived with her parents during his many absences from home. Even in the regular Army, he had never felt as fit as he was after Initial Selection, and he made love to Maggie, to whom he had only been married a year, with a passion that took her breath away. As they were to find out later, their first child, Anna, was conceived during that happy two days.

‘You remember that first weekend break we got?’ Ricketts asked his mates. ‘Immediately after passing Initial Selection? What did you guys do that weekend?’

‘I went back to Brixton,’ Andrew said, ‘to see my white Daddy and black Mammy, then screw my Scandinavian girlfriend. It was well worth the journey, believe me.

‘I banged a whore in King’s Cross,’ Jock said without emotion.

‘Bill and I shared a hired car and drove back to the Midlands,’ said Tom. ‘Though my folks come from Wolverhampton they’re now living in Smethwick, which isn’t too far from where Bill lives, in Pensett. So since neither of us were keen to spend too much time with our families, we drove between the two towns, having a pint here, another pint there, and gradually getting pissed as newts.’

‘I can hardly remember the drive back,’ Bill said with a broad grin, ‘so I like to think we only made it because of our SAS training. Who dares wins, and so on.’

‘And you, Gumboot?’ Ricketts asked. ‘Did you go and see your wife?’

‘No,’ Gumboot answered, puffing smoke and sipping his beer at the same time.

‘But you’d only been married six months,’ Ricketts said.

‘Six months too fucking long,’ Gumboot said. ‘Got her pregnant, didn’t I? Besides, we only had one weekend, which leaves no time to go all the way to Devon and back.’

‘You could have travelled on Friday night and come back on Sunday,’ Andrew pointed out.

‘OK, I’ll admit it,’ Gumboot said pugnaciously. ‘I didn’t want to spend my free weekend with a bloody bean bag, so I slipped into London. I’m amazed I didn’t run into Jock, since I had a few pints in King’s Cross on Saturday evening.’

‘I probably saw you and avoided you,’ Jock replied, ‘I can be fussy at times.’

‘Up yours, mate.’ Gumboot swallowed some more beer, wiped his lips, and grinned mischievously. ‘Ah, well, it was only a weekend – and over all too soon.’

On that, at least, they all agreed.

When they had returned to Hereford that Monday morning, some with blinding hangovers, others simply sleepless, they had been flung with merciless efficiency into their fourteen weeks of Continuation Training, learning all the skills required to be a member of the basic SAS operational unit: the four-man patrol. These skills included weapons handling, combat and survival, reconnaissance, signals, demolitions, camouflage and concealment, resistance to interrogation, and first aid. Continuation Training was followed by jungle training and a static-line parachute course, bringing the complete programme up to six months.

Though Ricketts and the others had all come from regular Army, Royal Navy, RAF or Territorial Army regiments, and were therefore already fully trained soldiers, none of them was prepared for the amount of extra training they had to undergo with the SAS, even after the rigours of Initial Selection.

Weapons training covered everything in the SAS arsenal, including use of the standard-issue British semi-automatic Browning FN 9mm high-power handgun, the 9mm Walther PPK handgun, the M16 assault rifle, the self-loading semi-automatic rifle, or SLR, the Heckler & Koch MP5 sub-machine-gun, the MILAN anti-tank weapon, various mortars and a wide range of ‘enemy’ weapons, such as the Kalashnikov AK-47 assault rifle.

In combat and survival training they were taught the standard operating procedures, or SOPs, for how to move tactically across country by day or night, how to set up and maintain observation posts, or OPs, and how to operate deep behind enemy lines. This led naturally to signals training, covering Morse code, special codes and call-sign systems, the operation of thirty kinds of SAS radio, recognition of radio ‘black spots’, the setting-up of standard and makeshift antennas, and the procedure for calling in artillery fire and air strikes.

As one of the main reasons for being behind enemy lines is the disruption of enemy communications and transportation, as well as general sabotage, particularly against Military Supply Routes, or MSRs, this phase of their training also included lessons in demolition skills and techniques, particularly the use of explosives such as TNT, dynamite, Semtex, Composition C3 and C4 plastic explosive, or PE, Amatol, Pentolite and Ednatol. Special emphasis was laid on the proper placement of charges to destroy various kinds of bridge: cantilever, spandrel arch, continuous-span truss and suspension.

Many jokes were made about the fact that those lessons led directly to instruction in first aid, including relatively advanced medical skills such as setting up an intravenous drip, how to administer drugs, both orally and with injections, and the basics of casualty handling and care.

This phase of Continuation Training culminated in escape and evasion (E&E) and Resistance to Interrogation (RTI) exercises. E&E began with a week of theory on how to live off the land by constructing makeshift shelters from branches, leaves and other local vegetation, and sangars, or semicircular shelters built from stones, and by catching and cooking wild animals. (Repeated jokes about rat stew, Ricketts recalled, had raised a few queasy laughs.) Those theories were then put into practice when the men were dropped off, alone, in some remote region, usually with no more than their clothing and a wristwatch, knife and box of matches, with orders to make their way back to a specified RV without either becoming lost or getting caught by the enthusiastic Parachute Regiment troopers sent out to find them.

Those caught were hooded, bound, thrown into the Paras’ trucks and delivered to the interrogation centre run by the Joint Services Interrogation Unit and members of 22 SAS Training Wing, where various physical and mental torments were used to make them break down and reveal more than their rank, name, serial number and date of birth. Those who did so were failed even at that late stage in the course. Those who managed to remain sane and silent went on to undertake jungle-warfare training and the parachute course.

‘For me,’ Bill said, ‘that was the best bit of all. I loved it in the jungle. I mean, even though it was tough all I could think of was how I’d come all the way from the Stevens and Williams Glassworks to the jungles of fucking Malaysia. I was in heaven, I tell you.’

‘It wasn’t Malaysia,’ Andrew corrected him. ‘It was just close to there. It’s the only British dependency inhabited by Malays that didn’t join the Federation of Malaysia.’

‘He’s so fucking educated,’ Gumboot said, ‘you’d never think he’d been up a tree. What the fuck’s the difference? It was jungle, wasn’t it? That’s why you couldn’t possibly fail there, mate. You must have felt right at home.’

‘My family, comes from Barbados,’ Andrew said, flashing Gumboot a big smile, ‘where they have rum and molasses and white beaches. No jungle there, Gumboot.’

‘Anyway,’ Tom said, looking as solemn as always, ‘I agree with Bill. I was a lot more relaxed when we went there. It was too late to fail, I thought.’

