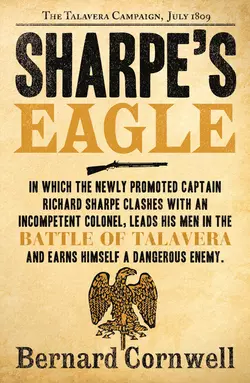

Sharpe’s Eagle: The Talavera Campaign, July 1809

Sharpe’s Eagle: The Talavera Campaign, July 1809

Bernard Cornwell

The newly promoted Captain Richard Sharpe clashes with an incompetent colonel, leads his men in the battle of Talavera and earns himself a dangerous enemy.As Sharpe leads his men in to battle, he knows he must fight for the honour of the regiment and his future career.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.

SHARPE’S

EAGLE

Richard Sharpe and the Talavera

Campaign, July 1809

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

This novel is a work of fiction.The incidents and some of the characters portrayed in it, while based on real historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1981

Previously published in paperback by Fontana 1981

Reprinted twelve times

Copyright © Rifleman Productions Ltd 1981

Map © John Gilkes 2011

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007276240

Ebook Edition © JULY 2009 ISBN: 9780007338641

Version: 2017-05-06

‘Bernard Cornwell set out to create a character who was credible enough to go through many adventures and both Sharpe himself and his Irish sergeant, Patrick Harper, are excellent creations. To my taste, Sharpe is much more interesting than Flashman’

Financial Times

For Judy

‘Every man thinks meanly of himself for not having been a soldier’

SAMUEL JOHNSON

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u880ba3ca-826f-5319-9308-490c74148811)

Copyright (#u68838058-3fa7-5966-912d-b63feb7daf6d)

Dedication (#ue7b57ff8-4360-5738-b692-32cf09325456)

Epigraph (#ua6be070f-3f6d-52d0-95f7-e6a83e6d730f)

Map (#ua8ac2f67-2dab-5eb8-8929-22325b4dd7a6)

Foreword (#ued7e962a-f856-5dea-a1c0-196992140651)

Preface (#ucb352da8-97d7-5e51-a18b-4c7816e65551)

Chapter One (#u1afb2d51-3c43-5eb5-a32d-26c5c74f93f1)

Chapter Two (#u96988c59-7ef3-5695-a1dd-ad13837fd47f)

Chapter Three (#uc3cbce6c-26ad-5d68-887a-3f7c7ecb6a42)

Chapter Four (#u80f3afac-62d2-5908-86d9-71aca3e1debd)

Chapter Five (#u2da0c546-168f-551f-b0bc-5f972ee63aa1)

Chapter Six (#u6380cd45-118a-5530-87c4-a3663fc5e6cd)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Sharpe’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order) (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication) (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Bernard Cornwell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD

This was the first book I wrote, and it is the only book of mine that I have never dared go back and re-read. I still do not dare, for I am sure I would be horrified by the crudity of its writing, but I am constantly told by readers that it is one of their favourites.

It tells the story of the battle of Talavera, which occurred towards the beginning of the Peninsular War. It was not where I wanted to start the Sharpe series. I really wanted to begin with the tale of Badajoz (which turns up in Sharpe’s Company), because Badajoz is such an extraordinary and dramatic event, but I decided it would be a good idea to write a book or two before Badajoz, rather like a bowler warming up before he takes on the opening batsman. I had never written a novel before, never tried to write a novel before, and so Sharpe’s Eagle is where I was going to make all a beginner’s mistakes, and where, if I was successful in my ambition to write a series of tales about the adventures of a British rifleman in the Napoleonic Wars, I was going to learn some of the tricks of the trade. One of the first things I learned was that Sharpe’s enemies, by and large, had to be British. I had thought, before I began writing, that the French would provide him with enemies enough, but the circumstances of war meant that Sharpe spent much more time with the British than with the enemy French, and if he was to be unendingly challenged, irritated, obstructed and angered then the provocations had to come from people with whom he was constantly associated. In time Sharpe is to meet many foul enemies, but few, I think, are as nauseating as Sir Henry Simmerson who, I seem to remember, becomes a tax inspector in his later career.

I said Sharpe’s enemies were British. In fact most of them, like me, are English, while his friends are often Irish. This arose from the happy fact that I had been living in Belfast in the years immediately prior to writing Sharpe and had acquired a fondness for Ireland which has never abated. It also reflected a truth that Wellington’s army was heavily recruited from the Irish, and indeed the Duke (as he was to become) had been born there. That was not a fact of which he was proud. ‘Being born in a stable,’ he once remarked, ‘does not make a man a horse.’ The Duke was a difficult, cold and snobbish man who was also one of the greatest soldiers ever to take the field. Like Sharpe I admire him, but would not particularly wish to dine with him. His story, though, is intimately linked with Sharpe’s, which is to Sharpe’s good fortune. But Sharpe, if he is to make his reputation, must do it with action, rather than by his distant connection with the Duke, and there was no act more admired on a battlefield than the capture of an enemy’s standard. In Napoleon’s army those standards took the form of small statuettes of eagles – thus the book’s title. I decided that if I was not to launch Sharpe against the great walls of Badajoz in his first adventure, then he should face another task just as impossible, and so I set him to capture an eagle. Poor Sharpe.

But there were much greater events resting on his shoulders than the seizing of an eagle. I had fallen in love with Judy, an American to whom the book is dedicated and who, for family reasons, could not live in Britain, which meant I had to earn a crust in the United States if the course of true love was ever to flow smooth. The American Government, in its Simmerson-like wisdom, refused me a work permit so I airily told Judy that I would support us by writing books. Sharpe had to succeed if that irresponsible promise was to be kept. That was twenty-one years ago, and we are still married, so in truth Sharpe’s Eagle is a dazzling romance. And one day I shall read it again.

PREFACE

In 1809 the British army was divided into Regiments, as today, but most Regiments were described by numbers not by names; thus, for instance, the Bedfordshire Regiment was properly called the 14th, the Connaught Rangers the 88th and so on. The soldiers themselves preferred the names but had to wait until 1881 for their official adoption. I have deliberately not given the South Essex, a fictional Regiment, any number.

A Regiment was an administrative unit; the basic fighting unit was the Battalion. Most Regiments consisted of at least two Battalions but a few, like the imaginary South Essex, were small single-Battalion Regiments. That is why, in Sharpe’s Eagle, the two words are used interchangeably of the South Essex. On paper a Battalion was supposed to have about a thousand men but disease and casualties, plus the shortage of recruits, meant that Battalions often went into battle with only five or six hundred troops.

All Battalions were divided into ten companies. Two of these, the Light Company and the Grenadier Company, were the elite of the Battalion and the Light Companies, in particular, were so useful that whole Regiments of Light troops, like the 95th Rifles, were being raised or expanded.

A Battalion was usually commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel, with two Majors, ten Captains, and below them the Lieutenants and Ensigns. None of these officers would have received any formal training; that was reserved for officers of the Engineers and the Artillery. About one officer in twenty was promoted from the ranks. Normal promotion was by seniority rather than merit but a rich man, as long as he had served a minimum period in his rank, could buy his next promotion and thus jump the queue. This system of purchase could lead to very unfair promotions but it is worth remembering that without it Britain’s most successful soldier, Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, would never have risen to high rank early enough in his career to form the most brilliant army Britain has ever possessed; the army in which Richard Sharpe fought the French through Portugal, Spain, and into France between 1808 and 1814.

CHAPTER ONE

The guns could be heard long before they came into sight. Children clung to their mothers’ skirts and wondered what dreadful thing made such noises. The hooves of the great horses mixed with the jangling of traces and chains, the hollow rumbling of the blurring wheels, and above it all the crashes as tons of brass, iron and timber bounced on the town’s broken paving. Then they were in view; guns, limbers, horses and outriders, and the gunners looked as tough as the squat, blackened barrels that spoke of the fighting up north where the artillery had dragged their massive weapons through swollen rivers and up rain-soaked slopes to pound the enemy into oblivion and defeat. Now they would do it again. Mothers held their smallest children and pointed at the guns, boasted that these British would make Napoleon wish he had stayed in Corsica and suckled pigs which was all he was fit for.

