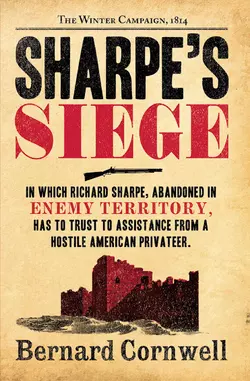

Sharpe’s Siege: The Winter Campaign, 1814

Bernard Cornwell

Richard Sharpe, abandoned in enemy territory, has to trust in assistance from a hostile American privateer.The invasion of France is under way, and the British Navy has called upon the services of Major Richard Sharpe. He and a small force of Riflemen are to capture a fortress and secure a landing on the French coast. It is to be one of the most dangerous missions of his career.Through the reckless incompetence of a naval commander, Sharpe finds himself abandoned in the heart of enemy territory, facing overwhelming forces and the very real prospect of defeat. He has no alternative but to trust his fortunes to an American privateer – a man who has no love for the British invaders.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.

SHARPE’S SIEGE

Richard Sharpe and the

Winter Campaign, 1814

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

This novel is a work of fiction. The incidents and some of the characters portrayed in it, while based on real historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Previously published in paperback by Fontana 1988

Reprinted five times

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1987

Copyright © Rifleman Productions Ltd 1987

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007298600

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007346813

Version: 2017-04-26

Sharpe’s Siege is dedicated to

Brenym McNight, Terry Farrand, Bryan Thorniley,

Diana Colbert, Ray Steele, and Stuart Wilkie;

with thanks

Contents

Title Page (#u920623ad-bfbc-5d29-b335-1920a4880e62)

Copyright (#u3b642d48-e501-57d9-acce-cce3477d4cc3)

Dedication (#uf37bfad4-7c46-5db5-8ea6-02f2bec22fc3)

Epigraph (#u0ec9d051-0fc3-5e77-a03e-59ccd3525e21)

Map of The French Biscay Coast (#u9790c2b6-8f10-5283-8c2e-ac062cd1c692)

Map of Bassin (#u28adcf45-8f13-51b9-b77a-c245360996bc)

Chapter One (#u3bc12159-dbd0-56d1-98c9-ce1e5355bebe)

Chapter Two (#u75fe86f6-1024-50d3-a691-10202b57234a)

Chapter Three (#u1731c2ae-f234-5688-b744-972d9db2e034)

Chapter Four (#ud131b3b7-9517-5662-acf1-51ba9f599def)

Chapter Five (#u7d7afc20-a9fe-5b82-9fe8-edd5d7981300)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Sharpe’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order) (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication) (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Bernard Cornwell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Cornwell has maintained a marvellously high standard throughout the series … brilliantly lucid and compellingly exciting’

Evening Standard

CHAPTER ONE

It was ten days short of Candlemas, 1814, and an Atlantic wind carried shivers of cold rain that slapped on narrow cobbled alleys, spilt from the broken gutters of tangled roofs, and pitted the water of St Jean de Luz’s inner harbour. It was a winter wind, cruel as a bared sabre, that whirled chimney smoke into the low January clouds shrouding the corner of south-western France where the British Army had its small lodgement.

A British soldier, his horse tired and mud-stained, rode down a cobbled street in St Jean de Luz. He ducked his head beneath a baker’s wooden sign, edged his mare past a fish-cart, and dismounted at a corner where an iron bollard provided a tethering post for the horse. He patted the horse, then slung its saddle-bags over his shoulder. It was evident he had ridden a long way.

He walked into a narrow alley, searching for a house that he only knew by description; a house with a blue door and a line of cracked green tiles above the lintel. He shivered. At his left hip there hung a long, metal-scabbarded sword, and on his right shoulder was a rifle. He stepped aside for a woman, black-dressed and squat, who carried a basket of lobsters. She, grateful that this enemy soldier had shown her a small courtesy, smiled her thanks, but afterwards, when she was safely past him, she crossed herself. The soldier’s face had been bleak and scarred; darkly handsome, but still a killer’s face. She blessed her patron saint that her own son would not have to face such a man in battle, but had a secure, safe job in the French Customs service instead.

The soldier, oblivious of the effect his face had, found the blue door beneath the green tiles. The door, even though it was a cold day, stood ajar and, without knocking, he pushed his way into the front room. There he dropped his pack, rifle, and saddle-bags on to a threadbare carpet and found himself staring into the testy face of a British Army surgeon. ‘I know you,’ the Army surgeon, his shirt-cuffs thick with dried blood, said.

‘Sharpe, sir, Prince of Wales’s Own …’

‘I said I knew you,’ the surgeon interrupted. ‘I took a musket-ball out of you after Fuentes d’Onoro. Had to truffle around for it, I remember.’

‘Indeed, sir.’ Sharpe could hardly forget. The surgeon had been half drunk, cursing, and digging into Sharpe’s flesh by the light of a guttering candle. Now the two men had met in the outer room of Lieutenant Colonel Michael Hogan’s lodgings.

‘You can’t go in there.’ The surgeon’s clothes were drenched in prophylactic vinegar, filling the small room with its acrid scent. ‘Unless you want to die.’

‘But …’

‘Not that I care.’ The surgeon wiped his bleeding-cup on the tail of his shirt then tossed it into his bag. ‘If you want the fever, Major, go inside.’ He spat on his wide-bladed scarifying gouge, smeared the blood from it, and shrugged as Sharpe opened the inner door.

Hogan’s room was heated by a huge fire that hissed where its flames met the rain coming down the chimney. Hogan himself was in a bed heaped with blankets. He shivered and sweated at the same time. His face was greyish, his skin slick with sweat, his eyes red-rimmed, and he was muttering about being purged with hyssop.

‘His topsails are gone to the wind,’ the surgeon spoke from behind Sharpe. ‘Feverish, you see. Did you have business with him?’

Sharpe stared at the sick man. ‘He’s my particular friend.’ He turned to look at the surgeon. ‘I’ve been on the Nive for the last month, I knew he was ill, but …’ He ran out of words.

‘Ah,’ the surgeon seemed to soften somewhat. ‘I wish I could offer some hope, Major.’

‘You can’t?’

‘He might last two days. He might last a week.’ The surgeon pulled on his jacket that he had shed before opening one of Hogan’s veins. ‘He’s wrapped in red flannel, bled regular, and we’re feeding him gunpowder and brandy. Can’t do more, Major, except pray for the Lord’s tender mercies.’

The sickroom stank of vomit. The heat of the huge fire pricked sweat on Sharpe’s face and steamed rain-water from his soaking uniform as he stepped closer to the bed, but it was obvious Hogan could not recognize him. The middle-aged Irishman, who was Wellington’s Chief of Intelligence, shivered and sweated and shook and muttered nonsenses in a voice that had so often amused Sharpe with its dry wit.

‘It’s possible,’ the surgeon spoke grudgingly from the outer room, ‘that the next convoy might bring some Jesuit’s bark.’

‘Jesuit’s bark?’ Sharpe turned towards the doorway.

‘A South American tree-bark, Major, sometimes called quinine. Infuse it well and it can perform miracles. But it’s a rare substance, Major, and cruelly expensive!’

Sharpe went closer to the bed. ‘Michael? Michael?’

Hogan said something in Gaelic. His eyes flickered past Sharpe, closed, then opened again.

‘Michael?’

‘Ducos,’ the sick man said distinctly, ‘Ducos.’

‘He’ll not make sense,’ the surgeon said.

‘He just did.’ Sharpe had heard a name, a French name, the name of an enemy, but in what feverish context and from what secret compartment of Hogan’s clever mind the name had come, Sharpe could not tell.

‘The Field Marshal sent me,’ the surgeon seemed eager to explain himself, ‘but I can’t work miracles, Major. Only the Almighty’s providence can do that.’

‘Or Jesuit’s bark.’

‘Which I haven’t seen in six months.’ The surgeon still stood at the door. ‘Might I insist you leave, Major? God spare us a contagion.’

‘Yes.’ Sharpe knew he would never forgive himself if he did not give Hogan some gesture of friendship, however useless, so he stooped and took the sick man’s hand and gave it a gentle squeeze.

‘Maquereau,’ Hogan said quite distinctly.

‘Maquereau?’

‘Major!’

Sharpe obeyed the surgeon’s voice. ‘Does maquereau mean anything to you?’

‘It’s a fish. The mackerel. It’s also French slang for pimp, Major. I told you, his wits are wandering.’ The surgeon closed the door on the sickroom. ‘And one other piece of advice, Major.’

‘Yes?’

‘If you want your wife to live, then tell her she must stop visiting Colonel Hogan.’

Sharpe paused by his damp luggage. ‘Jane visits him?’

‘A Mrs Sharpe visits daily,’ the doctor said, ‘but I have not the intimacy of her first name. Good day to you, Major.’

It was winter in France.

