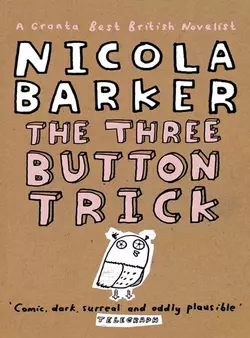

The Three Button Trick: Selected stories

Nicola Barker

The best short stories from perhaps England’s finest young female comic writer.This selection of Nicola Barker’s finest short stories contains work first published in ‘Heading Inland’ and ‘Love Your Enemies’.A sixteen-year-old girl, in ‘Layla’s Nose Job’, is burdened with a grotesque nose. But plastic surgery only serves to demonstrate that her strangeness isn’t just skin-deep. The discovery turns her ingeniously violent. In ‘Inside Information’, Martha, a professional shoplifter, becomes pregnant and attempts to turn her pregnancy to criminal advantage, only to find herself harassed by her foetus, which can not only talk but proves to have grisly plans of its own. In three related pieces (‘Blisters’, ‘Braces’, and ‘Mr. Lippy’) featuring Wesley, a charming but damaged young man, attempts at normality are grimly, inevitably defeated. In ‘The Three Button Trick’, one of Barker’s most naturalistic, a middle-aged woman, who’s been abandoned by her husband, discovers, thanks to the ministrations of several odd acquaintances, how little she needs him and how wayward and liberating true eroticism is.

NICOLA BARKER

The Three Button Trick

Contents

Cover (#u1f4096f8-e374-51e4-83b3-5da6289c724a)

Title Page (#u44f965ed-a712-5cbb-99aa-d4043b64c7b4)

The 3 Button Trick and Other Stories (#ua2bf7deb-4830-54a5-8eda-a7673984a162)

Layla’s Nose Job (#u22684a4a-3b2b-5712-8f79-7c3c5abb90fc)

Inside Information (#u07833111-2110-52ee-b44d-bb8f70deec0c)

The Butcher’s Apprentice (#u8c3013f3-c064-5ceb-b791-5b11d193f498)

G-String (#u257b7521-977f-5dd6-91ae-06259e2de46a)

The Three Button Trick (#ua928ddd4-8790-5298-93bf-44f4cd86283d)

Wesley: Blisters (#litres_trial_promo)

Wesley: Braces (#litres_trial_promo)

Wesley: Mr Lippy (#litres_trial_promo)

Skin (#litres_trial_promo)

Symbiosis: Class Cestoda (#litres_trial_promo)

The Piazza Barberini (#litres_trial_promo)

Popping Corn (#litres_trial_promo)

Dual Balls (#litres_trial_promo)

Water Marks (#litres_trial_promo)

Back to Front (#litres_trial_promo)

Limpets (#litres_trial_promo)

Bendy-Linda (#litres_trial_promo)

Gifts (#litres_trial_promo)

Parker Swells (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

THE 3 BUTTON TRICK and Other Stories (#ulink_b36cb271-e41a-57d5-8ef5-61934d98a5ac)

Layla’s Nose Job (#ulink_1ad08dc9-ab08-5193-903a-2a766ab381e7)

Layla Carter was just about as happy as it was possible for a sixteen-year-old North London girl to be who possessed a nose at least two centimetres longer than any nose among those of her contemporaries. As with all subjects of a sensitive nature, the length of Layla’s nose was an issue of great topicality and contention. Common clichés such as ‘Don’t be nosy’ or ‘You’re getting up my nose,’ even everyday phrases like ‘Who knows?’—especially when uttered by an errant younger brother with a meaningful glance at the relevant part of Layla’s physiognomy—would cause an atmosphere of hysterical teenage uproar in the Carter’s semi-detached in the leafy suburbs of Winchmore Hill.

Layla sensed that the source of her problem was genetic, but neither of her parents, Rose and Larry Carter, possessed noses of any note. Her three siblings were blessed with lovely, truffling pink snouts with snub ends and tiny nostrils. They had nothing to complain about.

Her nose had always been big. On family occasions like Christmas or Easter when her grandparents and great aunts descended on the Carter household for a roast lunch and a glass of Safeways own-brand port, the family photo albums would be dragged out of the cabinet under the television and all tied by blood and name would pore over them and sigh.

No one sighed louder than Layla. Her odyssey of agony and self-consciousness began with her christening snaps and continued well after the visitors had gone home, the washing-up had been done and the living-room carpet hoovered.

As far as she could tell, her nose had always been disproportionate. She had often had recourse to see other people’s christening photographs, and in none of them that she could remember had so many profile shots been taken to so much ill effect. Her nose emerged like a shark’s fin from between the delicate folds of her fine, pearly-white shawl, and the sight of it cut into her stomach like a blade.

She struggled to remember a time when the size of her nose hadn’t been a full-time preoccupation. As a young child in her first weeks at school, after a particularly violent spate of playground jousting—little boys shouting ‘big nose’ at her for a period in excess of fifteen minutes—her class teacher had bustled her, howling, into the staff-room and had dried her eyes, saying softly, ‘When you grow older you’ll study the Romans. They were the people who built all the best, long, straight roads in Britain, many, many years ago. Now just you guess what all of the Romans had in common? They all had fine aquiline noses. Long, straight, proud noses like yours. One day you’ll learn to be proud of your nose too. You’ll learn that all the best people have strong, bold, expressive faces and strong, proud, dignified noses.’ She offered Layla a tissue and said, ‘Now go on, blow.’ Layla pushed her face forward and then felt a pang of intense misery as her nose poked a hole through the centre of the tissue; like a dog jumping through a paper hoop. Nothing could console her.

People are so cruel, children are so cruel. In the school playground as she grew older, worse humiliations were in store. Her nose became her central signifier. Whenever her best friend Marcy was deputized to approach a handsome young buck for whom Layla had developed a girlish passion, she would always see him turn to Marcy with a frown and say, ‘Layla? Who’s she?’

By way of explanation Marcy would invariably point her out as she stood skulking in the corner of the playground closest to the girls’ toilets and say, ‘That’s her there. You know, the one with the big nose.’

Marcy always apologized for her indiscretions. She was a sympathetic girl, but she came from a big family where sensitivity and tact often had to be abandoned in the arena of attention-grabbing. She would say to Layla, ‘I’d much rather have a big nose than no nose at all.’

Neither of them had ever seen anyone without a nose before, but as the years dragged by Layla regularly stood in front of her bedroom mirror with her hand covering this offending part of her face in an attempt to perceive herself, and her other features, without its overwhelming presence. The result was often quite gratifying. Whenever she tried moaning to her mother, Rose would say, ‘Just be grateful for what you have got. You’ve got pretty blue eyes and lovely soft, brown, curly hair. You’ve got a good figure too. Be grateful. Try not to be so negative.’ In return, Layla would grimace and shout, ‘God! It’s bad enough having a nose like Mount Everest—I’d hardly tolerate being fat as well. I have to make the best of myself, but that doesn’t make things any better. In some ways that makes things worse. If I was truly ugly, what would I care if I had a big nose?’

She wished she could chop it off. When she was twelve, a short burst of appointments with the school therapist brought more light to this preoccupation. The therapist told Rose and Larry that Layla’s regular association in her conscious and unconscious mind with chopping and removal implied a rather unusual and boyish adherence to what is commonly called the castration complex. He said, ‘Layla wants to be a man. She wants to rival her father, Larry, for Rose’s love and attention. Unfortunately she has no penis. This makes the penis a hate object. She wants to castrate Larry’s penis because she is jealous of it. She feels guilty about her aggressive impulses towards Larry and so turns these feelings of violence on to herself. To Layla, her nose is a penis. Her hatred of her nose is symbolic of her hatred of her own sexuality. When she comes to terms with that, she’ll be a happier and more complete person.’

After their appointment the Carters took Layla for a hamburger at the McDonalds in Enfield’s town centre as a treat. She sipped her milkshake and frowned. She said, ‘What difference does all this make to me? Talking won’t change the size of my nose, will it? Why does everyone have to pretend that my nose isn’t the problem but that I am? It’s as if everyone who wants to help me is determined to believe that my nose isn’t all that big at all. But it is. It is!’

She had made her point. The family paid no heed to the therapist’s recommendations. Except Larry, who took to locking the bedroom and the bathroom doors whenever he happened to undress; especially when shaving. He must have felt guilty about something.

By the time that she was fifteen, Layla knew everything conceivable about dealing with an outsize nose. She knew how to react when boys got on to the school bus in the afternoons and laughed at her and gesticulated, she knew how to comb and style her hair in a way that helped to accentuate her better features as opposed to her worse, she knew how to avoid having her photograph taken on family occasions (on holiday and at home), she knew how to spend hours every morning with a make-up brush and facial foundation, shading the sides of her nose and lightening its centre in a way she’d seen depicted in hundreds of teenage girls’ magazines. Most of all she knew how to focus on this one, single thing. She made herself into a nose on legs.