And the cavalry! The Portuguese civilians applauded the trotting ranks of gorgeous uniforms, the curved, polished sabres unsheathed for display in Abrantes’ streets and squares, and the fine dust from the horses’ hooves was a small price to pay for the sight of the splendid Regiments who, the townspeople said, would chase the French clean over the Pyrenees and back into the sewers of Paris itself. Who could resist this army? From north and south, from the ports on the western coast, they were coming together and marching east on the road that led to the Spanish frontier and to the enemy. Portugal will be free, Spain’s pride restored, France humbled, and these British soldiers can go back to their own wine-shops and inns leaving Abrantes and Lisbon, Coimbra and Oporto in peace. The soldiers themselves were not so confident. True they had beaten Soult’s northern army but, marching into their lengthening shadows, they wondered what lay beyond Castelo Branco, the next town and the last before the frontier. Soon they would face again the blue-coated veterans of Jena and Austerlitz, the masters of Europe’s battlefields, the French Regiments that had turned the finest armies of the world into so much mincemeat. The townspeople were impressed, at least by the cavalry and artillery, but to experienced eyes the troops gathering round Abrantes were pitifully few and the French armies to the east threateningly big. The British army that awed the children of Abrantes would not frighten the French Marshals.

Lieutenant Richard Sharpe, waiting for orders in his billet on the outskirts of town, watched the cavalry sheath their sabres as the last spectators were left behind and then he turned back to the job of unwinding the dirty bandage from his thigh.

As the last few inches peeled stickily away some maggots dropped to the floor and Sergeant Harper knelt to pick them up before looking at the wound.

‘Healed, sir. Beautiful.’

Sharpe grunted. The sabre cut had become nine inches of puckered scar tissue, clean and pink against the darker skin. He picked off a last fat maggot and gave it to Harper to put safely away.

‘There, my beauty, well fed you are.’ Sergeant Harper closed the tin and looked up at Sharpe. ‘You were lucky, sir.’

That was true, thought Sharpe. The French Hussar had nearly ended him, the man’s blade half way through a massive down-stroke when Harper’s rifle bullet had lifted him from the saddle and the Frenchman’s grimace, framed by the weird pigtails, had turned to sudden agony. Sharpe had twisted desperately away and the sabre, aimed at his neck, had sliced into his thigh to leave another scar as a memento of sixteen years in the British army. It had not been a deep wound but Sharpe had watched too many men die from smaller cuts, the blood poisoned, the flesh discoloured and stinking, and the doctors helpless to do anything but let the man sweat and rot to his death in the charnel houses they called hospitals. A handful of maggots did more than any army doctor, eating away the diseased tissue to let the healthy flesh close naturally. He stood up and tested the leg. ‘Thank you, Sergeant. Good as new.’

‘Pleasure’s all mine, sir.’

Sharpe pulled on the cavalry overalls he wore instead of the regulation green trousers of the 95th Rifles. He was proud of the green overalls with their black leather reinforcement panels, stripped from the corpse of a Chasseur Colonel of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard last winter. The outside of each leg had been decorated with more than twenty silver buttons and the metal had paid for food and drink as his small band of refugee Riflemen had escaped south through the Galician snows. The Colonel had been a lucky kill; there were not many men in either army as tall as Sharpe but the overalls fitted him perfectly and the Frenchman’s soft, rich, black leather boots could have been made for the English Lieutenant. Patrick Harper had not been so fortunate. The Sergeant topped Sharpe by a full four inches and the huge Irishman had yet to find any trousers to replace his faded, patched and tattered pair that were scarcely fit to scare crows in a turnip field. The whole company was like that, reflected Sharpe, their uniforms threadbare, their boots literally tied together with strips of hide, and as long as their parent Battalion was home in England Sharpe’s small company could find no Commissary Officer willing to complicate his account books by issuing them with new trousers or shoes. Sergeant Harper handed Sharpe his uniform jacket. ‘Do you want a Hungarian bath, sir?’

Sharpe shook his head. ‘It’s bearable.’ There were not too many lice in the jacket, not enough to justify steeping it in the smoke from a grass fire and to smell like a charcoal burner for the next two days. The jacket was as worn as those of the rest of his company but nothing, not the best tailored corpse in Portugal or Spain, would have persuaded Sharpe to throw it away. It was green, the dark green jacket of the 95th Rifles, and it was the badge of an elite Regiment. British Infantry wore red, but the best British Infantry wore green, and even after three years in the 95th Sharpe took pleasure in the distinction of the green uniform. It was all he had, his uniform and what he could carry on his back. Richard Sharpe knew no home other than the Regiment, no family except for his company, and no belongings except what fitted into his pack and pouches. He knew no other way to live and expected that it would be the way he would die. Round his waist he tied the red officer’s sash and covered it with the black leather belt with its silver snake buckle. After a year in the Peninsula only the sash and his sword denoted his officer’s rank and even his sword, like the overalls, broke regulations. Officers of the Rifles, like all Light Infantry officers, were supposed to carry a curved cavalry sabre but Sharpe hated the weapon. In its place he wore the long, straight sword of the Heavy Cavalry; a brute of a weapon, ill balanced and crude, but Sharpe liked the feel of a savage blade that could beat down the slim swords of French officers and crush aside a musket and bayonet.

The sword was not his only weapon. For ten years Richard Sharpe had marched in the red-coated ranks, first as a private, then a Sergeant, carrying a smooth-bore musket across the plains of India. He had stood in the line with the heavy flintlock, gone terrified into broken breaches with a bayonet, and he still carried a longarm into battle. The Baker rifle was his mark, it set him aside from other officers, and sixteen-year-old Ensigns, fresh in their bright new uniforms, looked warily at the tall, black-haired Lieutenant with the slung rifle and the scar which, except when he smiled, gave his face a look of grim amusement. Some wondered if the stories were true, stories of Seringapatam and Assaye, of Vimeiro and Lugo, but one glance from the apparently mocking eyes, or a sight of the worn grips on his weapons, stopped the wondering. Few new officers stopped to think of what the rifle really represented, of the fiercest struggle Sharpe had ever fought, the climb from the ranks into the officers’ mess. Sergeant Harper looked out of the window into the square soaked in afternoon sunlight.

‘Here comes Happy, sir.’

‘Captain Hogan.’

Harper ignored the reproof. He and Sharpe had been together too long, shared too many dangers, and the Sergeant knew precisely what liberties he could take with his taciturn officer. ‘He’s looking more cheerful than ever, sir. He must have another job for us.’

‘I wish to God they’d send us home.’

Harper, his huge hands gently stripping the lock of his rifle, pretended not to hear the remark. He knew what it meant but the subject was a dangerous one. Sharpe commanded the remnants of a company of Riflemen who had been cut off from the rearguard of Sir John Moore’s army during its retreat to Corunna the winter before. It had been a terrible campaign in weather that was like the travellers’ tales of Russia rather than northern Spain. Men had died in their sleep, their hair frozen to the ground, while others dropped exhausted from the march and let death overtake them. The discipline of the army had crumbled and the drunken stragglers were easy meat for the French cavalry who flogged their exhausted mounts at the heel of the British army. The rabble was saved from disaster only by the few Regiments, like the 95th, which kept their discipline and fought on. 1808 turned into 1809 and still the nightmarish battle went on, a battle fought with damp powder by freezing men peering through the snow for a glimpse of the cloaked French Dragoons. Then, on a day when the blizzard bellied in the wind like a malevolent monster, the company had been cut off by the horsemen. The Captain was killed, the other Lieutenant, the rifles wouldn’t fire and the enemy sabres rose and fell and the damp snow muffled all sounds except for the grunts of the Dragoons and the terrible chopping of the blades cutting into wounds that steamed in the freezing air. Lieutenant Sharpe and a few survivors fought clear and scrambled into high rocks where horsemen could not follow but when the storm blew out, and the last desperately wounded man died, there was no hope of rejoining the army. The second Battalion of the 95th Rifles had sailed home while Sharpe and his thirty men, lost and forgotten, had headed south, away from the French, to join the small British garrison in Lisbon.

Since then Sharpe had asked a dozen times to be sent home but Riflemen were too scarce, too valuable, and the army’s new commander, Sir Arthur Wellesley, was unwilling to lose even thirty-one. So they had stayed and fought for whichever Battalion needed its Light Company strengthening and had marched north again, retracing their steps, and been with Wellesley when he avenged Sir John Moore by tumbling Marshal Soult and his veterans out of North Portugal. Harper knew his Lieutenant harboured a sullen anger at his predicament. Richard Sharpe was poor, dog poor, and he would never have the money to purchase his next promotion. To become a Captain, even in an ordinary Battalion of the line, would cost Sharpe fifteen hundred pounds and he might as well hope to be made King of France as raise that money. He had only one hope of promotion and that was by seniority in his own Regiment; to step into the shoes of men who died or were promoted and whose own commissions had not been purchased. But as long as Sharpe was in Portugal and the Regiment was home in England he was being forgotten and passed over, time and again, and the unfairness soured Sharpe’s resentment. He watched men younger than himself purchase their Captaincies, their Majorities, while he, a better soldier, was left on the heap because he was poor and because he was fighting instead of being safe home in England.