The floor was a polished expanse of boxwood, the walls were cliffs of shining marble, and the ceiling a riot of ornate plasterwork and paint. In the very centre of the floor, beneath the dark, cobweb encrusted chandelier and dwarfed by the huge proportions of the vast room, was a malachite table. Six candles, their light too feeble to reach into the corners of the great room, illuminated maps spread on the green stone table.

A man walked from the table to a fire that burned in an intricately carved hearth. He stared at the flames and, when at last he spoke, the marble walls made his voice seem hollow with despair. ‘There are no reserves.’

‘Calvet’s demi-brigade …’

‘Is ordered south without delay.’ The man turned from the fire to look at the table where the candle-glow illuminated two pale faces above dark uniforms. ‘The Emperor will not take it kindly if we …’

‘The Emperor,’ the smallest man at the table interrupted in a voice of surprising harshness, ‘rewards success.’

January rain spattered the tall, east-facing windows. The velvet curtains of this room had been pulled down twenty-one years before, trophies to a revolutionary mob that had stormed triumphant through the streets of Bordeaux, and there had never been the money nor the will to hang new curtains. The consequence, in winters like this, was a draught of malevolent force. The fire scarcely warmed the hearth, let alone the whole huge room, and the general standing before the feeble flames shivered. ‘East or north.’

It was a simple enough problem. The British had invaded a small corner of southern France, nothing but a toe-hold between the southern rivers and the Bay of Biscay, and these men expected the British to attack again. But would Field Marshal the Lord Wellington go east or north?

‘We know it’s north,’ the smallest man said. ‘Why else are they collecting boats?’

‘In that case, my dear Ducos,’ the general paced back towards the table, ‘is it to be a bridge, or a landing?’

The third man, a colonel, dropped a smoked cigar on to the floor and ground it beneath his toe. ‘Perhaps the American can tell us?’

‘The American,’ Pierre Ducos said scathingly, ‘is a flea on the rump of a lion. An adventurer. I use him because no Frenchman can do the task, but I expect small help of him.’

‘Then who can tell us?’ The general came into the aureole of light made by the candles. ‘Isn’t that your job, Ducos?’

It was rare for Major Pierre Ducos’ competency to be so challenged, yet France was assailed and Ducos was almost helpless. When, with the rest of the French Army, he had been ejected from Spain, Ducos had lost his best agents. Now, peering into his enemy’s mind, Ducos saw only a fog. ‘There is one man,’ he spoke softly.

‘Well?’

Ducos’ round, thick spectacle lenses flashed candlelight as he stared at the map. He would have to send a message through the enemy lines, and he risked losing his last agent in British uniform, but perhaps the risk was justified if it brought the French the news they so desperately needed. East, north, a bridge, or a landing? Pierre Ducos nodded. ‘I shall try.’

Which was why, three days later, a French lieutenant stepped gingerly across a frosted plank bridge that spanned a tributary of the Nive. He shouted cheerfully to warn the enemy sentries that he approached.

Two British redcoats, faces swathed in rags against the bitter cold, called for their own officer. The French lieutenant, seeing he was safe, grinned at the picquet. ‘Cold, yes?’

‘Bloody cold.’

‘For you.’ The French lieutenant gave the redcoats a cloth-wrapped bundle that contained a loaf of bread and a length of sausage, the usual gesture on occasions such as this, then greeted his British counterpart with a happy familiarity. ‘I’ve brought the calico for Captain Salmon.’ The Frenchman unbuckled his pack. ‘But I can’t find red silk in Bayonne. Can the colonel’s wife wait?’

‘She’ll have to.’ The British lieutenant paid silver for the calico and added a plug of dark tobacco as a reward for the Frenchman. ‘Can you buy coffee?’

‘There’s plenty. An American schooner slipped through your blockade.’ The Frenchman opened his cartouche. ‘I also have three letters.’ As usual the letters were unsealed as a token that they could be read. More than a few officers in the British Army had acquaintances, friends or relatives in the enemy ranks, and the opposing picquets had always acted as an unofficial postal system between the armies. The Frenchman refused a mug of British tea and promised to bring a four-pound sack of coffee, purchased in the market at Bayonne, the next day. ‘That’s if you’re still here tomorrow?’

‘We’ll be here.’

And thus, in a manner that was entirely normal and quite above suspicion, Pierre Ducos’ message was safely delivered.

‘Why ever shouldn’t I visit Michael? It’s eminently proper. After all, no one can expect a sick man to be ill-behaved.’

Sharpe entirely missed Jane’s pun. ‘I don’t want you catching the fever. Give the food to his servant.’

‘I’ve visited Michael every day,’ Jane said, ‘and I’m in the most excellent health. Besides, you went to see him.’

‘I should imagine,’ Sharpe said, ‘that my constitution is more robust than yours.’

‘It’s certainly uglier,’ Jane said.

‘And I must insist,’ Sharpe said with ponderous dignity, ‘that you avoid contagion.’

‘I have every intention of avoiding it.’ Jane sat quite still as her new French maid put combs into her hair. ‘But Michael is our friend and I won’t see him neglected.’ She paused, as if to let her husband counter her argument, but Sharpe was quickly learning that in the great skirmish of marriage, happiness was bought by frequent retreats. Jane smiled. ‘And if I can endure this weather, then I must be quite as robust as any Rifleman.’ The sea-wind, howling off Biscay, rattled the casements of her lodgings. Across the roofs Sharpe could see the thicket of masts and spars made by the shipping crammed into the inner harbour. One of those ships had brought the new uniforms that were being issued to his men.

It was not before time. The veterans of the South Essex, that Sharpe now had to call the Prince of Wales’s Own Volunteers, had not been issued with new uniforms in three years. Their coats were ragged, faded, and patched, but now those old jackets, that had fought across Spain, were being discarded for new, bright cloth. Some French Battalion, seeing those new coats, would think of them as belonging to a fresh, unblooded unit and would doubtless pay dear for the mistake.

The orders to refit had given Sharpe this chance to be with his new wife, as it had given all the married men of the Battalion a chance to be with their wives. The Battalion had been stationed on the line of the River Nive, close to French patrols, and Sharpe had ordered the wives to stay in St Jean de Luz. These few days were thus made precious to Sharpe, days snatched from the frost-hard river-line, days to be with Jane, and days spoilt only by the illness that threatened Hogan’s life.

‘I take him food from the Club,’ Jane said.

‘The Club?’

‘Where we’re lunching, Richard.’ She turned from the mirror with the expression of a woman well pleased with her own reflection. ‘Your good jacket, I think.’

In every town that the British occupied, and in which they spent more than a few days, one building became a club for officers. The building was never officially chosen, nor designated as such, but by some strange process and within a day of two of the Army’s arrival, one particular house was generally agreed to be the place where elegant gentlemen could retire to read the London papers, drink mulled wine before a decently tended fire, or play a few hands of whist of an evening. In St Jean de Luz the chosen house faced the outer harbour.

Major Richard Sharpe, born in a common lodging-house and risen from the gutter-bred ranks of Britain’s Army, had never used such temporary gentlemen’s clubs before, but new and beautiful wives must be humoured. ‘I didn’t suppose,’ he spoke unhappily to Jane, ‘that women were allowed in gentlemens’ clubs?’ He was reluctantly buttoning his new green uniform jacket.

‘They are here,’ Jane said, ‘and they’re serving an oyster pie for luncheon.’ Which clinched the matter. Major and Mrs Richard Sharpe would dine out, and Major Sharpe had to dress in the stiff, uncomfortable uniform that he had bought for a royal reception in London and hated to wear. He reflected, as he climbed the wide stairs of the Officers’ Club with Jane on his arm, that there was much wisdom in the old advice that an officer should never take a well-bred wife to an ill-bred war.

Yet the frisson of irritation passed as he entered the crowded dining-room. Instead he felt the pang of pride that he always felt when he took Jane into a public place. She was undeniably beautiful, and her beauty was informed by a vivacity that gave her face character. She had eloped with him just months before, fleeing her uncle’s house on the drab Essex marshes to come to the war. She drew admiring glances from men at every table, while other officers’ wives, enduring the inconveniences of campaigning for the sake of love, looked enviously at Jane Sharpe’s easy beauty. Some, too, envied her the tall, black-haired and grimly scarred man who seemed so uncomfortable in the lavishness of the club’s indulgent comforts. Sharpe’s name was whispered from table to table; the name of the man who had taken an enemy standard, captured one of Badajoz’s foul breaches, and who, or so rumour said, had made himself rich from the blood-spattered plunder of Vitoria.

A white-gloved steward abandoned a table of senior officers to hasten to Jane’s side. ‘The cap’n wanted to sit ’ere, ma’am,’ the steward was unnecessarily brushing the seat of a chair close to one of the wide windows, ‘but I said as how it was being kept for someone special.’

Jane gave the steward a smile that would have enslaved a misogynist. ‘How very kind of you, Smithers.’