She could not read a magazine without studying the nose of every model on its waxy, paper pages. If a model had a slightly larger nose than usual she would tear out the picture and put it into a scrapbook or stuff it in the drawer of her desk. At night she would list in her mind successful people who had big noses. She counted them like sheep in her pre-dream state; Chryssie Hynde, Margaret Thatcher, Barbra Streisand, Bette Midler, Dustin Hoffman, Rowan Atkinson, Cher. She thought about Cher quite a bit, because Cher had had her nose fixed.

In her dreams she visualized a scalpel, and its sharp edge touched her face like a kiss. It sliced her nose away so that her face felt light and radiant. But when she tried to bring her hand to her face to feel her new nose, her arms felt terribly heavy and could not be lifted. She used all her energy and willpower to attempt to lift them but they would not move. At this point she would awake from her dream and discover that she was actually trying to lift her arms, her real arms. In an instant she could then lift them to her face, and feel her face, and feel that everything was still the same. Even in her dreams, wish-fulfilment had its limits. Nothing ever went all the way.

Layla’s problems were more than just cosmetic when she was fifteen. At this time Marcy began going out with her first serious boyfriend. Although they remained best friends this meant that Marcy grew less supportive towards Layla and increasingly preoccupied with her new relationship. She also became enthusiastic about the idea of Layla becoming involved in a relationship herself. Layla had very high standards. All the boys who supposedly found her attractive did so (she firmly believed, with some grounds), because they were universally unattractive themselves.

But the pressure was on. Marcy visualized the ‘double date’ as the height of teenage sophistication and sociability. ‘Imagine how much fun we could have if you and someone else could come out with me and Craig,’ she’d say.

One warm summer Wednesday afternoon after school, Layla and Marcy went for a brisk stroll around the precinct in the town centre, looking at clothes, talking about teachers and drinking root beer. They ended up at Waitrose, where they bought a packet of Yum-Yum doughnut twists. Marcy suggested that they eat them on a bench in the park.

It was a set-up. Layla had barely taken the first bite of her doughnut when Craig turned up with one of his friends, Elvis. Her heart plummeted. After mumbling hello she walked a short distance to feed the rest of her Yum-Yum to a wayward duck. After a minute or so Marcy came over to her. She took her arm and said, ‘Don’t you like Elvis? Craig and I thought you’d get along.’

Layla baulked at this. She said, ‘You thought we’d get along because we both have big noses, is that it?’

Marcy laughed nervously. ‘Of course not. He’s Jewish. Lots of Jewish men have big noses, it’s natural.’

Layla forgot herself and wiped her sticky hands on her school dress. When she spoke again, her voice was dangerously calm. ‘Of all the boys in the school you choose the one with the biggest nose to match me up with. You’re supposed to be my best friend.’

‘Lots of women think that Jewish men are very sexy, that their big noses are sexy,’ Marcy interrupted.

Layla exploded, ‘I hate big noses. I hate my nose. Why the hell should I want to go out with someone with an enormous nose?’

The two boys had turned to face them from their position by the bench. Elvis looked flush and irritated. Craig was laughing. He called over, ‘You know what they say about men with big noses, don’t you, Layla? They’ve got the biggest pricks.’ He turned to Elvis. ‘You’ll vouch for that, won’t you?’

Elvis was extremely angry. He said, ‘You know what they say about girls with big noses, don’t you, Layla? They say that they’re very, very, very ugly, and that no one wants to go out with them.’ He showed her one finger.

Her face went crimson. Marcy tried to defuse the situation. She rubbed Layla’s arm apologetically. ‘He’s normally quite nice. I think he overheard us. He was upset, he didn’t mean what he said.’

Layla pulled her arm away with great violence, the force of which pushed her a step backwards and sent the duck skittering off. ‘Thanks a lot. Thanks for really humiliating me. I thought you were my friend. I suppose you and Craig had a real laugh planning this.’

Elvis had marched off in disgust, but Craig had made his way over to Marcy’s side and put his arm protectively around her shoulders. ‘Marcy was only trying to be nice. You make a mistake in thinking that everyone else is as interested in your stupid nose as you are. Elvis would’ve been a fool to want to go out with you, anyway. You’re too self-obsessed.’

Layla strode over to the bench where she had left her school bag, and picked it up by its strap. Then she turned and said, ‘Just because I have a big nose you all feel you’ve got the right to look down on me. I can just imagine Elvis and I going out on a date. Everyone who saw us would say, “Isn’t it nice that two such strangely deformed people have found each other.” I suppose it’s like two dwarves going out together or two blind people, or two people with terrible speech impediments who could spit and stutter at each other over Wimpy milkshakes. Well, I want better than that. I’m more than just a big nose. I thought I was your best friend, Marcy, but in fact I’m just your big-nosed friend. That’s all I am.’

Marcy said nothing as Layla sped away across the park.

That night when she got home Layla went straight to her bedroom. She locked the door and wouldn’t come out. Rose left her a dinner-tray outside the door. She was concerned for Layla. The previous week she had seen a programme on teenage suicide. Layla was so volatile. Larry told her not to worry.

Layla sat alone and did a lot of thinking. She tried to analyse her world view. She tried to get outside herself and to see her situation from all angles. One central problem faced her: had other people made her self-conscious about her nose, or was she just vain, as Craig had implied? Had she created the problem for herself, or had society made her nose into a monster? Obviously her nose had always been in the centre of her face and it had always been big, but was that in itself enough to destroy her life?

She thought about Elvis and wondered how much consideration he gave to the size of his nose. But his was a Jewish nose. Hers was just a big nose. She knew that the size of Elvis’s nose fitted into a larger scheme of things. It had a cultural space. It meant something. She thought, ‘If you’re Jewish and have a big nose it’s like being Barbra Streisand or Mel Brooks. It means that you have a history, that you belong. The shape of my nose is just a mistake. My problem is stuck right bang in the centre of my face, and it has no wider implications than that. My problem is my nose. I didn’t make the problem, the problem made me.’

It was so simple. It had to come off.

Late that evening she went downstairs into the living room and switched off the television. She stood in front of the screen—like a wonderful character from a film or a soap—and she announced firmly, ‘Either I have a nose job or I kill myself. I can’t go on like this any longer. I’ve heard that you can have one on the National Health. If you both love me you will help me.’ She swayed gently as though she were about to swoon, then gathered herself up and strode from the room like Boadicea approaching her chariot: a woman with swords on her wheels.

Rose made an appointment with their local GP the following afternoon. Layla took an hour off school. She explained her problem to the GP and he agreed to book her in with a specialist.

Five months later Layla met the specialist. He was called Dr Chris Shaben and was a small, vivacious, balding man with a crooked face and yellowy teeth. Apparently he had a very beautiful wife. His surgery was on Harley Street and the gold plaque on his door said, ‘Dr Chris Shaben, Plastic Surgeon’ in a beautiful flowing script.

Layla sat in his office and discussed her nose at great length. For the first time ever she felt as though she was actually talking to someone who cared, someone who understood, and best of all, someone who could do something. It was as a dream to her. Entering his surgery had been like a scene of recognition in a book or a film; that moment when everything falls into place. It was an ecstatic moment. Layla was like a newborn child finding its mother’s milky nipple for the first time.

It took a while to convince Dr Shaben that she was desperate and sincere. He said, ‘Normally we only do plastic surgery treatments on the National Health if the problem involved is more than just cosmetic, but I’m willing to make an exception in this instance, Layla. Although you’re young, you’re very articulate and intelligent. I realize that your concerns go deeper than mere vanity.’

Layla nodded. She said slowly, ‘For a while I tried to make myself believe that I had made the size of my nose into an issue, that the problem was to do with me, on the inside, not the out. My parents encouraged this line of thought, although my Mum has always been supportive, and my analysis did the same thing. But now I know that the problem is on the outside too. People judge one another visually; I should know, I do it myself. I want to be normal. I want to stop being on the outside, the periphery.’

Dr Shaben nodded and smiled at Layla. His bald head and short stature made him look like a tiny, benign, laughing Buddah as he sat hunched and serene in his big, leather, office chair.