The door of the cottage banged open and Captain Hogan stepped into the room. He looked, in his blue coat and white trousers, like a naval officer and he claimed his uniform had been mistaken for a Frenchman’s so often that he had been fired on more by his own side than by the enemy. He was an Engineer, one of the tiny number of Military Engineers in Portugal, and he grinned as he took off his cocked hat and nodded at Sharpe’s leg. ‘The warrior restored? How’s the leg?’

‘Perfect, sir.’

‘Sergeant Harper’s maggots, eh? Well, we Irish are clever devils. God knows where you English would be without us.’ Hogan took out his snuff box and inhaled a vast pinch. As Sharpe waited for the inevitable sneeze he eyed the small, middle-aged Captain fondly. For a month his Riflemen had been Hogan’s escort as the Engineer had mapped the roads across the high passes that led to Spain. It was no secret that any day now Wellesley would take the army into Spain, to follow the River Tagus that was aimed like a spear at the capital, Madrid, and Hogan, as well as sketching endless maps, had strengthened the culverts and bridges which would have to take the tons of brass and wood as the field artillery rolled towards the enemy. It had been a job well done in agreeable company, until it rained and the rifles wouldn’t fire and the crazy-eyed French Hussar had nearly made a name for himself by his mad solo charge at the Riflemen. Somehow Sergeant Harper had kept the damp out of his firing pan and Sharpe still shivered when he thought of what might have happened if the rifle had not fired.

The Sergeant collected the pieces of his rifle lock as if he was about to leave but Hogan held up his hand. ‘Stay on, Patrick. I have a treat for you; one that even a heathen from Donegal might like.’ He took a dark bottle out of his haversack and raised an eyebrow to Sharpe. ‘You don’t mind?’

Sharpe shook his head. Harper was a good man, good at everything he did, and in their three years’ acquaintanceship Sharpe and Harper had become friends, or at least as friendly as an officer and a Sergeant could be. Sharpe could not imagine fighting without the huge Irishman beside him, the Irishman dreaded fighting without Sharpe, and together they were as formidable a pair as Hogan had ever seen on a battlefield. The Captain set the bottle on the table and pulled the cork. ‘Brandy. French brandy from Marshal Soult’s own cellars and captured at Oporto. With the compliments of the General.’

‘From Wellesley?’ Sharpe asked.

‘The man himself. He asked after you, Sharpe, and I said you were being doctored or would have been with me.’

Sharpe said nothing. Hogan paused in his careful pouring of the liquid. ‘Don’t be unfair, Sharpe! He’s fond of you. Do you think he’s forgotten Assaye?’

Assaye. Sharpe remembered all right. The field of dead outside the Indian village where he had been commissioned on the battlefield. Hogan pushed a tin cup of brandy across the table to him. ‘You know he can’t make you into a Captain of the 95th. He doesn’t have the power!’

‘I know.’ Sharpe smiled and raised the cup to his lips. But Wellesley did have the power to send him home where promotion might be had. He pushed the thought away, knowing the nagging insult of his rank would soon come back, and was envious of Hogan who, being an Engineer, could only gain promotion by seniority. It meant that Hogan was still only a Captain, even in his fifties, but at least there was no jealousy and injustice because no man could buy his way up the ladder of promotion. He leaned forward. ‘So? Any news? Are we still with you?’

‘You are. And we have a job.’ Hogan’s eyes twinkled. ‘And a wonderful job it is, too.’

Patrick Harper grinned. ‘That means a powerful big bang.’

Hogan nodded. ‘You are right, Sergeant. A big bridge to be blown into the next world.’ He took a map out of his pocket and unfolded it on to the table. Sharpe watched a calloused finger trace the River Tagus from the sea at Lisbon, past Abrantes where they now sat, and on into Spain to stop where the river made a huge southwards loop. ‘Valdelacasa,’ Hogan said. ‘There’s an old bridge there, a Roman one. The General doesn’t like it.’

Sharpe could see why. The army would march on the north bank of the Tagus towards Madrid and the river would guard their right flank. There were few bridges where the French might cross and harass their supply lines and those bridges were in towns, like Alcantara, where the Spanish kept garrisons to protect the crossings. Valdelacasa was not even marked. If there was no town there would be no garrison and a French force could cross and play havoc in the British rear. Harper leaned over and looked at the map.

‘Why isn’t it marked, sir?’

Hogan made a contemptuous noise. ‘I’m surprised the map even marks Madrid, let alone Valdelacasa.’ He was right. The Tomas Lopez map, the only one available to the armies in Spain, was a wondrous work of the Spanish imagination. Hogan stabbed his finger down on to the map. ‘The bridge is hardly used, it’s in bad repair. We’re told you can hardly put a cart across, let alone a gun, but it could be repaired and we could have “old trousers” up our backsides in no time.’ Sharpe smiled. ‘Old trousers’ was the Rifles’ strange nickname for the French and Hogan had adopted the phrase with relish. The Engineer lowered his voice conspiratorially. ‘It’s a strange place, I’m told, just a ruined convent and the bridge. They call it El Puente de los Malditos.’ He nodded as if he had made his point.

Sharpe waited a few seconds and sighed. ‘All right. What does it mean?’

Hogan smiled triumphantly. ‘I’m surprised you need to ask! It means “The Bridge of the Accursed”. It seems that, years ago, all the nuns were taken out of the convent and massacred by the Moors. It’s haunted, Sharpe, stalked by the spirits of the dead!’

Sharpe leaned forward to peer more closely at the map. Give or take the width of Hogan’s finger the bridge must be sixty miles beyond the border and they were that far from Spain already. ‘When do we leave?’

‘Now there’s a problem.’ Hogan folded the map carefully. ‘We can leave for the frontier tomorrow but we can’t cross until we’re formally invited by the Spanish.’ He leaned back with his cup of brandy. ‘And we have to wait for our escort.’

‘Escort!’ Sharpe bridled. ‘We’re your escort.’

Hogan shook his head. ‘Oh, no. This is politics. The Spanish will let us blow up their bridge but only if a Spanish Regiment goes along with us. It’s a question of pride, apparently.’

‘Pride!’ Sharpe’s anger was obvious. ‘If you have a whole Regiment of Spaniards then why the hell do you need us?’

Hogan smiled placatingly. ‘Oh, I need you. There’s more, you see.’ He was interrupted by Harper. The Sergeant was standing at the window, oblivious of their conversation, and staring into the small square.

‘That is nice. Oh, sir, that can clean my rifle any day of the week.’

Sharpe looked through the small window. Outside, on a black mare, sat a girl dressed in black; black breeches, black jacket, and a wide-brimmed hat that shadowed her face but in no way obscured a beauty that was startling. Sharpe saw a wide mouth, dark eyes, coiled hair the colour of fine powder and then she became aware of their scrutiny. She half smiled at them and turned away, snapped an order at a servant holding the halter of a mule, and stared at the road leading from the plaza towards the centre of Abrantes. Hogan made a small, contented noise. ‘That is special. They don’t come out like that very often. I wonder who she is?’

‘Officer’s wife?’ Sharpe suggested.

Harper shook his head. ‘No ring, sir. But she’s waiting for someone, lucky bastard.’

And a rich bastard, thought Sharpe. The army was collecting its customary tail of women and children who followed the Regiments to war. Each Battalion was allowed to take sixty soldiers’ wives to an overseas war but no one could stop other women joining the ‘official’ wives; local girls, prostitutes, seamstresses and washerwomen, all making their living from the army. This girl looked different. There was the smell of money and privilege about her as if she had run away from a rich Lisbon home. Sharpe presumed she was the lover of a rich officer, as much a part of his equipment as his thoroughbred horses, his Manton pistols, his silver dinnerware for camp meals, and the hounds that would trot obediently at his horse’s tail. There were plenty of girls like her, Sharpe knew, girls who cost a lot of money, and he felt the old envy rise in him.

‘My God.’ Harper, still staring out of the window, had spoken again.