‘So he’s over there.’ Smithers nodded disparagingly towards a table by the fire where two naval officers sat in warm discomfort. The junior officer was a lieutenant, while one of the other man’s two epaulettes was bright and new, denoting a recent promotion to the rank of a full post captain.

Smithers looked devotedly back to Jane. ‘I’ve reserved a bottle or two of that claret you liked.’

Sharpe, who had been ignored by the steward, pronounced the wine good and hoped he was right. The oyster pie was certainly good. Jane said she would deliver a portion to Hogan’s lodgings that same afternoon and Sharpe again insisted that she should not actually enter the sickroom, and he saw a flicker of annoyance cross Jane’s face. Her irritation was not caused by Sharpe’s words, but by the sudden proximity of the naval captain who had rudely come to stand immediately behind Sharpe’s chair in a place where he could overhear the conversation of Major and Mrs Sharpe’s reunion.

The naval officer had not come to eavesdrop, but rather to stare through the rain-smeared window. His interest was in a small flotilla of boats that had appeared around the northern headland. The boats were squat and small, none more than fifty feet long, but each had a vast press of sail that drove the score of craft in a fast gaggle towards the harbour entrance. They were escorted by a naval brig that, in the absence of enemies, had its gunports closed.

‘They’re chasse-marées,’ Jane said to her husband.

‘Chasse-marrys?’

‘Coastal luggers, Richard. They carry forty tons of cargo each.’ She smiled, pleased with her display of knowledge. ‘You forget I was raised on the coast. The smugglers in Dunkirk used chasse-marées. The Navy,’ Jane said loudly enough for the intrusive naval captain to hear, ‘could never catch them.’

But the naval captain was oblivious to Mrs Sharpe’s goad. He stared at the straggling fleet of chasse-marées that, emerging from a brief rain-squall, seemed to crab sideways to avoid a sand-bar that was marked by a broken line of dirty foam. ‘Ford! Ford!’

The naval lieutenant dabbed his lips with a napkin, snatched a swallow of wine, then hastened to his captain’s side. ‘Sir?’

The captain took a small spyglass from the tail pocket of his coat. ‘There’s a lively one there, Ford. Mark her!’

Sharpe wondered why naval officers should be so interested in French coastal craft, but Jane said the Navy had been collecting the chasse-marées for days. She had heard that the boats, with their French crews, were being hired with English coin, but for what purpose no one could tell.

The small fleet had come to within a quarter mile of the harbour, and, to facilitate their entry into the crowded inner roads, each ship was lowering its topsail. The naval brig had hove-to, sails shivering, but one of the French coasters, larger than the rest of its fellows, was still under the full set of its five sails. The water broke white at its stem and slid in bubbling, greying foam down the hull that was sleeker than those of the other, smaller vessels.

‘He thinks it’s a race, sir,’ the lieutenant said with happy vacuity above Sharpe’s shoulder.

‘A handy craft,’ the captain said grudgingly. ‘Too good for the Army. I think we might take her on to our strength.’

‘Aye aye, sir.’

The faster, larger lugger had broken clear of the pack. Its sails were a dirty grey, the colour of the winter sky, and its low hull was painted a dull pitch-black. Its flush deck, like all the chasse-marées’ decks, was an open sweep broken only by the three masts and the tiller by which two men stood. Fishing gear was heaped in ugly, lumpen disarray upon the deck’s planking.

The naval brig, seeing the large lugger race ahead, unleashed a string of bright flags. The captain snorted. ‘Bloody Frogs won’t understand that!’

Sharpe, offended by the naval officers’ unwanted proximity, had been seeking a cause to quarrel, and now found it in the captain’s swearing in front of Jane. He stood up. ‘Sir.’

The naval captain, with a deliberate slowness, turned pale, glaucous eyes on to the Army major. The captain was young, plump, and confident that he outranked Sharpe. They stared into each other’s eyes, and Sharpe felt a sudden certainty that he would hate this man. There was no reason for it, no justification, merely a physical distaste for the privileged, amused face that seemed so full of disdain for the black-haired Rifleman.

‘Well?’ The naval captain’s voice betrayed a gleeful anticipation of the imminent argument.

Jane defused the confrontation. ‘My husband, Captain, is sensitive to the language of fighting men.’

The captain, not certain whether he was being complimented or mocked, chose to accept the words as a tribute to his gallantry. He glanced at Sharpe, looking from the Rifleman’s face to the new, unfaded cloth of the green jacket. The newness of the uniform evidently suggested that Sharpe, despite the scar on his face, was fresh to the war. The captain smiled superciliously. ‘Doubtless, Major, your delicacy will be sore tested by French bullets.’

Jane, delighted at the opening, smiled very sweetly. ‘I’m sure Major Sharpe is grateful for your opinion, sir.’

That brought a satisfying reaction; a shudder of astonishment and fear on the annoying, plump face of the young naval officer. He took an involuntary step backwards, then, remembering the cause of the near quarrel, bowed to Jane. ‘My apologies, Mrs Sharpe, if I caused offence.’

‘No offence, Captain … ?’ Jane inflected the last word into a question.

The captain bowed again. ‘Bampfylde, ma’am. Captain Horace Bampfylde. And allow me to name my lieutenant, Ford.’

The introductions were accepted gracefully, as tokens of peace, and Sharpe, outflanked by effusive politeness, sat. ‘The man’s got no bloody manners,’ he growled loudly enough to be overheard by the two naval officers.

‘Perhaps he didn’t have your advantages in life?’ Jane suggested sweetly, but again the scene beyond the window distracted the naval men from the barbed comments.

‘Christ!’ Captain Bampfylde, careless of the risk of offending a dozen ladies in the dining-room, shouted the word. The outraged anger in his voice brought an immediate hush and fixed the attention of everyone in the room on the small, impertinent drama that was unfolding on the winter-cold sea.

The black-hulled lugger, instead of obeying the brig’s command to lower sails and proceed tamely into the harbour of St Jean de Luz, had changed her course. She had been sailing south, but now reached west to cut across the counter of the brig. Even Sharpe, no sailor, could see that the chasse-marée’s fore and aft rig made the boat into a handy, quick sailor.

It was not the course change that had provoked Bampfylde’s astonishment, but that the deck of the black-hulled lugger had suddenly sprouted men like dragon’s teeth maturing into warriors, and that, from the mizzen mast, a flag had been unfurled.

The flag was not the blue ensign of the Navy, nor the tricolour of France, nor even the white banner of the exiled French monarchy. They were the colours of Britain’s newest enemy; the Stars and Stripes of the United States of America.

‘A Jonathon!’ a voice said with disgust.

‘Fire, man!’ Bampfylde roared the order in the confines of the dining-room as though the brig’s skipper might hear him. Yet the brig, head to wind, was helpless. Men ran on its deck, and gunports lifted, but the American lugger was seething past the brig’s unarmed counter and Sharpe saw the dirty white blossom of gunsmoke as the small broadside was poured, at pistol-shot length, into the British ship.

Lieutenant Ford groaned. David was taking on Goliath and winning.

The sound of the American gunfire came over the windbroken water like a growl of thunder, then the lugger was spinning about, sails rippling as the American skipper let his speed carry him through the wind’s eye, until, taut on the opposite tack, he headed back past the brig’s counter towards the fleet of chasse-marées.

The brig, foresails at last catching the wind to lever her hull around, received a second mocking broadside. The American carried five guns on each flank, small guns, but their shot punctured the brig’s Bermudan cedar to spread death down the packed deck.

Two of the brig’s guns punched smoke into the cold wind, but the American had judged his action well and the brig dared fire no more for fear of hitting the chasse-marées into which, like a wolf let rip into a flock, the American sailed.

The hired coasters were unarmed. Each sea-worn boat, sails frayed, was crewed by four men who did not expect, beneath the protection of their enemy’s Navy, to face the gunfire of an ally.

The French civilian crews leaped into the cold water as the Americans, serving their guns with an efficiency that Sharpe could only admire even if he could not applaud, put ball after ball into the luggers’ hulls. The gunners aimed low, intending to shatter, sink, and panic.

Ships collided. One chasse-marée’s mainmast, its shrouds cut, splintered down to the water in a tangle of tarred cables and tumbling spars. One boat was settling in the churning sea, another, its rudder shot away, turned broadside to receive the numbing shock of another’s bow in its gunwales.

‘Fire!’ Captain Bampfylde roared again, this time not as an order, but in alarm. Flames were visible on a French boat, then another, and Sharpe guessed the Americans were using shells as grenades. Rigging flared like a lit fuse, two more boats collided, tangled, and the flames flickered across the gap. Then a merciful rain-squall swept out of Biscay to help douse the flames even as it helped hide the American boat.

‘They’ll not catch her,’ Lieutenant Ford said indignantly.

‘Damn his eyes!’ Bampfylde said.