‘So did some others,’ Jock reminded them, ‘and the poor bastards failed. One even failed during the parachute course. Can you fucking believe it?’

‘That would have killed me,’ Ricketts said. ‘I mean, to be RTU’d at that stage. I would have opened a vein.’

‘Hear, hear,’ Andrew said.

Jungle-warfare training was a six-week course in Brunei, the British-protected sultanate of North-West Borneo, forming an enclave with Sarawak, Malaysia, where the SAS was reborn after World War Two and where it learnt so many of its skills and tactics; There the candidates were sent on four-man patrols through the jungle, some lasting almost a fortnight. During that time they had to carry out a number of operational tasks, including constructing a jungle basha, killing and eating wildlife, including snakes, without being bitten or poisoned, and living on local flora and fauna. Most importantly, they had to show that they could navigate and move accurately in the restricted visibility of the jungle. Failure in any of these tasks resulted in an even more cruel, last-minute, RTU.

Those who returned successfully from Brunei did so knowing that they had only one hurdle left: a four-week course at the No 1 Parachute Training School at RAF Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, where Parachute Jump Instructors, or PJIs, taught them the characteristics of PX1 Mk 4, PX1 Mk 5 and PR7 (reserve) parachutes, then supervised them on eight parachute jumps. The first of these was from a static balloon, but the others were from RAF C-130 Hercules aircraft, some from a high altitude, some from a low altitude, most by day, a few by night, and at least one while the aircraft was being put through a series of manoeuvres designed to shake up and disorientate the parachutists just before they jumped out. Those who made this final leap successfully had passed the whole course.

The men drinking around this table in the Paludrine Club had all just done that.

‘I still don’t believe it,’ Andrew mused, ‘but here we all are: in a Sabre Squadron at last. I think that’s reason enough for another drink.’

‘I think you’re right,’ Jock said, going off to the bar for another round.

Once badged, the successful candidates were divided between the four Sabre Squadrons, with those around this table going to Squadron B, where they would spend their probationary first year. They were also allowed into the Paludrine Club to celebrate their success and get to know each other as they had not been able to, or feared to, during the past six months of relentless training and testing.

‘So,’ Gumboot said, raising his glass when Jock had set down the fresh round of drinks. ‘Here’s to all of us, lads.’

They touched their glasses together and drank deeply, trying not to look too proud.

2 (#uf4848077-50ad-5a78-8eb5-43828dc0e07b)

The day after their celebratory booze-up with the other successful troopers, which was followed by a farewell fling with wives and girlfriends in the camp’s Sports and Social Club, the six men allocated to B Squadron were called to the interest room to be given a briefing on their first legitimate SAS mission. As the group was so small, the briefing was not taking place in that room, but in the adjoining office of the Squadron Commander, Major Greenaway. To get to his office, however, the men had to pass through the interest room, which was indeed of interest, being dominated by a horned buffalo head set high on one wall and by the many photographs and memorabilia of previous B Squadron campaigns that covered the other walls, making the room look rather like a military museum.

Andrew was studying photographs of the Malaysia campaign, as well as items of jungle equipment, when a fair-haired SAS sergeant-major, built like a barrel but with no excess fat, appeared in the doorway of Major Greenaway’s office.

‘I’m your RSM,’ he said. ‘The name is Worthington, as befits a worthy man and don’t ever forget it. Now step inside, lads.’

Following the Regimental Sergeant-Major into the office, they were surprised to find one wall completely covered by a blue curtain. Major Greenaway had silvery-grey hair and gazed up from behind his desk with keen, sky-blue eyes and a good-natured smile.

‘You all know who I am,’ he said, standing up by way of greeting, ‘so I won’t introduce myself. I would, however, like to offer you my congratulations on winning the badge and warmly welcome you to B Squadron.’ When the men had murmured their appreciation, Greenaway nodded, turned to the wall behind him and pulled aside the blue curtain, revealing a large, four-colour map of the Strait of Hormuz, showing Muscat and Oman, with the latter boldly circled with red ink and the word ‘SECRET’ stencilled in bold black capital letters across the top.

Greenaway picked up a pointer and tapped the area marked ‘Southern Dhofar’. ‘Oman,’ he said. ‘An independent sultanate in eastern Arabia, located on the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian sea. Approximately 82,000 square miles. Population 750,000 – mainly Arabs, but with substantial Negro blood. A medieval region, isolated from the more prosperous and advanced northern states by a 400-mile desert which rises up at its southern tip into an immense plateau, the Jebel Massif, a natural fortress some 3000 feet high, nine miles wide, and stretching 150 miles from the east down to, and across, the border with Aden, now the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. The Gulf of Oman, about 300 miles long, lies between Oman and Iran, leading through the Strait of Hormuz to the Persian Gulf and the oil wealth of Saudia Arabia. So that’s the place.’

The major lowered the pointer and turned back to face his new men. ‘What’s the situation?’

It was a rhetorical question requiring no answer other than that he was about to give. ‘Oman has long-standing treaties of cooperation with Britain and is strategically important because Middle East oil flows to the West through the Strait of Hormuz. If the communists capture that oil, by capturing Oman, they’ll end up controlling the economy of the Free World. The stakes, therefore, are high.’

Resting the pointer across his knees, Greenaway sat on the edge of his desk. Ricketts, who had worked on the North Sea oil rigs as a toolpusher before joining the regular Army, had been impressed by many of the men he met there: strong-willed, independent, decisive – basically decent. The ‘boss’, who struck him as being just such a man, went on: The situation in Oman has been degenerating since the 1950s with Sultan Said bin Taimur’s repressive regime forcing more and more of the Dhofaris in the south – culturally and ethnically different from the people in the north – into rebellion. After turning against the Sultan, the rebels formed a political party, the Dhofar Liberation Front, or DLF, which the Sultan tried to quell with his Sultan’s Armed Forces, or SAF. The rebels were then wooed and exploited by the pro-Soviet Yemenis, who formed them into the People’s Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf – the PFLOAG. This greatly improved the situation of the rebels, or adoo, and the Sultan’s regime, falling apart, failed to mount an effective counter-insurgency war. Which is where we come in.’

He studied each of the men in turn, checking that he had their full attention and that they all understood him.

‘What’s “adoo” mean, boss?’ Tom asked.

‘It’s the Arabic word for “enemy”,’ Greenaway informed him. ‘Can I continue?’

