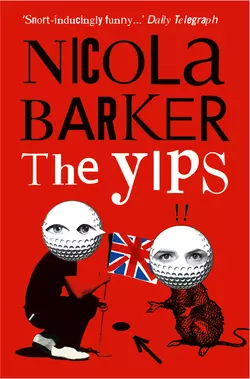

The Yips

Nicola Barker

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ′There was a rat in the bath′, Gene explains. ′It′s a long story, but basically I fished it out and was carrying around by the tail, not quite sure how to dispose of it, when I managed to barge in on this woman having a genital tattoo′.2006 is a foreign country; they do things differently there. Tiger Woods′ reputation is entirely untarnished and the English Defence League does not exist yet. Storm-clouds of a different kind are gathering above the bar of Luton′s less than exclusive Thistle Hotel. Among those caught up in the unfolding drama are a man who′s had cancer seven times, a woman priest with an unruly fringe, the troubled family of a notorious local fascist, an interfering barmaid with three E′s at A-level but a PhD in bullshit, and a free-thinking Muslim sex therapist and his considerably more pious wife. But at the heart of every intrigue and the bottom of every mystery is the repugnantly charismatic figure of Stuart Ransom – a golfer in free-fall.Nicola Barker′s THE YIPS is at once a historical novel of the pre-Twitter moment, the filthiest state-of-the-nation novel since Martin Amis′ MONEY and the most flamboyant piece of comic fiction ever to be set in Luton.