The American had got clear away. She could outsail her square-rigged pursuers, and she did. The last Sharpe saw of the black-hulled ship was the flicker of her grey sails in the grey squall and the bright flash of her gaudy flag.

‘That’s Killick!’ The naval captain spoke with a fury made worse by impotence. ‘I’ll wager that’s Killick!’

The spectators, appalled by what they had seen, watched the chaos in the harbour approach. Two luggers were sinking, three were burning, and another four were inextricably tangled together. Of the remaining ten boats no less than half had grounded themselves on the harbour bar and were being pushed inexorably higher by the force of the wind-driven, flowing tide. A damned American, in a cockle boat, had danced scornful rings around the Royal Navy and, even worse, had done it within sight of the Army.

Captain Horace Bampfylde closed his spyglass and dropped it into his pocket. He looked down at Sharpe. ‘Mark that well,’ the captain said, ‘mark it very well! I shall look to you for retribution.’

‘Me?’ Sharpe said in astonishment.

But there was no answer, for the two naval officers had strode away leaving a puzzled Sharpe and a tangle of scorched wreckage that heaved on the sea’s grey surface and bobbed towards the land where an Army, on the verge of its enemy’s country, gathered itself for its next advance, but whether to north or east, or by bridge or by boat, no one in France yet knew.

CHAPTER TWO

He had a cutwater of a face; sharp, lined, savagely tanned; a dangerously handsome face framed by a tangled shock of gold-dark hair. It was battered, beaten by winds and seas and scarred by blades and scorched by powder-blasts, but still a handsome face; enough to make the girls look twice. It was just the kind of face to annoy Major Pierre Ducos who disliked such tall, confident, and handsome men.

‘Anything you can tell me,’ Ducos said with forced politeness, ‘would be of the utmost use.’

‘I can tell you,’ Cornelius Killick said, ‘that a British brig is burying its dead and that the bastards have got close to forty chasse-marées in the harbour.’

‘Close to?’ Ducos asked.

‘It’s difficult to make an accurate count when you’re firing cannon, Major.’ The American, careless of Ducos’ sinister power, leaned over the malachite table and lit a cigar from a candle’s flame. ‘Aren’t you going to thank me?’

Ducos’ voice was sour with undisguised irony. ‘The Empire is most grateful to you. Captain Killick.’

‘Grateful enough to fetch me some copper sheeting?’ Killick’s French was excellent. ‘That was our agreement.’

‘I shall order some sent to you. Your ship is at Gujan, correct?’

‘Correct.’

Ducos had no intention of ordering copper sheeting sent to the Bassin d’Arcachon, but the American had to be humoured. The presence of the privateer captain had been most fortuitous for Ducos, but what happened to the American now was of no importance to an embattled France.

Cornelius Killick was the master of the Thuella, a New England schooner of sleek, fast lines. She had been built for one purpose alone; to evade the British blockade and, under Killick’s captaincy, the Thuella had become a thorn in the Royal Navy’s self-esteem. Whether as a cargo ship that evaded British patrols, or as a privateer that snapped up stragglers from British convoys, the schooner had led a charmed life until, at the beginning of January, as the Thuella stole from the mouth of the Gironde in a dawn mist, a British frigate had come from the silvered north and its bow-chasers had thumped nine-pounder balls into the Thuella’s transom.

The schooner, carrying a cargo of French twelve-pounder guns for the American Army, turned south. Her armament was no match for a frigate, nor could her speed save her in the light, mist-haunted airs. For three hours she was pounded. Shot after shot crashed into the stern and Killick knew that the British gunners were firing low to spring his planks and sink his beloved ship. But the Thuella had not sunk, and the mist was stirred by catspaws of wind, and the wind became a breeze and, even though damaged, the schooner had outrun her pursuer and taken refuge in the vast Bassin d’Arcachon. There, safe behind the guns of the Teste de Buch fort, the Thuella was beached for repairs.

The wounded Thuella needed copper, oak, and pitch. Day followed day and the supplies were promised, but never came. The American consul in Bordeaux pleaded on Cornelius Killick’s behalf, and the only answer had been the strange request, from Major Pierre Ducos, that the American take a chasse-marée south and investigate why the British collected such craft in St Jean de Luz. There was no French Navy to make the reconnaissance, and no French civilian crew, lured by British gold, could be trusted with the task, and so Killick had gone. Now, as he had promised, he had come to this lavish room in Bordeaux to give his report.

‘Would you have any opinion,’ Ducos now asked the tall American, ‘why the British are hiring chasse-marées?’

‘Perhaps they want a regatta?’ Killick laughed, saw that this Frenchman had no sense of humour at all, and sighed instead. ‘They plan to land on your coast, presumably.’

‘Or build a bridge?’

‘Where to? America? They’re filling the damned harbour with boats.’ Killick drew on his cigar. ‘And if they were going to make a bridge, Major, wouldn’t they take down the masts? Besides, where could they build it?’

Ducos unrolled a map and tapped the estuary of the Adour. ‘There?’

Cornelius Killick hid his impatience, remembering that the French had never understood the sea, which was why the British fleets now sailed with such impunity. ‘That estuary,’ the American said mildly, ‘has a tidefall of over fifteen feet, with currents as foul as rat-puke. If the British build a bridge there, Major, they’ll drown an army.’

Ducos supposed the American was right, but the Frenchman disliked being lectured by a ruffian from the New World. Major Ducos would have preferred confirmation from his own sources, but no reply had come to the letter that had been smuggled across the lines to the agent who served France in a British uniform. Ducos feared for that man’s safety, but the Frenchman’s pinched, scholarly face betrayed none of his worries as he interrogated the handsome American. ‘How many men,’ Ducos asked, ‘could a chasse-marée carry?’

‘A hundred. Perhaps more if the seas were calm.’

‘And they have forty. Enough for four thousand men.’ Ducos stared at the map on his table. ‘So where will they come, Captain?’

The American leaned over the table. Rain tapped on the window and a draught lifted a corner of the map that Killick weighted down with a candlestick. ‘The Adour, Arcachon, or the Gironde.’ He tapped each place as he spoke its name.

The map showed the Biscay coast of France. That coast was a sheer sweep, almost ruler straight, suggesting long beaches of wicked, tumbling surf. Yet the coast was broken by two river mouths and by the vast, almost landlocked Bassin d’Arcachon. And from Arcachon to Bordeaux, Ducos saw, it was a short march, and if the British could take Bordeaux they would cut off Marshal Soult’s army in the south. It was a bold idea, a risky idea, but on a map, in an office in winter, it seemed to Ducos a very feasible one. He moved the candle away and rolled the map into a tight tube. ‘You would be well advised, Captain Killick, to be many leagues from Arcachon if the British do make a landing there.’

‘Then send me some copper.’

‘It will be dispatched in the morning,’ Ducos said. ‘Good day to you, Captain, and my thanks.’

When the American was gone Ducos unrolled the map again. The questions still nagged at him. Was the display in St Jean de Luz’s harbour merely a charade to draw attention away from the east? Ducos cursed the man who had not replied to his letter, and wondered how much credence could be put on the words of an American adventurer. North or east, bridge or boats? Ducos was tempted to believe the American, but knowing an invasion was planned was useless unless the landing place was known. Yet one man might still tell him, and to know the answer would bring a victory, and France, in this bitter, wet winter of 1814, was in need of a victory.

‘Looking for us, sir?’ A midshipman in a tarred jacket stood at the top of weed-slimed watersteps on St Jean de Luz’s quay.

‘Are you the Vengeance?’ Sharpe looked apprehensively at the tiny boat, frail on the filth-littered water, that was to carry him to the Vengeance. Sharpe had received a sudden order, peremptory and harsh, that offered no explanations but merely demanded his immediate presence on the quay where a boat from His Majesty’s ship Vengeance would be waiting.

Four grinning oarsmen, doubtless hoping to see the Rifle officer slip on the steep stone stairs, waited in the gig. ‘The captain would have sent his barge, sir,’ the midshipman said in unconvincing apology, ‘but it’s being used for the other gentlemen.’

Sharpe stepped into the rocking gig. ‘What other gentlemen?’

‘No one confides in me, sir.’ The midshipman could scarce have been more than fourteen, but he gave his orders with a jaunty confidence as Major Sharpe crouched on the stern thwart and wondered which of the ships moored in the outer harbour was the Vengeance.

It seemed to be none of them, for the midshipman took his tiny craft out through the harbour entrance to buck and thump its bows in the tide-race over the sandbar. Ahead now, in the outer roads, a flotilla of naval craft was anchored. Amongst them, and towering over the other vessels like a behemoth, was a ship of the line. ‘Is that the Vengeance?’ Sharpe asked.

‘It is, sir. A 74, and as sweet a sailor as ever was.’