Before the operation Layla abandoned her GCSE course work and concentrated instead on the leaflets, diagrams and information surrounding the surgery that she was about to undertake. She read how modern technology now meant that some nose operations could be undertaken entirely through the nostrils without any recourse to external incisions and unsightly scarring. The nose was chiefly made up out of bone and gristle, but was also extremely sensitive because of the large number of nerve endings at its tip. She tested this theory by smacking her nose with a pencil and then smacking other parts of her face like her cheeks and eyebrows. The nose was much more delicate. After the operation, a certain amount of swelling and bruising was to be expected.

Four days after her sixteenth birthday Layla awoke in a large and unfamiliar room. Her duvet was tightly stretched across her chest and felt unusually harsh and full of static. She was dopey. Her throat felt weird and dry. Her nose was numb but ached. She thought for an instant that she was dreaming her nose dream, that she wanted to put her hands to her face but her hands were restricted, yet after a few minutes she realized that she was in a strange bed in a strange environment. It was no dream, but her arms were restricted by the tightness of her sheets and blankets. She wriggled her body gently to create some room and worked her hands free. She placed them on her face. Her nose hurt. Her hands touched soft, filmy bandage and Band-Aid. It was done.

For the next five days her head felt light. Dr Shaben said that it was simply psychological, but she felt the lightness of a person who once had long hair and then cut it short, the roomy strangeness of someone who has had their arm broken and set in plaster and then has the plaster removed so that their arm floats up into the air because it feels so odd and weightless and light.

At first her face looked swollen and ugly. In hospital she wore no make-up and was blue with bruises. But she could see the difference. In the mirror her nose looked further away. Dr Shaben was pleased for her. He was well satisfied.

Throughout her stay in hospital, Rose had been in to see her every day. Larry preferred to stay away. Before she had gone in on her first night he had said to her, ‘Remember how when you were small I would sit you on my knee and bounce you up and down and call you my little elephant girl? You always laughed and giggled. It’s not like that any more. Now you’ve grown up into someone I don’t recognize. I can’t approve of what you are doing. God made you as you are. That should be enough.’

This came as a great shock to Layla. She had completely forgotten Larry’s pet name for her. When she heard him say it again it was like a blow to her face, a blow to her nose, making it ache, making her numb. It was a kind of violent anaesthetic.

She was being pulled in so many directions. Everyone had a different opinion as to the whys and wherefores. Rose simply said, ‘Do whatever will make you happy.’

After five days she came home. Although she was still slightly bruised, the mirror was her friend. Her three brothers greeted her at the front door with euphoric whoopings. Larry sat in the living room, watching the cricket. He turned after a minute or so and saw her, standing nervously by the door, her hands touching the bookcase for support. First he smiled, then he laughed, ‘Five days away, all that money spent, and look at you. No difference! You look no different.’ He laughed on long after she had left the room, but when he’d finished his stomach felt bitter.

Later Marcy visited. She smiled widely and hugged Layla like a real friend. Then she looked closely at her nose and said, ‘Maybe your nose looks slightly different, but to me you are still the same old Layla. In my mind’s eye you are exactly the same person. Nothing has changed.’ She thought that she was saying the right thing.

Layla sat alone upstairs in her room, staring into the mirror. She felt sure that she looked different. She felt sure that she was now a different person, inside. But the worry now consumed her that other people would not be able to see how different she looked. It felt like a conspiracy. She thought, ‘Maybe I’ve become the ugly person I was outside, inside. Perhaps that can never be changed.’ She felt like Pinocchio.

That night she had a dream. In her dream she was a tiny little elephant, but she was without a trunk. She had four legs and thick grey skin, but flapping ears and a thin end-tassled tail. But she had no nose. Because she had no nose she couldn’t pick things up—to eat, to wash, to have fun—all these things were now impossible. It was like being without arms. She kept asking for help. Her mother smiled and stroked her, but everyone else just laughed and pointed.

She slept late. When she awoke she felt battered and exhausted. When she looked into the mirror, her old face looked back at her. Nothing had changed. She felt utterly helpless. Her mind rambled and a thousand different images moved through the space behind her eyes. Her head was full of colour. She saw different people too, pointing their fingers, wiping her nose, holding her arm, bouncing her up and down on their knee, up and down, up and down.

In the kitchen she looked for a small knife to cut the top off her boiled egg. Instead she found that she had a chopping knife in her hand and it was as long as her arm. She cut the egg in half and its yolk hit the wall. She placed the blade near to her nose and felt tempted to move it closer. She stopped. For hours she remained stationary.

Larry had forgotten his sandwiches. He drove home in his lunch hour and let himself into the quiet house. He went upstairs for a quick pee. For once he neglected to shut and lock the door. He whistled contentedly.

Downstairs in the kitchen Layla’s mind started to turn again. She considered her options.

Inside Information (#ulink_f09452c1-af31-57ae-9d73-6394722d1486)

Martha’s social worker was under the impression that by getting herself pregnant, Martha was looking for an out from a life of crime.

She couldn’t have been more wrong.

‘First thing I ever nicked,’ Martha bragged, when her social worker was initially assigned to her, ‘very first thing I ever stole was a packet of Lil-lets. I told the store detective I took them as a kind of protest. You pay 17½ per cent VAT on every single box. Men don’t pay it on razors, you know, which is absolutely bloody typical.’

‘But you stole other things, too, on that occasion, Martha.’

‘Fags and a bottle of Scotch. So what?’ she grinned. ‘Pay VAT on those too, don’t you?’

Martha’s embryo was unhappy about its assignment to Martha. Early on, just after conception, it appealed to the higher body responsible for its selection and placement. This caused something of a scandal in the After-Life. The World-Soul was consulted—a democratic body of pin-pricks of light, an enormous institution—which came, unusually enough, to a rapid decision.

‘Tell the embryo,’ they said, ‘hard cheese.’

The embryo’s social worker relayed this information through a system of vibrations—a language which embryos alone in the Living World can produce and receive. Martha felt these conversations only as tiny spasms and contractions.

Being pregnant was good, Martha decided, because store detectives were much more sympathetic when she got caught. Increasingly, they let her off with a caution after she blamed her bad behaviour on dodgy hormones.

The embryo’s social worker reasoned with the embryo that all memories of the After-Life and feelings of uncertainty about placement were customarily eradicated during the trauma of birth. This was a useful expedient. ‘Naturally,’ he added, ‘the nine-month wait is always difficult, especially if you’ve drawn the short straw in allocation terms, but at least by the time you’ve battled your way through the cervix, you won’t remember a thing.’

The embryo replied, snappily, that it had never believed in the maxim that Ignorance is Bliss. But the social worker (a corgi in its previous incarnation) restated that the World Soul’s decision was final.

As a consequence, the embryo decided to take things into its own hands. It would communicate with Martha while it still had the chance and offer her, if not an incentive, at the very least a moral imperative.

Martha grew larger during a short stint in Wormwood Scrubs. She was seven months gone on her day of release. The embryo was now a well-formed foetus, and, if its penis was any indication, it was a boy. He calculated that he had, all things being well, eight weeks to change the course of Martha’s life.

You see, the foetus was special. He had an advantage over other, similarly situated, disadvantaged foetuses. This foetus had Inside Information.

In the After-Life, after his sixth or seventh incarnation, the foetus had worked for a short spate as a troubleshooter for a large pharmaceutical company. During the course of his work and research, he had stumbled across something so enormous, something so terrible about the World-Soul, that he’d been compelled to keep this information to himself, for fear of retribution.

The rapidity of his assignment as Martha’s future baby was, in part, he was convinced, an indication that the World-Soul was aware of his discoveries. His soul had been snatched and implanted in Martha’s belly before he’d even had a chance to discuss the matter rationally. In the womb, however, the foetus had plenty of time to analyse his predicament. It was a cover-up! He was being gagged, brainwashed and railroaded into another life sentence on earth.

In prison, Martha had been put on a sensible diet and was unable to partake of the fags and the sherry and the Jaffa cakes which were her normal dietary staples. The foetus took this opportunity to consume as many vital calories and nutrients as possible. He grew at a considerable rate, exercised his knees, his feet, his elbows, ballooned out Martha’s belly with nudges and pokes.

In his seventh month, on their return home, the foetus put his plan into action. He angled himself in Martha’s womb, at just the right angle, and with his foot, gave the area behind Martha’s belly button a hefty kick. On the outside, Martha’s belly was already a considerable size. Her stomach was about as round as it could be, and her navel, which usually stuck inwards, had popped outwards, like a nipple.

By kicking the inside of her navel at just the correct angle, the foetus—using his Inside Information—had successfully popped open the lid of Martha’s belly button like it was an old-fashioned pill-box.