‘Yes, boss!’

‘The SAF has long had a number of British ex-officers and NCOs as contract advisers, but they were facing a losing battle in the countryside. Exceptionally cruel, punitive actions, such as the public hanging of suspected rebels and the sealing of their life-giving wells, were only turning more of the people against him. As it wasn’t in British interests to let the communists take over Oman, in July last year the Sultan was overthrown by his son, Qaboos, in an almost bloodless coup secretly implemented and backed by us – by which I mean the British government, not the SAS.’

A few of the men laughed drily, causing the major to smile before continuing. ‘However, while Qaboos, with our aid, gradually started winning the hearts of those ostracized by his father’s reactionary regime, the PFLOAG – backed by the Russians, whose eyes are focused firmly on the oil-rich countries of Arabia – continued to make inroads into Oman. Now the adoo virtually control the Jebel Dhofar, which makes them a permanent threat to the whole country.’

Ricketts glanced at the other troopers and saw that they were as keen as he felt. What luck! Instead of Belfast, which was like Britain, only grimmer, they were going to fight their first war in an exotic, foreign country. Childish though it was, Ricketts could not help being excited about that. He had always needed changes of scenery, fresh challenges, new faces – which is why he had first gone to the North Sea, then joined the regular Army. While Belfast might have similar excitements, it was not the same thing. Ricketts was thrilled by the very idea of Oman, which remained a mysterious, perplexing country to air but a few insiders. Also, he was drawn to hot countries and desert terrain. Of course, Maggie would not be pleased and that made him feel slightly guilty. But he could not deny his true nature, which was to get up and go, no matter how much he loved his wife. He felt like a lucky man.

‘What we’re engaged in in Oman,’ the boss continued, ‘is the building of a bulwark against communist expansionism.’ Standing again, he picked up the pointer and turned to the map. ‘That bulwark will be Dhofar,’ he continued, tapping the name with the pointer, ‘in the south of Oman, immediately adjacent to communist-held Aden, now the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. Our job is to back Sultan Qaboos with military aid and advice and to win the hearts of his people by setting up hospitals and schools, by teaching them the skills they need, and by crushing the adoo at the same time. The so-called hearts-and-minds campaign is already in progress, with British Army Training Teams, or BATT, based at Taqa and Mirbat. Our job is to tackle the adoo. Any questions so far?’

‘Yes, boss,’ Ricketts said, already familiar with SAS informality and determined to put it to good use. ‘It’s clearly a laudable aim, but how do we win the military side of it?’

Greenaway smiled. ‘Not everyone considers our aims to be laudable, Trooper. Indeed, Britain has been accused of supporting a cruel, reactionary regime merely to protect its oil interests. While I happen to think that’s the truth, I also believe it’s justified. We must be pragmatic about certain matters, even when our motives aren’t quite laudable.’

‘Yes, boss,’ Ricketts said, returning the major’s wicked grin. ‘So how do we fight the war, apart from winning hearts and minds?’

Greenaway put down the pointer, sat on the edge of the desk, and folded his arms. ‘Since early last year, with the aid of the firqats – bands of Dhofari tribesmen loyal to the Sultan – we’ve managed to gain a few precarious toe-holds on the coastal plain immediately facing the Jebel Dhofar. Now, however, we’re about to launch an operation designed to establish a firm base on the Jebel, from where we can stem the adoo advance. That operation is codenamed Jaguar.’

‘Is this purely an SAS operation?’ Andrew asked, realizing that this was a typical SAS ‘Chinese parliament’, or open discussion.

‘No. In all matters relating to Oman, the SAF and firqats must be seen to be their own men. For this reason, B Squadron and G Squadron will be supporting two companies of the SAF, Dhofari firqats and a platoon of Baluch Askars – tough little buggers from Baluchistan. Nearly 800 fighting men in all.’

‘Are the SAF and the firqats dependable?’ Gumboot asked, gaining the confidence to speak out like the others.

‘Not always. The main problem lies with the firqats, who are volatile by nature and also bound by Islamic restrictions, such as the holy week of Ramadan, when they require a special dispensation to fight. But they have, on occasion, been known to ignore even that. When they fight, they can be ferocious, but they’ll stop at any time for the most trivial reasons – usually arguments over who does what or gets what, or perhaps some imagined insult. So, no, they’re not always dependable.’

‘What about the adoo?’ Ricketts asked.

‘Fierce, committed fighters and legendary marksmen. They can pick a target off at 400 yards and virtually melt back into the mountainside or desert. A formidable enemy.’

‘When does the assault on this Jebel what’s-its-name begin?’ Bill asked, nervously clearing his throat, but determined to be part of this Chinese parliament.

‘About a month from now,’ Greenaway informed him. ‘After you’ve all had a few weeks of training in local customs, language and general diplomacy, including seeing what previous SAS teams have been up to with schools, hospitals and so forth. It’s anticipated that the assault on the…’ – the major looked directly at Trooper Raglan with a tight little smile before pronouncing the name with theatrical precision – ‘Jebel Dhofar will begin on 1 October. The Khareef monsoon, which covers the plateau with cloud and mist from June to September, will be finished by then, which will make the climb easier. Also, according to our intelligence, there’ll be no moon that night, which should help to keep your presence unknown to the adoo.’

‘Who, of course, have the eyes of night owls,’ said Worthington, who had been standing silently behind them throughout the whole briefing. Only when Major Greenaway burst out laughing did the men realize that the RSM was joking. Still not quite used to SAS informality, some of them grinned sheepishly. Worthington managed to wipe the smiles from their faces by adding sadistically: ‘Rumour has it that there are over 2000 adoo on the Jebel. That means the combined SAF and SAS forces will be outnumbered approximately three to one. Should any of you lads think those odds too high, I suggest you hand in your badges right now. Any takers?’ No one said a word, though some shook their heads. ‘Good,’ said the RSM, before turning his attention to Major Greenaway. ‘Anything else, boss?’

‘I think not, Sergeant-Major. This seems to be a healthy bunch of lads and I’m sure they’ll stand firm.’

‘I’m sure they will, boss.’ The RSM looked grimly at the probationers. ‘Go back to the spider and prepare your kit. We fly out tomorrow.’

‘Yes, boss!’ they all sang, practically in unison, then filed out of the office like excited schoolboys.