‘What is it?’ Sharpe leaned forward and, like his Sergeant, he could hardly believe his eyes. A Battalion of British Infantry was marching steadily into the square but a Battalion the like of which Sharpe had not seen for more than twelve months. A year in Portugal had turned the army into a Drill-Sergeant’s nightmare, the soldiers’ uniforms had faded and been patched with the ubiquitous brown cloth of the Portuguese peasants, their hair had grown long, the polish had long disappeared from buttons and badges. Sir Arthur Wellesley did not mind; he only cared that a soldier had sixty rounds of ammunition and a clear head and if his trousers were brown instead of white then it made no difference to the outcome of a fight. But this Battalion was fresh from England. Their coats were a brilliant scarlet, their crossbelts pipeclayed white, their boots a mirror-surfaced black. Each man wore tightly-buttoned gaiters and, even more surprising, they still wore the infamous stocks; four inches of stiffly varnished black leather that constricted the neck and was supposed to keep a man’s chin high and back straight. Sharpe could not remember when he had last seen a stock; once on campaign the men ‘lost’ them, and with them went the running sores where the rigid leather dug into the soft flesh beneath the jawbone.

‘They’ve taken the wrong turning for Windsor Castle,’ Harper said.

Sharpe shook his head. ‘They’re unbelievable!’ Whoever commanded this Battalion must have made the men’s lives hell to keep them looking so immaculate despite the voyage from England in cramped and foul ships and the long march from Lisbon in the summer heat. Their weapons shone, their equipment was pristine and regular while their faces bulged red from the constricting stocks and the unaccustomed sun. At the head of each company rode the officers, all, Sharpe noted, mounted superbly. The colours were cased in polished leather and guarded by Sergeants whose halberd blades had been burnished to a brilliant, glittering sheen. The men marched in perfect step, looking neither right nor left, for all the world, as Harper had said, as if they were marching for the Royal duty at Windsor.

‘Who are they?’ Sharpe was trying to think of the Regiments who had yellow facings on their uniforms but this looked like none of the Regiments he knew.

‘The South Essex,’ Hogan said.

‘The who?’

‘The South Essex. They’re new, very new. Just raised by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry Simmerson, a cousin of General Sir Banestre Tarleton.’

Sharpe whistled softly. Tarleton had fought in the American war and now sat in Parliament as Wellesley’s bitterest military opponent. Sharpe had heard said that Tarleton wanted the command of the army in Portugal for himself and bitterly resented the younger man’s preferment. Tarleton was a man of influence, a dangerous enemy for Wellesley, and Sharpe knew enough about the politics of high command to realise that the presence of Tarleton’s cousin in the army would not be welcomed by Wellesley.

‘Is that him?’ He pointed to a portly man riding a grey horse in the centre of the Battalion.

Hogan nodded. ‘That is Sir Henry Simmerson, whom God preserve or preferably not.’

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry Simmerson had a red face lined with purple veins and pendulous with jowls. His eyes, at the distance Sharpe was seeing them, seemed small and red, and on either side of the suspicious, questing face there sprung prominent ears that looked like the protruding trunnions either side of a cannon barrel. He looked, Sharpe thought, like a pig on horseback. ‘I’ve not heard of the man.’

‘That’s not surprising. He’s done nothing.’ Hogan was scornful. ‘Landed money, in Parliament for Paglesham, justice of the peace and, God help us, a Militia Colonel.’ Hogan seemed surprised by his own lack of charity. ‘He means well. He won’t be content till those lads are the best damned Battalion in the army but I think the man has a terrible shock coming when he finds the difference between us and the Militia.’

Like other Regular officers Hogan had little time for the Militia, Britain’s second army. It was used exclusively within Britain itself, never had to fight, never went hungry, never slept in an open field beneath a cloudburst, yet it paraded with a glorious pomp and self-importance. Hogan laughed. ‘Mustn’t complain. We’re lucky to have Sir Henry.’

‘Lucky?’ Sharpe looked at the greying Engineer.

‘Oh, yes. Sir Henry only arrived in Abrantes yesterday but he tells us he’s a great expert on war. The man’s not yet seen a Frenchman but he’s lectured the General on how to beat them!’ Hogan laughed and shook his head. ‘Maybe he’ll learn. One battle could take the starch out of him.’

Sharpe looked at the companies marching steadily through the square like automatons. The brass badges on their shakoes reflected the sun but the faces beneath the brilliance were expressionless. Sharpe loved the army, it was his home, the refuge that an orphan had needed sixteen years before, but he liked it most of all because it gave him, in a clumsy way, the opportunity to prove again and again that he was valued. He could chafe against the rich and the privileged but he acknowledged that the army had taken him from the gutter and put an officer’s sash round his waist and Sharpe could think of no other job that would offer a low-born bastard on the run from the law the chance of rank and responsibility. But Sharpe had also been lucky. In sixteen years he had rarely stopped fighting and it had been his fortune that the battles in Flanders, India and Portugal had called for men like himself who reacted to danger the way a gambler reacted to a deck of cards. Sharpe suspected he would hate the peacetime army, with its church parades and pointless drills, its petty jealousies and endless polish, and in the South Essex he saw the peacetime army he did not want. ‘I suppose he’s a flogger?’

Hogan grimaced. ‘Floggings, punishment parades, extra drills. You name it and Sir Henry uses it. He will have, he says, only the best. And they are. What do you think of them?’

Sharpe laughed grimly. ‘God keep me from the South Essex. That’s not too much to ask, is it?’

Hogan smiled. ‘I’m afraid it is.’

Sharpe looked at him, a sinking feeling in his stomach. Hogan shrugged. ‘I told you there was more. If a Spanish Regiment marches to Valdelacasa then Sir Arthur feels, for the sake of diplomacy, that a British one should go as well. Show the flag; that kind of thing.’ He glanced at the polished ranks and back to Sharpe. ‘Sir Henry Simmerson and his fine men are going with us.’

Sharpe groaned. ‘You mean we have to take orders from him?’

Hogan pursed his lips. ‘Not exactly. Strictly speaking you will take your orders from me.’ He had spoken primly, like a lawyer, and Sharpe glanced at him curiously. There could be only one reason why Wellesley had subordinated Sharpe and his Riflemen to Hogan, instead of to Simmerson, and that was because the General did not trust Sir Henry. Sharpe still wondered why he was needed; after all Hogan could expect the protection of two whole Battalions, at least fifteen hundred men. ‘Does the General expect there to be a fight?’

Hogan shrugged. ‘He doesn’t know. The Spanish say that the French have a whole Regiment of cavalry on the south bank, with horse artillery, who’ve been chasing Guerilleros up and down the river since spring. Who knows? He thinks they may try to stop us blowing the bridge.’

‘I still don’t understand why you need us.’

Hogan smiled. ‘Perhaps I don’t. But there won’t be any action for a month; the French will let us go deep into Spain before they fight, so Valdelacasa will at least be the chance of a scramble. And I want someone with me I can trust. Perhaps I just want you along as a favour?’

Sharpe smiled. Some favour, wet-nursing a Militia Colonel who thought he knew it all, but he hid his feelings. ‘For you, sir, it will be a pleasure.’

Hogan smiled back. ‘Who knows? It might be. She’s going along.’ Sharpe followed Hogan’s gaze out of the window and saw the black-dressed girl raise a hand to an officer of the South Essex. Sharpe had an impression of a blond man, immaculately uniformed, mounted on a horse that had probably cost more than the rider’s commission. The girl spurred her mare forward and, followed by the servant and his mule, joined the rear of the Battalion that was marching down the road that led to Castelo Branco. The square became empty again, the dust settling in the fierce heat, and Sharpe leaned back and began to laugh.

‘What’s so funny?’ Hogan asked.

Sharpe pointed with his cup of brandy at Harper’s tattered jacket and gaping trousers. ‘Sir Henry’s not exactly going to be fond of his new allies.’

The Sergeant’s face stayed gloomy. ‘God save Ireland.’

Hogan raised his cup. ‘Amen to that.’

CHAPTER TWO

The drumbeats were distant and muffled, sometimes blending with the other sounds of the city, but insistent and sinister and Sharpe was glad when the sound stopped. He was also glad they had reached Castelo Branco, twenty-four hours after the South Essex, after a tiresome journey that had consisted of forcing Hogan’s mules along a road cut with deep, jagged ruts showing where the field artillery had gone before them. Now the mules, laden with powder kegs, oilskin packets of match-fuse, picks, crowbars, spades, all the equipment Hogan needed for Valdelacasa, followed patiently behind the Riflemen and Hogan’s artificers as they pushed their way through the crowded streets towards the main square. As they spilled into the bright sunlight Sharpe’s suspicions about the drumbeats were confirmed.

Someone had been flogged. It was over now. The victim had gone and Sharpe, watching the hollow square formation of the South Essex, remembered his own flogging, years before, and the struggle to keep the agony shut up, not to show to the officers that the lash hurt. Sharpe would carry the scars of his flogging to his grave but he doubted whether Simmerson knew how savage was the punishment he had just meted to his Battalion.