The midshipman’s enthusiasm seemed misplaced to Sharpe. Nothing about the Vengeance suggested sweetness; instead, moored in the long swell of the grey ocean, she seemed like a brutal mass of timber, rope and iron; one of the slab-sided killers of Britain’s deep-water fleet. Her chequered sides were like cliffs, and the ponderous hull, as Sharpe’s gig neared the vast craft, gave off the rotten stench of tar, unwashed bodies and ordure; the normal odour of a battleship becalmed.

The midshipman shouted orders, oars backed, the tiller was thrown across, and somehow the gig was laid alongside with scarce a bump of timber. Above Sharpe now, water dripping from its lower rungs, was a tumblehome ladder leading to the maindeck. ‘You’d like a sling lowered, sir?’ the midshipman asked solicitously.

‘I’ll manage.’ Sharpe waited as a wave lifted the gig, then jumped for the rain-slicked ladder. He clawed at it, held on, then scrambled ignominiously up to the greeting of a bosun’s whistle.

‘Major Sharpe! Welcome aboard.’

Sharpe saw an eager, ingratiating lieutenant who clearly expected to be recognized. Sharpe frowned. ‘You were with …’

‘With Captain Bampfylde, indeed, sir. I’m Ford.’

The elegantly clothed Ford made inconsequential conversation as he steered Sharpe towards the stern cabins. It was an honour, he said, to have such a distinguished soldier aboard, and was it possible that Sharpe was related to Sir Roderick Sharpe of Northamptonshire?

‘No,’ Sharpe was remembering Captain Bampfylde’s parting words in the Officer’s Club. Were those the reason for his summons here?

‘One of the Wiltshire Sharpes, perhaps?’ Ford seemed eager to place the Rifleman in a comforting social context.

‘Middlesex,’ Sharpe said.

‘Do mind your head,’ Ford smiled as he waved Sharpe under the break of the poopdeck. ‘I can’t quite place the Middlesex Sharpes.’

‘My mother was a whore, I was born in a common lodging-house, and I joined the Army as a private. Does that make it easier?’

Ford’s smile did not falter. ‘Captain Bampfylde’s waiting for you, sir. Please go in.’

Sharpe ducked under the lintel of the opened doorway to find himself in a lavishly furnished cabin that extended the width of the Vengeance’s wide stern. A dozen officers, their wine glasses catching the light from the galleried windows, sat around a polished dining table.

‘Major! We meet in happier circumstances.’ Captain Horace Bampfylde greeted Sharpe with effusive and false pleasure. ‘No damned American to spoil our conversation, eh? Come and meet the company.’

Seeing Bampfylde in his ship made Sharpe realize how very young the naval captain was. Bampfylde must still lack two years of thirty, yet the naval captain possessed an ebullient confidence and a natural authority to compensate for his lack of years. He had a fleshy face, quick eyes, and an impatient manner that he tried to disguise as he made the introductions.

Most of the men about the table were naval officers whose names meant nothing to Sharpe, but there were also two Army officers, one of whom Sharpe recognized. ‘Colonel Elphinstone?’

Elphinstone, a big, burly Engineer whose hands were calloused and scarred, beamed a welcome. ‘You haven’t met my brother-in-arms, Sharpe; Colonel Wigram.’

Wigram was a grey-faced, dour, bloodless creature who acknowledged the ironic introduction with a curt nod. ‘If you could seat yourself, Major Sharpe, we might at last begin.’ He managed to convey that Sharpe had delayed this meeting.

Sharpe sat beside Elphinstone in a chair close to the windows that looked on to the big, grey Atlantic swells that scarcely moved the Vengeance’s ponderous hull. He sensed an awkwardness in the cabin, and he judged that there was disagreement between Wigram and Elphinstone, a judgment that was confirmed when the tall Engineer leaned towards him. ‘It’s all bloody madness, Sharpe. Marines have got the pox so they want you instead.’

The comment, ostensibly made in a confiding voice, had easily carried to the far end of the table where Bampfylde sat. The naval captain frowned. ‘Our Marines have a contagious fever, Elphinstone; not the pox.’

Elphinstone snorted derision, while Colonel Wigram, on Sharpe’s left, opened a leather-bound notebook. The middle-aged Wigram had the manner of a man whose life had been spent in an office; as though all his impetuosity and enjoyment had been drained by dusty, dry files. His voice was precise and fussy.

Yet even Wigram’s desiccated voice could not drain the excitement from the proposals he brought to this council of war. One hundred miles to the north, and far behind enemy lines, was a fortress called the Teste de Buch. The fortress guarded the entrance to a natural harbour, the Bassin d’Arcachon, which was just twenty-five miles from the city of Bordeaux.

Elphinstone, at the mention of Bordeaux, gave a scornful grunt that was ignored by the rest of the cabin.

The fortress of Teste de Buch, Wigram continued, was to be captured by a combined naval and Army force. The expedition’s naval commander would be Captain Bampfylde, while the senior Army officer would be Major Sharpe. Sharpe, understanding that the chill, pedantic Wigram would not be travelling north, felt a pang of relief.

Wigram gave Sharpe a cold, pale glance. ‘Once the fortress is secured, Major, you will march inland to ambush the high road of France. A successful ambush will alarm Marshal Soult, and might even detach French troops to guard against further such attacks.’ Wigram paused. It seemed to Sharpe, listening to the slap of water at the Vengeance’s stern, that there was an unnatural strain in the cabin, as though Wigram approached a subject that had been discussed and argued before Sharpe arrived.

‘It is to be hoped,’ Wigram turned a page of his notebook, ‘that any prisoners you take in the ambush will provide confirmation of reports reaching us from the city of Bordeaux.’

‘Balderdash,’ Elphinstone said loudly.

‘Your dissent is already noted,’ Wigram said dismissively.

‘Reports!’ Elphinstone sneered the word. ‘Children’s tales, rumours, balderdash!’

Sharpe, uncomfortably trapped between the two men, kept his voice very mild. ‘Reports, sir?’

Captain Bampfylde, evidently Wigram’s ally in the disagreement, chose to reply. ‘We hear, Sharpe, that the city of Bordeaux is ready to rebel against the Emperor. If it’s true, and we profoundly hope that it is, then we believe the city might rise in spontaneous revolt when they hear that His Majesty’s forces are merely a day’s march away.’

‘And if they do rise,’ Colonel Wigram took up the thread, ‘then we shall ship troops north to Arcachon and invade the city, thus cutting France in two.’

‘You note, Sharpe,’ Elphinstone was relishing this chance to stir more trouble, ‘that you, a mere major, are chosen to make the reconnaissance. Thus, if anything goes wrong, you will carry the blame.’

‘Major Sharpe will make his own decisions,’ Wigram said blandly, ‘after interrogating his prisoners.’

‘Meaning you won’t go to Bordeaux,’ Elphinstone said confidingly to Sharpe.

‘But you have been chosen, Major,’ Wigram’s pale eyes looked at Sharpe, ‘not because of your lowly rank, as Colonel Elphinstone believes, but because you are known as a gallant officer unafraid of bold decisions.’

‘In short,’ Elphinstone continued the war across the table, ‘because you will make an ideal scapegoat.’

The naval officers seemed embarrassed by the contretemps, all but for Bampfylde who had evidently relished the clash of colonels. Now the naval captain smiled. ‘You merely have to understand, Major, that your first task is to escalade the fortress. Perhaps, before we explore the subsequent operations, Colonel Wigram might care to tell us about the Teste de Buch’s defences?’

Wigram turned pages in his notebook. ‘Our latest intelligence demonstrates that the garrison can scarcely man four guns. The rest of its men have been marched north to bolster the Emperor’s Army. I doubt whether Major Sharpe will be much troubled by such a flimsy force.’

‘But four fortress guns,’ Elphinstone said harshly, ‘could slice a Battalion to mincemeat. I’ve seen it!’ Implying, evidently truthfully, that Wigram had not.

‘If we imagine disaster,’ Bampfylde said smoothly, ‘then we shall allow timidity to convince us into inaction.’ The comment implied cowardice to Elphinstone, but Bampfylde seemed oblivious of the offence he had given. Instead he unrolled a chart on to the table. ‘Weight the end of that, Sharpe! Now! There seems to me just one sensible way to proceed.’

He outlined his plan which was, indeed, the only sensible way to proceed. The naval flotilla, under Bampfylde’s command, would sail northwards and land troops on the coast south of the Point d’Arcachon. That land force, commanded by Sharpe, would proceed towards the fortress, a journey of some six hours, and make an escalade while the defenders were distracted by the incursion of a frigate into the mouth of the Arcachon channel. ‘The frigate’s bound to take some punishment,’ Bampfylde said equably, ‘but I’m sure Major Sharpe will overcome the gunners swiftly.’

The chart showed the great Basin of Arcachon with its narrow entrance channel, and marked the fortress of Teste de Buch on the eastern bank of that channel. A profile of the fort, as a landmark for mariners, was sketched on the chart, but the profile told Sharpe little about the stronghold’s defences. He looked at Elphinstone. ‘What do we know about the fort, sir?’

