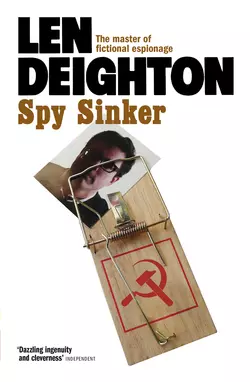

Spy Sinker

Len Deighton

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 866.61 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The long-awaited reissue of the final part of the classic spy trilogy, HOOK, LINE and SINKER, when the Berlin Wall divided not just a city but a world.Bernard Samson is surrounded by puzzles and none more complex than Fiona, his wife and the mother of his children. But as a mystery, she is by no means alone. Can a man love two women at the same time? Can a man serve two masters?Tessa Kosinski, Bernard′s socialite sister-in-law, is not the ′other woman′. She is as faithful to Bernard and Fiona as she is unfaithful to her doting husband. But she is vulnerable, and slowly she is drawn from the bright lights of London to the murkiest and bizarre corners of Berlin.