Martha noticed that her belly button was ajar while she was taking a shower. She opened its lid and peered inside. She couldn’t have been more surprised. Under her belly button was a small, neat zipper, constructed out of delicate bones. She turned off the shower, grabbed hold of the zipper and pulled it. It unzipped vertically, from the middle of her belly to the top. Inside, she saw her foetus, floating in brine. ‘Hello,’ the foetus said. ‘Could I have a quick word with you, please?’

‘This is incredible!’ Martha exclaimed, closing the zipper and opening it again. The foetus put out a restraining hand. ‘If you’d just hang on a minute I could tell you how this was possible …’

‘It’s so weird!’ Martha said, dosing the zipper and getting dressed.

Martha went to Tesco’s. She picked up the first three items that came to hand, unzipped her stomach and popped them inside. On her way out, she set off the alarms—the bar-codes activated them, even from deep inside her—but when she was searched and scrutinized and interrogated, no evidence could be found of her hidden booty. Martha told the security staff that she’d consider legal action if they continued to harass her in this way.

When she got home, Martha unpacked her womb. The foetus, squashed into a corner, squeezed up against a tin of Spam and a packet of sponge fingers, was intensely irritated by what he took to be Martha’s unreasonable behaviour.

‘You’re not the only one who has a zip, you know,’ he said. ‘All pregnant women have them; it’s only a question of finding out how to use them, from the outside, gaining the knowledge. But the World-Soul has kept this information hidden since the days of Genesis, when it took Adam’s rib and reworked it into a zip with a pen-knife.’

‘Shut it,’ Martha said. ‘I don’t want to hear another peep from you until you’re born.’

‘But I’m trusting you,’ the foetus yelled, ‘with this information. It’s my salvation!’

She zipped up.

Martha went shopping again. She shopped sloppily at first, indiscriminately, in newsagents, clothes shops, hardware stores, chemists. She picked up what she could and concealed it in her belly.

The foetus grew disillusioned. He re-opened negotiations with his social worker. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘I know something about the World-Soul which I’m willing to divulge to my earth-parent Martha if you don’t abort me straight away.’

‘You’re too big now,’ the social worker said, fingering his letter of acceptance to the Rotary Club which preambled World-Soul membership. ‘And anyway, it strikes me that Martha isn’t much interested in what you have to say.’

‘Do you honestly believe,’ the foetus asked, ‘that any woman on earth in her right mind would consider a natural birth if she knew that she could simply unzip?’

The social worker replied coldly: ‘Women are not kangaroos, you cheeky little foetus. If the World Soul has chosen to keep the zipper quiet then it will have had the best of reasons for doing so.’

‘But if babies were unzipped and taken out when they’re ready,’ the foetus continued, ‘then there would be no trauma, no memory loss. Fear of death would be a thing of the past. We could eradicate the misconception of a Vengeful God.’

‘And all the world would go to hell,’ the social worker said.

‘How can you say that?’

The foetus waited for a reply, but none came.

Martha eventually sorted out her priorities. She shopped in Harrods and Selfridges and Liberty’s. She became adept at slotting things of all conceivable shapes and sizes into her belly. Unfortunately, the foetus himself was growing quite large. After being unable to fit in a spice rack, Martha unzipped and addressed him directly. ‘Is there any possibility,’ she asked, ‘that I might be able to take you out prematurely so that there’d be more room in there?’

The foetus stared back smugly. ‘I’ll come out,’ he said firmly, ‘when I’m good and ready.’

Before she could zip up, he added, ‘And when I do come out, I’m going to give you the longest and most painful labour in Real-Life history. I’m going to come out sideways, doing the can-can.’

Martha’s hand paused, momentarily, above the zipper. ‘Promise to come out very quickly,’ she said, ‘and I’ll nick you some baby clothes.’

The foetus snorted in a derisory fashion. ‘Revolutionaries,’ he said, ‘don’t wear baby clothes. Steal me a gun, though, and I’ll fire it through your spleen.’

Martha zipped up quickly, shocked at this vindictive little bundle of vituperation she was unfortunate enough to be carrying. She smoked an entire packet of Marlboro in one sitting, and smirked, when she unzipped, just slightly, at the coughing which emerged.

The foetus decided that he had no option but to rely on his own natural wit and guile to foil both his mother and the forces of the After-Life. He began to secrete various items that Martha stole in private little nooks and crannies about her anatomy.

On the last night of his thirty-sixth week, he put his plan into action. In his arsenal: an indelible pen, a potato, a large piece of cotton from the hem of a dress, a thin piece of wire from the supports of a bra, all craftily reassembled. In the dead of night, while Martha was snoring, he gradually worked the zip open from the inside, and did what he had to do.

The following morning, blissfully unaware of the previous night’s activities, Martha went out shopping to Marks and Spencer’s. She picked up some Belgian chocolates and a bottle of port, took hold of her zipper and tried to open her belly. It wouldn’t open. The zipper seemed smaller and more difficult to hold.

‘That bastard,’ she muttered, ‘must be jamming it up from the inside.’ She put down her booty and headed for the exit. On her way out of the shop, she set off the alarms.

‘For Chrissakes!’ she told the detective, ‘I’ve got nothing on me!’ And for once, she meant it.

Back home, Martha attacked her belly with a pair of nail scissors. But the zip wasn’t merely jammed, it was meshing and merging and disappearing, fading like the tail end of a bruise. She was frazzled. She looked around for her cigarettes. She found her packet and opened it. The last couple had gone, and instead, inside, was a note.

Martha, [the note said] I have made good my escape, fully intact. I sewed a pillow into your belly. On the wall of your womb I’ve etched and inked an indelible bar-code. Thanks for the fags.

Love, Baby.

‘But you can’t do that!’ Martha yelled. ‘You don’t have the technology!’ She thought she heard a chuckle, behind her. She span around. On the floor, under the table, she saw a small lump of after-birth, tied up into a neat parcel by an umbilical cord. She could smell a whiff of cigarette smoke. She thought she heard laughter, outside the door, down the hall. She listened intently, but heard nothing more.

The Butcher’s Apprentice (#ulink_613c73b2-8f8d-5b18-984c-6946a7cd5297)

If he had come from a family of butchers maybe his perspective would have been different. He would have been more experienced, hardened, less naive. His mum had wanted him to work for Marks and Spencers or for British Rail. She said, ‘Why do you want to work in all that blood and mess? There’s something almost obscene about butchery.’

His dad was more phlegmatic. ‘It’s not like cutting the Sunday roast, Owen, it’s guts and gore and entrails. Just the same, it’s a real trade, a proper trade.’

Owen had thought it all through. At school one of his teachers had called him ‘deep.’ She had said to his mother on Parents’ Evening, ‘Owen seems deep, but it’s hard to get any sort of real response from him. Maybe it’s just cosmetic.’

His mum had listened to the first statement but had then become preoccupied with a blister on the heel of her right foot. Consequently her grasp of the teacher’s wisdom had been somewhat undermined. When she finally got home that evening, her stomach brimming with sloshy coffee from the school canteen, she had said to Owen, ‘Everyone says that you’re too quiet at school, but your maths teacher thinks that you’re deep. She has modern ideas, that one.’ Owen had appreciated this compliment. It made him try harder at maths that final term before his exams, and leaving. At sixteen he had pass marks in mathematics, home economics and the whole world before him.

In the Careers Office his advisor had given him a leaflet about prospective employment opportunities to fill out. He ticked various boxes. He ticked a yes for ‘Do you like working with your hands?’ He ticked a yes for ‘Do you like working with animals?’ He ticked a yes for ‘Do you like using your imagination?’

When his careers guidance officer had analysed his preferences she declared that his options were quite limited. He seemed such a quiet boy to her, rather dour. She said, ‘Maybe you could be a postman. Postmen see a lot of animals during their rounds and use their hands to deliver letters.’ Owen appeared unimpressed. He stared down at his hands as though they had suddenly become a cause for embarrassment. So she continued, ‘Maybe you could think about working with food. How about training to be a chef or a butcher? Butchers work with animals. You have to use your imagination to make the right cut into a carcass.’ Because he had been in the careers office for well over half an hour, Owen began to feel obliged to make some sort of positive response. A contribution. So he looked up at her and said, ‘Yeah, I suppose I could give it a try.’ He didn’t want to appear stroppy or ungrateful. She smiled at him and gave him an address. The address was for J. Reilly and Sons, Quality Butchers, 103 Oldham Road.

Later that afternoon he phoned J. Reilly’s and spoke to someone called Ralph. Ralph explained how he had bought the business two years before, but that he hadn’t bothered changing the name. Owen said, ‘Well, if it doesn’t bother you then it doesn’t bother me.’

Ralph asked him a few questions about school and then enquired whether he had worked with meat before. Owen said that he hadn’t but that he really liked the sweet smell of a butcher’s shop and the scuffling sawdust on the floor, the false plastic parsley in the window displays and the bright, blue-tinged strip-lights. He said, ‘I think that I could be very happy in a butcher’s as a working environment.’