Elphinstone had been piqued by Bampfylde’s discourteous treatment and thus chose to use the technical language of his trade, doubtless hoping thereby to annoy the bumptious naval captain. ‘It’s an old fortification, Sharpe, a square-trace. You’ll face a glacis rising to ten feet, with an eight counterscarp into the outer ditch. A width of twenty and a scarp often. That’s revetted with granite, by the way, like the rest of the damned place. Climb the scarp and you’re on a counterguard. They’ll be peppering you by now and you’ve got a forty foot dash to the next counterscarp.’ The colonel was speaking with a grim relish, as if seeing the figures running and dropping through the enemy’s plunging fire. ‘That’s twelve feet, it’s flooded, and the enceinte height is twenty.’

‘The width of that last ditch?’ Sharpe was making notes.

‘Sixteen, near enough.’ Elphinstone shrugged. ‘We don’t think it’s flooded more than a foot or two.’ Even if the naval officers did not understand Elphinstone’s language, they could understand the import of what he was saying. The Teste de Buch might be an old fort, but it was a bastard; a killer.

‘Weapons, sir?’ Sharpe asked.

Elphinstone had no need to consult his notes. ‘They’ve got six thirty-six pounders in a semi-circular bastion that butts into the channel. The other guns are twenty-fours, wall mounted.’

Captain Horace Bampfylde had listened to the technical language and understood that a small point was being scored against him. Now he smiled. ‘We should be grateful it’s not a tenaille trace.’

Elphinstone frowned, realizing that Bampfylde had understood all that had been said. ‘Indeed.’

‘No lunettes?’ Bampfylde’s expression was seraphic. ‘Caponiers?’

Elphinstone’s frown deepened. ‘Citadels at the corners, but hardly more than guerites.’

Bampfylde looked to Sharpe. ‘Surprise and speed, Major! They can’t defend the complete enceinte, and the frigate will distract them!’ So much, it seemed, for the problems of capturing a fortress. The talk moved on to the proposed naval operations inside the Bassin d’Arcachon, where more chasse-marées awaited capture, but Sharpe, uninterested in that part of the discussion, let his thoughts drift.

He did not see Bampfylde’s plush, shining cabin, instead he imagined a rising grass slope, scythed smooth, called a glacis. Beyond the glacis was an eight foot drop into a granite faced, sheer-sided ditch twenty feet wide.

At the far side of the ditch his men would be faced with a ten foot climb that would lead to a gentle, inward-facing slope; the counterguard. The counterguard was like a broad target displayed to the marksman on the inner wall, the enceinte. Men would cross the counterguard, screaming and twisting as the balls thumped home, only to face a twelve foot drop into a flooded ditch that was sixteen feet wide.

By now the enemy would be dropping shells or even stones. A boulder, dropped from the twenty foot high inner wall, would crush a man’s skull like an eggshell, yet still the wall would have to be climbed with ladders if the men were to penetrate into the Teste de Buch. Given a month, and a train of siege artillery, Sharpe could have blasted a broad path through the whole trace of ditches and walls, but he did not have a month. He had a few moments only in which he must save a frigate from the terrible battering of the fort’s heavy guns.

‘Major?’ Abruptly the image of the twenty foot wall vanished to be replaced by Bampfylde’s quizzically mocking smile. ‘Major?’

‘Sir?’

‘We are talking, Major, of how many men would be needed to defend the captured fortress while we await reinforcements from the south?’

‘How long will the garrison have to hold?’ Sharpe asked.

Wigram chose to answer. ‘A few days at the most. If we do find that Bordeaux’s ripe for rebellion, then we can bring an Army corps north inside ten days.’

Sharpe shrugged. ‘Two hundred? Three? But you’d best use Marines, because I’ll need all of my Battalion if you want me to march inland.’

It was Sharpe’s first trenchant statement and it brought curious glances from the junior naval officers. They had all heard of Richard Sharpe and they watched his weather-darkened, scarred face with interest.

‘Your Battalion?’ Wigram’s voice was as dry as old paper.

‘A brigade would be preferable, sir.’

Elphinstone snorted with laughter, but Wigram’s expression did not change. ‘And what leads you to suppose, Major, that the Prince of Wales’s Own Volunteers are going to Arcachon?’

Sharpe had assumed it because he had been summoned, and because he was the de facto commander of the Battalion, but Colonel Wigram now disabused him brutally.

‘You are here, Major, because you are supernumerary to regimental requirements.’ Wigram’s voice, like his gaze, was pitiless. ‘Your regimental rank, Major, is that of captain. Captains, however ambitious, do not command Battalions. You should be apprised that a new commanding officer, of due seniority and competence, is being appointed to the Prince of Wales’s Own Volunteers.’

There was a horrid and embarrassed silence in the cabin. Every man there, except for the young Captain Bampfylde, knew the bitter pangs of promotion denied, and each man knew they were watching Sharpe’s hopes being broken on the wheel of the Army’s regulations. The assembled officers looked away from Sharpe’s evident hurt.

And Sharpe was hurt. He had rescued that Battalion. He had trained it, given it the Prince of Wales’s name, then led it to the winter victories in the Pyrenees. He had hoped, more than hoped, that his command of the Battalion would be made official, but the Army had decided otherwise. A new man would be appointed; indeed, Wigram said, the new commanding officer was daily expected on the next convoy from England.

The news, given so coldly and unsympathetically in the formal setting of the Vengeance’s cabin, cut Sharpe to the bone, but there was no protest he could make. He guessed that was why Wigram had chosen this moment to make the announcement. Sharpe felt numbed.

‘Naturally,’ Bampfylde leaned forward, ‘the glory attached to the capture of Bordeaux will more than compensate for this disappointment, Major.’

‘And you will rejoin your Battalion, as a major, when this duty is done,’ Wigram said, as though that was some consolation.

‘Though the war,’ Bampfylde smiled at Sharpe, ‘may well be over because of your efforts.’

Sharpe stirred himself from the bitter disappointment. ‘Single-handed efforts, sir? Your Marines are poxed, my Battalion can’t come, what am I supposed to do? Train cows to fight?’

Bampfylde’s face showed a flicker of a frown. ‘There will be Marines, Major. The Biscay Squadron will be combed for fit men.’

Sharpe, his belligerence released by Wigram’s news, stared at the young naval captain. ‘It’s a good thing, is it not, that the malady has not spread to your sailors, sir? You seemed to have a full ship’s company as I came aboard?’

Bampfylde stared like a basilisk at Sharpe. Colonel Elphinstone gave a quick, sour laugh, but Wigram slapped the table like a timid schoolmaster calling a rowdy class to order. ‘You will be given troops. Major, in numbers commensurate to your task.’

‘How many?’

‘Enough,’ Wigram said testily.

The question of Sharpe’s troops was dropped. Instead Bampfylde talked of a brig-sloop that had been sent to watch the fortress and to question any local fishermen who put to sea. The presence of the American privateer was discussed and Bampfylde smiled as he spoke of the punishment that would be fetched on Cornelius Killick. ‘We must regard that doomed American as a bonus for our efforts.’ Then the talk went to naval signals, far beyond Sharpe’s competence to understand, and again he wondered about that fortress. Even under-manned a fortress was a formidable thing, and no one in this wide cabin seemed interested in ensuring that he was given a proper force. At the same time, as the voices buzzed about him, he tried to assuage the deep pain of losing the command of his Battalion.

Sharpe knew the regulations disqualified him from commanding the Battalion, but there were other Battalions commanded by majors and the regulations seemed to be ignored for those men. But not for Sharpe. Another man was to be given the superb instrument of infantry that Sharpe had led through the winter’s battles and, once again, Sharpe was adrift and unwanted in the Army’s flotsam. He reflected, bitterly, that if he had been a Northamptonshire Sharpe, or a Wiltshire Sharpe, with an Honourable tag to his name and a park about his father’s house, then this would not have happened. Instead he was a Middlesex Sharpe, conceived in a whore’s transaction and whelped in a slum, and thus a fit whipping-boy for bores like Wigram.

Colonel Elphinstone, sensing that Sharpe was miles away again, kicked the Rifleman’s ankle and Sharpe recovered attentiveness in time to hear Bampfylde inviting the assembled officers to dine with him.

‘I fear I can’t.’ Sharpe did not want to stay in this cabin where his disappointment had shamed him in front of so many officers. It was a petty motive, pride-born, but a soldier without pride was a soldier doomed for defeat.

‘Major Sharpe,’ Bampfylde explained with ill-concealed scorn, ‘has taken a wife, so we must forgo his company.’

‘I haven’t taken a wife,’ Elphinstone said belligerently, ‘but I can’t dine either. Your servant, sir.’