3 (#uf4848077-50ad-5a78-8eb5-43828dc0e07b)

The four-engined Hercules C-130 took off the following afternoon from RAF Lyneham, refuelled at RAF Akroterion in Cyprus, then flew on to RAF Salalah in Dhofar, where the men disembarked by marching down the tailgate, from the gloom of the aircraft into the blinding, burning furnace of the Arabian sun.

On the runway of RAF Salalah stood Skymaster jets, each in its own sandbagged emplacement and covered by camouflage nets. Three large defensive trenches – encircled by 40-gallon drums and bristling with 25lb guns and 5.5 Howitzers, and therefore known as ‘hedgehogs’ – were laid out to the front and side of the airstrip. Overlooking all was an immense, sun-bleached mountain, its sheer sides rising dramatically to a plateau from the flat desert plain.

‘That must be the Jebel Dhofar,’ Ricketts said to Andrew.

‘It is,’ a blond-haired young man confirmed as he clambered down from the Land Rover that had just driven up to the tailgate. ‘And it’s crawling with heavily-armed adoo. I’m Sergeant Frank Lampton, from one of the BATT teams. ‘I’m here to guide you probationers through your first few days.’ He grinned and glanced back over his shoulder at the towering slopes of the Jebel Dhofar, the summit of which was hazy with the heat. ‘How’d you like to cross-grain the bukits of that?’ he asked, turning back and grinning. ‘Some challenge, eh?’

‘It’d dwarf even the Pen-y-fan,’ Andrew admitted. ‘That’s some mother, man.’

‘Right,’ Lampton said. Slim and of medium height, the sergeant was dressed in shorts, boots with rolled-down socks and a loose, flapping shirt, all of which were covered in the dust that was already starting to cover the new arrivals. A Browning 9mm high-power handgun was holstered on his hip. Squinting against the brilliant sunlight, he pointed to the convoy of armour-plated Bedfords lined up on the edge of the runway. ‘Stretch your legs,’ he told the men, ‘and get used to the heat. When the QM has completed the unloading, pile into those trucks and you’ll be driven to the base at Um al Gwarif. It’s not very far.’

While the men gratefully did stretching exercises, walked about a bit or just sat on their bergens smoking, the Quartermaster Sergeant, a flamboyant Irishman with the lungs of a drill instructor, organized the unloading and sorting of all the squadron’s kit by bawling good-natured abuse at his Omani helpers, all of whom wore shemaghs and the loose robes known as jellabas. The new arrivals watched them with interest.

‘Fucked if I’d like to hump that stuff in this heat,’ Gumboot finally said, breaking the silence.

‘You soon will be,’ Lampton replied with a grin, puffing smoke as he lit a cigarette. ‘You’ll be humping it up that bloody mountain, all the way to the top. That’s why you’d better get used to the heat.’ He inhaled and blew another cloud of smoke, then smiled wryly at Ricketts. ‘Now these Omanis,’ he said, indicating the men unloading the kit and humping it across to the Bedfords, ‘they’d probably down tools if you asked them to do that. That’s why they call the SAS “donkey soldiers” or majnoons – Arabic for “mad ones”. Are they right or wrong, lads?’

‘Anything you say, boss,’ Bill said, ‘is OK by me.’

‘An obedient trooper,’ Lampton replied, flicking ash to the ground. ‘That’s what I like to hear. Which one of you is Trooper Ricketts?’ Ricketts put his hand in the air. ‘I was informed by the RSM that you’re the oldest of the probationers,’ Lampton said.

‘I didn’t know that, boss.’

‘You’re the oldest by one day, I was told, with Trooper McGregor coming right up your backside. That being the case, you’ll be my second-in-command for the next few days. I trust you’ll be able to shoulder this great responsibility.’

Lampton, though a sergeant, was hardly much older than Ricketts, who, feeling confident with him, returned his cocky grin. ‘I’ll do my best, boss.’

‘I’m sure you will, Trooper. The RSM also said you put up a good show at the briefing. Fearless in the presence of your Squadron Commander. Right out front with the questions and so forth. That, also, is why you’ll be in nominal charge of your fellow probationers while you’re under my wing.’

‘This sounds suspiciously like punishment, boss.’

‘It isn’t punishment and it isn’t promotion – it’s a mere convenience. Do you want to beg off?’

‘No, boss.’

‘You gave the correct answer, Trooper Ricketts. You’re a man who’ll go far.’ Glancing towards the Bedfords, Lampton saw that Major Greenaway and RSM Worthington were already allocating the other members of B Squadron to their respective Bedfords. ‘The unloading must be nearly completed,’ Lampton said, dropping his cigarette butt to the tarmac and grinding it out with his heel. ‘OK, Ricketts, collect the other probationers together and follow me to that truck.’

Ricketts did as he had been told, calling in his small group and then following Lampton across to one of the Bedfords parked on the edge of the airstrip. When they were in the rear, cramped together on the hard benches, already covered in a film of dust and being tormented by mosquitoes and fat flies, Lampton joined them, telling another soldier to drive his Land Rover back to base. The Bedford coughed into life, lurched forward, then headed away from the airstrip to a wired-off area containing a single-storey building guarded by local soldiers wearing red berets. The Bedford stopped there.

‘SOAF HQ,’ Lampton explained, meaning the Sultan of Oman’s Air Force. Removing a fistful of documents from the belt of his shorts, he climbed down from the Bedford and went inside.

Forced to wait in the open rear of the crowded Bedford, Ricketts passed the time by examining the area beyond the SOAF HQ. He saw a lot of Strikemaster jet fighters and Skyvan cargo planes in dispersal bays made from empty oil drums. The Strikemasters, he knew from his reading, were armed with Sura rockets, 500lb bombs and machine-guns. The Skyvan cargo planes would be used to resupply, or resup, the SAF and SAS forces when they were up on the plateau, which Ricketts could see in all its forbidding majesty, rising high above the plain of Salalah, spreading out from the camp’s barbed-wire perimeter. The flat, sandy plain was constantly covered in gently drifting clouds of wind-blown dust.

Returning five minutes later with clearance to leave the air base, Lampton climbed back into the Bedford and told the driver to take off. After passing through gates guarded by RAF policemen armed with sub-machine-guns, the truck turned into the road, crossed and bounced off it, then headed along the adjoining rough terrain.

‘What the matter with this clown of a driver?’ Jock McGregor asked. ‘The blind bastard’s right off the road.’