He remembered how as a child he had so much enjoyed seeing the arrays of different coloured rabbits hung up by their ankles in butcher shop windows, and the bright and golden-speckled pheasants. Ralph offered him a month’s probationary employment with a view to a full-time apprenticeship. Owen accepted readily.

His mum remained uncertain. Over dinner that night she said, ‘It’ll be nice to get cheap meat and good cuts from your new job, Owen, though I still don’t like the idea of a butcher in the family. I’ve nothing against them in principle, but it’s different when it’s so close to home.’

Owen thought carefully for a moment, then put aside his knife and fork and said, ‘I suppose so, but that’s only on the surface. I’m sure that there’s a lot of bloodletting and gore involved in most occupations. I like the idea of being honest and straightforward about things. A butcher is a butcher. There’s no falseness or pretence.’

His dad nodded his approval and then said, ‘Eat up now, don’t let your dinner get cold.’

Owen arrived at the shop at seven sharp the following morning. The window displays were whitely clean and empty. Above the windows the J. Reilly and Sons sign was painted in red with white lettering. The graphics were surprisingly clear and ornate. On the door was hung a sign which said ‘closed’. He knocked anyway. A man with arms like thin twigs opened the door. He looked tiny and consumptive with shrewd grey eyes and rusty hair. Owen noticed his hands, which were reddened with the cold, calloused and porkish. The man nodded briskly, introduced himself as Ralph then took Owen through to the back of the shop and introduced him to his work-mate, Marty. Marty was older than Ralph—about fifty or so—with silvery hair and yellow skin. He smiled at Owen kindly and offered him a clean apron and a bag of sawdust. Owen took the apron and placed it over his head. Ralph helped him to tie at the back. Both Marty and Ralph wore overalls slightly more masculine in design. Owen took the bag of sawdust and said, ‘Is this a woman’s apron, or is it what the apprentice always wears?’

As Ralph walked back into the main part of the shop he answered, ‘It belongs to our Saturday girl, so don’t get it too messy. We’ll buy you a proper overall at the end of the week when we’re sure that you’re right for the job.’

As he finished speaking a large van drew up outside the shop. Ralph moved to the door, pulled it wide and stuck a chip of wood under it to keep it open. He turned to Owen and by way of explanation pointed and said, ‘Delivery. The meat’s brought twice a week. Scatter the sawdust, but not too thick.’

Owen put his hand into the bag of dust and drew out a full, dry, scratchy handful which he scattered like a benevolent farmer throwing corn to his geese. The delivery man humped in half of an enormous sow. She had a single greenish eye and a severed snout. He took it to the back of the shop through a door and into what Owen presumed to be the refrigerated store-room. Before he had returned Ralph had come in clutching a large armful of plucked chickens. As Owen moved out of his way he nodded towards the van and said, ‘I tell you what, why not go and grab some stuff yourself but don’t overestimate your strength and try not to drop anything.’

Owen balanced his packet of shavings against the bottom of the counter and walked out to the van. Inside were a multitude of skins, feathers, meats and flesh. He grabbed four white rabbits and a large piece of what he presumed to be pork, but later found out was lamb. The meat was fresh and raw to the touch. Raw and soft like risen dough. He lifted his selections out of the van and carried them into the shop, careful of the condition of his apron, and repeated this process back and forth for the next fifteen or so minutes. While everyone else moved the meat, Marty busied himself with cutting steaks from a large chunk of beef. When finally all of the meat had been moved Ralph went and had a cigarette outside with the delivery man and Owen picked up his bag of shavings and finished scattering them over the shop floor. On completing this he called over to Marty, ‘Do I have to spread this on the other side of the counter as well?’

Marty smiled at him. ‘I think that’s the idea. It should only take you a minute, so when you’ve finished come over here and see what I’m doing. You never know, you might even learn something.’

Owen quickly tipped out the rest of his bag over the floor at the back of the counter and scuffed the dust around with his foot. It covered the front of his trainer like a light, newgrown beard. Then he walked over to Marty and stood at his shoulder watching him complete his various insertions into the beef. Marty made his final cut and then half turned and showed Owen the blade he was using. He moved the tip of the blade adjacent to the tip of Owen’s nose. ‘A blade has to be sharp. That’s the first rule of butchery. Rule two, your hands must be clean.’ He moved the knife from side to side and Owen’s eyes followed its sharp edge. It was so close to his face that he could see his hot breath steaming up and evaporating on its steely surface. Marty said thickly, ‘This blade could slice your nose in half in the time it takes you to sneeze. Aaah-tish-yooouh!’

Then he whipped the knife away and placed it carefully on the cutting surface next to a small pool of congealing blood. He said, ‘Rule three, treat your tools with respect.’

Owen cleared his throat self-consciously. ‘Will I be allowed to cut up some meat myself today, or will I just be helping out around the shop?’ Marty frowned. ‘It takes a long time and a lot of skill to be able to prepare meat properly. You’ll have to learn everything from scratch. That’s what it means to be the new boy, the apprentice.’

Ralph came back into the shop and set Owen to work cleaning the insides of the windows and underneath the display trays. Old blood turned the water brown. Soon the first customers of the day started to straggle into the shop and he learned the art of pricing and weighing. The day moved on. At twelve he had half-an-hour for lunch.

After two o’clock the shop quietened down again and Owen was sent into the store-room to acquaint himself with the lay-out, refrigeration techniques and temperatures. As he looked around and smelt the heavy, heady smell of ripe meat, he overheard Ralph and Marty laughing at something in the shop. Ralph was saying, ‘Leave him be. You’re wicked Mart.’ Marty replied, ‘He won’t mind. Go on, it’ll be a laugh.’

A few seconds later Ralph called through to him. Owen walked into the shop from the cool darkness of the store-room. The light made his eyes squint. The shop was empty apart from Ralph and Marty who were standing together in front of the large cutting board as though hiding something. Ralph said, ‘Have you ever seen flesh, dead flesh, return to life, Owen?’ Owen shook his head. Marty smiled at him. ‘Some meat is possessed, you know. If a live animal is used as part of a satanic ritual at any point during its life, when it dies its flesh lives on to do the devil’s work. After all, the devil’s work is never done.’

As he finished speaking he stepped sideways to reveal a large chunk of fleshy meat on the chopping board. It was about the size of a cabbage. Everyone stared at it. They were all silent. Slowly, gradually, almost imperceptibly, the meat shuddered. Owen blinked to make sure that his eyes were clear and not deceiving him. After a couple of seconds it shuddered again, but this time more noticeably. It shivered as though it were too cold, and then slowly, painfully, began to crawl across the table. It moved like a heart that pumped under great duress, a struggling, battling, palpitating heart.

Owen’s face blanched. His throat tightened. Ralph and Marty watched his initial reactions and then returned their gazes to the flesh. By now it had moved approximately five or six inches across the cutting board. Its motions were those of a creature in agony, repulsive and yet full of an agonizing pathos. Owen felt his eyes fill, he felt like howling.

Ralph turned back to look at Owen and saw, with concern, the intensity of his reactions. He said, ‘Don’t get all upset, it’s only a joke. It’s got nothing to do with the devil, honest.’

He smiled. Owen frowned and swallowed hard before attempting to reply. ‘Why is it moving? What have you done to it?’

Marty reached towards the piece of convulsing flesh with his big butcher’s hand and picked it up. As he lifted it the flesh seemed to cling to the table. It made a noise like wet clay being ripped into two pieces, like a limpet being pulled from its rock. He turned it over. Underneath, inside, permeating the piece of meat, was a huge round cancer the size of Marty’s fist. A miracle tumour, complete, alive. The tumour was contracting and then relaxing, contracting and relaxing. Maybe it was dying. Owen stared at the tumour in open-mouthed amazement, at its orangy, yellowy completeness, its outside and its core. Marty said, ‘Sometimes the abattoir send us a carcass that shouldn’t really be for human consumption. They know that an animal is ill but they slaughter it just before it dies. They have to make a living too, I suppose.’

With that he threw the meat and its cancerous centre into a large half-full refuse bag and began to wipe over the work surface as though nothing had happened. Owen could still make out the movements of the cancer from inside the bag. A customer came into the shop and Ralph walked over to serve her. Owen felt overwhelmed by a great sense of injustice, a feeling of enormous intensity, unlike anything he had ever experienced before. He felt as though his insides were tearing. He felt appalled. Then instinctively he grabbed at the back of his apron and yanked open its bow. He pulled it over his head and slammed it on to the counter. He said, ‘I’m going home now. I’m going home and I’m taking this with me.’