The two men, Sharpe and Elphinstone, travelled back to St Jean de Luz in Bampfylde’s barge. Elphinstone, swathed in a vast black cloak, shook his head sadly. ‘Bloody madness, Sharpe. Utter bloody madness.’

It began to rain. Sharpe wished he was alone with his misery.

‘You’re disappointed, aren’t you?’ Elphinstone remarked.

‘Yes.’

‘Wigram’s a bastard,’ Elphinstone said savagely, ‘and you’re to take no bloody notice of him. You’re not going to Bordeaux. Those are orders.’

Sharpe, stirred from his self-pity by Elphinstone’s ferocious words, looked at the big Engineer. ‘So why are we taking the fort, sir?’

‘Because we need the chasse-marées, why else? Or were you dozing through that explanation?’

Sharpe nodded. ‘Yes, sir.’

The rain fell harder as Elphinstone explained that the whole Arcachon expedition had been planned simply to release the three dozen chasse-marées that were protected behind the fortress guns. ‘I need those boats, Sharpe, not to waltz into bloody Bordeaux, but to build a bloody bridge. But for Christ’s sake don’t tell anyone it’s a bridge. I’m telling you, because I won’t have you gallivanting off to Bordeaux, you understand me?’

‘Entirely, sir.’

‘Wigram thinks we want the boats for a landing, because that’s what the Peer wants everyone to think. But it’s going to be a bridge, Sharpe, a damned great bridge to astonish the bloody Frogs. But I can’t build the bloody bridge unless you capture the bloody fort and get me the boats. After that, enjoy yourself. Go and ambush the high road, then go back to Bampfylde and tell him the Frogs are still loyal to Boney. No rebellion, no farting about, no glory.’ Elphinstone stared gloomily at the water which was being pocked by the cold rain into a resemblance of dirty, heaving gunmetal. ‘It’s Wigram who’s got this bee in his bonnet about Bordeaux. The fool sits behind a bloody desk and believes every rumour he hears.’

‘Is it a rumour?’

‘Some precious Frenchman pinned his ear back.’ Elphinstone plucked his cloak even tighter as the barge struggled against the current sweeping about the sandbar. ‘Michael Hogan didn’t help. He’s a friend of yours, isn’t he?’

‘Yes, sir.’

Elphinstone sniffed. ‘Damned shame he’s ill. I can’t understand why he encouraged Wigram, but he did. But you’re to take no notice, Sharpe. The Peer expects you to take the fortress, let bloody Bampfylde extract the boats, then come back here.’

Sharpe stared at Elphinstone and received a nod of confirmation. So Wellington was not unaware of Wigram’s plans, but Wellington was putting his own man, Sharpe, into the operation. Was that, Sharpe wondered, the reason why he had lost his Battalion?

‘It wouldn’t matter,’ Elphinstone went on, ‘except that we need the bloody Navy to carry us there, and we can’t control them. Bampfylde thinks he’ll get an earldom out of Bordeaux, so stop the silly bugger dead. No rising, no rebellion, no hopes, no glory, and no bloody earldom.’

Sharpe smiled. ‘There’ll be no fortress unless I have decent troops, sir.’

‘You’ll get the best I can find,’ Elphinstone promised, ‘but not in such numbers that might tempt you to invade Bordeaux.’

‘Indeed, sir.’

The oarsmen were grunting with the effort of fighting the tide’s last ebb as the barge rounded the harbour’s northern mole. Sharpe understood well enough what was happening. A simple cutting out expedition, necessitating the capture of a coastal fort, was needed to release the chasse-marées, but ambitious officers, eager to make a name for themselves in the waning months of the war, wished to turn that mundane operation into a flight of fancy. Sharpe, who would make the reconnaissance inland, was ordered to blunt their hopes.

The steersman pointed the boat’s prow towards a flight of green-slimed steps. The white-painted barge, in smoother water now, cut swiftly towards the quay. The rain became tempestuous, slicking the quay’s stones darker and drumming on the top of Sharpe’s shako.

‘In oars!’ the steersman shouted.

The white bladed oars rose like wings and the craft coasted in a smooth curve to the foot of the steps. Sharpe looked up. The harbour wall, sheer and black and wet, reared above him like a cliff. ‘How high is that?’ he asked Elphinstone.

The Colonel squinted upwards. ‘Eighteen feet?’ Then Elphinstone saw the point of Sharpe’s question and shrugged. ‘Let’s hope Wigram’s right and they’ve stripped the Teste de Buch of defenders.’

Because if the fort’s enceinte was defended Sharpe would have no chance, none, and his men would die so that the naval officer could blame the Army for failure. That was a chilling thought for a winter’s dusk in which the rain slanted from a steel-grey sky to pursue Sharpe through the alleys to where his wife sewed up a rent in his old jacket; his battle-jacket, the green jacket that he would wear to a fortress wall that waited for him in Arcachon.

CHAPTER THREE

‘I suppose,’ Richard Sharpe said harshly, ‘that the Army couldn’t find any real soldiers?’

‘That’s about the cut of it,’ the Rifle captain replied. ‘Mind you, I suppose the Army couldn’t find any real commanding officers either?’

Sharpe laughed. Colonel Elphinstone had done his best, and that best was very good indeed for, if Sharpe could not take his own men into battle, then there was no unit he would rather lead than Captain William Frederickson’s men of the 60th Rifles. He took Frederickson’s hand. ‘I’m glad, William.’

‘We’re not unhappy ourselves.’ Frederickson was a man of villainous, even vile, appearance. His left eye was gone and the socket was covered by a mildewed patch. Most of his right ear had been torn away by a bullet while two of his front teeth were clumsy fakes. All the wounds had been taken on the battlefield.

Frederickson’s men, with clumsy and affectionate wit, called him ‘Sweet William’. The 60th, raised to fight against the Indian tribes in America, was still known as the Royal American Rifles, though half the Company were Germans, a quarter were Spaniards enrolled during the long war, and the rest were British except for a single, harsh-faced man who alone justified his regiment’s old name. Sharpe had fought alongside this Company two years before and, seeing the bitter face, the name came back to him. ‘That’s the American. Taylor, isn’t it?’

‘Yes.’ Frederickson and Sharpe stood far enough from the two paraded Companies so their voices could not be overheard by the men.

‘We might come up against some Jonathons,’ Sharpe said. ‘There’s some bugger called Killick skulking in Arcachon. Will it worry Taylor if he has to fight his countrymen?’

Frederickson shrugged. ‘Leave him to me, sir.’

Two Companies of the green-jacketed Riflemen had been given to Sharpe. Frederickson commanded one, a Lieutenant Minver the other, and together they numbered one hundred and twenty-three men. Not many, Sharpe thought, to assault a fortress on the French coast. He walked further along the quay with Frederickson, stopping by a fish cart that dripped bloody scales into a puddle. ‘Between you and me, William, it’s a mess.’

‘I thought it might be.’

‘We leave tomorrow to capture a fortress. It isn’t supposed to be heavily defended, but no one’s sure. After that, God knows what happens. There’s a madman who wants us to invade France, but between you and me we’re not.’

Frederickson grinned, then turned and looked at the two Companies of Riflemen. ‘We’re capturing a fort all by our little selves?’

‘The Navy says a few Marines might be well enough to help us.’

‘That’s very decent of them.’ Frederickson stared at the great bulk of the Vengeance. Barges, propelled by huge sweeps, were taking casks of water from the harbour to the huge ship.

‘You’ll draw extra ammunition,’ Sharpe said. ‘The First Division’s paying for it.’

‘I’ll rob the bastards blind,’ Frederickson said happily.

‘And tonight you’ll do me the honour of dining with Jane and myself?’

‘I’d like to meet her.’ Frederickson sounded guarded.

‘She’s wonderful.’ Sharpe said it warmly, and Frederickson, seeing his friend’s enthusiasm, hoped that a new wife had not sapped Sharpe’s appetite for the bloody business that lay ahead at Arcachon.

Commandant Henri Lassan thought he detected sleet in the dawn, but he could not be sure until he climbed to the western bastion and saw how the flakes settled briefly on the great cheeks of his guns before melting into cold rivulets of water. The guns were loaded, as they always were, but their muzzles and vent-holes were stoppered against the damp. ‘Good morning, Sergeant!’

‘Sir!’ The sergeant stamped his feet and slapped his hands against the cold.

Lassan’s orderly climbed the stone ramp with a tray of coffee-mugs. Lassan always brought the morning guard a mug of coffee each and the men appreciated the small gesture. The Commandant, they said, was a gentleman.

Children ran across the courtyard and women’s voices sounded from the kitchens. There should not be women in the fort, but Lassan had let the families of his gun crews take up the quarters vacated by the infantry who had gone to the northern battles. Lassan believed his men were less likely to desert if their families were inside the defences.

‘There she is, sir.’ The sergeant pointed through the sleeting rain.