Hogan reined in his horse in the shade of the Bishop’s palace. ‘This doesn’t seem to be the best moment to talk to the good Colonel.’ Soldiers were taking down four wooden triangles that were propped against the far wall of the square. Four men flogged. Dear God, thought Sharpe, four men. Hogan turned his horse so that his back was to the Battalion. ‘I must lock up the powder, Richard. Otherwise every bloody grain will be stolen. I’ll meet you back here.’

Sharpe nodded. ‘I need water anyway. Ten minutes?’

Sharpe’s men collapsed at the foot of the wall, their packs and rifles discarded, their mood soured by the reminder before them of a discipline the Rifle Regiments had virtually discarded. Sir Henry rode his horse delicately to the centre of the square and his voice carried clearly to Sharpe and his men.

‘I have flogged four men because four men deserted.’ Sharpe looked up, startled. Deserters already? He looked at the Battalion, their faces expressionless, and wondered how many others were tempted to escape from Simmerson’s ranks. The Colonel was half standing in his saddle. ‘Some of you know how those men planned their crime. Some of you helped them. But you preferred silence so I have flogged four men to remind you of your duty.’ His voice was curiously high pitched; it would have been funny if the man’s presence was not so big. He had been speaking in a controlled manner, almost conversationally, but suddenly Sir Henry turned left and right and waved an arm as if to point at every man in his command. ‘You will be the best!’ The loudness was so sudden that pigeons burst startled from the ledges of the convent. Sharpe waited for more, but there was none, and the Colonel turned his horse and rode away leaving the battle cry lingering behind like a menace.

Sharpe caught Harper’s eye and the Sergeant shrugged. There was nothing to be said, the faces of the South Essex proclaimed Simmerson’s failure; they simply did not know how to be the best. Sharpe watched as the companies marched from the plaza and saw only sullenness and resentment in their expressions. Sharpe believed in discipline. Desertion to the enemy deserved death, some offences deserved a flogging, and if a man was hung for blatant looting then it was his fault because the rules were simple. And for Sharpe, that was the key; keep the rules simple. He asked three things of his men. That they fought, as he did, with a ruthless professionalism. That they stole only from the enemy and the dead unless they were starving. And that they never got drunk without his permission. It was a simple code, understandable by men who had mostly joined the army because they had failed elsewhere, and it worked. It was backed by punishment and Sharpe knew, for all that his men liked him and followed him willingly, that they feared his anger when they broke his trust. Sharpe was a soldier.

He crossed the square towards an alleyway, looking for a water fountain, and noticed a Lieutenant of the South Essex’s Light Company riding his horse towards the same dark-shadowed gap between the buildings.

It was the man who had waved to the black-dressed girl and Sharpe felt a stab of irritation as he entered the alley first. It was an irrational jealousy. The Lieutenant’s uniform was elegantly tailored, the Light Infantry curved sabre was expensive, and the black horse he rode was probably worth a Lieutenant’s commission by itself. Sharpe resented the man’s wealth, his privilege, the easy superiority of a man born to the landed gentry, and it annoyed Sharpe because he knew that resentment was based on envy. He squeezed into the side of the alley to let the horseman pass, looked up and nodded affably, and had an impression of a thin, handsome face fringed with blond hair. He hoped the Lieutenant would ignore him; Sharpe was bad at small talk and he had no wish to make stilted conversation in a foetid alley when he would doubtless be introduced to the Battalion’s officers later in the day.

Sharpe was disappointed. The Lieutenant stopped and stared down at the Rifleman. ‘Don’t they teach you to salute in the Rifles?’ The Lieutenant’s voice was as smooth and rich as his uniform. Sharpe said nothing. His epaulette was missing, torn off in the winter’s fighting, and he realised that the blond Lieutenant had mistaken him for a private. It was hardly surprising. The alleyway was deeply shadowed, Sharpe’s profile, with slung rifle, all helped to explain the Lieutenant’s mistake. Sharpe glanced up to the thin, blue-eyed face and was about to explain when the Lieutenant flicked his whip so that it slapped Sharpe’s face.

‘Damn you, man, answer me!’

Sharpe felt the anger rise in him, but stayed still and waited for his moment. The Lieutenant drew the whip back.

‘What Battalion? What company?’

‘Second Battalion, Fourth Company.’ Sharpe spoke with deliberate insolence and remembered the days when he had no protection against officers like this. The Lieutenant smiled again, no more pleasantly.

‘You will call me “sir” you know. I shall make you. Who’s your officer?’

‘Lieutenant Sharpe.’

‘Ah!’ The Lieutenant kept his whip raised. ‘Lieutenant Sharpe who we’ve all been told about. Came up from the ranks, didn’t he?’

Sharpe nodded and the Lieutenant drew the whip back further.

‘Is that why you don’t say “sir”? Has Mr Sharpe strange ideas on discipline? Well, I will have to see Lieutenant Sharpe, won’t I, and arrange to have you punished for insolence.’ He brought the whip slashing down towards Sharpe’s head. There was no room for Sharpe to step back, but there was no need, instead he put both hands under the man’s stirrup and heaved upwards with all his strength. The whip stopped somewhere in mid stroke, the man started to cry out, and the next instant he was flat on his back on the far side of his horse where another horse had dunged earlier.

‘You’re going to have to wash your uniform, Lieutenant.’ Sharpe smiled.

The man’s horse had whinnied and gone forward a few paces and the furious Lieutenant struggled to his feet and put his hand to the hilt of his sabre.

‘Hello there!’ Hogan was peering into the alley. ‘I thought I’d lost you!’ The Engineer rode his horse up to the two men and stared cheerfully down on the Rifleman. ‘Mules all stabled, powders locked up.’ He turned to the strange Lieutenant and raised his hat. ‘Afternoon. Don’t think we’ve met. My name’s Hogan.’

The Lieutenant let go of his sword. ‘Gibbons, sir. Lieutenant Christian Gibbons.’

Hogan grinned. ‘I see you’ve already met Sharpe. Lieutenant Richard Sharpe of the 95th Rifles.’

Gibbons looked at Sharpe and his eyes widened as he noticed, for the first time, that the sword hanging by Sharpe’s side was not the usual sword-bayonet carried by Riflemen but was a full-length blade. He raised his eyes to look nervously at Sharpe’s. Hogan went cheerfully on. ‘You’ve heard of Sharpe, of course; everyone has. He’s the laddie who killed the Sultan Tippoo. Then, let me see, there was that ghastly affair at Assaye. No one knows how many Sharpe killed there. Do you know, Sharpe?’ Hogan ignored any possible answer and ground on remorselessly. ‘Terrible fellow, our Lieutenant Sharpe, equally fatal with a sword or gun.’

Gibbons could hardly mistake Hogan’s message. The Captain had seen the scuffle and was warning Gibbons about the likely consequence of a formal duel. The Lieutenant took the proffered escape. He bent down and picked up his Light Company shako then nodded to Sharpe.

‘My mistake, Sharpe.’

‘My pleasure, Lieutenant.’

Hogan watched Gibbons retrieve his horse and disappear from the alleyway. ‘You’re not very gracious at receiving an apology.’

‘It wasn’t very graciously given.’ Sharpe rubbed his cheek. ‘Anyway, the bastard hit me.’

Hogan laughed incredulously. ‘He what?’

‘Hit me, with his whip. Why do you think I dumped him in the manure?’

Hogan shook his head. ‘There’s nothing so satisfying as a friendly and professional relationship with your fellow officers, my dear Sharpe. I can see this job will be a pleasure. What did he want?’

‘Wanted me to salute him. Thought I was a private.’

Hogan laughed again. ‘God knows what Simmerson will think of you. Let’s go and find out.’

They were ushered into Simmerson’s room to find the Colonel of the South Essex sitting on his bed wearing nothing but a pair of trousers. A doctor knelt beside him who looked up nervously as the two officers came into the room; the movement prompted an impatient flap of Simmerson’s hand. ‘Come on, man, I haven’t all day!’

In his hand the doctor was holding what appeared to be a metal box with a trigger mounted on the top. He hovered it over Sir Henry’s arm and Sharpe saw he was trying to find a patch of skin that was not already scarred with strangely regular marks.

‘Scarification!’ Sir Henry barked to Hogan. ‘Do you bleed, Captain?’

‘No, sir.’

‘You should. Keeps a man healthy. All soldiers should bleed.’ He turned back to the doctor who was still hesitating over the scarred forearm. ‘Come on, you idiot!’