Before anyone could respond Owen had grabbed the heavy refuse bag full of bones and gristle and off-cuts and had struggled his way out of the shop. When he had gone, Ralph turned to Marty and said, ‘He was a nice enough kid.’

Marty shrugged.

Owen got out of the shop and walked a short distance down the road before placing the bag on the pavement and opening it. He reached inside and felt for the cancer. When he finally touched it, it sucked on his finger like a fish or a baby. He took it out of the bag, pulled off his sweater and bundled the cancer up inside it. He carried it on the bus as though it were a sick puppy. It moved very slightly. When he got home he crept upstairs and locked himself in his room. He closed the curtains and then sat on his bed and unbundled the tumour. He placed it gently on his bedside table under the warm glow of his lamp. It was growing weaker and now moved only slowly.

Owen wondered what he could do for it. He debated whether to pour water on it or whether to try and keep it warm. He wondered whether it might be kinder to kill it quickly, but he couldn’t work out how. He wondered if you could drown a tumour (that would be painless enough), or whether you could chop it in half. But he couldn’t be sure that tumours weren’t like the amoebas that he’d studied in biology at school that could divide and yet still survive. He couldn’t really face destroying it. Instead he decided to simply stay with it and to offer it moral support. He whispered quietly, ‘Come on, it’ll be all right. It’ll soon be over.’

After a few hours the tumour was only moving intermittently. Its movements had grown sluggish and irregular. Owen stayed with it. He kept it company. He chatted. Eventually the tumour stopped moving altogether. Its meaty exterior was completely still. He knew that it was dead. He picked it up tenderly and cradled it in his arms as he carried it downstairs, out of the house and into the garden. Placing it gently on the grass, he dragged at the soft soil in the flower-beds with both his hands until he had dug a hole of significant proportions. Then he placed the still tumour into the hole and covered it over. In a matter of minutes the soil was perfectly compacted and the flowerbed looked as normal.

He went inside and lay on his bed awhile. At six he went downstairs to the kitchen where his mother was beginning to prepare dinner. As he poured himself a glass of water she said, ‘I didn’t know that you were home. How did your first day go?’

Owen gulped down the water and then placed his glass upside down on the draining board. He said, ‘I think I’m going to be a postman.’

Then he dried his hands on a kitchen towel and asked what was for dinner.

G-String (#ulink_5e718e40-8408-5b20-bf3c-468232d19034)

Ever fallen out with somebody simply because they agreed with you? Well, this is exactly what happened to Gillian and her pudgy but reliable long-term date, Mr Kip.

They lived separately in Canvey Island. Mr Kip ran a small but flourishing insurance business there. Gillian worked for a car-hire firm in Grays Thurrock. She commuted daily.

Mr Kip—he liked to be called that, an affectation, if you will—was an ardent admirer of the great actress Katharine Hepburn. She was skinny and she was elegant and she was sparky and she was intelligent. Everything a girl should be. She was old now, too, Gillian couldn’t help thinking, but naturally she didn’t want to appear a spoilsport so she kept her lips sealed.

Gillian was thirty-four, a nervous size sixteen, had no cheek-bones to speak of and hair which she tried to perm. God knows she tried. She was the goddess of frizz. She frizzed but she did not fizz. She was not fizzy like Katharine. At least, that’s what Mr Kip told her.

Bloody typical, isn’t it? When a man chooses to date a woman, long term, who resembles his purported heroine in no way whatsoever? Is it safe? Is it cruel? Is it downright simple-minded?

Gillian did her weekly shopping in Southend. They had everything you needed there. Of course there was the odd exception: fishing tackle, seaside mementos, insurance, underwear. These items she never failed to purchase in Canvey Island itself, just to support local industry.

A big night out was on the cards. Mr Kip kept telling her how big it would be. A local Rotary Club do, and Gillian was to be Mr Kip’s special partner, he was to escort her, in style. He was even taking the cloth off his beloved old Aston Martin for the night to drive them there and back. And he’d never deigned to do that before. Previously he’d only ever taken her places in his H-reg Citroën BX.

Mr Kip told Gillian that she was to buy a new frock for this special occasion. Something, he imagined, like that glorious dress Katharine Hepburn wore during the bar scene in her triumph, Bringing Up Baby.

Dutifully, Gillian bought an expensive dress in white chiffon which didn’t at all suit her. Jeanie—twenty-one with doe eyes, sunbed-brown and weighing in at ninety pounds—told Gillian that the dress made her look like an egg-box. All lumpy-humpy. It was her underwear, Jeanie informed her—If only! Gillian thought—apparently it was much too visible under the dress’s thin fabric. Jeanie and Gillian were conferring in The Lace Bouquet, the lingerie shop on Canvey High Street where Jeanie worked.

‘I tell you what,’ Jeanie offered, ‘all in one lace bodysuit, right? Stretchy stuff. No bra. No knickers. It’ll hold you in an’ everything.’ Jeanie held up the prospective item. Bodysuits, Gillian just knew, would not be Mr Kip’s idea of sophisticated. She shook her head. She looked down at her breasts. ‘I think I’ll need proper support,’ she said, grimacing.

Jeanie screwed up her eyes and chewed at the tip of her thumb. ‘Bra and pants, huh?’

‘I think so.’

Although keen not to incur Jeanie’s wrath, Gillian picked out the kind of bra she always wore, in bright, new white, and a pair of matching briefs.

Jeanie ignored the bra. It was functional. Fair enough. But the briefs she held aloft and proclaimed, ‘Passion killers.’

‘They’re tangas,’ Gillian said, defensively, proud of knowing the modem technical term for the cut-away pant. ‘They’re brief briefs.’

Jeanie snorted. ‘No one wears these things any more, Gillian. There’s enough material here to launch a sailboat.’

Jeanie picked up something that resembled an obscenely elongated garter and proffered it to Gillian. Gillian took hold of the scrap.

‘What’s this?’

‘G-string.’

‘My God, girls wear these in Dave Lee Roth videos.’

‘Who’s that?’ Jeanie asked, sucking in her cheeks, insouciant.

‘They aren’t practical,’ Gillian said.

Jeanie’s eyes narrowed. ‘These are truly modern knickers,’ she said. ‘These are what everyone wears now. And I’ll tell you for why. No visible pantie line!’

Gillian didn’t dare inform her that material was the whole point of a pantie. Wasn’t it?

Oh hell, Gillian thought, shifting on Mr Kip’s Aston Martin’s leather seats, ‘maybe I should’ve worn it in for a few days first.’ It felt like her G-string was making headway from between her buttocks up into her throat. She felt like a leg of lamb, trussed up with cheese wire. Now she knew how a horse felt when offered a new bit and bridle for the first time.

‘Wearing hairspray?’ Mr Kip asked, out of the blue.

‘What?’

‘If you are,’ he said, ever careful, ‘then don’t lean your head back on to the seat. It’s real leather and you may leave a stain.’

Gillian bit her lip and stopped wriggling.

‘Hope it doesn’t rain,’ Mr Kip added, keeping his hand on the gearstick in a very male way, ‘the wipers aren’t quite one hundred per cent.’

Oh, the G-string was a modern thing, but it looked so horrid! Gillian wanted to be a modern girl but when she espied her rear-end engulfing the slither of string like a piece of dental floss entering the gap between two great white molars, her heart sank down into her strappy sandals. It tormented her. Like the pain of an old bunion, it quite took off her social edge.

When Mr Kip didn’t remark favourably on her new dress; when, in fact, he drew a comparison between Gillian and the cone-shaped upstanding white napkins on the fancily made-up Rotary tables, she almost didn’t try to smile. He drank claret. He smoked a cigar and tipped ash on her. He didn’t introduce her to any of his Rotary friends. Normally, Gillian might have grimaced on through. But tonight she was a modem girl in torment and this kind of behaviour quite simply would not do.

Of course she didn’t actually say anything. Mr Kip finally noticed Gillian’s distress during liqueurs.

‘What’s got into you?’

‘Headache,’ Gillian grumbled, fighting to keep her hands on her lap.

Two hours later, Mr Kip deigned to drive them home. It was raining. Gillian fastened her seatbelt. Mr Kip switched on the windscreen wipers. They drove in silence. Then all of a sudden, wheeeu-woing! One of the wipers flew off the windscreen and into a ditch. Mr Kip stopped the car. He reversed. He clambered out to look for the wiper, but because he wore glasses, drops of rain impaired his vision.

It was a quiet road. What the hell. Mr Kip told Gillian to get out and look for it.

‘In my white dress?’ Gillian asked, quite taken aback.

