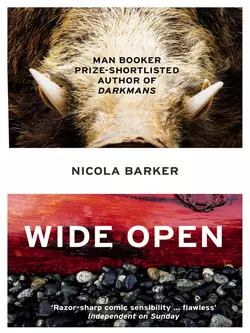

Wide Open

Nicola Barker

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1163.51 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The novel for which Nicola Barker, one of our times most original, funny and anarchic writers, won the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2000.‘Wide Open’ is set on the strange Isle Of Sheppey, which pokes out into into the estuary of the River Thames. On this forgotten misty island there is a nudist beach, a nature reserve, a wild boar farm and not much else. The landscape is bare, but the characters are brimming with life. There′s Luke, who specialises in dot-to-dot pornography, and lippy Lily, just 17 and full of outrageous anger. They are joined by Jim and the 8-year-old, Nathan, as well as the mysterious figure of Ronnie, who though plain has dark, telling eyes.Each one is drifting in turbulent, emotional currents, fighting the rip tide of a past, bleak with secrets and fear. Years later adult Nathan works in a Lost Property department, an irony that is almost brutal in its compassion.A novel about stripping off layers of prejudice and lies, about the possibility of redemption, and laying bare the truth. It is also about coming to terms with the past, and about the fantasies people construct in order to protect their fragile inner selves.