In his nervousness the doctor pressed the trigger by mistake and there was a sharp click. From the bottom of the box Sharpe saw a group of wicked little blades leap out like steel tongues. The doctor flinched back. ‘I’m sorry, Sir Henry. A moment.’

The doctor forced the blades back into the box and Sharpe suddenly realised that it was a bleeding machine. Instead of the old-fashioned lancet in the vein Sir Henry preferred the modern scarifier that was supposed to be faster and more effective. The doctor placed the box on the Colonel’s arm, glanced nervously at his patient, then pressed the trigger.

‘Ah! That’s better!’ Sir Henry closed his eyes and smiled momentarily. A trickle of blood ran down his arm and escaped the towel that the doctor was dabbing at the flow.

‘Again, Parton, again!’

The doctor shook his head. ‘But, Sir Henry …’

Simmerson cuffed the doctor with his free hand. ‘Don’t argue with me! Damn it, man, bleed me!’ He looked at Hogan. ‘Always too much spleen after a flogging, Captain.’

‘That’s very understandable, sir,’ Hogan said in his Irish brogue and Simmerson looked at him suspiciously. The box clicked again, the blades gouged into the plump arm, and more blood trickled on to the sheets. Hogan caught Sharpe’s eye and there was the glimmer of a smile that could too easily turn into laughter. Sharpe looked back to Sir Henry Simmerson who was pulling on his shirt.

‘You must be Captain Hogan?’

‘Yes, sir.’ Hogan nodded amiably.

Simmerson turned to Sharpe. ‘And who the devil are you?’

‘Lieutenant Sharpe, sir. 95th Rifles.’

‘No, you’re not. You’re a damned disgrace, that’s what you are!’

Sharpe said nothing. He stared over the Colonel’s shoulder, through the window, at the far blue hills where the French were gathering their strength.

‘Forrest!’ Simmerson had stood up. ‘Forrest!’

The door opened and the Major, who must have been waiting for the summons, came in. He smiled timorously at Sharpe and Hogan and then turned to Simmerson. ‘Colonel?’

‘This officer will need a new uniform. Provide it, please, and arrange to have the money deducted from his pay.’

‘No.’ Sharpe spoke flatly. Simmerson and Forrest turned to stare at him. For a moment Sir Henry said nothing, he was not used to being contradicted, and Sharpe kept going. ‘I am an officer of the 95th Rifles and I will wear their uniform so long as I have that honour.’

Simmerson began to go red and his fingers fluttered at his side. ‘Damn you, Sharpe! You’re a disgrace! You’re not a soldier, you’re a crossing sweeper! You’re under my orders now and I’m ordering you to be back here in fifteen minutes …’

‘No, sir.’ This time Hogan had spoken. His words checked Simmerson in full flow but the Captain gave the Colonel no time to recover. He unleashed all his Irish charm, starting with a smile of such sweet reasonableness that it would have charmed a fish out of the water. ‘You see, Sir Henry, Sharpe is under my orders. The General is quite specific. As I understand it, Sir Henry, we accompany each other to Valdelacasa but Sharpe is with me.’

‘But …’ Hogan raised a hand to Simmerson’s protest.

‘You are right, sir, so right. But of course you would understand that conditions in the field may not be all that we would want and it may be as well, sir, I need hardly tell you, that I should have the dispositions of the Riflemen.’

Simmerson stared at Hogan. The Colonel had not understood a word of Hogan’s nonsense but it had all been stated in such a matter-of-fact way, and in such a soldier-to-soldier way, that Simmerson was desperately trying to find an answer that did not make him sound foolish. He looked at Hogan for a moment. ‘But that would be my decision!’

‘How right you are, sir, how true!’ Hogan spoke emphatically and warmly. ‘Normally, that is. But I think the General had it in his mind, sir, that you would be so burdened with the problems of our Spanish allies and then, sir, there are the exigencies of engineering that Lieutenant Sharpe understands.’ He leaned forward conspiratorially. ‘I need men to fetch and carry, sir. You understand.’

Simmerson smiled, then gave a bray of a laugh. Hogan had taken him off the hook. He pointed at Sharpe. ‘He dresses like a common labourer, eh, Forrest? A labourer!’ He was delighted with his joke and repeated it to himself as he pulled on his vast scarlet and yellow jacket. ‘A labourer! Eh, Forrest?’ The Major smiled dutifully. He resembled a long-suffering vicar continually assailed by the sins of an unrepentant flock and when Simmerson’s back was turned he gave Sharpe an apologetic look. Simmerson buckled his belt and turned back to Sharpe. ‘Done much soldiering then, Sharpe? Apart from fetching and carrying?’

‘A little, sir.’

Simmerson chuckled. ‘How old are you?’

‘Thirty-two, sir.’ Sharpe stared rigidly ahead.

‘Thirty-two, eh? And still only a Lieutenant? What’s the matter, Sharpe? Incompetence?’

Sharpe saw Forrest signalling to the Colonel but he ignored the movements. ‘I joined in the ranks, sir.’

Forrest dropped his hand. The Colonel dropped his mouth. There were not many men who made the jump from Sergeant to Ensign and those who did could rarely be accused of incompetence. There were only three qualifications that a common soldier needed to be given a commission. First he must be able to read and write and Sharpe had learned his letters in the Sultan Tippoo’s prison to the accompaniment of the screams of other British prisoners being tortured. Secondly the man had to perform some act of suicidal bravery and Sharpe knew that Simmerson was wondering what he had done. The third qualification was extraordinary luck and Sharpe sometimes wondered whether that was not a two-edged sword. Simmerson snorted.

‘You’re not a gentleman then, Sharpe?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Well you could try to dress like one, eh? Just because you grew up in a pigsty that doesn’t mean you have to dress like a pig?’

‘No, sir.’ There was nothing else to say.

Simmerson slung his sword over his vast belly. ‘Who commissioned you, Sharpe?’

‘Sir Arthur Wellesley, sir.’

Sir Henry gave a bray of triumph. ‘I knew it! No standards, no standards at all! I’ve seen this army, its appearance is a disgrace! You can’t say that of my men, eh? You cannot fight without discipline!’ He looked at Sharpe. ‘What makes a good soldier, Sharpe?’

‘The ability to fire three rounds a minute in wet weather, sir.’ Sharpe invested his answer with a tinge of insolence. He knew the reply would annoy Simmerson. The South Essex was a new Battalion and he doubted whether its musketry was up to the standard of other, older Battalions. Of all the European armies only the British practised with live ammunition but it took weeks, sometimes months, for a soldier to learn the complicated drill of loading and firing a musket fast, ignoring the panic, just concentrating on out-shooting the enemy.

Sir Henry had not expected the answer and he stared thoughtfully at the scarred Rifleman. To be honest, and Sir Henry did not enjoy being honest with himself, he was afraid of the army he had encountered in Portugal. Until now Sir Henry had thought soldiering was a glorious affair of obedient men in drill-straight lines, their scarlet coats shining in the sun, and instead he had been met by casual, unkempt officers who mocked his Militia training. Sir Henry had dreamed of leading his Battalion into battle, mounted on his charger, sword aloft, gaining undying glory. But staring at Sharpe, typical of so many officers he had met in his brief time in Portugal, he found himself wondering whether there were any French officers who looked like Sharpe. He had imagined Napoleon’s army as a herd of ignorant soldiers shepherded by foppish officers and he shuddered inside at the thought that they might turn out to be lean, hardened men like Sharpe who might chop him out of his saddle before he had the chance to be painted in oils as a conquering hero. Sir Henry was already afraid and he had yet to see a single enemy, but first he had to get a subtle revenge on this Rifleman who had baffled him.

‘Three rounds a minute?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And how do you teach men to fire three rounds a minute?’

Sharpe shrugged. ‘Patience, sir. Practice. One battle does a world of good.’

Simmerson scoffed at him. ‘Patience! Practice! They aren’t children, Sharpe. They’re drunkards and thieves! Gutter scourings!’ His voice was rising again. ‘Flog it into them, Sharpe, flog! It’s the only way! Give them a lesson they won’t forget. Isn’t that right?’

There was silence. Simmerson turned to Forrest. ‘Isn’t that right, Major?’

‘Yes, sir.’ Forrest’s answer lacked conviction. Simmerson turned to Sharpe. ‘Sharpe?’

‘It’s the last resort, sir.’

‘The last resort, sir.’ Simmerson mimicked Sharpe but secretly he was pleased. It was the answer he had wanted. ‘You’re soft, Sharpe! Could you teach men to fire three rounds a minute?’

Sharpe could feel the challenge in the air but there was no going back. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘Right!’ Simmerson rubbed his hands together. ‘This afternoon. Forrest?’