‘It’s deliberate,’ Lampton explained. ‘Most of the roads in Dhofar have been mined by the adoo, so this is the safest way to drive, preferably following previous tyre tracks in case mines have been planted off the road as well. Of course, even that’s no guarantee of safety. Knowing we do this, the adoo often disguise a mine by rolling an old tyre over it to make it look like the tracks of a previous truck. Smart cookies, the adoo.’

All eyes turned automatically towards the road, where the Bedford’s wheels were churning up clouds of dust and leaving clear tracks.

‘Great,’ Gumboot said. ‘You take one step outside your tent and get your fucking legs blown off.’

‘As long as it leaves your balls,’ Andrew said, ‘you shouldn’t complain, man.’

‘Leave my balls out of this,’ Gumboot said. ‘You’ll just put a curse on them.’

‘Any other advice for us?’ Ricketts asked.

‘Yes,’ Lampton replied. ‘Never forget for a minute that the adoo are crack shots. They’re also adept at keeping out of sight. The fact that you can’t see them doesn’t mean they’re not there, and you won’t find better snipers anywhere. You look across a flat piece of desert and think it’s completely empty, then – pop! – suddenly a shot will ring out, compliments of an adoo sniper who’s blended in with the scenery. They can make themselves invisible in this terrain – and they’re bold as brass when it comes to infiltrating us. So never think you’re safe because you’re in your own territory. The truth is that you’re never safe here. You’ve got to assume that adoo snipers are in the vicinity and keep your eyes peeled all the time.’

Again, they glanced automatically at the land they were passing through, seeing only the clouds of dust billowing up behind them, obscuring the sun-scorched flat plain and the immense, soaring sides of the Jebel Dhofar. The sky was a white sheet.

‘Welcome to Oman,’ Tom said sardonically. ‘Land of sunshine and happy, smiling people. Paradise on earth.’

After turning off the road to Salalah, the truck bounced and rattled along the ground beside a dirt track skirting the airfield. About three miles farther on, it came to a large camp surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, with watch-towers placed at regular intervals around its perimeter. Each tower held a couple of armed SAF soldiers, a machine-gun and a searchlight. There were stone-built protective walls, or sangars, manned by RAF guards, on both sides of the main gate.

‘This is Um al Gwarif, the HQ of the SAF,’ Sergeant Lampton explained as the truck halted at the main gate. A local soldier wearing a green shemagh and armed with a 7.62mm FN rifle checked the driver’s papers and then waved the Bedford through. The truck passed another watch-tower as it entered the camp. ‘Home, sweet home, lads.’

Had it not been for the exotic old whitewashed fort, complete with ramparts and slitted windows, located near the centre of the enclosure and flying the triangular red-and-green Omani flag from its highest turret, the place might have been a concentration camp.

‘That’s the Wali’s fort,’ Lampton explained like a tour guide. ‘That’s W-A-L-I. Not wally as you know it. Here, a Wali isn’t an idiot. He’s the Governor of the province. So that’s the Governor’s fort, the camp’s command post. And that,’ he continued, pointing to an old pump house and well just inside the main gate, beyond one of the sangars, ‘is where our running water comes from. Don’t drink it unless you’ve taken your Paludrine. There, behind the well, to the right of those palm trees, is the officers’ mess and accommodations.’ He pointed to the lines of prefabricated huts located near the Wali’s fort. ‘Those are the barracks for the SAF forces. However, you lads, being of greater substance, are relegated to tents.’

He grinned broadly when the men let out loud moans.

As the Bedford headed for the eastern corner of the camp, Ricketts saw that many of the SAF men were gathering outside their barracks, most wearing the same uniform, but with a mixture of red, green, sand and grey berets.

‘The SAF consists of four regiments,’ Lampton explained. ‘The Muscat Regiment, the Northern Frontier Regiment, the Desert Regiment and the Jebel Regiment. That, incidentally, is their order of superiority. While in the barracks, they can be distinguished from each other by their regimental beret. However, in the field they all wear a green, black and maroon patterned head-dress, known as a shemagh. As it’s made of loose cloth and wraps around the face to protect the nose and mouth from dust, you’ll all be given one to wear when you tackle the plateau.’

‘We’ll look like bloody Arabs,’ Bill complained.

‘No bad thing,’ Lampton said. ‘Incidentally, though there are a few Arab SAF officers, most of them are British – either seconded officers on loan from the British Army or contract officers.’

‘You mean mercenaries,’ Andrew objected.

‘They prefer the term “contract officers” and don’t you forget it.’

The Bedford came to a halt in a dusty clearing the size of a football pitch, containing two buildings: an armoury and a radio operations room. Everything else was in tents, shaded by palm trees and separated by defensive slit trenches. One of them was a large British Army marquee, used as the SAS basha, and off to the side were a number of bivouac tents.

The rest of the Bedfords had already arrived and were being unloaded as Ricketts and the others climbed out into fierce heat, drifting dust and buzzing clouds of flies and mosquitoes. Once the all-important radio equipment had been stored in the radio ops room, they picked up their bergens and kit belts and selected one of the large bivouac tents, which contained, as they saw when they entered, only rows of camp-beds covered in mosquito netting and resting on the hard desert floor. After picking a spot, each man unrolled his sleeping bag, using his kit belt as a makeshift pillow. Already bitten repeatedly by mosquitoes, all the men were now also covered in what seemed to be a permanent film of dust.

Even as Ricketts was settling down between Andrew and Gumboot, Lampton came in to tell them that they only had thirty minutes for a rest. ‘Then,’ he said as they groaned melodramatically, ‘you’re to report to the British Army marquee, known here as the “hotel”, for a briefing from the “green slime”.’ This mention of the Intelligence Corps provoked another bout of groans. When it had died down, Lampton added, grinning: ‘And don’t forget to take your Paludrine.’

‘I hear those anti-malaria tablets actually give you malaria,’ Bill said.

‘Take them anyway,’ Lampton said, then left them to their brief rest.

‘What a fucking dump,’ Gumboot said, lying back on his camp bed and waving the flies away from his face. ‘Dust, flies and mosquitoes.’

‘It’s all experience,’ Andrew said, tugging his boots off and massaging his toes. ‘Think of it as an exotic adventure. When you’re old and grey, you’ll be telling your kids about it, saying how great it was.’

‘Exaggerating wildly,’ Jock said from the other side of the tent. ‘A big fish getting bigger.’

Ricketts popped a Paludrine tablet into his mouth and washed it down with a drink from his water bottle. Then, feeling restless, he stood up. ‘No point in lying down for a miserable thirty minutes,’ he said. ‘It’ll just make us more tired than we are now. Half an hour is long enough to get a beer. Who’s coming with me?’