Fifteen minutes later, damp, mussed, muddy, Gillian finally located the wiper. Mr Kip fixed it back on, but when he turned the relevant switch on the dash, neither of the wipers moved. He cursed like crazy.

‘Well, that’s that,’ he said, and glared at Gillian like it was her fault completely. They sat and sat. It kept right on raining.

Finally Gillian couldn’t stand it a minute longer. ‘Give me your tie,’ she ordered. Mr Kip grumbled but did as she’d asked. Gillian clambered out of the car and attached the tie to one of the wipers.

‘OK,’ she said, trailing the rest of the tie in through Mr Kip’s window. ‘Now we need something else. Are you wearing a belt?’

Mr Kip shook his head.

‘Something long and thin,’ Gillian said, ‘like a rope.’

Mr Kip couldn’t think of anything.

‘Shut your eyes,’ Gillian said. Mr Kip shut his eyes, but after a moment, naturally, he peeped.

And what a sight! Gillian laboriously freeing herself from some panties which looked as bare and sparse and confoundedly stringy as a pirate’s eye patch.

‘Good gracious!’ Mr Kip exclaimed. ‘You could at least have worn some French knickers or cami-knickers or something proper. Those are preposterous!’

Gillian turned on him. ‘I’ve really had it with you, Colin,’ she snarled, ‘with your silly, affected, old-fashioned car and clothes and everything.’

From her bag Gillian drew out her Swiss Army Knife and applied it with gusto to the plentiful elastic on her G-string. Then she tied one end to the second wiper and pulled the rest around and through her window. ‘Right,’ she said, ‘start up the engine.’

Colin Kip did as he was told. Gillian manipulated the wipers manually; left, right, left, right. All superior and rhythmical and practical and dour-faced.

Mr Kip was very impressed. He couldn’t help himself. After several minutes of driving in silence he took his hand off the gearstick and slid it on to Gillian’s lap.

‘Watch it,’ Gillian said harshly. ‘Don’t you dare provoke me, Colin. I haven’t put my Swiss Army Knife away yet.’

She felt the pressure of his hand leave her thigh. She was knickerless. She was victorious. She was a truly modern female.

The Three Button Trick (#ulink_7445a7ff-9b47-5d49-b3d9-8ec627f828a8)

Jack had won Carrie’s heart with that old three button trick.

At the genesis of every winter, Jack would bring out his sturdy but ancient grey duffel coat and massage the toggles gently with the tips of his fingers. He’d pick off any fluff or threads from its rough fabric, brush it down vigorously with the flat of his hand and then gradually ease his way into it. One arm, two arms, shift it on to his shoulders, balance it right—the tips of the sleeves both perfectly level with each wrist—then straighten the collar.

Finally, the toggles. The most important part. He’d do them one-handed, pretending, even to himself, some kind of casualness, a studied—if fallacious—preoccupation, his eyes unfocused, imagining, for example, how it felt when he was a small boy learning to tell the time. His father had shown him: ten past, quarter past, see the little hand? See the big hand? But he hadn’t learned. It simply didn’t click.

So Jack’s mother took over instead. She had her own special approach. The way she saw it, any child would learn anything if they thought there was something in it for them: a kiss or a toy or a cookie.

Jack’s mother baked Jack a Clock Cake. Each five-minute interval on the cake’s perimeter was marked with a tangy, candied, lemon segment. The first slice was taken from the midday or midnight point at the very top of the cake and extended to the first lemon segment on the right, which, Jack learned, signified five minutes past the hour. ‘If the little hand is on the twelve,’ his mother told him, ‘then your slice takes the big hand to five minutes past twelve.’

Jack wrinkled up his nose. ‘How about if I have a ten past twelve slice?’ he suggested.

He got what he’d asked for.

Jack was born in Wisconsin but moved to London in his early twenties and got a job as a theatrical producer. He’d already worked extensively off-off Broadway. He met Carrie waiting for a bus on a Sunday afternoon outside the National Portrait Gallery. It was the winter of 1972. He was wearing his duffel coat.

Carrie was a blonde who wore her hair in big curls, had milk-pudding skin and breasts like a roomy verandah on the front of her body’s smart Georgian townhouse frame. Close up she smelled like a bowl of Multi-flavoured Cheerios.

Before Jack had even smelled her, though, he smiled at her. She smiled in return, glanced away—as girls are wont to do—and then glanced back again. Just as he’d hoped, her eyes finally settled on the toggles on his coat. She pointed. She grinned. ‘Your buttons …’

‘Huh?’

‘The buttons on your coat. You’ve done them up all wrong.’

He looked down and pretended surprise. ‘I have?’

Jack held his hands aloft, limply, gave her a watery smile but made no attempt to righten them. Carrie, in turn, put her hand to her curls. She imagined that Jack must be enormously clever to be so vague. Maybe a scientist or a schoolteacher at a boys’ private school or maybe a philosophy graduate. Not for a moment did it dawn on her that he might be a fool. And that was sensible, because he was no fool.

Carrie met Sydney two decades later, while attending self-defence classes. Sydney had long, auburn ringlets and freckles and glasses. She was Australian. Her father owned a vineyard just outside Brisbane. Sydney was a sub-editor on a bridal magazine. She was strong and bare and shockingly independent. On the back of her elbows, Carrie noticed, the skin was especially thick and in the winter she had to apply Vaseline to this area because otherwise her skin chapped and cracked and became inflamed. The reason, Sydney informed Carrie, that her elbows got so chapped, was that she was very prone to resting her weight on them when she sat at her desk, and also, late at night, when she lay in bed reading or thinking, sometimes for hours.

Sydney was thirty years old and an insomniac. Had been since puberty. As a teenager she’d kept busy during the long night hours memorizing the type-of-grape in the type-of-wine, from-which-vineyard and of-what-vintage. Also she collected wine labels which she stuck into a special jotter.

Nowadays, however, she’d spend her wakeful night-times thinking about broader subjects: men she met, men she fancied, men she’d dated, men she’d two-timed, and if none of these subjects seemed pertinent or topical—during the dry season, as she called it—well, then she’d think about her friends and their lives and how her life connected with theirs and what they both wanted and what they were doing wrong and how and why.

Carrie appreciated Sydney’s attentiveness. If Jack had been working late, if Jack kept mentioning the name of an actress, if Jack told her that her skin looked sallow or her roots were showing, well, then she would tell Sydney about it and Sydney would spend the early hours of every morning, resting on her elbows and mulling it all over.

Sydney had a suspicion that Jack was up to something anti-matrimonial and had hinted as much to Carrie. Hinted, but nothing more. Carrie, however, took only what she wanted from Sydney’s observations and left the rest. In conversational terms, she was a fussy eater.

Jack walked out on Carrie after twenty-one years of marriage, two days before her forty-fourth birthday. The following night, after he’d packed up and gone, she and Sydney skipped their karate class and sat in the leisure centre’s bar instead. Sydney ordered two bottles of Bordeaux. She wasn’t in the least bit perturbed by Carrie’s predicament. In fact, she was almost pleased because she’d anticipated that this would happen a while ago and was secretly gratified by the wholesale accuracy of her prediction.

‘You’re still a babe, Carrie,’ Sydney whispered, pouring her some more wine. ‘You could have any man.’

‘I don’t want any man,’ Carrie whimpered. ‘I only want Jack. Only Jack. Only him.’

‘That guy Alan,’ Sydney noted, ‘who takes the Judo class. I know he likes you. Sometimes it seems like his eyes are stuck to your tits with adhesive.’

‘Please!’

‘It’s true.’

‘Jack only walked out yesterday, Sydney, probably for a girl fifteen years my junior. You really think I care about anything else at the moment?’

Sydney had great legs; long and lithe and small-kneed. Gazelle legs, llama legs. She crossed them.

‘I’m simply observing that Jack isn’t the only shark in the ocean.’

Carrie took a tissue from her sports bag and dusted her cheeks with it.

‘I remember the very first time I ever met Jack, waiting for a bus outside the National Portrait Gallery. A Sunday afternoon. He had his coat buttoned up all wrong and I pointed it out to him and we started talking …’ Carrie stopped speaking and hiccuped.

Sydney chewed her bottom lip. That old three button trick, she was thinking. The slimy bastard.

‘You know, Carrie,’ she said sweetly. ‘You’re still so beautiful. You’re still the biggest lily in the pond. You’re still floating on the surface and bright enough to catch the attention of any insect or amphibian that might just happen to be passing.’ She paused. ‘Even a heron,’ she added, as an afterthought.

Carrie scrabbled in her sports bag. She grabbed her purse, opened it, took out a twenty-pound note to pay the barman for the bottles of wine.