Lassan looked over the narrow Arcachon channel where the tide raced across the shoals. Beyond the sandbanks the surging grey waves were torn by wind into a maelstrom of broken white water amidst which, beating southwards, was a little ship.

The ship was a British brig-sloop with two tall masts and a vast driver-sail at her stern. Her black and white banded hull hid, Lassan knew, eighteen guns. Her sails were reefed, but even so she seemed to plunge through the waves and Lassan saw how high the spray fountained from the brig’s stem. ‘Our enemies,’ he said mildly, ‘are having a disturbed breakfast.’

‘Yes, sir.’ The sergeant laughed.

Lassan cradled his coffee mug. There was something vulnerable about his face, a drawn and frightened look that made his men protective of him. They knew Commandant Lassan wished to become a priest when this war ended and they liked him for it, but they also knew that he would fight as a soldier until the last shot of the war had been fired. Now he stared at the British brig. ‘You saw her last night?’

‘At sundown, sir,’ the sergeant was certain. ‘And there were lights out there at night.’

‘He’s watching us, isn’t he?’ Lassan smiled. ‘He’s seeing what we’re made of.’

The sergeant slapped the gun as a reply.

Lassan turned to stare thoughtfully into the fort’s courtyard. A warning had come from Bordeaux that he was to prepare for a British attack, but Bordeaux had sent him no men to reinforce his shrunken garrison. Lassan could man his big guns, or he could protect the landward walls, but he could not do both. If the British landed troops, and sent warships into the channel, then Lassan would be trapped between the hammer and the anvil. He turned back to stare at the British brig. If Bordeaux was right, that inquisitive craft was making a reconnaissance, and Lassan must deceive the watchers. He must make them think the fort was so thinly defended that a landing by troops would be unnecessary.

Lieutenant Gerard came yawning from the green-painted door of the officers’ quarters. Lassan hailed him. ‘Lieutenant!’

‘Sir?’

‘No flag today! And no washing hung to dry on the barracks’ roof!’ Not that anyone was likely to dry washing in this weather.

Gerard, his blue jacket unbuttoned above his braces, frowned. ‘No flag, sir?’

‘You heard me, Lieutenant! And no men in the embrasures, you hear? Sentries in the citadels only.’

‘I hear you, sir.’

Lassan turned back to see the brig-sloop tack into the rain-sodden wind. He saw a shiver of sails, a spume of foam, and he imagined the cloaked officers, their braid tarnished by salt, staring at the grey, crouching fort through their spyglasses. He knew that such little ships, sent to spy on the French coast, often stopped the fishing boats that worked close inshore. Today then, and every day for the next week, only those fishermen whom Henri Lassan trusted would be allowed past the guns of the Teste de Buch. They would be encouraged to take English gold, and encouraged to drink a glass of dark rum in English cabins, and encouraged to sell lobsters to blue-coated Englishmen, and in return they would tell a plausible lie or two on behalf of Henri Lassan.

Then, with a roar from these great, passive guns that waited for employment, Henri Lassan would strike a blow for France.

He smiled, pleased with his notion, and went to breakfast.

Before dinner Sharpe faced a miserable and unhappy few moments. ‘The answer,’ he repeated, ‘is no.’

Regimental Sergeant Major Patrick Harper stood in the small parlour of Jane’s lodgings and twisted his wet shako in thick, strong fingers. ‘I talked with Mr d’Alembord, sir, so I did, and he said I could come. I mean we’re only sitting around like washer-women in a bloody drought, so we are.’

‘There’s a new colonel coming, Patrick. He needs his RSM.’

Harper frowned. ‘Needs his major, too.’

‘He can’t lose both of us.’ Sharpe did not have the power to deny the Prince of Wales’s Own Volunteers the services of this massive Irishman. ‘And if you come, Patrick, the new man will only appoint a new RSM. You wouldn’t want that.’

Harper frowned. ‘I’d rather be in a scrap if one’s going, sir, and Mr Frederickson wouldn’t take me amiss, nor would he.’

Sharpe could not be persuaded. ‘No.’

The huge man, four inches taller than Sharpe’s six feet, grinned. ‘I could take sick leave, sir, so I could.’

‘You have to be sick first.’

‘But I am!’ Harper pointed to his mouth. ‘I’ve got a toothache something desperate, sir. Here!’ He opened his mouth, jabbed with his finger, and Sharpe saw that Harper did indeed have a reddened and swollen upper gum.

‘Does it hurt?’

‘It’s dreadful, so it is!’ Harper, sensing a chink in Sharpe’s armour, became enthusiastic about his pain. ‘It’s more of a throb, sir. On and off, on and off, like a great drumbeat in your skull. Desperate, it is!’

‘Then see a surgeon tonight,’ Sharpe said unsympathetically, ‘and have it pulled. Then get back to Battalion where you belong.’

Harper’s face dropped. ‘Truly, sir? I can’t come?’

Sharpe sighed. ‘I’d rather have you along, RSM, than any dozen other men.’ That was true a thousand times over. Sharpe knew of no man he would rather fight beside, but it could not be at Arcachon. ‘I’m sorry, Patrick. Besides you’re a father now. You should take care.’ Harper’s Spanish wife, just a month before, had given birth to a son that had been christened Richard Patricio Augustine Harper. Sharpe had found the choice of Richard an embarrassment, but Jane had been delighted when Harper sought permission to use the name. ‘And I’m doing you a favour, RSM,’ Sharpe went on.

‘How would that be, sir?’

‘Because your son will still have a father in two weeks.’ Sharpe was seeing that black, sheer, wet wall and the image of it made his voice savage. Then he turned as the door opened. ‘My dear.’

Jane, beautiful in a blue silken dress, smiled delightedly at Harper. ‘Sergeant Major! How’s the baby?’

‘Just grand, ma’am!’ Harper had formed a firm alliance with Mrs Sharpe that seemed aimed at subverting Major Sharpe’s authority. ‘And Isabella thanks you for the linen.’

‘You’ve got toothache!’ Jane frowned with concern. ‘Your cheek’s swollen.’

Harper blushed. ‘It’s only a wee ache, ma’am, nothing at all!’

‘You must have oil of cloves! There’s some in the kitchen. Come along!’

The oil of cloves was discovered and Harper sent, disconsolate, into the night.

‘He can’t come,’ Sharpe said after dinner, when he and Jane walked back alone through the town.

‘Poor Patrick.’ Jane insisted on stopping at Hogan’s lodgings, but there was no news. She had visited earlier in the day and thought the sick man was looking better.

‘I wish you wouldn’t risk yourself,’ Sharpe said.

‘You’ve said so a dozen times, Richard, and I promise I heard you each time.’

They went to bed and, just four hours later, the landlady hammered on their door. It was pitch dark outside and bitterly cold inside the bedroom. Frost had etched patterns on the small windowpanes, patterns that were reluctant to melt even though Sharpe revived the fire in the tiny grate. The landlady had brought candles and hot water. Sharpe shaved, then pulled on his old and faded Rifleman’s uniform. It was the uniform in which he fought, stained with blood and torn by bullet and blade. He would not go into action in any other uniform.

He oiled his rifle’s lock. He always carried a long-arm into battle, even though it had been ten years since he had been made into an officer. He drew his Heavy Cavalry sword from its scabbard and tested the fore-edge. It seemed odd to be going to war from his wife’s bed, odder still not to be marching with his own men or with Harper, and that thought gave him a flicker of unrest for he was not used to fighting without Harper beside him.

‘Two weeks,’ he said. ‘I should be back in two weeks. Maybe less.’

‘It will seem like eternity,’ Jane said loyally, then, with an exaggerated shudder, she threw the bedclothes back and snatched up the clothes that Sharpe had hung to warm before the fire. Her small dog, grateful for the chance, leaped into the warm pit of the bed.

‘You don’t have to come,’ Sharpe said.

‘Of course I’ll come. It’s every woman’s duty to watch her husband sail to the wars.’ Jane shivered suddenly, then sneezed.

A half hour later they went into the fish-smelling lane and the wind was like a knife in their faces. Torches flared on the quayside where the Amelie rose on the incoming tide.

A dark line of men, weapons gleaming softly, filed aboard the merchantman that was to be Sharpe’s transport. The Amelie was no jewel of Britain’s trading fleet. She had begun life as a collier, taking coal from the Tyne to the smoke thick Thames, and her dark timbers still stank thickly of coal-dust.

Casks and crates and nets of supplies were slung on board in the pre-dawn darkness. Boxes of rifle ammunition were piled on the quayside and with them were barrels of vilely salted and freshly-killed beef. Twice baked bread was wrapped in canvas and boxed in resinous pine. There were casks of water for the voyage, spare flints for the fighting, and whetstones for the sword-bayonets. Rope ladders were coiled in the Amelie’s scuppers so that the Riflemen, reaching the beach where they must disembark, could scramble down to the longboats sent from the Vengeance.