‘Good idea,’ Andrew said, heaving his massive bulk off his camp-bed.

‘Me, too,’ Gumboot said.

The rest followed suit and they all left the tent, walking the short distance to the large NAAFI tent and surprised to see a lot of frogs jumping about the dry, dusty ground. The NAAFI tent had a front wall of polyurethane cartons, originally the packing for weapons. Inside, there were a lot of six-foot tables and benches, at which some men were drinking beer, either from pint mugs or straight from the bottle. A shirtless young man smoking a pipe and sitting near the refrigerator introduced himself as Pete and said he was in charge of the canteen. He told them to help themselves, write their names and what they had had on the piece of paper on top of the fridge, and expect to be billed at the end of each month. All of them had a Tiger beer and sat at one of the tables.

‘So what do you think of the place?’ Pete asked them.

‘Real exotic,’ Gumboot said.

‘It’s not all that bad when you get used to it. I’ve been in worse holes.’

‘Who else is here?’ Ricketts asked.

‘Spooks, Signals, BATT, Ordnance, REME, Catering Corps, Royal Corps of Transport, Engineers.’

‘Spooks, meaning “green slime”,’ Ricketts said.

‘Yes. You’re SAS, right?’

‘Right.’

‘They’ll keep you busy here.’

‘I hope so,’ Andrew said. ‘I wouldn’t want to be bored in this hole. Time would stretch on for ever.’

‘At least we’ve got outdoor movies,’ Pete said, puffing clouds of smoke from his pipe. ‘They’re shown in the SAF camp. English movies one night, Indian ones the next. Just take a chair along with a bottle of beer and have yourself a good time. Me, I’m a movie buff.’

‘I like books,’ Andrew said. ‘I write poetry, see? I always carry a little notebook with me and jot down my thoughts as they come to mind.’

‘What thoughts?’ Gumboot asked.

Andrew shrugged. ‘Thoughts inspired by what I see and hear around me. I rewrite them in my head and jot them down.’

‘You’ve got me in your notebook, have you?’ Jock asked. ‘All my brilliant remarks.’

‘Ask no questions and I’ll tell you no lies,’ Andrew replied with a big grin. ‘It’s just poetry, man.’

‘I didn’t think you could spell,’ Gumboot said, ‘but maybe that doesn’t matter.’

‘Say, man,’ Andrew said, taking a swipe at a dive-bombing hornet trying to get at his beer, ‘how come there’s so many frogs in this desert?’

‘Don’t know,’ Pete said. ‘But there’s certainly a lot of ’em. Frogs, giant crickets, flying beetles, hornets, red and black ants, centipedes, camel spiders and scorpions – you name it, we’ve got it.’

‘Jesus,’ Tom said. ‘Are any of those bastards poisonous?’

‘The centipedes and scorpions can give you a pretty serious sting, so I’d recommend you shake out anything loose before picking it up. Those things like sheltering beneath clothes. They like to hide in boots and shoes. So never pick anything up without shaking it out first.’

‘What about the spiders?’ Bill asked, looking uneasy.

‘They look pretty horrible, but they don’t bite. One has a small body and long legs, the other short legs and a big, fat body. You’ll find them all over the bloody place, including under your bedclothes – another reason for shaking everything out.’

Bill shivered at the very thought of the monsters. ‘I hate spiders!’ he said.

The thunder of 25-pounder guns suddenly shook the tent, taking everyone by surprise.

‘Christ!’ Jock exclaimed. ‘Are we being attacked?’

‘No,’ Pete said. ‘It’s just the SAF firing on the Jebel from the gun emplacements just outside the wire. You’ll get that at regular intervals during the day and even throughout the night, disturbing your sleep. It’s our way of deterring the adoo hiding in the wadis from coming down off the Jebel. It takes some getting used to, but eventually you will get used to it – that and the croaking of the bloody frogs, which also goes on all night.’

‘Time for our briefing,’ Ricketts said. ‘Drink up and let’s go, lads.’ They all downed their beer, thanked Pete, and left the tent. Once outside, Ricketts looked beyond the wire and saw one of the big guns firing from inside its protective ring of 40-gallon drums, located about a hundred yards outside the fence. The noise was tremendous, with smoke and flame belching out of the long barrel. The backblast made dust billow up around the Omani gunners, who had covered their ears with their hands to keep out the noise.

‘That’s one hell of a racket to get used to,’ Jock said.

‘Plug your ears,’ Gumboot told him.

The briefing took place in the corner of the marquee known as the ‘hotel’, where Sergeant Lampton was waiting for them, standing beside another man who, like Lampton, was wearing only a plain shirt, shorts and slippers.

‘Welcome to Um al Gwarif,’ he said. ‘I’m Captain Ralph Banks of SAS Intelligence and I don’t like to hear the term “green slime”.’ When the laughter had died down, he continued: ‘You may have noticed that I’m not wearing my green beret or insignia. You may also have noticed that everyone else around here is like me – no beret, no insignia. There’s a good reason for it. While we’re all here at the Sultan’s invitation, there are those, both here and in Great Britain, who would disapprove of our presence here, so to avoid identification we don’t wear cap badges, identification discs, badges of rank or formation signs. This also means that the adoo won’t know who we are if they capture us, dead or alive. Of course, if they capture you alive, they may try some friendly persuasion, in which case we trust that your interrogation training will stand you in good stead.’

The men glanced at one another, some grinning sheepishly, then returned their attention to the ‘Head Shed’, as senior officers were known.

‘I believe you were briefed in Hereford,’ he said, ‘about the general situation here in Oman.’

‘Yes, boss,’ some of the men replied.

‘Good. What I would like to fill you in on is what you’ll be doing for the next few days, before we make the assault on the Jebel Dhofar and start ousting the adoo.’ Banks turned to the map behind him. ‘As you’ve already been informed, everything that happens here must be seen to be the doing of the Omanis. With our help, the Sultan’s Armed Forces have established bases all around this area. At Taqa,’ he said, pointing the names out on the map, ‘Mirbat and Sudh, all on the coast, and also here in the western area at Akoot, Rayzut, where a new harbour is being built, at Thamrait, or Midway, on the edge of the Empty Quarter, and even on the Jebel itself, at the Mahazair Pools, which will be your first RV when the assault begins.’ He turned back to face them. ‘While the next military objective is the assault on the Jebel, it’s imperative that you men first learn about the workings of the BATT, who assist the SAF with training, advice and community welfare. Also, before you make the assault on the Jebel you’ll have to learn how to deal with the firqats, who can be a prickly, unpredictable bunch.’