‘Sir?’

‘Give Mr Sharpe a company. The Light will do. Mr Sharpe will improve their shooting!’ Simmerson turned and bowed to Hogan with a heavy irony. ‘That is if Captain Hogan agrees to lend us Lieutenant Sharpe’s services.’

Hogan shrugged and looked at Sharpe. ‘Of course, sir.’

Simmerson smiled. ‘Excellent! So, Mr Sharpe, you’ll teach my Light Company to fire three shots a minute?’

Sharpe looked out of the window. It was a hot, dry day and there was no reason why a good man should not fire five shots a minute in this weather. It depended, of course, how bad the Light Company were at the moment. If they could only manage two shots a minute now then it was next to impossible to make them experts in one afternoon but trying would do no harm. He looked back to Simmerson. ‘I’ll try, sir.’

‘Oh you will, Mr Sharpe, you will. And you can tell them from me that if they fail then I’ll flog one out of every ten of them. Do you understand, Mr Sharpe? One out of every ten.’

Sharpe understood well enough. He had been tricked by Simmerson into what was probably an impossible job and the outcome would be that the Colonel would have his orgy of flogging and he, Sharpe, would be blamed. And if he succeeded? Then Simmerson could claim it was the threat of the flogging that had done the trick. He saw triumph in Simmerson’s small red eyes and he smiled at the Colonel. ‘I won’t tell them about the flogging, Colonel. You wouldn’t want them distracted, would you?’

Simmerson smiled back. ‘You use your own methods, Mr Sharpe. But I’ll leave the triangle where it is; I think I’m going to need it.’

Sharpe clapped his misshapen shako on to his head and gave the Colonel a salute of bone-cracking precision. ‘Don’t bother, sir. You won’t need a triangle. Good day, sir.’

Now make it happen, he thought.

CHAPTER THREE

‘I don’t bloody believe it, sir. Tell me it’s not true.’ Sergeant Patrick Harper shook his head as he stood with Sharpe and watched the South Essex Light Company fire two volleys to the orders of a Lieutenant. ‘Send this Battalion to Ireland, sir. We’d be a free country in two weeks! They couldn’t fight off a church choir!’

Sharpe gloomily agreed. It was not that the men did not know how to load and fire their muskets; it was simply that they did it with a painful slowness and a dedication to the drill book that was rigorously imposed by the Sergeants. There were officially twenty drill movements for the loading and firing of a musket, five of them alone applied to how the steel ramrod should be used to thrust ball and charge down the barrel and the Battalion’s insistence on doing it by the book meant that Sharpe had timed their two demonstration shots at more than thirty seconds each. He had three hours, at the most, to speed them up to twenty seconds a shot and he could understand Harper’s reaction to the task. The Sergeant was openly scornful.

‘God help us if we ever have to skirmish alongside this lot! The French will eat them for breakfast!’ He was right. The company was not even trained well enough to stand in the battle-line, let alone skirmish with the Light troops out in front of the enemy. Sharpe hushed Harper as a mounted Captain trotted across to them. It was Lennox, Captain of the Light Company, and he grinned down on Sharpe.

‘Terrifying, isn’t it?’

Sharpe was not sure how to reply. To agree might seem to be criticising the grizzled Scot who seemed friendly enough. Sharpe gave a non-committal answer and Lennox swung himself out of the saddle to stand beside him.

‘Don’t worry, Sharpe. I know how bad they are, but his Eminence insists on doing it this way. If he left it to me I’d have the bastards doing it properly but if we break one little regulation then it’s three hours’ drill with full packs.’ He looked quizzically at Sharpe. ‘You were at Assaye?’ Sharpe nodded and Lennox grinned again. ‘Aye, I remember you. You made a name for yourself that day. I was with the 78th.’

‘They made a name for themselves too.’

Lennox was pleased with the compliment. Sharpe remembered the Indian field and sight of the Highland Regiment marching in perfect order to assault the Mahratta lines. Great gaps were blown in the kilted ranks as they calmly marched into the artillery storm but the Scotsmen had done their job, slaughtered the gunners, and daringly reloaded in the face of a huge mass of enemy infantry that did not have the courage to counter-attack the seemingly invincible Regiment. Lennox shook his head.

‘I know what you’re thinking, Sharpe. What the devil am I doing here with this lot?’ He did not wait for an answer. ‘I’m an old man, I was retired, but the wife died, the half pay wasn’t stretching and they needed officers for Sir Henry bloody Simmerson. So here I am. Do you know Leroy?’

‘Leroy?’

‘Thomas Leroy. He’s a Captain here, too. He’s good. Forrest is a decent fellow. But the rest! Just because they put on a fancy uniform they think they’re warriors. Look at that one!’

He pointed to Christian Gibbons who was riding his black horse on to the field. ‘Lieutenant Gibbons?’ Sharpe asked.

‘You’ve met then?’ Lennox laughed. ‘I’ll say nothing about Mr Gibbons, then, except that he’s Simmerson’s nephew, he’s interested in nothing but women, and he’s an arrogant little bastard. Bloody English! Begging your pardon, Sharpe.’

Sharpe laughed. ‘We’re not all that bad.’ He watched as Gibbons walked his horse delicately to within a dozen paces and stopped. The Lieutenant stared superciliously at the two officers. So this, Sharpe thought, is Simmerson’s nephew? ‘Are we needed here, sir?’

Lennox shook his head. ‘No, Mr Gibbons, we are not. I’ll leave Knowles and Denny with Lieutenant Sharpe while he works his miracles.’ Gibbons touched his hat and spurred his horse away. Lennox watched him go. ‘Can’t do any wrong, that one. Apple of the Colonel’s bloodshot eye.’ He turned and waved at the company. ‘I’ll leave you Lieutenant Knowles and Ensign Denny, they’re both good lads but they’ve learned wrong from Simmerson. You’ve got a sprinkling of old soldiers, that’ll help, and good luck to you, Sharpe, you’ll need it!’ He grunted as he heaved himself into the saddle. ‘Welcome to the madhouse, Sharpe!’

Sharpe was left with the company, its junior officers, and the ranks of dumb faces that stared at him as though fearful of some new torment devised by their Colonel. He walked to the front of the company, watching the red faces that bulged over the constricting stocks and glistened with sweat in the relentless heat, and faced them. His own jacket was unbuttoned, shirt open, and he wore no hat. To the men of the South Essex he was like a visitor from another continent. ‘You’re in a war now. When you meet the French a lot of you are going to die. Most of you.’ They were appalled by his words. ‘I’ll tell you why.’

He pointed over the eastern horizon. ‘The French are over there, waiting for you.’ Some of the men looked that way as though they expected to see Bonaparte himself coming through the olive trees on the outskirts of Castelo Branco. ‘They’ve got muskets and they can all fire three or four shots a minute. Aimed at you. And they’re going to kill you because you’re so damned slow. If you don’t kill them first then they will kill you, it is as simple as that. You.’ He pointed to a man in the front rank. ‘Bring me your musket!’

At least he had their attention and some of them would understand the simple fact that the side which pumped out the most bullets stood the best chance of winning. He took the man’s musket, a handful of ammunition, and discarded his rifle. He held the musket over his head and went right back to the beginnings.

‘Look at it! One India Pattern musket. Fifty-five and a quarter inches long with a thirty-nine-inch barrel. It fires a ball three-quarters of an inch wide, nearly as wide as your thumb, and it kills Frenchmen!’ There was a nervous laugh but they were listening. ‘But you won’t kill any Frenchmen with it. You’re too slow! In the time it takes you to fire two shots the enemy will probably manage three. And, believe me, the French are slow. So, this afternoon, you will learn to fire three shots in a minute. In time you’ll fire four shots every minute and if you’re really good you should manage five!’

The company watched as he loaded the musket. It had been years since he had fired a smooth-bore musket but compared to the Baker rifle it was ridiculously easy. There were no grooves in the barrel to grip the bullet and no need to force the ramrod with brute force or even hammer it down. A musket was fast to load which was why most of the army used it instead of the slower, but much more accurate, rifle. He checked the flint, it was new and well seated in its jaws, so he primed and cocked the gun. ‘Lieutenant Knowles?’

A young Lieutenant snapped to attention. ‘Sir!’

‘Do you have a watch?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Can it time one minute?’

Knowles dragged out a huge gold hunter and snapped open the lid. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘When I fire you will keep an eye on that watch and tell me when one minute has passed. Understand?’

‘Yes, sir.’

