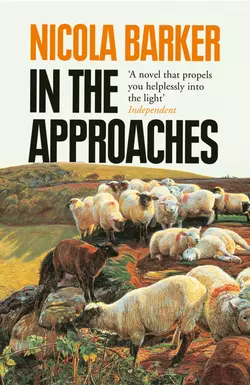

In the Approaches

Nicola Barker

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 996.84 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Nicola Barker’s readers are primed to expect surprises, but her tenth novel delivers mind-meld on a metaphysical scale. From quiet beginnings in the picturesque English seaside enclave of Pett Level, ‘In The Approaches’ ultimately constructs its own anarchic city-state on the previously undiscovered common ground between G.K. Chesterton and Philip K. Dick. On the one hand, this is an old-fashioned romantic comedy of fused buttocks, shrunken heads and Irish-Aboriginal saints; on the other it’s Barker’s wildest and most haunting book since 2007’s Booker Prize-shortlisted ‘Darkmans’.Following previous celebrations of the enduring allure of the posted letter (’Burley Cross Postbox Theft’) and the pre-lapsarian innocence of pre-Twitter celebrity (Booker-longlisted ‘The Yips’), this concluding instalment of Barker’s subliminally affiliated ‘digital trilogy’ imagines a basis for the internet in Catholic theology. Set in a 1984 which seems almost as distantly located in the past as Orwell’s was in the future, ‘In the Approaches’ offers a captivating glimpse of something more shocking than any dystopia – the possibility of faith.