He nodded at Sergeant Lampton, who took over the briefing. ‘The firqats are irregular troops formed into small bands led by us. Many of them are former adoo who sided with Sultan Qaboos when he deposed his father and started his reforms. As they know the adoo camps and bases, those particular firqats are very useful, but they aren’t overly fond of the Sultan’s regular army and, as Captain Banks said, they can be very difficult to deal with. For this reason, part of the work of the BATT teams is to be seen doing good deeds, as it were, in the countryside, thus impressing the firqats with our general worthiness and strengthening their support for the Sultan. So it’s imperative that you learn exactly what the BATT teams are doing and how they go about doing it. Therefore, for your first week here, you’ll be split up into small teams, each led by a BATT man, including myself, and given a guided tour of the area, plus special training relating to warfare in this particular environment. At the end of that week, the assault on the Jebel will commence. Any questions?’

There was a brief silence, broken only when Ricketts asked: ‘When do we start?’

‘Tomorrow morning. You have the rest of the day off. As the sun is due to sink shortly, it won’t be a long day. Any more questions?’

As there were no further questions, the group was disbanded and went off to the open mess tent to have dinner at the trestle tables. Afterwards they returned to the NAAFI tent to put in a solid evening’s drinking, returning at midnight, drunk and exhausted, to their bivouac tent. After nervously shaking out their kit to check for scorpions and centipedes, they wriggled into their sleeping bags for what was to prove a restless night punctuated by croaking frogs, irregular blasts from the 25-pounders and attacks by thirsty mosquitoes and dive-bombing hornets. Few of the men felt up to much the next day, but they still had their work to do.

4 (#uf4848077-50ad-5a78-8eb5-43828dc0e07b)

For the next five days, Ricketts, Andrew and Gumboot were driven around the area in Lampton’s Land Rover, with Ricketts driving, the sergeant beside him and the other two in the back with strict instructions to keep their eyes peeled at all times. To ensure that they did not dehydrate, they had brought along a plentiful supply of water bottles and chajugles, small canvas sacks, rather like goatskins, that could be filled with water and hung outside the vehicle to stay cool. Just as the Bedfords had done the first day, Ricketts always drove alongside the roads, rather than on them, to minimize the risk from land-mines laid by the adoo.

The heat was usually fierce, from a sky that often seemed white, but they gradually got used to it, or at least learned to accept it, and they frequently found relief when they drove along the beaches, by the rushing surf and white waves of the turquoise sea. The beaches, they soon discovered, were covered with crabs and lined with wind-blown palm trees. Beyond the trees, soaring up to the white-blue sky, was the towering gravel plateau of the Jebel Dhofar, a constant reminder that soon they would have to climb it – a daunting thought for even the hardiest.

As they drove through the main gates that first morning, the big guns in the hedgehogs just outside the perimeter fired on the Jebel, creating an almighty row, streams of grey smoke and billowing clouds of dust. Just ahead of their Land Rover, a Saladin armoured car was setting out across the dusty plain, right into the clouds of dust.

‘The adoo often mount small raids against us,’ Lampton explained. They also come down from the Jebel during the night to plant mines around the base or dig themselves in for a bit of sniping. That Saladin goes out every morning at this time to sweep the surrounding tracks, clear any mines left and keep an eye out for newly arrived adoo snipers. The same procedure takes place at RAF Salalah, which is where we’re going right now.’

Reversing the same three-mile journey they had made the day before, when they first arrived, with the Land Rover bouncing constantly over the rough gravel-and-sand terrain beside the dirt track, they soon passed the guarded perimeter of RAF Salalah, then came to the main gate by the single-storey SOAF HQ. Their papers were checked by an Omani soldier wearing the red beret of the Muscat Regiment and armed with a 7.62mm FN rifle. Satisfied, he let them drive through the gates and on to where the Strikemaster jets and Skyvan cargo planes were being serviced in the dispersal bays encircled by empty oil drums.

‘Stop right by that open Skyvan,’ Lampton said. When Ricketts had done so, they all climbed down. Lampton introduced them to a dark-haired man wearing only shorts and slippers, whose broad chest and muscular arms were covered in sweat. Though he was wearing no shirt, he carried a Browning 9mm high-power handgun in a holster at his hip. He was supervising the loading of heavy resup bundles into the cargo bay in the rear of the Skyvan. The heavy work was being done by other RAF loadmasters, all of whom were also stripped to the waist and gleaming with sweat.

‘Hi, Whistler,’ Lampton said. ‘How are things?’

‘No sweat,’ Whistler replied.

‘You’re covered in bloody sweat!’

Whistler grinned. ‘No sweat otherwise.’ He glanced at the men standing around Lampton.

‘These bullshit artists have just been badged,’ Lampton said, by way of introduction, ‘and are starting their year’s probationary with us. Men, this is Corporal Harry Whistler of 55 Air Despatch Squadron, Royal Corps of Transport. Though he’s normally based on Thorney Island and was recently on a three-month tour of detachment to the army camp in Muharraq, he’s here to give us resup support. As his surname’s “Whistler” and he actually whistles a lot, we just call him…’

‘Whistler,’ Andrew said.

‘What a bright boy you are.’

Everyone said hello to Whistler. ‘Welcome to the dustbowl,’ he replied ‘I’m sure you’ll have a great time here.’

‘A real holiday,’ Gumboot said.

‘You won’t be seeing too much of Whistler,’ Lampton told them, ‘because he’ll usually be in the sky directly above you, dropping supplies from his trusty Skyvan.’

Grinning, Whistler glanced up at the semi-naked loadmasters, who were now inside the cargo hold, lashing the bundles to the floor with webbing freight straps and 1200lb-breaking-strain cords.

‘What’s in the bundles?’ Rickets asked.

‘Eighty-one-millimetre mortar bombs, HE phosphorus and smoke grenades, 7.62mm ball and belt ammo, compo rations, water in jerrycans – four to a bundle. Those are for the drops to our troopers at places like Simba, Akoot and Jibjat, but we also have food resup for the firqats out in the field, since those bastards are quick to go on strike if they think we’re ignoring them.’ Whistler pointed to some bundles wrapped in plastic parachute bags for extra protection. ‘Tins of curried mutton or fish, rice, flour, spices, dates, and the bloody oil used for the cooking, carried in tins that always burst – hence the parachute bags. As well as all that, we drop the propaganda leaflets that are part of the hearts-and-minds campaign. It’s like being a flying library for the illiterate.’