‘My treat,’ Sydney interjected.

Carrie paid him anyway. She was about to shut her purse but then paused and delved inside it.

‘Look,’ she said, her voice trembling, holding aloft a blue card.

Sydney put out her hand. ‘What is it?’

‘Our season ticket to the ballet. We went every week. It was one of those routines …’

‘Well,’ Sydney took the ticket and perused it, ‘you shall go to the ball, Cinders.’

‘What?’

‘You and me. We’ll go together. When is it?’

‘Wednesday.’

Sydney handed the card back. ‘Fine.’

As it turned out, Sydney couldn’t make it. She rang Carrie at the last minute. Carrie answered the phone wrapped up in a towel, pink from a hot bath.

‘What? You can’t make it?’

‘But I want you to go, anyway. Find someone else.’

‘There is no one else. It doesn’t matter, though. I wasn’t really in the mood myself.’

‘Carrie, you’ve got to go. Alone if needs be. It’s the principle of the thing’

‘I know, but it’s just …’

‘What?’

‘It’s kind of like a regular box and we share it with some other people and if I go alone …’

‘So? That’s great. It means you won’t feel entirely isolated, which is ideal.’

‘And then there’s this fat old man called Heinz who’s always there. A complete bore. We really hate him.’

‘Heinz?’

‘Yes. Jack always found him such a pain. We even tried to get a transfer …’

‘Bollocks. Just go. Ignore him. What’s the ballet?’

‘Petrushka.’

‘Yip!’

‘I’ve seen it before. It’s not one of my particular favourites.’

‘Go anyway. You’ve got to start forging your own path, Carrie. You’ll thank me after. Honestly.’

She’d made a special effort, with her hair and her make-up. She was wearing a dress that she’d bought for the previous Christmas. It was a glittery burgundy colour. Her lips matched. The box was empty when she arrived. She felt stupid. She sat down.

After five minutes, a couple she knew only to say hello to arrived and took their seats. They smiled and nodded at Carrie. She did the same in return. She then paged through her programme and pretended that she wasn’t overhearing their conversation about the kind of conservatory they should build on to the back of their house. He wanted a big one that could fit a table to seat at least six. She wanted a small, bright retreat full of orchids and tomato plants.

Carrie kept reading and rereading the names of the principal dancers. The orchestra’s preparatory honking and parping jangled in her throat and with her nerves. She closed her eyes. I will count to ten. One, two, three, four …

‘Ooof! Here we go, here we go!’

Heinz, squeezing his way over to his seat, pushing his considerable bulk between the two rows of chairs.

‘Oi! Hup! There we are.’

Carrie opened her eyes and stared at him. He had a box of chocolate brazils in one hand and a bulging Selfridges bag in the other, which he almost, but couldn’t quite, fit into the gap between his knees and the front of the box.

Carrie’s gut rumbled her antipathy. He smelled, always—as Jack had noted on many an occasion—of wine gums and Deep Heat. An old smell. He must have been in his eighties, wore a grey-brown toupee and weighed in, she guessed, like a prize bull, at around three hundred and twenty pounds.

Carrie converted this weight into stone and then back again to occupy herself.

Heinz nodded at her. She nodded back. He always wore a sludge-coloured bow tie. It hung like a shiny little brown turd, poised under his chin.

Heinz endeavoured, with a great harrumphing, to find adequate room by his knees for his bag. ‘Uh-oh! Uh-oh!’

Carrie gritted her teeth.

‘If you haven’t room for your shopping, this chair is empty.’ She indicated Jack’s empty seat which separated them.

‘Empty? Really? That lovely man of yours isn’t with you tonight? Empty, you say?’ He wheezed as he spoke, like an asthmatic Persian feline, which made his German accent even more pronounced.

You’d think, Carrie speculated, that a wheeze would take the hard edges off a German accent, but you’d be wrong to think so.

‘Would you mind’—close to her ear—’if I sat next to you and put my bag on the other seat?’

My God! Carrie thought, fixing her eyes on the stage curtains and breathing a sigh of relief at their preliminary twitchings.

‘Brazil?’

Ten minutes in, Heinz was whispering to her.

‘What?’

‘Brazil? Go on. Have one.’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Go on!’

‘No. I don’t actually like brazils. Nuts give me hives.’

Heinz closed the box and rested it on his lap.

During the intermission, Heinz regaled Carrie with tales about the relative exclusivity of the Turner and Booker prizes. He liked the opera, it turned out, especially Mozart. He found camomile tea to be excellent for sleeplessness. He was a widower of seven years.

Carrie noticed how the box’s other regulars smiled at her sympathetically whenever they caught her eye. It was odd, really, because actually, with increased acquaintance, Heinz wasn’t all that bad. In fact, if anything, he’d made her the centre of attention in the box. The focus, the axis. She felt rather like Princess Margaret opening a day care centre in Fulham.

As the safety curtain rose for the second half, Heinz was telling Carrie how he’d just been to Selfridges to buy a cappuccino maker. He loved everything Italian. He’d been stationed there during the war.

As the stage curtains closed, Heinz mopped something from the corner of his eye and muttered gutturally, ‘Poor, poor old Petrushka!’

During the curtain calls Heinz told Carrie that he often felt that it was sadder to be a sad puppet than a sad person.

‘Pardon?’

‘Petrushka, the puppet. Sometimes it feels like the ballet is sadder because he is a puppet and not a living being.’

‘Oh, right. Yes.’ Carrie finished applauding and leaned over to pick up her bag. Heinz stayed where he was.

‘How will you be getting home then, Carrie?’

‘I brought my car.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes.’

‘So maybe, maybe you wouldn’t mind joining an old man for a cup of coffee somewhere before you make your way back?’

‘Uh?’ Carrie was agog.

‘Oh! Um …’ She thought about it for a long moment. She imagined her quiet house, her empty bed. ‘OK,’ she said cheerfully, ‘love to.’

Sydney was late for Thursday’s class so they didn’t have a chance to chat beforehand. Afterwards though, in the sauna, they had plenty of opportunity for exchanging news. Carrie wore a white towel around her essentials and sat on the lower bench. Sydney wore nothing and sat on the upper.

‘How’d it go then?’

‘Pardon?’

‘Last night.’

‘Fine.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Yes.’ Carrie cleared her throat. ‘I mean, you know how it is when you do something alone for the first time when you’re accustomed to doing it with someone else …’

‘I guess so.’

Sydney lay down flat on her back. Whenever she lifted her shoulders or her buttocks, they stuck to the wooden boards, aided by the natural glue of her body’s moisture. The noise this made reminded Carrie of the sound of an emery board against a ragged nail.

‘Actually,’ Carrie said, grinning, ‘La Fille Mal Gardée is my favourite ballet.’

‘Really? You like an element of slapstick, huh?’

‘I suppose I must do.’

‘Myself, I prefer a tragedy. I find that tragedy best reflects my emotional and psychological state.’

Carrie turned and stared straight into Heinz’s frogspawn eyes. ‘You’re kidding.’

‘Me? Kidding? Not at all. Not at all.’

Heinz offered Carrie his family-size box of Maltesers.

‘Thanks.’

Carrie took one and popped it into her mouth. ‘That’s the strangest part …’ she said, chewing and enjoying the sensation of chocolate and malt on her tongue. ‘I’ve been to four ballets with you and never for a moment did I think you seemed like a sad or a dissatisfied person.’

It was the interval. Heinz and Carrie were propping up the theatre bar. Heinz had discovered that Carrie’s favourite winter tipple was port and lemon. He’d taken to ordering her one before the show. This meant they didn’t have to wait to be served during the intermission.

Heinz smiled at Carrie. ‘You see the best in everyone.’

‘Maybe I’m just insensitive.’

‘You? Insensitive? Never. You’re an angel.’

A man standing just to Carrie’s left turned and stared at them. Carrie caught his eye. His expression was a mixture of amusement and confusion. Carrie took a sip of her drink. People were so funny, the way they stared. Their quizzical expressions. It had begun to dawn on her that when she was out with Heinz she became a puzzle. She became mysterious.

Alone, at home, in life, she felt like something dried-up, wrung-out and innocuous. Out with Heinz, she felt like she was transformed into something much less explicable.

Heinz was bossy and opinionated but he wasn’t entirely unobservant. He rolled his eyes at Carrie. ‘Probably thinks you’re my daughter.’

Carrie shrugged. ‘And I could be too, easily.’

Carrie often found Heinz to be genuinely perceptive. At their second ballet together he’d said, And your husband …?’

To which she’d responded, ‘I don’t ever want to talk about him.’

‘Very well.’

And they’d never spoken about him since. It was almost like, Carrie decided, Jack had never even existed.