He turned away from the company and pointed the musket down the field towards a stone wall. Oh God, he prayed, let it not misfire, and pulled the trigger. The swan neck with its gripped flint snapped forward, the powder in the pan flashed, and a fraction later the main charge exploded and he felt the heavy kick as the lead ball was punched out of the barrel in a gout of thick, white smoke.

Now it was all instinct; the never-forgotten motions. Right hand away from the trigger, let the gun fall in the left hand and as the butt hits the ground the right hand already has the next cartridge. Bite off the bullet. Pour the powder down the barrel but remember to keep a pinch for the priming. Spit in the ball. Ramrod out, up, and down the barrel. A quick push and then it’s out again, the gun is up, the cock back, priming in the pan, and fire into the lingering smoke of the first shot.

And again and again and again and memories of standing in the line with sweating, mad-eyed comrades and going through the motions as if in a nightmare. Ignoring the billows of smoke, the screams, edging left and right to fill up the gaps left by the dead, just loading and firing, loading and firing, letting the flames spit out into the fog of powder smoke, the lead balls to smash into the unseen enemy and hope they are falling back. Then the command to cease fire and you stop. Your face is black and stinging from the explosions of the powder in the pan just inches from your right cheek, your eyes smarting from the smoke and the powder grains, and the cloud drifts away leaving the dead and wounded in front and you lean on the musket and pray that the next time the gun would not hang-fire, snap a flint, or simply refuse to fire at all.

He pulled the trigger for the fifth time, the ball hammered away down the field, and the musket was down and the powder in the barrel before Knowles called ‘Time’s up!’

The men cheered, laughed and clapped because an officer had broken the rules and showed them he could do it. Harper was grinning broadly. He at least knew how difficult it was to make five shots in a minute and Sharpe knew that the Sergeant had noticed how he had cunningly loaded the first shot before the timed minute began. Sharpe stopped the noise. ‘That is how you will use a musket. Fast! Now you’re going to do it.’

There was silence. Sharpe felt the devilment in him; had not Simmerson told him to use his own method? ‘Take off your stocks!’ For a moment no one moved. The men stared at him. ‘Come on! Hurry! Take your stocks off!’

Knowles, Denny, and the Sergeants watched, puzzled, as the men gripped their muskets between their knees and used both hands to wrench apart the stiff leather collars.

‘Sergeants! Collect the stocks. Bring them here.’

The Battalion had been brutalised too much. There was no way he could teach them to be fast-shooting soldiers unless he offered them an opportunity to take their revenge on the system that had condemned them to a flogger’s Battalion. The Sergeants came to him, their faces dubious, their arms piled high with the hated stocks.

‘Put them down there.’ Sharpe made them heap the seventy-odd stocks about forty paces in front of the company. He pointed to the glistening heap. ‘That is your target! Each of you will be given just three rounds. Just three. And you will have one minute in which to fire them! Those who succeed, twice in a row, will drop out and have a lazy afternoon. The rest will go on trying and go on trying until they do succeed.’

He let the two officers organise the drill. The men were grinning broadly and there was a buzz of conversation in the ranks that he did not try to check. The Sergeants looked at him as though he were committing treason but none dared cross the tall, dark Rifleman with the long sword. When all was ready Sharpe gave the word and the bullets began smashing their way into the pile of leather. The men forgot their old drill and concentrated on shooting their hatred into the leather collars that had given them sore necks and which represented Simmerson and all his tyranny. At the end of the first two sessions only twenty men had succeeded, nearly all of them old soldiers who had re-enlisted in the new Battalion, but an hour and three-quarters later, as the sun reddened behind him, the last man fired his last shot into the fragments of stiff leather that littered the grass.

Sharpe lined the whole company in two ranks and watched, satisfied, as they shot three volleys to Harper’s commands. He looked through the white smoke that lingered in the still air towards the eastern horizon. Over there, in the Estramadura, the French were waiting, their Eagles gathering for the battle that had to come while behind him, in the lane that led from the town, Sir Henry Simmerson was in sight coming to claim his victory and his victims for the triangle.

‘For what we are about to receive,’ Harper said softly.

‘Quiet! Make them load. We’ll give the man a demonstration.’ Sharpe watched Simmerson’s eyes as the slow dawning of his men’s unbuttoned collars and the significance of the leather shreds on the grass occurred in his brain. Sharpe watched the Colonel take a deep breath. ‘Now!’

‘Fire!’ Harper’s command unleashed a full volley that echoed like thunder in the valley. If Simmerson shouted then his words were lost in the noise and the Colonel could only watch as his men worked their muskets like veterans to the orders of a Sergeant of the Rifles, even bigger than Sharpe, whose broad, confident face was of the kind that had always infuriated Sir Henry, provoking his most savage sentences from the uncushioned magistrates’ bench in Chelmsford.

The last volley rattled on to the stone wall and Forrest tucked his watch back into a pocket. ‘Two seconds under a minute, Sir Henry, and four shots.’

‘I can count, Forrest.’ Four shots? Simmerson was impressed because secretly he had despaired of teaching his men to fire fast instead of fumbling nervously. But a whole company’s stocks? At two and threepence a piece? And on a day when his nephew had come in smelling like a stable hand? ‘God damn your eyes, Sharpe!’

‘Yes, sir.’

The acrid powder smoke made Sir Henry’s horse twitch its head and the Colonel reached forward to quiet it. Sharpe watched the gesture and knew that he had made a fool of the Colonel in front of his own men and he knew, too, that it had been a mistake. Sharpe had won a small victory but in doing so he had made an enemy who had both power and influence. The Colonel edged his horse closer to Sharpe and his voice was surprisingly quiet. ‘This is my Battalion, Mr Sharpe. My Battalion. Remember that.’ He looked for a moment as if his anger would erupt but he controlled it and shouted at Forrest to follow him instead. Sharpe turned away. Harper was grinning at him, the men looked pleased, and only Sharpe felt a foreboding of menace like an unseen but encircling enemy. He shook it off. There were muskets to clean, rations to issue, and, beyond the border hills, enemies enough for anyone.

CHAPTER FOUR

Patrick Harper marched with a long easy stride, happy to feel the road beneath his feet, happy they had at last crossed the unmarked frontier and were going somewhere, anywhere. They had left in the small, dark hours so that the bulk of the march would be done before the sun was at its hottest and he looked forward to an afternoon of inactivity and hoped that the bivouac Major Forrest had ridden ahead to find would be near a stream where he could drift a line down the water with one of his maggots impaled on the hook. The South Essex were somewhere behind them; Sharpe had started the day’s march at the Rifle Regiment’s fast pace, three steps walking, three running, and Harper was glad that they were free of the suspicious atmosphere of the Battalion. He grinned as he remembered the stocks. There was a sobering rumour that the Colonel had ordered Sharpe to pay for every one of the seventy-nine ruined collars and that, to Harper’s mind, was a terrible price to pay. He had not asked Sharpe the truth of the rumour; if he had he would have been told to mind his own business, though, for Patrick Harper, Sharpe was his business. The Lieutenant might be moody, irritable, and liable to snap at the Sergeant as a means of venting frustration, but Harper, if pressed, would have described Sharpe as a friend. It was not a word that a Sergeant could use of an officer, but Harper could have thought of no other. Sharpe was the best soldier the Irishman had seen on a battlefield, with a countryman’s eye for ground and a hunter’s instinct for using it, but Sharpe looked for advice to only one man in a battle, Sergeant Harper. It was an easy relationship, of trust and respect, and Patrick Harper saw his business as keeping Richard Sharpe alive and amused.

He enjoyed being a soldier, even in the army of the nation that had taken his family’s land and trampled on their religion. He had been reared on the tales of the great Irish heroes, he could recite by heart the story of Cuchulain single-handedly defeating the forces of Connaught and who did the English have to put beside that great hero? But Ireland was Ireland and hunger drove men to strange places. If Harper had followed his heart he would be fighting against the English, not for them, but like so many of his countrymen he had found a refuge from poverty and persecution in the ranks of the enemy. He never forgot home. He carried in his head a picture of Donegal, a county of twisted rock and thin soil, of mountains, lakes, wide bogs and the smallholdings where families scratched a thin living. And what families! Harper was the fourth of his mother’s eleven children who survived infancy and she always said that she never knew how she had come to bear such ‘a big wee one’. ‘To feed Patrick is like feeding three of the others’ she would say and he would more often go hungry. Then came the day when he left to seek his own fortune. He had walked from the Blue Stack mountains to the walled streets of Derry and there got drunk, and found himself enlisted. Now, eight years later and twenty-four years old, he was a Sergeant. They would never believe that in Tangaveane!