‘Whistler will also be helping out now and then with a few bombing raids,’ Lampton informed them, ‘though not with your regular weapons, since those are left to the Strikemaster jets.’

‘Right,’ Whistler said. ‘We’re already preparing for the assault on the Jebel.’ He pointed to the six 40-gallon drums lined up on the perimeter track by the runway. ‘We’re going to drop those on the Jebel this afternoon, hopefully on some dumbstruck adoo, as a trial run.’

‘What are they?’ Ricketts asked.

‘Our home-made incendiary bombs. We call them Burmail bombs.’

‘They look like ordinary drums of aviation oil.’

‘That’s just what they are – drums of Avtur. But we dissolve polyurethane in the Avtur to thicken it up a bit; then we seal the drums, fix Schermuly flares to each side of them, fit them with cruciform harnesses and roll them out the back of the Skyvan. They cause a hell of an explosion, lads. Lots of fire and smoke. We use them mainly for burning fields that look like they’ve been cultivated by the adoo. However, if help is required by you lads on the ground, but not available from the Strikemasters, we use the Burmail bombs against the adoo themselves.’

‘Why are they called Burmails?’ asked Andrew, a man with a genuine fondness for words.

‘“Burmail” is an Arabic word for oil drums,’ Whistler told him. ‘Thought by some to be a derivation from Burmah Oil, or the Burmah Oil Company.’

‘What’s it like flying in on an attack in one of those bathtubs?’ Gumboot asked with his customary lack of subtlety.

‘Piece of piss,’ Whistler replied, unperturbed. ‘We cruise in at the minimum safe altitude of 7000 feet, then lose altitude until we’re as low as 500 feet, which we are when we fly right through the wadis on the run in to the DZ. When those fucking Burmail bombs go off, it’s like the whole world exploding. So anytime you need help, just call. That’s what we’re here for, lads.’

On the second day Lampton made Ricketts drive them out to the Salalah plain, where they saw Jebalis taking care of small herds of cattle or carrying their wares, mostly firewood, on camels, en route to Salalah. This reminded the troopers that life here continued as normal; that not only the adoo populated the slopes of the Jebel Dhofar and the arid sand plain in front of it.

That afternoon the group arrived at the old walled town of Salalah. At the main gate they had to wait for ages while the Sultan’s armed guards, the Askouris, searched through the bundles of firewood on the Jebalis’ camels to make sure that their owners were not smuggling arms for the adoo supporters inside the town, of which there were known to be a few. Eventually, when the camels had passed through, the soldiers’ papers were checked, and they were allowed to drive into the town, along a straight track that led through a cluster of mud huts to an oasis of palm trees, lush green grass and running water. They passed the large jail to arrive at the Sultan’s white, fortified palace, where Lampton made Ricketts stop.

‘When Sultan Sa’id Tamur lived there,’ Lampton recounted, ‘he was like a recluse, shunning all Western influence, living strictly by the Koran and ruling the country like a medieval despot. Though his son, Qaboos, was trained at Sandhurst, when he returned here he was virtually kept a prisoner – until he deposed his old man at gunpoint, then sent him into exile in London. He died in the Dorchester Hotel in 1972. A nice way to go.’

‘And by reversing his father’s despotism,’ Andrew said from the back of the Land Rover, ‘Qaboos has gradually been finding favour with the locals.’

‘With our help, yes. He’s been particularly good at increasing recruitment to the army and air force. He’s also built schools and hospitals, plus a radio station whose specific purpose is to combat communist propaganda from Radio Aden. He’s trying to bring Oman into the twentienth century, but I doubt that he’ll get that far. However, if he wins the support of his people and keeps the communists out of Oman, we’ll be content.’

‘Our oil being protected,’ put in Ricketts.

‘That’s right,’ Lampton said. ‘Wait here. I’m going in to give Qaboos a written report on recent events. He likes to be kept informed. When I come out, I’ll give you a quick tour of the town.’

‘It’s more like a bleedin’ village,’ Gumboot complained.

‘It might be a village in Devon,’ Lampton said as he got out of the vehicle, ‘but here it’s a town. Relax, lads. Put your feet up. This could take some time.’

In fact, it took nearly two hours. While Lampton was away, Ricketts and the other two had a smoke, repeatedly quenched their thirst with water from the water bottles and chajugles, and gradually became covered in a slimy film composed of sweat and dust. Already warned to neither stare at, nor talk to, the veiled women who passed by with lowered heads, they amused themselves instead by making faces at some giggling local kids, giving others chewing gum, and practising their basic Arabic with the gendarmes who were indifferently guarding the Sultan’s palace, armed with .303 Short-Magazine Lee Enfield, or SMLE, rifles. When Lampton emerged and again offered them a quick tour of the town, they politely refused.

‘We’ve seen all there is to see,’ Gumboot said, ‘and we’re frying out here, boss. Can we go somewhere cooler?’

Lampton grinned as he took his seat in the Land Rover. ‘OK, lads. Let’s go and see some of the BATT handiwork. That’ll take us along the seashore and help cool you down.’

He guided Ricketts back out through the walled town’s main gates and down to the shore, then made him head for Taqa, halfway between Salalah and Mirbat. The drive did indeed take them along the shore, with the ravishing turquoise sea on one side and rows of palm and date trees on the other. A cool breeze made the journey pleasant, though Ricketts had to be careful not to get stuck in the sand. Also, as he had noticed before, there were a great many crabs, in places in their hundreds, scuttling in both directions across the beach like monstrous ants and being crushed under the wheels of the Land Rover.

‘I get the shivers just looking at ’em,’ Gumboot told them while visibly shivering in the rear of the Land Rover. ‘I’d rather fight the adoo.’

‘There’s a BATT station at Taqa,’ Lampton said, oblivious to the masses of crabs, ‘so you can see the kind of work we do there. You know, of course, that the SAS has been in Oman before.’

‘I didn’t know that,’ Gumboot said to distract himself from the crabs. ‘But then I’m pig-ignorant, boss.’

‘I know they were here before,’ Andrew said, ‘but I don’t know why.’

‘He’s pig-ignorant as well,’ Gumboot said. ‘Now I don’t feel so lonely.’